Existing diagnostic categories of teen dysfunction often refer to hypothetical biological or developmental factors, even though teen dysfunction is often absent in many non-Western cultures. Diagnostic categories of this sort do not do justice to the social causes of many teen problems in the United States (U.S.) and other Western countries. To put more emphasis on known cultural causes of teen dysfunction, we propose adopting an ecologically-based diagnostic category we call “extended childhood disorder” (ECD), characterized by (1) excessive and sometimes harmful involvement with peers, (2) conflict centering around control issues with authority figures, and (3) mood problems centering around control issues with authority figures.

Method5198 individuals were evaluated, either by themselves or by therapists, counselors, teachers, or parents: a diverse group of 3147 females, 1750 males, and 301 others, mean age 23.4. 54.3 % of the participants were from the U.S., and the remaining 46.7 % were English speakers in 74 other countries.

ResultsTotal scores on a diagnostic test of ECD were negatively correlated with level of happiness and positively correlated with levels of anger, depression, and anxiety, whether reported by self or others (note that higher scores on the ECDI indicate greater dysfunction). Total scores were also predictive of 13 clinically significant criterion variables. Notably, prevalence of ECD in our sample roughly matched the 2010 National Comorbidity Survey estimates of the prevalence of teen disorders in the U.S.

ConclusionThe ECD diagnostic category should be considered as a viable alternative to current diagnoses of teen problems that emphasize hypothetical endemic or neural deficits.

In the United States (U.S.) and most other Western countries, the teen years are often characterized as a time of turmoil. In the U.S., this characterization has its roots in a landmark book – Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion, and Education – published in 1904 by G. Stanley Hall, a professor of psychology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. According to Hall, teens are reenacting a time when our distant ancestors were barbaric and tribal.

Hall’s views on teens were shaped largely by two factors, each of which, in our view, led him to adopt faulty beliefs about the teen years. First, his views were driven in large part by the packs of unruly young immigrants who crowded the streets of Baltimore and other fast growing cities in a rapidly industrializing United States (Gibson & Jung, 2006; Stave, 1972). Between 1820 and 1880, the population of New York City mushroomed from 123,706 to 1,206,299 (Rosenwaike, 1972). In the first decade of the 20th century, 8.8 million people immigrated to the U.S., boosting a country of 60 million people by almost 15 % and straining resources to the breaking point, especially in the rapidly growing cities (Rumbaut, 1990; Simkin, 1997; U.S. Census Bureau, 1901; Warner, 1995). Young “hooligans” were especially visible and troublesome, because they had a high rate of unemployment and because nationwide mandatory education laws were not yet in place (Epstein, 2010; Lleras-Muney, 2002).

Second, Hall’s thinking was shaped by “recapitulation theory,” a concept from biology that was popular around the turn of the twentieth century. According to Ernst Haeckel’s “biogenetic law,” which he first proposed in his (Haeckel, 1866) book, General Morphology of Organisms, and expanded upon in his 1868 book, The History of Creation, “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” (Haeckel, 1880). In other words, the development of the individual mimics the development of its species, or, as Hall put it, “the individual recapitulates the growth stages of his race” (Hall, 1904, vol. I, p. 55), and children “in their incomplete stage of development are nearer the animals in some respect than they are to adults” (Hall, 1904, vol. II, p. 221).

The validity of Haeckel’s theory was questioned by the late 1800s and ultimately rejected by biologists, in part because he was accused of and ultimately admitted to faking some of the diagrams in his 1868 book (Brody, 2002; cf. “Accused of fraud,” 1910; Assmuth, 1915; Pennisi, 1997; Richardson et al., 1997, 1998). Unfortunately, the psychologists who had enthusiastically adopted Hall’s characterization of adolescence never got the message from the biologists. That is, even though Hall’s theory was based on Haeckel’s, it survived the fall of Haeckel’s theory without suffering a scratch, and Hall’s views about teens still dominate how mental health professionals characterize the teen years.

Hall’s characterization of adolescence rapidly came to dominate the thinking of experts in multiple fields, in part because of multiple societal changes that introduced more and more chaos and stress into the lives of young people as the 20th century progressed, and his ideas spread to other Western countries as industrialization expanded. A 2012 study suggested that the Sturm und Drang (storm and stress) characterization of the teen years was shared by college students in 26 countries, with adolescents generally viewed as “impulsive, preferring excitement and novelty, and rebellious and undisciplined, relative to adults” (Chan et al., 2012, p. 1063) and with “consensual stereotypes tend[ing] to exaggerate personality differences among age groups” (Chan et al., 2012, p. 1050). Other studies show that adolescent stereotypes (such as rebelliousness) influence “explicit evaluations of teens unconsciously and unintentionally” (Gross & Hardin, 2007, p. 140), with Americans tending to use more socially-negative words to describe people of this age group than adults in other countries do (Boduroglu et al., 2006; Gross & Hardin, 2007).

Modern mainstream media reflect these stereotypical characterizations of adolescents, often reporting neuroscientific findings that appear to support these characterizations. Headlines about teens describe them as “moody, lazy, selfish nightmares” (Forster, 2015; Rose, 2019), “impulsive” (Gross, 2015; Underwood, 2013), and “wild” (Allen, 2014; Pierre, 2017). In an essay criticizing the usual teen stereotype, Romer (2017) confirms that adolescents are typically characterized as “impulsive, reckless and emotionally unstable” – traits that are often attributed to “raging hormones” or an imbalance in brain development.

Are our teens actually in turmoil? Unfortunately, the answer seems to be yes. According to the 2010 National Comorbidity Survey (Merikangas et al., 2010) – the most recent survey of its kind conducted as of this writing (April 18, 2025) – 49.5 % of teens were diagnosable under DSM-IV guidelines at that time with at least one emotional, behavioral, or substance abuse disorder (cf. Essau & de la Torre-Luque, 2019; Kessler et al., 2012). In 2021, accidental injury was the leading cause of death of young people between ages 10 and 19 in the United States, with death by violence (homicide) and suicide following, respectively (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021a). That same year, 22.2 % of high school students in the U.S. reported that they had seriously considered suicide within the past year, an increasing trend since 2009 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021b).

With the advancement of imaging technology in the 1970s, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and the functional MRI (fMRI), some neuroscientists were quick to blame teen turmoil on the brain (Baird et al., 1998; Stein, 1998). By the early 2000s, the “teen brain” had become an icon in modern culture, with cover stories in TIME magazine (Wallis & Dell, 2004), Scientific American Mind (Sabbagh, 2006), National Geographic (Dobbs, 2011), and U.S. News & World Report (Brownlee, 1999), along with several books having this theme (e.g., Jensen & Nutt, 2015; Siegel, 2014).

Teen brains look different in some respects from the brains of young children and the brains of older adults; the brain changes throughout life, without doubt (Bethlehem et al., 2022; Hedman et al., 2011), so the teen brain must look distinctive in some respects. This developmental process sheds no light, however, on a possible causal link between teen turmoil and properties of the teen brain. As so often happens, the correlation has gotten people confused. If teens are in turmoil and teen brains are different, surely, some people thought, the brain must be the culprit. According to neuroscientist Gregory S. Berns, “Nobody denies that the brain develops or that teens take risks, but how the two observations got intertwined is beyond me” (Berns et al., 2009; cf. Epstein & Ong, 2009). This kind of shoddy thinking underlies what some experts call the “brain overclaim syndrome” (Morse, 2006).

This view of teen turmoil helped to create a major new market for the pharmaceutical companies. With millions of anxious, inattentive, depressed, and angry teens needing help, beginning in the 1950s, pharmaceutical companies began to aggressively repurpose antidepressants, stimulants, and anxiolytics for younger and younger people (Herzberg, 2009). By 2004, more money was being spent on prescription psychotropic drugs for teens in the U.S. than on all other prescription drugs for teens combined, and that includes antibiotics and acne medication (Johnson, 2004). According to a CDC data brief, in 2021, 10.7 % of young people in the U.S. between ages 12 and 17 had taken medication in the past 12 months for their mental health (Zablotsky & Ng, 2023). These medications are often prescribed for off-label uses with young people (Kearns & Hawley, 2014; Rafaniello et al., 2020; Sohn et al., 2016) and in situations in which “use only partially aligns with the psychiatric disorders for which [these medications] have been demonstrated to be effective in clinical trials” (Olfson et al., 2013). Of even greater concern, the adverse side effects and long-term risks of some of the psychotropic drugs prescribed for teens have barely been studied (Rafaniello et al., 2020; Solmi et al., 2020).

Cultural and ecological alternativesThe century-old biological perspective on teen problems is so deeply entrenched in Western culture that it is difficult to consider alternatives. But two long traditions of scholarship – one from the field of anthropology and the other from the field of history – suggest that the biological perspective is deeply flawed. Anthropological research tells us that Western-style teen problems are completely absent in many cultures around the world, most of which don’t even have a term for “adolescence” (Dasen, 2000; Ember et al., 2017; Schlegel & Barry, 1991; Stone & Church, 1957). And historians tell us that prior to the onset of the industrial revolution – in the U.S., that was roughly the period from the late 19th century to the early 20th century – adolescence as a separate and distinct period of life did not exist (Epstein, 2010; Hanawalt, 1993; Schlegel & Barry, 1991).

Let’s think about this. If teen turmoil were a biological imperative like puberty, wouldn’t we see it around the world, and wouldn’t we see it throughout human history?

In her classic book, Coming of Age in Samoa, anthropologist Margaret Mead was surprised by the almost complete lack of turmoil among the female teens in this small and primitive island paradise. With few exceptions, Mead wrote, the period of life we call adolescence “represented no period of crisis or stress, but was instead an orderly developing of a set of slowly maturing interests and activities. The girls’ minds were perplexed by no conflicts, troubled by no philosophical queries, beset by no remote ambitions” (Mead, 1928, p. 157). Mead’s study of Samoa was later criticized in some respects (Freeman, 1983), but more systematic anthropological studies later in the 1900s showed, among other things, that (a) in cultures in which teen turmoil had been completely absent – such as among the Inuit of northern Alaska – such turmoil emerged full-blown within 10 years of the introduction of Western media and education systems (Condon, 1990; Dasen, 2000), and (b) teen turmoil was absent in cultures worldwide in which children were integrated into adult society as soon as they showed signs of appropriate maturity and physical ability (Epstein, 2010; Graham, 2004; Huerre et al., 1990; Saraswathi, 2000), preserving what Jean Liedloff called the child-adult continuum (Liedloff, 1975).

Cameroon-based anthropologist, A. Bame Nsamenang, has asserted that the modern concept of adolescence exemplifies Eurocentric thinking – that is, of the practice of applying concepts that apply mainly to white Europeans to people worldwide (Nsamenang, 2002). In their summary study of the issue, co-authors Alice Schlegel (an anthropologist) and Herbert Barry III (a psychologist) concluded not only that Western-style adolescence was not universal but that it was absent in more than half of the preindustrial societies they studied. Speaking about such societies, the authors concluded, “Researchers have failed to find the Sturm und Drang that supposedly characterizes adolescence in Western society…” (Schlegel & Barry, 1991, p. 205). Most of these cultures, they said, didn’t even have a word for adolescence (p. 36).

History also has something to teach us on this issue. The Bible includes a story about some unruly boys who mocked the prophet Elisha (2 Kings 2:23–24), but that’s an exception; generally, the Bible portrays young people as competent and resourceful. The Old Testament includes a few minimum-age requirements, but the New Testament includes none at all. Young people in the Bible are often given great responsibility. Joash was given the full power to reign as king of the Israelites when he was seven, and he ruled for 40 years (2 Chronicles 24:1). Josiah became king of Judah at age eight and ruled for 31 years, always doing “what was right in the eyes of the Lord” (2 Kings 22:1–2). King David referred to the “sins of my youth” in Psalms 25:7 but he was referring to his own sins, not to a time of life when people are prone to sin. To this day, 7 is the “age of reason” under Catholic Canon Law (canon 97 §2). The Bible also has inspired young people to great feats. The Children’s Crusade of 1212 – thought by historians to have involved a group of 30,000 young people – was led by Stephen of Cloyes, a 12-year-old shepherd from France. The Catholic church honored many young people with sainthood – Jacinta Marto, age 9, Francisco Marto, age 10, Maria Goretti, age 11, Dominic Savio, age 14 (Graves, 2022; Wilson, 2020) – following Jesus’ teaching that great wisdom is often revealed to young children (Matthew 11:25).

No old cultures that we are aware of specifically mention a tumultuous time of life that looks like modern adolescence, even in literature where such a stage of life should be prominent. When Shakespeare listed the seven stages of life in As You Like It, the closest he got to adolescence was his third stage – “lover, Sighing furnace.” A tumultuous period of life like Western adolescence is completely absent in Hinduism, in which the “student stage” – Brahmacharya, which ends at about age 25 – progresses smoothly to the “householder stage” – Grihastha (Kakar, 1968; Oommen, 1992).

Historian Marc Kleijwegt of University of Wisconsin Madison wrote an entire treatise on this missing stage in ancient Greece and Rome, entitled, appropriately, Ancient Youth: The Ambiguity and the Absence of Adolescence in Greco-Roman Society. When young people were appointed to political offices in Greece and Rome, Kleijwegt said, they “were no longer regarded as children but as apprentice-adults” (Kleijwegt, 1991, p. 317)

The creation of adolescenceModern mainstream beliefs notwithstanding (Gross, 2015; Jensen & Nutt, 2015), the history of adolescence is actually relatively short, which contradicts the idea that adolescence is a necessary and universal period of life. The tumultuous period of life we currently associate with the teen years first appeared in post-Civil-War America (Ariès, 1962; Bettelheim, 1969; Epstein, 2010; Kleijwegt, 1991), when the industrial revolution brought the masses to the U.S. in large numbers (Klein, 2007).

As a result, the apprentice system – a system that had existed for perhaps thousands of years and that taught young people how to be adults – quickly collapsed, and young people who, in ages past, might have worked side-by-side with older family members on farms or in the trades, fled to the newly industrialized cities. They came from both rural America and countries throughout Europe and elsewhere, seeking their fortunes in the new factories (Klein, 2007). Tens of thousands of people – mainly unemployed young people – found themselves on the streets, often getting into trouble to feed themselves and their families (Klein, 2007; Stave, 1972).

In response to this new cultural turmoil, three entirely new social mechanisms were quickly invented to get young people under control. All three systems, it turns out, were developed and nurtured by Nobel laureate Jane Addams and her well-meaning, aristocratic associates at Hull-House in Chicago, Illinois (Addams, 1910; Epstein, 2010).

First, the juvenile justice system – a system that, ironically, stripped young offenders of their Constitutional rights – was used to sweep young people off the streets, often for engaging in behavior that had never been considered criminal before. In the early years of the juvenile court, more than half the delinquency cases were based on charges such as “immorality”, “vagrancy,” “truancy,” “disorderly behavior,” and “incorrigibility” (Platt, 1977, p. 140). Platt (1977) also cites a 1910 report by Harvey Baker of the Boston Juvenile Court indicating that relatively harmless activities such as playing ball on the street could result in sending young people to the newly created reform schools.

Second, “child labor laws” forbade most young people from doing any kind of work – another blow to the traditional apprentice system. And third, education was made mandatory throughout the U.S., and the minimum age through which young people had to remain in school was gradually increased over a period of years. The new mandatory education laws forced young people to attend school full-time whether they were ready to learn or not, and they had to attend even if they already knew the material. In other words, the new schools served largely as warehouses for the nation’s young (Epstein, 2010; Gatto, 2006). Ironically, the first child labor laws in the new American colonies encouraged children to work, in hopes of keeping young (and especially poor) children busy (Abbot, 1908; Cunningham, 1995), the logic being that “idle hands are the Devil’s tools” (Cunningham, 1995; Epstein, 2010, p. 37). For example, in 1640, the court of Massachusetts implemented a law requiring magistrates to see “what course may be taken for teaching the boys and girls in all towns the spinning of yarne [sic]” (Abbot, 1908, p. 16). Within the same year, the same court directed families to ensure that children and servants be “industriously implied [sic] so as the mornings and evenings and other seasons may not bee [sic] lost as formerly they have bene [sic]” (Abbot, 1908, p. 16). Also ironic, the first mandatory education law in early America – enacted in Massachusetts in 1852 – required young people to attend school until age 14, but only if they hadn’t already mastered basic skills, mainly “the three R’s”: reading, ‘riting, and ‘rithmetic (Epstein, 2010, p. 150; Katz, 1976). In other words, the first mandatory education law was competency-based, whereas the mandatory schooling laws that emerged in the early 1900s were simply age-based.

The introduction and convergence of these three systems – the juvenile justice system, the child labor laws, and the mandatory schooling laws – isolated young people from responsible adults, corralling them with large numbers of peers for the first time in human history.

These three systems institutionalized two cultural trends that are likely the main causes of the turmoil that led G. Stanley Hall and others to characterize the teen years (at least in the U.S. in the early 1900s) as a time of Sturm und Drang. The first trend is infantilization of young people, even when they are well past puberty, and the second is isolation of young people from responsible adults. These two trends, which increased in intensity and scope over the course of the 20th century, caused an increasingly large proportion of young people to become angry, defiant, or depressed.

An emphasis on cultural factors as the cause of teen turmoil is not new. We mentioned Margaret Mead’s book earlier. Also notable are arguments proposed by philosopher Ivan Illich (1971), home schooling proponent John Holt (1974), and psychologist Richard Farson (1974). As psychologists L. Joseph Stone and Joseph Church put it in their 1957 book, Childhood and Adolescence, “The psychological events of adolescence in our society are not a necessary counterpart of the physical changes of puberty, but a cultural invention – not a deliberate one, of course, but a product of an increased delay in the assumption of adult responsibilities” (Stone & Church, 1957, p. 271–272).

An ecological approachIn recent years, experts on teens have also applied principles from the field of ecology to the teen problem, and some have proposed that this perspective should be included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the diagnostic manual used by most Western clinicians. Both the DSM-5, released in 2013 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), and its European counterpart, the ICD-11, published in 2019 (World Health Organization, 2019/2021), include both biological and cultural factors in the diagnostic categories most commonly applied to teens, with biological factors playing an especially important role (see Table S1 in Supplementary Materials). If biological factors actually play only a small role, if any, in teen turmoil, what is the alternative? One option is to use concepts and models from ecology (Brymer & Schweitzer, 2022; Dulcan, 2010; Ysseldyke et al., 2012; cf. Flaskerud, 2010; Scotti et al., 1996).

Ecology is the study of organisms and their interaction with each other and the environment (Molles & Sher, 2022; cf. Heft, 2013; Lobo et al., 2018). The ecological school of psychology was developed in the mid-1900s by Kurt Lewin, James Gibson, Urie Bronfenbrenner, and others as a response to classical behaviorism (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Heft, 2022; Lobo et al., 2018). An ecological approach to understanding teen turmoil overlaps with the cultural perspective we have outlined above in some key respects. Both look carefully at environmental factors, but the cultural approach is relatively simplistic: It takes note of changes in behavior (and, often, in emotions) that follow cultural change – the emergence of adolescence set in motion by the Industrial Revolution, for example – but it overlooks the dynamics of change. When the apprentice system gave way to factory labor, for example, young people were not only affected, they also influenced the way factories developed. Because employers could pay children and teens far less than they paid adults, it became common in some industries to fire the dad and hire the child (Beulah, 1937) – a practice that disrupted families and strengthened unions (Lumpkin & Douglas, 1937). Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) Ecological Systems Theory not only anticipated such dynamics, it recognized that such dynamics were fundamental to social systems, including the systems that created adolescence.

According to Bronfenbrenner, “The ecology of human development involves the scientific study of the progressive, mutual accommodation between an active, growing human being and the changing properties of the immediate settings in which the developing person lives, as this process is affected by relations between these settings, and by larger contexts in which the settings are embedded” (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, p. 21). Ecological models applied to mental health issues recognize the dynamics, the complexities, and the interactions in which human behavior and emotion are embedded in every society; they thus provide an especially sophisticated framework for understanding emerging trends in mental health and in developing appropriate interventions (Eriksson et al., 2018).

Note that from this perspective, teen problems aren’t caused by environmental factors; rather they emerge from an interaction between changing characteristics of teens and changing characteristics of the social environment. For ecological psychologists, “the organism-environment system [is the] unit of analysis” (Lobo et al., 2018, p. 1). That emphasis on interaction sets the ecological perspective apart from other analytical perspectives in psychology. This perspective has implications not only for understanding complex phenomena in psychology but also for clinical diagnosis and treatment (Brymer & Schweitzer, 2022).

Both individual scholars and study groups looking at child and adolescent problems in preparation for updating the DSM IV, published in 1994, to version 5, ultimately published in 2013, had called for reassessing such problems using ecological principles. T. B. Gutkin, for example, called for “abandoning the medical model” normally used to characterize the problems of children and teens; “a paradigm shift toward an ecological model is both essential and long overdue,” (Gutkin, 2012; cf. Robles et al., 2014). Dulcan’s Textbook of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, published in 2010, mentioned a 1999 DSM-5 planning conference in which concerns were raised about assuring that the new DSM included “how to assess impairment [and] the effects of the multiple interactions between the child and the child’s environment (an ecological model) [sic].” Unfortunately, these concerns and suggestions never made their way into the DSM-5, which continues to use the traditional medical model (Epstein, 2013; Greenberg, 2013).

Present studyIt can reasonably be argued, we believe, that there is a need to develop one or more DSM-type diagnostic categories of teen turmoil that eschew the medical model and that employ concepts from ecological psychology and the cultural and historical analysis of teen problems we have summarized above. In that spirit, we have previously proposed that existing diagnostic categories for some teen problems, such as major depression, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder, do not do justice to the social causes of those problems (Epstein, 2007, 2010, 2015). As an alternative, we have suggested the possible utility of a diagnostic category called “extended childhood disorder” (ECD; Epstein et al., 2011) which is characterized by three features: (1) excessive and sometimes harmful involvement with peers, (2) conflict centering around control issues with parents or other authority figures, and (3) mood problems centering around control issues with parents or other authority figures. The present study uses an online sample of >5000 people to evaluate the possible validity of a new diagnostic instrument – the Extended Childhood Disorder Inventory (ECDI) – that could be used to diagnose ECD.

In the present study, we evaluate a 20-item questionnaire designed to diagnose ECD. The questionnaire looks at three interactions between teens and their social environment that might account for most of the problems we see in teens in Western countries. The validity of the new questionnaire is evaluated using a “concurrent study” design. Its main purpose is to see how well test scores can predict a variety of self-reported criterion variables that are generally associated with behavioral, emotional, and substance abuse disorders.

MethodsEthics statementThe federally registered Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the sponsoring institution (American Institute for Behavioral Research and Technology) approved this study (protocol number 1102) with exempt status and a waiver of the requirement for informed consent under the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) regulations (45 CFR 46.116(d), 45 CFR 46.117(c)(2), and 45 CFR 46.111) because (a) the anonymity of participants was preserved and (b) the risk to participants was minimal. The IRB is registered with the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) under number IRB00009303, and the Federalwide Assurance number for the IRB is FWA00021545.

Study designOur investigation employed a “concurrent study design” that provided convergent validity evidence with related measures. This research design is described in the most recent edition of Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing, jointly published by the American Educational Research Association (AERA), the American Psychological Association, and the National Council on Measurement in Education (American Educational Research Association, 2014). Specifically, we sought to measure the strength of the relationships between our questionnaire scores and the scores on 13 criterion questions. This design is called “concurrent” because we obtained test scores and criterion measures at the same time, a strategy that avoids possible temporal confounds.

Test developmentTwo versions of the ECDI were first posted online at https://ExtendedChildhoodDisorder.com in September 2010. The first version, the ECDI-s, allowed users to evaluate themselves; the second version, the ECDI-o, allowed people (typically parents or mental health professionals) to evaluate someone else.

As noted above, ECD is characterized by three features: (1) excessive and sometimes harmful involvement with peers, (2) conflict centering around control issues with parents or other authority figures, and (3) mood problems centering around control issues with parents or other authority figures. Table 1 shows, for each of these three areas, the items from the ECDI-o version of the questionnaire that are included in that area, along with references we used to help us develop each area. Table 1 also includes newer references (from 2010 or later) that we believe are relevant to the original questionnaire.

Three Criteria for the Possible Diagnosis of Extended Childhood Disorder Inventory (ECDI-o).

1. Peer Involvement (4 items): Excessive and sometimes harmful involvement with peers.

|

| References:Condon, 1990; Csikszentmihalyi & Schneider, 2000; Lam et al., 2014; Mercer et al., 2016; Schlegel & Barry, 1991; Updegraff et al., 2006 |

2. Conflict (8 items): Conflict centering around control issues with parents or other authority figures.

|

| References:Barber et al., 1994; Barnes & Farrell, 1992; Curtner-Smith & MacKinnon-Lewis, 1994; Pettit et al., 2001; Rodríguez-Meirinhos et al., 2019 |

3. Mood (8 items): Mood problems centering around control issues with parents or other authority figures.

|

| References:Barber et al., 1994; Gómez-Ortiz et al., 2019; Gray et al., 2023; Pettit et al., 2001; Qin et al., 2009; Rodríguez-Meirinhos et al., 2019; Soenens et al., 2008 |

Note. The ECDI-o is the version completed by therapists, counselors, school officials, parents, or others who are evaluating another person. Another version of the test – the ECDI-s – is designed for self-evaluation and has different instructions and first-person versions of the test items (see Figure S1 in the Supplementary Materials). Table 1 includes some references that post-date the creation of the EDTA. As explained at the end of the Methods section, ECD was said to be “present” when at least one item had been selected in the “excessive peer involvement” category and at least two items had been selected in each of the other two categories (mood issues and conflict issues). ECD was otherwise said to be “absent.”

For each of the three criteria, here is a summary of how we used relevant literature to formulate inventory items.

Excessive and sometimes harmful involvement with peersU.S. teens spend significantly more time with peers than teens do in other industrialized nations (Csikszentmihalyi & Schneider, 2000), and teens in industrialized nations spend far less time with adults than teens do in preindustrial nations, where they often work side-by-side with adults learning to become adults (Schlegel & Barry, 1991). Spending almost all their time with peers puts teens at risk. According to Csikszentmihalyi and Schneider (2000): “When they are with peers, teenagers feel significantly happier but are also less able to concentrate and are less in control of their actions. It is the hedonistic values of the peer culture that are transmitted in such contexts, rather than more realistic prerequisites for a productive adulthood.” In a study of 186 preindustrial societies, the authors found that antisocial behavior among teens was most common in the few societies in which teens spent most of their time with peers (Schlegel & Barry, 1991). In a longitudinal study of the Inuit Indians of Canada conducted over a period of years (1978 to 1988) when the Inuit were rapidly becoming Westernized, researchers documented a rapid increase in problem behaviors among teens, including “alcohol abuse, spousal assault, vandalism, and increasing conflict” (Condon, 1990, p. 275). They also noted an increase in the prevalence of large adolescent peer groups. The increase in teen problems was so severe that it forced the Inuit to create the first police department they ever had – a permanent detachment of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. These and other sources helped us to develop Item 8 (“He or she is in contact with peers during most waking hours through face-to-face contact or electronic communication”), Item 19 (“He or she is very dependent on and involved with peers….”), and similar items.

Conflict centering around control issues with parents or other authority figuresIn a study of 473 fifth, eighth and tenth graders from Knox County, Tennessee, the level of parental behavioral control was positively correlated with the externalized problems of their teenage offspring (no causal inference is intended here) (Barber et al., 1994). Studies of this sort helped us to create Item 10 (“He or she sometimes engages in risky behavior often seen as inappropriate for young people…, such as sexual behavior, smoking, gambling, or drinking”) and Item 17 (“He or she gets into trouble at school at least once a month, or has been suspended or expelled from school within the past year”).

Similarly, in a study of 440 mothers and their 13-year-old children who participated in the “Child Development Project” in Indiana and Tennessee (U.S.), mothers’ use of controlling parenting methods was associated with delinquent behavior problems among their offspring (Pettit et al., 2001). Studies like this helped us to create Item 7 (“He or she has little respect for rules or laws and may have broken the law within the past six months….”), Item 12 (“Within the past year, he or she has been violent, planned violence, or possessed or used weapons”), and similar items.

Mood problems centering around control issues with parents or other authority figuresThe Pettit et al. (2001) study also found that control by parents was associated with increases in anxiety and depression in their teens, and the Barber et al. (1994) study was predictive of internalized problems, not just externalized ones (cf. Soenens et al., 2008). These studies helped us to create Item 14 (“Within the past year, he or she has had thoughts of committing suicide, has spoken of committing suicide, has planned suicide, or has attempted suicide”), Item 13 (“He or she has a poor self-image or low self-esteem, is very self-conscious, or is overly concerned about his or her image, weight, or body type”), Item 3 (“Within the past six months, he or she has been depressed for a period of at least two weeks with no apparent cause”), and Item 16 (“Over the past six months, and for a period lasting at least two weeks, he or she has felt lonely, has felt awkward or anxious around other people, or has withdrawn from other people”).

ParticipantsBecause of the way this study was designed, we need to introduce some simple language to distinguish between three groups of people: (a) Self-evaluated participants. These were the 4690 people who completed the ECDI-s version of the questionnaire in order to evaluate themselves. (b) Other-evaluated participants. These were the 508 participants who were evaluated by others using the ECDI-o version of the questionnaire. (c) Evaluators. These were the 508 people – parents, counselors, and others – who completed the questionnaire in order to evaluate someone else. A total of 5198 individuals were evaluated in the study. 54.3 % of the participants were from the U.S., and the remaining 46.7 % were from 74 other countries (Table 2).

Demographic Information (ECDI-s and ECDI-o).

| Variable | n (%) | Mean Peer Involvement Score (SD)† | Mean Mood Score (SD)† | Mean Conflict Score (SD)† | Mean Total Score (SD)† | Significance Test | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||||

| (Mean = 23.4, | |||||||

| Median = 20.0) | |||||||

| 15-20 | 2693 (51.8) | 1.4 (1.1) | 5.3 (2.2) | 2.1 (1.8) | 8.7 (3.8) | t = 17.0 | < .001 |

| 21-88 | 2503 (48.2) | 0.8 (1.0) | 4.4 (2.3) | 1.8 (1.7) | 6.9 (3.7) | ||

| Missing Values | 2 (0.04) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 3147 (60.5) | 1.1 (1.1) | 5.1 (2.2) | 1.9 (1.7) | 8.1 (3.9) | F = 44.4 | < .001 |

| Male | 1750 (33.7) | 0.9 (1.0) | 4.3 (2.3) | 2.0 (1.8) | 7.2 (3.9) | ||

| Other | 301 (5.8) | 1.4 (1.2) | 5.7 (2.1) | 1.9 (1.7) | 9.0 (3.6) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 3614 (69.5) | 1.0 (1.1) | 4.8 (2.3) | 1.9 (1.8) | 7.8 (3.9) | F = 1.7 | .16 NS |

| Black | 261 (5.0) | 1.1 (1.1) | 4.5 (2.3) | 1.7 (1.6) | 7.3 (3.9) | ||

| Hispanic | 341 (6.6) | 1.2 (1.1) | 4.9 (2.3) | 2.0 (1.7) | 8.1 (3.9) | ||

| Asian | 514 (9.9) | 1.1 (1.1) | 5.0 (2.3) | 1.8 (1.5) | 7.9 (3.6) | ||

| Other | 394 (7.6) | 1.0 (1.1) | 5.0 (2.2) | 1.9 (1.8) | 7.9 (3.9) | ||

| Missing Values | 26 (0.5) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Level of Education | |||||||

| None | 1004 (19.3) | 1.5 (1.2) | 5.3 (2.2) | 2.2 (1.9) | 9.0 (4.0) | F = 77.0 | < .001 |

| High School | 2262 (43.5) | 1.2 (1.1) | 5.1 (2.2) | 2.1 (1.7) | 8.3 (3.7) | ||

| Associates | 319 (6.1) | 0.9 (1.0) | 4.5 (2.2) | 1.9 (1.7) | 7.4 (3.9) | ||

| Bachelor’s | 1166 (22.4) | 0.8 (1.0) | 4.3 (2.3) | 1.6 (1.5) | 6.7 (3.6) | ||

| Master’s | 348 (6.7) | 0.6 (0.9) | 3.9 (2.3) | 1.3 (1.5) | 5.8 (3.6) | ||

| Doctorate | 72 (1.4) | 0.4 (0.7) | 3.2 (2.4) | 1.4 (1.4) | 4.9 (3.8) | ||

| Missing Values | 27 (0.5) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Sexual Orientation | |||||||

| Straight | 2622 (50.4) | 0.9 (1.0) | 4.3 (2.3) | 1.8 (1.7) | 7.0 (3.8) | F = 68.2 | < .001 |

| Bisexual | 951 (18.3) | 1.3 (1.2) | 5.1 (2.3) | 2.0 (1.7) | 8.4 (4.0) | ||

| Gay or Lesbian | 409 (7.9) | 1.3 (1.7) | 5.5 (2.1) | 2.3 (1.8) | 9.1 (3.9) | ||

| Other | 361 (6.9) | 1.2 (1.2) | 5.4 (2.1) | 1.8 (1.7) | 8.4 (3.6) | ||

| Unsure | 755 (14.5) | 1.2 (1.1) | 5.5 (2.0) | 1.9 (1.6) | 8.5 (3.5) | ||

| Missing Values | 100 (1.9) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Straight | 2622 (50.4) | 0.87 (1.0) | 4.3 (2.3) | 1.8 (1.7) | 7.0 (3.8) | t = 15.8 | < .001 |

| Non-Straight | 2576 (49.6) | 1.25 (1.2) | 5.4 (2.1) | 2.0 (1.8) | 8.7 (3.8) | ||

| Country of Origin | |||||||

| United States | 2822 (54.3) | 1.1 (1.1) | 4.7 (2.3) | 2.0 (1.8) | 7.8 (4.0) | t = -1.2 | .25 NS |

| Other | 2376 (45.7) | 1.0 (1.1) | 5.0 (2.3) | 1.9 (1.7) | 7.9 (3.8) |

Note. Significance tests and p values compare mean total scores.

Data were cleaned as follows: Cases were removed if English fluency was <6 on a scale from 1 to 10 where 1 was labeled “Not very fluent” and 10 was labeled “Highly fluent.” Following guidelines from the sponsoring institution’s IRB, because the Flesch-Kincaid reading level of the questionnaire was 9.9, we removed all cases in which the age was under 15; in the U.S., students are typically age 15 or older when, on average, they have a reading level of 9.9 or greater (K12academics, n.d.; Kincaid et al., 1975). We also removed cases in which individuals completed the questionnaire more than once on the same day; in such cases, we retained only the first set of results for which all demographic questions were completed.

Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics of the 5198 people who were evaluated in the study, either by others or by themselves. Tables S2 and S3 show these characteristics broken down by people who were evaluated by others and by people who evaluated themselves, respectively.

The sample should be considered a convenience sample because after the questionnaire was posted online (see below), we made no attempts to recruit people to complete it. The present study includes individuals who took the tests between September 16, 2010, and August 17, 2023.

Evaluators reported their reasons for completing the questionnaire as follows: 448 (88.2 %) said personal concern; 13 (2.6 %) said clinical evaluation; 12 (2.4 %) said student evaluation; 3 (0.6 %) said court evaluation; 27 (5.3 %) said other reason, and the remaining 5 (1.0 %) did not specify a reason. The professions of the evaluators were as follows: 80 (15.7 %) identified themselves as teachers, 22 (4.3 %) as other medical practitioners, 20 (3.9 %) as nurses, 20 (3.9 %) as social workers, 19 (3.7 %) as youth workers, 18 (3.5 %) as counselors, 14 (2.8 %) as psychologists, 11 (2.2 %) as members of the clergy, 8 (1.6 %) as coaches, 7 (1.4 %) as human resource professionals, 6 (1.2 %) as school administrators, 5 (1.0 %) as attorneys, 2 (0.4 %) as physicians, 1 (0.2 %) as a court officer, 1 (0.2 %) as a psychiatrist, 1 (0.2 %) as a school counselor, and 244 (48 %) as “other,” with the remaining 29 (5.7 %) not specifying a profession. Those evaluating another person described their relationship to that person as follows: 211 (41.5 %) as parents, 90 (17.7 %) as other relatives, 73 (14.4 %) as friends, 57 (11.2 %) as spouses, 10 (2.0 %) as therapists, 6 (1.2 %) as teachers, 5 (1.0 %) as counselors, and 48 (0.9 %) as others, with 8 (1.6 %) not specifying a relationship.

For people being evaluated by others, the mean age was 24.2 years (SD = 10.6; median = 20.0). For people evaluating themselves, the mean age was 23.3 years (SD = 9.0; median = 20.0) (t = 2.0, p = .04). For additional demographic differences between these two groups see Tables S2 to S4 in the Supplementary Materials.

ProcedureBefore being shown the actual test items, test takers were asked a number of demographic and criterion questions, including questions about personal happiness, anger, depression, and anxiety. As noted above, the test itself, accessible on the internet at https://ExtendedChildhoodDisorder.com, contains 20 questions in three categories, as follows: four questions regarding excessive involvement with peers, eight questions regarding conflict issues, and eight questions regarding mood issues (Table 1). Test takers were given some general background information about the concept and then advised that “the present test is being used for research purposes” and “should not be used to make clinical diagnoses.”

In the ECDI-o, test items were stated in third-person format (Table 1); in the ECDI-s, test items were stated in first-person format (Figure S1). For each version, test takers were advised to click on items that they felt were true for the person being evaluated. Results were reported immediately when the test taker clicked on a “submit” button. Extended childhood disorder was said to be “present” when at least one item had been selected in the “excessive peer involvement” category and at least two items had been selected in each of the other two categories (mood issues and conflict issues). Extended childhood disorder was otherwise said to be “absent.” The criteria for assigning the present or absent label were then explained, and the test items that had been selected in each of the three categories were displayed.

Note that because the questionnaire contains four items in the peer category and eight items in each of the other two categories, the scoring is not weighted to favor one category over another. We believe that it would be inappropriate in the early stages of development of a new diagnostic classification for us to weight the scores in the absence of relevant empirical evidence. The number of items in each category was constrained by the empirical literature from which the items were derived (see Section Test development and Table 1 above).

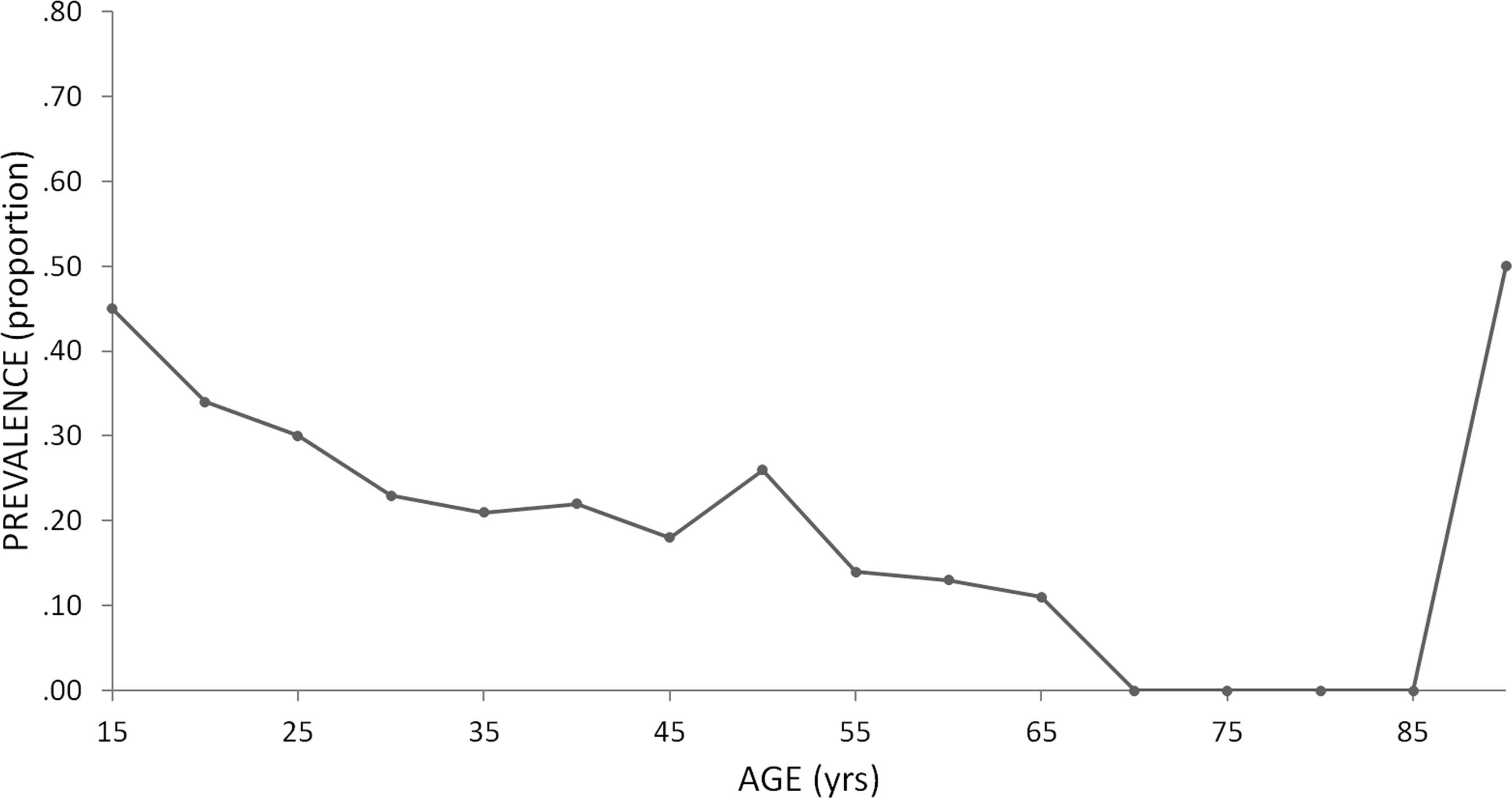

ResultsClinical validityThe results generally supported the clinical validity of the extended childhood disorder concept. As predicted, total scores on the test (that is, the total number of test items selected) decreased with both age (r = −0.27, p < .001) and educational level (r = −0.26, p < .001). They were also negatively correlated with level of happiness (r = −0.39, p < .001), whether reported by the individual him- or herself (r = −0.39, p < .001) or by another person (r = −0.35, p < .001). Again, as predicted, test scores were positively correlated with anger (r = 0.34, p < .001), depression (r = 0.44, p < .001), and anxiety (r = 0.41, p < .001), whether reported by self or others. In addition, the prevalence of the disorder, as indicated by the proportion of “present” outcomes, was higher at younger ages (r = −0.17, p < .001; Fig. 1), and the mean proportion of items selected from the mood category was significantly greater than the mean proportion of items selected from the peer and conflict categories combined (z = 10.3, p < .001; Fig. 2).

For both groups combined (n = 5198), total scores were also good predictors of whether participants had ever been hospitalized (Myes = 9.7 [SD = 3.9], Mno = 7.5 [SD = 3.8], t = −14.7, p < .001), whether they had ever been diagnosed with a mental disorder (Myes = 8.6 [3.9], Mno = 7.3 [3.7], t = −12.6, p < .001), whether they had ever been on medication (Myes = 8.5 [3.9], Mno = 7.4 [3.8], t = −9.9, p < .001), whether they were currently on medication (Myes = 8.6 [3.7], Mno = 7.6 [3.9], t = −8.2, p < .001), whether they had ever been in therapy (Myes = 8.3 [3.9], Mno = 7.2 [3.7], t = −10.1, p < .001), whether they were currently in therapy (Myes = 8.8 [3.8], Mno = 7.6 [3.8], t = −10.0, p < .001), whether they had ever been arrested (Myes = 9.1 [4.3], Mno = 7.7 [3.8], t = −7.4, p < .001), whether they were currently employed (ages 16 and over only) (Mno = 8.4 [3.7], Myes = 7.0 [3.9], t = 11.5, p < .001), and whether they were currently married [ages 18 and over] (Mno = 7.7 [3.8], Myes = 5.7 [3.8], t = 10.3, p < .001).

Demographic effectsWe have summarized demographic effects in Table 2. Again, for both groups combined (n = 5198), we found an effect for sexual orientation, with those identifying as non-straight scoring significantly higher than those identifying as straight. We also found significant effects for gender, education, and parenthood. We found no significant effect for race/ethnicity. Nor did we find significant differences between the scores of people in the U.S. and people in other countries. Our sample did not have enough participants in individual countries outside the U.S. for us to conduct a country-by-country analysis.

Regression and factor analysisA single-component regression analysis showed that the mood component of the test was the best predictor of three of our four criterion variables (happiness, anxiety, and depression) and that the conflict component was the best predictor of anger (Table 3). For multicomponent regression analyses, see Table S5 in the Supplementary Materials. An exploratory factor analysis yielded three components that can be reasonably called “mood problems,” “risky/rebellious behavior,” and “need for social validation” (Table 4). The factors clustered roughly in a manner consistent with our three scales: “mood issues,” “conflict issues,” and “excessive peer involvement” respectively.

Single-component regression results showing how well scores on the three scales of the ECDI predicted answers to our four criterion questions.

Note. Results are shown for one-component models in stepwise regressions, one for each of the four criterion variables. *** p < .001.

Exploratory Factor Analysis for the 20 Items.

Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis.

Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization.

Note. Values <0.3 are omitted.

The results of this study generally support the validity of the extended childhood disorder concept, although the study should be considered exploratory. It is notable, for example, that the prevalence of ECD in the present sample (45.8 %, ages 15 to 18) roughly matches the most recent National Comorbidity Survey estimate (49.5 %), using DSM-IV criteria, of the prevalence of teen disorders in the U.S. (Merikangas et al., 2010). It is also notable that ECDI test scores were significantly predictive of 13 self-reported criterion variables, among them clinically important variables such as hospitalization for mental health related problems, history of therapy, history of psychoactive medication, and levels of happiness, anger, depression, and anxiety. As one might expect, total scores on the ECDI were also significantly negatively correlated with age. In addition, the prevalence of the disorder, as indicated by the proportion of “present” outcomes, was higher at younger ages (Fig. 1).

Limitations and future researchFor a diagnostic category to be adopted, it should have value in treatment, as well as widely accepted theoretical foundations. Extended childhood disorder satisfies neither of these criteria. What’s more, if Epstein (2010), Graham (2004), and others are correct about the social origins of most teen problems, the idea of further pathologizing such problems with yet another diagnostic label should be questioned. On the positive side, the proposed diagnostic category, by its very name and nature, calls attention to a central cause of the disorder: namely, that we tend to infantilize our young people long after they have passed puberty, as well as to isolate them from responsible adults (Epstein, 2010; cf. Csikszentmihalyi & Schneider, 2000; Epstein et al., 2024; Liedloff, 1975).

Also notable is that the components that emerged in our exploratory factor analysis were roughly consistent with the three empirically-based criteria (peer involvement, mood issues, and conflict) that were central to the ECDI. Note that we did not perform a confirmatory factor analysis. Following guidelines from Izquierdo et al. (2014), we believe that a confirmatory factor analysis should ideally be conducted with a new sample of participants in a future study.

Another finding of note in our study is that of the three criteria that were used to determine whether ECD was present or absent, “mood problems centering around control issues with authority figures” proved to be substantially more problematic and predictive than the other two criteria (“excessive and sometimes harmful involvement with peers” and “conflict centering around control issues with authority figures”). This was not an outcome we had anticipated, and it should be explored further. Mood problems are common among young people, at least in Western countries (see Table 1 and Epstein, 2010), but why prevalence in this criterion category was so much higher than prevalence in the other two categories is not clear.

We also acknowledge a limitation to the simple method of scoring we chose to use in this study. As we noted earlier, the ECDI reports that the disorder is “present” if a participant selects at least one item in the peer category and at least two items in each of the other two categories (mood and conflict). Ideally, future research will allow us to weight these categories using rational, data-based criteria. One could say the same about roughly 300 disorders listed in the DSM-5, of course. Unfortunately, hard data are used in making decisions about DSM-5 content far less frequently than one might think. This applies to determining whether a diagnostic category is added to or removed from the manual, which diagnostic criteria are listed for a diagnosis, and the order in which those criteria are listed (Greenberg, 2013; cf. Epstein, 2013). DSM diagnostic categories are decided by “consensus panels,” often operating in secret and sometimes deliberating without the guidance of empirical data (Frances & Widiger, 2012; Kendler & Solomon, 2016). This should not, in our view, discourage scholars and scientists – particularly those who are interested in how the mental health professions view and treat young people – from offering diagnostic guidance that is culturally, historically, and empirically grounded.

This particular study is also limited by the source of our sample: namely, the internet. This source gave us no control over the makeup of the sample. On the positive side, it also gave us a large and diverse set of 5198 participants from the U.S. and 74 other countries. As we noted earlier, because we had only small numbers of participants from most of these countries, we could not conduct a meaningful multicultural analysis of our data; that is a matter for future research. The relatively strong and consistent statistical results we found notwithstanding, further study is needed regarding this proposed disorder.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.