Edited by: Dr. Sergi Bermúdez i Badia

(University of Madeira, Funchal, , Portugal)

Dr. Alice Chirico

(No Organisation - Home based - 0595549)

Dr. Andrea Gaggioli

(Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Milano,Italy)

Prof. Dr. Ana Lúcia Faria

(University of Madeira, Funchal, Portugal)

Last update: December 2025

More infoThe mental health of young adults, particularly university students, has become a global concern. Nature-based interventions have shown promise in alleviating anxiety and negative emotions. This study explored the effectiveness of Virtual Reality (VR)-based nature therapy in reducing anxiety, negative mood, and stress while enhancing mindfulness among university students. A three-armed randomised controlled trial was conducted. Two hundred thirty-six students with anxiety symptoms were randomly assigned to either a VR intervention group, a placebo control group, or an inactive control group after the baseline assessment. We developed a VR intervention system called Mind Nature, featuring nature-based activities such as planting, observing natural environments, rowing across the water, and personal reflection, all accompanied by mindful audio guidance within a fully immersive 360-degree, three-dimensional VR environment. The placebo control group engaged in a VR sports game using a VR headset, while the control group received no intervention. Each session lasted approximately 30 min. Anxiety, mood, stress, mindfulness, and nature-relatedness were measured three times: pre- and post-intervention and at a 2-week follow-up. Results revealed significant group-time interaction effects, with greater reductions in anxiety, negative affect, and stress in the VR intervention group compared to the placebo and control groups. This study highlights the effectiveness of VR-based nature therapy and its potential as an effective and convenient mental health intervention for university students, offering a promising complement to traditional therapeutic approaches.

The study was registered online at the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ID: ChiCTR2400089445)

Student mental health issues are now recognised as a global public health concern (Sheldon et al., 2021) Anxiety, negative mood and stress are common mental health issues among university students (Duffy et al., 2019; Fan et al., 2024; Hysenbegasi et al., 2005). Anxiety disorders, including generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), are characterised by persistent and excessive worry that can significantly impair daily functioning. These conditions encompass both trait anxiety (a stable predisposition to perceive situations as threatening) and state anxiety (temporary feelings of worry or tension triggered by specific events), often requiring clinical intervention for effective management. Anxiety symptoms refer to subclinical experiences such as restlessness, tension, avoidance, and gastrointestinal discomfort (Szuhany & Simon, 2022; Wang et al., 2023). The prevalence of anxiety symptoms among Chinese university students is 25 % (Tang et al., 2022), higher than Chinese adults in the general population at 9.84 % (Wang et al., 2022; Wang and Liu, 2022). Anxiety symptoms can negatively impact academic functioning, leading to low motivation, low self-efficacy, procrastination, physical discomfort and low overall well-being (Fan et al., 2024; Johansson et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023), creating significant long-term impact on students' mental health, social functioning, and academic performance (Tang et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2023).

Various interventions have been employed to address the increasing mental health challenges university students face, including medication, psychological counselling, cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), and mindfulness-based interventions (Shirotsuki & Sugaya, 2021). However, several limitations hinder these approaches. Firstly, there is a shortage of qualified mental health professionals in China, which restricts students' access to psychological support. Secondly, medications often have side effects, and the cost of therapy is prohibitive for many students, limiting its affordability (Deng et al., 2022). Thirdly, delayed treatment is common, as many students are unaware of the need for help or are reluctant to seek it due to stigma, resulting in lower help-seeking rates despite the high prevalence of mental health issues (Gaddis et al., 2020; Yin et al., 2020). International research highlights that traditional mental health supports often require significant financial costs and time commitments, with long waiting periods frequently reported before access (Shepardson et al., 2023). These challenges show the global need for easily accessible and effective interventions to manage anxiety symptoms and negative moods, aiming to prevent the development of more severe mental disorders (Lau et al., 2024).

Meanwhile, mental health challenges in China are worsened by limited resources, high demand, and stigma, leaving many without adequate care. Digital psychological interventions, which have shown moderate effectiveness in reducing symptoms of depression and substance misuse in low- and middle-income countries (Hedges’ g = 0.60), provide a promising solution where traditional care is unavailable or insufficient (Fu et al., 2020). Tailored digital tools could address China's unmet mental health needs by providing effective, widely available support (Fu et al., 2020).

Nature-based interventions have been increasingly recognised internationally for their potential to aid individuals recovering from stress and anxiety while also enhancing positive mood (Shanahan et al., 2019). These interventions often involve activities such as forest therapy, nature walks, and immersive experiences in green spaces, capitalising on the restorative effects of natural environments (Coventry et al., 2021). Research suggests that exposure to nature can promote psychological well-being by reducing stress hormone levels, improving cognitive functioning, and fostering relaxation. Moreover, nature-based interventions are generally accessible and cost-effective, making them attractive alternatives to conventional mental health treatments. Attention Restoration Theory (ART) and Stress Reduction Theory (SRT) support the potential psycho-physical benefits of nature-based interventions, proposing that intentional attention to the present moment in natural environments can mitigate anxiety symptoms and stress and foster a sense of calm and well-being (Djernis et al., 2019; Kaplan, 2001, 1995; Ulrich et al., 1991). Mindfulness plays a significant mediating role in the relationship between nature connectedness and psychological benefits (Huynh & Torquati, 2019). Macaulay and colleagues (2022) propose an integrated framework of how mindfulness enhances the benefits of nature therapy. They identified three key mechanisms as central to promoting psychological restoration and nature connection: perceptual sensitivity, decentering, and non-reactivity. Perceptual sensitivity increases environmental awareness; decentering detaches individuals from internal thoughts, and non-reactivity aids emotional regulation. Together, these three mechanisms foster deeper engagement with nature, enhancing positive mood and the therapeutic effects of nature exposure (Macaulay et al., 2022). However, the effects of nature-based interventions can be influenced by individual differences in nature-relatedness, meaning not everyone may benefit equally from such interventions (Merino et al., 2020). Additionally, access to green spaces can be limited in urban areas, reducing the feasibility of widespread implementation (Hartig et al., 2014).

Virtual Reality (VR) has been shown to enhance students’ mental health (Freeman et al., 2018) and has the potential to be used to deliver nature-related interventions for university students living in urban areas where access to natural environments might be low. In the past decade, VR has been extensively utilised as a form of accessible psychological intervention (Arpaia et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2023). A recent study has highlighted the potential of VR-enhanced relaxation protocols in reducing anxiety and improving engagement (Pardini et al., 2024). Although VR is often used in the treatment of phobias (Huang et al., 2022; Luo et al., 2022), a systematic review (N = 20) found that VR effectively treats anxiety, depression, PTSD, psychosis, and stress, with 65 % of studies demonstrating VR's efficacy in reducing stress and negative emotions, though 35 % showed limited effects on enhancing positive mood (Li Pira et al., 2023).

Immersion in natural environments, whether experienced directly or through virtual reality (VR), significantly reduces stress and enhances mood (Browning et al., 2023; Berto, 2014; Cieślik et al., 2020; Reynolds et al., 2020). VR's immersive qualities deepen engagement with virtual natural settings, while mindfulness techniques help individuals focus on and appreciate sensory details, promoting mental clarity and emotional balance (Djernis et al., 2019; Kaplan, 2001). Virtual nature therapy leverages these principles, delivering controlled and immersive experiences replicating natural environments to provide similar therapeutic effects (Lattie et al., 2022). For example, exposure to a VR coral reef reduced negative affect and boredom while increasing positive affect and nature connectedness, outperforming traditional 2D videos (Yeo et al., 2020).

VR-based nature therapy can reduce anxiety symptoms and stress (Cieślik et al., 2020; Fodor et al., 2018; Reynolds et al., 2020), however, the specific nature scenes used, their integration with mindfulness practices, and their role in mood and anxiety reduction are rarely explored. There is a need for an in-depth study with a robust research design to investigate the psychological effects of VR-based nature therapy and to gain a more nuanced understanding of the underlying mechanisms involved (Liu et al., 2023). Specifically, how the combination of VR technology with nature therapy influences mood changes and anxiety levels of university students remain to be fully explored. To achieve an immersive and comprehensive nature therapy experience using 3D virtual reality, a novel one-off VR-based nature therapy session, named Mind Nature, has been developed by the clinical psychology lab at the University (names of lab and university anonymised for peer review purposes). Mind Nature integrates mindfulness audio guidance with virtual nature exploration and interactive activities to offer a reflective and calming experience. The current study also seeks to determine whether the effects of Mind Nature can last for two weeks, which is a common time frame for assessing changes in anxiety symptoms. The study uses a randomised control trial design to examine the effectiveness of VR-based nature therapy integrated with mindfulness in improving positive mood while reducing anxiety and negative mood among university students. A secondary goal is to examine the effect of the intervention on the improvement of mindfulness, nature-relatedness levels, and mental well-being. The detailed research hypotheses are:

- i)

A VR-based nature intervention (Mind Nature) will significantly reduce university participants' anxiety symptoms, state-trait anxiety, negative affect, and stress while improving their positive affect, mindfulness, and nature-relatedness.

- ii)

Participants in the VR intervention group will demonstrate significantly greater levels of reduction in anxiety symptoms, state-trait anxiety, negative mood, and stress while improving greater levels of positive affect, mindfulness, and nature-relatedness compared to students in the placebo and control groups.

- iii)

The positive effects of the intervention will last two weeks.

The study employed a single-blind Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) design and was conducted between April and September 2024, in which participants were blinded to condition allocation, whereas researchers were necessarily aware of group assignments due to methodological constraints. To maintain scientific integrity and allow for meaningful comparisons, the study specifically used a three-arm randomised controlled design. Participants were randomly allocated to one of three groups: (1) a VR-based nature therapy group (VR group), (2) an active control group that included VR gaming (Placebo group), or (3) an inactive control group that received no intervention. The active control condition was purposefully constructed to mirror the VR nature therapy condition's format, length, and VR immersion—including certain play activities with natural visual elements —while excluding any organised therapeutic material. This enabled us to discriminate between the effects of the guided nature-based intervention and those caused by general VR involvement or passive exposure to nature-related stimuli. The inactive control group served as a baseline for observing normal psychological variations over time and analysing intervention effects (Tock et al., 2022; Michopoulos et al., 2021Karlsson & Bergmark, 2015).

The study was registered online at the Clinical Trial Registry (ID: ChiCTR2400089445). Inclusion criteria were: 1) aged between 18 and 30 years; 2) full-time university students; 3) with mild to moderate anxiety in two weeks. Potential participants were excluded if they: 1) have severe reading, hearing, or visual impairments; 2) have been diagnosed with serious mental disorders in 6 months, including schizophrenia and dissociative disorder; 3) were on medication related to mental illness or sleep disorders. The research flyer was advertised through the university community, the library notice board, and the official website of the research lab. Participants scanned the QR code on the flyer and were invited to complete the screening test and provide their email addresses. After the screening, eligible participants were contacted via email by one of the researchers and were randomly assigned to one of three groups using the R Studio randomisation programme.

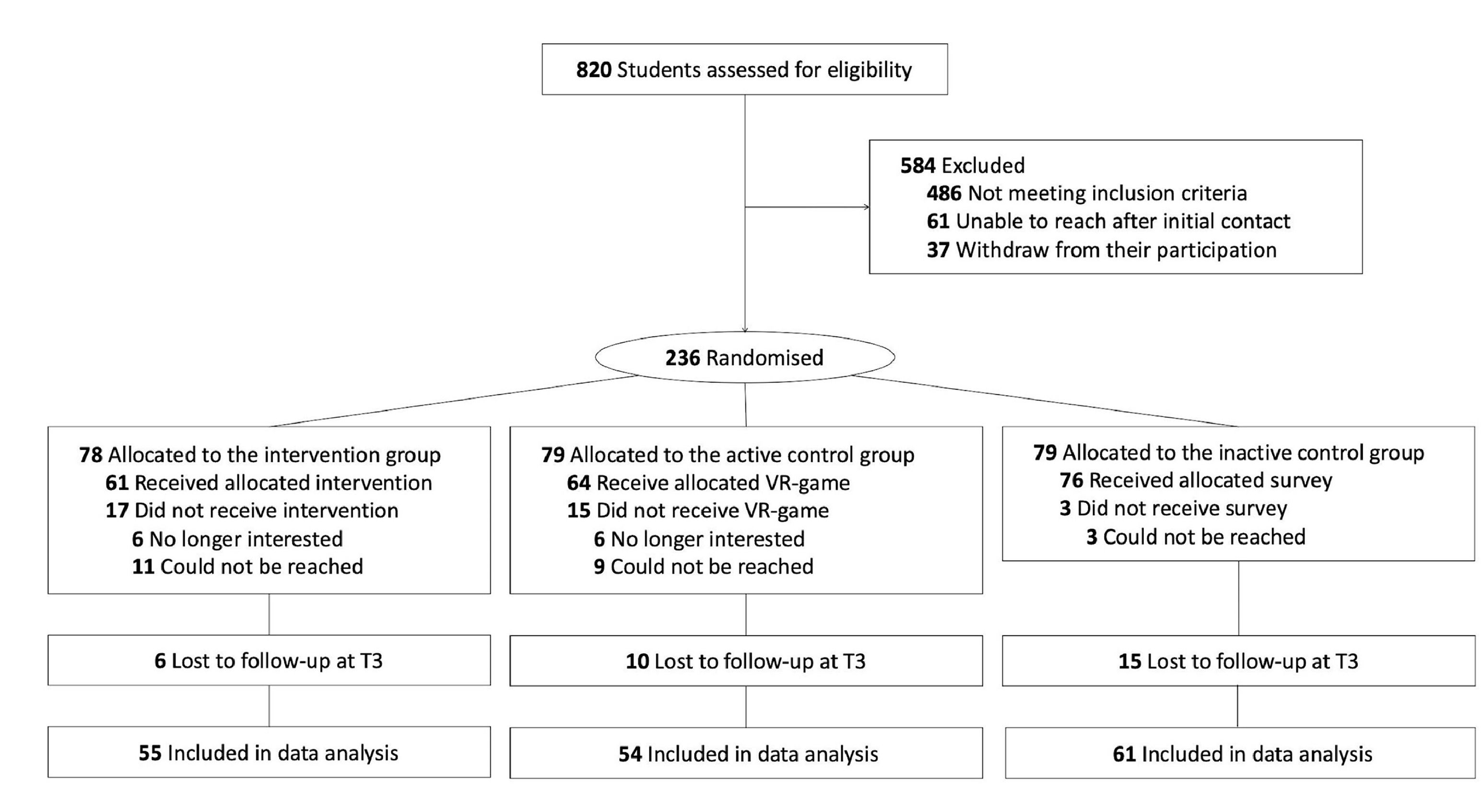

A priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., 2007) to determine the minimum sample size required for a 3 (group: experimental group, active control, inactive control) × 3 (time: pre-test, post-test, follow-up) mixed-design repeated-measures ANOVA. Assuming a medium effect size (f = 0.25), an alpha level of 0.05, a desired statistical power of 0.80, and a nonsphericity correction (ε) of 0.75, the analysis indicated that a total sample size of 157 participants would be required to detect a significant group × time interaction effect. To account for an anticipated 30 % attrition rate, consistent with previous psychological intervention studies (Iliakis et al., 2021), we aimed to recruit at least 225 participants (around 75 per group). There were 820 college students assessed for eligibility; 486 did not meet the criteria, 61 could not be contacted, and 37 withdrew. Overall, 236 participants were included in the study. During the follow-up, 31 participants dropped out, leaving 170 participants for the final analysis: 55 in the VR nature intervention group, 54 in the placebo VR game group, and 61 in the control group (see more details in Fig. 1).

MeasurementsDemographics and screening testDemographic Information. participants were asked to complete an information sheet with personal information including name, age, gender, educational level, place of residence, and mental medical history.

To ensure comprehensive screening for mild to moderate anxiety, we employed both the Short Version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). While BAI provides a broader assessment of anxiety symptoms, GAD-7 focuses specifically on generalised anxiety disorder. The combined use of both scales allows for a more nuanced identification of anxiety levels across a wider spectrum of anxiety-related experiences, improving the accuracy of participant screening. Participants scoring 8 or higher on the BAI (indicating mild anxiety) and 5 or higher on the GAD-7 (indicating mild generalized anxiety) were included in the study.

The Chinese version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) was used to assess the anxiety levels of participants (Pang et al., 2019). State anxiety items consist of statements such as: “I am tense; I am worried” and “I feel calm; I feel secure.” For trait anxiety, items include: “I worry too much over something that really doesn’t matter” and “I am content; I am a steady person.” Respondents evaluate these statements on a 4-point scale, ranging from “Almost Never” to “Almost Always.” Higher scores reflect increased levels of anxiety. The BAI demonstrates strong psychometric characteristics (α = 0.80), affirming its reliability and validity, and it maintains the reliability in this study (α = 0.87).

GAD-7 is a 7-item questionnaire designed to assess the key symptoms of generalised anxiety disorder and to evaluate its severity in both clinical settings and research contexts (Spitzer et al., 2006). Participants were asked to indicate their experiences over the past two weeks regarding items such as “Worrying too much about different things,” “Being so restless that it is hard to sit still,” and “Not being able to stop or control worrying.” Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale, from 0 (not at all) to 4 (nearly every day). The total score is obtained by summing all the item scores, with higher scores reflecting greater severe anxiety symptoms. The original GAD-7 demonstrates strong internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.92), indicating it is a reliable tool. The Chinese version of the GAD-7 (He et al., 2010), used in this study, also shows solid internal consistency, both when initially validated (Cronbach α = 0.89) and within the current sample (Cronbach α = 0.87).

Primary outcomesThe State-Trait Anxiety Inventory and Beck Anxiety Inventory (see above) were used to measure participants’ anxiety state and anxiety symptoms. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) is a 40-item self-reported questionnaire designed to assess state anxiety (a temporary state influenced by the current situation) and trait anxiety (a general tendency to experience anxiety) (Skapinakis, 2023). It uses a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3 points (from 'not at all' to 'very much so') and scores are calculated by the total, with higher scores indicating higher levels of anxiety. The internal consistency has been found to range between 0.88 in the current sample, indicating good reliability.

Positive Affect Negative Affect Scale. The Chinese Version of Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) was employed to measure participants’ positive and negative affect (Qiu et al., 2008). The PANAS consists of two mood scales measuring positive and negative effects (Watson et al., 1988). Participants respond to items reflecting their feelings over a specific period, such as the past week. Positive affect items include descriptors like “excited” and “enthusiastic,” while negative affect items include terms like “distressed” and “guilty.” Each item is rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely), with higher scores indicating greater levels of positive or negative affect. Its internal consistency ranges from approximately 0.84 to 0.90, making it a reliable measurement tool (Qiu et al., 2008). In the current sample, the internal consistency of the positive affect scale is 0.93 and of the negative affect scale is 0.83.

Secondary outcomesMindful Attention Awareness Scale. The Chinese Version of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) was utilized to evaluate changes in participants' mindfulness over time with good psychometric properties (Cronbach α = 0.85; Deng et al., 2012). The MAAS uses a five-point Likert scale, where participants rate how frequently each statement applies to them, with options ranging from "Almost Always" to "Almost Never" to respond to items such as “I could be experiencing some emotion and not be conscious of it until sometime later”, “I rush through activities without being really attentive to them”. This scale measures how often individuals practice mindfulness and their capacity to sustain awareness of the present moment. In the current sample, the MAAS showed a reliable internal consistency of 0.83.

Nature Relatedness. The Short-Form Nature Relatedness Scale (NR-6) is a six-item questionnaire designed to assess an individual’s emotional connection and identification with the natural environment (Nisbet & Zelenski, 2013). Respondents indicate their level of agreement with each item on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (‘Strongly disagree’) to 5 (‘Strongly agree’). Example items include: “I always think about how my actions affect the environment” and “I feel connected to all living things and the Earth”. The total score is obtained by averaging the ratings across all items, with higher scores indicating a stronger bond with nature. A Chinese version of the NR-6 was adopted for this study, with the translation process involving back-translation by two bilingual authors. In the present study, the scale exhibited good internal consistency (α = 0.86).

Stress. Heart rate was used as a physiological indicator of stress, which triggers the release of hormones such as adrenaline and cortisol, leading to an elevated heart rate as part of the "fight or flight" response (Schiweck et al., 2019). This often manifests as palpitations or tachycardia. A portable biofeedback device was employed to measure the immediate effects of the intervention on participants' stress and anxiety changes (Goessl et al., 2017). This study continuously recorded heart rate using a portable biofeedback device (NeuroHUB by Neuracle), with a finger sensor attached to the participant’s non-dominant hand. Measurements were conducted in a controlled laboratory setting during the pre- and post-intervention phases, following a 5-minute resting baseline. The NeuroHUB system automatically calculated and displayed real-time heart rate values and exported individual data files labelled by participant ID. These output files were subsequently processed and analysed using R to examine immediate changes in physiological stress following the intervention.

The Simulator Sickness Questionnaire. The SSQ is a standardized tool developed to assess the severity of symptoms associated with simulator sickness, which may arise during virtual reality (VR) or other simulation experiences (Kennedy et al., 1993). It captures three primary symptom dimensions: nausea (e.g., “Increased salivation”), ocular disturbances (e.g., “Eyestrain”), and disorientation (e.g., “Dizziness with eyes open”). Participants rate the intensity of these symptoms on a scale from 0 (none) to 3 (severe). The total score is computed by summing these dimension scores, reflecting the overall severity of simulator sickness. The Chinese version of the SSQ was developed using back-translation. The original SSQ has shown strong internal consistency, with reliability coefficients generally exceeding 0.80, and it achieved a reliability coefficient of 0.90 in the current study.

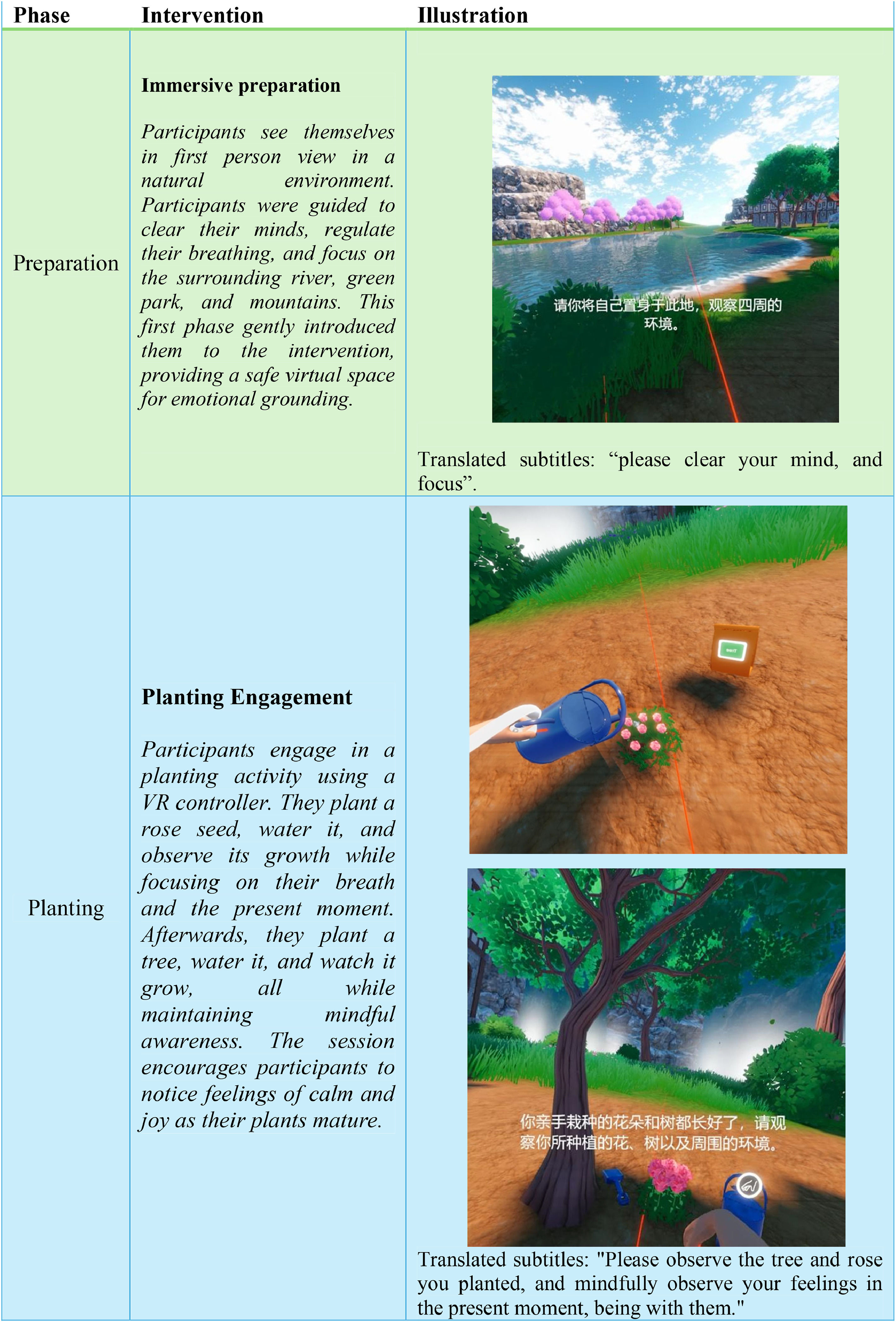

Intervention trailsVR-based Nature Therapy. Based on Attention Restoration Theory (ART; Kaplan, 1995), Stress Reduction Theory (SRT; Ulrich, 1983) and empirical evidence of the benefits of nature-based interventions (Barton & Pretty, 2010; Nature England, 2016; Coventry et al., 2021), we developed a VR-based three-dimensional (3D) interactive nature therapy system to provide participants with an immersive experience through a head-mounted device. Developed on a Windows PC using Unity and Visual Studio, the system runs on Pico series VR headsets and utilises Pico OS (Android-based). Advanced 3D modelling creates realistic nature settings, while human-computer interaction technologies enable natural user engagement with the virtual environment. The system incorporates state-of-the-art speech synthesis for fluid mindfulness guidance and employs scene-switching algorithms for smooth transitions. Developed in C# and supported by Pico SDK and Unity OpenXR Plugin, the software provides meticulously designed natural landscapes, such as stream and lake island settings, to increase users' sense of connection with nature. The VR system used in this study has been registered with the National Copyright Administration of China as computer software (Software Name: Mind Nature -VR-Based Nature and Mindfulness Intervention System 基于虚拟现实的自然与正念心理干预系统V1.0, Registration Number: 2024SR1500302).

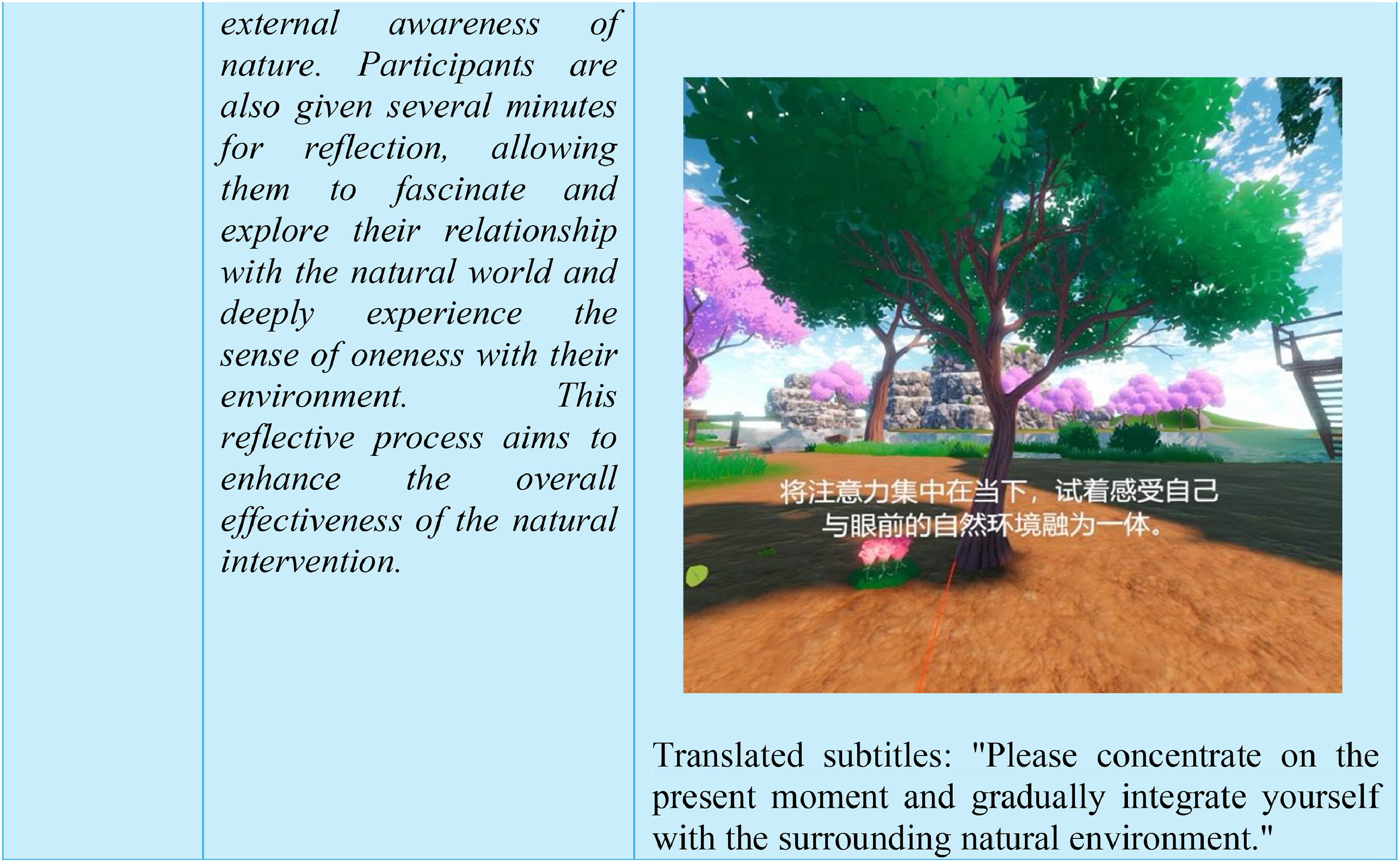

The intervention began with participants standing at the centre of a virtual island surrounded by a lake, river, trees, and a beautiful landscape. Following audio instructions, participants were instructed in planting tasks, they would plant a cluster of flowers and a large tree. During this phase, where they were allowed to move in the laboratory freely, interactive guidance helped them through digging, planting, and watering steps, while mindfulness audio guidance encouraged them to observe their plantings, listen to natural sounds, and connect with their emotions. Participants then rowed around the lake, exploring virtual caves, waterfalls, and other natural features. Throughout this activity, they received mindfulness guidance, focusing on observing and listening to nature, adjusting their breathing, and experiencing their emotions. The intervention concluded with participants returning to the island to revisit their plantings, reflect on their internal and external awareness of being integrated with nature, and experience a sense of fascination and calm in the natural environment (see more details in Table 1).

Placebo Control. The placebo control group consists of a VR beach ball game and activities that mimic outdoor interaction. This allowed us to distinguish the specific effects of the guided nature-based intervention from those arising from general VR engagement or passive exposure to nature-related stimuli. The placebo game lacks the mindfulness guidance and therapeutic components of the nature therapy VR intervention, making it a simple recreational activity without the intended psychological benefits. The duration of the placebo (game) group was carefully matched to that of the nature intervention, lasting around 25 min. This approach balanced the influence of physical activities during the VR intervention and VR game and allowed for a more accurate comparison of the effects across groups. Participants were informed before the game that they could move freely within the laboratory. The game began with participants arriving at a virtual beach, where they could engage in various water-based activities of their choice, such as playing with a frisbee, shooting, or kicking a ball. As they became familiar with the environment, they could swim in the sea and reach a platform equipped with additional recreational features, including water slides, speedboats, and water sports. As the game used in this study was legally purchased, we had full permission to use it for research purposes. However, due to copyright restrictions, we are unable to display specific activities of the placebo group through images.

Inactive Control Group. Participants assigned to the control group did not receive any form of intervention but were asked to complete the same questionnaires as other participants from T1 to T3. The inactive control group served as a baseline to observe natural psychological fluctuations over time, providing a reference point for evaluating intervention effects (Tock et al., 2022; Michopoulos et al., 2021; Karlsson & Bergmark, 2015). However, due to limited research resources, they were not invited to the lab for heart rate measurements, this approach was selected to minimise potential bias from laboratory exposure and to retain a "pure" no-intervention baseline comparison (Schulz et al., 2010). After the study was completed, control group participants were invited to the lab to experience the Mind Nature intervention, but no additional measurements were taken during this session.

ProcedurePotential participants were recruited from universities in Zhejiang Province, China. Participants registered through an online data collection platform and completed the screening test. Their eligibility was evaluated based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as the screening test scores.

Participants were informed that the study involved a virtual reality experience without disclosing the presence of different groups. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions and were unaware of their group allocation; however, researchers were informed of assignments to facilitate study implementation.

All 170 participants who chose not to withdraw finished the entire intervention. Changes to session length or content were not feasible because the VR system was pre-programmed with a set procedure and duration. Participants were aware of the intervention in advance and actively participated in all sessions, despite being aware that engagement parameters were not formally documented due to ethical consideration. To guarantee consistency in intervention exposure among participants, if a session was interrupted, it was restarted with a researcher on nearby providing assistance if needed.

Before the intervention, participants were required to complete a baseline questionnaire (T1) that included measures of anxiety, mood state, mindfulness, and nature-relatedness. At the same time, the researchers collected heart rate as an indicator of stress. Afterwards, researchers provided a tutorial for the VR intervention to ensure participants understood the process of the intervention. Since participants were free to move around the lab during the intervention, the procedure only commenced after confirming that the laboratory environment was clear and safe. During the intervention, researchers monitored participants from a corner of the room without obstructing their movement, ensuring they could help if needed. After the intervention, researchers helped participants remove all VR equipment and collected heart rate data immediately. Also, participants were asked to complete a post-test (T2). If participants felt any discomfort after the VR intervention, they would be taken to a designated resting area to rest. Two weeks after the intervention, participants were asked to fill out a follow-up test (T3). Those who completed all three stages of testing received a compensation of 50 RMB (around US$ 8). The two-week follow-up timeframe was justified to align with clinical diagnostic criteria for anxiety, as tools such as the GAD-7 assess symptom frequency over the past two weeks. This timeframe is widely used in both clinical practice and research to evaluate the presence and severity of anxiety symptoms, making it a reliable period for monitoring changes (Spitzer et al., 2006).

Participants in the experimental and placebo groups attended laboratory sessions where both self-report questionnaires and physiological data, including heart rate, were collected during the pre-and post-intervention phases. In contrast, the control group was designed as a baseline-only condition and did not undergo any intervention or attend laboratory-based sessions. Instead, control participants completed only the self-report assessments remotely at pre- and post-tests. Heart rate data were not collected for this group due to ethical considerations and to avoid introducing potential reactivity effects from laboratory exposure, thereby preserving a clean no-intervention comparison condition.

All intervention and assessment sessions were conducted on weekday afternoons between 1:30 pm and 6:00 pm. This time frame was selected to ensure consistency across participants and to minimise potential confounding factors such as variations in mood, energy level, and sleep patterns that may occur on weekends or outside of standard working hours. By avoiding evening or weekend scheduling, we aimed to reduce the influence of daily routine disruptions on anxiety-related outcomes.

Data analysisData were analysed using R. First, descriptive statistics were reported by mean score, standard deviation and 95 % confidence interval. Normality and homogeneity of variance tests were also used to choose the appropriate method of data analysis. Second, to test that there were no significant group differences in dependent variables at baseline, a series of one-way ANOVA were employed. Third, to test whether Mind Nature intervention effectively alleviated participants’ anxiety symptoms, trait-state anxiety, and negative mood while improving positive mood, mindfulness, and nature-relatedness, repeated mixed-ANOVA was used to evaluate such effects from T1 to T3. To control for Type I error resulting from multiple comparisons across groups and outcomes, we applied the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to adjust p-values, using a false discovery rate of 0.05. This approach balances error control with statistical power and is suitable for studies involving multiple related hypothesis tests. Additionally, an independent t-test was conducted to assess differences in heart rate and VR-induced sickness, which were measured only at time points T1 and T2. The significance level for all tests was set at less than 0.05. The independent variable was the group assignment, and the dependent variables were changes in anxiety symptoms, state-trait anxiety, positive and negative mood, mindfulness, nature-relatedness, heart rate, and simulator sickness across timepoints. Due to the dropout rate from T1 to T3, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to confirm the robustness of the findings.

EthicsThe research adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and ethical guidelines and was approved by the University’s Human Research Ethics Committee via the institutional platform formally referred to as the Animal Experimental Ethical Inspection Form (No. WZU-2024–032). Before participating, all individuals received an electronic participant information sheet outlining the purpose of the study, the nature of the intervention, expected duration, potential risks and benefits, and assurances regarding confidentiality and data handling. Participants were informed that their participation was voluntary and that they had the right to withdraw at any time without consequence. To minimise expectancy effects and reduce bias, the study was described in general terms as an investigation into “VR experience,” without revealing the specific hypotheses. Participants signed the consent form once they fully understood the study and agreed to their participation.

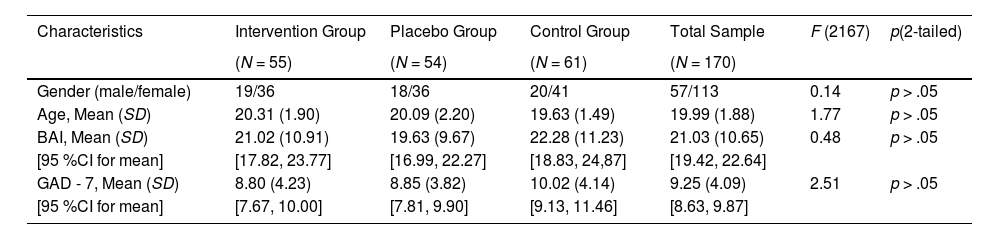

ResultsDescriptive analysesTable 2 presents the demographic characteristics and baseline data of the three groups before the intervention. There were no differences between gender, F (2, 167) = 0.14, p = .86, age, F (2, 167) = 1.77, p = .17, and pre-study anxiety based on BAI, F (2, 167) = 0.48, p = .62, and GAD-7, F (2, 167) = 2.51, p = .85.

Demographic characteristics, baseline measure of participants (N = 170).

Note. BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory; GAD - 7: General Anxiety Disorder - 7.

Normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests across all variables and time points, with some variables showing no significant deviation (e.g., pre-intervention MAAS: D = 0.052, p > .05; post-intervention anxiety: D = 0.265, p > .05). Minor deviations in a few variables were considered acceptable given the large sample size, as ANOVA is robust to mild non-normality (Schmider et al., 2010). Levene’s test confirmed the homogeneity of variance for most variables (e.g., pre-intervention MAAS: F = 0.268, p = .765). Based on baseline screening using the BAI and GAD-7, the included participants were identified as experiencing mild to moderate anxiety at T1. Moreover, it has shown that anxiety, F (2, 167) = 0.24, p = .79, state and trait anxiety, F (2, 167) = 0.94, p = .40, mindfulness, F (2, 167) = 0.61, p = .55, positive affect, F (2, 167) = 2.07, p = .13, negative affect, F (2, 167) = 0.20, p = .82, and nature relatedness, F (2, 167) = 0.53, p = .59 were not significantly different among three groups at baseline (T1). Moreover, there were no differences between the intervention group and placebo group in heart rate, t (107) = −0.11, p = .92 at T1. This indicated that those groups were matched at baseline and successfully randomised (Table 2).

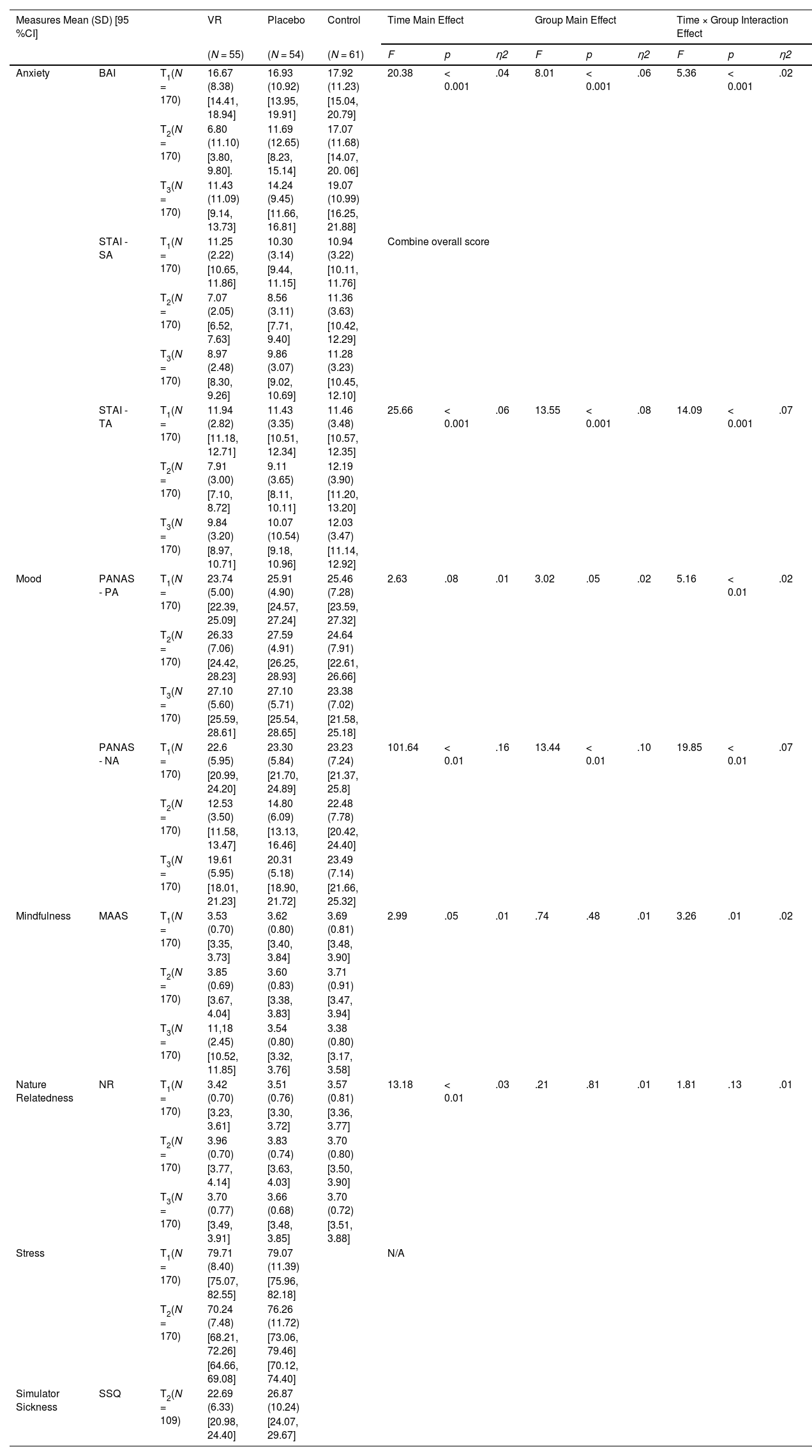

The effectiveness of the interventionThe 3 (Group: Intervention, Placebo, Control) × 3 (Time: T1, T2, T3) ANOVAs with repeated measures evaluated the effect of VR-based nature therapy on anxiety, mood, mindfulness and nature-relatedness. A 2 (Group: Nature, Placebo) × 2 (Time: T1, T2) ANOVAs evaluated the changes in stress (i.e. Heart rate) before and after the intervention. An Independent t-test was conducted for simulator sickness evaluation. The means and standard deviations for relevant variables are presented in Table 3.

Summary results table of outcome means, SD, 95 %CI, and effects.

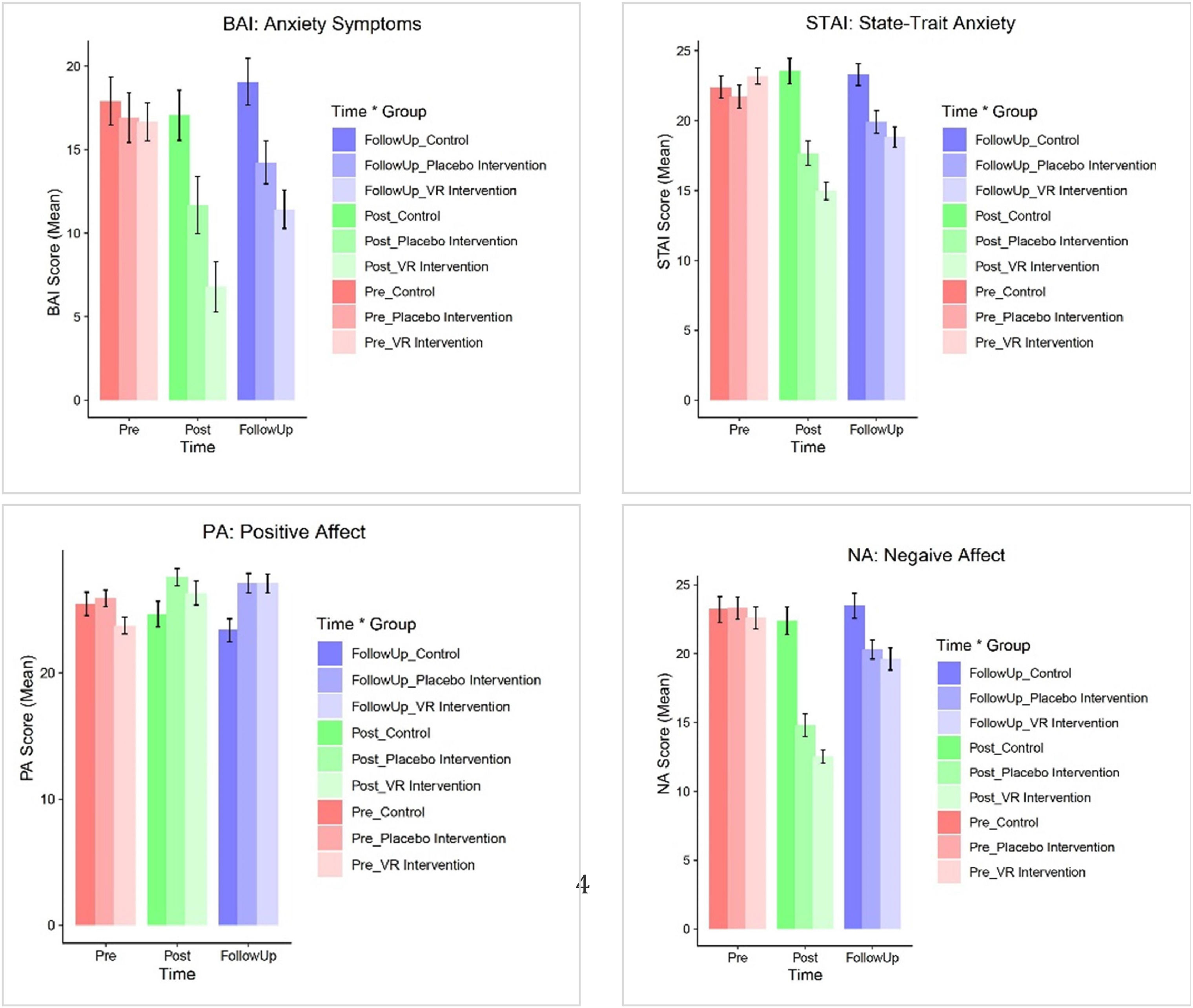

Anxiety. There was a significant main effect of time on the reduction of anxiety symptoms, F (2, 332) = 20.38, p < .001, η² = 0.04, suggesting significant changes in anxiety across time points. A significant main effect of group, F (2, 166) = 8.01, p < .001, η² = 0.06 was also found, indicating that anxiety levels varied across the three groups (see more details in Fig. 2). Additionally, there was a significant interaction effect between group and time, F (4, 332) = 5.36, p < .001, η² = 0.02. This indicates that the pattern of change in anxiety symptoms over time differed among the groups. Simple main effect analyses of time within each group revealed significant decreases in anxiety for the VR Intervention group from T1 to T2 (p < .001) and from T1 to T3 (p = .021). However, a slight but significant increase in anxiety was observed from T2 to T3 (p = .001). The Placebo control group exhibited a significant reduction in anxiety from T1 to T2 (p < .05) but no significant changes between T2 and T3 (p = .334). For the Inactive control group, there were no significant changes in anxiety between any of the time points (all ps > 0.05). Simple main effect analyses of group differences within each time point indicated no significant differences in anxiety between groups at T1 (all ps > 0.05). At T2, the VR Intervention group reported significantly lower anxiety compared to both the inactive control and placebo group (ps < 0.05). At T3, VR Intervention group continuing to exhibit lower anxiety levels than the other two groups, but no significant differences were found between VR intervention group and Placebo group (p = .5), but significant differences were found between VR intervention group and Control group (p < 0.01). However, significant differences were found between the Control and Placebo groups at T3 (p = .04).

To account for multiple comparisons in the simple main effect tests, the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure was applied to control the false discovery rate (FDR) at 0.05. All key group differences reported above remained significant after correction, supporting the robustness of the observed effects.

For state-trait anxiety, the combined score was calculated to present participants’ general reduction in anxiety. The results revealed significant main effects of group, F (2, 166) = 13.55, p < .001, η² = 0.08, and time, F (2, 332) = 25.66, p < .001, η² = 0.06. More importantly, there was a significant Group × Time interaction effect, F (4, 332) = 14.09, p < .001, η² = 0.07, indicating that the change in anxiety levels over time varied across groups. Simple main effect analysis showed that for the VR Intervention group, anxiety levels decreased significantly from T1 to T2 (p < .001) and remained lower at T3 (p < .01). In the Placebo group, anxiety significantly decreased from T1 to T2 (p < .001) but showed no significant change from T2 to T3 (p = .06). By contrast, anxiety levels in the Control group did not change significantly between time points (all ps > 0.05). Furthermore, at T1, there were no significant group differences (all ps > 0.05). At T2, the VR intervention group showed significantly lower anxiety than both Placebo group (p < .001) and the Control (p < .001). The Placebo group also showed lower anxiety than the Control group (p < .01). At T3, the VR intervention group maintained lower anxiety compared to the Placebo group (p = .01) and Control group (p < .01). However, there was no significant difference between the Control and Placebo groups (p > .05). We applied the Benjamini-Hochberg correction for the simple effect tests. The key results remained statistically significant after FDR adjustment, reinforcing the reliability of the group differences over time. The results indicate that the VR intervention group was the most effective in reducing anxiety, with significant decreases from T1 to T2, and the effect persisting at T3. In contrast, the Placebo group showed moderate but less durable effects. No meaningful change was observed in the Control group over time, highlighting the specific efficacy of the VR intervention (see Fig. 2).

Mood. There was no main effect of group for positive affect, F (2, 166) = 3.02, p = .051, with a small effect size, η² = 0.02. The main effect of time was also non-significant after sphericity corrections, F (2, 332) = 2.63, p = .08, with small effect size, η² = 0.01. A significant interaction effect was found, F (4, 332) = 5.16, p < .01), indicating that the effect of time on positive affect differed by group, with a small to moderate effect size, η² = 0.02. Given the significant Group × Time interaction, we performed simple main effect analyses to further explore group differences at each time point and the changes over time within each group. There was no significant difference between the Control and VR Intervention (p = .50)) or between the Placebo and VR intervention group (p = .89). No significant group differences were observed, all ps > 0.22 at T1. Significant differences were found between the Control and Placebo groups (p = .04). At T3, both the Control versus Placebo intervention (p = .01) and Control versus VR Intervention (p = .01) comparisons were significant, suggesting sustained improvements in positive affect in the Intervention group. No difference was found between the Placebo and VR groups (p = 1.0). Furthermore, for participants in VR Intervention group and Placebo group, positive affect significantly increased from T1 to T3, (ps < 0.01). By contrast, there was no significant change in positive affect for the Control group over time, (p > .05). Although no main effects of Group or Time were detected, the significant interaction suggests that the group conditions (especially at T3) had a differential impact on positive affect, with both the Placebo and VR Intervention groups outperforming the Control group. However, no significant difference was found between the VR Intervention and Placebo groups, indicating comparable efficacy (see Fig. 2).

For negative affect, there was a significant main effect of the group, F (2, 166) = 13.44, p < .01, with a medium effect size, η² = 0.10. A significant main effect of time was also found, F (2, 332) = 101.64, p < .01, with a moderate effect size, η² = 0.16. There was a significant interaction effect, F (4, 332) = 19.85, p < .01, with a small to moderate effect size, η² = 0.07. This suggests that the effect of time on negative affect differed between the groups. A simple main effect analysis revealed no significant group differences at T1, (all ps > 0.05). At T2, both the Control versus Placebo (p < .01) and Control vs VR Intervention group (p < .01) comparisons were significant, indicating lower negative affect in the Placebo and VR Intervention groups. No significant difference was found between the VR Intervention and Placebo groups (p = .177). Significant differences were maintained between the Control and both Placebo (p = .02) and VR Intervention (p = .01), and no significant difference between the Placebo and VR intervention (p = 1.0) at T3. Additionally, for the VR intervention group, similar patterns were observed, with significant reductions from T1 to T2 and T1 to T3 (p < .01). For the Placebo group, NA significantly decreased from T1 to T2 (p < .01)) and T1 to T3 (p < .01). Participants in control group showed stable NA over time, (p > .05). The results suggest that VR intervention and Placebo groups were effective in reducing NA, with significant improvements maintained through the follow-up period (see Fig. 2).

Secondary outcomesMindfulness. There was a significant main effect of time, F (2, 332) = 2.99, p = .05, η² = 0.01, although this effect was marginal. There was no main effect of group, F (2, 166) = 0.74, p = .48, η² = 0.01, indicating no overall differences in MAAS scores across the three groups. However, the group × time interaction was significant, F (4, 332) = 3.26, p = .01, η² = 0.02, suggesting that changes in mindfulness levels over time varied between groups. Simple main effect analysis showed that no significant differences were observed between any of the groups at T1 (all p > .850). At T2, no significant contrasts emerged (all p > .309), although the Placebo group showed a trend towards higher scores than the VR-Intervention group. At T3, the Control group scored significantly higher than the VR Intervention group (p = .034). No other contrasts were significant. These findings suggest that while overall differences between groups were limited, VR intervention may lead to lower MAAS scores compared to the control group over time (see Fig. 3).

Nature relatedness. There was a significant main effect of time, F (2, 332) = 13.18, p < .01, η² = 0.03, indicating that nature relatedness scores changed across the three time points. However, there was no significant main effect of group, F (2, 166) = 0.21, p = .81, η² = 0.01, suggesting that nature relatedness scores did not differ between the intervention groups. Furthermore, the group × time interaction was not significant, F (4, 332) = 1.81, p = .13, η² = 0.01, indicating that the patterns of nature relatedness score changes over time were similar across groups. Post-hoc tests found that nature relatedness scores significantly decreased from T1 to T2 (p < .01). A significant decrease in nature relatedness scores was also observed from T1 to T3 (p = .003). However, no significant difference was found from T2 to T3 (p = .30). Post-hoc comparisons for the main effect of group revealed no significant differences between any pair of intervention groups across all time points (all ps >0.05). Indicating that nature relatedness scores significantly decreased over time, particularly from T1 to T2 and T1 to T3. However, the lack of significant differences between groups and the non-significant interaction effect suggests that the intervention type did not have a distinct impact on NR scores. The overall decline in nature relatedness may reflect external factors or a time-related effect across all participants, regardless of the intervention group (see Fig. 3).

Stress. There was no significant main effect of the group, F (1, 107) = 2.74, p = .10, η2 = 0.03, suggesting that, on average, the intervention and placebo groups did not differ significantly in their overall heart rate levels. A significant main effect of time was also observed, F (1, 107) = 29.13, p < .001, η2 = 0.21, showing that heart rate decreased across all participants over time. There was a significant interaction effect between time and group for heart rate, F (1, 107) = 7.45, p = .01, η2 = 0.07, indicating that the change in heart rate over time differed between groups, VR Intervention group reduced more than the Placebo group (see Fig. 3).

Simulator Sickness. The VR Intervention group experienced significantly more simulator sickness (M = 22.69, SD = 6.33) than the Placebo group (M = 26.87, SD = 10.24). Furthermore, there was significant difference in simulator sickness between the VR Intervention group and the Placebo group, t (107) = −2.57, p = .01, which indicates that the simulator sickness symptoms of the Intervention group were significantly lower than those of the Placebo group.

Sensitivity testTo assess the robustness of the findings, a sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding data points beyond three standard deviations from the mean. Although few participants dropped out between T1 and T3, the overall results remained largely consistent with the primary analysis. The main effects of group, time, and their interaction on anxiety symptoms, state-trait anxiety, negative affect, and mindfulness were still significant (all ps < 0.01). However, for positive affect, the sensitivity analysis revealed significant main effects for both group and time, along with a significant interaction effect (all ps < 0.05), contrasting with the primary analysis, which found only a significant interaction effect. Similarly, the interaction effect on nature-relatedness became significant after outliers were removed, suggesting that extreme values had masked the relationship between group and time. This highlights the significance of sensitivity analysis for identifying subtle modifications and confirming the robustness of findings. We also conducted exploratory analyses by including gender as a covariate and checking for potential interaction patterns. No significant moderation effects by gender were observed (ps > 0.05), although the relatively small male subgroup limits the statistical power to draw definitive conclusions. These findings should be interpreted with caution and highlight the need for future studies with more gender-balanced samples.

DiscussionThis study employed a randomised control trial to investigate the intervention efficacy of Mind Nature by examining its effects on anxiety, mood, mindfulness, and nature-relatedness. The results confirm the effectiveness of Mind Nature in reducing anxiety symptoms, overall state-trait anxiety, and negative affect to a greater extent than the Placebo group and Control group, with reductions maintained at 14-day follow-ups.

Mind Nature led to a substantial reduction in anxiety symptoms, exceeding both the Control group and the Placebo group. Participants' anxiety symptoms decreased from the baseline to the post-test and the 2-week follow-up. Similarly, participants in Mind Nature showed a reduction of state-trait anxiety with a large effect size, significantly larger than that observed in the other groups. Moreover, the effect of the Mind Nature was maintained for two weeks in overall state anxiety and trait anxiety. This demonstrates a sustained reduction in both anxiety symptoms and state-trait anxiety, indicating that the Mind Nature intervention not only addresses an immediate, large effect on anxiety but also contributes to a longer-term alleviation of anxiety symptoms. This is due to Mind Nature incorporating an immersive VR environment featuring vivid, aesthetically pleasing natural landscapes and interactive nature activities, such as planting and rowing on a lake. These elements enhanced user engagement and increased the therapeutic potential of the intervention.

These findings align with previous research indicating that VR-based nature therapies can effectively alleviate anxiety symptoms (Li et al., 2021; Spano et al., 2021). However, earlier studies on VR-based nature therapy varied in their levels of immersion—some employed 2D environments while others used 3D—while some studies only utilised brief 6-minute VR nature tours. Despite this variation, many studies lacked a rationale for the design of nature content and the level of interactive engagement. Furthermore, most VR nature intervention studies primarily focused on measuring participants' stress, mood, and well-being, and only a limited number have investigated the impact of VR-based nature therapy on the various facets of anxiety. In contrast, Mind Nature incorporates interactive and immersive nature activities that facilitate full engagement with the environment. Consequently, this study provides compelling evidence for the efficacy of VR-based nature therapy in reducing anxiety symptoms, representing a significant contribution to the field.

In terms of mood changes, the findings revealed a significant reduction in negative affect for participants who engaged with Mind Nature, with a significant decrease from T1 to T2, and a sustained significant reduction at T3. This reduction was greater than that observed in both the Placebo and Control groups, demonstrating a substantial positive effect of the intervention over time. Similarly, Mind Nature led to an improvement in positive affect from T1 to T2. However, the changes in positive affect did not differ significantly between the three groups, and no lasting effects were observed at T3. This is consistent with a previous study that found short VR-based nature exposure can effectively improve young adults’ positive mood (Browning et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021). However, as limited research with a similar design has been found, non-significant group differences might be explained by the possibility that all participants experienced a general uplift in mood due to the immersive nature of the virtual environments, regardless of the specific therapeutic intention behind the interventions.

For mindfulness, our findings indicate that participants in the VR Intervention group experienced a significant improvement from T1 to T2. However, no significant differences among groups were observed, suggesting that while the intervention effectively enhanced participants’ mindfulness—likely due to the inclusion of mindfulness audio guidance—it did not produce varying outcomes across groups. This lack of between-group differences may be attributed to the intervention's focus on mindfulness guidance to foster both internal and external awareness of the natural environment, which in turn led to improved mental health outcomes.

Surprisingly, participants in the Mind Nature intervention did not show significant improvement in nature-relatedness, as measured by the Nature Relatedness Scale-6 (NR-6), and no group differences were detected. This lack of improvement may be due to several factors, including the brief duration of the intervention, which might not have allowed enough time for meaningful changes in nature-relatedness that typically require deeper engagement with natural environments. Additionally, the Placebo group’s experience of a VR game set in a natural context could have fostered similar feelings of connection to nature, potentially masking differences between the groups. While online environmental programs can influence emotions, outdoor experiences in natural settings may be more effective in strengthening a person's connection with nature (Arbuthnott et al., 2022). Additionally, the NR-6 scale may not effectively capture short-term changes in nature-relatedness, suggesting that future research should consider longer intervention durations or alternative measures that better reflect immediate nature engagement. Despite no significant changes in nature-relatedness, the nature VR group showed reduced anxiety and improved well-being in the present study. This indicates that the positive effects may not solely stem from an increased connection with nature. It is plausible that decentering, where individuals gain psychological distance from distressing thoughts and emotions, plays a role (Vyas et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2024). Engaging with immersive natural environments may shift attentional focus away from internal rumination towards calming external sensory stimuli (O’Meara et al., 2020). This experiential detachment is associated with improved emotion regulation and psychological flexibility, both of which are relevant to reducing anxiety symptoms (Gamaiunova et al., 2024). Future research should explore these cognitive mechanisms further, potentially by incorporating process measures, including decentering or mindfulness during the intervention.

In terms of stress, the health benefits of beaches have been shown to significantly reduce perceived stress and sympathetic nervous system activity, particularly by lowering breathing rates, compared to urban and green environments (Hooyberg et al., 2023). Since we only assessed heart rate—a crucial physiological marker of stress and anxiety—for the VR Intervention and Placebo groups from T1 to T2, our results are only partially consistent with this study. All individuals' heart rates decreased indicating a decrease in physiological arousal, which is consistent with a previous within-subjective designed study that the VR forest intervention can significantly decrease one’s heart rate (Yu et al., 2018). Nevertheless, the fact that there were no significant differences between the VR Intervention and Placebo groups implies that anxiety may be reduced by any therapy. This raises the concern of whether VR environments, regardless of their intended therapeutic use, could induce comparable physiological reactions. The main impact of time raises uncertainty on the hypothesis that only specific treatments may cause meaningful physiological changes by highlighting the possibility that a natural decrease in stress levels could also contribute to heart rate reduction. Future studies must examine the processes behind these patterns and how using virtual worlds may promote relaxation and improve anxiety management techniques.

Cybersickness is a common complication of head-mounted display (HMD) virtual reality devices, as they partially remove visual cues from the real world and involve high levels of immersion, leading to a mismatch between visual and vestibular systems (White et al., 2018). However, our study found that Mind Nature did not induce nausea or discomfort among participants. Although SSQ totals may appear numerically elevated, such values are commonly observed in VR studies and should not be interpreted as direct indicators of clinical severity. Crucially, no participants withdrew or reported intolerable discomfort, confirming that both conditions were safe and that the Intervention group experienced significantly fewer symptoms than the Placebo group. Moreover, the placebo VR condition may have produced improvements due to non-specific effects such as novelty, distraction, or induced relaxation, as noted in other immersive technology studies. Future studies should also incorporate this consideration and use robust empirical designs to compare the psychophysical benefits of nature therapy in real versus other virtual environments. Future studies should also incorporate this consideration and use robust empirical designs to compare the psychophysical benefits of nature therapy in real versus virtual environments.

In summary, our findings overall align with a previous systematic review of 59 studies, which demonstrated that virtual nature positively impacts anxiety (Spano et al., 2021). Meanwhile, it further supports the therapeutic potential of using VR to present immersive environments for mental health, as they are consistent with recent VR interventions for mental health, such as those that use progressive muscle relaxation or guided imagery (Pardini et al., 2024). Mind Nature builds on this by using a larger sample size and a robust RCT design to effectively evaluate the impact of VR-based nature therapy in non-clinical but anxious populations. A related study explored the key factors for designing a VR-based nature system to reduce stress, identifying visual attraction, environment setting, user comfort, and interaction as essential elements for creating effective virtual environments for stress therapy (Zaharuddin et al., 2019).

Limitations and further directionsWhile this study is the first to test a VR-based nature therapy with conclusive phases of nature therapy, several limitations need to be addressed to enhance the robustness of the findings.

First, the sample consisted solely of university students, limiting the generalisability of the results. Future studies should involve more diverse demographics and include participants with varying levels of anxiety and mood disorders, encompassing different ages and socioeconomic backgrounds to ensure broader applicability. Second, the follow-up period was limited to two weeks. Although the GAD-7 and SAI questionnaires asked participants to report symptoms from the past two weeks, future studies should incorporate additional follow-up points—such as one week, two weeks, and one month—to more thoroughly capture changes in the intervention's effects over time. Third, the study only collected heart rate data as a physiological indicator of stress in the VR Intervention and Placebo groups, not the Control group. Future studies should address this limitation by including physiological measures for Control group participants. Future studies should include heart rate variability (HRV) measures to better assess long-term stress regulation.

Third, although we recruited 236 participants at baseline to account for potential attrition, approximately 28 % dropped out, leaving 170 participants in the final analysis. This dropout rate is consistent with previous psychological intervention studies (Iliakis et al., 2021). However, as missing data were not imputed, the potential for attrition bias remains, but sensitivity analyses indicated no significant bias in the results. Future studies may benefit from using imputation methods to further assess the impact of missing data. Furthermore, although participants were drawn from multiple universities within a shared university town and tested individually, we acknowledge the possibility of contamination due to informal peer interactions. While the single-session design and random assignment helped mitigate this risk, future studies could consider using cluster randomisation or instructing participants to avoid discussing the intervention. In addition to this, future studies are also encouraged to increase the frequency of interventions to examine long-term effects and identify the optimal "dose" for the best outcomes. Further versions of Mind Nature could also incorporate additional phases and a wider variety of nature environments. While Mind Nature shows promise as an innovative intervention for reducing anxiety and improving mood in university students, addressing these limitations through rigorous, diverse, and methodologically sound research is essential to solidifying its efficacy and expanding its clinical use.

It should also be noted that the gender distribution in the current study was unbalanced, with a higher proportion of female participants. This reflects a broader pattern in mental health research, where women are more likely to seek psychological support and volunteer for intervention studies (Juvrud et al., 2017). Due to the limited sample size within gender subgroups, we did not conduct formal moderator analyses to explore potential gender differences in intervention effectiveness. Future research with larger and more balanced samples is needed to examine whether gender moderates the psychological outcomes of VR-based interventions. Lastly, although care was taken to standardise the time of day for intervention delivery, the study did not systematically account for potential real-world confounding factors, including academic pressure, personal stressors, or coinciding examination periods. These external influences may have had an unintended impact on participants’ psychological states. Future studies would benefit from collecting contextual data on participants' academic calendars, sleep patterns, or stress exposure and could consider implementing longitudinal or repeated-exposure designs to better isolate the effects of the intervention under varying real-life conditions.

Implications for clinical practiseThis study addresses the importance of extending mental health interventions beyond clinical populations, demonstrating that VR-based nature therapy can effectively reduce both state and trait anxiety in university students. Subclinical anxiety symptoms, which impair academic performance and well-being, highlight the need for early intervention to prevent progression to clinical disorders (Duffy et al., 2019). The observed reductions in both acute (state) and chronic (trait) anxiety highlight the potential of immersive therapies, such as Mind Nature, to deliver immediate and lasting benefits.

Mind Nature provides an accessible and engaging solution by immersing students in interactive nature activities, making it a practical complement to traditional treatments. This approach is particularly valuable for students with limited access to natural environments or mental health care. As mental health challenges among university students continue to rise, scalable interventions like this can help address the gap between growing demand and limited resources (Spano et al., 2021).

Designed with user safety and engagement in mind, Mind Nature includes post-intervention assessments for side effects, such as nausea, ensuring a secure and effective experience. It offers university support professionals a practical tool to alleviate anxiety and negative moods, helping students manage symptoms before more severe conditions develop.

ConclusionBy using VR applications with university students, this study showed that Mind Nature is an effective intervention for reducing anxiety, negative mood, and stress in anxious university students, while also potentially improving positive mood. The findings highlight the intervention’s utility in supporting student mental health and well-being. Mind Nature could be integrated into traditional therapy or used as an independent tool to address anxiety, stress, and low mood, offering a practical and accessible approach for students with limited access to mental health resources or natural environments. This intervention offers a practical and engaging solution for improving mental health outcomes, making it highly applicable within university contexts. Future research should address the limitations of this study, such as the need for more robust measurements and diverse sampling. Expanding its application to varied populations and exploring different intervention protocols will help refine and validate its broader effectiveness.

Funding sourceThis research was conducted with institutional support from the Talent Recruitment Research Start-up Fund of Wenzhou University for laboratory access and ethical review. No direct financial support was received for VR development and publication costs.

I have nothing to declare.

We would like to thank all the participants in this study. We also thank Ms. Hanyun Zhang and Ms. Ruoyi Xiang for their support in participant management and recruitment for this project.