Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a chronic liver disease that affects adipose function. This study aimed to explore the function of adipocytes-derived exosomal (ADEs) miR-122 in NAFLD.

MethodsA high-fat and high-fructose diet-induced rat model and a palmitic acid (PA)-induced in vitro model were established. The RNA level of miR-122 and Sirt1 was measured using qRT-PCR. The protein levels of exosome biomarkers, and lipogenesis, inflammation and fibrosis biomarkers were determined by western blotting. Cell viability and apoptosis were assessed using cell counting kit-8 and flow cytometry, respectively. Serum alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, total cholesterol, triglyceride levels were measured. Liver tissue damage was assessed using haematoxylin and eosin staining. The interaction between miR-122 and Sirt1 3′UTR was assessed using a luciferase reporter gene assay.

ResultsADEs exhibited abundant level of miR-122 and promoted lipogenesis, impaired hepatocyte survival, enhanced liver damage and increased serum lipid levels in vivo and in vitro. Inhibition of miR-122 in ADEs alleviated NAFLD progression, lipid and glucose metabolism, liver inflammation and fibrosis both in vivo and in vitro. miR-122 binds directly to the 3′UTR of Sirt1 to suppress its expression. Moreover, Sirt1 overexpression reversed the increase in cell apoptosis, glucose and lipid metabolism, liver inflammation and fibrosis induced by ADEs in vivo and in vitro.

ConclusionsThe ADEs miR-122 promotes the progression of NAFLD via modulating Sirt1 signalling in vivo and in vitro. The ADEs miR-122 may be a promising diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target for NAFLD.

La enfermedad del hígado graso no alcohólico (EHGNA) es una enfermedad hepática crónica que afecta a la función adiposa. Este estudio tiene como objetivo explorar la función de los exosomas derivados de los adipocitos (ADEs) miR-122 en la EHGNA.

MétodosSe estableció un modelo de rata inducido por una dieta alta en grasas y fructosa y un modelo in vitro inducido por ácido palmítico (AP). Se midió el nivel de ARN de miR-122 y Sirt1 mediante qRT-PCR. Los niveles de proteína de los biomarcadores de exosomas y los biomarcadores de lipogénesis, inflamación y fibrosis se determinaron mediante western blotting. La viabilidad celular y la apoptosis se evaluaron mediante el kit de recuento de células-8 y la citometría de flujo, respectivamente. Se midieron los niveles séricos de alanina aminotransferasa, aspartato aminotransferasa, colesterol total y triglicéridos. El daño tisular del hígado se evaluó mediante tinción con hematoxilina y eosina. La interacción entre miR-122 y Sirt1 3’UTR se evaluó mediante un ensayo de gen reportero de luciferasa.

ResultadosLos ADEs mostraron un nivel abundante de miR-122 y promovieron la lipogénesis, perjudicaron la supervivencia de los hepatocitos, potenciaron el daño hepático y aumentaron los niveles de lípidos séricos in vivo e in vitro. La inhibición de miR-122 en los ADEs alivió la progresión de la EHGNA, el metabolismo de los lípidos y la glucosa, la inflamación del hígado y la fibrosis tanto in vivo como in vitro. miR-122 se une directamente a la 3’UTR de Sirt1 para suprimir su expresión. Además, la sobreexpresión de Sirt1 revirtió el aumento de la apoptosis celular, el metabolismo de la glucosa y los lípidos, la inflamación del hígado y la fibrosis inducida por los ADEs in vivo e in vitro.

ConclusionesEl ADEs miR-122 promueve la progresión de la EHGNA a través de la modulación de la señalización de Sirt1 in vivo e in vitro. El ADEs miR-122 puede ser un prometedor biomarcador de diagnóstico y diana terapéutica para la EHGNA.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a major type of chronic liver disease that occurs in more than 25% of the general population every year, with increasing incidence.1 NAFLD is commonly caused by fat deposition in the liver due to pathological factors other than alcohol and could progress to liver cirrhosis and even liver cancer.2 An increasing number of studies have disclosed the risk factors that correlate with NAFLD, including dyslipidaemia, hypertension, serum triglyceride (TG) levels, obesity, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes mellitus.3,4 Studies have revealed several possible mechanisms underlying NAFLD, such as insulin resistance, nutritional factors, adipose tissue-secreted hormones, genetic and epigenetic factors, and gut microbiota.5,6 However, the exact mechanisms have not been elucidated, and no efficient therapeutical treatment is currently available.

NAFLD has been reported to correlate with elevated visceral adipose tissue and metabolic dysregulation.7,8 The adipose tissues were initially recognised as nutrients and energy storing tissues.9 However, recent studies have revealed the role of adipose tissue as secretory tissues.10,11 Adipose tissues release various adipokines (including visfatin, leptin, adipsin, adiponectin, and resistin) to modulate the function of other organs.12,13 Moreover, adipose tissues can secrete extracellular vesicles (EVs).14 Adipose-derived EVs can regulate specific targets due to their bio-active cargos, which are diverse from soluble adipokines. Exosomes are an important form of EVs that consist of subcellular membrane structures and contain various regulatory factors such as proteins, lipids, RNAs, and DNAs.15

microRNAs (miRNAs) are the primary components delivered by exosomes.16 miRNAs are noncoding RNAs with short sequences that can interact with targeted mRNAs to induce mRNA degradation or impede gene transcription.17 Recent studies have revealed the roles of miRNAs in NAFLD.18 For example, analysis on serum noncoding RNAs revealed that several miRNAs (miR-375, miR-122, and miR-192) are correlated with NAFLD severity.19 A recent study has suggested that miR-122 promotes lipogenesis in the liver by targeting Sirt1.20

In this study, we established a high-fat and high-fructose (HFHF) diet-induced in vivo rat NAFLD model and a palmitic acid (PA)-induced in vitro model to determine the function of adipocytes-derived exosomal (ADEs) miR-122 in progression of NAFLD. We measured viability, apoptosis, glucose and lipid metabolism in hepatocytes treated with ADEs miR-122 and simultaneously evaluated the secretion of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total cholesterol (TC), and triglyceride (TG). Our data suggest that ADEs miR-122 may be a diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target for NAFLD.

Materials and methodsMaterialsPalmitic acid (PA) and MTT reagent were purchased from Sigma (USA). Sirt1 overexpressing vector pcDNA-Sirt1 and empty vector pcDNA-3.1, miR-122 mimics, miR-122 inhibitor, and negative control (NC) mimics were obtained from Fulengen (Guangzhou, China). AVV9-Sirt1 and AVV9-NC were obtained from GeneChem (Shanghai, China). Lipofectamine 2000 reagent was purchased from Invitrogen (USA). Luciferase reporter gene vectors containing wild-type (WT) or mutant (MUT) Sirt1 3′UTR were synthesised by GenePharma (Shanghai, China). TheAnnexin V/PI Apoptosis Detection Kit was purchased from Beyotime (Shanghai, China). Primary antibodies against CD81, CD63, Alix, G6Pc, PEPCK, FAS, SREBP-1c, PPARα, Sirt1, TNF-α, IL-1β, Collagen I, α-SMA, and β-actin were purchased from Abcam (USA).

Exosome isolation and characterisationBlood samples were collected from patients with NAFLD and centrifuged to collect plasma. Exosomes in the supernatant of 3T3-L1 cells and plasma were extracted using a commercial Exosome Extraction Kit (KeyGEN BioTECH, Jiangsu, China) according to the manufacturer's protocol.21 Briefly, the samples were centrifuged at 4°C and 3000×g for 10min. The supernatant was then filtered through a 0.22μm filter, reacted with reagent A at 4°C for 60min, followed by reaction with reagent A at 4°C for 60min. The samples were then centrifuged at 4°C and 12,000×g for 20min, resuspended in PBS (100μl) and stored at −80°C for later use. The concentration of ADEs was measured using the bicinchoninic acid method (Beyotime, China). The morphology of the extracted ADEs was examined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM; JEOL, Japan). Particle size was measured by using a Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) system (Malvern, UK).

Cell culture and treatmentLO2 and 3T3-L1 cells were obtained from the Shanghai Cell Bank of Chinese Science Academy (China) and maintained in DMEM (Hyclone, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma, USA). 3T3-L1 cells were induced into mature adipocytes based on previous research.22 The LO2 cells were seeded into 6-well plates and treated with PA (800μmol/l) or combined with ADEs (2μg) and pcDNA-Sirt1 for 24h to establish an in vitro model. To determine the biological effect of miR-122, we first silenced miR-122 in adipocytes using a miR-122 inhibitor and then isolated exosomes from the adipocytes. Transfection was conducted using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell viability and apoptosisCell viability and apoptosis were assessed using the MTT assay and flow cytometry, respectively. For the MTT assay, LO2 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 5000 cells per well after the indicated treatment. After incubation for 24h, the MTT reagent (5mg/ml, 10μl) was added to each well and incubated for another 4h. Absorbance was measured at 490nm using a microplate reader (ThermoFisher Scientific). To evaluate apoptosis, cells were collected and stained with Annexin V and PI (5μl) for 30min and measured using a flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Germany).

Rat model and treatmentEight-week-old Sprague–Dawley rats weighing approximately 200g were obtained from Pengyue (Jinan, China). The rats were housed under a 12/12 light/dark cycle at a controlled temperature of 25°C for one week. The rats were then randomly divided into seven groups: (1) normal, (2) NAFLD, (3) NAFLD+ADEs, (4) NAFLD+inhibitor NC-ADEs, (5) NAFLD+miR-122 inhibitor-ADEs, (6) NAFLD+ADEs+AVV-NC, and (7) NAFLD+ADEs+AVV9-Sirt1. To mimic NAFLD, rats were fed with a HFHF diet (Research Diets, USA) for 8 weeks. Rats in the normal group were fed a control diet (Research Diets, USA). For treatment, rats in groups (3), (4), (5), (6), and (7) were intravenously injected with the corresponding ADEs (100μg) and AVV9 (3×1011 genome copies) once a week for 8 weeks. After treatment, the rats were fasted for 12h, anaesthetised, and euthanised. Liver tissues were collected for histological staining.

Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stainingThe collected liver tissues were dehydrated, paraffin embedded, and sectioned into 5-μm slices. The tissue samples were then rehydrated and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (Beyotime, China) following the manufacturer's instructions. Images were captured using a microscope (Leica, Germany).

Biomedical analysisBlood samples were centrifuged to collect serum. The levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total cholesterol (TC), and triglyceride (TG) in the serum were measured using a biochemical auto-analyser (Fuji Medical System, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western blottingExosomes, cells, and liver tissues were homogenised via RIPA lysis buffer to obtain total proteins. After quantification with BCA, equal amounts of proteins were loaded onto SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore, USA). The protein bands were blocked with 5% skim milk and incubated with specific primary antibodies at 4°C. The next day, the proteins were labelled with HRP-conjugated secondary anti-rabbit and anti-mouse antibodies (Abcam, USA) at room temperature for 45min, and visualised by enhanced chemical luminescence (ECL) solution (Millipore, Germany).

Quantitative PCR assayTotal RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Thermo, USA) and transcribed to cDNA using either TransScript®Green miRNA Two-Step qRT-PCR SuperMix (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China) or Revert Aid First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher, USA). qRT-PCR was performed on an ABI 7900 system (Applied Biosystems) using either TransScript®Green miRNA Two-Step qRT-PCR SuperMix (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China) or SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Thermo Scientific). Gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method and was normalised to U6 or β-actin. The primers were obtained from Tsingke (Beijing, China) as follows: miR-122 F: 5′-GCAGTGGAGTGTGACAATG-3′, R: 5′-CCAGTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTCAAACACC-3′; U6 F: 5′-CAGCACATATACTAAAATTGGAACG-3′, R: 5′-ACGAATTTGCGTGTCATCC-3′; Sirt1 (human) F: 5′-GCCTGTGCAGTGGAAGGAAAA-3′, R: 5′-GCTGTTGCAAAGGAACCATGAC-3′; Sirt1 (rat) F: 5′-TGGAAGGAAAGCAATTTTGGAAATA-3′, R: 5′-CTGCAACCTGCTCCAAGGTA-3′; β-actin (human) F: 5′-CCCCGCGAGCACAGAG-3′, R: 5′-ATCATCCATGGTGAGCTGGC-3′; β-actin (rat) F: 5′-GCCTTCCTTCCTGGGTATGG-3′, R: 5′-AATGCCTGGGTACATGGTGG-3′.

Luciferase reporter gene assayThe potential binding site of miR-122 on Sirt1 3′UTR was predicted using TargetScan (https://www.targetscan.org/vert_72/). LO2 cells were co-transfected with wild-type or mutant luciferase reporter gene vectors with miR-122 mimics. After incubation for 48hours, cells were homogenised, and luciferase activity was measured using a dual luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, USA).

StatisticsData are shown as mean±SD. Comparisons between two or multiple groups were assessed with Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SPSS 20.0 software. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

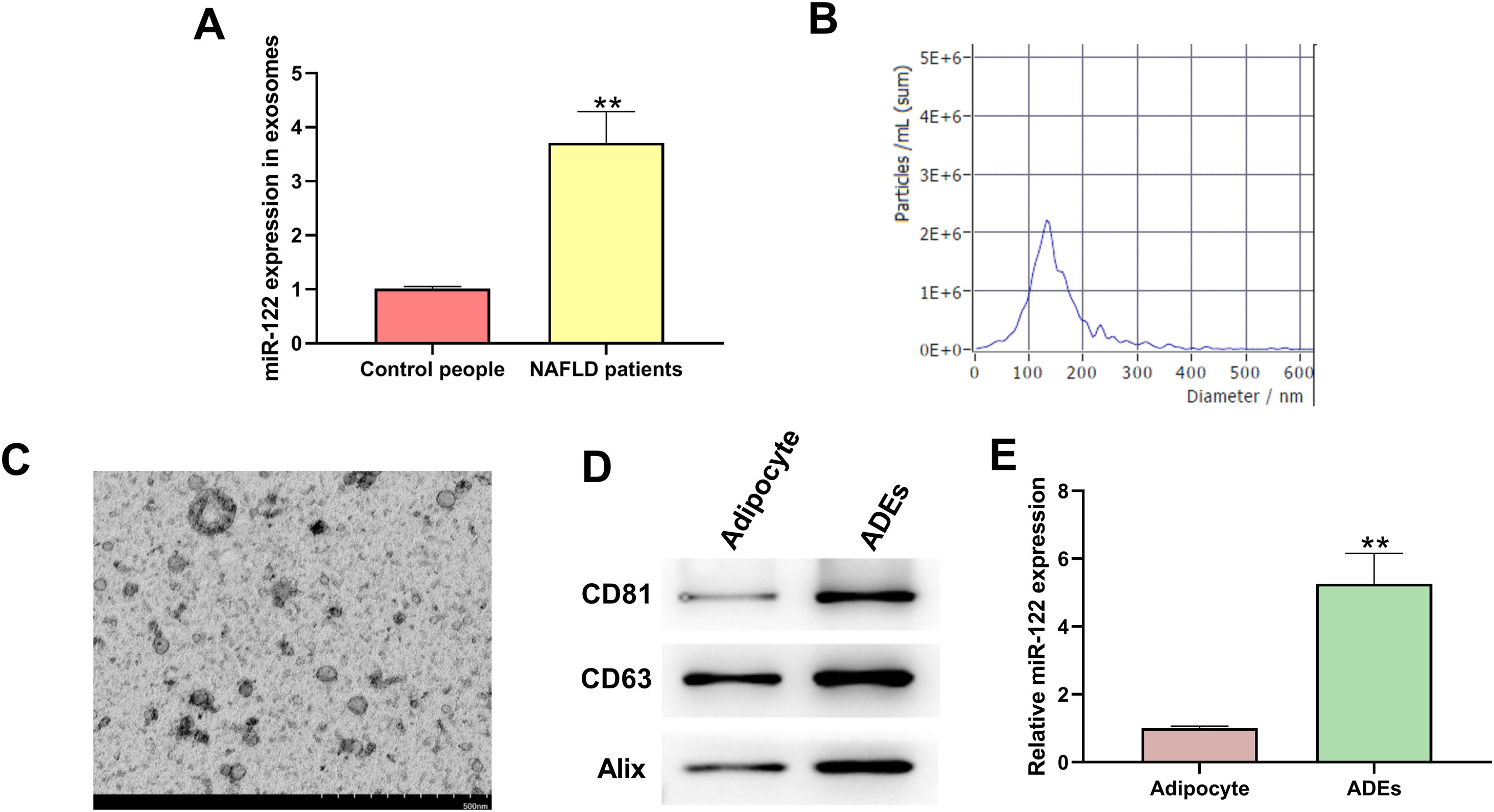

ResultsIdentification of exosomesTo determine the functions of exosomal miR-122 in NAFLD, we isolated exosomes from human blood samples and evaluated the level of miR-122. We found that miR-122 level was upregulated in the exosomes of NAFLD patients (Fig. 1A). As shown in Fig. 1B, the particle size of ADEs was distributed between 40 and 200nm, which is consistent with published articles. The morphology of ADEs was captured using TEM (Fig. 1C). Moreover, the presentation of specific biomarkers (CD81, CD63, and Alix) confirmed the successful extraction of exosomes (Fig. 1D). We also observed an elevated level of miR-122 in ADEs compared with that in adipocytes (Fig. 1E).

Identification of adipocytes-derived exosomes (ADEs). (A) PCR was applied to check miR-122 level in the exosomes of NAFLD patients. (B) NTA to check particle size of ADEs. (C) TEM to capture ADEs morphology. (D) Western blotting assay to measure expression of CD81, CD63, and Alix. (E) Relative level of miR-122 in adipocytes and ADEs. **p<0.01 vs. control people or adipocyte.

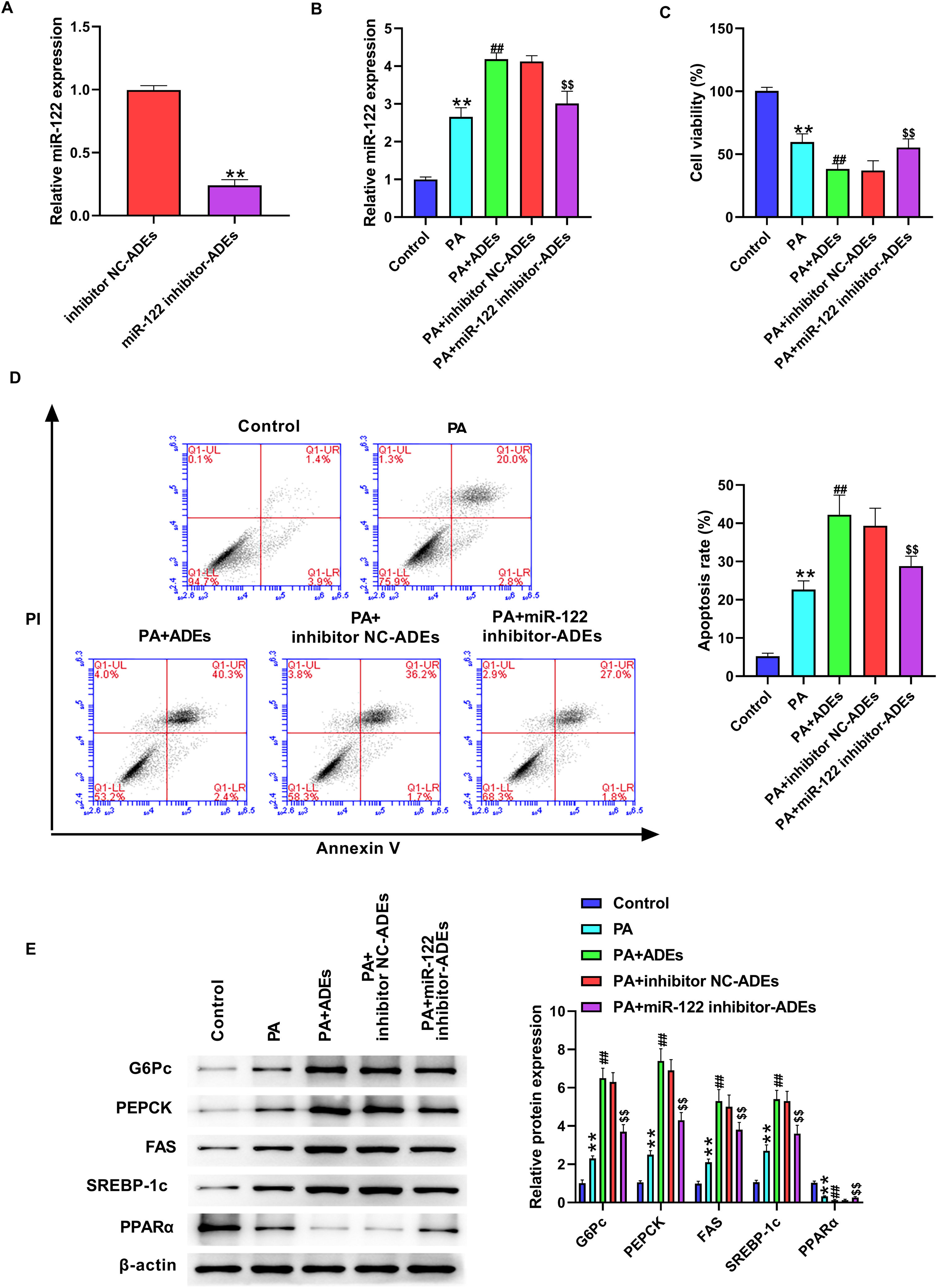

Next, we evaluated the function of ADEs miR-122 in LO2 cells. The in vitro cell model was established by PA stimulation of LO2 cells. We silenced miR-122 in adipocytes using miR-122 inhibitor and isolated exosomes from adipocytes. The level of miR-122 was decreased in isolated exosomes after transfection with miR-122 inhibitor (Fig. 1A). LO2 cells were treated with PA (800μmol/l) or combined with ADEs (2μg). Treatment with ADEs significantly elevated the level of miR-122 in LO2 cells, whereas miR-122 inhibitor-transfected ADEs reversed the level of miR-122 in LO2 cells (Fig. 2B). We observed suppressed LO2 cell viability and increased apoptosis in LO2 cells following PA stimulation (Fig. 2C and D). Treatment with ADEs further repressed LO2 viability, and knockdown of miR-122 improved cell survival caused by ADEs treatment (Fig. 2C and D). We further evaluated critical regulators of lipogenesis and glucose metabolism. PA stimulation elevated the protein levels of G6Pc, PEPCK, FAS, and SREBP-1c, as well as decreased level of PPARα, suggesting enhanced lipogenesis and gluconeogenesis (Fig. 2E). Treatment with ADEs further enhanced glucose and lipid metabolism, whereas knockdown of miR-122 in ADEs reversed these effects (Fig. 2E).

Adipocytes-derived exosomal (ADEs) miR-122 promotes glucose and lipid metabolism of human hepatocytes. (A) LO2 cells were treated with inhibitor NC-transfected ADEs (inhibitor NC-ADEs), or miR-122 inhibitor-transfected ADEs (miR-122 inhibitor-ADEs). The miR-122 level was checked by qRT-PCR. (B–E) LO2 cells were treated with PA, along with ADEs, inhibitor NC-transfected ADEs (inhibitor NC-ADEs), or miR-122 inhibitor-transfected ADEs (miR-122 inhibitor-ADEs). (B) The expression of miR-122 was checked by qRT-PCR. (C) Cell viability measured by the MTT assay. (D) Cell apoptosis measured by flow cytometry. (E) Western blotting assay to measure expression of G6Pc, PEPCK, FAS, SREBP-1c, and PPARα in LO2 cells. **p<0.01 vs. control; ##p<0.01 vs. PA; $$p<0.01 vs. PA+inhibitor NC-ADEs.

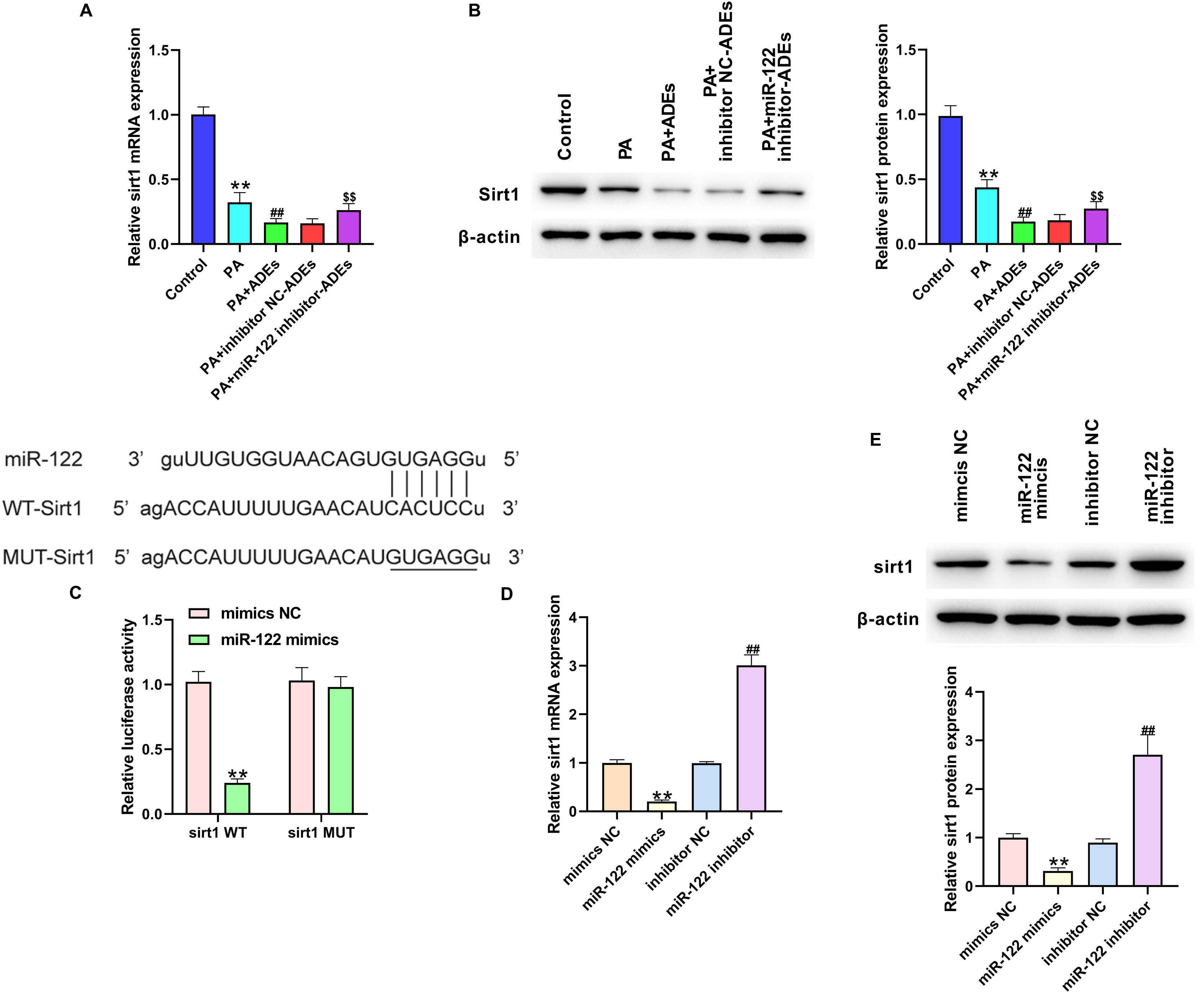

Subsequently, we explored the possible mechanisms underlying ADEs miR-122-regulated LO2 function. We found that treatment with PA and ADEs notably decreased mRNA and protein levels of Sirt1 in LO2 cells, and depletion of miR-122 reversed the expression of Sirt1 (Fig. 3A and B). Here, we investigated whether miR-122 directly targeted Sirt1 mRNA. Prediction using the TargetScan website indicated a potential binding site of miR-122 on Sirt1 3′UTR (Fig. 3C). We constructed luciferase reporter gene vectors that inserted with wild-type Sirt1 3′UTR (Sirt1 WT) or Sirt1 3′UTR sequence with a mutated miR-122 binding site (Sirt1 MUT). Results from the luciferase reporter gene assay revealed that miR-122 mimics notably suppressed the activity of Sirt1 WT rather than Sirt1 MUT (Fig. 3C), suggesting the interaction between miR-122 and Sirt1 WT. In addition, treatment with miR-122 mimics and miR-122 inhibitor directly decreased and increased Sirt1 RNA and protein levels, respectively (Fig. 3D and E).

Adipocytes-derived exosomal (ADEs) miR-122 suppresses Sirt1 expression in hepatocytes. LO2 cells were treated with PA, together with ADEs, inhibitor NC-transfected ADEs (inhibitor NC-ADEs), or miR-122 inhibitor-transfected ADEs (miR-122 inhibitor-ADEs). The mRNA (A) and protein (B) level of Sirt1 in LO2 cells was checked by qRT-PCR. (C) Luciferase activity of luciferase reporter gene vectors that inserted with wild-type Sirt1 3′UTR (Sirt1 WT) or Sirt1 3′UTR sequence with mutated miR-122 binding site (Sirt1 MUT). (D) LO2 cells were transfected with miR-122 mimics, miR-122 inhibitor, mimics NC, or inhibitor NC. The mRNA (A) and protein (B) level of Sirt1 in LO2 cells was measured by qRT-PCR. **p<0.01 vs. control or mimics NC; ##p<0.01 vs. ADEs or inhibitor NC; $$p<0.01 vs. PA+inhibitor NC-ADEs.

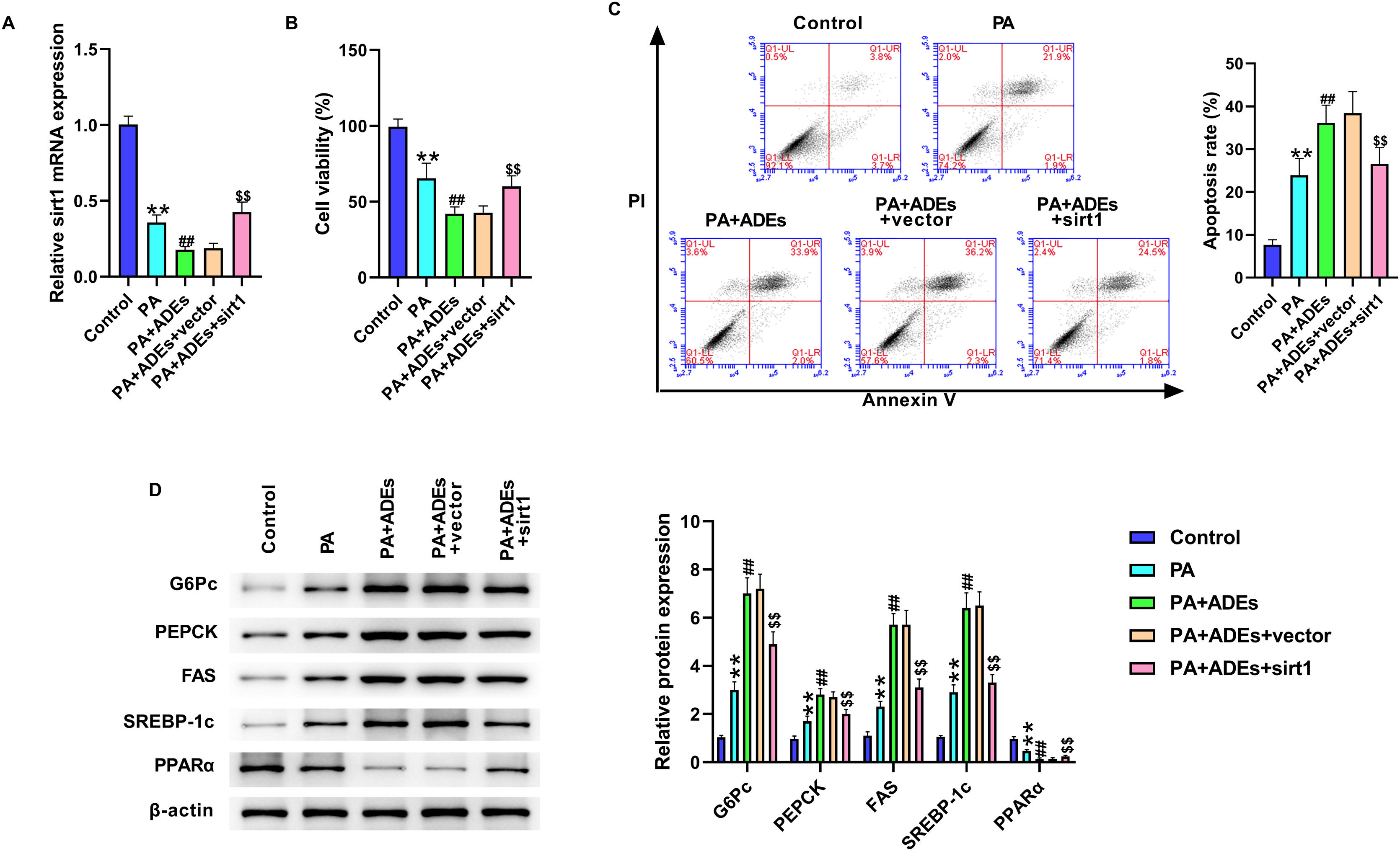

Next, we evaluated the role of Sirt1 in miR-122-regulated LO2 cells function. LO2 cells were treated with PA and ADEs, with or without Sirt1 overexpression. The results of qRT-PCR showed that Sirt1 overexpression markedly reversed the downregulation of Sirt1 induced by ADEs (Fig. 4A). Sirt1 overexpression notably elevated the suppression of cell viability under PA and ADEs treatment, simultaneously suppressing cell apoptosis (Fig. 4B and C). Furthermore, overexpression of Sirt1 suppressed PA and ADEs stimulated glucose and lipid metabolism (Fig. 4D).

Adipocytes-derived exosomal (ADEs) miR-122 promotes glucose and lipid metabolism of LO2 cells via modulating Sirt1. LO2 cells were treated with PA, along with ADEs, Sirt1 overexpression vectors and control vectors. (A) The Sirt1 level was tested using qRT-PCR. (B) Cell viability measured by MTT assay. (C) Cell apoptosis measured by flow cytometry. (D) Western blotting assay to measure expression of G6Pc, PEPCK, FAS, SREBP-1c, and PPARα in LO2 cells. **p<0.01 vs. control; ##p<0.01 vs. PA; $$p<0.01 vs. PA+ADEs+vector.

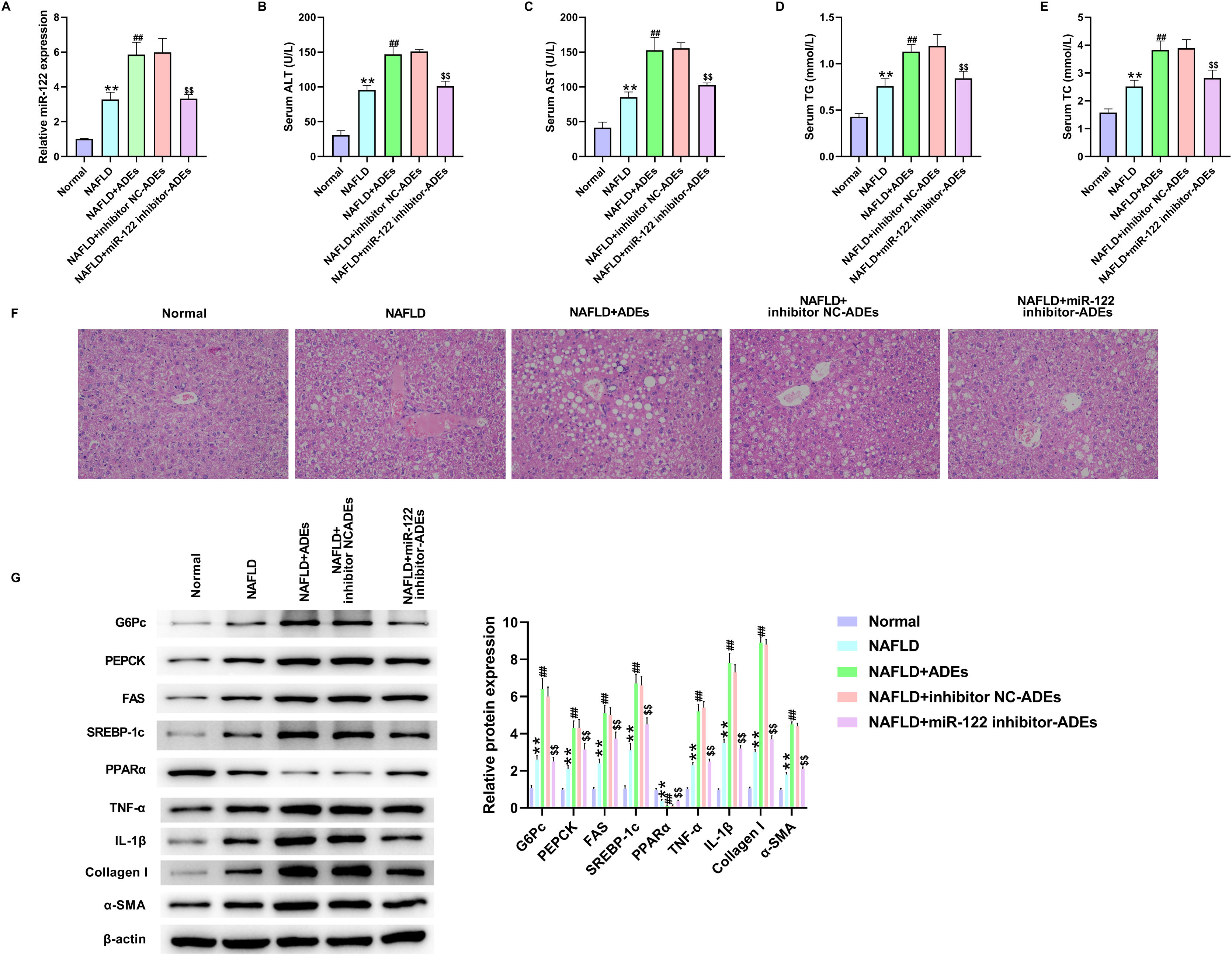

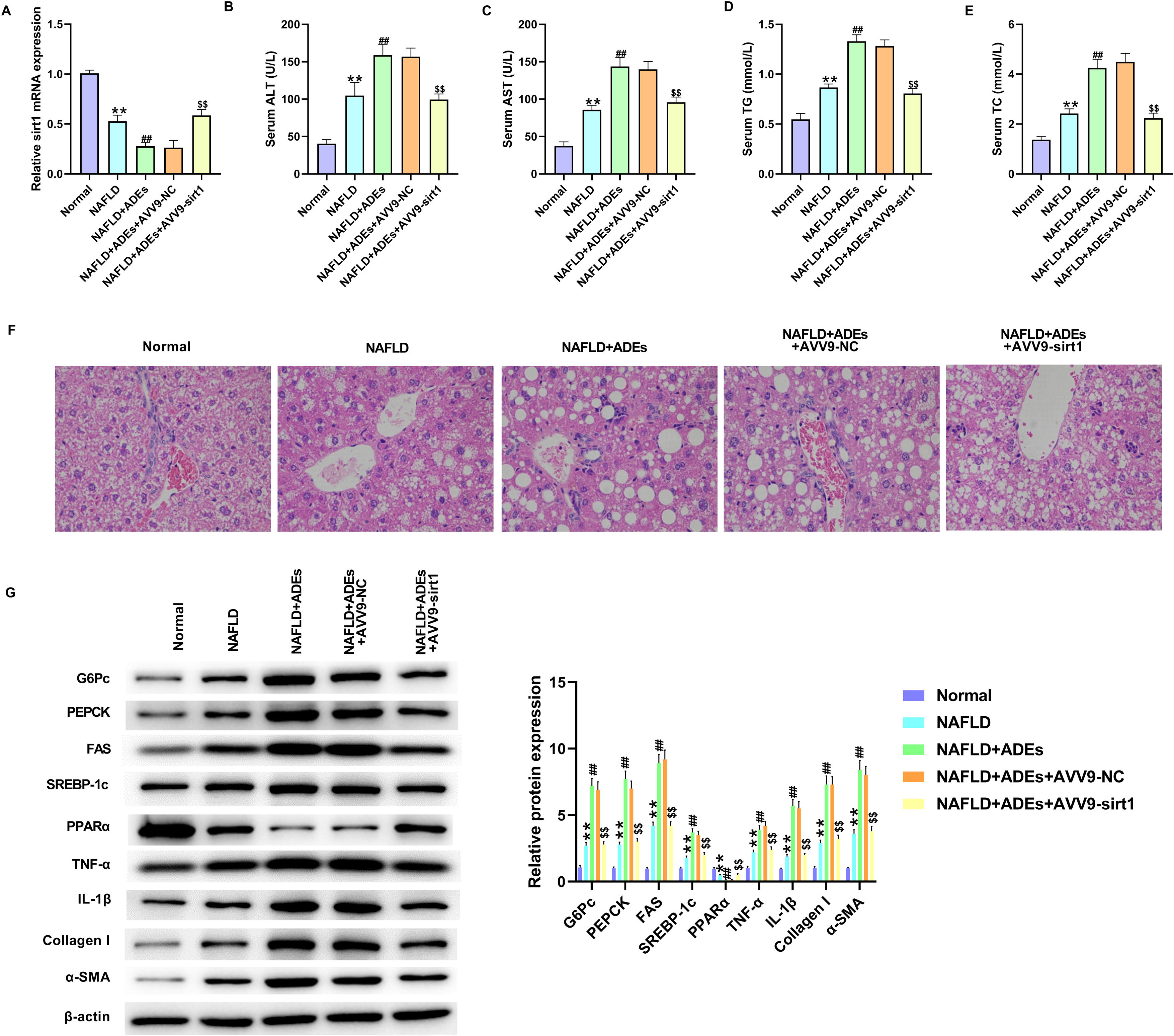

We established an in vivo NAFLD rat model to determine the role of ADEs miR-122. Exosomes were isolated from 3T3-L1 cells following transfection with miR-122 inhibitor. The NAFLD rat model was established by HFHF feeding, followed by the ADEs treatment. First, depletion of miR-122 in ADEs markedly reversed the upregulation of miR-122 induced by ADEs (Fig. 5A). Examination of serum lipid revealed elevated levels of ALT, AST, TC and TG in NALFD rats, and treatment with ADEs exacerbated serum lipid secretion (Fig. 5B–E). In contrast, depletion of miR-122 in ADEs repressed ADEs-induced serum lipid accumulation (Fig. 5B–E). H&E staining of liver tissues revealed that depletion of miR-122 alleviated ADEs-induced liver damage in NAFLD rats (Fig. 5F). Moreover, depletion of miR-122 in ADEs significantly relieved the increase in glucose and lipid metabolism, liver inflammation and fibrosis induced by ADEs in vivo (Fig. 5G). After AVV9-Sirt1 treatment, the downregulation of Sirt1 induced by ADEs was markedly reversed (Fig. 6A). Meanwhile, treatment with AVV9-Sirt1 relieved ADEs-induced serum lipid accumulation (Fig. 6B–E). In addition, H&E staining also confirmed that treatment with AVV9-Sirt1 alleviated ADEs-induced liver damage in NAFLD rats (Fig. 6F). Furthermore, the results in Fig. 6G showed that treatment with AVV9-Sirt1 notably relieved the increase in glucose and lipid metabolism, liver inflammation, and fibrosis induced by ADEs in NAFLD rats. These data revealed that ADEs miR-122 promoted in vivo liver damage and glucose and lipid metabolism via modulation of Sirt1.

Adipocytes-derived exosomal (ADEs) miR-122 promotes in vivo liver damage and glucose and lipid metabolism. An in vivo NAFLD rat model was established, rats were treated with ADEs, inhibitor NC-transfected ADEs (inhibitor NC-ADEs), or miR-122 inhibitor-transfected ADEs (miR-122 inhibitor-ADEs). (A) The expression of miR-122 was tested using qRT-PCR. The serum levels of the alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (B), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (C), triglyceride (TG) (D), and total cholesterol (TC) (E) were measured. (F) H&E staining of liver damage. (G) Western blotting assay measured expression of G6Pc, PEPCK, FAS, SREBP-1c, PPARα, TNF-α, IL-1β, Collagen I, and α-SMA in liver tissues. **p<0.01 vs. normal; ##p<0.01 vs. NAFLD; $$p<0.01 vs. NAFLD+inhibitor NC-ADEs.

Adipocytes-derived exosomal (ADEs) miR-122 promotes in vivo liver damage and glucose and lipid metabolism via modulating Sirt1. An in vivo NAFLD rat model was established, rats were treated with ADEs and AVV9-Sirt1. (A) The expression of Sirt1 was tested using qRT-PCR. The serum levels of the ALT (B), AST (C), TG (D), and TC (E) were measured. (F) H&E staining of liver damage. (G) Western blotting assay measured expression of G6Pc, PEPCK, FAS, SREBP-1c, PPARα, TNF-α, IL-1β, Collagen I, and α-SMA in liver tissues. **p<0.01 vs. normal; ##p<0.01 vs. NAFLD; $$p<0.01 vs. NAFLD+ADEs+AVV9-NC.

NAFLD is a disease that commonly occurs in patients with obesity and diabetes and is characterised by excessive lipid accumulation in theliver.3 The functions of adipose tissues have been identified beyond storing lipids and nutrients, such as secreting adipokines, inflammatory cytokines, and extracellular vehicles, to participate in abnormal metabolism.23 Adipose tissues are reported to be involved in lipid and glucose metabolism, and are correlated with NAFLD progression.24 The role of EVs in metabolic diseases, especially obesity-related diseases, has recently been explored.25,26 A recent study indicated that circulating ADEs maintains glucose homeostasis by modulating insulin resistance.27 Moreover, Koeck et al. proved that exosomes extracted from visceral adipose tissue could be internalised by liver HepG2 cells and modulate transduction of the transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) signalling, as well as facilitate NAFLD development.28 As the principal bio-active cargos, miRNAs have been widely reported to participate in the initiation and development of various diseases, such as cancers, cardiovascular diseases and metabolic diseases.29

Previous studies have reported that miR-122 is abundant in liver tissues, and abnormally increased serum level of miR-122 have been found in patients and rat NAFLD models.29–31 In particular, elevated miR-122 expression was reported to correlate with the degree of liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD.32 Therefore, miR-122 is a potential predictor of NAFLD.33–35 Nevertheless, whether adipose tissue affects hepatocytes function through exosomal miR-122 has not yet been defined. In this study, we isolated ADEs and characterised their particle size, morphology, and biomarker proteins. Our data showed that the isolated ADEs contained higher level of miR-122, and depletion of miR-122 in the isolated ADEs improved cell viability and suppressed cell apoptosis in the PA-induced in vitro model.

Adipose-derived EVs activate lipogenesis by upregulating critical lipogenic enzymes such as FASN, G6PD, and ACC under hypoxic conditions.36 In contrast, we observed that PA treatment elevated the expression of the lipogenesis-related enzymes (G6Pc, PEPCK, and SREBP-1c) and suppressed PPARα. Depletion of miR-122 in ADEs reversed this phenomenon, suggesting the suppression of lipid and glucose metabolism. Moreover, we established an in vivo rat model using a HFHF diet and determined that ADEs miR-122 promoted the serum lipid levels and liver damage, inflammation and fibrosis.

Previous studies have demonstrated downregulated hepatic Sirt1 expression in NAFLD rat model.37 Purushotham et al. found that Sirt1 depletion repressed the oxidation of fatty acids in hepatocytes.38 Moreover, Sirt1 modulates the expression of genes that correlate with cell metabolism through NAD-dependent histone deacetylation.39 Analysis of the molecular mechanisms revealed that ADEs miR-122 directly interacted with Sirt1 to suppress its expression in hepatocytes. Hence, these studies support our findings of enhanced lipid and glucose metabolism upon ADEs miR-122 treatment via modulation of Sirt1.

Our study had some limitations. The main difference between exosomes from miR-122 silenced cells and control adipocytes was not attributed solely reduced miR-122 levels. There were other cellular responses in miR-122 silenced adipocytes, and the expression of many downstream genes was altered. Further investigations are needed to determine whether downstream genes play roles in NAFLD.

ConclusionIn summary, we demonstrated that ADEs contain abundant miR-122, and modulate lipid and glucose metabolism in hepatocytes. Inhibition of miR-122 in ADEs notably alleviated liver damage in an in vivo rat NAFLD model, and improved LO2 cell viability and metabolism in an in vitro model. Mechanistically, we found that miR-122 directly interacted with the 3′UTR of Sirt1 to suppress Sirt1. Our findings suggest that ADEs miR-122 is a novel diagnostic and promising therapeutic target in NAFLD.

Ethics approval and consent to participateThe experimental protocol of our study was performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Longhai First Hospital Affiliated to Xiamen Medical College.

Consent for publicationAll the authors agree to the publication clause.

Code availabilityNone.

Availability of data and materialThe data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contributionsKai Chen designed the study; Kai Chen, Tingting Lin, Weirong Yao and Xinqiao Chen performed the research; Xiaoming Xiong and Zhufeng Huang analysed data; manuscript writing: all authors; final approval of manuscript: all authors.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no competing interests exist.

This research was supported by grants from Zhangzhou Natural Science Foundation of China (Project Number: ZZ2021J21).