A dysfunctional immune response is key to the pathogenesis of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF). It has been suggested that treatment with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) increases survival in patients with ACLF by improving immune cell dysfunction and promoting liver regeneration. The aim of the study is to evaluate the survival benefit associated with G-CSF administration compared with standard medical therapy (SMT) in ACLF.

MethodsSystematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. The primary outcome was survival at 60–90 days. We searched Ovid Medline, EMBASE, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from inception to August 2021. Manual searches of reference lists in relevant articles and conference proceedings were also included. The revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool was used for quality and risk of bias assessment. Two independent investigators extracted the data, and disagreements were solved by a third collaborator.

ResultsThe initial search identified 142 studies. Four randomized controlled trials were selected for quantitative analysis including 310 patients (154 G-CSF and 156 SMT). Significant heterogeneity was observed (I2=74%, Chi2=11.57, p=0.009). G-CSF administration did not improve survival in patients with ACLF (random-effects model, risk ratio=0.64 [95% CI 0.39, 1.07]). However, when considering only the results from the studies performed in Asia, a significant decrease on mortality was observed (risk ratio=0.53 [95% CI 0.35, 0.81]). Severity scores (MELD and Child) and CD34+ peripheral cells mobilization did not significantly improve with G-CSF.

ConclusionIn a systematic review and meta-analysis, G-CSF administration did not significantly improve overall survival compared to SMT in patients with ACLF. The beneficial effects observed in Asian studies, as opposed to the European region, suggest that specific populations may benefit from further research aiming to identify certain subgroups with favourable outcomes when using G-CSF.

La respuesta inmune disfuncional es clave en la patogénesis del fallo hepático agudo sobre crónico (ACLF). Se ha sugerido que la utilización de factor estimulante de colonias de granulocitos (G-CSF) aumenta la supervivencia de los pacientes con ACLF al mejorar la disfunción inmune y promover la regeneración hepática. El objetivo del estudio es evaluar el beneficio en supervivencia que proporciona la administración de G-CSF en comparación con el tratamiento médico estándar (SMT) en pacientes con ACLF.

MétodosSe llevó a cabo una revisión sistemática y meta-análisis de estudios aleatorizados y controlados. El objetivo principal fue analizar la supervivencia a los 60-90 días. Se realizó una búsqueda en Ovid Medline, EMBASE, y el registro central de estudios controlados de Cochrane desde su inicio hasta agosto 2021. También se realizaron búsquedas manuales en la bibliografía de artículos relevantes y presentaciones a congresos. Se utilizó la herramienta revisada de Cochrane para analizar la calidad y el riesgo de sesgos. Los datos fueron extraídos por dos investigadores independientes y las discrepancias fueron resueltas por un tercer investigador.

ResultadosLa búsqueda inicial identificó 142 estudios. De estos, 4 aleatorizados y controlados fueron elegidos para el análisis cuantitativo, incluyendo un total de 310 pacientes (154 G-CSF y 156 SMT). Se objetivó un alto grado de heterogeneidad entre los estudios (I2 = 74%, Chi 2 = 11.57, p = 0.009). La administración de G-CSF no aumentó la supervivencia en el grupo de pacientes con ACLF (modelo de efectos aleatorios, risk ratio = 0.64 [95% CI 0.39, 1.07]). Sin embargo, cuando se analizó el subgrupo de estudios realizados en Asia, sí se objetivó una disminución significativa de la mortalidad (risk ratio = 0.53 [95% CI 0.35, 0.81]). Las escalas de gravedad (MELD y Child) y la movilización de células CD34+ periféricas no mejoró significativamente tras la administración de G-CSF.

ConclusiónEn una revisión sistemática y meta-análisis, la administración de G-CSF no mejoró significativamente la supervivencia en los pacientes con ACLF en comparación con el tratamiento médico estándar. El efecto beneficioso observado en los estudios asiáticos frente a los europeos, sugiere que determinados subgrupos de pacientes, aun por determinar, podrían beneficiarse del uso de G-CSF en este contexto.

Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is characterized by acute decompensation of cirrhosis, hepatic and/or extrahepatic organ failure, and high short-term mortality.1 The activation of a dysfunctional immune response, featured by high-grade systemic inflammation and immune paralysis, is key to the pathogenesis.2 The immune alterations contribute to organ failure and increase the risk of infections, which significantly worsen prognosis and increase mortality.2 Treatment for ACLF is based on organ support and correction of the precipitating events when possible. Liver transplantation is often the only life-saving option in severe cases.3 However, transplantation for critically ill patients is restricted to selected candidates with favourable prognostic factors and is subjected to organ availability. Therefore, new therapeutic approaches targeting the immune response are under evaluation aiming to improve outcomes and survival in this clinical scenario.

The granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) is a recombinant protein that mobilizes bone marrow-derived hematopoietic stem cells. It has been shown that G-CSF also increases hepatocyte growth factor and induces hepatic progenitor cells proliferation in patients with alcoholic steatohepatitis.4 In ACLF, it has been suggested that G-CSF therapy may significantly increase survival at 60 days, reduce severity scores, and prevent the development of sepsis, hepatorenal syndrome, and hepatic encephalopathy.5 Despite encouraging results from animal models6 and small clinical trials,7,8 recent evidences from a large randomized multicenter study showed that G-CSF has no survival benefit nor therapeutic effect in ACLF.9 In light of the new evidences, this systematic review and meta-analysis aims to evaluate the impact of G-CSF therapy in patients with ACLF, focusing on the survival benefit against standard of care.

MethodsThis systematic review and meta-analysis has been performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Statement (PRISMA) guidelines.10 The protocol has been registered, and it is available at PROSPERO (CRD42020140178).

The studies included in this meta-analysis were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that met the following inclusion criteria: (1) patients: adults presenting with ACLF, (2) intervention: subcutaneous G-CSF administration; (3) comparison: placebo and/or standard medical therapy (SMT); and (4) outcomes: mortality (60–90 days). Depending on the geographical area where the studies were performed, ACLF was defined by the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL)11 criteria (“Acute hepatic insult manifesting as jaundice and coagulopathy, complicated within four weeks by ascites and/or encephalopathy in a patient with previously diagnosed or undiagnosed chronic liver disease”), or by the European Association for the Study of the Liver-Chronic Liver Failure (EASL-CLIF) criteria1 (acute decompensation with organ failure defined by the SOFA-CLIF score). Secondary outcomes included: reduction of severity scores (MELD and Child-Pugh scores), peripheral CD34+ cells mobilization, and adverse events.

We excluded for the quantitative analysis: (1) nonrandomized and observational studies; (2) studies including patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis but no ACLF, or when ACLF criteria were not specifically evaluated; and (3) RCTs where the primary outcome (survival) was not specified for the group of patients with ACLF.

Search strategyThe search strategy was designed by an expert medical librarian (NAD) in collaboration with the clinical investigators. Ovid Medline, EMBASE, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were analyzed from inception to August 2021. No language restriction was applied. Manual searches of reference lists in relevant articles, previous meta-analysis,12 and conference proceedings from the European, North America, and Asian associations for the study of the liver were also evaluated (2009–present). Additional ongoing or unpublished trials were identified through searches in clinicaltrials.gov database (https://clinicaltrials.gov/). The detailed search strategy can be found as Supplementary Material. Corresponding authors of the included studies were contacted to request unpublished information when deemed appropriate.

Study selection and data extractionTwo investigators (RM and RG) independently screened all titles and abstracts and reviewed the full text of the relevant studies. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and the intervention of a third collaborator and/or the senior author. RM and RG extracted data from the selected studies using a standardized data extraction excel sheet. The following information was collected from each study: title, first author name, year and journal of publication, sample size, primary endpoint, ACLF criteria, number and location of recruiting centres, study period, intervention (G-CSF dose, frequency, route, and duration of administration), comparison (placebo and/or standard of care), patient characteristics (sex, age, MELD and Child score pre and post-intervention), overall survival, adverse events, ACLF precipitating events, and cirrhosis aetiology.

Risk of bias and quality assessmentThe risk of bias was assessed independently by two investigators (RM and RG) using the revised Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 tool for randomized trials (RoB 2).13 The following domains were evaluated: (i) risk of bias arising from the randomization process, (ii) risk of bias due to deviations from the intended interventions, (iii) missing outcome data, (iv) risk of bias in the measurement of the outcome, and (v) risk of bias in the selection of the reported result. Follow-up of the subsequent publication of registered protocols and/or abstracts presented at international meetings was analyzed to evaluate possible publication bias.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analyses were performed with STATA version 13 (Stata Corp, Texas, USA). Forest plots were created with Review Manager version 5.3 (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014). A senior medical statistician (AM) guided and supervised the study design, elaboration, and data analysis.

All analyses were conducted according to the intention-to-treat principle. Both the random-effects model and the fixed-effect model were calculated. Assessment of heterogeneity was quantified using the Higgins I2 statistic and classified as follows: I2 <40%=low; I2 30–60%=moderate; 50–90%=substantial, and >75%=considerable heterogeneity.14 When I2 was equal to or higher than 30%, the random-effects model was reported. The pooled risk ratio (RR) was estimated for binary outcomes (survival), and the standardized mean difference was reported for continuous outcomes (MELD and Child). The 95% confidence intervals and two-sided p values were estimated for each outcome.

Sensitivity analysis was performed by comparing the obtained results with different statistical methods (inverse variance and Mantel-Haenszel), different measures of effect (risk ratio and odds ratio), and assessing the consistency of the results among different prognostic scores.

ResultsOne hundred and forty-two RCTs were identified through database searching (37 Ovid Medline, 105 EMBASE). Three additional studies were included after manual searches of conference proceedings and in clinicaltrials.gov database. Fifteen duplicates were removed, and therefore, 129 references were considered for screening. Based on the title and abstract, 117 were excluded, and, finally, 12 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 4 RCTs5,7–9 were selected for the quantitative analysis. The PRISMA flow diagram and the reasons for exclusion are shown in Fig. 1.

Overall, the selected studies included a total of 310 patients (154 received G-CSF and 156 placebo and/or standard of care). ACLF was defined by the APASL criteria in all but one study,9 which applied both the EASL-CLIF and the APASL criteria obtaining similar results.

Two different G-CSF regimens were administered: 5μg/kg/day for six consecutive days (Duan et al. and Saha et al.), and 5μg/kg on a daily basis for the first 5 days and every third day thereafter until day 26 (12 doses) (Garg et al.5 and Engelmann et al.9). Three studies were unicenter RCTs performed in Asia,5,7,8 while the GRAFT9 trial recruited patients from 18 German tertiary centres. The underlying liver diseases were predominantly chronic hepatitis B (Saha et al. and Duan et al.) and alcoholic liver disease (Garg et al. and Engelmann et al.9). Accordingly, the precipitating events leading to ACLF were mostly related to hepatitis B reactivation and alcoholic hepatitis. These and other key features of the studies are further detailed in Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included studies.

| Author | Year | Location | Study period | No. of patients | Primary endpoint | ACLF criteria | Sex (% male) | Age (years) | MELD scoreG-CSF | MELD scoreSMT | Child scoreG-CSF | Child scoreG-CSF | ACLF precipitating event | Aetiology of the liver disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garg et al.5 | 2012 | IndiaUnicenter | 12/2008–08/2010 | 47 | 60-day survival | APASL | 87% | 40(19–65) | 29(21–40) | 31.5(20–40) | 12(11–14) | 12(10–14) | 27 AH, 10 HBV reactivation, 3 DILI- TBC, 3 HEV, 4 cryptogenic | 9 ALD, 13 HBV, 6 cryptogenic, 1 Wilson’disease |

| Duan et al.8 | 2013 | ChinaUnicenter | 06/2009–05/2011 | 55 | 90-day survival | APASL | 79.5% | 44.7(22–65) | 29(21–40) | 26.3±4.12 | 12.17±1.47 | 12.25±1.29 | HBV ACLF | HBV |

| Saha et al.7 | 2017 | BangladeshUnicenter | NA (2 years of enrollment) | 32 | 90-day survival | APASL | 87% | 43.5(18–62) | 24.5(21–32) | 255(21–35) | 12(10–13) | 12(10–14) | 19 HBV reactivation, 2 HEV, 6 DILI, 4 cryptogenic | 29 VHB + 1 Wilson + 1 AIH+1 cryptogenic |

| Engelmann et al.9 | 2021 | GermanyMulticenter(18 centres) | 03/2016–04/2019 | 176 | 90-day transplant free survival | EASL-CLIF (also APASL) | 63.1% | 55.7±9.9 | 24.4±6.3 | 24.5±6.1 | NA | NA | 54% alcohol related, 39.2% bacterial infections | NA |

NA: not available; ACLF: acute-on-chronic liver failure; APASL: Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver; EASL-CLIF: European Association for the Study of the Liver-Chronic Liver Failure; MELD: Model for End-stage Liver Disease; G-CSF: granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; SMT: standard medical therapy; AH: alcoholic hepatitis; HBV: hepatitis B virus; DILI: drug-induced liver injury; TBC: tuberculosis; HEV: hepatitis E virus; ALD: alcohol-related liver disease.

The meta-analysis did not show a significant survival benefit in the group of patients treated with G-CSF when compared to SMT (random-effects model, risk ratio=0.64 [95% CI 0.39, 1.07]) (Fig. 2). Although three studies suggested an improved survival, the GRAFT trial, which includes the largest number of patients shifted the tendency towards a non-significant overall outcome. In particular, this study is an interim analysis of a multicenter RCT that was prematurely terminated due to futility after conditional power calculation when 50% of the patients reached the primary endpoint or an event-free 90-day follow-up. The results were consistent with different measures of effect (odds ratio=0.35 [95% CI 0.11, 1.08]) and statistical methods (inverse variance and Mantel-Haenszel) (Supplementary Figure 1). Significant heterogeneity was observed (I2=74%, Chi2=11.57, p=0.009), mainly due to conflicting results among studies performed in Asia (favourable outcomes) and the European study9 which showed a non-statistically significant increase in mortality in patients receiving G-CSF. Considering the different results obtained in the Asian trials, we performed an additional meta-analysis including only these studies (Fig. 3). The analysis showed a significant favourable effect on survival in this subgroup of patients (random-effects model, risk ratio=0.53 [95% CI 0.35, 0.81], and random-effects model, odds ratio=0.21 [95% CI 0.10, 0.46]), which suggest possible underlying differences in patient selection, disease aetiology and the subsequent clinical management when comparing European vs Asian studies.

At baseline, MELD and Child scores were comparable in all groups (intervention and placebo/SMT). Engelmann et al. found that the distribution of patients with increasing or decreasing MELD or CLIF-C OF score (delta values between baseline and day 28) did not differ between those receiving SMT or G-CSF. On the contrary, the studies from Saha, Duan, and Garg showed a significant decrease in MELD and Child values following treatment with stimulating factors. There was not enough available information to perform a quantitative analysis, but the specific values provided by each study can be found in Table 2.

Secondary outcomes: evaluation of severity scores.

| Author | Severity score | G-CSF | Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saha BK et al. | MELD (baseline) | 26.4±4.6 | 25.3±3.3 |

| MELD (30 days) | 16.6±3.5 | 13.6±4.1 | |

| Child (baseline) | 12±1.2 | 11.9±1 | |

| Child (30 days) | 9.2±1.8 | 7.6±1.3 | |

| Garg V et al. | MELD (baseline) | 29 (21–40) | 31.5 (20–40) |

| MELD (30 days) | −18.23% | +6.25% | |

| Child (baseline) | 12 (11–14) | 12 (10–14) | |

| Child (30 days) | −15% | 0% | |

| Duan X-Z et al. | MELD (baseline) | 25.11±3.3 | 26.3±4.12 |

| MELD (30 days) | 23.3±6.9 | 29.8±5.7 | |

| Child (baseline) | 12.17±1.47 | 12.25±1.29 | |

| Child (30 days) | 11.17±2.76 | 12.86±2.63 | |

Bone marrow-derived hematopoietic stem cells mobilization was analyzed in only two clinical trials. Garg et al. studied CD34+ cell population in liver tissues and peripheral blood samples. They found a significant increase in hepatic CD34+ cells at 30 days. Conversely, they observed a significant decrease in peripheral CD34+ cells after 4 weeks of treatment with G-CSF when compared to baseline values, and no differences between the groups of treatment and SMT at this time point. On the other hand, Duan et al. described the kinetics of peripheral CD34+ counts, showing an early significant increase (days 3 and 7), followed by a progressive decline from day 15 onwards, so that on day 30, CD34+ cell counts were similar in both groups.

Severe adverse eventsOverall, G-CSF therapy was acceptably tolerated, and no deaths directly related to the study drug were reported. Garg et al. described a transient rash and high fever, which lead to the omission of one dose in two patients, and a herpes zoster reactivation treated with acyclovir at the end of the study period. Duan et al. reported minor side effects, including fever, headache and nausea. On the other hand, Engelmann et al. reported 57 serious adverse events in the SMT group, and 61 in the G-CSF+SMT group (7 of them considered drug-related).

Risk of bias and quality assessmentThe risk of bias was assessed with the revised Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 tool for randomized trials (RoB 2).13 The analysis showed an overall high risk of bias in two studies7,8 (Fig. 4). The main concerns were raised on the “selection of the reported result” domain and also derived from potentially selected populations due to the small sample sizes (Fig. 3). Two trials were registered in clinicaltrials.gov,5,9 where the study protocols are available. Of note, in the study from Garg et al., survival at the end of the study period (2 months) was not specifically defined as a primary or secondary outcome.

We further investigate the risk of bias by analyzing possible selective publication of manuscripts based on the magnitude or direction of the results. We did not generate a funnel plot due to the limited number of manuscripts included. Therefore, we analyzed the subsequent publication of full-length texts of registered protocols and/or abstracts submitted to international meetings. Interestingly, we found one abstract presented at the United European Gastroenterology week 2017 described as a 1:1 RCT using G-CSF vs placebo for patients with decompensated liver disease and ACLF.15 The authors published later on a full-text paper with a cohort of patients enrolled during the same period of time. However, this study was described as observational with no control group.16 Additionally, Di Campli et al. published a study where patients with ACLF were randomized to receive two different doses of G-CSF vs standard of care.17 Favourable data on CD34+ mobilization were reported, but information regarding patient survival was not mentioned nor subsequently published to date. Finally, a study protocol aiming to analyze the efficacy of G-CSF and Erythropoietin in patients with ACLF was registered in 2011 (NCT01383460), however, no results have been posted so far. Conversely, a similar RTC evaluating the survival benefit of G-CSF and Erythropoietin in patients with decompensated cirrhosis but, specifically, with no ACLF was published in 2015 by the same group of investigators showing promising results on survival and clinical outcomes.18 Together all this information suggests a possible publication bias towards underreporting negative results for G-CSF in the context of ACLF.

DiscussionACLF is a severe complication of cirrhosis characterized by high short-term mortality.1 Standard of care includes treatment of the precipitating event when possible and supportive care for organ failure. The immune dysfunction associated with ACLF2 and its potential reversibility have promoted therapeutic approaches targeting the high-grade systemic inflammation and immune deficiency that characterize ACLF. This systematic review and meta-analysis aim to evaluate the impact on survival of G-CSF administration, a glycoprotein that stimulates the bone marrow to produce neutrophils and stem cells (CD34+). Our study found that G-CSF has no significant therapeutic effect when compared to the standard of care. Interestingly, there was conflicting results among studies depending on the geographical area where they were performed (favourable results in Asia, and no benefit in European centres).

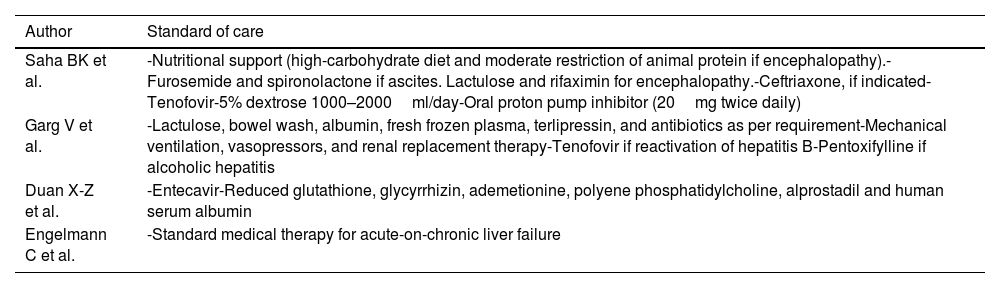

Disparities on the effect of G-CSF according to the recruiting centers’ location may potentially be related to several factors. First, differences in general clinical practice and the standard of care may have an impact on the results. In this regard, we observed substantial differences concerning the standard of care protocols (Table 3), and the access to liver transplantation, which may influence both, short and long-term survival. Second, two different regimens of G-CSF were applied: 5μg/kg/day during six consecutive days,7,8 and 5μg/kg/day during 5 consecutive days and then, every 3 days until completing 12 doses.5,9 It could be speculated that the studies with higher number of doses would show better outcomes. However, the study from Engelmann et al., that was early terminated due to futility, applied the extended protocol. In addition, RCTs from Asia included a higher number of patients with HBV-associated ACLF (Duan 55/55; Saha 19/32; Garg 10/47). These patients received specific pharmacological therapy with oral antivirals, which could have result in better outcomes as compared with supportive care alone in other etiologies with no specific treatment.19 Nevertheless, the number of patients who received specific therapies in each group (placebo or control) was largely unavailable, and thus, the effect of this factor remains uncertain. Finally, the use of different criteria to define ACLF influences the selection of the patients enrolled in each centre. It could be argued that patients enrolled under the EASL-CLIF definition may present a more severe disease due to the specific requirements on organ failure necessary to meet the criteria. However, this is not supported by the reported MELD scores at presentation, which were higher in the Asian centres (Table 1). In addition, Engelmann et al. performed a post hoc subgroup analysis including 114 patients who meet de APASL criteria for ACLF. In this subgroup, the administration of G-CSF did not result in higher survival rates as compared with standard of care. The authors observed a similar HR as the one obtained for the whole cohort (HR: 1.233 (0.762; 1.963), p=0.404) (APASL subgroup, 114 patients) vs HR: 1.05; 95% CI 0.711–1.551; p=0.805 (whole cohort, 176 patients). This suggest that the differences observed among Asian and European centres may not be completely explained by the different ACLF definition. Therefore, the specific reasons underlying the observed regional disparities remain unclear, and additional data will be required to clarify this question.

Description of the standard medical therapy applied in selected studies.

| Author | Standard of care |

|---|---|

| Saha BK et al. | -Nutritional support (high-carbohydrate diet and moderate restriction of animal protein if encephalopathy).-Furosemide and spironolactone if ascites. Lactulose and rifaximin for encephalopathy.-Ceftriaxone, if indicated-Tenofovir-5% dextrose 1000–2000ml/day-Oral proton pump inhibitor (20mg twice daily) |

| Garg V et al. | -Lactulose, bowel wash, albumin, fresh frozen plasma, terlipressin, and antibiotics as per requirement-Mechanical ventilation, vasopressors, and renal replacement therapy-Tenofovir if reactivation of hepatitis B-Pentoxifylline if alcoholic hepatitis |

| Duan X-Z et al. | -Entecavir-Reduced glutathione, glycyrrhizin, ademetionine, polyene phosphatidylcholine, alprostadil and human serum albumin |

| Engelmann C et al. | -Standard medical therapy for acute-on-chronic liver failure |

Our findings are in line with previously published data in children with ACLF,20 and with a recent meta-analysis about the effect of G-CSF in patients with alcoholic hepatitis.21 The authors of this meta-analysis also observed high heterogeneity in the overall analysis due to conflicting results between the Asian and the European centres. They conclude that G-CSF cannot be currently recommended until further evidences on its usefulness and the target population are available. This statement can also be applied to our study, that shows variable results depending on the location of the centres, and, also, a possible bias towards underreporting negative results.

This meta-analysis has several limitations that have to be acknowledge. First, a relatively small number of studies were included in the quantitative analysis. We selected only RCTs aiming to avoid the potential bias derived from observational study designs. In addition, we specifically choose RCTs focused on the effect of G-CSF in patients with ACLF. This requirement excluded several trials where G-CSF was administered in the context of an acute decompensation of cirrhosis or acute alcoholic hepatitis with no ACLF. As the immune dysfunction has been widely recognized as one of the most relevant pathogenic factors in ACLF, we think that restricting the selection of the studies to those specifically addressing ACLF, may decrease variability and other sources of heterogeneity in the effect of G-CSF. Finally, we did not have access to individual data, which could have allowed a detailed analysis of the characteristics of the patients who respond better to this therapy.

In summary, the results of this systematic review and meta-analysis suggest that the administration of G-CSF has no significant impact on survival in ACLF and, currently, cannot be recommended as a standard of care in this clinical setting. Further research aiming to define specific populations or refined therapeutic protocols could select better candidates to benefit from this immune-targeted approach in future clinical trials.

FundingAgustín Albillos is supported by grants from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (SAF 2017-86343-R) and Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI20/01302). CIBEREHD is funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III with grants co-financed by the European Development Regional Fund “A way to achieve Europe”EDRF).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.