Acute liver failure (ALF) is a severe and potentially lethal clinical syndrome. It has been demonstrated that micro ribonucleic acids (miRNAs) are crucial mediators of nearly all pathological processes, including liver disease.

ObjectiveThe present study investigates the role of miR-378 in ALF. An ALF mouse model was induced using intraperitoneal injections of d-galactosamine/lipopolysaccharide (d-GalN/LPS). A hepatocyte cell line and miR-378 analogue were used in vitro to investigate the possible roles of miR-378 in ALF.

MethodsThe expressions of miR-378 and predicted target genes were measured via reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction and western blotting, and cell apoptosis was assayed using flow cytometry.

ResultsCompared with mice in the control group, the mice challenged with d-GalN/LPS showed higher levels of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6, more severe liver damage and increased numbers of apoptotic hepatocytes. Hepatic miR-378 was distinctly downregulated, while messenger RNA and protein levels of cysteinyl aspartate specific proteinase 9 (caspase-9) were upregulated in the ALF model. Furthermore, miR-378 was downregulated in d-GalN/TNF-induced hepatocyte cells, and miR-378 was found to inhibit hepatocyte apoptosis by targeting caspase-9.

ConclusionTogether, the present results indicate that miR-378 is a previously unrecognised post-ALF hepatocyte apoptosis regulator and may be a potential therapeutic target in the context of ALF.

La insuficiencia hepática aguda (ALF) es un síndrome clínico grave y potencialmente letal. Se ha demostrado que los microácidos ribonucleicos (miRNA) son mediadores cruciales de casi todos los procesos patológicos, incluida la enfermedad hepática.

ObjetivoEl presente estudio investiga el papel de miR-378 en ALF. Se indujo ALF en un modelo de ratón usando inyecciones intraperitoneales de d-galactosamina/lipopolisacárido (d-GalN/LPS). Se utilizaron una línea celular de hepatocitos y un análogo de miR-378 in vitro para investigar las posibles funciones de miR-378 en ALF.

MétodosLas expresiones de miR-378 y los genes diana predichos se midieron mediante la reacción en cadena de polimerasa cuantitativa con transcripción inversa y transferencia de Western, y la apoptosis celular se analizó mediante citometría de flujo.

ResultadosEn comparación con los ratones del grupo de control, los ratones desafiados con d-GalN/LPS mostraron niveles más altos de alanina aminotransferasa, aspartato aminotransferasa, factor de necrosis tumoral alfa e interleucina-6, daño hepático más grave y un mayor número de hepatocitos apoptóticos. El miR-378 hepático se reguló claramente a la baja, mientras que el ARN mensajero y los niveles de proteína de la proteinasa 9 específica de aspartato de cisteinilo (caspasa-9) se regularon al alza en el modelo ALF. Además, miR-378 se reguló a la baja en las células de hepatocitos inducidas por d-GalN/TNF, y se descubrió que miR-378 inhibía la apoptosis de los hepatocitos al interferir en la transcripción de la caspasa-9.

ConclusiónJuntos, los presentes resultados indican que miR-378 es un regulador de la apoptosis de hepatocitos post-ALF previamente no reconocido y puede ser un objetivo terapéutico potencial en el contexto de ALF.

Acute liver failure (ALF) is a fatal clinical syndrome caused by acute and severe liver attacks.1 Common ALF causes include viral hepatitis, drug overdose, idiosyncratic drug reactions and toxins.2 Currently, there are no effective ALF therapeutic strategies available, and liver transplantation remains the only treatment option; however, transplantation is often limited by a lack of donor livers. Therefore, a new therapeutic strategy is needed to alleviate and cure ALF. The pathologies underlying ALF are extensive necrosis and hepatocyte apoptosis.3 One ALF treatment approach is identifying and increasing the anti-apoptotic capacity of hepatocytes.

Micro ribonucleic acids (miRNAs) are a class of non-coding RNA molecules with 22–26 nucleotides4 involved in regulating almost all cellular and developmental processes via gene expression control. Currently, over 2000 miRNAs encoded by the human genome have been identified.5,6 Approximately 60% of all mammalian genes are regulated by miRNAs7; consequently, miRNAs also play key roles in various highly regulated processes, such as cell differentiation, proliferation and cell death.8 Because miRNAs can be tested in clinical samples, they also promise diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for many diseases.9

Furthermore, miRNAs play an important role in liver regeneration and might contribute to spontaneous ALF recovery.10 Previous studies have indicated that miR-378 limits liver fibrosis11 and ameliorates hepatic steatosis.12 It has been reported that miR-378 is associated with cell survival, tumour growth and angiogenesis13; it is also used as a biomarker for the early detection and prognosis prediction in hepatocellular carcinomas.14 Moreover, research indicated that activated caspase-9 could trigger a cascade of events leading to apoptosis. It means that caspase-9 is the essential initiator caspase required in the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway.30 It may play an anti-apoptotic role via the repression of caspase-9 expression in ALF. However, the role of miR-378 in ALF, along with the link between miR-378 and hepatocyte apoptosis, is unknown. We believe that the miRNAs may regulate hepatocyte apoptosis during ALF. The present study demonstrates that miR-378 is significantly downregulated in both in vivo (d-galactosamine/lipopolysaccharide [d-GalN/LPS] treatment) liver failure models and in vitro (d-GalN/tumour necrosis factor-alpha [TNF-α] stimulation) hepatocyte apoptosis to investigate the miRNAs involved in ALF. Functionally, miR-378 inhibits cysteinyl aspartate specific proteinase 9 (caspase-9) expression in hepatocytes, thereby decreasing cell apoptosis. Thus, the present data indicate that miR-378 is a potential candidate for novel ALF treatment strategies.

Materials and methodsAnimalsMale BALB/c mice (aged 6–8 weeks) were obtained from the Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China). The animals were housed under laboratory conditions, given free access to food and water and maintained in a pathogen-free facility. The animals were treated as recommended in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and both investigative and veterinary staff monitored the health and well-being of the mice used in the research; this level of responsibility and care, which is based on the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 2011), is mandated by the Public Health Service. For tissue and blood collection, the mice were anaesthetised using ether inhalation and euthanised using cervical dislocation. It was ensured that the animals were fully anaesthetised following ether administration by monitoring the breathing rate, limb tension, corneal reflex and skin algesthesia. The Wannan Medical College Laboratory Animals Care and Use Committee approved all ether use and animal experiments.

Experimental acute liver failure modelThe animals were randomly divided into two groups: the control group and the model group. The model group15 was intraperitoneally injected with 800mg/kg d-GalN (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 10μg/kg LPS (Sigma-Aldrich), whereas the control group was administered with the same doses consisting of only saline. The animals were euthanised at different time points (0, 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 and 24h), and blood and liver tissues were collected. After anaesthesia, blood samples (1.0ml each) were collected from the retroorbital venous plexus in all animals, and the mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. A certain quantity of heparinised blood was used to measure biochemical analysis and the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Liver tissues were collected for biochemical, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labelling (TUNEL) assay and immunohistochemistry analyses.

Serum cytokine analysis and liver enzyme measurementsSerum samples collected at 1 and 7h were analysed for cytokine levels using a Valukine ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were measured using a standard autoanalyser (Hitachi 7600–10, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

Histological analysisLiver tissues were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24h, paraffin-embedded and sectioned with a microtome to obtain 5-μm-thick sections. The sections were stained with haematoxylin–eosin and examined via light microscopy to evaluate the tissues for histopathological damage; the damage was evaluated under a fluorescence microscope (magnification 200×).

ImmunohistochemistryThe paraffin-embedded liver sections were treated with a 9.0 pH antigen retrieval buffer (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) at 100°C for 10min. The slides were then incubated with a rabbit anti-mouse caspase-3 antibody (1:200) (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) at room temperature for 1h and washed three times in Tris-buffered saline. Finally, they were incubated with Envision-polymer horseradish peroxidase rabbit antibody (Dako) at room temperature for 1h. The peroxidase activity was confirmed with diaminobenzidine, and images were captured using an orthophoto microscope (Nikon Corporation; magnification 400×).

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labelling assayThe DeadEnd Colorimetric TUNEL System (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) was used to examine liver tissue apoptotic cell death. Slides with formalin-fixed sections (5μm thick) were washed twice in xylene (5min each time), hydrated in 100% ethanol for 2min and washed in decreasing concentrations of ethanol (100%, 95% and 80%; 2min each time). The slides were then immersed in water for 2min and processed for TUNEL staining in accordance with the manufacturer's guidelines. An orthophoto microscope (Nikon Corporation; magnification 400×) was used to capture images.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)Total RNA was isolated from liver tissues and cultured cells using a Total RNA Isolation ReagentTRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), then reverse-transcribed into complementary deoxyribonucleic acid (cDNA). The resulting cDNA was quantified via real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the Synergy Brands SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Takara, Shiga, Japan) on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). The protocol for reverse transcription of messenger RNA (mRNA) and miRNA was 37°C for 15min, 85°C for 30s and 4°C for 5min. The expression levels of caspase-9, TNF-α and interleukin-6 (IL-6) were normalised to β-actin levels, whereas U6 served as the internal gene for miR-378. Relative gene expression levels were analysed using the 2−ΔCT method.16

Western blottingTotal protein from liver tissues or cells was lysed in a lysis buffer (Beyotime, Nantong, China), separated on a 10% sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to an Immobilon-P-polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Danvers, MA, USA). After blocking in 5% skim milk for 1h, the membranes were incubated with anti-caspase-3 (Abcam), anti-cleaved-caspase-9 (Abcam) or anti-β-actin (Abcam) overnight at 4°C. After washing with Tris-buffered saline/Tween-20, the membranes were incubated at room temperature for 2h with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobin G (1:2000, Sigma-Aldrich). Immunoreactive bands were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) western blotting detection system (Pierce/Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA).

In vitro induction of hepatocyte apoptosis and cell linesNormal murine embryonic liver cells (BNLCL2) were purchased from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Beijing, China) and cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum, 4mM glutamate and 1000U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco/Invitrogen). Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere under 5% CO2. In vitro hepatocyte apoptosis17 was induced by co-treatment with 1mg/ml d-GalN (Sigma-Aldrich) and 100ng/ml TNF-α (Sigma-Aldrich) added to the culture medium, whereas the control cells were grown in culture medium only. The cells were harvested for total RNA extraction and western blotting, and a fraction was collected for the apoptosis assays. An Annexin-V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (KeyGEN, Nanjing, China) was used to determine the cell apoptosis. Annexin-V-positive, propidium iodide (PI)-negative cells were defined as early apoptotic cells, whereas Annexin-V-negative, PI-positive cells were considered necrotic. The analyses were performed using a Beckman Gallios Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). Each measurement was repeated three times.

Plasmid construction and luciferase assaysThe BNLCL2 cells (5×104) were seeded in 24-well plates for 24h and transiently transfected with 5 ng of Promega Renilla Luciferase pRL-TK Renilla plasmid (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) combined with caspase-9 reporter luciferase plasmids (100ng), pGL3-caspase-9′ untranslated regions (UTR) (wt/mut) or control luciferase plasmids; these were transfected into the cells with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The luciferase activity was measured, and ratios of firefly luciferase luminescence to Renilla luciferase luminescence were calculated in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol.

Cell transfectionThe BNLCL2 cells were seeded in a six-well culture plate at a density of 2–4×105 cells per well for 24h. For experimental purposes, the cells were then transfected with a miR-378 mimic or miR-378 inhibitor (GenePharma, Shanghai, China) with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions for 24h. The negative controls included a non-specific mimic, non-specific inhibitor and Carboxyfluorescein FAM-negative control miRNA (GenePharma). The same amount of green fluorescent protein plasmid was also transfected as a control to test the transfection efficiency of the cells. The transfection efficiency of the cells reached 70–80% after 24h. The miR-378 mimic sequences were 5′-GCGGGTACCCTGGCTGCGCCTGCCTCAC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTGAGGCAGGCGCAGCCAGGGTACCCGC-3′ (reverse), the miR-378 non-specific mimic (NSM) sequences were 5′-GGGACAGGCTGTTGGCTGGATGGAGAGTGAGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCTCACTCTCCATCCAGCCAACAGCCTGTCCC-3′ (reverse), the miR-378 inhibitor sequences were 5′-GACAGAACCGCAAGGTAATCCATCCAGCCAACA-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACTTGTCACAACTCATGGGTGTGGCTGGATGGA-3′ (reverse), and the miR-378 non-specific inhibitor (NSI) sequences were 5′-CCCGGAGATACGGATTGCACGCAGCCAGGGTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCCTCGCGGTAATCATTTGCCCTGGCTGCGCC-3′ (reverse). Each measurement was performed three times. And miR-378-3p construct based on MirMap was used for mimics and inhibitors in vitro.

Statistical analysisAll data were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences 20.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The differences were assessed using a one-way analysis of variance, and multiple comparisons were conducted using Dunnett's T3 test. Data were expressed as mean±standard error of the mean. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

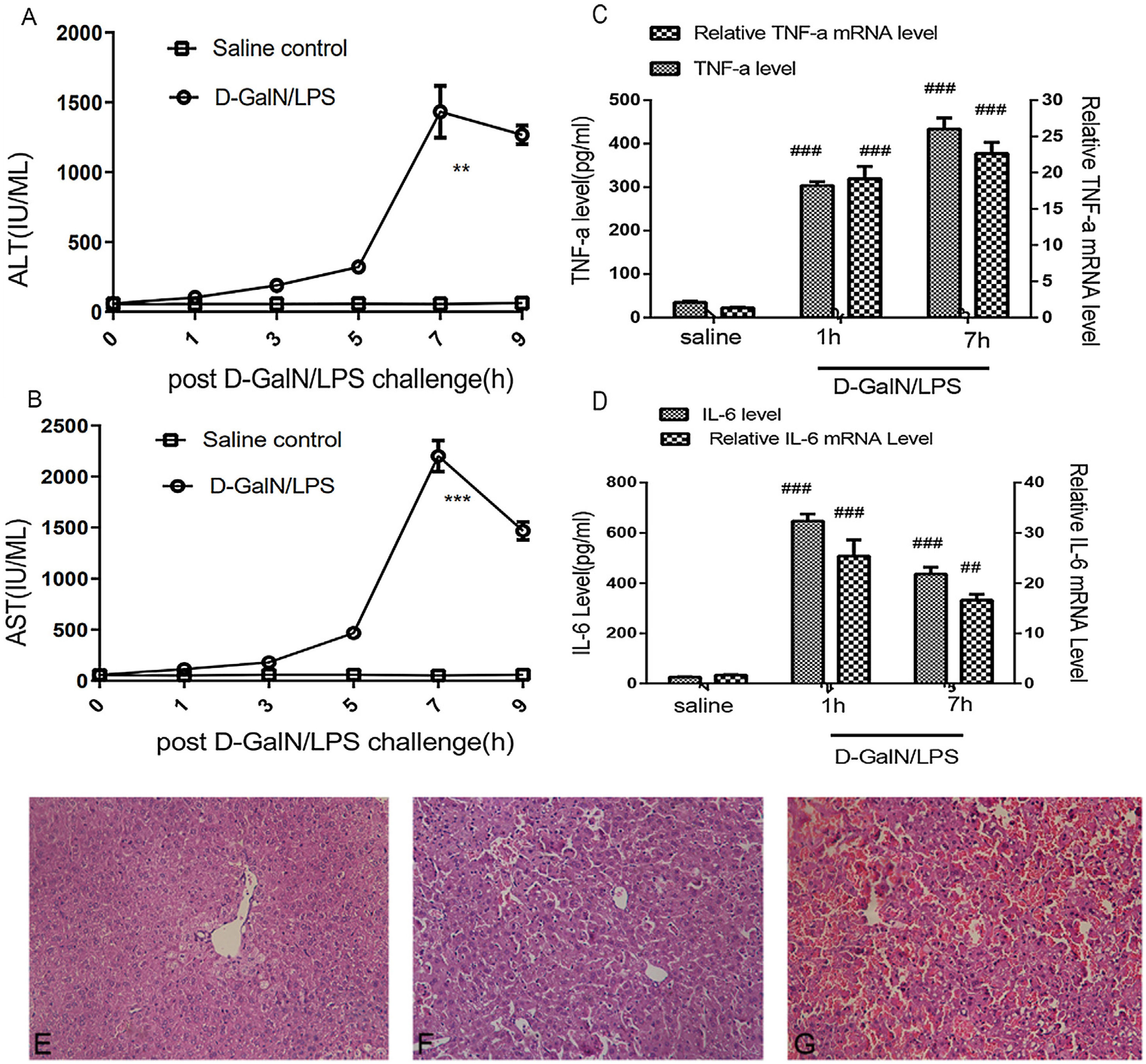

ResultsLiver injury in mice with acute liver failureThe model group was injected with d-GalN/LPS, while the control group was injected with saline only; the mice were then euthanised at specific time points (0, 1, 3, 5, 7 or 9h). Blood and liver tissues were collected for the liver enzyme, histopathology and inflammatory cytokine examinations. In order to test for hepatocyte necrosis, the serum levels of ALT and AST were measured. The present research showed that serum ALT and AST increased gradually and peaked at 7h post-d-GalN/LPS challenging in the model group (Fig. 1A and B). Moreover, hepatocellular disintegration, increased inflammatory cells and congested sinusoids were detected at 5h and 7h post-d-GalN/LPS challenging. Moreover, a mortality rate of 80% was detected at 24h post-d-GalN/LPS challenging (data not shown). The present research was conducted at the 5h and 7h time points. The control group showed no changes in serum liver enzymes.

Liver injury and histopathology. Serum ALT (A) and AST (B) release increased gradually and peaked at 7h post d-GalN/LPS challenge, as compared with values in the saline injection group (values are expressed as IU/ml). mRNA and serum concentrations of TNFα (C) and IL-6 (D) in the challenge group clearly increased at 1h and 7h. (E) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of liver tissues. No abnormalities were detected in the saline-treated group. (F) Increased inflammatory cells, slightly congested sinusoids and hepatocellular disintegration were detected a 5h post d-GalN/LPS-challenge. (G) Extreme damage at 7h post d-GalN/LPS-challenge. Results are presented as mean±SD; **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs the control group. ##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001vs control group. There are two groups, d-GalN/LPS and saline injection, with six time points (0, 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9h) for each group. There were three mice per time point for each group.

TNF-α and IL-6 play important roles in the d-GalN/LPS-induced liver failure hepatocyte apoptosis.18 The present study revealed that the TNF-α mRNA levels were clearly higher in the model group than in the control group at 1h and 7h (Fig. 1C). Accordingly, the serum concentrations of TNF-α were higher in the model group than in the control group at 1h and 7h. Similarly, the mRNA levels and serum concentrations of IL-6 were higher in the model group than in the control group at 1h and 7h (Fig. 1D). Haematoxylin and eosin histopathology in the control group showed no changes (Fig. 1E), whereas cell disruption, inflammatory cell infiltration and haemorrhage were detected at 5h (Fig. 1F) and 7h (Fig. 1G) in the model group. These data suggest that the d-GalN/LPS-challenged mice had severe liver injuries.

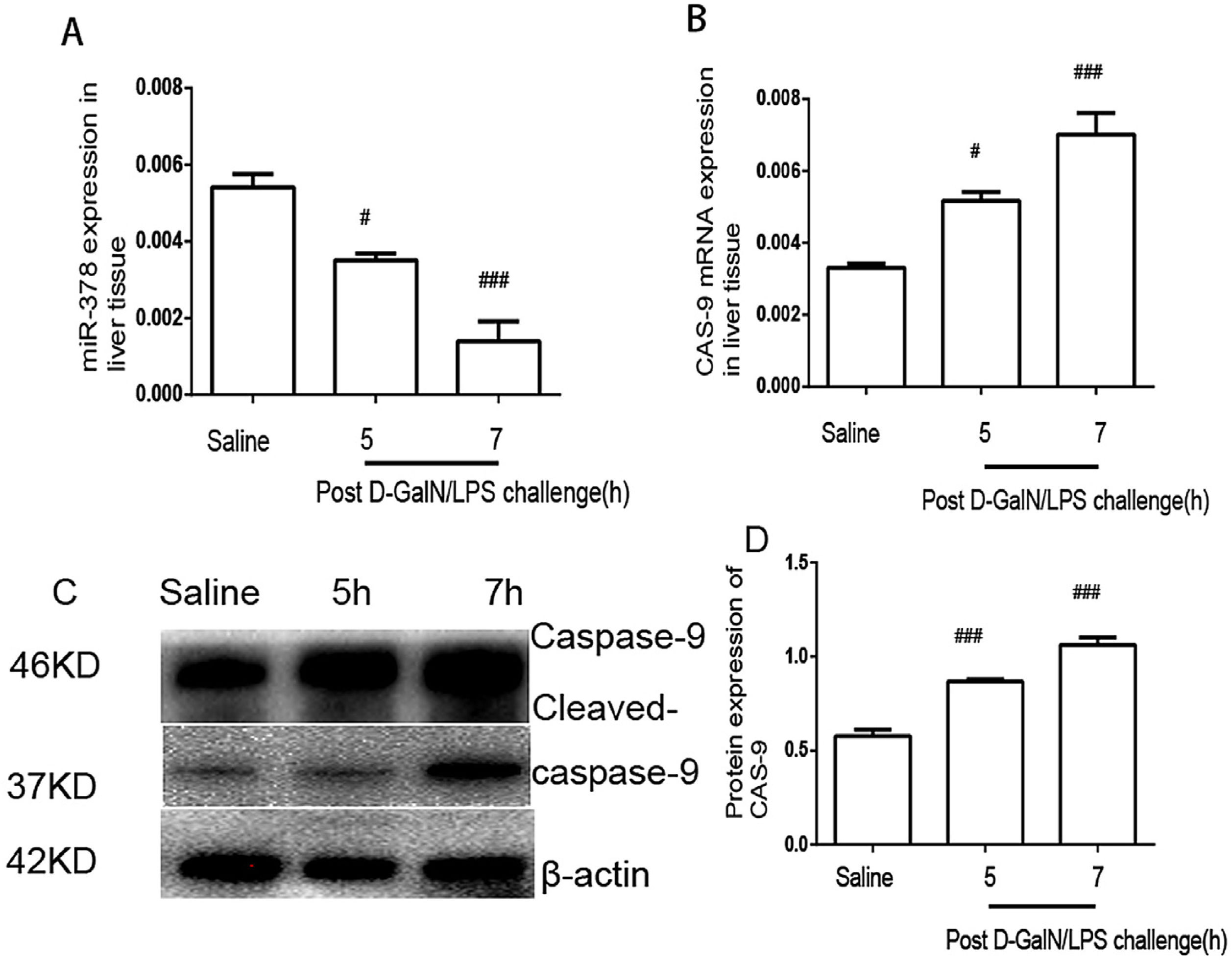

Acute liver failure model miR-378 downregulation and caspase-9 upregulationALT and AST in serum peaked at 7h after d-GalN/LPS stimulation (Fig. 1A and B), and samples at 5h and 7h after d-GalN/LPS stimulation were selected for the study. Compared with the control group, miR-378 showed a significant downregulation at 5h and 7h after d-GalN/LPS challenging in the model group (Fig. 2A). Moreover, the mRNA levels of caspase-9 were upregulated at 5h and 7h in the model group (Fig. 2B). Consistent with these results, the hepatic caspase-9 protein levels were upregulated in the model group (Fig. 2C and D).

MiR-378 down-regulation and caspase-9 up-regulation in liver tissues. qRT-PCR analysis of miR-378 (A) and caspase-9 (B) at 5h and 7h post d-GalN/LPS challenge compared with saline treatment. (C) Western blotting analysis of caspase-9 protein expression in the control and experimental groups. (D) The signal was quantified and data were normalized to values for β-actin. Results are presented as mean±SD; #P<0.05 and ###P<0.001 vs the control group.

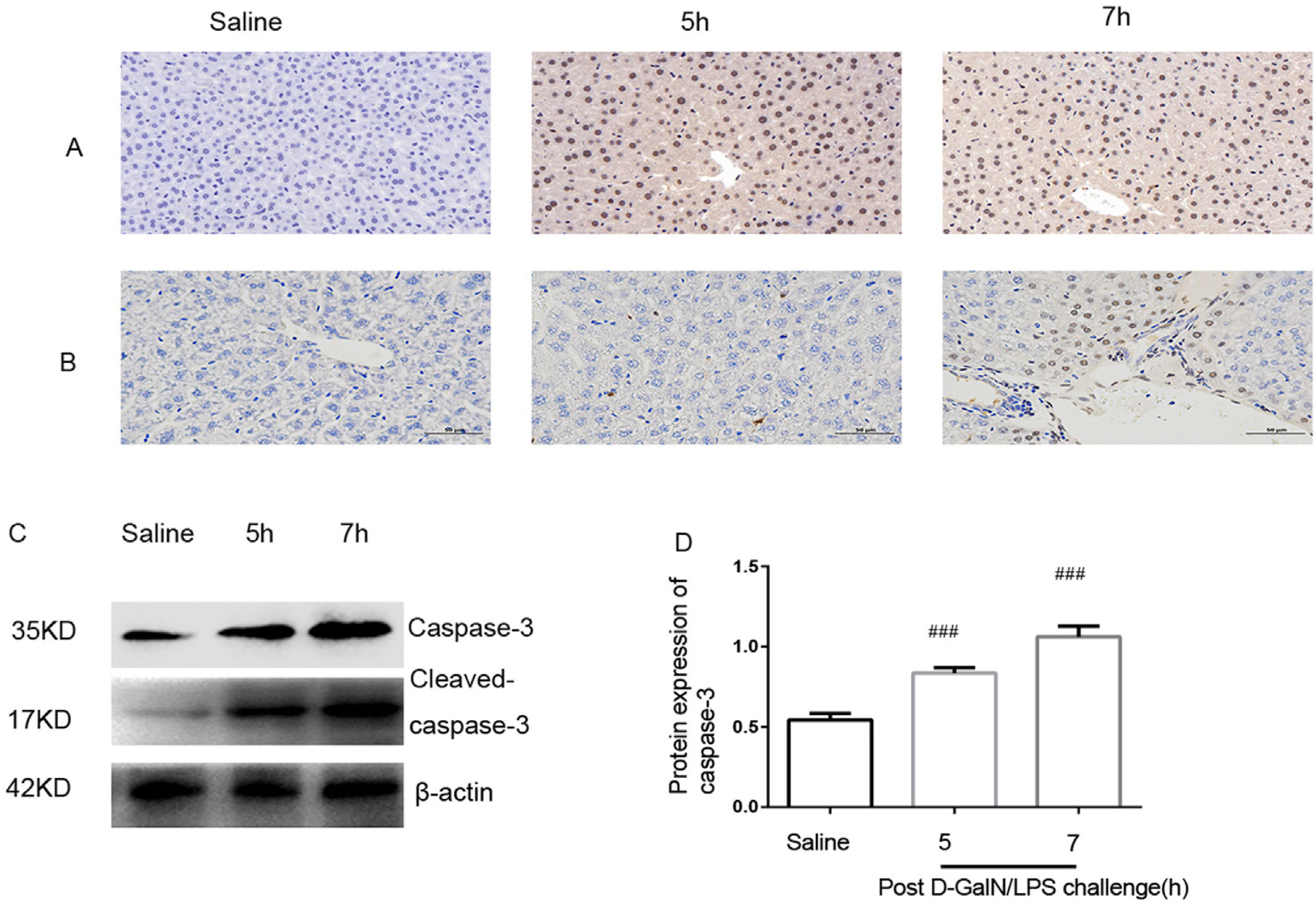

In order to test for hepatocyte apoptosis, the TUNEL assay and immunohistochemistry of liver tissues were examined. In the control group, there were no detectable caspase-3-positive cells. A substantial increase in caspase-3-positive staining was observed at 5h and 7h post-d-GalN/LPS challenging (Fig. 3A). The numbers of TUNEL-positive hepatocytes at 5h and 7h were significantly higher in the model group than in the control group (Fig. 3B). Meanwhile, western blot analyses showed increased caspase-3 at 5h and 7h in the model group (Fig. 3C and D). These results confirm that hepatocyte apoptosis was increased in the ALF model.

Hepatocyte apoptosis analysis. Apoptosis was observed through TUNEL assay and immunohistochemical staining of liver tissue after d-GalN/LPS and saline treatment. (A) Liver tissue immunohistochemical staining for caspase-3 in saline-treated group and at 5h and 7h after d-GalN/LPS challenge. (B) TUNEL staining of liver section in saline-treated group and at 5h and 7h after d-GalN/LPS challenge. (C) Western blot analysis of caspase-3. Compared with the saline-treated group, caspase-3 protein expression was higher at 5h and 7h post d-GalN/LPS challenge. (D) The signal was quantified and data were normalized to values for β-actin. Results are presented as mean±SD; ###P<0.001 vs the control group.

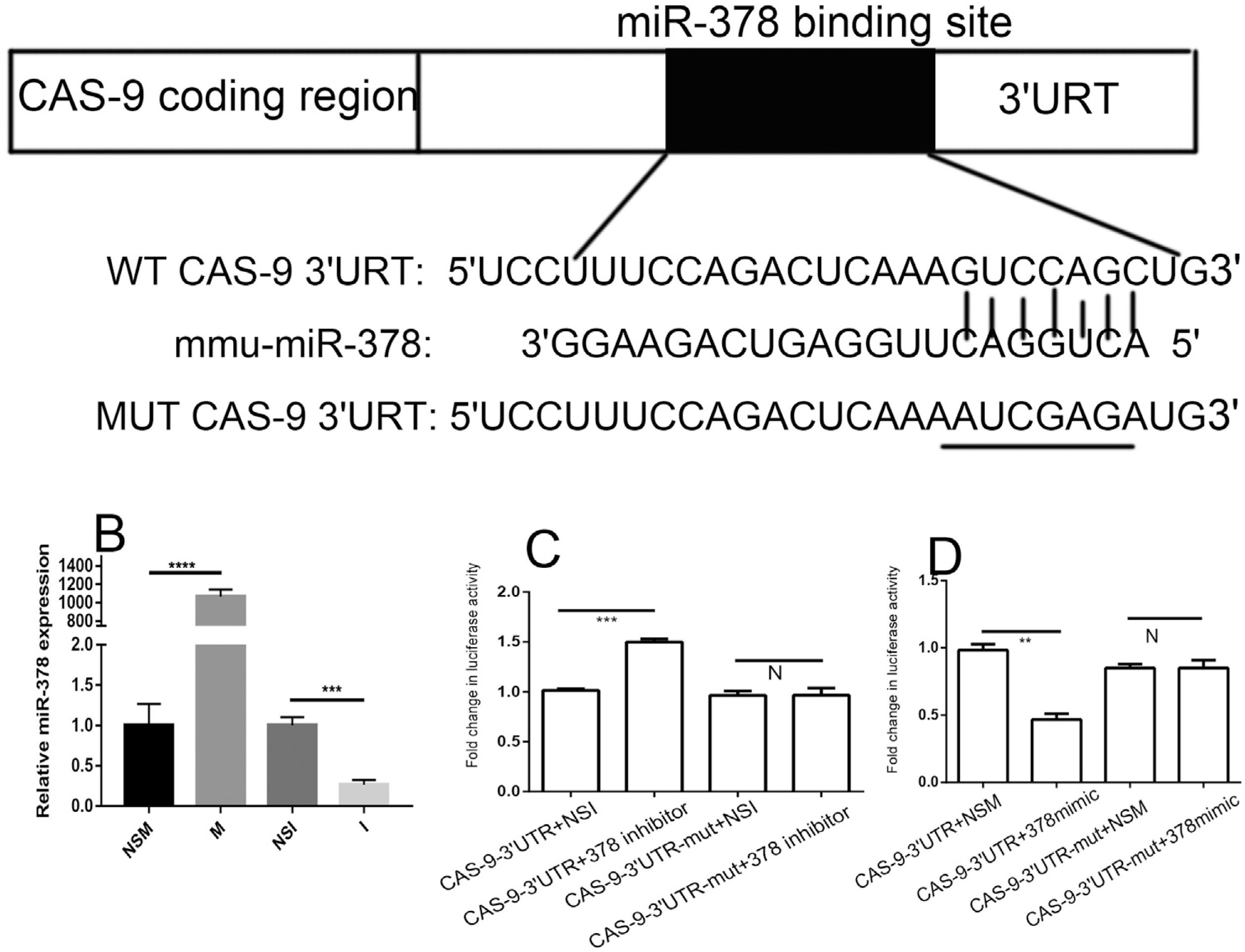

Luciferase reporter assays in the BNLCL2 cells were used to confirm the predicted miR-378 binding sites in the 3′UTR of caspase-9 (Fig. 4A). The pGL3-caspase-9–3′UTR (wt/mut) luciferase reporter plasmids and the miR-378 mimic, inhibitor, NSM and NSI were transfected into cells. qRT-PCR analysis was first used to examine transfection efficiency. The miR-378 mimic significantly increased the miR-378 levels, whereas the miR-378 inhibitor reduced the endogenous miR-378 levels in the BNLCL2 cells compared with the control miRNA (Fig. 4B). There was no difference in luciferase activity between the cells transfected with caspase-9–3′UTR-mut and the miR-378 inhibitor and the cells transfected with caspase-9–3′UTR-mut and miR-378 NSI (Fig. 4C). However, luciferase activity was approximately 47% higher in the cells transfected with caspase-9–3′UTR and the miR-378 inhibitor than in the cells transfected with caspase-9–3′UTR and miR-378 NSI (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, luciferase activity was approximately 52% lower in the cells transfected with caspase-9–3′UTR and the miR-378 mimic than in the cells transfected with caspase-9–3′UTR and miR-378 NSM (Fig. 4D). There was no difference in luciferase activity between the cells transfected with caspase-9–3′UTR-mut and the miR-378 mimic and the cells transfected with caspase-9–3′UTR-mut and miR-378 NSM (Fig. 4D). These results suggest that miR-378 directly binds caspase-9 regulatory sequences in their 3′UTR regions, thereby decreasing their expression in hepatocytes.

MiR-378 targets the caspase-9 mRNA 3′UTR in hepatocytes. Data from TargetScan revealed that caspase-9 is a predicted target gene of miR-378. (A) Predicted binding sites of miR-378 targeting the caspase-9 mRNA 3′UTR. (B) The efficacy of transfection was determined by qRT-PCR. pGL3-caspase-9–3′UTR (wt/mut) luciferase reporter plasmids were transfected with miR-378 inhibitor (C) or miR-378 mimic (D), and miR-378 non-specific inhibitor or non-specific mimic was transfected in the control group. Data represent the mean values for three independent experiments. Results are presented as mean±SEM. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; **** P < 0.0001; N, P>0.05.

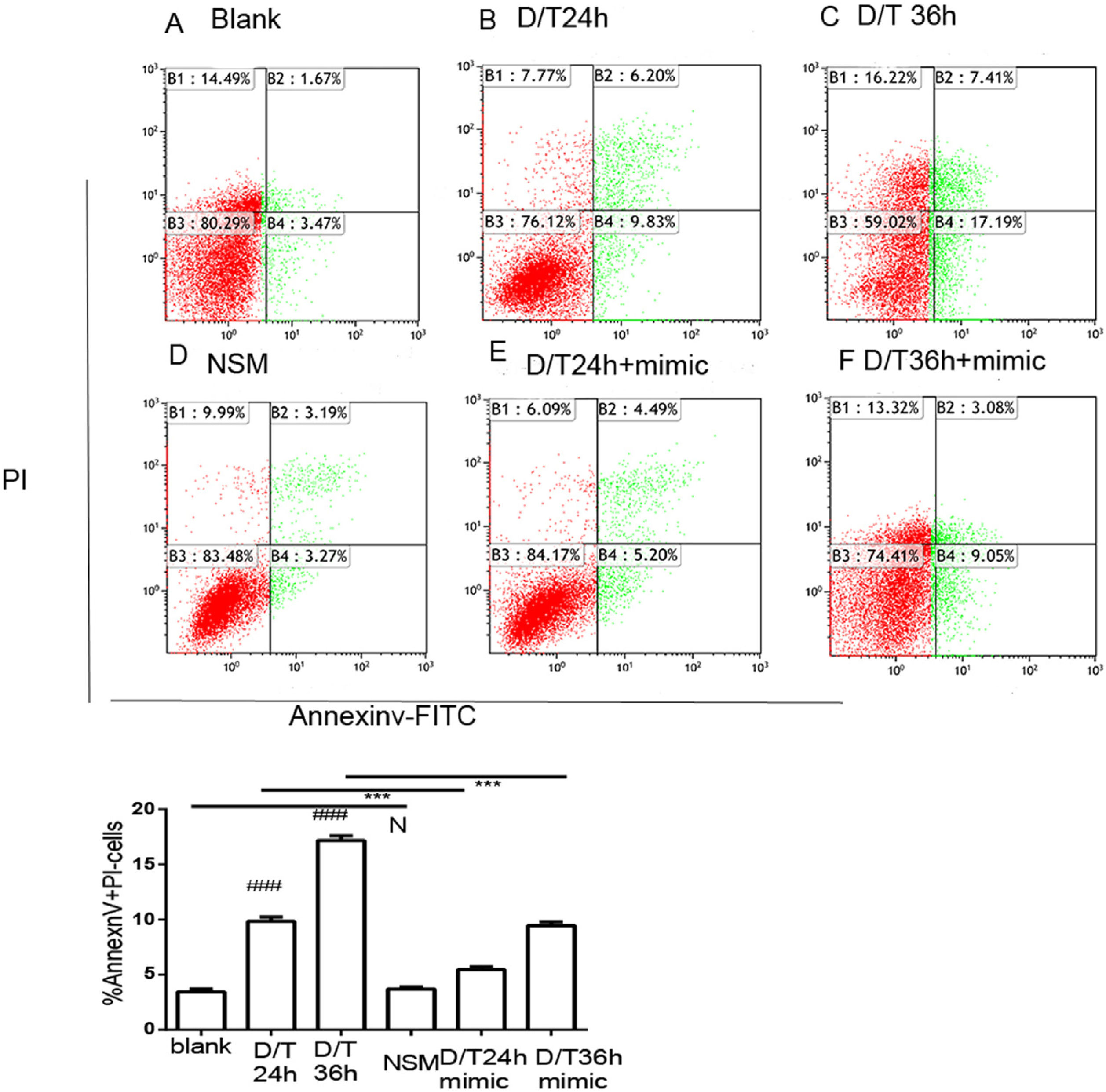

Given the previous results, it was next investigated whether miR-378 might regulate hepatocyte apoptosis in vitro. The flow cytometry data showed the apoptotic rate in the control group was 3.43% (Fig. 5A). The apoptotic rates of the BNLCL2 cells were 9.83% and 17.18% at 24h (Fig. 5B) and 36h (Fig. 5C), respectively, after d-GalN/TNF-α stimulation. There was no difference in the apoptotic rate of the BNLCL2 cells transfected with a non-specific miRNA mimic (Fig. 5D) when compared with the control group. However, the miR-378 mimic resulted in a lower apoptotic rate at 24h (5.43%) (Fig. 5E) and 36h (9.44%) (Fig. 5F) after d-GalN/TNF-α stimulation.

MiR-378 overexpression alleviates hepatocyte apoptosis in BNLCL2 cells. BNLCL2 cells were transfected with miR-378 mimic or non-specific mimic, incubated for various times with d-GalN/TNF or mock treatment, and then stained with Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide. Representative apoptotic flow cytometry data for the different conditions are shown. Apoptotic cells were Annexin-V+/PI−. The panels show blank treatment (A) and d-GalN/TNF challenge for 24h (B) or 36h (C). The cells were transfected with miR-378 non-specific mimic (D) then treated with DMEM only. The cells transfected with miR-378 mimic were treated with d-GalN/TNF for 24h (E) or 36h (F). Data represent the mean values for three independent experiments±SEM.###P<0.001vs blank; NSM vs blank, N, P>0.05; D/T24h+miR-378 mimic vs D/T24h, ***P<0.001; D/T36 h+miR-378 mimic vs D/T36h, ***P<0.001.

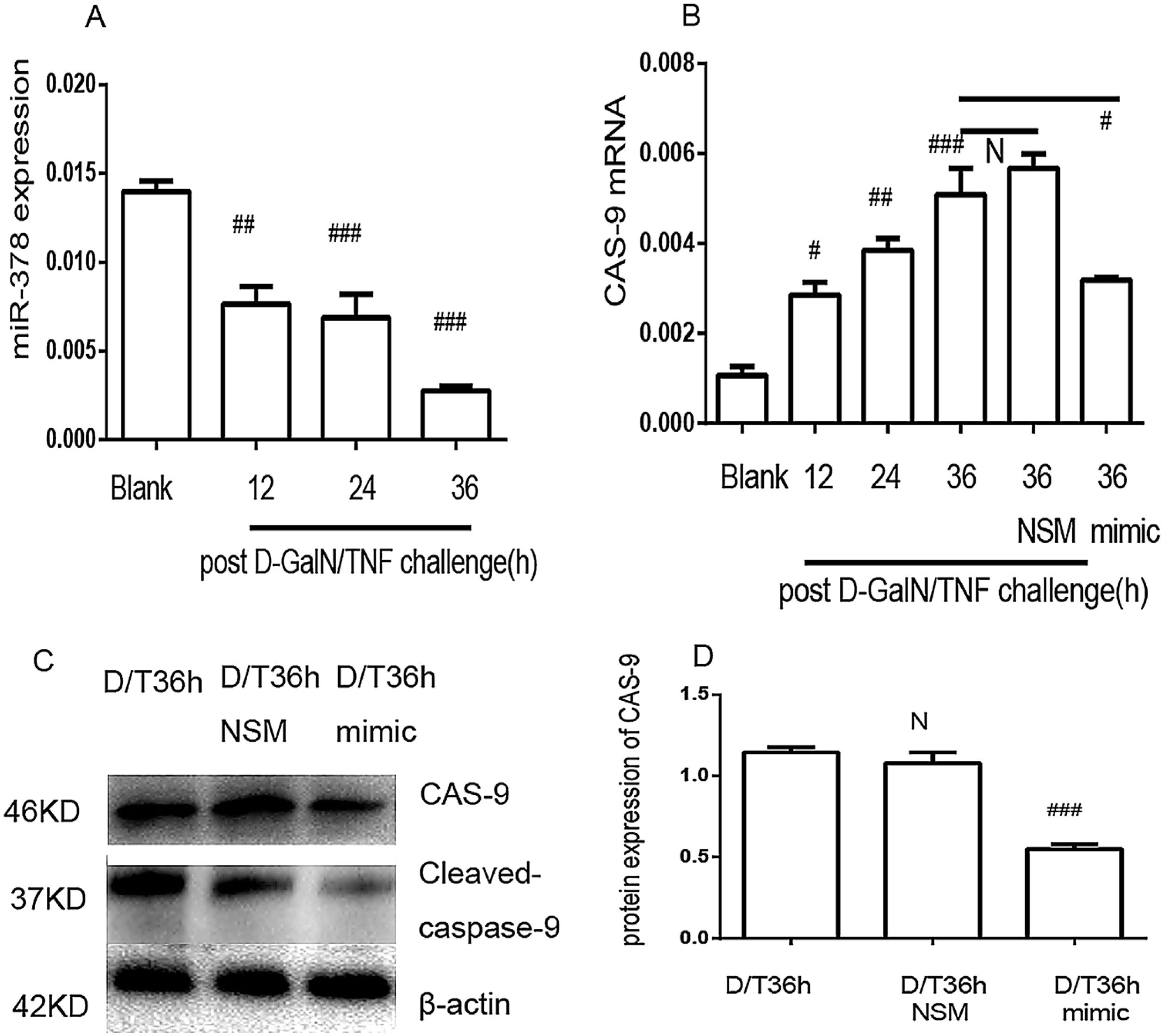

The in vitro results revealed that miR-378 was downregulated in the d-GalN/TNF-challenged group (Fig. 6A). In contrast, caspase-9 mRNA was upregulated after d-GalN/TNF challenging (Fig. 6B); these results are consistent with the in vivo results (Fig. 2A and D). No significant difference was detected in the cells transfected with the non-specific miRNA mimic after d-GalN/TNF challenging; however, caspase-9 mRNA was downregulated in the cells transfected with the miR-378 mimic after d-GalN/LPS challenging (Fig. 6B). Accordingly, caspase-9 protein expression was downregulated in the cells transfected with the miR-378 mimic at 36h post- d-GalN/TNF challenging (Fig. 6C and D). In conclusion, it was confirmed that miR-378 inhibits the expression of caspase-9 at both the mRNA and protein levels in vitro.

MiR-378 mimic attenuates caspase-9 expression in BNLCL2 cells. (A) qRT-PCR analysis of miR-378 at different time points post d-GalN/TNF challenge. (B) Caspase-9 qRT-PCR analysis in BNLCL2 cells transfected with miR-378 mimic or miR-378 non-specific mimic, followed by stimulation of d-GalN/TNF for 36h; the blank group was treated only with DMEM. (C and D) Caspase-9 western blotting in BNLCL2 cells transfected with miR-378 mimic or miR-378 non-specific mimic. Data represent the mean value of three independent experiments±SEM. N, P>0.05; #P<0.05; ##P<0.01; ###P<0.001.

Treatment with a combination of d-GalN and LPS is widely used in mouse studies researching the mechanisms underlying human ALF.19d-GalN/LPS co-treatment induces critical hepatic damage, accompanied by apoptotic and necrotic changes in the liver.20,21 Previous findings have suggested that miRNAs play roles in regulating death receptors as well as pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic genes.22 However, the relationship between miRNAs and apoptosis has not been fully elucidated in the murine ALF model. The present study hypothesises that miRNAs might regulate hepatocyte apoptosis in ALF.

miRNAs regulate protein expression by inducing mRNA degradation and repressing translation,23 and miR-378 has been extensively researched in relation to liver disease. However, whether or not miR-378 plays a role in ALF has not been reported. TNF-α plays a key role in the pathogenesis of d-GalN/LPS-induced ALF and liver apoptosis.15 The present data revealed that the expressions of TNF-α and IL-6 clearly increased in the model group. The ALF model was confirmed by histopathology and biochemistry, and it was demonstrated that mice with ALF showed higher mortality, more severe liver injury and higher serum ALT and AST levels. It was also found that miR-378 was downregulated in the in vivo ALF models and in vitro hepatocyte apoptosis. Thus, the present study concludes that miR-378 plays an important role in the ALF process.

Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death required for tissue homeostasis maintenance; this is achieved by counter-balancing cell proliferation and eliminating damaged, infected or transformed cells. Hepatocyte apoptosis is the major culprit underlying ALF. Excessive apoptosis, which results in excessive cell death, has potentially devastating effects and may lead to tissue destruction and ALF.24,25 In the ALF model, the liver tissue immunohistochemistry and TUNEL assay showed increasing hepatocyte apoptosis. In addition, the mRNA and protein levels of caspase-3 were upregulated. According to the present findings, hepatocyte apoptosis plays an important role in ALF, consistent with previously reported findings.

The results revealed that miR-378 could respond to hepatocyte apoptosis by blocking caspase-9 expression. Furthermore, the data show that a miR-378 mimic decreases caspase-9 mRNA and protein expressions, demonstrating that miR-378 regulates hepatocyte apoptosis by suppressing caspase-9 via mRNA degradation and translation.

Caspase-9 is activated via an interaction with the apoptosome complex, which self-cleaves and dimerises, forming an active enzyme that sequentially activates a downstream cascade.26 Caspase-9 activation occurs early in the caspase cascade (downstream of the intrinsic mitochondrial apoptosis pathway).27 Unlike executioner caspases, caspase-9 is not activated by cleavage but rather by dimerisation; this allows it to avoid adventitious activation.28 In ALF, the downregulation of miR-378 strengthens hepatocyte apoptosis by increasing the caspase-9 expression. In contrast, the upregulation of miR-378 leads to a decrease in the caspase-9 levels. Moreover, the present study provides evidence that caspase-9 is regulated by miR-378 at the post-transcriptional level. These results establish miR-378 as a gatekeeper of the hepatocyte apoptotic pathway in ALF.

ConclusionDuring in vivo and in vitro ALF, miR-378 was downregulated, whereas caspase-9 was upregulated. Moreover, miR-378 overexpression decreased hepatocyte apoptosis as well as the caspase-9 mRNA and protein levels in vitro. In addition, the present findings suggest that miR-378 directly targets the caspase-9 mRNA 3′UTR in hepatocytes. These findings are consistent with previous reports indicating that miR-378 inhibits apoptosis, targeting caspase-9 in cerebral ischemic injury.29 Thus, miR-378 overexpression might decrease caspase-9 expression and consequently inhibit hepatocyte apoptosis. These data suggest that miR-378 inhibits hepatocyte apoptosis by targeting caspase-9 during ALF; however, the precise mechanism connecting miR-378 to caspase-9 remains to be explored. The upstream regions of miR-378 are currently being investigated.

In summary, the present research provides evidence for an important miR-378 role in inhibiting hepatocyte apoptosis via suppressing caspase-9 in d-GalN/LPS-induced ALF. Caspase-9 was identified as a new target of miR-378 in hepatocytes. The present findings warrant further investigation in order to explore the intriguing possibility for ALF treatment.

Ethical approvalThis study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Wannan Medical College.

FundingThis work is supported by National Nature Science Foundation of China (81270438) and Youth Foundation of Wannan Medical College (KY24680368).

Authors’ contributionsZhiwen Feng conceived of the study, and Shenghua Bao and Lianbao Kong participated in its design and coordination and Xiaopeng Chen helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interestAll of the authors had no any personal, financial, commercial, or academic conflicts of interest separately.