Patients with liver cirrhosis who are candidates for liver transplantation must be evaluated both clinically and socially in order to obtain the optimal outcomes and avoid futile therapeutic measures. For the evaluation of the social aspects in these patients, no validated scale in Spanish is available. The SIPAT (Stanford Integrated Psychosocial Assessment for Transplantation) scale is an instrument that measures the social, family and psychological aspects in candidates for solid organ transplantation. The objective of this study is to adapt and validate an abbreviated version of the SIPAT scale in Spanish for patients with liver cirrhosis.

Material and methodsProspective observational study carried out in the Hepatology Unit of the La Fe Unversity Hospital in Valencia, by questionnaire validation methodology. To analyze the reliability of the questionnaire, the internal consistency of all variables was calculated, for variability an exploratory factor analysis, and for stability the test-retest test was carried out.

Results96 patients who were admitted for decompensated cirrhosis to the Hepatology Unit of the La Fe Hospital in Valencia between November 1, 2017 and January 31, 2017 were selected. 84% were men, the mean age was 60.01 (SD 10.12) years. In 73.2% of those admitted, the etiology of cirrhosis was alcoholic. 14.4% had a Child's stage A, 57.7% B and 27.8% C. The internal consistency of all variables reached a Cronbach's Alpha of 0.766. In the exploratory factor analysis, 6 dimensions of the questionnaire were identified that explain 84.27% of the total variability. To see the stability of the instrument, the measurement was repeated at 2 and 6 months of follow-up, obtaining in the test-retest a kappa agreement of 0.612 and 0.565 respectively.

ConclusionThe SIPAT-11 questionnaire has good psychometric characteristics in cirrhotic patients who are candidates for liver transplantation. It is easy to complete and can be administered by professionals who are not specialists in the area of Mental Health.

Los pacientes con cirrosis hepática candidatos a trasplante hepático deben ser evaluados tanto en la esfera clínica, como en la sociofamiliar para obtener buenos resultados y evitar medidas terapéuticas fútiles. Para la evaluación de la esfera social, no disponemos de una escala validada en español en este perfil de paciente. La escala SIPAT es un instrumento de medida de las esferas sociales, familiares y psicológicas en candidatos a trasplante de órgano sólido. El objetivo de este estudio es adaptar y validar una versión abreviada de la escala SIPAT (Stanford Integrated Psychosocial Assessment for Transplantation) en español para pacientes con cirrosis hepática.

Material y metodosEstudio prospectivo observacional realizado en la Unidad de Hepatología del Hospital Universitario y Politécnico la Fe de Valencia, con metodología de validación de cuestionarios. Para el análisis de la fiabilidad del cuestionario se calculó la consistencia interna de todas las variables, para la variabilidad un análisis factorial exploratorio, y para la estabilidad se realizó la prueba de test-retest.

ResultadosSe seleccionaron 96 pacientes que ingresaron por cirrosis descompensada en la Unidad de Hepatología del hospital La Fe de Valencia entre el 1 de noviembre de 2017 y el 31 de enero de 2017. El 84% fueron hombres, la edad media fue de 60.01 (DE 10.12) años. En el 73.2% de los ingresados la etiología de la cirrosis era alcohólica. Estaban en estadio A de Child el 14.4%, en el B un 57.7% y un 27.8% en el estadio C. La consistencia interna de todas las variables alcanzó una Alfa de Cronbach de 0.766. En el análisis factorial exploratorio se identificaron 6 dimensiones del cuestionario que explican el 84.27% de la variabilidad total. Para ver la estabilidad del instrumento se repitió la medición a los 2 y 6 meses de seguimiento obteniéndose en la prueba del test-retest una concordancia kappa de 0.612 y de 0.565 respectivamente.

ConclusionEl cuestionario SIPAT-11 presenta unas buenas características psicométricas en pacientes cirróticos candidatos a trasplante hepático. Es de fácil cumplimentación y puede ser administrado por profesionales no especialistas en el área de Salud Mental.

Liver cirrhosis (LC) is a chronic disease that causes 170,000 deaths per year in Europe and the incidence is increasing.1,2 In its advanced stages, when the LC becomes decompensated, it is considered a terminal disease for which the only curative treatment is liver transplant (LT). The development of complications such as hepatocellular carcinoma is a significant cause of death in these patients, but which can also be treated with LT in some cases. The natural history of the disease is characterised by an asymptomatic or “compensated” phase that leads to a phase of clinical decompensation (ascites, gastrointestinal bleeding due to portal hypertension, encephalopathy or jaundice). The development of such decompensation has a marked impact on average survival, falling from 12 years in the first phase to less than two years.3,4 A number of independent survival factors have been described, including clinical factors, such as those listed in the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score or the Child-Pugh Score, and social factors.5–7

According to data from the Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation (GODT), in the last decade, solid organ transplants have increased by 30% worldwide.8 In Spain, according to data from the Organización Nacional de Trasplantes [Spanish National Transplant Organisation], transplant activity grew by 8% in 2021 and a total of 1078 liver transplants were performed.9 Given the shortage of donor organs, candidates to be placed on the transplant waiting list must be carefully selected. This decision is made based on medical and psychosocial criteria. However, the psychosocial criteria are not as standardised as the medical criteria, and this can introduce bias in the selection of candidates and create ethical problems.10

Psychosocial problems are prevalent in patients undergoing pre-surgical assessment. For example, 76% of LT candidates have a previous history of substance abuse and 50% have poor compliance with the recommended treatments.11 Psychosocial problems have been linked to worse post-surgical outcomes, increasing the rate of hospitalisations, the percentage of infections, the rejection rate and mortality rates.12,13 There is very limited research in this field and there are no recommendations for a psychosocial measurement tool. Today, one of the most widely used tools is the Stanford Integrated Psychosocial Assessment for Transplantation (SIPAT) scale.14,15 It was designed by Maldonado et al. in 201216 and consists of 18 items that explore five domains: patient's readiness level; lifestyle; social support system; psychopathological stability; and substance abuse. It stratifies candidates into five categories: excellent; good; acceptable (consider for the transplant list, but a plan is needed to satisfactorily address identified risk factors); poor (recommend deferral of inclusion on the waiting list); and high-risk (transplant not recommended). The SIPAT scale has been validated in several countries with good results in terms of validity and reproducibility.17–19 It is a good predictor of poor post-surgical outcomes in patients identified with high psychosocial risk.20 The SIPAT has a very specific psychopathology section that is best completed by mental health experts (psychologists or psychiatrists); this limits its applicability by other healthcare professionals who are not mental health specialists.

A recent review on the subject11 recognises the lack of research in this field and recommends more in-depth analysis of psychosocial measurement tools with the aim of increasing their precision. In light of the above, the aim of this study was to adapt and validate an abbreviated version of the SIPAT scale (SIPAT-11) in patients with LC, in order to simplify it and facilitate its completion by non-mental health professionals, thereby promoting its applicability.

Material and methodsType of studyThis was an observational study with questionnaire validation methodology.

Adaptation of the SIPAT-11 questionnaireFirst, permission was sought from the authors of the questionnaire. Following the qualitative methodology, semi-structured interviews were conducted in focus groups with patients diagnosed with LC and family members. After coding, key concepts were detected and their properties and dimensions identified. The interviews were conducted by social workers with experience in this field who were the people in the first instance who adapted the SIPAT questionnaire. For the final version of the questionnaire, peer review was requested from social workers from four different hepatology units. The international scales available in the literature were also reviewed. The final version of the questionnaire was established by consensus of the entire team.21

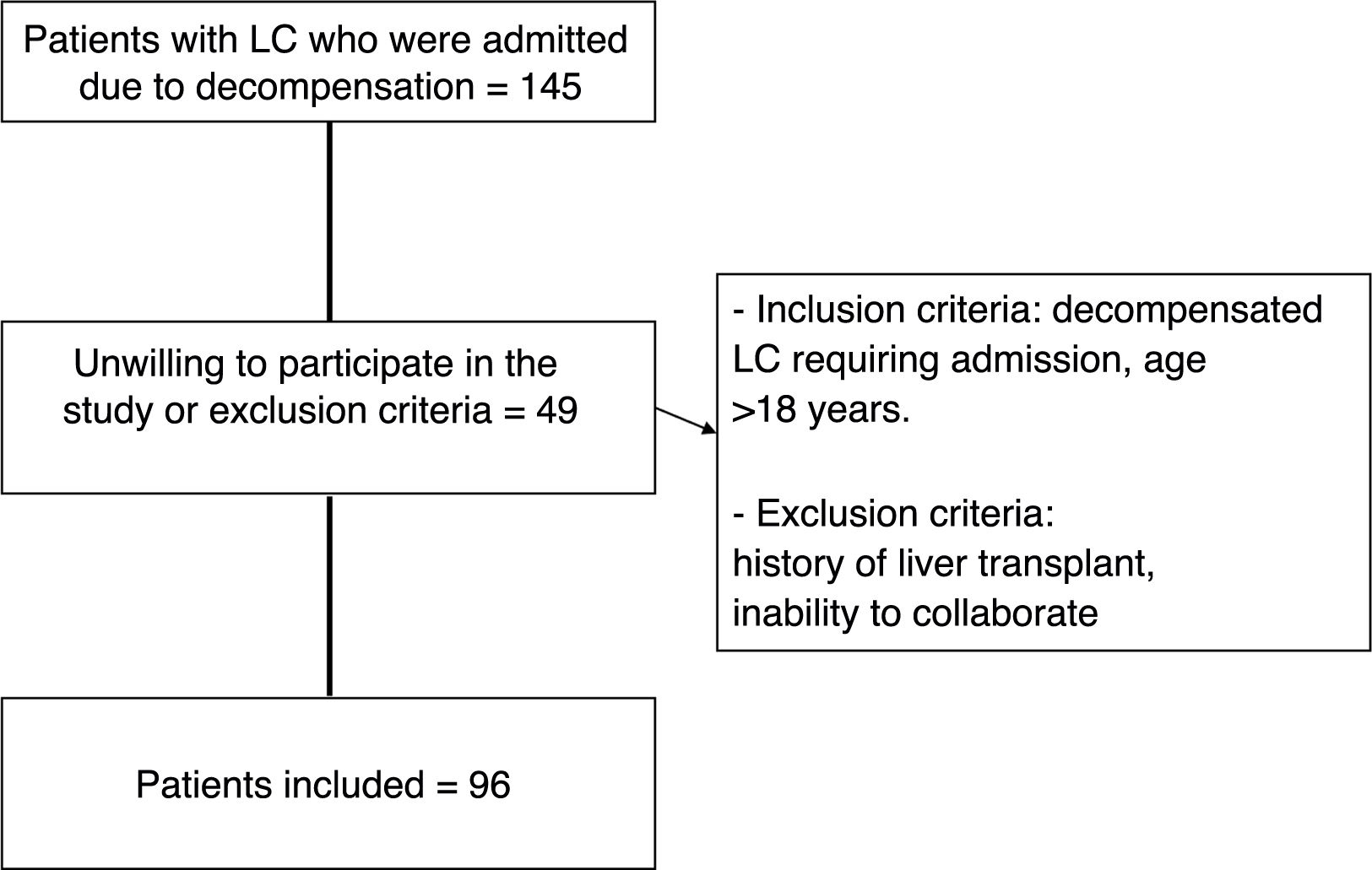

RecruitmentFor proper questionnaire validation, at least four patients are required per item.22 This study included patients diagnosed with LC who required admission to the Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe Hepatology Unit in Valencia, Spain, from 1 November 2017 to 31 January 2019.

The inclusion criteria were patients with decompensated LC of any aetiology who were over 18 years of age and who were admitted to the centre due to decompensation of their disease. Patients who had a previous history of LT, who had cognitive disturbance that made it difficult to assess their social situation, or who did not consent to take part in the study after reading the informed consent form were excluded from the study.

Construct validityThe questionnaire was completed by social workers or gastroenterology medical specialists in a maximum time of approximately one hour. The assessment was subsequently interpreted by stratifying the cases into four categories: excellent or good candidate; minimally acceptable candidate; candidate with significant identified risks; and candidate not recommended for transplant.

Subsequently, to validate the questionnaire, an exploratory factor analysis of principal components and Varimax rotation was carried out in order to identify the structure of the tool and to be able to describe the existing dimensions. The Bartlett test of sphericity and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test were performed. Maximum likelihood estimation was used in the confirmatory factor analysis. The score for each dimension was calculated by adding up the items in that dimension. The ceiling effect (number of responses with the highest possible score) and floor effect (number of responses with the lowest possible score) were also calculated.

Reliability analysisTo analyse the internal consistency of the tool, Cronbach's alpha coefficient was calculated for each of the dimensions identified in the questionnaire and for all of them together. Correlation coefficients less than 0.1 were discarded, and mean and variance were calculated if the item was eliminated. Cronbach's alpha values of 0.7 and higher were considered acceptable.

Test/re-testTo observe the stability of the questionnaire over time, the measurement was repeated after two and six months, calculating the kappa agreement index. To interpret the reproducibility of questionnaires, agreement values above 0.4 are considered adequate.22

Descriptive analysisA descriptive analysis was performed in which categorical variables were summarised in terms of absolute frequency and percentages, and quantitative variables were summarised in terms of mean and standard deviation (SD), median and interquartile range. All tests were performed using a two-tailed approach. A value of P&#¿;<&#¿;.05 was considered significant. The ceiling effect and the floor effect were calculated if more than 15% of patients obtained the lowest or highest possible scores.

For statistical analysis, the program BM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York, USA) and the program Epidat 4.2, Consellería de Sanidade, Xunta de Galicia [Ministry of Health, Regional Government of Galicia], in collaboration with the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO/World Health Organization [WHO]) were used.

Ethical considerationsThis study was approved by the Hospital Universitario La Fe Independent Ethics Committee in Valencia (registration number 2017/0620). All participants signed an informed consent form. The project was developed in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Guidelines for Ethical Review of Epidemiological Studies, European and Spanish regulations on biomedical research, and European and Spanish regulations on personal data protection (the European General Data Protection Regulation [2016/679; GDPR-2016] and Spanish Organic Law 3/2018, of 5 December, on Personal Data Protection and Guarantee of Digital Rights [LOPDP-2018]).

The investigators signed a confidentiality commitment, and specific measures were adopted to maintain data integrity and safety and prevent access by third parties to any identified or identifiable personal data. No publication or report derived from the study will use or contain identified or identifiable data or images.

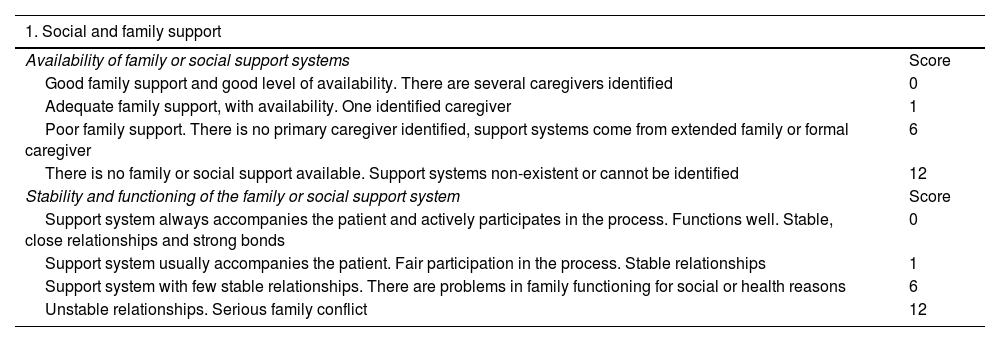

ResultsThe SIPAT questionnaire consists of 18 items with a score of 0–120 points. For the SIPAT-11 questionnaire, we removed the psychopathology items and separated the environment from the social support domain, adding the type of health coverage and the financial situation to the housing arrangements. The SIPAT-11 questionnaire was divided into four sections in total: socio-family support; lifestyle; adaptation to the environment; and readiness/coping. It consists of 11 items in total, with a score of 0–122. The higher the score, the greater the psychosocial risk. Patients are classified by total score as follows: 0–4 points, no social risk (excellent candidate); 5–9 points, minimal social risk factors (included on the transplant list, but a follow-up plan is made); 10–13 points, significant social risk (inclusion on the transplant list is deferred); and more than 14 points, high social risk (contraindicates transplant) (Table 1).

SIPAT-11 Scale.

| 1. Social and family support | |

|---|---|

| Availability of family or social support systems | Score |

| Good family support and good level of availability. There are several caregivers identified | 0 |

| Adequate family support, with availability. One identified caregiver | 1 |

| Poor family support. There is no primary caregiver identified, support systems come from extended family or formal caregiver | 6 |

| There is no family or social support available. Support systems non-existent or cannot be identified | 12 |

| Stability and functioning of the family or social support system | Score |

| Support system always accompanies the patient and actively participates in the process. Functions well. Stable, close relationships and strong bonds | 0 |

| Support system usually accompanies the patient. Fair participation in the process. Stable relationships | 1 |

| Support system with few stable relationships. There are problems in family functioning for social or health reasons | 6 |

| Unstable relationships. Serious family conflict | 12 |

| 2. LIFESTYLE | |

|---|---|

| Appropriate lifestyle (diet, exercise, smoking, etc.) | Score |

| Healthy lifestyle habits. Able to modify and sustain needed healthy changes | 0 |

| Adequate lifestyle, although some guidance may be required to reduce risks. Accepts recommendations, wants to change | 1 |

| The patient has unhealthy habits. Only accepts changes after much insistence from the family or medical team | 4 |

| Totally inappropriate lifestyle. Reluctant to change | 10 |

| Alcohol use | Score |

| No alcohol use | 0 |

| Moderate or occasional alcohol use. Stopped as soon as they learned of their illness | 1 |

| Heavy alcohol use. Continued to use alcohol after being diagnosed or had a relapse after stopping | 8 |

| Active use. History of extreme and prolonged abuse. Only stops using when their state of health is seriously affected | 14 |

| Illicit substance use. Abuse of prescribed substances | Score |

| No substance use | 0 |

| Mild/moderate substance use. Stopped as soon as they learned of their illness. Without specialised help | 1 |

| Heavy substance use. Continued to use after being diagnosed or had a relapse after stopping. Has been or is being monitored by addictive behaviour unit | 8 |

| Active use. History of extreme and prolonged abuse. Multiple relapses. Only stops using due to hospital admission or when their health status is seriously affected | 14 |

| 3. APPROPRIATENESS OF ENVIRONMENT | |

|---|---|

| Housing | Score |

| Permanent and adequate housing. It has basic services. Adequate housing arrangement | 0 |

| Stable housing arrangement. It has basic services. Arrangement is not entirely optimal | 1 |

| Temporary housing arrangement, or sub-optimal living conditions, or lack of some basic service | 4 |

| Homeless. Lives on the street, with no possibility of access to housing | 12 |

| Financial situation | Score |

| No financial problems. Can meet basic needs and extra unexpected expenses without difficulty. Has no unaffordable debts. Situation stable | 0 |

| Basic needs covered. Moderately stable situation | 1 |

| Basic needs covered, although with some precariousness and financial dependence (on social services, food banks or other organisations) | 4 |

| Lack of income or resources for subsistence. Financial situation highly precarious | 10 |

| Health coverage and pharmaceutical benefits | Score |

| Patient covered by the healthcare system in his or her own right. Free access to medication or no financial difficulties in acquiring medication | 0 |

| Patient with temporary health coverage or no coverage, but with the possibility of being accredited in the public system. Access to medication without any difficulty | 1 |

| Patient without health coverage by right, but with the possibility of signing a healthcare agreement or accessing accreditation | 4 |

| Patient without health coverage or right to financing for medication. There is no possibility of accreditation in the public system | 8 |

| 4. READINESS/COPING | |

|---|---|

| Knowledge and understanding of the medical process (cause of the illness) | Score |

| Excellent understanding on the part of patient and caregivers. High degree of self-directed learning | 0 |

| Good knowledge of the process, with some gaps | 1 |

| Modest or superficial knowledge despite the information provided or years of illness | 4 |

| Poor understanding: no knowledge of the process, extreme denial or obvious indifference | 8 |

| Willingness/desire to receive help or make changes | Score |

| Highly motivated patient directly involved in the process. Proactive attitude | 0 |

| Adequate motivation and involvement in the process. Participatory attitude | 1 |

| Appears ambivalent, only passively involved in the process. Willingness uncertain | 4 |

| Complete refusal to receive treatment or follow guidelines. The family or medical team appears more interested in the process than the patient does | 8 |

| Adherence to medical and pharmacological treatments | Score |

| Patient directly involved in his/her care. Always complies with instructions. Excellent self-care ability. Able to prepare and administer medication, as well as manage visits | 0 |

| Usually takes the initiative in caring for their illness, although they may require help in administering medications. Good self-care ability, although asks for help from the caregiver | 1 |

| Partial non-compliance with treatments. Requires persuasive efforts from the family or the healthcare team for correct adherence or only compliant temporarily after the development of complications | 8 |

| History of complete lack of adherence to treatment or refusal to continue treatment, despite the negative impact on the illness | 14 |

| Patient classification | |

|---|---|

| No social risk | 0 to 4 points |

| Minimum social risk factors | 5 to 9 points |

| Significant social risk | 10 to 13 points |

| High social risk | 14 points or more |

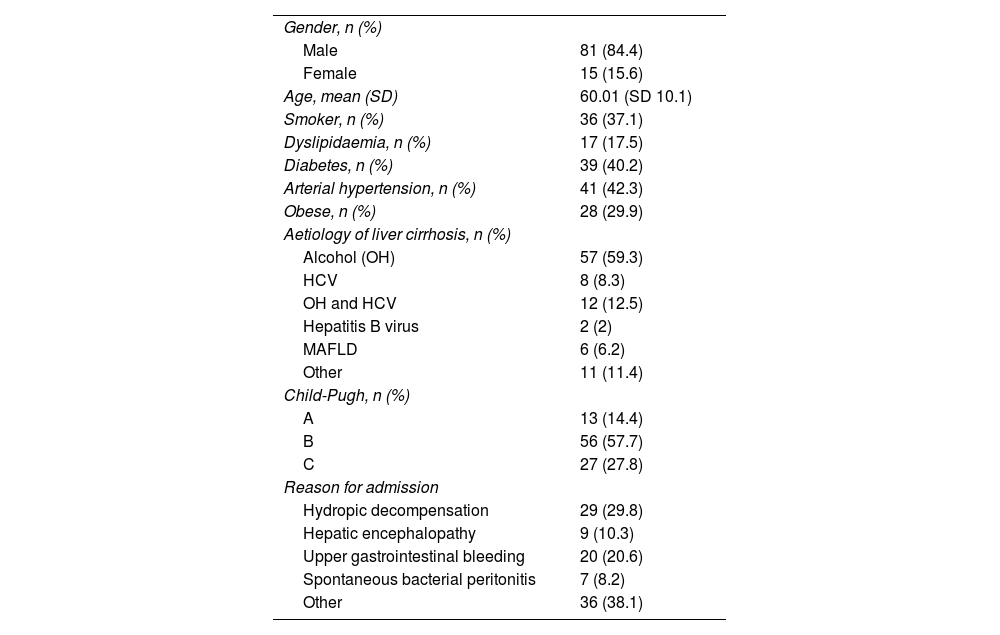

In total, 96 patients requiring admission were included (Fig. 1). Demographic and liver disease-related characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the population (n&#¿;=&#¿;96).

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 81 (84.4) |

| Female | 15 (15.6) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 60.01 (SD 10.1) |

| Smoker, n (%) | 36 (37.1) |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 17 (17.5) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 39 (40.2) |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 41 (42.3) |

| Obese, n (%) | 28 (29.9) |

| Aetiology of liver cirrhosis, n (%) | |

| Alcohol (OH) | 57 (59.3) |

| HCV | 8 (8.3) |

| OH and HCV | 12 (12.5) |

| Hepatitis B virus | 2 (2) |

| MAFLD | 6 (6.2) |

| Other | 11 (11.4) |

| Child-Pugh, n (%) | |

| A | 13 (14.4) |

| B | 56 (57.7) |

| C | 27 (27.8) |

| Reason for admission | |

| Hydropic decompensation | 29 (29.8) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 9 (10.3) |

| Upper gastrointestinal bleeding | 20 (20.6) |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 7 (8.2) |

| Other | 36 (38.1) |

HCV: hepatitis C virus; MAFLD: metabolic associated fatty liver disease; OH: alcohol.

Regarding the mean values obtained in each question of the questionnaire, for the area of social support, the mean score for availability was 1.7 (SD 2.5) and for stability, 1.3 (SD 2.3). Lifestyle had a mean score of 1.7 (SD 2), alcohol use 3.5 (SD 4.6) and other drug use 0.2 (SD 1.2). Housing had a mean score of 0.4 (SD 0.9), financial situation 0.7 (SD 1) and coverage 0.02 (SD 0.1). Finally, in relation to readiness or coping with one's own illness, knowledge of the illness obtained an average of 1.5 (SD 1.7) points, motivation (desire) 1.7 (SD 1.7) and compliance with treatment 1.7 (SD 2.5).

When classifying patients according to the total score for the questionnaire, they were stratified as follows: no social risk n&#¿;=&#¿;26 (27.9%); minimum social risk n&#¿;=&#¿;22 (22.9%); significant social risk n&#¿;=&#¿;11 (11.5%); and high social risk n&#¿;=&#¿;37 (38.5%).

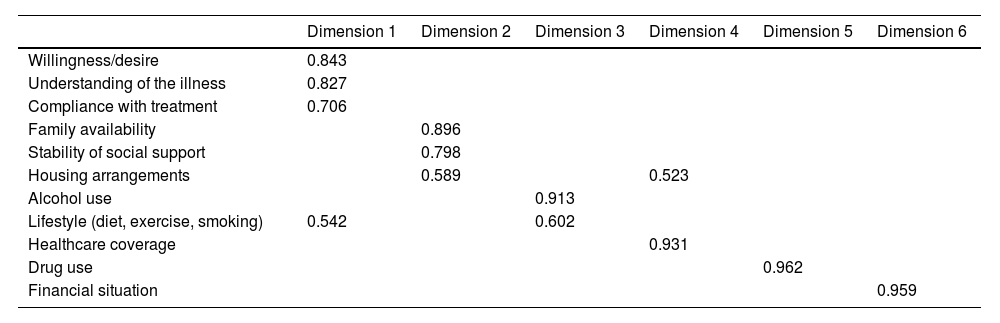

Validation of the questionnaireThe exploratory factor analysis identified six dimensions of the questionnaire accounting for 84.27% of the total variability (21.38%, 18.35%, 13.05%, 10.93%, 10.92% and 9.62%, respectively for each dimension). The values for each of the six dimensions are shown in Table 3. Dimension 1 corresponds to the patient's level of readiness and coping with the illness; dimension 2 encompasses the social support system; dimension 3 includes the patient's lifestyle: alcohol use, diet, exercise and smoking (these last three factors overlap with dimension 1); dimension 4 describes the environment in which the patient lives (type of housing, medical insurance) (the section on housing arrangements also overlaps with dimension 2); dimension 5 applies to the use of other drugs; and dimension 6 includes the patient's financial situation. All of them showed loads greater than 0.4, the expected figure in order for each dimension to perform as a differentiated factor.

Exploratory factor analysis of the SIPAT-11 questionnaire with the rotated component matrix.

| Dimension 1 | Dimension 2 | Dimension 3 | Dimension 4 | Dimension 5 | Dimension 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willingness/desire | 0.843 | |||||

| Understanding of the illness | 0.827 | |||||

| Compliance with treatment | 0.706 | |||||

| Family availability | 0.896 | |||||

| Stability of social support | 0.798 | |||||

| Housing arrangements | 0.589 | 0.523 | ||||

| Alcohol use | 0.913 | |||||

| Lifestyle (diet, exercise, smoking) | 0.542 | 0.602 | ||||

| Healthcare coverage | 0.931 | |||||

| Drug use | 0.962 | |||||

| Financial situation | 0.959 |

The floor effect percentage was 27.1% and the ceiling effect, 38.5%.

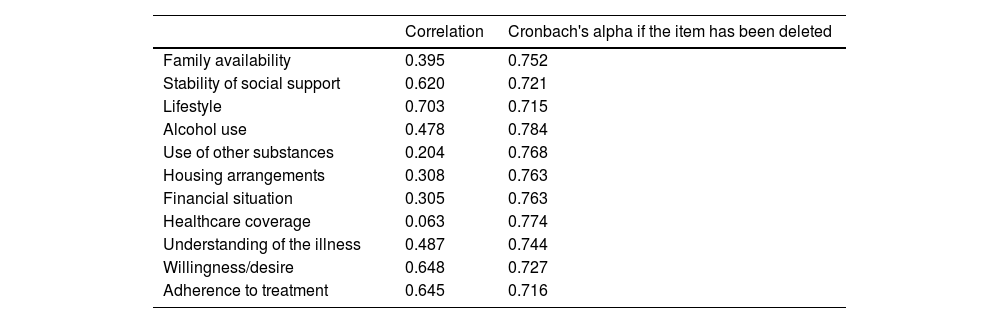

For the reliability analysis, the internal consistency of all variables was calculated, yielding a Cronbach's alpha of 0.766. Table 4 shows the correlations and Cronbach's alpha for each question in the questionnaire.

Correlations and Cronbach's alpha for each question in the questionnaire.

| Correlation | Cronbach's alpha if the item has been deleted | |

|---|---|---|

| Family availability | 0.395 | 0.752 |

| Stability of social support | 0.620 | 0.721 |

| Lifestyle | 0.703 | 0.715 |

| Alcohol use | 0.478 | 0.784 |

| Use of other substances | 0.204 | 0.768 |

| Housing arrangements | 0.308 | 0.763 |

| Financial situation | 0.305 | 0.763 |

| Healthcare coverage | 0.063 | 0.774 |

| Understanding of the illness | 0.487 | 0.744 |

| Willingness/desire | 0.648 | 0.727 |

| Adherence to treatment | 0.645 | 0.716 |

To evaluate the stability of the tool, the questionnaire was repeated at two and six months' follow-up, with the test-retest yielding a kappa agreement of 0.612 and 0.565, respectively.

DiscussionThis study adapted and validated an abbreviated version of the SIPAT integrated psychosocial risk scale in patients with LC who were candidates for transplant. The SIPAT-11 scale has good internal consistency, is reproducible and does not require the person completing it to be a mental health expert, which makes it more accessible to other healthcare professionals.

The SIPAT-11 scale was validated in 96 patients, which constitutes an adequate sample size for the 11 items that make up the questionnaire.22 The evaluation was carried out prospectively, unlike the original validation of the SIPAT by Maldonado in 2012,16 the Italian validation18 or the heart transplant version,23 which were carried out retrospectively to shorten the time for data collection. This could constitute a bias in the comparability of the studies, although, as pointed out by their authors, any bias is minimised by the good quality of the records.

Our sample was made up mainly of males in their forties and fifties, as were the samples in Maldonado's validation16 and in the validations carried out in Thailand,17 Italy18 and Barcelona (Spain).19 With regard to the clinical characteristics of the patients in our case, the percentage of patients with hypertension or diabetes is slightly higher than that reported in the validation for heart transplant carried out in Los Angeles (USA).23 We only included patients with advanced liver disease for the validation of the questionnaire, the vast majority of which were alcohol-related compared to the 20% referred to in the validation by Maldonado.16 The published SIPAT validations also included other solid organ transplant candidates such as heart, kidney and lung.17–19 These differences will have to be taken into account when comparing results, as patients with heart, kidney or lung disease may not have the same psychosocial characteristics as patients with liver disease. We did not find any description of the staging of cirrhosis or the reason for hospital admissions in other studies.

When analysing the stratification of patients according to the overall SIPAT-11 score, we found 27.9% of excellent candidates for transplant versus 38.5% of candidates with high social risk. This rate is similar to the series published by Vandenbogaart in patients with heart disease,23 but is different from the SIPAT validations carried out in Italy, Thailand, Barcelona and California, where around 5% were excellent candidates and cases of low or medium social risk predominated. These inconsistencies could be due to population differences or the type of organ transplanted. It is reported that liver or heart transplant patients have higher scores in the SIPAT compared to kidney or lung transplant patients.17,20

Regarding the characteristics of the questionnaire, the exploratory factor analysis identified six dimensions of the SIPAT-11 that performed as differentiated factors. The original SIPAT questionnaire has five dimensions because, unlike SIPAT-11, it does not include the type of housing, health coverage and financial situation. In contrast, the SIPAT-11 does not include the psychopathology assessment. This could be a problem for patients with mental illness, but could be controlled with specific questionnaires or referral to a psychiatrist or psychologist if risk factors are detected. In the vast majority of dimensions, correlations above 0.7 were achieved; better than those described in the Thai validation, which are around 0.417 and similar to the validation by López-Lazcano et al.19 The internal consistency of the questionnaire in our case exceeds a Cronbach's alpha of 0.7, which is the figure recommended for considering the reliability of the tool to be acceptable. Other validations reflect similar reliability indices.17,19 To determine the stability of the questionnaire over time, it was repeated at two and six months; the kappa agreement index exceeded 0.40, which is the minimum level appropriate to consider them reproducible.24 In the six-month measurement, the kappa index dropped to 0.56, meaning that the SIPAT-11 questionnaire loses reproducibility over time. This is logical given the time passed and the possible interacting factors in the psychosocial risk of each person. We did not find any analysis of test/re-test agreement in other published validations.

One of the limitations of our study is that the tool was only validated in patients with chronic liver disease. In future studies, the performance of the SIPAT-11 should be analysed in other solid organ transplant candidates. Our study was conducted in a population that required hospital admission due to clinical decompensation, which could lead to bias. In future studies, it would be interesting to study this assessment tool in the outpatient population. In our case, the questionnaire was completed by social workers and gastroenterologists, but we did not analyse interobserver variability. However, it was analysed in other validations, obtaining good results in the intraclass correlation coefficient.16–19,23 We did not determine the predictive value of the SIPAT-11 questionnaire regarding variables such as mortality, admission rate or transplant outcomes, which should be analysed in future studies. Maldonado et al. demonstrated that although the SIPAT questionnaire did not correlate with mortality, a higher score was associated with a higher rate of transplant rejection (HR 0.15), hospitalisation (HR 0.29), infections (HR 0.16), psychiatric decompensation (HR 0.19) and failures in the social support system (HR 0.70), without finding any differences between the different types of solid organs transplanted.20

In conclusion, the SIPAT-11 questionnaire has good psychometric characteristics in cirrhosis patients who are candidates for LT. It is easy to complete and can be administered by non-mental health professionals. Future studies should analyse how it performs in other populations and in different diseases susceptible to organ transplant, and determine whether or not it correlates with outcome variables.