The recognition and treatment of intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome are matters of controversy. The symptoms that have guided the search for the disorder suffer from lack of specificity, especially in the absence of well-defined predisposing factors. The accuracy of diagnostic procedures has been questioned and the proposed therapies achieve generally low effectiveness figures, with large differences between available studies. It is also unknown whether the normalization of tests is really a guarantee of cure.

Within this framework of uncertainty, and in order to contribute to the guidance and homogenization of medical practice, a group of experts from the AEG and ASENEM have formulated the key questions on the management of this pathology and have provided answers to them, in accordance with the available scientific evidence. In addition, they have drawn up statements based on the conclusions of the review and have voted on them individually to reflect the degree of consensus for each statement.

La identificación y el tratamiento del síndrome de sobrecrecimiento bacteriano intestinal son materias sujetas a controversia. Los síntomas que han orientado la búsqueda del trastorno adolecen de falta de especificidad, especialmente en ausencia de factores predisponentes bien definidos. La precisión de los procedimientos diagnósticos ha sido cuestionada y las terapias propuestas alcanzan cifras de efectividad en general bajas, con grandes diferencias entre los estudios disponibles. También se desconoce si la normalización de los test es realmente garantía de curación.

En este marco de incertidumbre, y con la intención de contribuir a orientar y a homogeneizar la praxis médica, un grupo de expertos de la AEG y la ASENEM han formulado las preguntas fundamentales sobre el manejo de la patología y les han dado respuesta, de acuerdo a la evidencia científica disponible. Además, han elaborado declaraciones basadas en las conclusiones de la revisión realizada, y las han sometido a votación individual para reflejar el grado de consenso correspondiente a cada una de las mismas.

The human intestinal microbiota is made up of more than 1000 microbial species, including representatives of the Bacteria, Archaea and Eukarya domains. They reach their greatest proliferation in the colon, with approximately 1011–1012 colony-forming units per millilitre (CFU/mL), while their numbers decrease in other segments of the gastrointestinal tract, to a greater extent the more proximal the section analysed, with the exception of the oral cavity, which can host up to 109 CFU/mL.1,2

The concept of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, better known by its acronym, SIBO, refers to the increase in the bacterial load that colonises the small intestine and to variations in its taxonomic composition, with a particular prominence of anaerobes, which can cause certain symptoms and lab test abnormalities. Seeking greater specificity in the definition, it was initially agreed to define SIBO as the detection of more than 105 CFU/mL from jejunal aspirate.3 This figure was calculated based on findings in series of patients with postoperative anatomical changes. Subsequently, the North American consensus determined that the cut-off point should be modified to 103 CFU/mL from duodenal or jejunal aspirate cultured on MacConkey agar.4,5 More recently, the condition has been added that a coliform-dominant composition (common colonisers of the large intestine) should support the diagnosis.6–8

These numerical figures are subject to debate because it is known that, on the one hand, the duodenum generally contains a smaller quantity of bacteria than the jejunum, and on the other, the taxonomy of both is dynamic, adapting quickly to different situations, such as bowel disease or dietary changes.1 It has been found that asymptomatic subjects who consume a large amount of fibre in their diet can achieve a bacterial proliferation of up to 105 CFU/mL.9

Advances in our understanding of the intestinal microbiome, as well as its metabolic pathways, have meant that the paradigm has evolved, from an initial exclusively quantitative concept (overgrowth) to a vision that also considers qualitative changes (dysbiosis), thus combining modifications in microbial density with others related to its composition and the products generated during metabolism. This approach also allows the diagnosis of the disorder to be addressed from other perspectives, and raises the possibility of applying tests that provide measures of the products of microbial physiology. In any case, intestinal dysbiosis does not always translate into the development of symptoms and disease, so the two concepts, SIBO and dysbiosis, cannot be considered synonymous.10

Some non-invasive diagnostic tests have detected cases, with different symptoms, in which the overgrowth is fundamentally based on the proliferation of strict anaerobic microorganisms of the methanogenic archaea type (predominantly Methanobrevibacter smithii). This has given rise to a subclassification of SIBO, known as intestinal methanogenic overgrowth (IMO).2 Referring to another similar phenomenon, although excluded from the formal concept of SIBO, it has been suggested that some gastrointestinal symptoms could be explained by the overgrowth of Candida-type fungi, known as Small Intestinal Fungal Overgrowth (SIFO). However, the diagnosis has not been standardised and it frequently leads to unnecessary therapeutic decisions. In fact, the fungus is a common coloniser of the intestine and its mere presence in stool does not signify disease.

The purpose of this document is to review the scientific evidence on the concept, diagnosis and treatment of SIBO, focusing primarily on gastrointestinal involvement. Our aim with this material was to answer the most frequent questions that healthcare professionals have in view of the growing interest in this subject, and which is accompanied by an increasing, sometimes misguided, social demand for medical care related to this disorder. A secondary aim was to standardise the measurements that should be applied in clinical practice to bring them in line with current knowledge.

MethodsA panel of experts in neurogastroenterology was selected from among the members of the scientific societies Asociación Española de Gastroenterología (AEG) [Spanish Association of Gastroenterology] and Asociación Española de Neurogastroenterología y Motilidad (ASENEM) [Spanish Association of Neurogastroenterology and Motility]. The base text was written by the first three authors of the document (J. Alcedo, F. Estremera-Arévalo and J. Cobián), who formulated and answered the questions posed based on an individual review of the scientific evidence. Subsequently, a first draft was sent to all the authors (a total of 12 specialist physicians), who conducted an initial review and proposed the changes they considered appropriate in each section. These were added to the document, which was then sent back to all the authors for final approval.

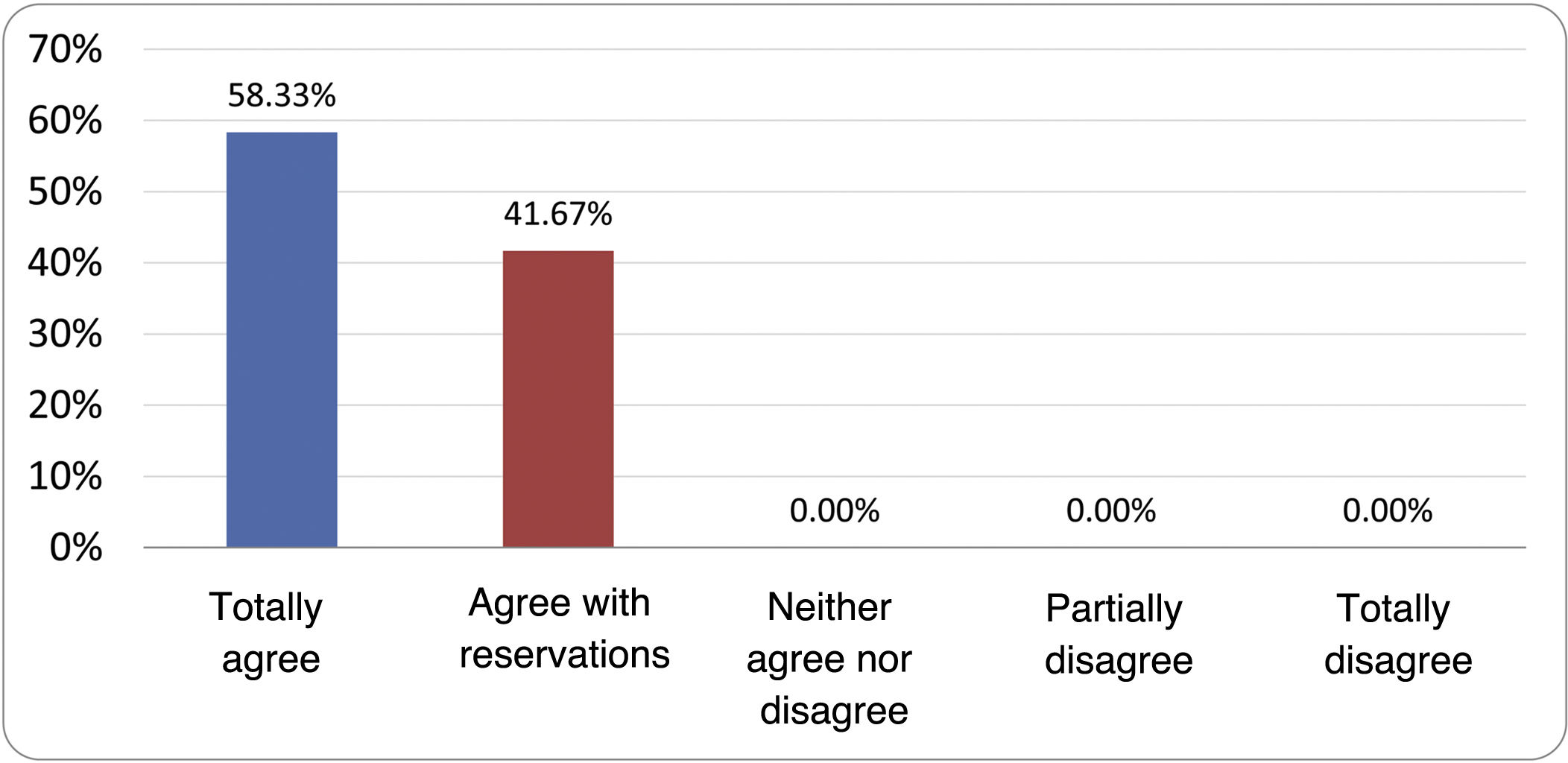

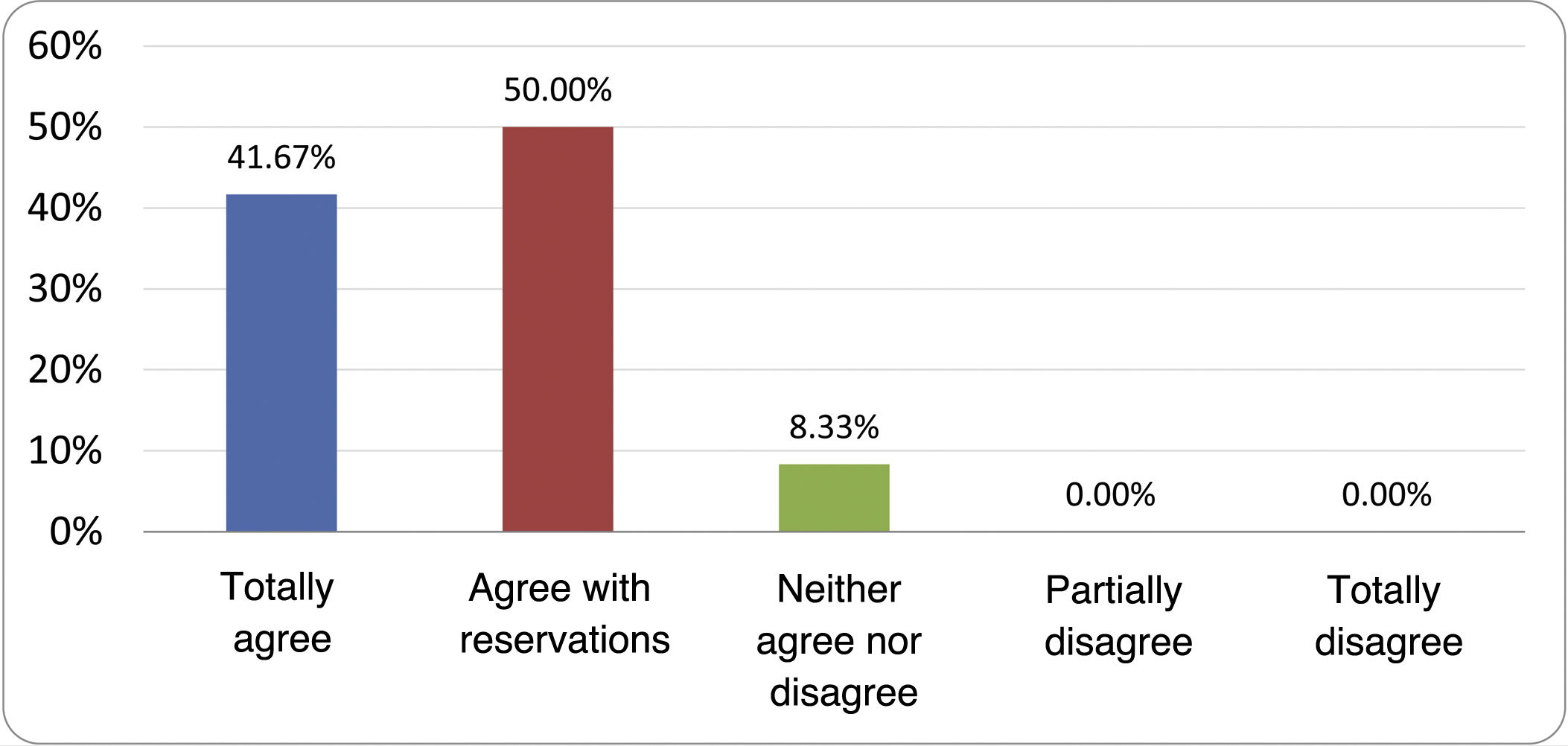

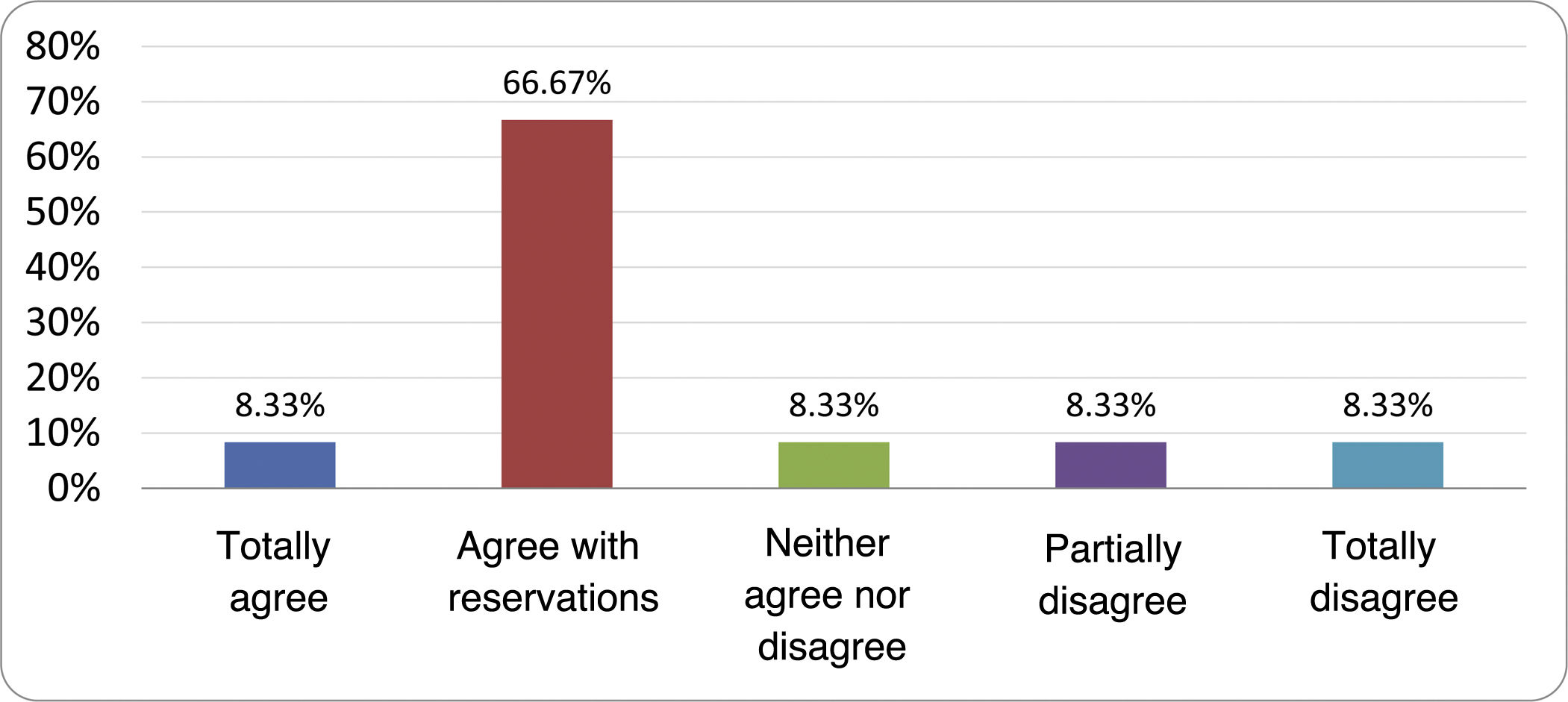

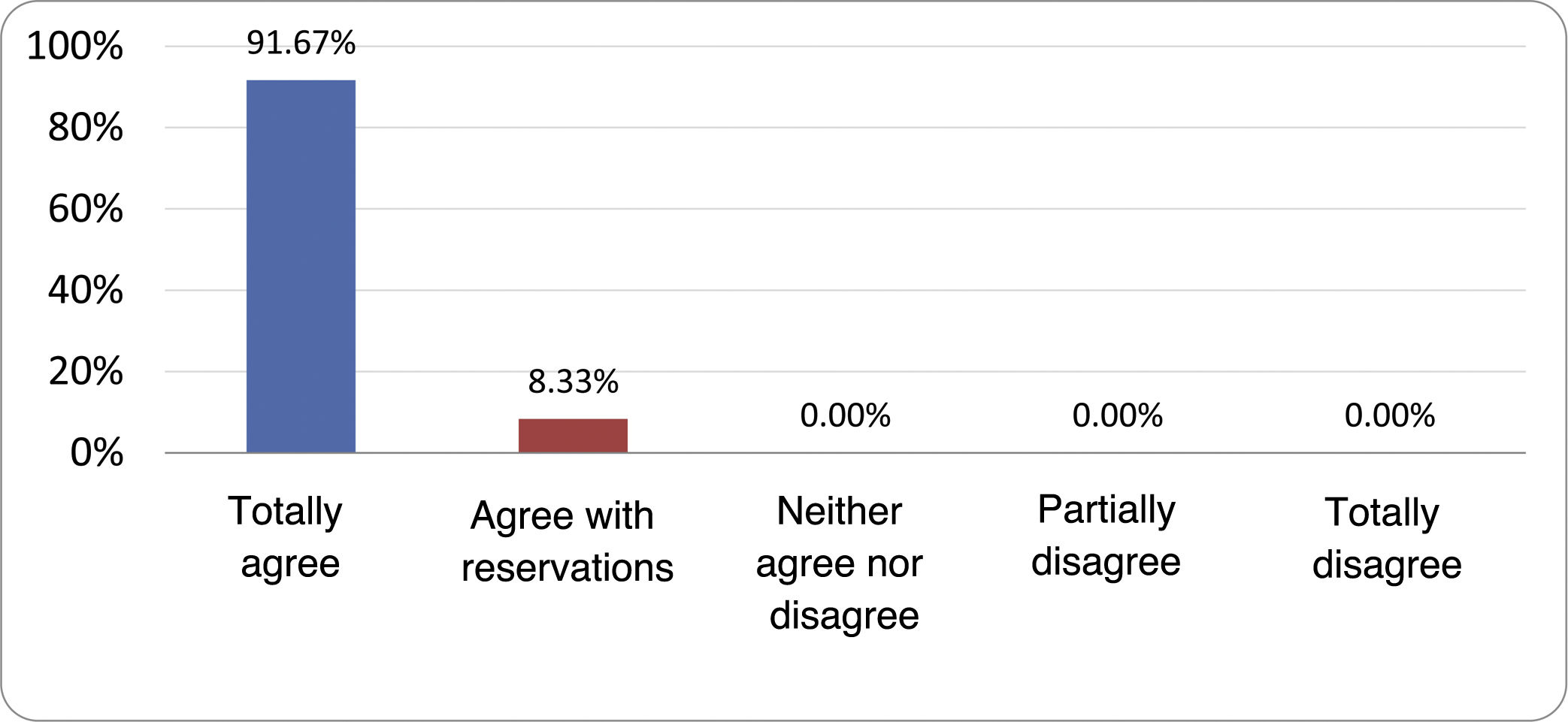

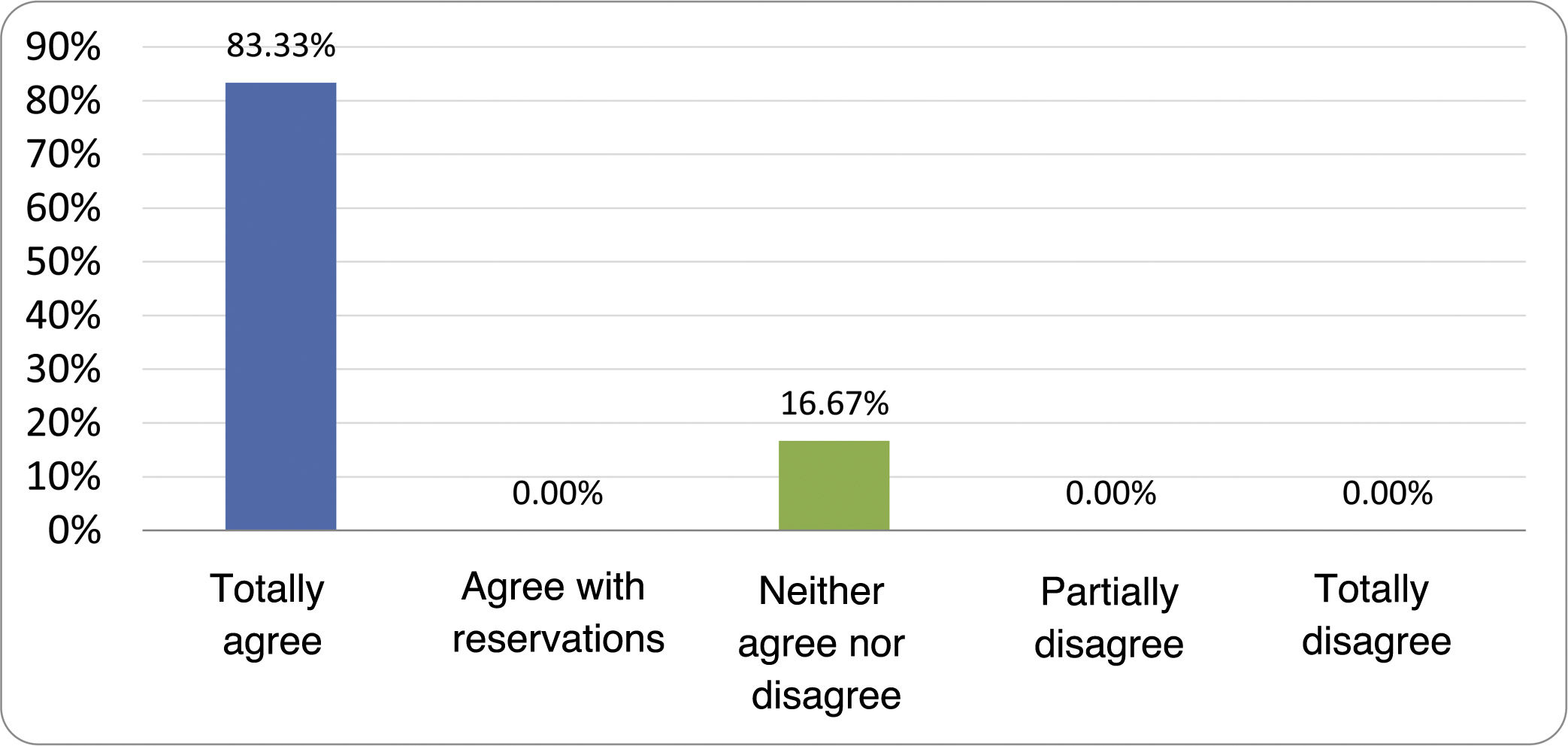

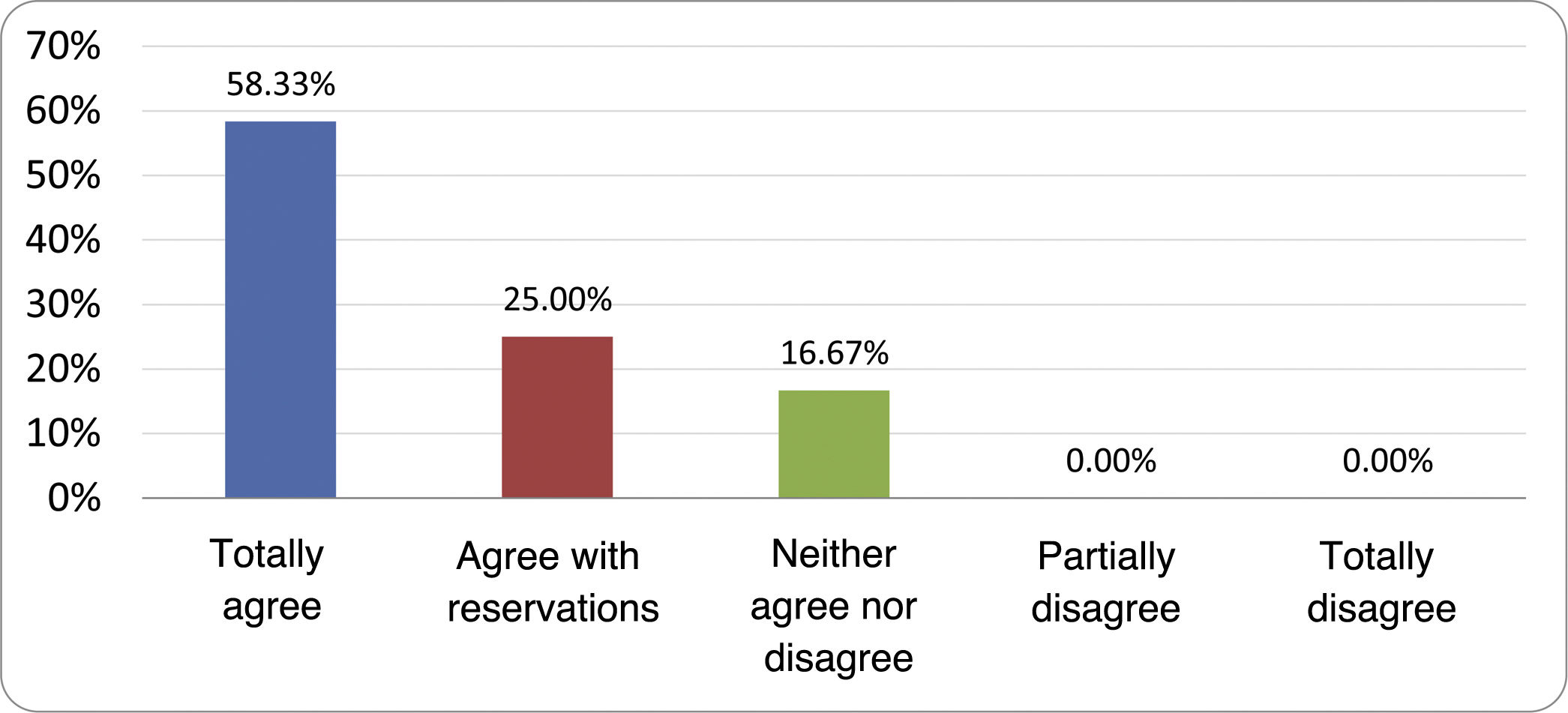

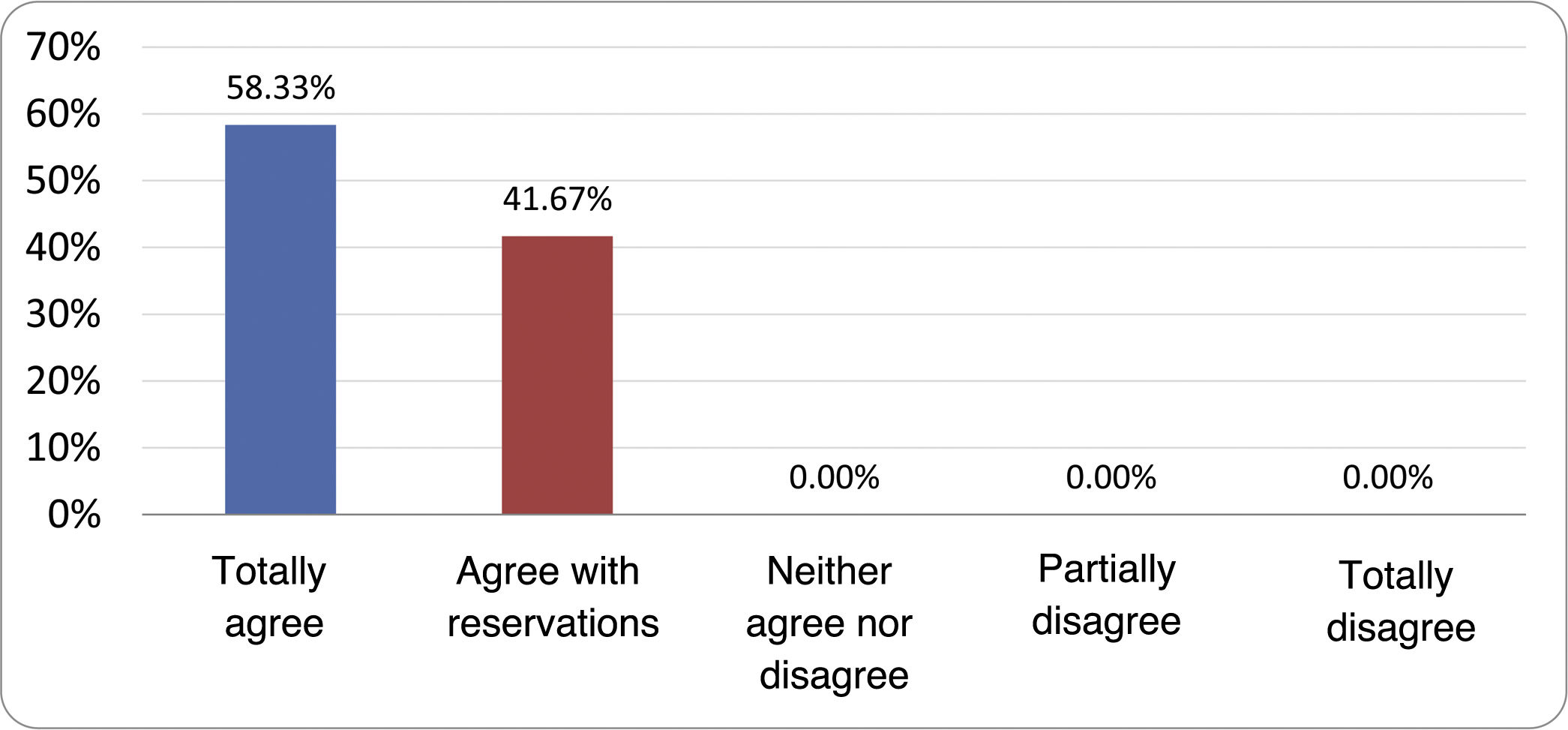

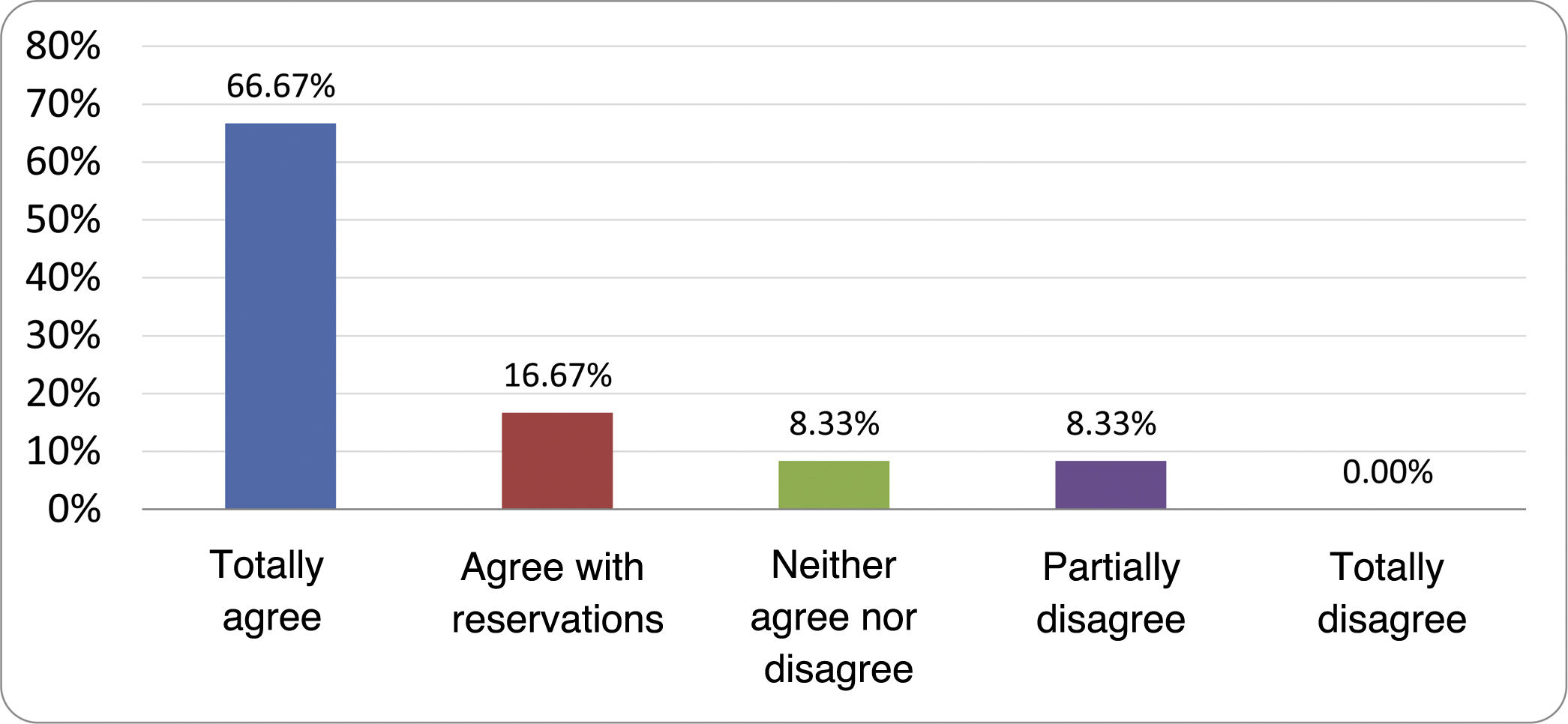

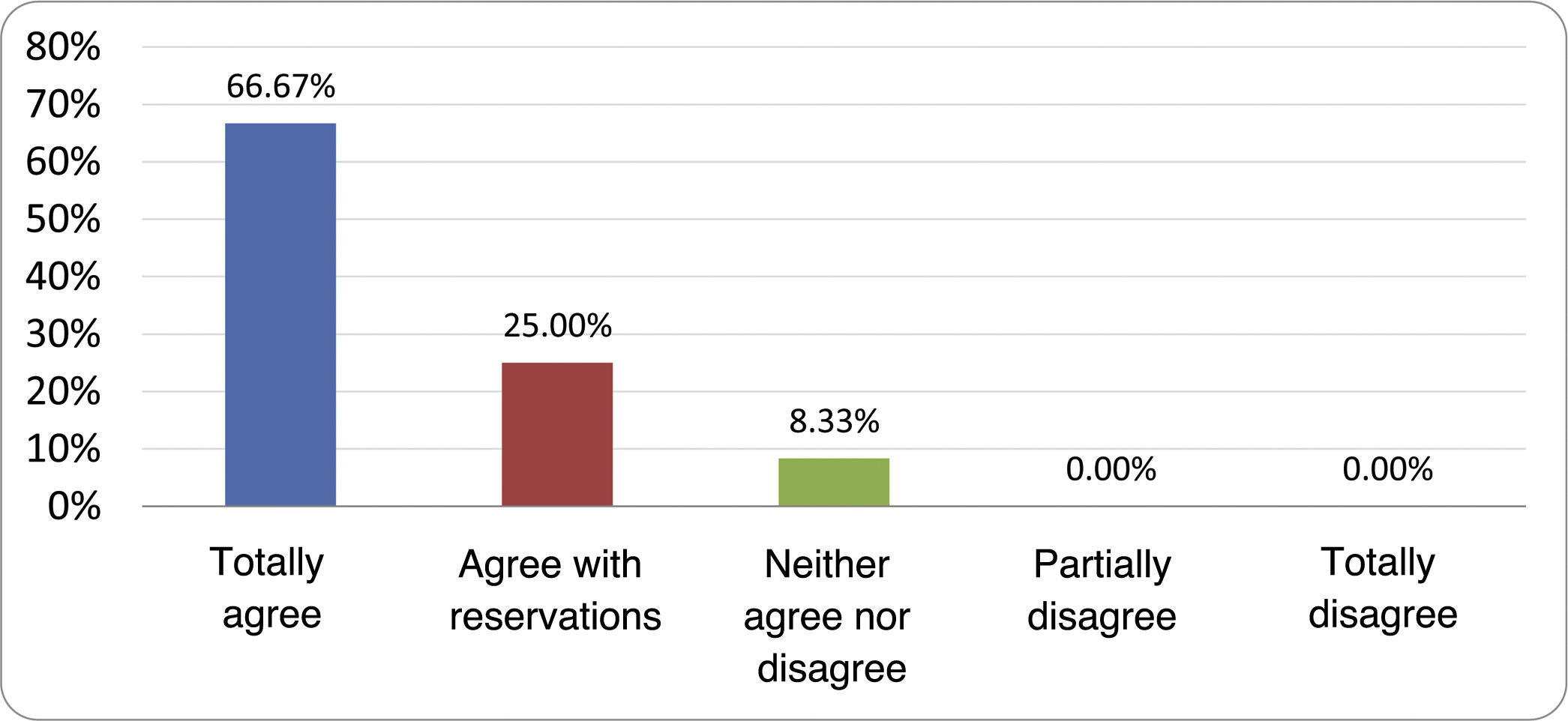

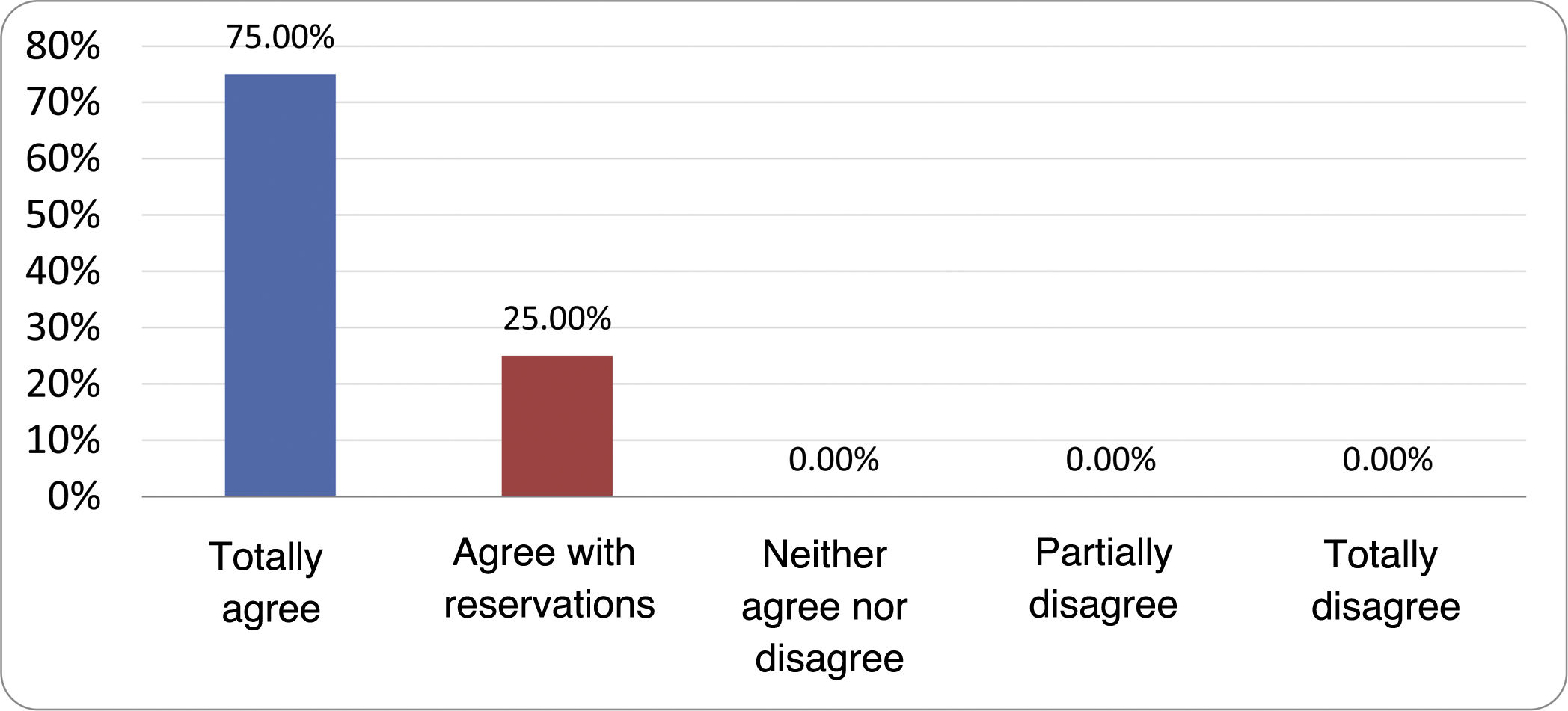

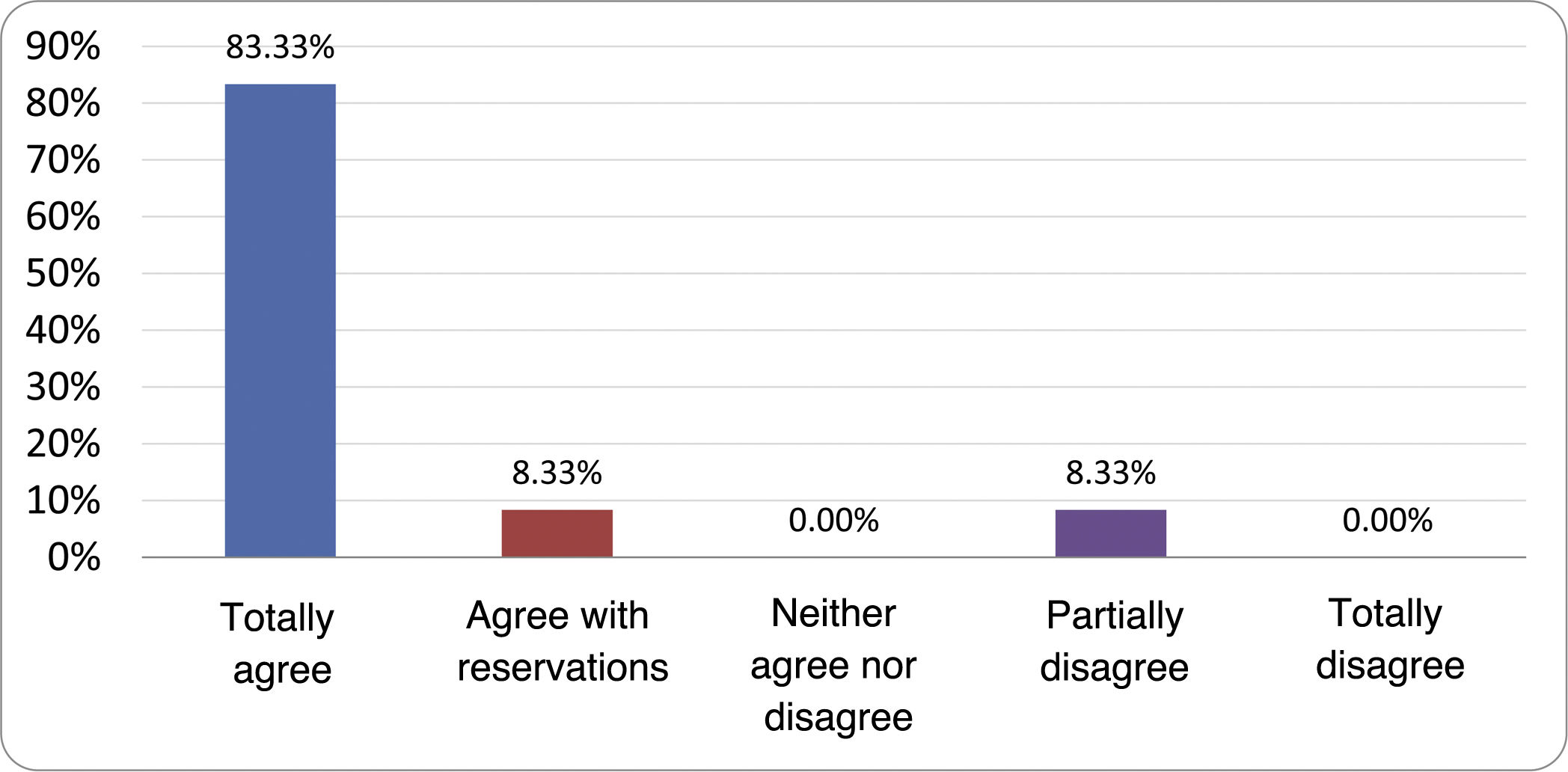

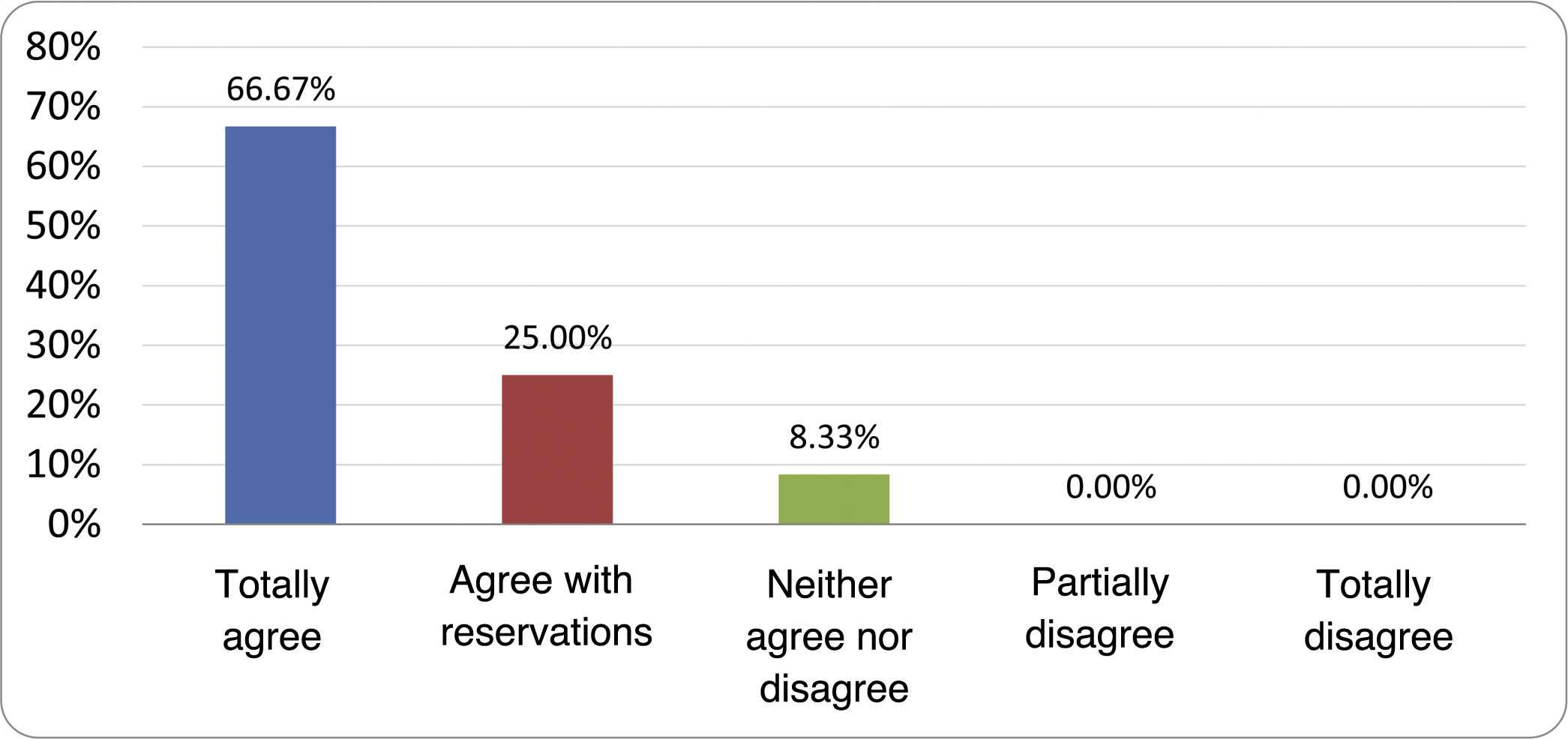

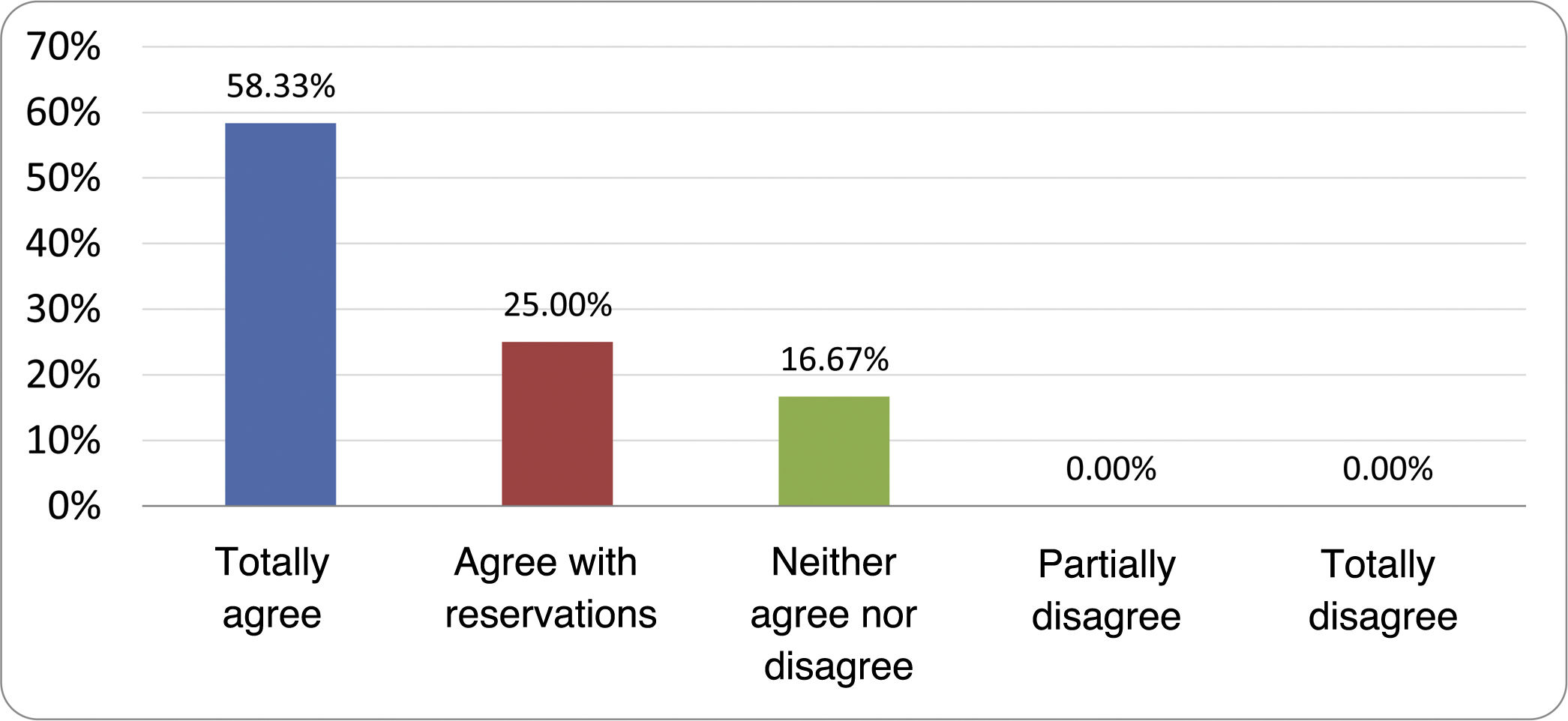

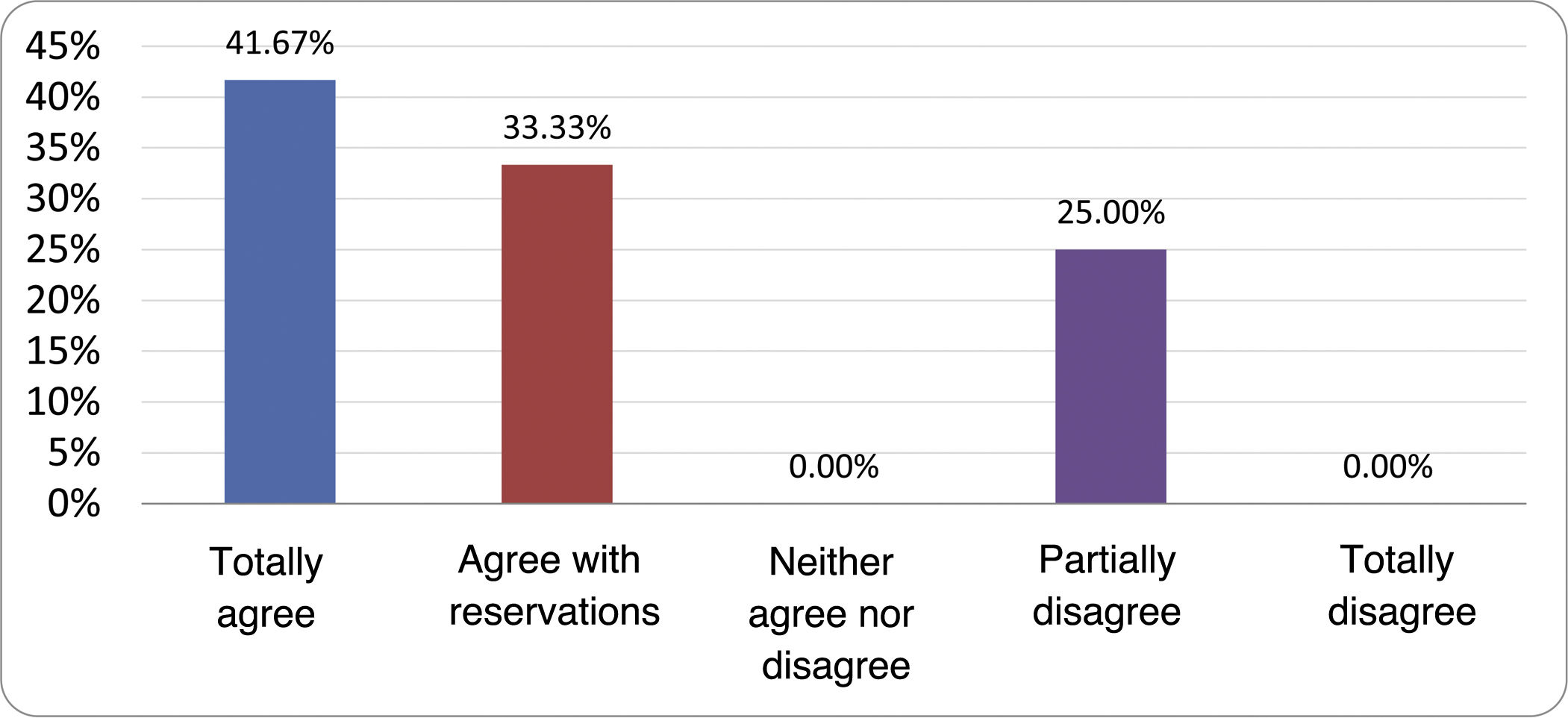

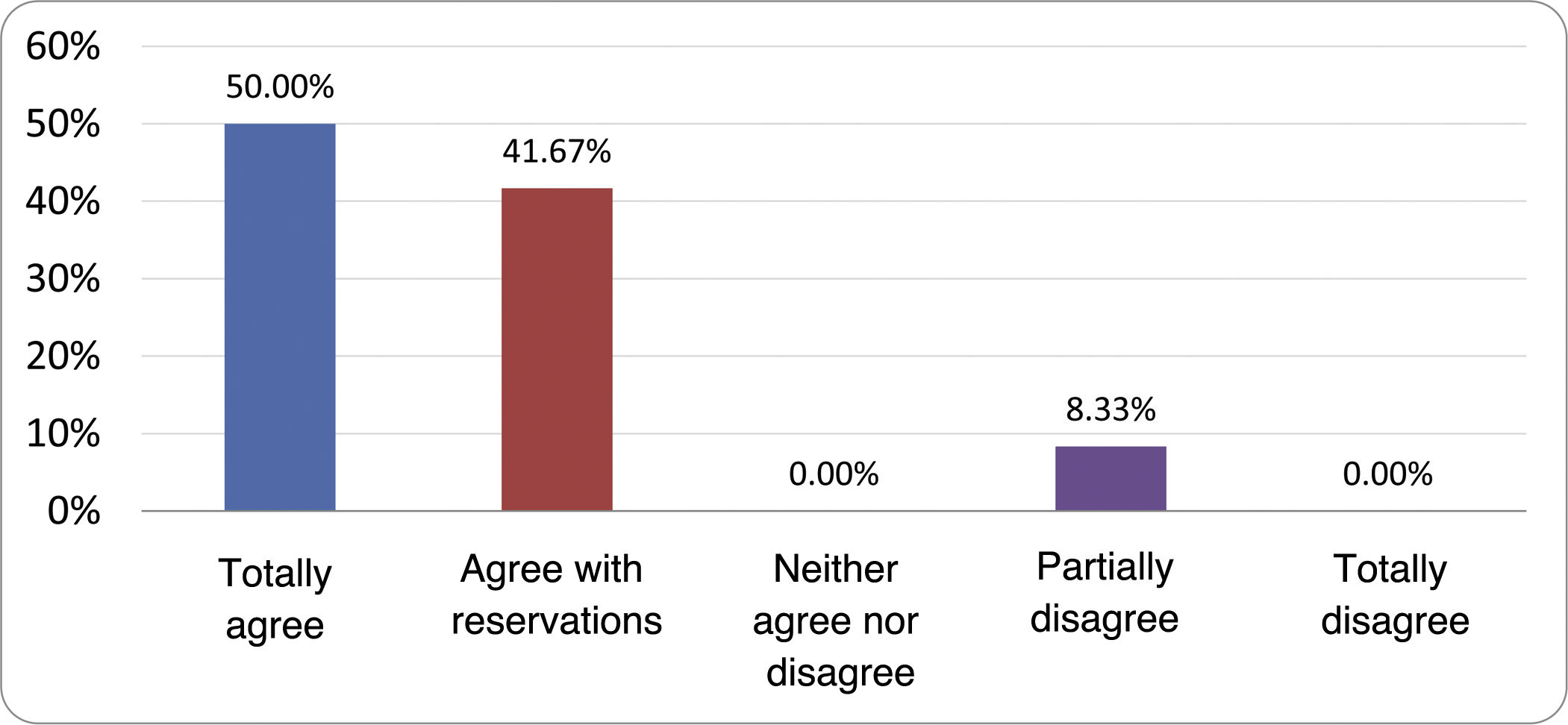

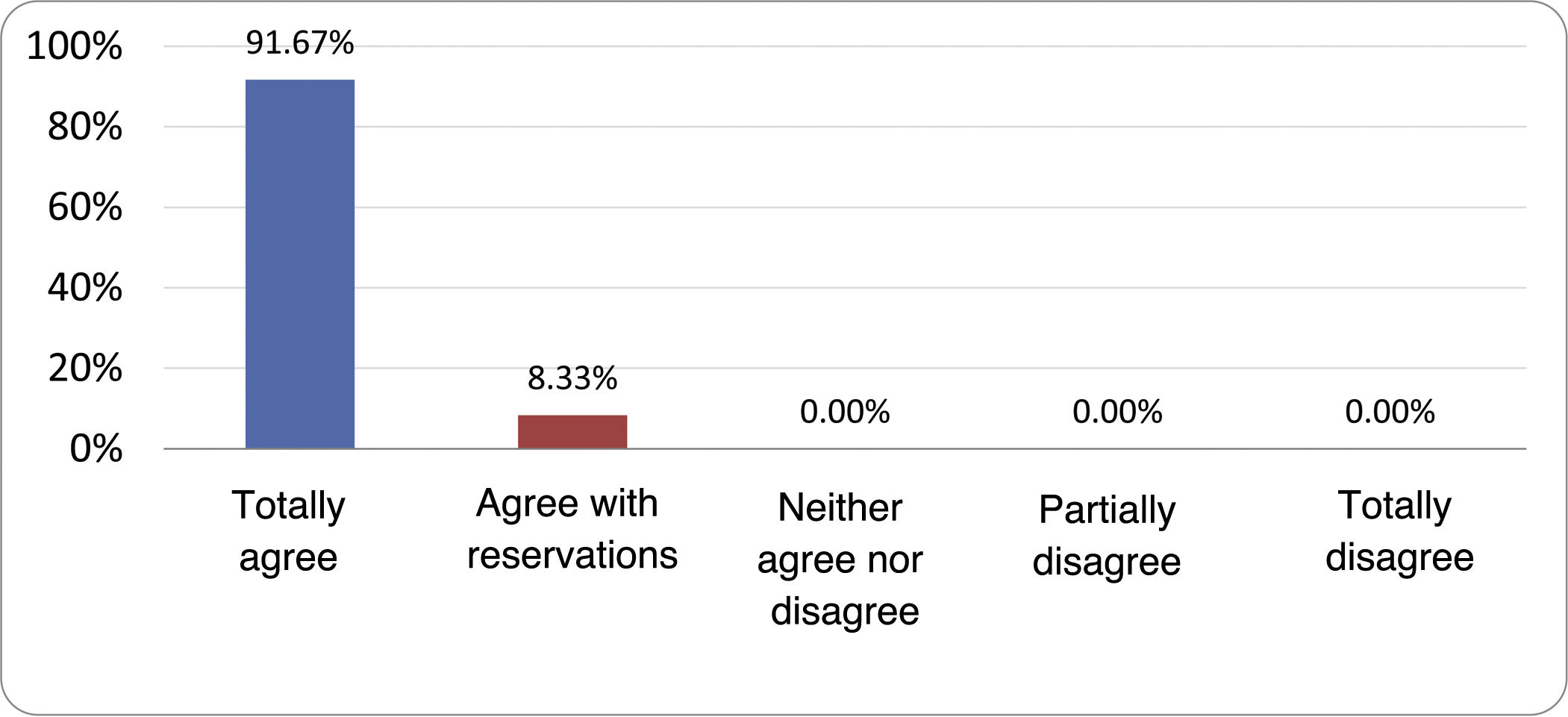

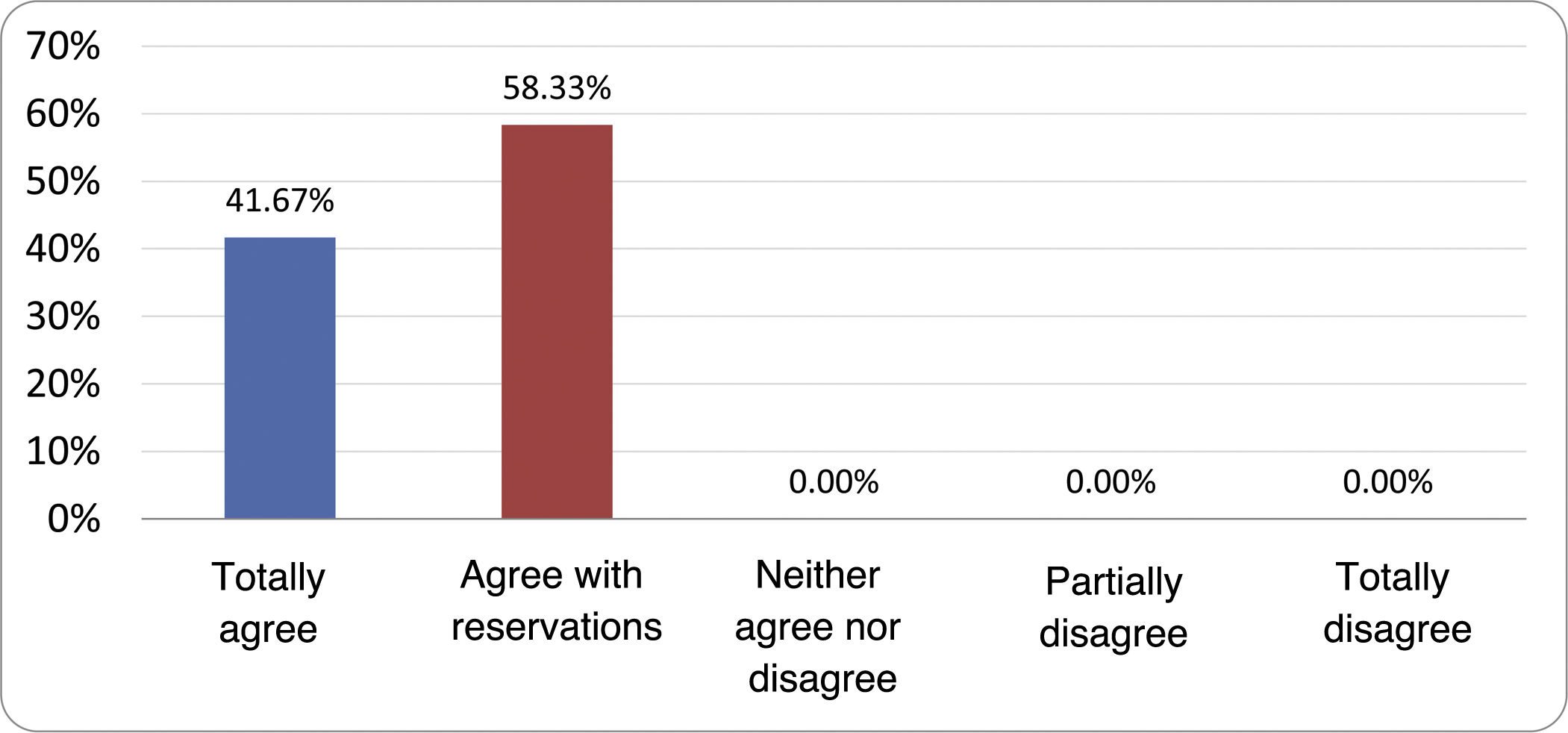

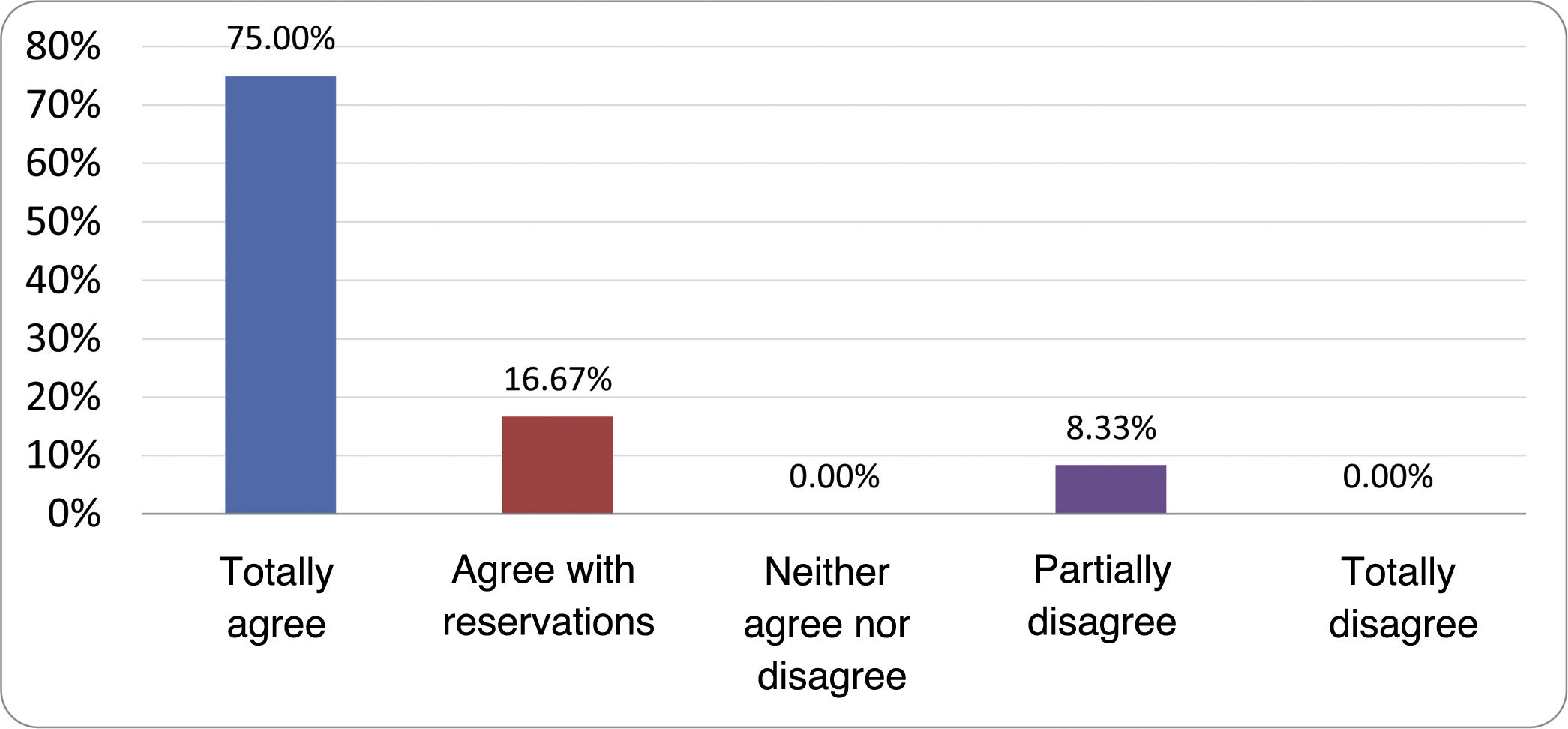

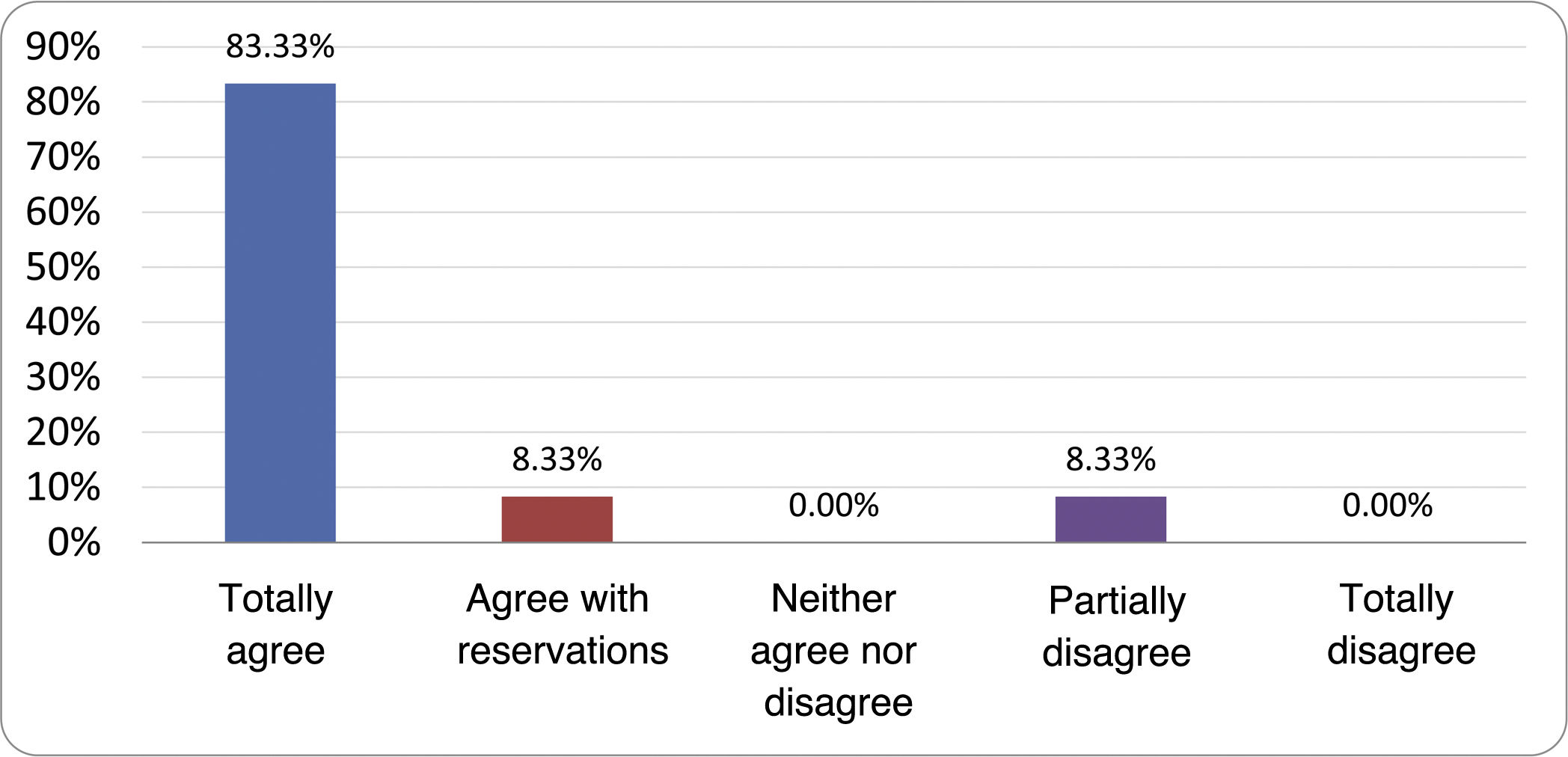

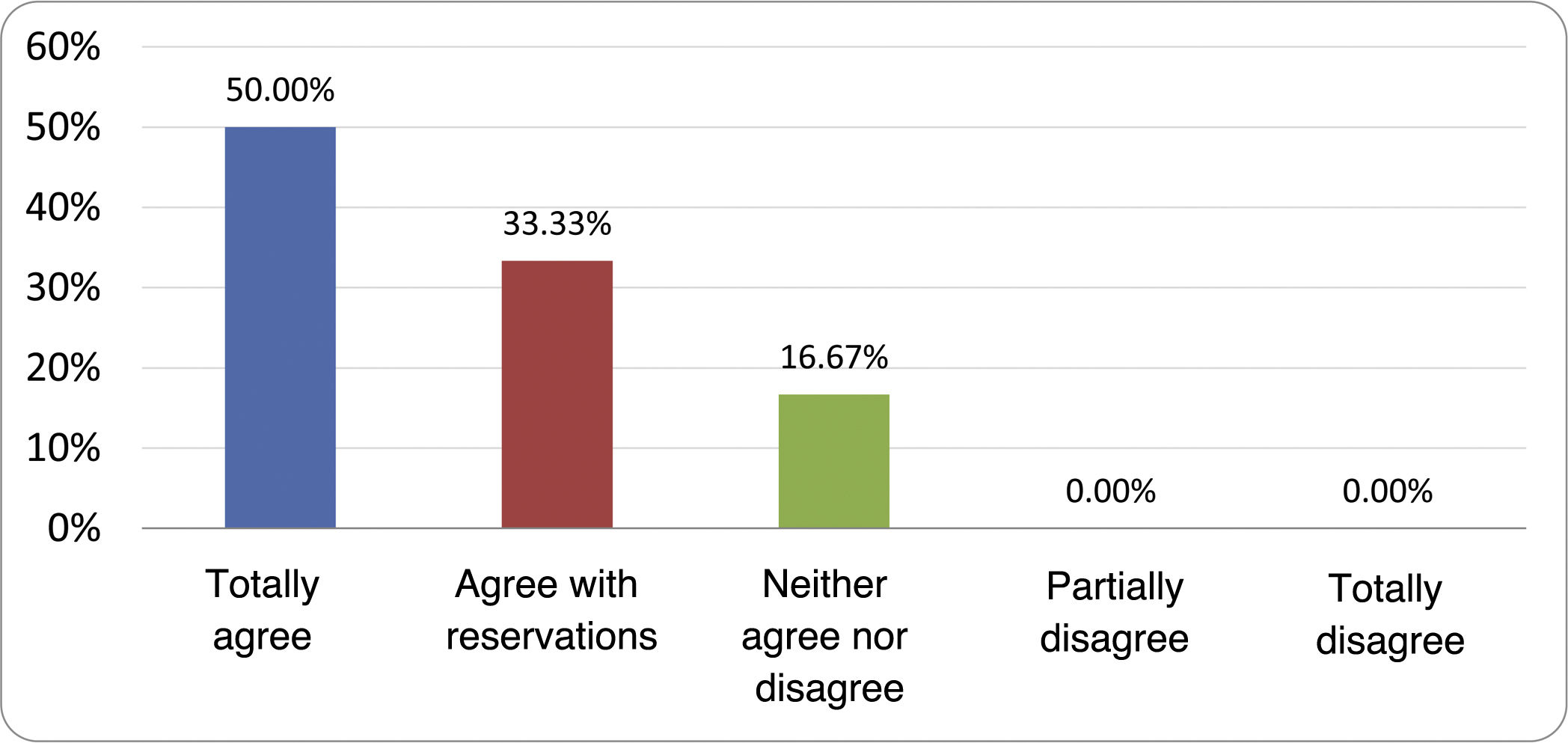

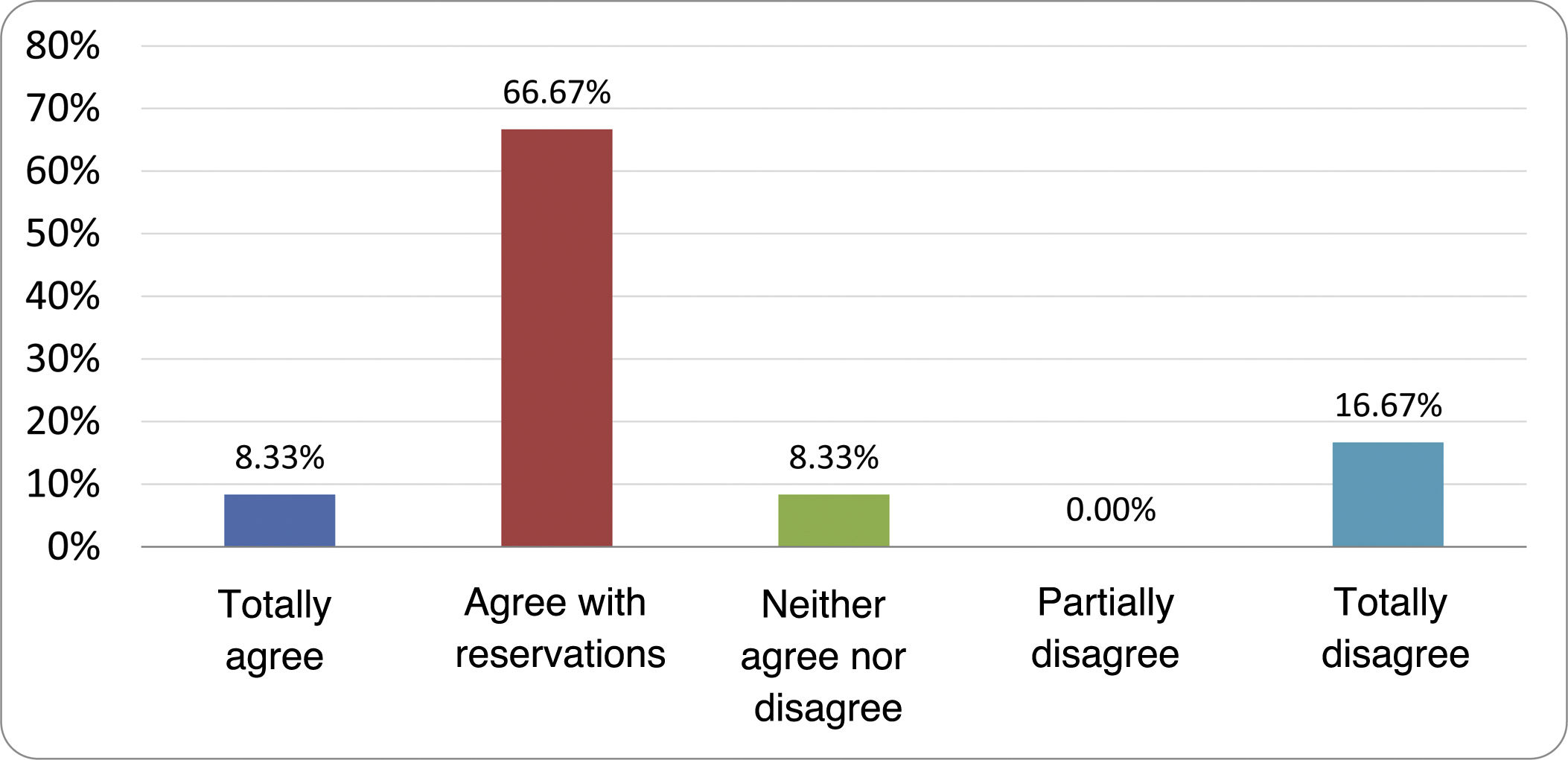

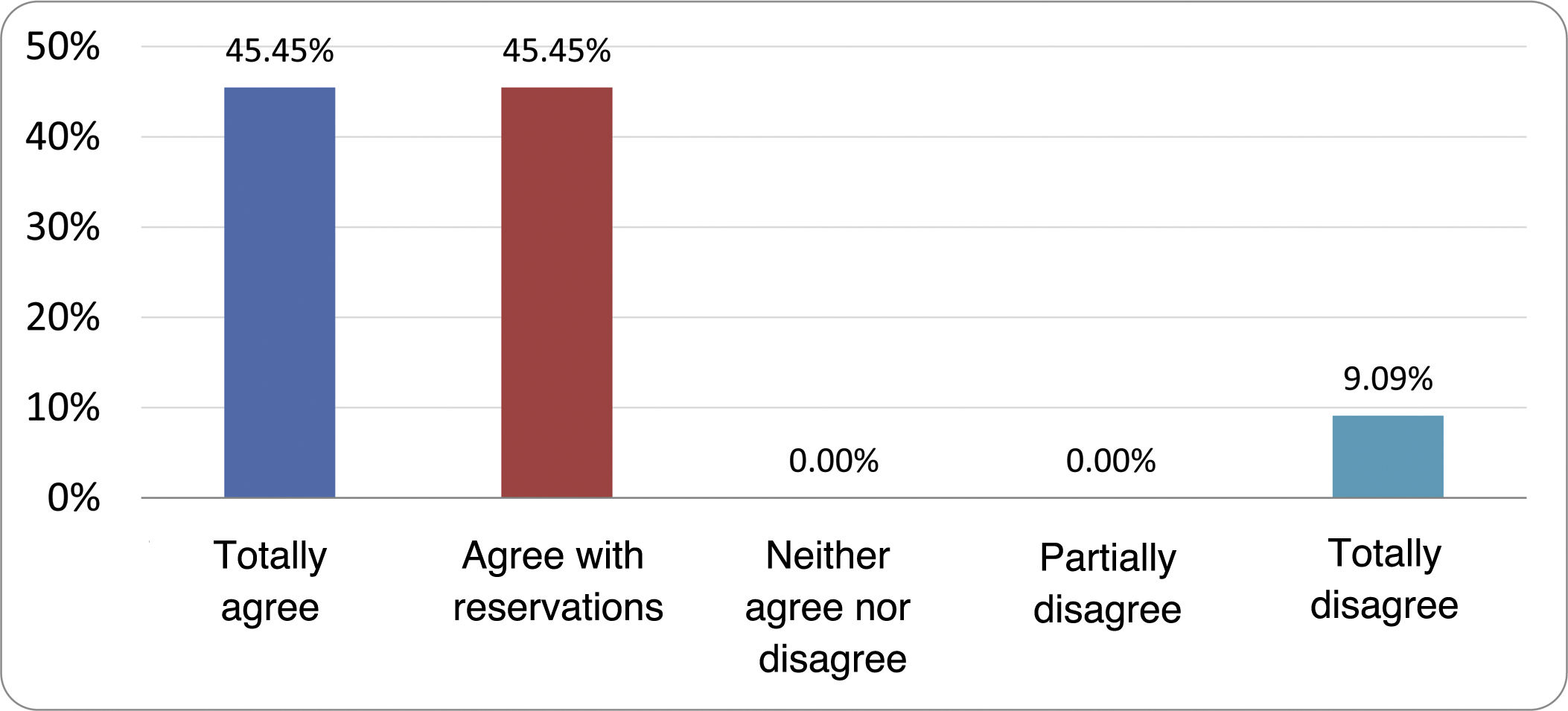

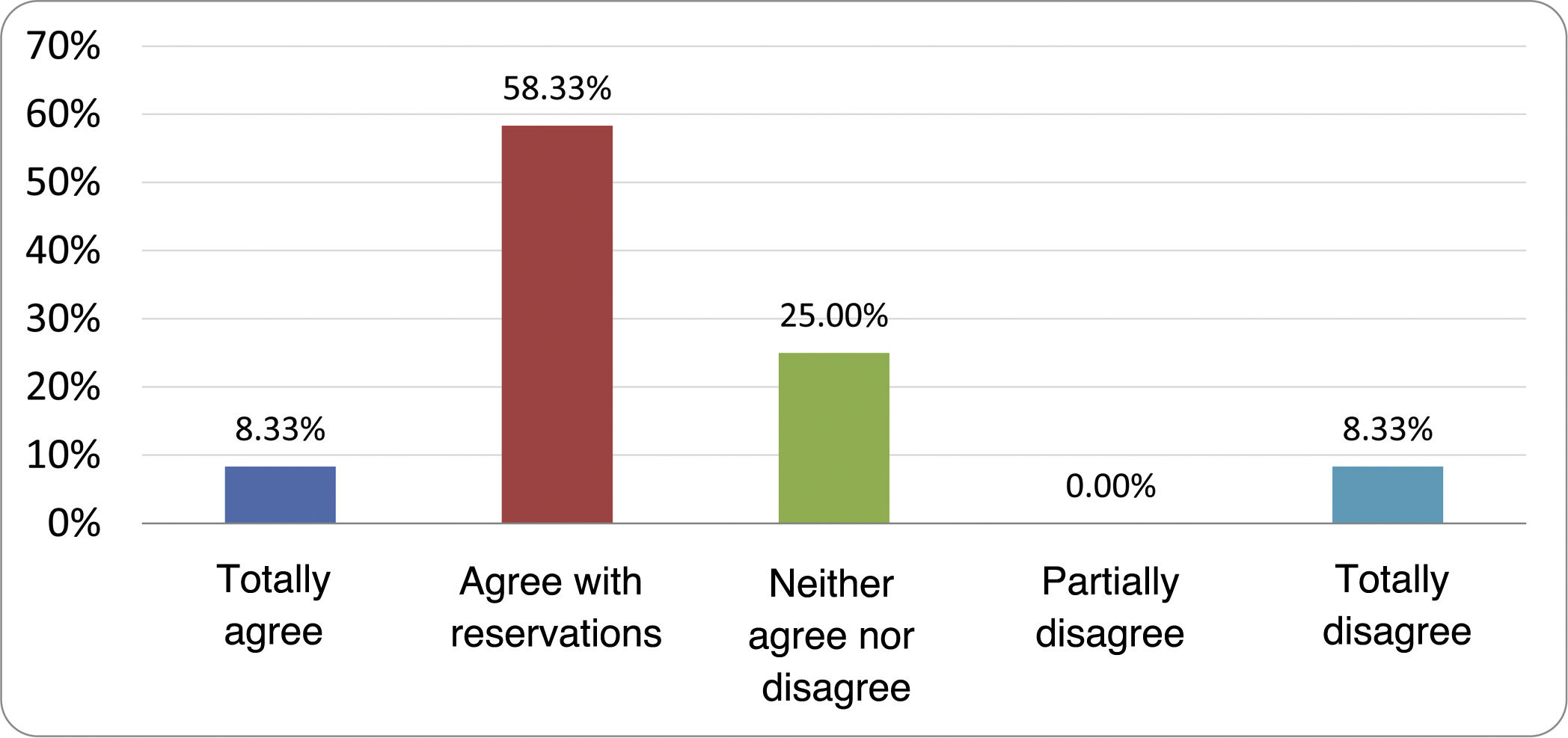

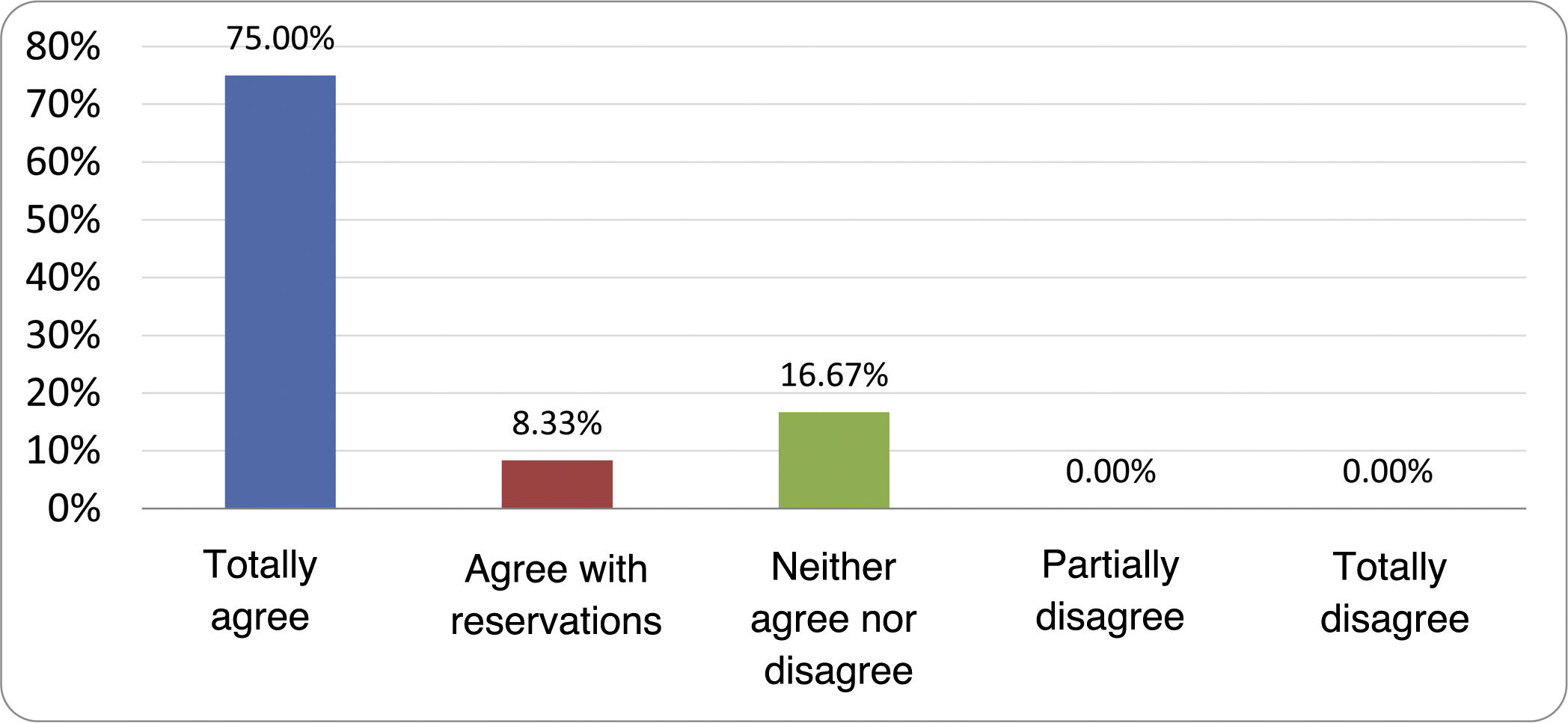

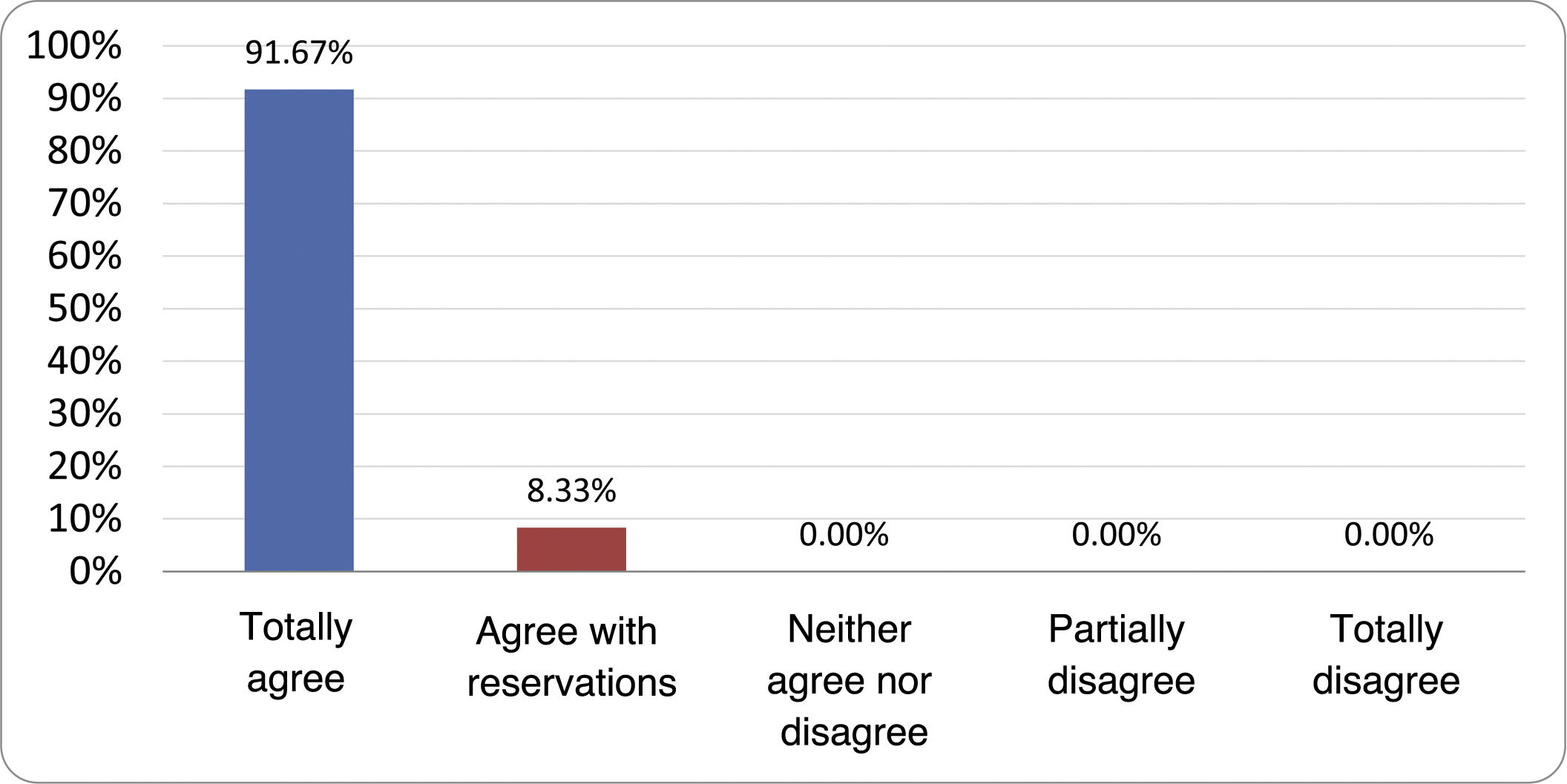

Based on the conclusions obtained, 25 statements were prepared and distributed by email among the panel of authors, so that each could express their degree of agreement or disagreement with them, based on a five-point Likert scale: 1) totally agree; 2) agree with reservations; 3) neither agree nor disagree; 4) partially disagree; and 5) totally disagree. A statement was considered accepted if the sum of the percentages of total agreement and agreement with reservations exceeded 80% (scores 1 and 2 on the scale) and the disagreement was less than 10% (scores 4 and 5 on the scale). In the remaining cases it was considered that there was not sufficient agreement to accept the statement as consensual. The percentages assigned to each score on the scale for each of the statements was also recorded.

What are the symptoms of intestinal bacterial overgrowth and when should it be suspected?The European Guidelines published in 2022, for the indication of hydrogen (H2) and methane (CH4) breath tests (consensus of the European Association for Gastroenterology, Endoscopy & Nutrition [EAGEN], the European Society for Neurogastroenterology and Motility [ESNM] and the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition [ESPGHAN]) propose that, even in the absence of an absolute consensus for the interpretation of the results, and until a true diagnostic gold standard for SIBO is available, testing should be considered in patients with abdominal bloating, pain or discomfort, flatulence and/or signs of malabsorption, once other diagnoses have been ruled out using endoscopic or imaging techniques, and especially if there are predisposing factors.11 The symptom spectrum has also been established to range from nonspecific symptoms of functional appearance and asymptomatic fatty liver disease, to situations of severe malabsorption that lead to vitamin deficiencies (B12, D, A and E), hypocalcaemia, iron deficiency anaemia, severe diarrhoea (with steatorrhoea and/or creatorrhoea) and weight loss.

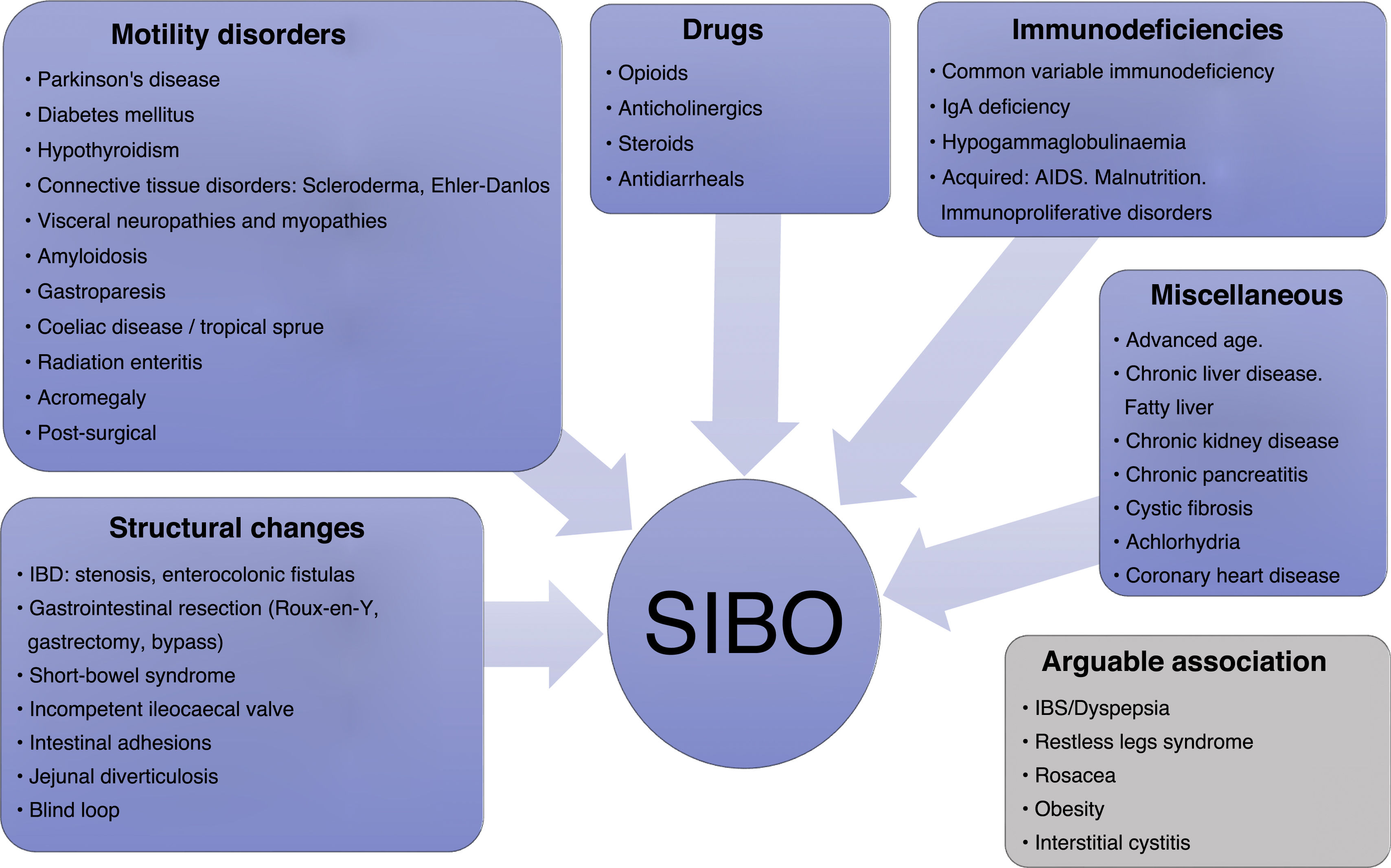

The predisposing factors referred to in the aforementioned guidelines are also multiple and can in turn determine the type of bacteria that proliferate. Biological factors such as being female or advanced age have been implicated, but above all anatomical and structural intestinal abnormalities, such as postoperative changes, blind loops, stricturing and fistulas or jejunal diverticulosis; severe motility disorders (severe connective tissue diseases, amyloidosis and Parkinson's disease); endocrine disorders and advanced metabolic disorders (achlorhydria, hypothyroidism and diabetes mellitus); various drugs; and a miscellany consisting of conditions such as rosacea, immunodeficiencies, inflammatory bowel disease, coeliac disease, radiation enteritis, chronic pancreatitis, severe liver or kidney disease and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), with a higher risk in the diarrhoea-predominant form (Fig. 1).11–14

However, the symptoms that usually lead to clinical evaluation for possible SIBO have weak or even no predictive value for diagnosis.15 In fact, while abdominal bloating and/or its objective translation, distension, are the symptoms traditionally considered as cardinal in SIBO, it is actually diarrhoea which has a more consistent association.6 It should also be borne in mind that clinical manifestations differ between the two types of SIBO described, one consisting of colonic bacteria (coliforms) and the other of oropharyngeal and respiratory bacteria.16 It is also worth mentioning that constipation and a low incidence of vitamin B12 deficiency are the basic clinical characteristics in patients with IMO.17

Another factor that influences the low correlation between symptoms and a diagnosis of SIBO is the variability in the diagnostic criteria applied. On the one hand are studies that conclude that the culture-based diagnosis of SIBO is not associated with symptoms such as diarrhoea, distension and abdominal pain. On the other, however, changes in microbiome composition do appear to discriminate symptomatic from asymptomatic subjects, and even reduced diversity, secondary to eating a Western diet (low in fibre, with 50% carbohydrates, 35% fat and 15% protein), predicts the onset of abdominal pain and bloating.9 A recent study only found an association between specific strains of the genera Escherichia and Klebsiella (both of which increase in relative abundance in SIBO) and symptoms of abdominal pain, diarrhoea and bloating.18 All of this suggests that symptoms are a poor predictor of SIBO, although it could be associated with certain changes in the intestinal microbiological profile, in line with that found in patients with IBS or flatulence.19–22

In 2020, the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Clinical Guideline23 suggested (with a very low level of evidence) investigating SIBO only when there are compatible symptoms and very specific predisposing factors, such as severe intestinal motility disorders, luminal abdominal surgery, IBS or constipation. With regard to the use of proton pump inhibitors (PPI), the data in the literature are contradictory. The first reports pointed to a moderate increase in the risk of SIBO in users of these drugs.24 However, the most recent meta-analysis of case-control studies, including various diagnostic methods, has not been able to corroborate the risk attributed to the use of PPI (odds ratio [OR] 0.8; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.5–1.5),25 so the aforementioned ACG guideline does not consider the use of PPI to justify performing diagnostic tests. Subsequent to that guideline, one study concluded that PPI use induces dysbiosis in duodenal aspirate, with an increase in the relative abundance of the Campylobacteraceae (×3.1) and Bifidobacteriaceae (×2.9) families, and a relative decrease in Clostridiaceae (×88.2), but without causing the frequency of SIBO to increase.26

More recently, the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) published a comprehensive review on the management of abdominal bloating and distension, with the express recommendation in its management algorithm to limit breath testing exclusively to patients with clear predisposing factors and/or severe symptoms.27 Given this criterion, it should be interpreted that the mere existence of constipation, or compliance with the criteria for IBS, would not in itself be a justification for testing for SIBO.

Response. SIBO is a syndrome with heterogeneous aetiopathogenesis and nonspecific presentation. Diagnostic suspicion may be established when the symptoms that form part of its clinical spectrum manifest with certain anatomical, metabolic or intestinal motility-related pathogenic factors. Bloating and abdominal distension are not symptoms that alone can predict SIBO, and in the absence of specific predisposing factors and severe symptoms, it is accepted that the decision to perform tests to confirm or rule out SIBO would not be justified.

What is the diagnostic validity of the diagnostic tests for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth?Bowel aspirate culture has been considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of SIBO. However, as mentioned in the Introduction section, the cut-off point for the number of CFU considered pathological remains subject to debate. Furthermore, it is accepted that the culture can give false positives due to contamination by oral microbiota (up to 20%), and also false negatives due to the failure to detect anaerobes when air is blown during sample collection, because samples are only obtained from proximal segments of the intestine and because only 30% of the bacteria can be cultured.5

Gene sequencing methods make it possible to estimate the bacterial load and increase the number of taxa analysed compared to the capacity of conventional culture, as well as directly test for microorganisms in the intestinal mucosa. A study comparing the two techniques, jejunal aspirate culture and gene sequencing in aspirate and mucosa, concluded that culture did not appear to adequately reflect luminal microbial composition. Furthermore, the authors distinguished between the two types of SIBO (coliform vs upper respiratory and digestive tract) and observed different behaviour in the bacterial diversity indices.28 More recently, the results of a sequencing and culture study by Leite et al. provide a greater degree of certainty by concluding that above the cut-off point of 103 CFU/mL from duodenal aspirate, there is a significant association with the loss of microbial diversity and connectivity and with the relative abundance of coliforms.18

The choice of technique for obtaining tissue or aspirate samples for sequencing studies can also affect their results. Those obtained through endoscopy (biopsy or brushing) require prior cleansing of the colon, which alters the local microbiota, and they are at risk of contamination as they pass through the working channel, although attempts have been made to minimise this with devices such as the Brisbane Aseptic Biopsy Device (MTW, Wesel, Germany). However, in all cases where a biopsy is obtained, the sample is small and the yield does not seem to be superior to that obtained with intestinal fluid aspiration. For intestinal fluid aspiration, complex devices based on ingestible capsules with negative pressure or nasointestinal tubes have been used, which have not prevailed over conventional endoscopic aspiration or have simply not been marketed.29

The alternative to the study of intestinal aspiration and sequencing tests on tissue, less invasive and more economical, is the breath test with detection of exhaled H2, for which different substrates can be used, most commonly lactulose and glucose. The test requires specific and demanding preparation, which includes avoiding antibiotics for a period of more than four weeks, as well as prokinetics and laxatives in the days prior, following a low-carbohydrate diet, using medicinal mouthwash, fasting for eight to 12 h and not exercising or smoking during sample collection.3 Compliance with these requirements can be complex in practice, especially if the test is performed in an environment without the supervision of a healthcare professional trained in the procedure, which can undoubtedly affect the validity of the results.

A systematic review with meta-analysis reported very low diagnostic accuracy figures for tests with lactulose, as well as suboptimal figures for tests with glucose (Table 1).30 Yu et al.31 had taken scintigraphic measurements of orocaecal transit simultaneously with the administration of lactulose, finding that in 88% of the cases in which there was an increase in exhaled H2, more than 5% of the administered substrate had already reached the caecum. It remains uncertain, however, whether the passage of this amount of substrate to the caecum could be responsible for a false positive.

Accuracy of breath tests for diagnosing SIBO*.

| Diagnostic test | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Positive LR (95% CI) | Negative LR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose test (50−100 g) | 54.5% (48.2%−60.7%) | 83.2% (79.1%−86.9%) | 2.45 (1.51−3.97) | 0.60 (0.45−0.80) |

| Lactulose test (10−12 g) | 42% (31.6%−53.0%) | 70.6% (61.9%−78.4%) | 1.30 (0.77−2.22) | 0.79 (0.57−1.08) |

LR: likelihood ratio.30

In view of these data, most experts advise against using lactulose as a substrate (except in diabetic patients) and advocate using glucose instead only in those patients with clear predisposing factors and/or nutritional deficiencies consistent with SIBO and not explainable by another disorder. Even under these conditions, it is important to understand that the use of glucose is not exempt from false positives due to rapid transit and fermentation of the substrate in the colon. A study with scintigraphic monitoring of gastrointestinal transit concluded that false positives due to this phenomenon could be as high as 65% in patients with a history of upper gastrointestinal tract resection, compared to 13% in those who had not had surgery. The dose of glucose used also affects the result, and although there is no agreement between the most widely used in Europe (50 g) and the North American consensus recommendation (75 g), it has been shown that the use of high doses is associated with a high rate of false positives. To improve the accuracy of these tests, it has been suggested that a test that evaluates intestinal transit (scintigraphy or magnetic resonance imaging) should subsequently be performed in positive cases, especially if there is a history of gastrointestinal resection, to rule out that the increase in H2 coincides with passage to the colon, although this alternative would significantly increase the cost of the procedure.32,33

There are several mechanisms associated with false positive results in breath tests. The most common are the aforementioned accelerated intestinal transit, the ileocaecal reflex and the mobilisation of faecal matter during the test. It is estimated that up to 13% of breath tests with a positive result for SIBO can be attributed to accelerated intestinal transit and the substrate reaching the caecum, where it is fermented by the caecal microbiota. Another phenomenon associated with false positives is the passage of intestinal content retained in the ileum into the colon when ingesting the substrate, caused by a physiological gastroileal reflex. Lastly, it is important to remember that faecal matter contains gas bubbles in areas that are not always in contact with the colonic mucosa, especially in patients with constipation. During normal peristaltic movements, these bubbles can move and come into contact with the mucosa, falsifying the test result. In fact, some authors consider that constipation should be excluded from the indications dictated by the ACG23 for performing a diagnostic test for SIBO.33,34

It has been proposed that not only the measurement of H2, but also the measurement of CH4, as a metabolic product of the archaea domain, could be a marker of SIBO, subclassified as IMO, especially among patients with constipation. A recent study concluded that levels of this gas in the breath test were higher in patients with IBS with constipation, correlating with the abundance of methanogenic archaea in stool samples.35 Even an isolated fasting CH4 measurement above 10 parts per million (ppm) has been associated with constipation and meteorism, and an increase in the faecal load of M. smithii.36 However, consideration has to be given to the fact that regularly incorporating this variable into the diagnostic system involves introducing potential confounding factors. CH4 levels are highly variable in healthy subjects, increase with the ingestion of non-fermentable substrates, come mainly from microorganisms located in the colon, and in people with constipation, could be due to the metabolism of colonic content ingested several days before the breath test.33 Despite the above, the European and North American consensus maintains the recommendation to determine the levels of both gases, H2 and CH4, when performing a breath test, believing that this is the only way IMO can be diagnosed.

Determination of microbial load and diversity in stool has not been shown to be a good predictor of the microbial load and diversity in the intestinal mucosa,37–40 and although there are parallels in the detected taxonomy,41 research in stool samples is not considered a useful marker in the diagnosis of SIBO, even less so when it is known that the microbiota varies very significantly in load and variety depending on the section of the intestine analysed.8,42

With an emphasis on diagnosing changes in bacterial diversity and taxonomy rather than an increase in their total load, detection by various means of products of bacterial metabolism, such as volatile organic compounds (VOC), could be a promising diagnostic alternative. The processing and analysis of stool, urine, serum or even breath samples, using techniques such as gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry, ion mobility spectrometry, biosensors or electronic nose devices, could reflect, through the concentration and profile of VOC, many aspects of the metabolic phenomena that occur individually in the intestine. To date, promising results have been obtained for the objective of differentiating patients with diarrhoea-predominant IBS from those with inflammatory bowel disease, with areas under the curve above 0.90. However, the method is still not very precise when it comes to differentiating between patients with IBS and healthy subjects.43

Last of all, one future option may be the targeted detection of intestinal gases using wirelessly-controlled ingestible capsules, whose transit and sample collection are controlled. This would provide exclusive results from predetermined sections of the gastrointestinal tract. For the moment, the results have shown a good correlation with those of breath testing, and although it is expected that the performance of breast tests will improve, they are still in the development phase.44

Response. There are uncertainties with regard to diagnostic cut-off values when it comes to culture of intestinal aspirate, and although sequencing procedures add additional parameters that could improve validity, both are expensive and invasive methods, which greatly hinders their applicability in the clinic. The results of breath tests alone do not provide sufficient precision to establish a diagnosis and justify the initiation of treatments, so their use should be limited to situations in which there are well-defined predisposing factors that increase the pre-test probability. Measuring H2 and CH4 levels and using glucose substrate (50 g in Europe) is recommended under these circumstances, especially if it can be performed together with a test to measure intestinal transit. VOC analysis techniques and targeted wireless capsules are promising alternatives but have not yet been validated for the diagnosis of SIBO.

Do the available tests predict response to treatment?A study with lactulose reported that test positivity could predict response to rifaximin treatment in patients with diarrhoea-predominant IBS. Furthermore, patients with a positive test improved to a greater extent than those without (59.7% of those with a positive test vs 25.8% of patients with a negative baseline test), and those who tested negative after treatment had an immediate symptom response rate of 75.6%, compared to 48.4% overall.45 The same group had previously obtained similar results using neomycin as a treatment in patients with IBS of any clinical phenotype. Symptom improvement was seen in 11% of those receiving placebo, 36.7% of those who received neomycin and had a negative pre-treatment lactulose test, and 75% of those who took the antibiotic and had a positive baseline test.46

However, the first and most recent of the studies mentioned was later challenged by experts and some basic aspects of its methodology were questioned.47 One of the main criticisms was based on the fact that the samples were obtained by the patient at home, without specialised control and without being able to verify compliance with the formal requirements demanded by the test, which can clearly influence the validity of its result. Other objections regarding the conclusions of both studies were that almost 25% of patients with a negative test in the first study, and 37% in the most recent study, had also shown clinical benefits from the treatment, and the test result was not able to differentiate between patients with symptom recurrence, so the practical utility of the test for therapeutic decision-making was questionable.

Meanwhile, a clinical trial conducted in war veterans with IBS without constipation could not demonstrate that pre-treatment values of the lactulose test correlated with symptom improvement after treatment with rifaximin.48 Other authors have even reported that the best response to antibiotics was seen precisely in the group of patients with less than 20 ppm H2 and CH4 elevation throughout the entire test.49 Lastly, another retrospective study carried out in an Asian population with IBS without constipation concluded that the pre-treatment values of the lactulose test were not able to predict the need to prolong treatment with rifaximin.50

Evaluating the same objective using other diagnostic techniques, results have been published from a study that performed duodenal aspirate culture on 1263 consecutive patients who underwent upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopy for different gastrointestinal functional disorders. The subsequent indication of whether or not to administer antibiotic therapy was at the discretion of the responsible physician, with rifaximin, ciprofloxacin or metronidazole being the most commonly used options. A retrospective analysis found that treatment was effective in improving symptoms, but the culture result did not predict therapeutic success.51

Regarding the use of probiotics (PB), there is no consensus regarding the potential role of performing a SIBO diagnostic test to predict the outcome of therapy. In a randomised clinical trial, early H2 peak in the lactulose test did not predict the effect of a fermented milk probiotic preparation (Lactobacillus casei, strain Shirota) in yielding normal test results in patients with IBS. The test positivity rate was no different at the end of the treatment period compared to that found with placebo (36% vs 41%; P = 1.00).52 It should be noted that the preparation used in this study did not improve gastrointestinal symptoms compared to placebo, so the results could differ when considering PB with different mechanisms of action. In fact, a post-hoc study of a subsequent trial with a product containing several strains of Bifidobacterium lactis, Lactobacillus spp and Streptococcus thermophilus, and applying a lactulose test with measurement of H2 and CH4, concluded that only in those patients with elevated H2 (not CH4) did the product improve symptoms, reduce intestinal gas production and yield normal test results.53

Data linking diet to breath test results are very limited. The only published data come from a retrospective study carried out in 2004 that included 93 patients with a positive lactulose test, who agreed to follow an elemental diet; 80% of them tested negative, and a significant reduction in symptoms was found in this group compared to those in whom the test remained positive.54 There is no similar information evaluating the effect with other diets and no other studies have reproduced these results. Furthermore, the elemental diet is only used marginally due to its lack of palatability and difficulty maintaining it in the long term. All of this affects the practical value of what this observation can offer.

In patients meeting IBS criteria in particular, it may be useful to determine whether breath tests used for SIBO diagnosis predict the effect of treatments aimed at modulating visceral hypersensitivity. In a prospective analysis, Onana et al.55 were unable to demonstrate that the production of H2 and CH4 during the glucose test was associated with greater severity of IBS symptoms (r = 0.84; P = .02 and r = 0.64; P = .05, respectively). Previously, Le Nevé et al.56 had evaluated the same aspect and found that, although the numerical value of the H2 exhaled during the test was not linked to symptom severity, those who experienced more intense symptoms after the administration of a nutritional preparation containing 25 g of lactulose more frequently also had markers of hypersensitivity, especially abdominal pain due to rectal barostat distension (P < .001). This could theoretically facilitate the selection of patients who are candidates for new therapies, although to date this finding has not been translated into practice.

Response. The results of breath tests and cultures have not been shown to be a useful tool to guide the indication of antibiotic therapy, nor to support a change in drug regimen duration. The utility of predicting the effect of a probiotic is probably determined by its effectiveness and mechanism of action, so a generic recommendation cannot be issued. Moreover, the role of the test in selecting patients who are candidates for new therapies or specific diets has not yet been fully defined, although the available evidence does not afford it a position of clinical relevance as a predictor of effectiveness.

How useful are dietary measures?Evidence on the management of SIBO with dietary measures is limited and of low quality. There is only one published study on this subject, which has already been cited to argue the response in the previous section. Pimentel et al.54 retrospectively described a 14-day elemental diet intervention (complete nutrition free of amino acids, not allowing other foods, soft drinks, chewing gum or caffeine) in a cohort of patients diagnosed with IBS using Rome I criteria and with a positive lactulose breath test. After two weeks, the lactulose test was normal in 80% of patients, and of the non-responders, 5% achieved the same target after extending the diet for seven more days. Only 57% of the cohort showed symptom improvement, although the rate was significantly higher among those whose test results had returned to normal (66.4% vs 11.9%). As already mentioned, the poor palatability of the elemental diet is clearly a limiting factor for its proposal as a medium and long-term therapeutic solution.

Mindful eating, which involves eating in orderly patterns of fasting and eating, choosing and cooking the right foods on a daily basis, could have an effect on the cycles of the migrating motor complex (MMC). Patients diagnosed with SIBO appear to have a lower frequency of MMC phase III, so mindful eating has a potential role in SIBO.57

Fibre intake appears to affect the microbiota of the small intestine. A culture consistent with SIBO has been described in up to 50% of individuals with high fibre intake. However, all of them were asymptomatic. Reducing dietary fibre has effects on both abdominal symptoms in IBS patients and breath tests, but different studies have yielded conflicting results.9

Other approaches, such as a diet low in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAP), fructo-oligosaccharide treatment or faecal transplantation have demonstrated efficacy in modifying the intestinal microbiota, although none of them include cohorts of patients with SIBO, but rather people with IBS.58 A low FODMAP diet is effective in IBS. In its restriction phase, it decreases Bifidobacteria (gas producers, although it is a protective factor against carcinogenesis) without reducing the overall diversity of the intestinal microbiome, metabolites or faecal pH. This effect appears to disappear in the food reintroduction phase.59 Furthermore, certain microbiota subtypes have been described that predict response to a low FODMAP diet.60

Restrictive diets are usually low in residue and improve gas-related symptoms, which is attributed to less fermentation. If this modification is maintained over time, the changes it causes in the microbiome and its metabolic pathways could also lead to long-term harm. It has not been precisely established how long the above changes persist and their effects after the diet is stopped.

In light of the above, some dietary interventions are potentially useful therapeutic resources for SIBO, but their indication is conditional on having specific, well-directed studies that yield favourable results. The design of these studies should also include a sufficiently long follow-up period to determine whether adaptive changes in the microbiota and its metabolic pathways are maintained over time, and whether this phenomenon leads to other complications.

Response. Although dietary measures have the potential to modify the intestinal microbiota and its metabolism, there is a marked lack of evidence concerning any potential benefit in SIBO, and the harm it may entail. Furthermore, the published studies include patients diagnosed exclusively by breath testing. There is therefore a lack of scientific basis to draft dietary recommendations with the aim of specifically treating SIBO. Moreover, the indication of restrictive diets carries a high risk in the management of patients with functional gastrointestinal disease, in whom an eating disorder frequently underlies the condition.

How effective are antibiotics?According to the North American Consensus, oral antibiotics play a central role in the treatment of SIBO,23 although there are no universally accepted therapeutic approaches. Different broad-spectrum antibiotics, such as rifaximin, norfloxacin, ciprofloxacin, tetracyclines, doxycycline, neomycin, co-trimoxazole, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and metronidazole, have been described as possible treatments for SIBO (see results of the meta-analyses available in Table 2).

Efficacy of antibiotics in the treatment of SIBO. Summary of available meta-analyses.

| Author | Type of study | Number of studies included | Antibiotic (number of patients) | Population | Diagnostic method | Breath test normalisation rate (95% CI) | Symptomatic improvement rate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shah et al., 201361 | Meta-analysis (RCT) | 10 | Rifaximin (365) | CrD (2) | LT (3) | Rifaximin: 49.5% (44.0–55.1) | Rifaximin: 87%–91% |

| Metronidazole (86) | IBS (1) | LT + GT (1) | Metronidazole: 51.2% (40.1–62.1) | Neomycin: 34.4%–61.7% | |||

| Neomycin (41) | CD (1) | GT (6) | Neomycin: 19.5% (8.8–34.9) | Others found no differences (2) or they were not reported (4) | |||

| Ciprofloxacin (14) | CAP (1) | Ciprofloxacin: 100% (76.8–100) | |||||

| Chlortetracycline (11) | GI (5)* | Chlortetracycline: 27.3% (6.0–61.0) | |||||

| Total: 51.1% (46.7–55.5) | |||||||

| Gatta et al., 201763 | Meta-analysis (8 RCT and 24 OS) | 32 | Rifaximin | Hypothyroidism (27) | LT (17) | ITT: 70.8% (61.4–78.2), I2 = 89.4% | 67.7% (44.7–86.9), I2 = 91.3% |

| 600–1600 mg/day (5–28 days) | GI (1139)* | GT (13) | PP: 72.9% (65.5–79.8), I2 = 87.5% | ||||

| ITT (1331) | Acromegaly (18) | LT + GT (2) | |||||

| PP (1274) | Scleroderma (30) | ||||||

| Rosacea (68) | |||||||

| Parkinson's (18) | |||||||

| Diabetes I and II (21) | |||||||

| Shah et al., 202025 | Meta-analysis | 25 | Rifaximin (212) | IBS (3192) | LT (8) | GT: 147/158 (93.0%) | 81.6% (76.7–86.5) |

| Case-control | Ciprofloxacin (7) | Antibiotic analysis subgroup (239) | GT (9) | Culture: 5/7 (71.4%) | |||

| Norfloxacin (8) | XT (2) | Rifaximin vs fluoroquinolones (83% vs 66%) | |||||

| Not specified (12) | ST (1) | ||||||

| Culture (5) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 202164 | Meta-analysis (5 RCT and 21 OS) | 26 | Rifaximin (874) | Liver cirrhosis (115) | LT (10) | Rifaximin: | Significant improvement (15) |

| GI (440)* | GT (14) | ITT: 59% (50–69), I2 = 90.7% | No improvement (3) | ||||

| Urticaria (13) | BT (2) | PP: 63% (53–72), I2 = 90.3% | |||||

| Parkinson's (47) | Eradication rate: 80% at a dose of 1600 mg/day for one week | ||||||

| Cystic fibrosis (79) | |||||||

| Rosacea (90) | |||||||

| Hypothyroidism (50) | |||||||

| Systemic sclerosis (40) | |||||||

| Shah et al., 202371 | Meta-analysis | Subgroup analysis (9/28) studies | Rifaximin (54) | Scleroderma (1112) | LT (3) | Metronidazole: 38% | 60.4% (95% CI: 49.9–70.2) |

| Prevalence (11) or case-control (11) | Metronidazole (26) | SIBO prevalence: 39.9% (95% CI: 33.1–47.1; P = .006, I2 76%) | GT (4) | Rifaximin: 77% | |||

| Ciprofloxacin (8) | Subgroup (158) | Culture (2) | Ciprofloxacin and chloramphenicol: NR | ||||

| Rotating antibiotics (58) | Rotating ATB: 44.8% | ||||||

| Chloramphenicol (12) | Rifaximin vs rotating ATB: 77.8% (95% CI, 64.4–87.9) vs 44.8% (95% CI: 31.7–58.4) | ||||||

| Total: 56% (47.8−64.9) |

RCT: randomised controlled clinical trial; OS: observational studies; IBS: irritable bowel syndrome; CAP: chronic abdominal pain; CrD: Crohn's disease; CD: coeliac disease; ITT: intention-to-treat analysis; PP: per-protocol analysis; LT: lactulose breath test; GT: glucose breath test; ST: sucrose breath test; XT: xylose breath test; BT: unspecified breath test; NR: not reported; ATB: antibiotic.

According to the results of one meta-analysis,61 antibiotics were more effective than placebo, with a breath test normalisation rate (glucose or lactulose) of 51.1% (95% CI: 46.7%–55,5%) for antibiotics compared to 9.8% (95% CI: 4.6%–17.8%) obtained with placebo, with an OR of 2.6% (95% CI: 1.3%–5.0%). For symptom relief, a response rate of 49.5% has been reported in patients treated with antibiotics (rifaximin, norfloxacin or neomycin) versus 13.7% in those who did not receive antibiotics.62

The most frequently used antibiotic is rifaximin, whose systemic absorption is lower than 0.4%, reaching high concentrations in the intestinal lumen. A systematic review and meta-analysis63 included 32 studies with 1331 patients with SIBO treated with rifaximin. The dose varied from 600 mg to 1600 mg daily, with courses ranging from five to 28 days. The authors showed that the overall eradication rate (negative glucose or lactulose breath test) was 70.8% (95% CI: 61.4%–78.2%; I2 = 89.4%) according to the intention-to-treat analysis, and 72.9% (95% CI: 65.5%–79.8%; I2 = 87.5%) according to the per protocol analysis. A subgroup analysis of IBS patients was performed in 10 studies. The intention-to-treat analysis showed an eradication rate of 71.6% (95% CI: 56.7%–84.4%; I2 = 86.4%) and the per protocol analysis, 75.4% (95% CI: 65%–84.5%; I2 = 81.7%). In another case-control meta-analysis,25 the efficacy of different antibiotics was evaluated in 239 patients with SIBO: rifaximin (four studies); ciprofloxacin (one study); norfloxacin (one study); and another where the type of antibiotic was not specified. Symptom improvement was reported in 81.6% (95% CI: 76.7%–86.5%). Overall, the efficacy of rifaximin was better than that of fluoroquinolones (83% vs 66%), particularly in patients with diarrhoea-predominant IBS. More recently, another systematic review and meta-analysis64 analysed a total of 21 observational studies and five randomised clinical trials (n = 874). The overall eradication rate for rifaximin was 59% (95% CI: 50%–69%; I2 = 90.7%) according to the intention-to-treat analysis, and 63% (95% CI: 53%–72%; I2 = 90.3%) according to the per protocol analysis. However, in all of these studies, the investigators observed significant heterogeneity.

Although rifaximin has been the most studied antibiotic, other antibiotics with systemic action have been described. However, the level of evidence to recommend their systematic use is low.65–69 In a cohort of 145 patients with Crohn's disease,67 who were given a lactulose breath test, the test was positive in 30 cases (20%) and confirmed with glucose test in 29/30 patients. The prevalence of SIBO was higher in patients with previous surgery compared to those without surgery (33% vs 14%: P = .007) and in those with at least one stricture compared to those without (29% vs 14%: P = .03). The 29 patients diagnosed with SIBO were randomised into two groups: group A (15 patients) received metronidazole (250 mg/8 h); and group B (14 patients) received ciprofloxacin (500 mg/12 h), both for 10 days. No significant differences were found in the normalisation of the breath test between the group treated with metronidazole and the group treated with ciprofloxacin (13/15 and 14/14, respectively). In another cohort of 142 patients with SIBO (diagnosed by glucose breath test), patients were randomly assigned to two seven-day treatment groups: rifaximin 1200 mg/day; and metronidazole 750 mg/day.69 The breath test normalisation rate was significantly higher in the rifaximin group compared to the metronidazole group (63.4% vs 43,7%; P < .05; OR 1.50; 95% CI: 1.1–4.4).

Information is also available from a retrospective study70 on patients diagnosed with SIBO which, with a glucose test, evaluated the effect of using a fixed antibiotic (quinolone or nitroimidazole) for periods of 10 days per month for three consecutive months, versus rotating the same antibiotics one after the other for the same period of time. The result was a higher percentage of remission in the rotating antibiotic group (70% vs 51%; P = .05), but without significant differences in the frequency of recurrence (10% vs 5%; P = .147) or in time to recurrence (14 vs 36 months; P = .453).

In a meta-analysis71 of 28 studies including 1112 patients with scleroderma, the pooled prevalence of SIBO was 39.9% (95% CI: 33.1–47.1). Nine studies with 158 patients reported response to antibiotic therapy; 60.4% (95% CI: 49.9–70.2) of these patients reported significant improvement in symptoms; in 56% (95% CI: 47.8–64.9) of patients the breath test normalised after treatment with antibiotics. In one study, a patient treated with rotating antibiotics developed pseudomembranous colitis, leading to discontinuation of the antibiotic.72 Rifaximin was significantly more effective than rotating antibiotics in eradicating SIBO in patients with scleroderma (77.8% [95% CI: 64.4–87.9]) vs 44.8% [95% CI: 31.7–58.4]; P < .05).

Another subgroup of patients in which combined antibiotic treatments were tested comprised patients with a positive CH4 breath test (Table 3). This is more prevalent in patients with a predominance of constipation.25,75 The main microorganism responsible for the formation of CH4 in the intestine is the archaea M. smithii. In a prospective, double-blind, randomised study of 31 patients,76 16 treated with neomycin and placebo and 15 with neomycin and rifaximin, after treatment the severity of constipation was found to be significantly lower in the neomycin and rifaximin group (28.6 ± 30.8) than with neomycin alone (61.2 ± 24.1) (P = .0042). In the neomycin and rifaximin group, subjects with CH4 < 3 ppm after treatment reported significantly lower constipation severity (30.5 ± 21.8) than those with persistent CH4 (67.2 ± 32.1) (P = .020). In another retrospective study,77 patients with a positive CH4 lactulose test received one of three antibiotic treatments: 1000 mg/day of neomycin alone for 10 days (n = 8), 400 mg/day of rifaximin alone for 10 days (n = 39) or a combination of rifaximin and neomycin for 10 days (n = 27). In the patients who took the combination treatment, 85% had a clinical response, compared to 63% in the neomycin alone group (P = .15) and 56% in the rifaximin alone group (P = .01). In 87% of the subjects treated with rifaximin plus neomycin, CH4 was eradicated in their breath test, compared to 33% of subjects in the neomycin group (P = .001) and 28% in the rifaximin group (P = .001). Out of the patients who did not eliminate CH4 and had received rifaximin alone, 66% of those who subsequently used treatment with rifaximin plus neomycin achieved normal breath tests. However, solid conclusions cannot be drawn owing to the small sample size of both studies.

Antibiotics with demonstrated activity against archaea in humans.73,74

| Antibiotic | Mechanism of action | Effectiveness in human methanogenic archaea |

|---|---|---|

| Imidazoles (metronidazole) | Interfere with DNA replication/transcription | YES |

| Quinolones | Interfere with DNA replication/transcription | NO |

| Nitrofurans (nitrofurantoin, furazolidone) | Interfere with DNA replication/transcription | NO |

| Sulphonamides and diaminopyridines | Interfere with DNA replication/transcription | NO |

| Aminocoumarin (novobiocin) | Interferes with DNA replication/transcription | Probably YES |

| Squalamine | Alters the cell wall | YES |

| Bacitracin | Alters the cell wall | NO |

| Aminoglycosides | Inhibit protein synthesis | NO |

| Fusidic acid | Inhibits protein synthesis | Probably YES |

| Rifaximin | Inhibits RNA synthesis | YES |

In view of the above, the level of evidence supporting the use of systemic antibiotic therapy must be classified as poor. Furthermore, it must be remembered that the recurrence rate of SIBO is high, especially in patients with anatomical alterations or serious systemic diseases, and in this scenario there is even less evidence available. A recurrence of SIBO symptoms has been reported in 12.6%, 27.5% and 43.7% of patients at three, six and nine months after successful treatment (normal glucose test), respectively.78 The need to repeat antibiotic therapy can generate resistant bacteria, adverse reactions and an increase in opportunistic infections such as Clostridioides difficile. Some authors recommend using rifaximin, given its good tolerance, good safety profile, its ability to generate “eubiotic” effects and its low risk of resistance.7,79,80

Response. Antibiotic efficacy varies depending on the type of antibiotic and the dose. There is no universally accepted therapeutic approach for either initial treatment or recurrence of SIBO. The lack of large randomised clinical trials evaluating the effects of antibiotics in the treatment of SIBO limits the ability to draw firm conclusions about efficacy. However, rifaximin is the most widely evaluated antibiotic. In the most recent studies, the cure rate fluctuates between 59% and 63%, depending on the dose and duration of treatment, but it must be taken into account that the recurrence rate is high (43.7% after nine months). The use of other antibiotics should be limited due to the risk of resistance, adverse reactions and increased opportunistic infections, although some selected cases with predisposing disorders involved in severe SIBO may be an exception to the rule. In these situations, it seems reasonable to be less restrictive in the prescribing of antibiotics, even applying cyclical regimens when recurrence is frequent. Data on specific treatment of IMO are very limited, and although it has been suggested that the combination of rifaximin plus neomycin could be superior to monotherapy, confirmatory data is lacking.

Are probiotics beneficial?Some PB have been shown to improve lower abdominal symptoms, mainly in the context of IBS or antibiotic use, as well as modify the composition of the microbiome and alter its metabolic pathways.81 The clinical benefit described may be due not only to its direct eubiotic action, but also possibly supported by the reduction in inflammatory mediators and tissue damage, which is attributed to the dysbiosis.82 The results of a systematic review of clinical trials concluded that certain strains, at specific doses, could relieve symptoms such as pain, abdominal bloating, constipation and, although less likely, also meteorism. To control diarrhoea, however, scientific evidence did not seem to support the indication of this treatment in patients with IBS, but it did support it in patients undergoing eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori.83 It was concluded that the large number of strains analysed, the combination of these in different preparations, as well as the different doses used, prevented specific recommendations from being made for each clinical scenario.

A subsequent non-randomised study including 33 patients found significantly greater overall symptom improvement in those with IBS and a diagnosis of SIBO who took a multi-strain preparation composed of Saccharomyces boulardii, B. lactis BB-12, Lactobacillus acidophilus LA-5 and Lactobacillus plantarum, compared to those with negative SIBO (71.6% improvement on the symptom rating scale used versus 10.6% achieved in the patients without SIBO; P = .017). However, some common IBS symptoms improved independent of the presence of this factor.84 A randomised clinical trial, also with a small sample size (25 cases and 25 controls) with patients with various functional gastrointestinal symptoms found that supplementation with Bacillus subtilis and Enterococcus faecium accompanied by a colonoscopy with intestinal preparation with polyethylene glycol was linked to symptom improvement and a reduction in the positivity rate of lactulose breath tests for SIBO, going from 60% for cases and 52% for controls before treatment (P = .254), to 28% and 56%, respectively, after treatment (P < .001).85 Another clinical trial that administered Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 along with a diet low in fermentable foods to patients with IBS and SIBO reduced symptoms and H2 production compared to prescribing diet alone (P = .044), but not significantly for those diagnosed with SIBO (59.3% in the group with PB + diet and 71.4% in the diet-only group; P = .38).86

A meta-analysis that included 22 studies with any type of PB and diagnoses with H2 testing with glucose or lactulose substrate87 was not able to demonstrate that the use of PB prevents the development of SIBO (relative risk [RR] = 0.54; 95% CI: 0.19–1.52; P = .24), but it was associated with improvement in symptoms (RR = 1.61; 95% CI: 1.19–2.17; P < .05). Three of the studies included had compared the use of PB and antibiotics for the treatment of SIBO. One of them was a retrospective study, which found no significant difference in symptom resolution between the two groups (38% in the antibiotic group vs 18% in the PB group; P = .091). However, in the subanalysis of two clinical trials that compared PB and metronidazole, a significant difference was found in the resolution of SIBO in favour of PB (RR = 1.49; 95% CI: 1.07–2.08; P < .05), but the result was only verified by H2 testing in one of them.

Data in patient groups with specific conditions or disorders other than IBS who are at increased risk for SIBO are conflicting. In one placebo-controlled study with patients who had undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, assessed by H2 testing with glucose substrate, the administration of L. acidophilus and B. lactis was associated with improvement in bloating (P = .022), but not with a reduction in the development of SIBO 12 weeks after surgery (12.1% vs 14.8%, respectively; P = .938).88 In patients with chronic liver disease, a combination of six PB (Bifidobacterium bifidum, B. lactis, Bifidobacterium longum, L. acidophilus, Lactobacillus rhamnosus and S. thermophilus) resulted in a reduction in SIBO cases compared to placebo (24% vs 0%; P < .05)89; and in a trial that included patients with cirrhosis, after treatment with S. boulardii for three months, the lactulose test was negative in 80% of patients, compared to 23.1% with placebo (P = .002), in conjunction with a reduction in the frequency of liver complications.90

However, a study in pregnant women with hypothyroidism that used lactulose substrate found a SIBO rate of 48.5% (24.8% in a control group of pregnant women without hypothyroidism), and the administration of a prebiotic combined with Bifidobacterium infantis, L. acidophilus, Enterococcus faecalis and Bacillus cereus was associated with a significant reduction in positive cases due to elevated CH4 (38.4%–3.8%; P < .001), which could not be corroborated for the positive cases due to elevated H2 (50.9%–38.4%; P = .06).91 In patients with systemic sclerosis, a randomised trial comparing S. boulardii with metronidazole and with the combination of the two found a 55% reduction in diagnoses in the combined group, compared to 33% with PB alone and 25% with the antibiotic alone (P < .01 in all cases), with worse symptom control also observed in the latter group.92

Another issue to keep in mind is that, although PB are very safe preparations, they are not, as is commonly thought, completely harmless. There is some evidence that in some cases they may even aggravate the symptoms of the disorder they are seeking to alleviate. Beyond descriptions of potential adverse effects in isolated cases, a clinical study in healthy volunteers, with administration of B. infantis 35624, commonly used in patients with IBS, showed no reduction in the production of H2, but was associated with a significant increase in the emission of CH4 during the test with lactulose (P = .012), without demonstrating clinical repercussions due to the phenomenon in the group studied.93 Another adverse effect that has been attributed to the use of PB is mental confusion (or foggy feeling in head), which appears to be mediated by the appearance of D-lactic acidosis, as a result of carbohydrate fermentation. It has been suggested that prolonged PB use may contribute to this phenomenon and that it might be resolved by discontinuing the PB and with the use of antibiotics.94

Response. PB appear to improve the symptoms most commonly attributed to SIBO and alter the composition and functioning of the intestinal microbiome. The benefit of these changes and their safety for indiscriminate use of the product have not been sufficiently established and not all trials with PB have found a reduced rate of SIBO diagnoses. There is also insufficient data to establish a specific recommendation regarding strain, duration of treatment and dosage adjusted to each clinical scenario. The large range of PB preparations available on the market, as well as the variability of combinations between countries, is another confounding factor for drawing practical post-marketing conclusions.

Are herbal remedies a viable alternative?Some studies have investigated alternative herbal medicine treatments. In a small cohort of 10 patients, four of them with SIBO, treatment with Daikenchuto (Japanese herbal preparation) failed to produce a negative glucose breath test, although it improved symptoms in the overall sample of patients.95 Another open-label study, with other herbal products (Dysbiocide combined with FC Cidal or Candibactin AR combined with Candibactin BR), included 104 SIBO patients (H2 and CH4). They were assigned, according to their preference, to 1200 mg daily of rifaximin or herbal treatment for four weeks. Negative lactulose test results were seen in 46% of the herbal therapy group and 34% of the rifaximin group. In the group of non-responders to rifaximin, 57.1% achieved a normal lactulose test after rescue with herbal treatment. Another group of non-responders to rifaximin received rescue therapy with clindamycin 300 mg, metronidazole 250 mg and neomycin 500 mg three times a day, with 60% achieving negative tests, with no differences compared to response to herbal treatment. However, this study does not mention the effect of the treatments on the participants' gastrointestinal symptoms.96

Response. Herbal remedies, although offering initial results that are certainly promising, lack sufficient scientific support for their systematic recommendation.

Conclusions- 1

To date, there is no precise and universally accepted definition of SIBO that would allow criteria to be established for a diagnosis that would either confirm or rule out SIBO.

- 2

SIBO is linked to predisposing factors, most frequently related to severe abnormalities in intestinal motility or anatomical changes in the gastrointestinal tract. Its diagnosis in clinical contexts without recognised predisposing factors should be questioned.

- 3

SIBO's spectrum of symptoms is very varied, ranging from mild symptoms or subclinical lab test abnormalities to a malabsorption syndrome and/or severe symptoms. The symptoms are poor predictors of SIBO. Diarrhoea is the most consistently associated symptom. Bloating and abdominal distension do not predict SIBO, so it does not seem justified to start diagnostic testing for the condition based solely on the manifestation of these symptoms.

- 4

There is no gold standard for diagnosing SIBO. There is no unanimous agreement that determines unequivocally and under any circumstances the number of microorganisms that should be considered pathological in an intestinal aspirate culture. This test is also invasive and technically complex to implement regularly in clinical practice.

- 5

Breath tests are non-invasive and inexpensive diagnostic alternatives that have low accuracy, so their results alone are not sufficient to establish a diagnosis or justify initiating treatment. They have not been shown to be useful tools for predicting response to treatment or for guiding the indication for treatment (for example, type of antibiotic, duration of treatment, appropriate diet). Their results must be interpreted by a doctor, taking into account the pre-test probability of each specific case.

- 6

Although restrictive diets can modify the intestinal microbiome and its metabolic pathways, there is insufficient information available to include them among the options for the treatment of SIBO. Their potential harmful effects on patients must also be considered.

- 7

The antibiotic most widely studied and with the highest level of scientific evidence to support its use as a treatment for SIBO is rifaximin. Except in specific clinical situations of manifest refractoriness and predisposing factors that lead to severe SIBO, the use of other antibiotics does not seem justified. Despite this, it should be considered that the effectiveness of rifaximin is 60%, and that SIBO recurrence is around 50% at 12 months. The use of cyclical regimens seems reasonable when recurrent SIBO is detected. In cases with a diagnosis of IMO, the combination of rifaximin and neomycin could yield better results than these antibiotics in monotherapy.

- 8

Some PB have been shown to improve symptoms commonly associated with SIBO, and can also modify the microbiome, so they have a potential role in treatment. However, it is not yet possible to make a specific recommendation for the use of PB, as neither the strain or strains that provide the greatest benefit, nor their optimal dose and duration of treatment, have been determined.

- 9

The therapeutic efficacy of herbal remedies in patients with SIBO remains uncertain.

- 10

There is a need to develop safe and more accurate diagnostic tests for SIBO, as well as more effective therapeutic strategies. Until both are available, the widespread use of available diagnostic tools without a well-established indication - i.e., where well-defined predisposing factors are lacking - should be avoided. Similarly, expectations placed on the eradication of SIBO as a universal solution for the relief of common gastrointestinal symptoms, such as abdominal bloating, should be limited, as more often than not this course will not achieve significant clinical improvement.

Results of the expert group vote. Survey completed by the authors of the document on 25 statements, with a five-point Likert scale denoting the degree of agreement with the statements. The statements with over 80% total agreement and agreement with reservations and those with less than 10% total or partial disagreement were accepted. In the remaining cases it was considered that there was not sufficient agreement to accept the statement as consensual (Table 4).

Statements and degree of consensus of the group of experts.

| STATEMENTS | Consensus |

|---|---|

| 1. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth is defined by an increase in the bacterial load that colonises this section of the gastrointestinal tract capable of causing symptoms and well-defined lab test abnormalities. | Accepted |

| 2. The diagnostic cut-off point is 103 CFU per millilitre of duodenal or jejunal aspirate, cultured on MacConkey agar. | Accepted |

| 3. Certain taxonomic changes, with a predominance of coliforms, are required in order to diagnose SIBO. | No consensus |

| 4. The development of SIBO is associated with certain predisposing factors. | Accepted |

| 5. The clinical spectrum of SIBO is very broad, ranging from paucisymptomatic forms to severe malabsorption. | Accepted |

| 6. The symptom that has shown the highest degree of association with SIBO is diarrhoea. | Accepted |

| 7. Abdominal bloating or distension is not associated with an increased risk of presenting with SIBO in patients without predisposing factors. | Accepted |

| 8. In the absence of one or more of the defined predisposing factors, diagnostic testing for SIBO is NOT indicated. | Accepted |

| 9. Symptoms cannot predict the positivity of diagnostic tests. | Accepted |

| 10. Diagnostic tests do not predict symptomatic response to a restrictive diet. | Accepted |

| 11. Diagnostic tests do not predict symptomatic response to antibiotic therapy in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. | Accepted |

| 12. The H2 and CH4 tests with glucose substrate are superior overall in sensitivity and specificity to the tests with lactulose. | Accepted |

| 13. In patients with a history of gastrointestinal resection, a positive glucose test result should more likely be attributed to accelerated intestinal transit and considered a false positive for SIBO. | Accepted |

| 14. To improve the interpretation of the results of an H2/CH4 test for the diagnosis of SIBO, it is advisable to also perform an intestinal transit evaluation test. | No consensus |

| 15. Intestinal aspirate culture is considered to be the diagnostic test of choice, but it CANNOT be considered a gold standard. | Accepted |

| 16. The technical complexity of performing the culture limits its use in clinical practice. | Accepted |

| 17. The diagnostic value of PCR tests on intestinal biopsy, stool or intestinal aspirate have NOT been shown to be superior to culture. | Accepted |

| 18. The trial of restrictive diets for the treatment of SIBO has NO scientific support for being included among the measures with therapeutic effect. | Accepted |

| 19. The effect of a long-term restrictive diet on the composition and metabolic pathways of the microbiome is still uncertain. Its potential long-term complications are an additional reason to advise against its use in SIBO. | Accepted |

| 20. Rifaximin is the treatment of choice for the treatment of SIBO. | Accepted |

| 21. No differences in effectiveness have been demonstrated between the different systemic antibiotics tested. | No consensus |

| 22. The indication of rotating antibiotics is acceptable in patients with a predisposing factor associated with recurrent SIBO. | Accepted |

| 23. Recurrence of SIBO is very common and should be treated with rifaximin. | No consensus |

| 24. The use of probiotics to treat SIBO or its symptoms cannot be recommended generically. | Accepted |

| 25. There is insufficient evidence to support the use of herbal remedies among therapeutic measures for SIBO. | Accepted |

This document has been endorsed by the Asociación Española de Gastroenterología [Spanish Association of Gastroenterology] and the Asociación Española de Neurogastroenterología y Motilidad [Spanish Association of Neurogastroenterology and Motility], both of which have covered the publication costs, without receiving external funding.

Document reviewing scientific evidence and Consensus of the Group of Experts of the Asociación Española de Gastroenterología (AEG) [Spanish Association of Gastroenterology] and the Asociación Española de Neurogastroenterología y Motilidad (ASENEM) [Spanish Association of Neurogastroenterology and Motility].