To know the transmission patterns of the acute infection by the hepatitis C virus at a time when we are close to its elimination.

Patients and methodsA prospective descriptive clinical-epidemiological study of cases of acute HCV infection diagnosed between 2016 and 2020 was carried out in a reference hospital in the island of Gran Canaria.

ResultsTwenty-two cases of acute HCV were diagnosed (10 primary infections and 12 reinfections). There was an increase in the incidence from 0.6 in 2016 and 2017 to 2.3 cases per 100,000 inhabitants in 2020. The median age was 46 years. From these, 77.3% were men and 68.2% were HIV-positive. According to the risk factors, 54.5% had high-risk sexual practices, 83.3% were men who had sex with men (70% with a concomitant STI), 31.8% were drug users, 9.1% were women with neuropsychiatric disorders, and one woman (4.5%) had a previous surgical intervention. There were thirteen patients (40.9%) who presented symptoms and eleven out of the thirteen patients who were asymptomatic were HIV-positive.

ConclusionsAn increase in incidence was observed in the last years of the study and the main route of infection was high-risk sexual practice, mainly in men who have sex with men and who are HIV positive. Cases related to unsafe sex in other non-HIV groups are probably under-diagnosed. Microelimination strategies may not be sufficient to diagnose these cases, so in order to achieve elimination of the HCV the best strategy would be a population-based screening.

Conocer los patrones de transmisión de la infección aguda por el virus de la hepatitis C (VHC) en un momento en que estamos próximos a su eliminación.

Pacientes y métodosSe realizó un estudio clínico-epidemiológico descriptivo prospectivo de los casos de infección aguda por VHC diagnosticados entre los años 2016 y 2020 en un hospital de referencia de la isla de Gran Canaria.

ResultadosSe diagnosticaron 22 casos de infección aguda (10 primarios y 12 reinfecciones), observándose un incremento de incidencia de 0,6 en 2016 a 2,3 casos/100.000 habitantes en el año 2020. La mediana de edad fue de 46 años. El 77,3% eran hombres y el 68,2% eran VIH-positivos. El 54,5% mantenían relaciones sexuales de riesgo; el 83,3% eran hombres que mantenían sexo con hombres (el 70% con otra infección de transmisión sexual concomitante); el 31,8% eran consumidores de drogas, el 9,1% tenían trastornos neuropsiquiátricos y una mujer (4,5%) tuvo una intervención quirúrgica previa. El 40,9% de pacientes presentaron síntomas, y de los 13 asintomáticos, el 84,6% eran VIH-positivos.

ConclusionesObservamos un aumento de incidencia en los últimos años del estudio, y la principal vía de contagio fue tener relaciones sexuales de riesgo, principalmente en hombres que mantienen sexo con hombres y que son VIH-positivo. Los casos en personas no-VIH con relaciones sexuales no protegidas están, probablemente, infradiagnosticados. Las estrategias de microeliminación podrían ser insuficientes para diagnosticar estos casos, por lo que para conseguir la eliminación del VHC la mejor estrategia podría ser el cribado poblacional.

In 2016, the WHO set the goal to eliminate hepatitis C worldwide by 2030.1 In Spain, a Strategic Plan2 was designed with several courses of action including, among others, understanding the epidemiological characteristics of patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, in order to try to reduce the incidence and promote early diagnosis in priority populations, in which the infection is more prevalent, through micro-elimination programmes.

Knowledge of the transmission patterns of the hepatitis C virus is hampered by the silent course of the acute infection in most cases. In the largest population-based study conducted in Spain to date3 a change in the transmission patterns of the infection has been observed in recent years, with an increase in cases of sexual transmission, mainly in men who have sex with men. In Spain, most studies of acute infection have focused on the description of nosocomial outbreaks4–7 or outbreaks in HIV-positive patients,8–10 and the few published population studies were carried out before 2016, when the Strategic Plan for Elimination began.3,11,12 In our district, in a study conducted more than a decade ago12 the diagnosed cases of acute infection occurred mainly in the healthcare setting and in the population with intravenous drug addiction (there was only one case in a patient with HIV infection). At a time when we are close to achieving the goal of elimination, it is important to understand whether transmission continues to occur in these groups, or if there are other patterns that can help us find out if prevention strategies are working. For this reason, we have carried out a clinical-epidemiological study of all cases of acute infection by the hepatitis C virus diagnosed in the last five years.

Patients and methodsA prospective descriptive study was carried out of all cases of acute hepatitis C virus infection that were diagnosed in a reference hospital on the island of Gran Canaria, which cares for hospitalised people and people from primary care and social health centres belonging to our health district (population of approximately 342,000 people over 14 years of age), from January 2016 to December 2020.

Cases of acute primary infection were diagnosed by seroconversion of specific IgG antibodies and detection of virus RNA by gene amplification test (Cobas Amplicor-Roche or Panther-Hologic), and reinfection by detection of virus RNA in patients with acute primary infection that was previously cured with or without alteration of liver enzymes. In addition, the viral genotype was determined by rt-PCR (Abbott Molecular).

The following clinical-epidemiological and laboratory data were collected: age, sex, transmission risk factor, HIV infection status, presence of other concomitant sexually transmitted infections, clinical manifestations, laboratory abnormalities, treatment and evolution. In the event of diagnosis, information was collected on the possible risk factors in the last three months and these were categorised as sexual, nosocomial, use of inhaled and/or injected drugs and others (tattoos, piercings…).

The study was approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee: 2020-463-1.

ResultsDuring the study period, 22 cases of acute hepatitis C virus infection were diagnosed (two in 2016, two in 2017, five in 2018, five in 2019 and eight in 2020), 10 (45.4%) of which were primary infections and 12 reinfections. The annual incidence increased from 0.6 cases per 100,000 inhabitants in the years 2016 and 2017 to 2.3 cases in the year 2020.

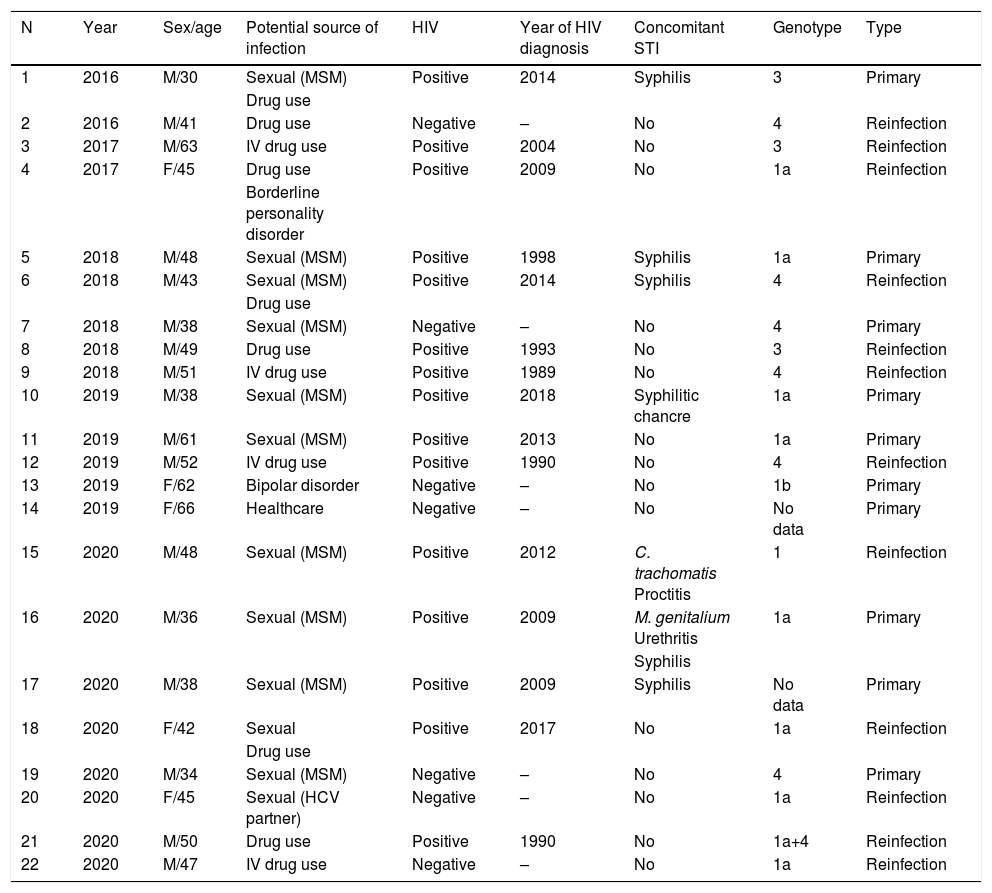

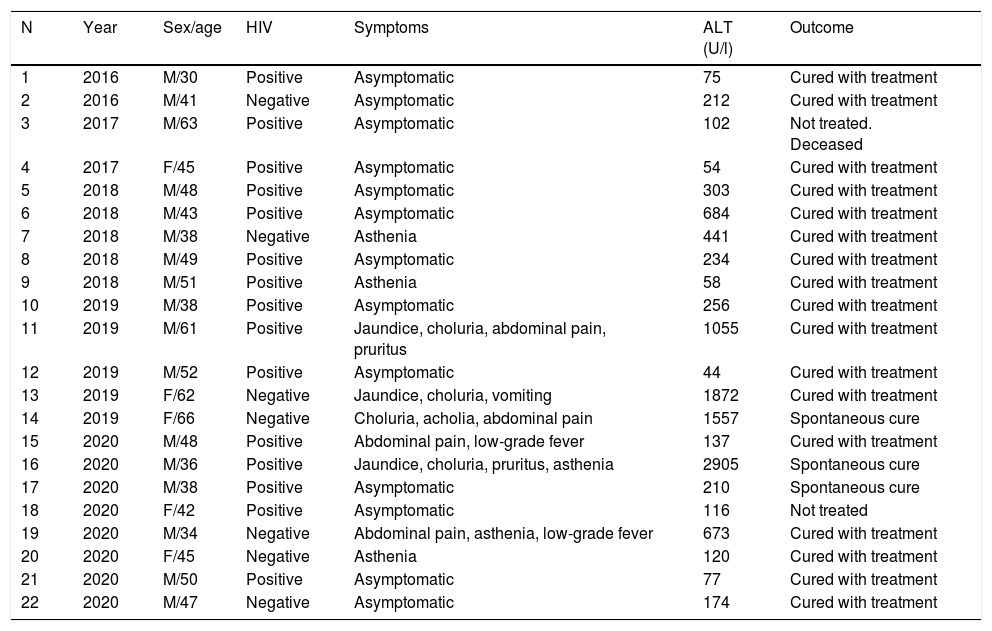

Table 1 shows the epidemiological characteristics of all cases. Seventeen (77.3%) patients were men and the median age was 46 (range 30–66) years. Fifteen (68.2%) patients were HIV-positive, all with a known prior diagnosis of hepatitis. In relation to the transmission risk factor, 12 (54.5%) had unprotected sexual relations, in some cases associated with the use of recreational drugs, of which 10 (83.3%) were men who had sex with men, and also seven (70%) had another concomitant sexually transmitted infection; another seven (31.8%) patients used inhaled and/or injected drugs, two (9.1%) were women seen at the Mental Health Unit for neuropsychiatric disorders; and lastly, one woman (4.5%) had a history of surgery in the previous two months. Table 2 presents the clinical characteristics of the patients. Only nine (40.9%) patients presented with clinical symptoms. Of the 13 asymptomatic patients, 11 (84.6%) were HIV-positive and were diagnosed with hepatitis C in an annual routine analysis that is systematically performed on these patients, and the other two were male drug users: one was diagnosed when he went to the emergency department due to an infection in his foot into which he injected heroin, and the other at a detox centre where he went for a relapse of addiction in the months previous. 73.3% (11 patients) of those infected with HIV were asymptomatic, compared to 28.6% (two patients) of non-HIV patients.

Epidemiological characteristics of patients diagnosed with acute hepatitis C virus infection.

| N | Year | Sex/age | Potential source of infection | HIV | Year of HIV diagnosis | Concomitant STI | Genotype | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2016 | M/30 | Sexual (MSM) | Positive | 2014 | Syphilis | 3 | Primary |

| Drug use | ||||||||

| 2 | 2016 | M/41 | Drug use | Negative | – | No | 4 | Reinfection |

| 3 | 2017 | M/63 | IV drug use | Positive | 2004 | No | 3 | Reinfection |

| 4 | 2017 | F/45 | Drug use | Positive | 2009 | No | 1a | Reinfection |

| Borderline personality disorder | ||||||||

| 5 | 2018 | M/48 | Sexual (MSM) | Positive | 1998 | Syphilis | 1a | Primary |

| 6 | 2018 | M/43 | Sexual (MSM) | Positive | 2014 | Syphilis | 4 | Reinfection |

| Drug use | ||||||||

| 7 | 2018 | M/38 | Sexual (MSM) | Negative | – | No | 4 | Primary |

| 8 | 2018 | M/49 | Drug use | Positive | 1993 | No | 3 | Reinfection |

| 9 | 2018 | M/51 | IV drug use | Positive | 1989 | No | 4 | Reinfection |

| 10 | 2019 | M/38 | Sexual (MSM) | Positive | 2018 | Syphilitic chancre | 1a | Primary |

| 11 | 2019 | M/61 | Sexual (MSM) | Positive | 2013 | No | 1a | Primary |

| 12 | 2019 | M/52 | IV drug use | Positive | 1990 | No | 4 | Reinfection |

| 13 | 2019 | F/62 | Bipolar disorder | Negative | – | No | 1b | Primary |

| 14 | 2019 | F/66 | Healthcare | Negative | – | No | No data | Primary |

| 15 | 2020 | M/48 | Sexual (MSM) | Positive | 2012 | C. trachomatis Proctitis | 1 | Reinfection |

| 16 | 2020 | M/36 | Sexual (MSM) | Positive | 2009 | M. genitalium Urethritis | 1a | Primary |

| Syphilis | ||||||||

| 17 | 2020 | M/38 | Sexual (MSM) | Positive | 2009 | Syphilis | No data | Primary |

| 18 | 2020 | F/42 | Sexual | Positive | 2017 | No | 1a | Reinfection |

| Drug use | ||||||||

| 19 | 2020 | M/34 | Sexual (MSM) | Negative | – | No | 4 | Primary |

| 20 | 2020 | F/45 | Sexual (HCV partner) | Negative | – | No | 1a | Reinfection |

| 21 | 2020 | M/50 | Drug use | Positive | 1990 | No | 1a+4 | Reinfection |

| 22 | 2020 | M/47 | IV drug use | Negative | – | No | 1a | Reinfection |

IV: intravenous route; F: female; M: male; MSM: men who have sex with men; STI: sexually transmitted infection.

Clinical characteristics of patients diagnosed with acute hepatitis C virus infection.

| N | Year | Sex/age | HIV | Symptoms | ALT (U/l) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2016 | M/30 | Positive | Asymptomatic | 75 | Cured with treatment |

| 2 | 2016 | M/41 | Negative | Asymptomatic | 212 | Cured with treatment |

| 3 | 2017 | M/63 | Positive | Asymptomatic | 102 | Not treated. Deceased |

| 4 | 2017 | F/45 | Positive | Asymptomatic | 54 | Cured with treatment |

| 5 | 2018 | M/48 | Positive | Asymptomatic | 303 | Cured with treatment |

| 6 | 2018 | M/43 | Positive | Asymptomatic | 684 | Cured with treatment |

| 7 | 2018 | M/38 | Negative | Asthenia | 441 | Cured with treatment |

| 8 | 2018 | M/49 | Positive | Asymptomatic | 234 | Cured with treatment |

| 9 | 2018 | M/51 | Positive | Asthenia | 58 | Cured with treatment |

| 10 | 2019 | M/38 | Positive | Asymptomatic | 256 | Cured with treatment |

| 11 | 2019 | M/61 | Positive | Jaundice, choluria, abdominal pain, pruritus | 1055 | Cured with treatment |

| 12 | 2019 | M/52 | Positive | Asymptomatic | 44 | Cured with treatment |

| 13 | 2019 | F/62 | Negative | Jaundice, choluria, vomiting | 1872 | Cured with treatment |

| 14 | 2019 | F/66 | Negative | Choluria, acholia, abdominal pain | 1557 | Spontaneous cure |

| 15 | 2020 | M/48 | Positive | Abdominal pain, low-grade fever | 137 | Cured with treatment |

| 16 | 2020 | M/36 | Positive | Jaundice, choluria, pruritus, asthenia | 2905 | Spontaneous cure |

| 17 | 2020 | M/38 | Positive | Asymptomatic | 210 | Spontaneous cure |

| 18 | 2020 | F/42 | Positive | Asymptomatic | 116 | Not treated |

| 19 | 2020 | M/34 | Negative | Abdominal pain, asthenia, low-grade fever | 673 | Cured with treatment |

| 20 | 2020 | F/45 | Negative | Asthenia | 120 | Cured with treatment |

| 21 | 2020 | M/50 | Positive | Asymptomatic | 77 | Cured with treatment |

| 22 | 2020 | M/47 | Negative | Asymptomatic | 174 | Cured with treatment |

F: female; M: male.

In the era of the elimination of hepatitis C, the study of acute infection is fundamental, since it allows us to understand which population groups transmission is taking place in, in order to be able to design effective prevention strategies that will allow us to achieve the stated objectives. Since in most cases the infection is asymptomatic, it is difficult to carry out studies with a large number of patients; therefore, knowledge of acute infection and transmission patterns may be incomplete. In our district, an increase in the incidence of diagnosed cases has been observed in the last two years. This is an increase that has also been documented in recent years in other districts.3,13 This study looks at 22 cases of acute infection, of which more than half occurred in people who had risky sexual relationships, mainly men who have sex with men, and most of them had another documented concomitant sexual infection. A high percentage of patients were HIV-positive with a known diagnosis, that is, it is substantiated that these people maintain risky behaviours despite knowing their infection status, which is related to a relaxation in measures to prevent sexual transmission in this group due to the safety offered by antiretroviral treatments. We have observed a change in transmission patterns, compared to our previous study.12 More than 10 years ago, the cases that were diagnosed were mainly related to healthcare and drug use, and practically no cases of sexual transmission were diagnosed, nor cases in HIV-positive patients. The fact that many cases of acute HCV infection are diagnosed in HIV patients is directly related to a greater awareness to request the hepatitis C test in this group of patients, regardless of whether they have symptoms or not, following the recommendations of the HIV patient management guidelines.14 All this leads us to think that sexual transmission of the hepatitis C virus in the general population, and in particular in the population of men who have sex with men, could be much higher than what we find in the studies. This is associated with the practice of certain sexual habits, such as anal sex, where a higher prevalence of sexually transmitted infections has been found,15 and is linked to the increase in recent years of all sexually transmitted infections in Europe.

People with drug addiction have always been considered one of the main risk groups, in which micro-elimination strategies are concentrated. In this group, we observed that transmission continues to occur, although this must be much greater than that found, since these patients do not usually access health centres or, if they do, in most cases they do so late.

The third group where transmission could be more frequent than that found in our study is in people with severe mental illness, where a higher prevalence of HIV infection, hepatitis B and C has been observed.16 In these people, the risk is probably multifactorial, associated with increased drug use and risky sexual behaviour, and not with mental illness alone.16–19

Unlike in the previous period, acute hepatitis is becoming less common in the health environment. The fact that in our environment all patients have access to treatment and are practically all cured means that there are fewer and fewer sources of contagion in the healthcare environment. The decrease in cases in the health environment is a fact that has also been observed in other districts.3

Regarding the distribution of the genotypes that are being transmitted, a change was observed with respect to the previous period. Currently genotypes 1a and 4 are the most frequently transmitted, while in the previous study genotype 1b was the most frequent. This is probably linked to the emergence of genotype 4 in Europe in recent years,20,21 especially among men who have sex with men.

The fact that patients under follow-up within the health system who present with risk factors are the only ones who are systematically requested to be screened for HCV infection implies a bias in the data and is therefore a limitation of our study. Despite this, given that transmission of the hepatitis C virus continues to occur, the elimination goal could still be a while away from being achieved. This study confirms that sexual transmission is more common than what was thought a few years ago and that, due to the heterogeneity of the population that maintains risky sexual behaviours and the asymptomatic nature of the infection in a high percentage of cases, micro-elimination strategies may not be sufficient to reach the elimination goal. Probably, with population screening, early detection and treatment would be more effective, as it would prevent the spread of the infection and, therefore, the elimination goal might be achieved before the year 2030.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Pérez Jiménez RD, Granados Monzón R, Hernández Febles M, Pena López MJ. Infección aguda por el virus de la hepatitis C: ¿en qué personas se está produciendo la transmisión? Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;45:192–197.