Myiasis includes several entities recognized in the rural environment. It occurs generally in older adults and may compromise locations from the skin and scalp to mucous membranes. The responsibles are insects of the Diptera class, whose larvae develop in living tissues thus infesting of the host. We report the case of an 82-year-old patient with a furuncular right knee lesion associated with Dermatobia hominis myiasis. Following the extraction, full recovery was achieved after a 3-week follow-up. An eco-epidemiological study of the patient's environment revealed all factors that favor the development of myiasis.

Las miasis son entidades reconocidas en el ambiente rural, se presentan generalmente en adultos mayores y pueden comprometer desde piel y cuero cabelludo hasta mucosas. Los responsables son insectos de la clase díptera cuyas larvas se desarrollan en los tejidos vivos del hospedero que infestan. Se presenta el caso de una paciente de 82 años con lesión foruncular en rodilla derecha asociada a miasis por Dermatobia hominis. Posteriormente a la extracción hubo recuperación total después de 3 semanas de seguimiento. Se realizó un estudio ecoepidemiológico del entorno de vida de la paciente, encontrando todos los factores ambientales que favorecen el desarrollo de las miasis.

Myiasis, caused by Dermatobia hominis (Linnaeus, 1781) (Díptera: Calliphoridae) commonly known as flystrike or blowfly strike, or maggot infestation (“nuche” in Spanish), is one of the infestations that greatly impacts economically important animal populations such as cattle, horses and other species.1

Dermatobia belongs to the class Diptera and family Oestridae; it has a life cycle of indirect infestation by “phoresis”, that consist in the transfert of eggs to a host animal via other blood sucking insects of the genus Aedes (Linnaeus, 1761), Psorophora (Robineau desvoidy, 1827), Stomoxys (Linnaeus, 1758), house flies and ticks. The result of this process is the invasion of living tissue by larvae which is called specific myiasis.1–3

The specific type of injury that generates infestation by D. hominis through single or multiple inoculations is furunculous in nature due to the inflammatory reaction, mechanical and enzymatic damage caused by larvae.2–6

Human population susceptible to accidentally infestation corresponds to inhabitants or migrants to tropical or subtropical areas below 1400m above sea level and in areas with moist soils; because of the life cycle of insects, fly population commonly increases in the month after the rainy season.3

The primary treatment consists of removal of larvae by suffocation or through surgical incision. In the first case, it is done using Vaseline, grease or other item that plugs the breathing hole of the larva which is forced to move to the outside. In the surgical procedure, a small incision is made and then the larva is removed with tweezers. In most cases, the use of topical antibiotic to reduce the risk of superinfection is recommended.3–6

Other common myiasis-causing agents in our environment are Cochliomyia spp. (Coquerel, 1858) and Lucilla spp. (Pilsbry, 1890).7–10 This paper presents a clinical case of D. hominis myiasis and its eco-epidemiological related aspects.

Clinical caseAn 82-year-old female with a history of hypothyroidism, hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus, therapeutically controlled with sodium levothyroxine 50mg 1h before breakfast, glyburide 5mg at breakfast and dinner, acetylsalicylic acid 100mg after lunch, metformin 850mg, metoprolol 50mg, losartan 100mg, ciprofloxacin 500mg every 12h, gemfibrozil 600mg, furosemide 40mg, omeprazole 20mg, calcium carbonate 500–600mg plus vitamin D3 200IU tablet every day, clonidine 150mg and acetaminophen 500mg every 8h. The patient originated of the village of Chinauta, municipality of Fusagasugá−Cundinamarca, Colombia. She consulted to School of Medicine, at Universidad Militar de Bogotá presenting a right knee lesion of a month of evolution, characterized as a furunculous and erythematous lesion with a central hole and inflammation that surrounded the area. When applying pressure on the lesion, the presence of purulent exudate was noticed (Fig. 1A) and it was associated with occasional stabbing pain. All procedures were performed after signature of the informed consent.

The patient was in good general conditions, alert and aware. Blood pressure 150/80mmHg, pulse 68 beats per minute, axillary temperature 36.8°C. A week before the patient had consulted to her Healthcare Institution—IPS—in Fusagasugá for the same reason; she was prescribed topical treatment with 2% fusidic acid and oral therapy with dicloxacillin 500mg. The patient reported having taken dicloxacillin for 4 days and discontinued its use because of fever, vomiting, headache, generalized edema, itching and rash.

The patient reported that the larva was removed and delivered to the authors who proceeded to preliminary identification in the microbiology laboratory. Subsequently, the specimen was categorized as a stage 1 larva (8mm) of D. hominis (Fig. 2) in the Microbiology and Parasitology Research Center at Universidad de los Andes−Bogotá.

The patient continued with outpatient management during two weeks with topical 2% fusidic acid; last control was made at home (Chinauta, Cundinamarca) with no evidence of other larvae in or around the initial lesion and a good tissue recovery (Fig. 1B and C).

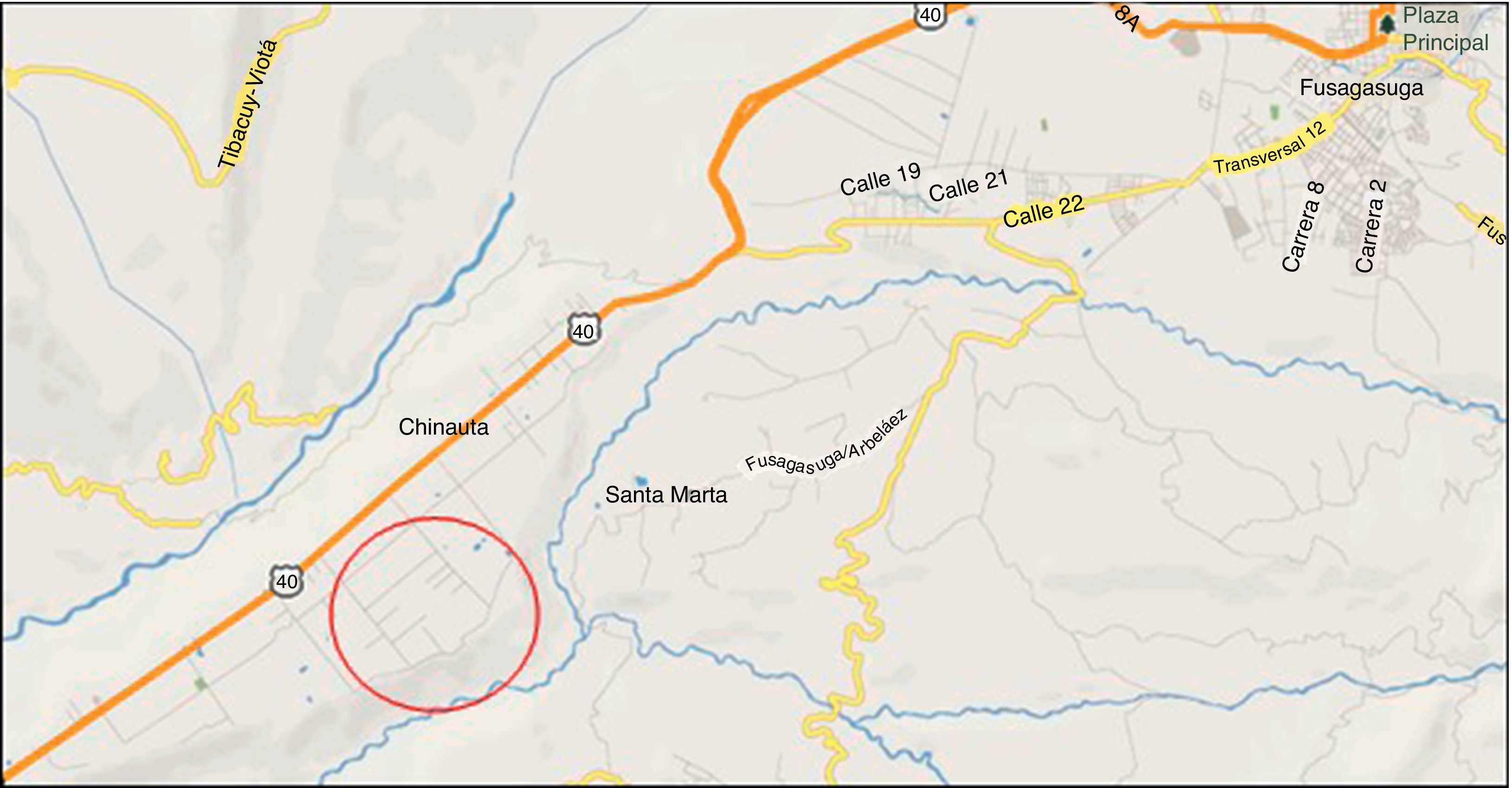

The eco-epidemiological study11 was performed in Chinauta, a southwest village of the province of Fusagasugá, Cundinamarca Department, Colombia. Chinauta is located 70km from Bogotá D.C. (capital city), 1h and 30min by R40 highway (Fig. 3). It is over 1200mamsl near to a major river named Cuja, with an estimated population of 5000 habitants; tourism is the principal economic activity; there are many relaxing places with swimming pools and night accommodations.

Although during our field visit no wild mammal species were found, the presence of armadillos (Dasypus), foxes (Cerdocyon), rabbits, rats (Rattus), bats, opossum (Virginia) (‘faras’ in Spanish), nocturnal monkeys, among others has been reported. Regarding the birds, commonly found species are swallows, owls, vultures, harrier hawks, doves (Columba), blackbirds (Turdus), ‘chirlobirlos’, cardinal tile (Cardinalis), ‘pechiamarillo’ (Capsiempis), ‘copetón’ (Zonotrichia), parrots (Amazona), hummingbirds (Topaza), canaries, wrens, hawks (Accipiter), macaws (Ara), among others. The most representative reptiles are snakes such as the hunter (Dendrophidion), coral, false coral, four noses (Bothrops), rattle (Crotalus) and size Xs (Bothrops asper), and some species of lizards, chameleons and iguanas. Within amphibians, there are arboreal and terrestrial frogs and particularly the bullfrog. The fish fauna is represented by silver sardines, doghouse, ‘tilapia’ (Oreochromis) and trout.12

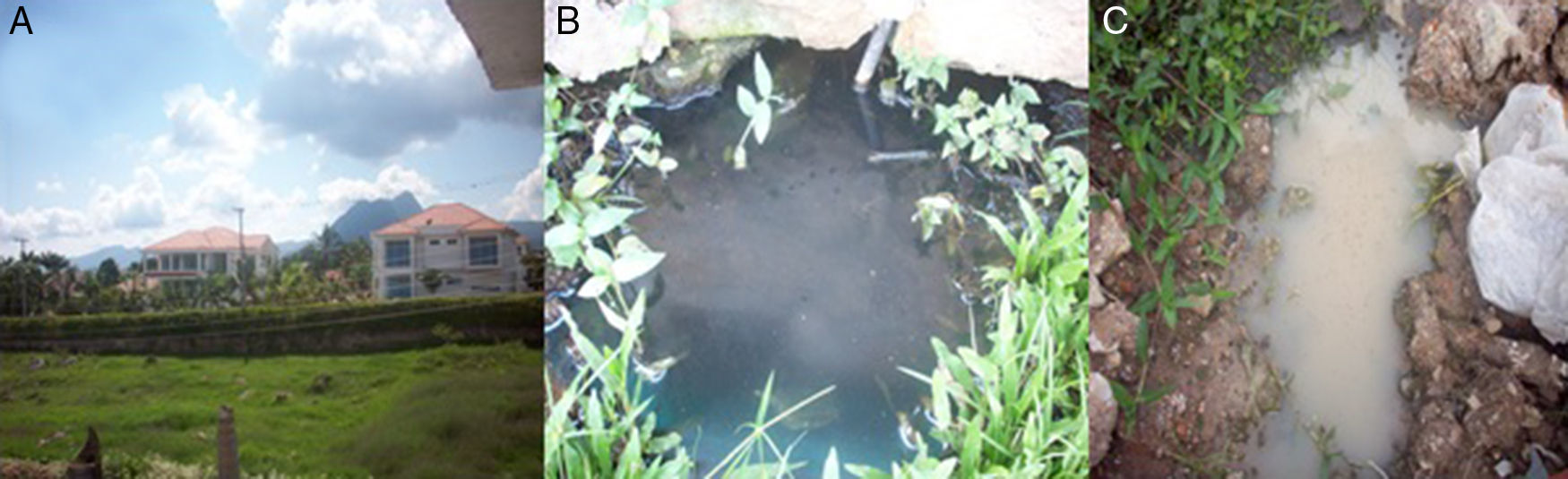

During field work the temperature ranged between 23°C and 28°C in a sunny day. Houses are made of blocks and concrete with two or three floors (Fig. 4A), many of them with swimming pools.

The houses in the village have drinking water although most have not sewage. Chinauta is an important relaxation place for people who live in the capital city; many houses are rented for vacations; there are drug abuse rehabilitation centers, geriatric homes, and cultivation of ornamental flowers as well.

DiscussionIt has been documented that the main groups at risk for human myiasis are composed by indigent, weak or elderly people, such as our patient.1 Likewise, different diseases are predisposing factors for myiasis, such as circulatory diseases, diabetes mellitus, which are present in our patient. Other conditions are psychiatric diseases, senile dementia, alcoholism and use of steroids, malnutrition, or any other immunosuppressive condition.10

Myiasis management is often executed by mechanical extraction more than through an antibiotic agent such as ivermectin.5–7 For our patient, the initial diagnosis was probably folliculitis or cellulitis and for that reason, she received treatment with dicloxacillin; however, myiasis was not considered as a differential diagnosis because it is not recognized as a prevalent entity in the patient's community. Furuncular presentation, as seen in our patient, can be differentiated from other like cavitary and post-traumatical myiasis because usually it is associated with only one larvae and by the presence of an important inflammatory response in wound site.

First-line pharmacological management of myiasis, as above mentioned, is performed by administration of ivermectin which generates a tonic paralysis of the larval muscles and has been shown both topically and orally to be a safe and effective medication.1,3,4,7–10

This patient was given a multidrug treatment for her clinical conditions; no drug interactions were reported; after nine doses, an allergic reaction to dicloxacillin was triggered, fortunately with reversible and mild side effects.

The patient informed that she removed the larvae by herself. It has been reported that a significant percentage of patients extract the larvae by themselves at the onset of the disease3; in the remaining cases, extraction is performed by pore blockage with grease, Vaseline or other substance that causes larvae suffocation, giving as a result the migration of the larva to the surface.1,3,4 Occasionally, the use of prophylactic antibiotics to avoid secondary infections is prescribed.4,7,10

In this clinical case, transmission was most likely caused by the hematophagous female Aedes, or Psorophora mosquito than by domestic flies or ticks, however people indicated the presence of ticks in dogs and some of them presented tick bites. We could observe house flies (Musca domestica) and adult stages of Aedes and Psorophora in the patient's household, and Psorophora larvae in the sewage nearby the patient's home (Fig. 4B and C).

The patient lives with a married couple, a dog (Canis lupus familiaris) and a cat (Felis catus); none of them reported having had myiasis yet the couple's youngest son had had myiasis the previous month.

An epidemiological survey of people living in the neighboring property to the right of the patient's house reported no animal or human myiasis. At this property there were three horses (Equus ferus caballus) and ornamental fishes. The horses were in good conditions and did not revealed skin injuries. In the neighboring property to the left, a dog had had myiasis two months ago. Two hundred meters away from the patient's home, we recorded a case of myiasis in a domestic dog a week ago and according to the supervisor of a drug abuse rehabilitation center, myiasis was reported in 15 young people in the last 5 years.

A lonely stray dog running on street was checked and it was unaffected; it is well-known that dogs are prone to be affected by myiasis.1

The rural physician of the Healthcare facility indicated lack of myiasis reports from October 2012 to May 2013, but he pointed out that these cases probably ended up being treated in San Rafael Hospital in Fusagasugá (Level II). According to information from the Cundinamarca Healthcare Secretary, the most prevalent diseases are diarrhea by 3.8% and allergies by 3%.

The patient stopped using dicloxacillin at her first control due to the side effects she experienced (hypersensitivity). We indicated to continue all drugs prescribed for diabetes, hypothyroidism and hypertension and keep on using topically 2% fusidic acid over the knee furuncle to prevent superinfection.5 During her second week control in Chinauta, she was instructed to stop using this agent due to closure of the wound.

The patient was followed-up for three weeks; she showed reduction in swelling of the affected area in the first week and remission of the furuncle in the second week. We recommended maintaining physical barrier methods through mosquito net and using insect repellents, and managing any future bite with topical fusidic acid and 1% hydrocortisone as well.

Native as well migrant population are at risk in Chinauta (4923 habitants in 2010 according to demographic report) but it could reach 5200 people, plus 4730 temporary residents during holidays seasons, as estimated by the mayor of the city13, ranging from elderly to young people and children. The ecological conditions for transmission are present, although some villagers reported achieving control of flystrike (“nuche”) both in animals and humans. This type of infestation produces deterioration of the quality of life and stigmatization of the individual.

Undoubtedly, the lack of sewages contributes to maintaining a suitable ecological niche for breeding of flies causing myiasis and, in the case of D. hominis, conveyors insect larvae. While there is underreporting of myiasis cases, population education, regular veterinary check-ups of animals, and sewers construction are crucial for reducing the insect reproduction and the rate of myiasis cases in this district.

There are two well-defined rainy periods in Chinauta; the first one from March to May and the second one from September to November, with a maximum of 320mm. The predominant vegetation in the patient's living environment corresponds to tropical dry forest with tree species such as mesquite trees (Prosopis juliflora), guacimo (Pithecellobiun), kapok (Ceiba pentandra), pelagic (Acacia Farneciana), balsa wood (Ochosroma spp.) and flycatcher (Croton ferrugineus).12

The area has several natural drainages or runoffs which have been clogged with farm fences, water diverted for the different crops and nurseries, ornamental lakes dammed to form water reservoirs which have been built without any technical design, and the dumping of contaminated wastewater from homes and farms, organic and chemical wastes.12

Chinauta has a high rate of vectors such as mosquitoes, flies and rodents, which are directly related to poor management of wastewater. Furthermore, factors such as hot weather, management of organic fertilizers in nurseries and the presence of sheds all contribute to the increase of the aforementioned vectors.12

Finally, myiasis has many etiological agents, several clinical presentations mainly on the scalp, arms or limbs skin although some cases may be found in the oral cavity14 and less commonly in other anatomic sites with subsequent complications.15

In conclusion, the emergence of cases of myiasis and the environment where they occur will be important factors that should be considered by the physicians when making the differential diagnosis of skin and mucous diseases in patients from areas with similar ecological characteristics to be reported here, that is from eco-epidemiological paradigm.16

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

We thank people and authorities of Chinauta corregiment, Dr. Jorge Molina, CIMPAT, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia for entomological study, Marina Sarmiento and Iveth Hernandez for support in laboratory at Military University and finally we thank Dr. Nélida Forero Cubides for her helpful review of English manuscript.