Gastric cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer mortality in Chile. To optimize early detection and surveillance of gastric premalignant conditions, the Chilean Association of Digestive Endoscopy (ACHED), together with the Chilean Society of Gastroenterology, updated its 2014 clinical guideline. Using the AGREE II methodology, multidisciplinary working groups conducted systematic reviews in PubMed, Cochrane, and Scielo through December 2024. Recommendations were agreed upon via a Delphi panel (≥80% agreement) and graded according to GRADE, assessing evidence quality and recommendation strength. An expert panel of Chilean and international gastroenterology, endoscopy and pathology specialists reviewed the evidence and reached consensus to issue recommendations for opportunistic gastric cancer screening and surveillance using upper GI endoscopy in adults. These recommendations are feasible to implement in Chile and other Latin American countries with a high incidence of gastric cancer that have the necessary resources available. They complement any future efforts at population screening and aim to improve early detection and prognosis of gastric cancer in high-risk populations.

El cáncer gástrico es una de las principales causas de mortalidad oncológica en Chile. Con el fin de optimizar la detección temprana y la vigilancia de las condiciones premalignas gástricas, la Asociación Chilena de Endoscopía Digestiva (ACHED), en conjunto con la Sociedad Chilena de Gastroenterología, actualizó su guía clínica publicada en el año 2014. Mediante la metodología AGREE II, se conformaron grupos de trabajo multidisciplinarios que realizaron revisiones sistemáticas de la literatura en PubMed, Cochrane y Scielo publicadas hasta diciembre de 2024. Las recomendaciones fueron consensuadas por panel Delphi (≥ 80% de acuerdo) y calificadas según GRADE, evaluando la calidad de la evidencia y la fuerza de cada recomendación. Un panel de expertos chilenos e internacionales en gastroenterología, endoscopía y patología revisó la evidencia disponible y alcanzó consenso para emitir recomendaciones de tamizaje oportunista y vigilancia de cáncer gástrico durante la endoscopía digestiva alta en adultos. Estas recomendaciones son implementables en Chile y otros países con alta incidencia de cáncer gástrico de América Latina, que cuenten con los recursos disponibles, complementan cualquier esfuerzo futuro de cribado poblacional y buscan mejorar la detección temprana y el pronóstico del cáncer gástrico en poblaciones de alto riesgo.

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most common cancer and the fifth leading cause of death from cancer in the world.1 The incidence and mortality of GC vary according to geographical location. In Latin America, Chile, Costa Rica, Guatemala and Colombia have the highest mortality rates in the region.2 In Chile, GC has historically been the leading cause of cancer deaths in men and the third in women, with mortality rates of 25 and 12 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants, respectively.3

Chronic Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection causes chronic gastritis that can lead to the development of chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG), with or without intestinal metaplasia (IM), and dysplasia.4 These are considered gastric premalignant conditions (GPMC) with increased risk of adenocarcinoma, especially of the intestinal type.5–7 Endoscopic surveillance of GPMC may promote GC diagnosis in its early stages (secondary prevention), with better prognosis due to therapeutic options with curative potential.8–11

In 2014, the Chilean Association of Endoscopy (ACHED) and the Chilean Society of Gastroenterology (SChGE) recommended GC risk assessment for patients over 40 years of age undergoing an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). They established endoscopic surveillance according to histopathologic criteria.8 This guideline is an update of the above mentioned clinical recommendations and aims to: (1) provide specific recommendations to endoscopists to promote the detection of early GC through standardized definitions and essential components of high-quality EGD; (2) provide tools to stratify the GC risk in patients undergoing an endoscopy, particularly the risk of intestinal-type adenocarcinoma preceded by GPMC; and (3) establish recommendations and best practices for endoscopic surveillance in patients with GPMC. This guideline does not provide recommendations for population-based screening, as Chile lacks sufficient endoscopic resources to implement a universal screening program, making targeted surveillance of high-risk GPMC the most appropriate strategy. Also, does not address management of patients with hereditary syndromes associated with increased GC risk.

MethodsThis guideline was prepared following recommendations by the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE II) for drafting clinical practice guidelines.12 During the first quarter of 2024, the ACHED and SChGE convened a group of gastroenterologists, digestive surgeons, pathologists, and endoscopy nurses involved in the diagnosis and prevention of GC in order to update the 2014 ACHED guidelines for early diagnosis of GC and endoscopic surveillance of GPMC. In addition, international experts in GPMC and GC, with established experience in the development of clinical guidelines (L.M; H.B.G; D.C; F.E.; S.C.S.), and an expert gastrointestinal pathologist (M.B.P) participated.

A coordinating group for the clinical guideline and thematic working groups were established to carry out a systematic review of the literature based on the following questions: (1) What are the main risk factors for GPMC and GC? (2) What elements should a quality EGD have for the detection of early GC and GPMC? (3) How to stratify the risk of GC in patients undergoing EGD? (4) Who should be included in an endoscopic surveillance program? (5) What characteristics should an endoscopic surveillance program have for patients with risk factors for GC? (Published separately). Sub-questions were then put forward in each working group.

We conducted independent systematic reviews for each of the agreed-upon Patients-Intervention-Comparison-Outcome (PICO) questions (see below). The systematic reviews focused on new evidence available since the publication of the first version of this guideline in September 2014.8 We searched the electronic databases PubMed, Cochrane Library and Scielo until December 31, 2024. Human clinical studies in English or Spanish were selected, with prioritization of meta-analyses and randomized clinical trials, as these provide the strongest certainty of evidence according to GRADE.13 Based on the questions and the systematic review, each working group prepared key statements and recommendations, which were submitted to a consensus according to the Delphi methodology using a Likert scale categorized as follows: (1) Strongly agree; (2) Partially agree; (3) Neutral; (4) Partially disagree; (5) Strongly disagree. In case of disagreement, the recommendation was revised and voting repeated. Consensus was considered when ≥80% of votes were obtained at levels of complete or partial agreement (Likert scale 1 or 2). Recommendations with less than 80% agreement after discussion were excluded. All key statements and recommendations were graded based on the certainty (quality) of the evidence (A: High certainty; B: Moderate certainty; C: Low certainty; D: Very low certainty) and recommendations were also graded based on the strength of recommendation (1: Strong recommendation; 2: Weak/Conditional recommendation) according to the GRADE methodology (Supplementary Material).13 The coordinating group wrote the manuscript, and it was reviewed, edited for critical content and approved by all experts in the previously described phases including international experts. This guideline is expected to be updated within 5 years or sooner if there is a substantial change in the available evidence.

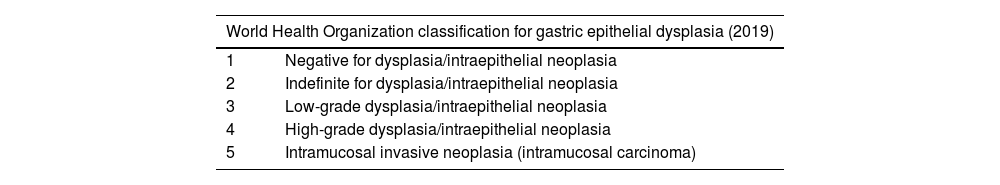

ResultsThe recommendations, agreement rate, level of evidence, and strength of recommendation are summarized in Table 1.

Summary of recommendations.

| Recommendations | Agreement (Delphi) | Grade of evidence – strength of recommendation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I. Definition of risk factors, premalignant conditions, and early gastric cancer | |||

| 1.1 | H. pylori infection causes chronic inflammation of the gastric mucosa and is the main risk factor for non-cardia GC. | 100% | Grade A – Strong recommendation |

| 1.2 | The main risk factors for GPMC and GC are H. pylori infection, first-degree family history of GC, male sex, age over 50 years, tobacco use, salt consumption, and belonging to indigenous ethnic groups (e.g., Mapuche). | 100% | Grade B – Strong recommendation |

| 1.3 | GPMC independently increase the risk of intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinoma, especially if they are histopathologically severe or anatomically extensive. | 100% | Grade B – Strong recommendation |

| 1.4 | The risk of GC in patients with autoimmune gastritis (AIG), without H. pylori infection, is lower compared with H. pylori–associated CAG | 98% | Grade C – Strong recommendation |

| 1.5 | Gastric epithelial dysplasia corresponds to neoplastic changes in the epithelial cells of the gastric mucosa without evidence of invasion into the lamina propria. It is also called intraepithelial neoplasia or non-invasive neoplasia, and it is classified into indefinite, LGD and HGD. | 100% | Grade C – Strong recommendation |

| 1.6 | Early GC is defined as cancer limited to the mucosa or submucosa, regardless of the state of the lymph nodes | 96% | Grade C – Conditional recommendation |

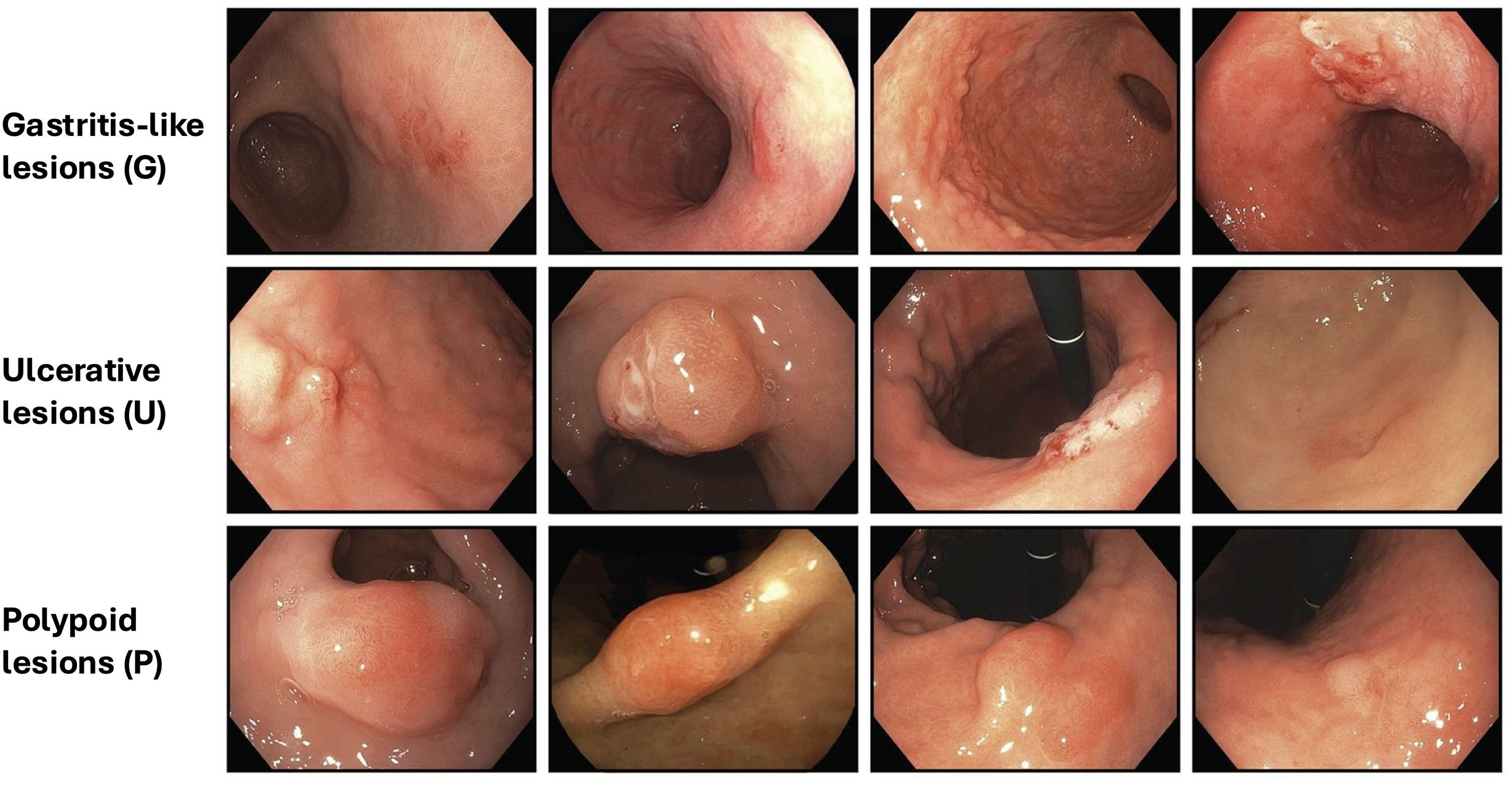

| 1.7 | Endoscopically, early gastric neoplasms appear as focal lesions and can be recognized as gastritis-like, ulcerated, or polypoid lesions. Endoscopic evaluation with image-enhanced endoscopy (IEE) can help define the size, depth, ulceration, and histopathological subtype to guide treatment. However, the diagnosis requires histopathological confirmation. | 98% | Grade C – Conditional recommendation |

| II. Quality in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy | |||

| 2.1 | ACHED recommends performing the EGD after at least 6-h fast on solids and maintain a clear liquid intake until 2h before the procedure. | 98% | Grade A – Strong recommendation |

| 2.2 | ACHED suggests that a small volume of cleansing solution (simethicone and N-acetylcysteine) be administered orally 20–30min before diagnostic upper endoscopy. To enable this practice, endoscopy units should ensure the availability of the cleansing solution as part of their standard preparation protocol. | 94% | Grade B – Conditional recommendation |

| 2.3 | ACHED recommends that an adequate visualization of the gastric mucosa must be achieved after washing with water, with or without anti-foaming or mucolytic agents, and aspirating the luminal contents as required. Validated scales are suggested to document gastric cleanness. | 98% | Grade B – Strong recommendation |

| 2.4 | ACHED recommends that a systematic and sequential gastric examination be performed, with both adequate insufflation and inspection time of the gastric mucosa. | 98% | Grade C – Strong recommendation |

| 2.5 | ACHED suggest using IEE techniques to optimize the characterization of early gastric neoplasms and GPMC, when resources and training are available. | 100% | Grade B – Strong recommendation |

| 2.6 | ACHED suggests training and application of validated endoscopic classifications to describe the state of the gastric mucosa, the extent of CAG and IM and focal lesions suggestive of an early gastric neoplasm. | 92% | Grade C – Strong recommendation |

| III. Diagnosis of gastric premalignant conditions and risk stratification | |||

| 3.1 | ACHED recommends ruling out a gastric neoplasm and categorize the future risk of GC in all adult patients undergoing diagnostic EGD (opportunistic screening) regardless of the indication or as part of a GC screening program. | 100% | Grade B – Strong recommendation |

| 3.2 | ACHED recommends testing for H. pylori infection in all adult patients undergoing diagnostic EGD if not previously tested. | 100% | Grade B – Strong recommendation |

| 3.3 | ACHED recommends complementing EGD with biopsies following the updated Sydney system (with targeted biopsies to areas of CAG/IM) during the first endoscopy in patients over 40 years of age, or regardless of age if there is a first-degree family history of GC or endoscopic findings suggestive of GPMC. | 96% | Grade A – Strong recommendation |

| 3.4 | ACHED suggests that gastric biopsies may be omitted when features of normal gastric mucosa are present, particularly regular arrangement of collecting venules (RAC) observed with HD-WLE or supra-angular pit pattern with a subepithelial capillary network displaying a ‘honeycomb’ appearance under IEE, if appropriate training is available. | 98% | Grade C – Strong recommendation |

| 3.5 | ACHED suggests that patients undergoing diagnostic EGD be classified into three risk categories for GC: (1) Low risk: Patients without present or past history of H. pylori infection, CAG, IM, gastric neoplasia or a first-degree relative with GC; (2) Reversible risk: patients with H. pylori infection, without CAG or IM; (3) Persistent risk: patients with CAG or IM, with or without H. pylori infection. | 100% | Grade C – Conditional recommendation |

| 3.6 | ACHED suggests that in patients with low risk (category 1), endoscopic surveillance is not needed. Patients at reversible risk (category 2) should be treated for H. pylori infection, and once eradication is confirmed, endoscopic surveillance may not be warranted. | 98% | Grade B – Conditional recommendation |

| 3.7 | ACHED recommends endoscopic surveillance for patients at persistent risk (category 3), specifically targeting a subgroup at the highest risk of progression to GC. | 98% | Grade B – Strong recommendation |

| 3.8 | ACHED recommends using the OLGA and OLGIM classifications to categorize the extent and intensity of CAG with or without IM and classify the subtype of IM (complete or incomplete) in gastric biopsies obtained according to the updated Sydney system. These features should be included in the histopathological report. | 92% | Grade B – Strong recommendation |

| IV. Endoscopic surveillance and management of gastric premalignant conditions and early gastric cancer | |||

| 4.1 | ACHED recommends enrolling at-risk patients in an endoscopic surveillance program to detect early gastric neoplasia, according to the suggested risk-based surveillance intervals below:1. Patients without GPMC with a first-degree family history of GC: every 5 years.2. Patients with OLGA or OLGIM II stage: every 4 years.3. Patients with OLGA or OLGIM III and IV stage every: 2 years.4. Patients with endoscopic evaluation suggesting high-risk GPMC (Kimura–Takemoto≥C3 or EGGIM>4): every 2 years.5. Patients with low- or high-grade dysplasia without an associated focal lesion: every 6–12 and 3–6 months, respectively.6. Patients with early gastric neoplasms (with LGD, HGD, or adenocarcinoma) treated with endoscopic resection or subtotal gastrectomy: at 3–6 months and then annually. | 94% | Grade B – Strong recommendation |

| 4.2 | ACHED recommends repeating the EGD by an expert endoscopist as soon as possible, using HD-WLE and IEE, when histopathological findings show LGD or HGD without an associated focal lesion. If still no lesion is identified, endoscopic surveillance should be performed every 6–12 and 3–6 months, respectively. | 98% | Grade C – Strong recommendation |

| .3 | ACHED suggests against endoscopic surveillance of early GC in patients without a significant risk of GC, as well as discontinuing surveillance for those who no longer derive benefit, according to the following criteria:1. Patients with endoscopically normal gastric mucosa (RAC with HD-WLE or normal mucosal surface pattern with IEE) and no other risk factors for GC as listed in statement 4.1.2. Patients without CAG or IM (stage OLGA or OLGIM 0) in the absence of persistent H. pylori infection or a first-degree relative with GC.3. Patients with mild CAG or IM, antrum-restricted complete-type IM and OLGA/OLGIM I in the absence of persistent H. pylori infection or a first-degree relative with GC.4. Patients with limited life expectancy either due to age or associated comorbid conditions. | 94% | Grade B – Conditional recommendation |

| 4.4 | ACHED suggests less strict endoscopic surveillance every 4 years when the etiology of CAG is autoimmune. It is recommended to consider additional risk factors, such as H. pylori infection or neuroendocrine neoplasms to shorten surveillance intervals. | 96% | Grade C – Conditional recommendation |

| 4.5 | ACHED recommends attempting an en bloc endoscopic resection for early gastric neoplasms harboring dysplasia or adenocarcinoma. The preferred technique is endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). However, non-ulcerated lesions, without a nodular component (I-s) or depressed lesions (II-c), smaller than 20mm may be resected using endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or hybrid-ESD. Evaluation and therapeutic decisions should be made by multidisciplinary teams with oncological experience. | 98% | Grade C – Strong recommendation |

| 4.6 | ACHED recommends H. pylori eradication treatment followed by post-treatment confirmatory testing in patients with active H. pylori infection and GPMC, dysplasia or GC. | 100% | Grade B – Strong recommendation |

| 4.7 | ACHED does not recommend routine use of acetylsalicylic acid, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, COX-2 inhibitors, statins, or metformin as chemoprophylaxis to reduce the risk of GC in patients with GPMC. | 98% | Grade B – Strong recommendation |

H. pylori produces chronic infection in the human stomach, leading to varying degrees of gastritis. Although H. pylori is estimated to still infect 40% of the world's population, this represents a marked decrease in its prevalence globally and particularly in Latin America, during the last decades.14 Based on extensive clinical and epidemiological evidence, H. pylori is considered the main causative agent of GC, especially non-cardia GC.15–17 The International Agency for Research on Cancer18 has recognized H. pylori as a type I carcinogen since 1994 and it is estimated that it accounts for 90% of non-cardia and 20% of cardia GCs globally.18–20 Among individuals chronically infected with H. pylori, the incidence of GC has been estimated at 0.37%, 0.5%, and 0.65% at 5, 10 and 20 years, respectively.21 Although there is a stronger relationship between H. pylori and non-cardia and intestinal-type GC, more evidence has emerged on the relationship with cardia GC, especially in Asian populations,16,22 and the diffuse type, with predominance of other genetic or environmental factors.23

The main risk factors for GPMC and GC are H. pylori infection, first-degree family history of GC, male sex, age over 50 years, tobacco use, salt consumption, and belonging to indigenous ethnic groups (e.g., Mapuche). [Agreement: 100%; Quality of evidence: B]H. pylori infection is the main risk factors for GPMC and, accordantly, gastric adenocarcinoma.15–17 Other relevant risk factors for GC are first-degree family history, male gender, age over 50 years, and ethnicity, with a higher risk in Latino, Asian, Black, and indigenous ethnic groups such as Mapuche.24–26 A meta-analysis that evaluated the main risk factors for GC in Latin America, based on 29 case-control studies, demonstrated that the main confirmed or probable risk factors were tobacco use, consumption of chili peppers, alcohol use, high consumption of processed meat, excessive salt intake, and carriage of IL1RN*2. In contrast, fruit and vegetable consumption was associated with lower risk.27 The role of Epstein–Barr virus infection in the region is yet to be determined.26 Other relevant risk factors for GC reported in Central America could be the use of wood-burning stoves and poor oral health.28

GPMC independently increase the risk of intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinoma, especially if they are histopathologically severe or anatomically extensive. [Agreement: 100%; Quality of evidence: B]CAG with and without IM and dysplasia are considered GPMC due to the independent increased risk of developing gastric adenocarcinoma.5,29 They correspond to multifocal changes in the gastric mucosa secondary to chronic inflammation, usually caused by H. pylori infection, and less commonly autoimmunity.30 CAG is defined by the loss of glandular structure, and IM by the replacement of the gastric epithelium by an intestinal epithelium, which can be classified as complete, incomplete and mixed subtypes.31 A recent meta-analysis which included 126 studies worldwide, estimated a global prevalence of CAG, IM, and dysplasia of 25%, 16%, and 2% respectively, which were more frequent in countries with medium or high GC incidence, compared to low-incidence countries, with no significant differences between symptomatic and asymptomatic populations.32 In Chile, CAG prevalence (measured by pepsinogen or biopsy) was 30% in people over 40 years of age in an area of high mortality from GC.33,34

Multiple cohorts and observational studies have demonstrated the increased risk of high-grade dysplasia (HGD) and adenocarcinoma in individuals with CAG and IM. This risk correlates with the histopathological severity of the atrophy or metaplasia (mild, moderate or severe) and its anatomical extent (restricted to the antrum vs. extended to the body).5,22,29 In a cohort of more than 90,000 patients with GPMC, annual incidence of GC for CAG, IM, indefinite/low-grade dysplasia (IND/LGD), and HGD was 0.1%, 0.25%, 0.6%, and 6%, respectively, within 5 years after diagnosis.29 In Japanese patients with severe CAG, an incidence of GC of 0.53–0.87% per year has been reported.35,36 In the presence of extensive IM, a 5-year GC rate close to 10% has been reported.37 In a Chilean population with IM with high-risk criteria, an annual incidence of GC of 3.3% has been reported.7 Based on these studies, a higher risk of GC has been described in CAG with IM compared to CAG without IM. On the other hand, epithelial dysplasia has a progression to GC ranging from 21% to 57% at a 24-month follow-up.38

The risk of GC in patients with autoimmune gastritis (AIG), without H. pylori infection, is lower compared with H. pylori-associated CAG. [Agreement: 98%; Quality of evidence: C]AIG is characterized by an immune-mediated loss of the parietal cells of the corpus and fundus. This phenomenon leads to hypochlorhydria and loss of intrinsic factor, which is associated with nutritional deficiencies such as iron and vitamin B12 deficiencies.39 The diagnosis is based on the histological findings (corpus-restricted or corpus-predominant atrophic changes) associated with the presence of autoantibodies directed against the beta subunit of the H+/K+ ATPase pump, denominated anti-parietal cell antibodies, and/or antibodies directed against the intrinsic factor.40,41 An increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma has been described in patients with AIG42–44 or pernicious anemia, a late-stage manifestation of AIG.45 A recent meta-analysis of 13 observational studies and national registries demonstrated an incidence rate of GC, low-grade dysplasia (LGD), and type 1 gastric neuroendocrine tumors (g-NETS) of 0.14%, 0.52%, and 0.83% per person-years, respectively.43 In a nested case-control study in a cohort of Finnish women, an independent association of GC, predominantly in the body, with serum anti-parietal cell antibodies was described.46 In contrast, an Italian cohort of patients with AIG, naïve to H. pylori infection, showed the absence of adenocarcinoma cases in a median follow-up of 7.5 years.47 Since the sample size and follow-up of the study were limited, the low risk of GC selected population, and the young patients enrolled, it is not possible to definitively rule out the association between AIG and adenocarcinoma. However, it supports previous evidence showing a lower risk of GC when the etiology of CAG is autoimmune, compared to H. pylori infection.

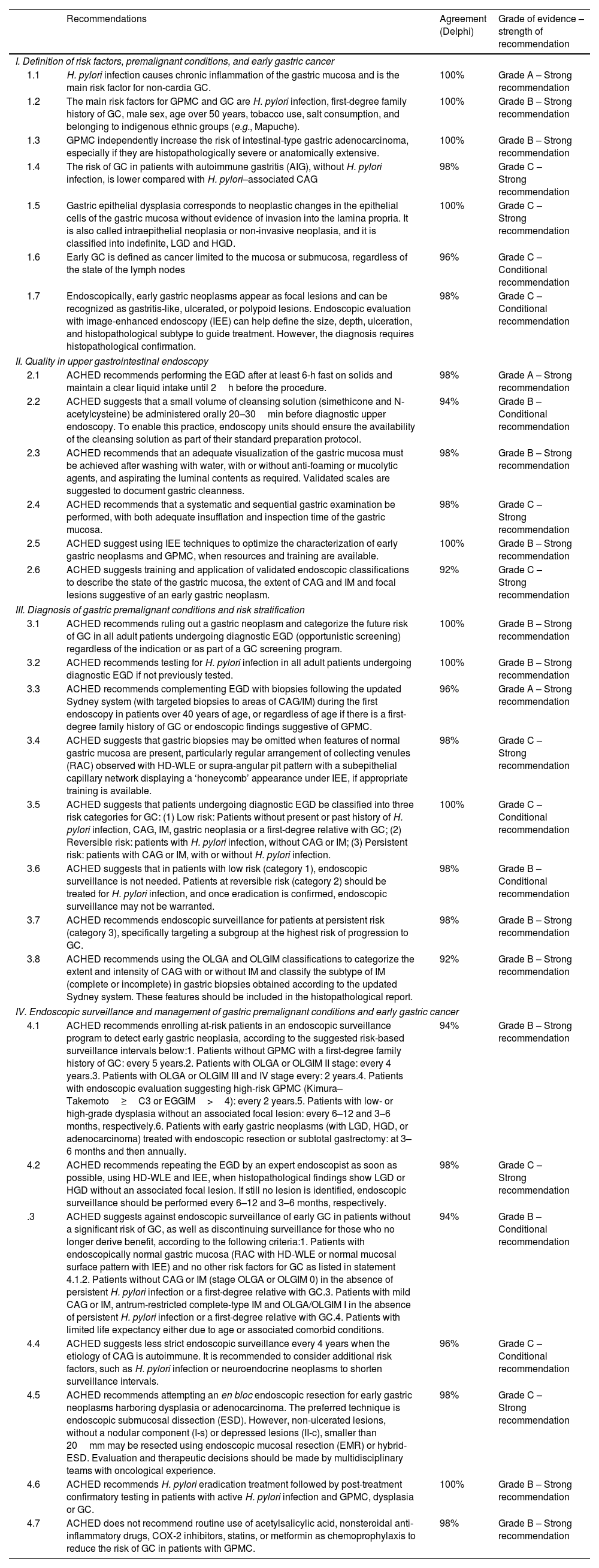

Gastric epithelial dysplasia corresponds to neoplastic changes in the epithelial cells of the gastric mucosa without evidence of invasion into the lamina propria. It is also called intraepithelial neoplasia or non-invasive neoplasia, and it is classified into indefinite, LGD and HGD. [Agreement: 100%; Quality of evidence: C]Gastric epithelial dysplasia is characterized by cytological changes, predominantly nuclear, and glandular architectural distortion. These changes can arise from both the native and metaplastic gastric mucosa. There is a variability in the terminology used to define dysplasia, mainly due to the differences between Western and Eastern pathologists. Multiple classifications of dysplasia have been proposed, the best known being the Padova and the Vienna classifications.48,49 The World Health Organization (WHO), in its most recent publication proposes a simplified system of 5 categories, which has been adopted by the present expert panel and described in Table 2.50 Furthermore, there are interobserver discrepancies among pathologists,51 especially when evaluating inflammatory and reactive changes. Therefore, the diagnosis of dysplasia should be reviewed by two pathologists or referred to an expert pathologist.

Categories of gastric epithelial dysplasia according to the World Health Organization classification 2019.

| World Health Organization classification for gastric epithelial dysplasia (2019) | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Negative for dysplasia/intraepithelial neoplasia |

| 2 | Indefinite for dysplasia/intraepithelial neoplasia |

| 3 | Low-grade dysplasia/intraepithelial neoplasia |

| 4 | High-grade dysplasia/intraepithelial neoplasia |

| 5 | Intramucosal invasive neoplasia (intramucosal carcinoma) |

Early GC is defined as any adenocarcinoma that invades the stroma, extending from the lamina propria through the muscularis mucosae and up to, but not beyond, the submucosal layer (pT1a and pT1b), without involvement of the muscularis propria.52 This definition is independent of loco-regional lymph node involvement as, even in early GC, there is a risk of lymphatic dissemination, especially in the presence of ulceration, deep invasion of the submucosa (pT1b>500μm), poorly differentiated histological subtype, or lymphovascular permeations.53–56 An early GC is considered amenable to endoscopic therapy when the risk of lymphatic dissemination is estimated to be lower than 1–3%, depending on the criteria used to define a curative resection.57

Endoscopically, early gastric neoplasms appear as focal lesions and can be recognized as gastritis-like, ulcerated, or polypoid lesions. Endoscopic evaluation with image-enhanced endoscopy (IEE) can help define the size, depth, ulceration, and histopathological subtype to guide treatment. However, the diagnosis requires histopathological confirmation. [Agreement: 98%; Quality of evidence: C]Endoscopically, an early gastric neoplasm (dysplasia or early adenocarcinoma among a focal lesion) can be detected according to findings on high-definition white-light endoscopy (HD-WLE), then characterized with IEE, including chromoendoscopy and magnification, and finally confirmed with a biopsy (1–2 samples). Early gastric neoplasms may be recognized as a gastritis-like, ulcerated, or polypoid lesion (Fig. 1).58,59 Attention should be paid to changes in coloration (pallor or erythema), topographic changes of the surface (depressed areas), spontaneous bleeding, contact friability, interruption of folds, opacity or loss of vascular transparency, among other signs as described in the MESDA-G algorithm (described below).60–62 As therapeutic decisions rely on a combination of endoscopic findings, histopathological characteristics, and patient-related variables, endoscopy reports should include, at minimum, a detailed evaluation of the lesion size, estimated depth of invasion, ulceration, and prediction of histopathological subtype.

Morphology of early gastric cancer based on the GUP system proposed by Yagi et al.58,59 Gastritis-like lesions (G): Superficial lesions resembling erosive or atrophic gastritis (Paris 0–IIa, IIb, IIc). Lesions are subtle, with slight surface or color changes. Key markers include localized changes in mucosal texture, color demarcation, and abrupt interruption of the background vascular pattern. Ulcerative lesions (U): Lesions with a depressed or ulcerated appearance (Paris 0–III) resembling peptic ulcers. Features include surface changes and shallow ulceration. Polypoid lesions (P): Elevated lesions resembling polyps (Paris 0–I). Lesions show focal protrusion above the surrounding mucosa, often with distinct color or surface abnormalities.

Retained gastric content and poor cleansing of the gastric mucosa compromising mucosal visualization are factors associated with missed gastric neoplasms during EGD.63,64 Although a 6h fast before an EGD ensures a stomach free of food content in most patients, lack of fluid intake favors the accumulation of mucus and foam, which hinders the examination and compromises visualization of the mucosa.65 Maintaining a regular intake of clear liquids up to 2h before the procedure reduces the presence of residues, facilitates the cleaning of the stomach, improve patient comfort and could promote the detection of gastric neoplasms, without increasing the risk of aspiration.66–69 In the case of patients using GPL1 agonists, users should withhold one dose before the procedure (equivalent to one week for weekly users or one day for daily users).70

ACHED suggests that a small volume of cleansing solution (simethicone and N-acetylcysteine) be administered orally 20–30min before diagnostic upper endoscopy. To enable this practice, endoscopy units should ensure the availability of the cleansing solution as part of their standard preparation protocol. [Agreement: 94%; Quality of evidence: B; Strength of recommendation: 2]Premedication with anti-foaming agents (simethicone) and mucolytics (N-acetylcysteine) has been evaluated in randomized clinical trials (RCT).71–73 Simethicone reduces the surface tension of the bubbles, facilitating their breakdown and N-acetylcysteine acts by breaking the disulfide bonds of the mucin, decreasing the viscosity of the mucus. A meta-analysis that included 13 RCTs with 11,086 patients showed a significant benefit in gastric mucosal visualization scores when implementing premedication with these agents, suggesting a greater effect when applied more than 20min before the procedure.74 While some studies have reported an increased detection of GPMC, no significant benefits in neoplasia detection have been demonstrated in controlled studies.71–73 In this context, it is recommended that the endoscopy units have a premedication solution available (e.g., water 100ml+simethicone 100–200mg+N-acetylcysteine 600mg) to be orally administered at least 20–30min before the endoscopy. There are clinical situations in which the use of cleansing solutions may be contraindicated or not feasible. For example, patients at high risk of aspiration, severe nausea, vomiting or GERD, or with contraindications to fluid intake may not benefit from this preparation and could even be harmed. In addition, the systematic implementation of this measure may face logistical and institutional barriers, such as the need for staff to administer the solution, potential delays in procedure scheduling, workflow adjustments, and possible increased costs. In settings where anesthesia is used, additional coordination may be required to ensure safe and timely administration.

ACHED recommends that an adequate visualization of the gastric mucosa must be achieved after washing with water, with or without anti-foaming or mucolytic agents, and aspirating the luminal contents as required. Validated scales are suggested to document gastric cleanness. [Agreement: 98%; Quality of evidence: B; Strength of recommendation: 1]Flushing through an accessory channel with water and simethicone or N-acetylcysteine solutions is a regular practice but has not been studied in clinical trials. The potential risk of biofilm development due to retention of simethicone droplets in the endoscope channels, despite high-level disinfection, has been raised. An American multi-society guideline recommends that if simethicone is required, it should be used in the lowest possible concentration (0.5% or less) and always through the working channel, avoiding its use through the water jet channel to minimize potential risks.75 In order to document and standardize the quality of endoscopy, the use of validated scales for assessing gastric cleanliness, such as the Toronto or Barcelona scale, is suggested.66,76

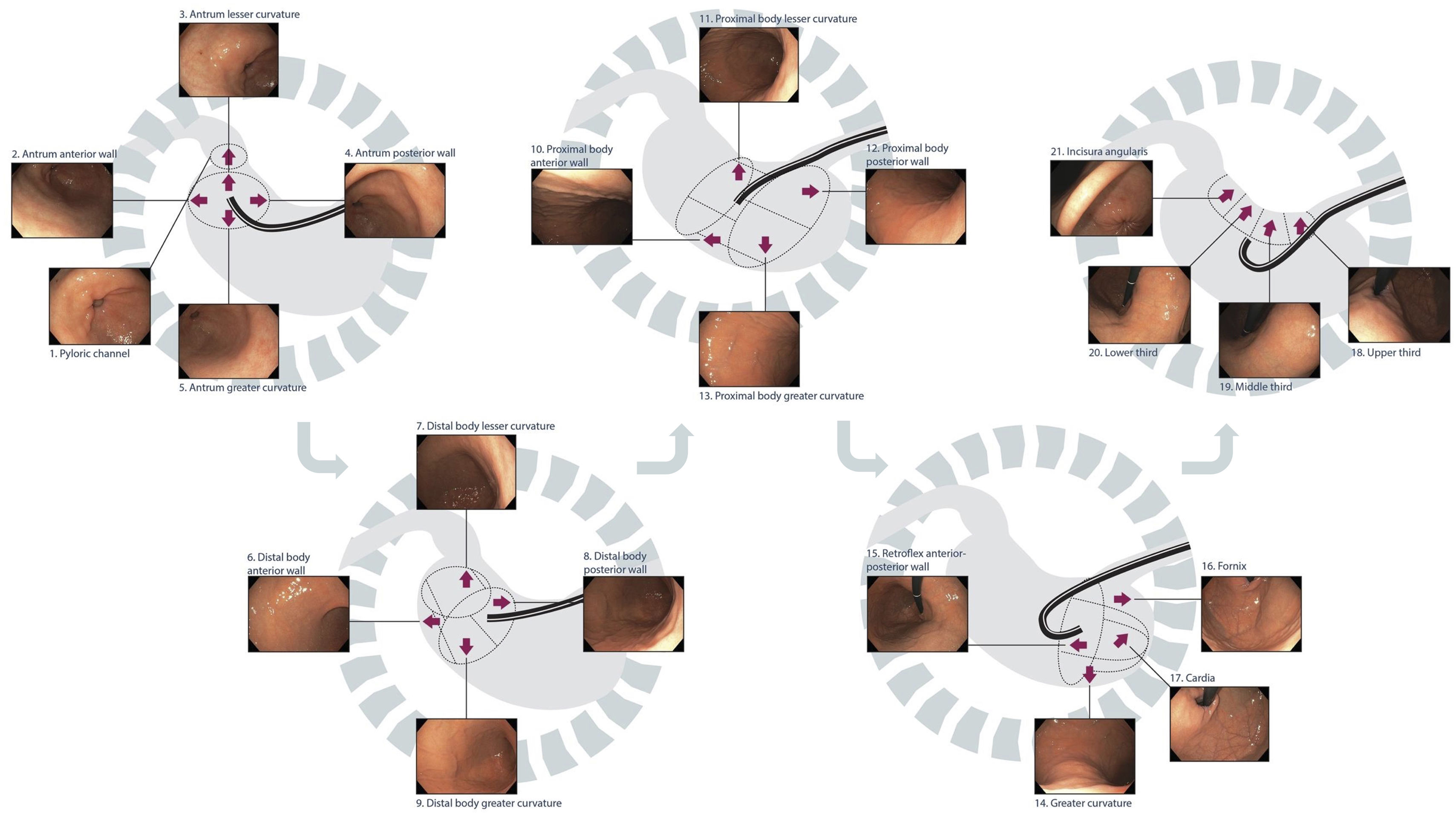

ACHED recommends that a systematic and sequential gastric examination be performed, with both adequate insufflation and inspection time of the gastric mucosa. [Agreement: 98%; Quality of evidence: C; Strength of recommendation: 1]The stomach's large surface with endoscopic blind spots necessitates a systematic evaluation of each anatomical region – pylorus, antrum, angle, body, fundus, and cardia – following an organized quadrant-based sequence. This is a key aspect of endoscopy quality, helping to address blind spots and avoid missed lesions. The photo documentation of these anatomical stations confirms a complete exam and the basis for future comparisons. Abnormal findings should be described according to the quadrant and anatomical region where they located (e.g. posterior wall of the upper body, minor curvature of the antrum) and appropriately photo documented. Different systems have been proposed for systematic and sequential examination of the stomach, such as the SSS system by Yao et al.60 or the alphanumeric system by Emura et al. (Fig. 2),77which not only includes the stomach, but also the hypopharynx, esophagus, and duodenum. As no studies have directly compared the diagnostic yields of these systems, the routine use of any of them is recommended.

Systematic and sequential gastric examination using high-definition white light endoscopy (HD-WLE).

Moreover, gastric examination time is proposed as a surrogate marker for the thoroughness of the examination. A longer gastric examination time is associated with a greater detection of GPMC and gastric neoplasms. An observational study in Singapore, which included 837 endoscopies performed by 16 endoscopists, compared 8 fast endoscopists (average endoscopy time: 5.5±2.1min) with 8 slow endoscopists (8.6±4.2min). The slow endoscopists had a threefold higher detection rate of dysplasia or cancer (OR 3.42; 95% CI: 1.25–10.38), suggesting that a duration greater than 7min may be the optimal time for an EGD.78 In an experience of 1206 consecutive endoscopies at a university center in Chile, a longer gastric examination time was independently associated with a greater detection of CAG and IM.79 An observational study of 55,786 endoscopies in Japan found the, neoplasia detection rate was 0.57% in fast endoscopists (mean endoscopy time 4.4min) and 0.94% in slow endoscopists (mean time 7.8min) (OR 1.90; CI 1.06–3.40), suggesting the need to spend at least 5–7min for each endoscopy.80 A real-world study reported a significant increase in neoplasm detection by applying an institutional policy of a minimum examination time of 3min, compared to their historical rate of neoplasm detection before this intervention (0.33% vs. 0.23%; adjusted OR 1.51; 95% CI 1.21–1.75).81 In addition to the endoscopist's speed, essential quality factors—such as proper sedation—help enable a systematic examination and sufficient inspection time.

ACHED suggest using IEE techniques to optimize the characterization of early gastric neoplasms and GPMC, when resources and training are available. [Agreement: 100%; Quality of evidence: B; Strength of recommendation: 1]High-definition endoscopy is superior to standard-definition endoscopy for detecting upper gastrointestinal neoplasia.82 In addition, adjunctive IEE technology, such as virtual chromoendoscopy, e.g. narrow band imaging (NBI; Olympus), blue light imaging (BLI; Fuji) or linked color imaging (LCI; Fuji), and magnification endoscopy, increase the sensitivity and specificity of GPMC and gastric neoplasms compared to WLE alone when proper training is available. A meta-analysis that included 8 prospective studies showed that, compared with HD-WLE, NBI detected IM more frequently (70% vs. 38%; RR 1.79; 95% CI 1.34–2.37), however, this difference was significant for newer endoscope series (Olympus GIF260), and no differences were observed in the detection of dysplasia.83 Another meta-analysis of 14 studies focused on the performance of magnified NBI (ME-NBI) to detect early gastric neoplasms, demonstrating a sensitivity and specificity of 86% (95%CI 83–89) and 96% (95%CI 95–97) for ME-NBI compared to 57% (95%CI 50–64) and 79% (95%CI 76–81) for HD-WLE.82 An RCT conducted in 19 hospitals in Japan demonstrated a higher diagnostic yield of gastric or esophageal neoplasms with the use of LCI compared to HD-WLE (8.0% vs. 4.8%; risk ratio 1.67; 95%CI 1.12–2.50), with lower frequency of missed neoplasia.85

Artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a promising tool to enhance endoscopy quality, detection rates, characterization of gastric neoplasia, and endoscopic risk stratification. However, the available tools still require further technological improvements and validation, particularly within Western clinical settings and among endoscopists with varying levels of expertise, before they can be recommended for routine clinical use. In a controlled clinical study conducted in 5 hospitals in China, a time-based AI system was evaluated to monitor blind spots based on deep learning of 26 gastric examination sites. The application of this system significantly reduced blind spots during endoscopy (5.38 vs. 9.82 blind spots; p<0.001) and correctly detected three early gastric neoplasms and two advanced neoplasms (100% sensitivity; 84% specificity).86 On the other hand, tools are being developed for automatic detection of gastric neoplasms, recording of gastric inspection time and photo documentation during endoscopy.87,88

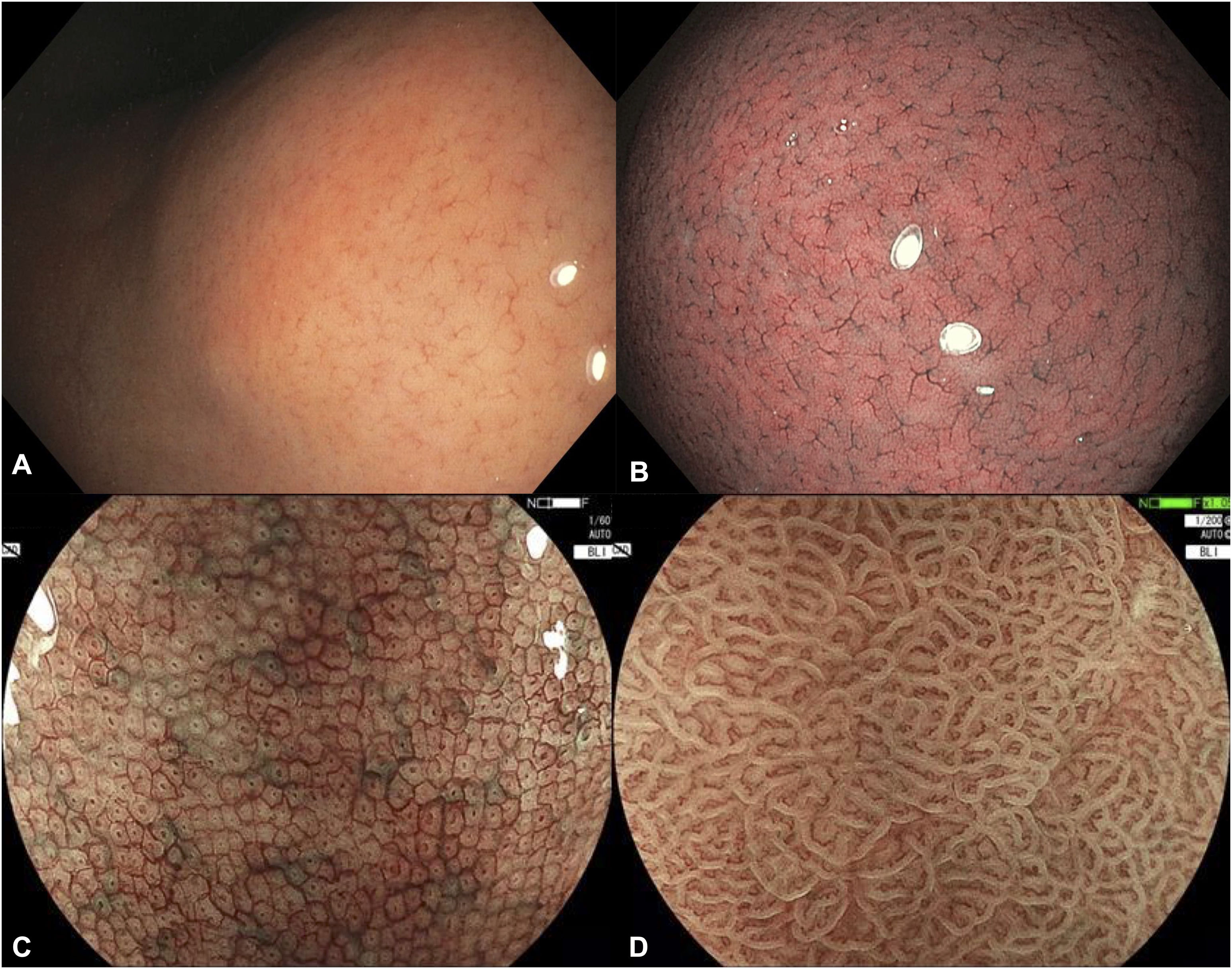

ACHED suggests training and application of validated endoscopic classifications to describe the state of the gastric mucosa, the extent of CAG and IM and focal lesions suggestive of an early gastric neoplasm. [Agreement: 92%; Quality of evidence: C; Strength of recommendation: 2]Recognition of normal gastric mucosa is the first and essential step in assessing mucosal status (Fig. 3), identifying H. pylori infection, and stratifying the risk of GPMC. It also enables the detection of neoplastic abnormalities and appropriate targeting of biopsies. A full description of normal features is beyond the scope of this guideline; however, the panel highlights the regular arrangement of collecting venules (RAC) (Fig. 3A) and the supra-angular pit pattern displaying a “honeycomb” subepithelial capillary network under IEE (Fig. 3B), as reliable markers of normality when appropriate training is provided.

Endoscopic findings of a normal gastric mucosa. (A) Regular arrangement of collecting venules (RAC) on high-definition white-light endoscopy; (B) RAC and normal corporal pit pattern on narrow band imaging (NBI); (C) Supra-angular pit pattern and subepithelial capillary network with a ‘honeycomb’ appearance on blue light imagine (BLI) and magnified endoscopy (ME); (D) Normal antral microsurface and microvascular pattern on BLI and ME. Images C and D were kindly provided by Dr. Robert Bechara.

The Kimura–Takemoto (K–T) classification has been proposed to stratify the antrum-to-corpus progression of H. pylori-related CAG based on identifying the atrophic border between the atrophic and preserved mucosa. Thus, the atrophic border is classified into 6 stages, three closed (C1–C3) and three open (O1–O3). The greater the degree of body extension of the atrophic border, the greater the risk of progression to GC, especially in open phenotypes. A cross-sectional study from Japan, which included 27,777 endoscopies, demonstrated a positive significant correlation between K-T classification and the GC detection rate (C0: 0.04%; C1:0%; C2: 0.25%; C3: 0.71%; O1: 1.32%; O2: 3.70%; O3: 5.33%), both differentiated and undifferentiated types.89 However, there are limited validation studies in Western and Latin American populations. A retrospective study of 708 patients with IM at two centers in the United States showed that the presence of an open atrophy pattern (K-T O1-3) was related to a higher risk of progression to dysplasia (HR 13.34; 95% CI 5.3–33.4) and advanced GC (HR 6.4; 95% CI 2.4–16.8) compared to closed-type or absence of atrophic features.90 A prospective study of 573 patients (mean follow-up of 6.2 years) with treated H. pylori, described a cumulative incidence of GC of 0.7%, 3.4%, and 16% at 10 years for groups C0-C2, C3-O1, and O2-O3, respectively (HR 9.3; 95%CI, 1.7–174).37 One of the advantages of this classification for Latin America is its simplicity, as it only requires HD-WLE, which is widely accessible. However, further prospective further validation is needed in Western countries.

The EGGIM (Endoscopic Grading of Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia) classification has been proposed to evaluate the extent of IM by virtual chromoendoscopy with a score of 0 (absent), 1 (≤30%) and 2 (>30%) in 5 segments of the stomach, including the lesser and greater curvatures of the antrum and body, as well as the angle.91 In a cross-sectional study an EGGIM score>4 demonstrated a sensitivity of 89% and specificity of 95% for identifying patients with high-risk IM,92 using the Operative Link on Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia Assessment (OLGIM) system as a gold standard.93 A recent meta-analysis evaluated 4 studies (2 with NBI, 1 with BLI, and 1 with LCI) and concluded that an EGGIM score>4 (5–10 points) had a sensitivity of 92% (95%CI 86–96%) and a specificity of 90% (95%CI 88–93%) for identifying patients with OLGIM III/IV histology. Interestingly, this meta-analysis evaluated 2 case-control studies where an EGGIM score>4 showed an OR 7.46 (95% CI 2.06–23.05) for concurrent diagnosis of prevalent GC.94 In this context, the EGGIM classification would have the potential to identify patients at risk of progressing to GC without the need for biopsies, which is attractive in resource-limited and resource-conscious regions, as in Latin America. However, proper training among endoscopist and prospective studies are needed to further validate this classification and define surveillance intervals before recommending a purely endoscopic risk assessment without biopsies.

When a focal lesion suspicious for a gastric neoplasm is found, morphological description by means of the Paris classification is suggested.95 To endoscopically determine the probability of neoplasia, the MESDA-G algorithm has been proposed, which includes the evaluation of a demarcation line (DL), micro surface area (MS) and microvasculature (MV).62 The first step is the identification of an DL, a clear margin between the lesion and the surrounding mucosa (normal or preneoplastic). If a DL is identified, MS and MV are evaluated, which may be regular, irregular or absent. If the lesion has a DL, with irregular or absent MS or MV, the endoscopic diagnosis of early gastric neoplasia is suggested and should be confirmed histologically with biopsies. It has been estimated that 97% of early gastric neoplasms meet the criteria of this algorithm, but further validation is required in the West, and it should be considered that they may become less evident after treatment of the H. pylori infection.96

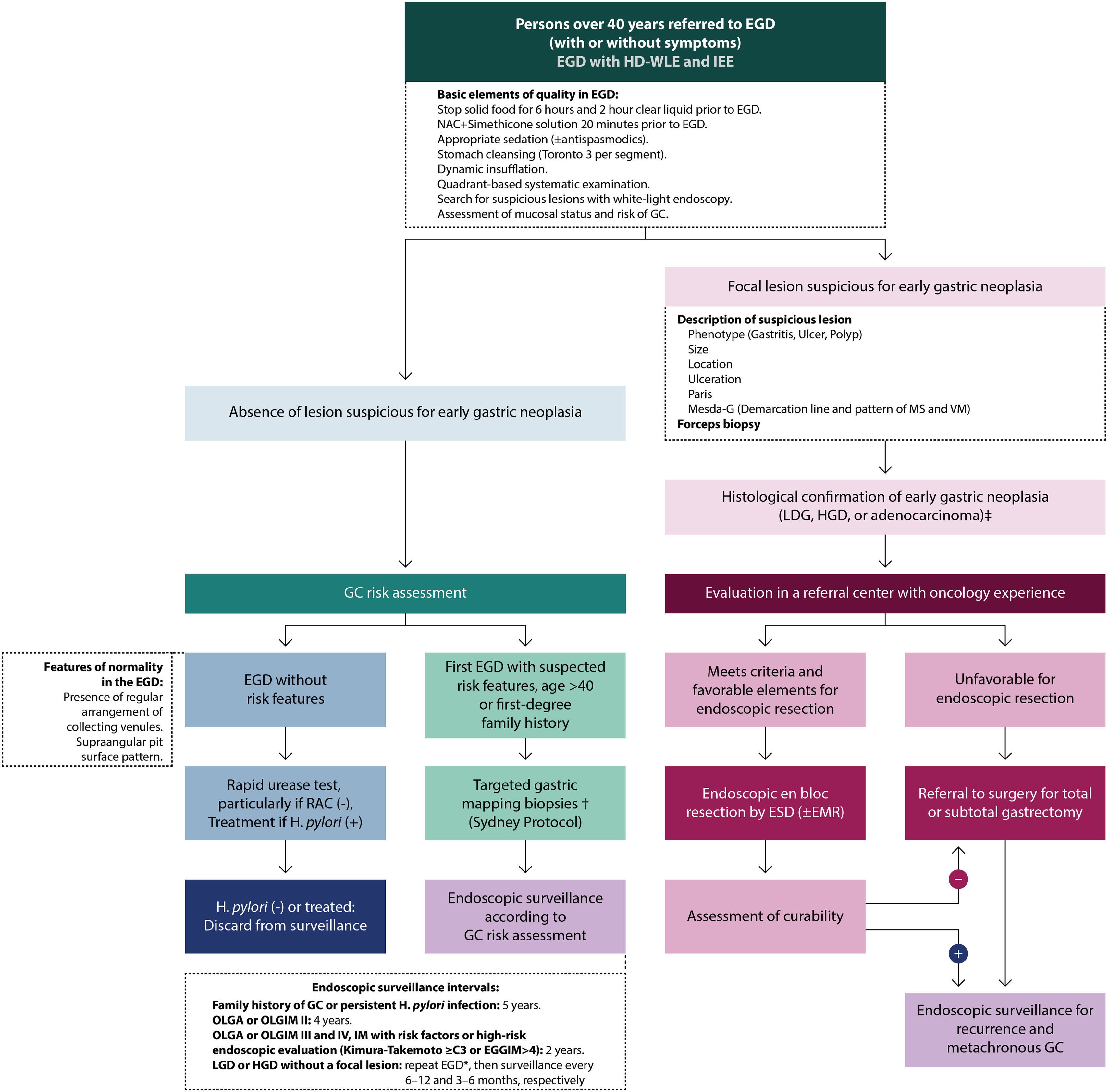

Diagnosis of gastric premalignant conditions and risk stratificationFig. 4 outlines the proposed management algorithm according to the ACHED guidelines for the detection and surveillance of early gastric cancer and premalignant gastric conditions.

ACHED flowchart guide for the detection of early gastric cancer and surveillance of premalignant gastric conditions. *Review LGD/HGD findings with expert GI pathologists. EGD should be repeated with HD-WLE and IEE as promptly with an experienced endoscopist to rule out an associated focal lesion. † Directing biopsies to areas of endoscopic suspicion of CAG or MI. ‡ In Chile, notification of Explicit Health Guarantees152,164. CG: gastric cancer; HGD: high-grade dysplasia; LGD: low-grade dysplasia; EDA: upper gastrointestinal endoscopy; EGGIM: endoscopic grading of gastric intestinal metaplasia; EMR: endoscopic mucosal resection; ESD: endoscopic submucosal dissection; H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; NAC: n-acetyl cysteine; MS: microsurface; MV: microvasculature; OLGA: Operative Link on Gastritis Assessment; OLGIM: Operative Link on Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia; RAC: regular collector venules.

Regardless of indication, every endoscopy is an opportunity to evaluate for prevalent neoplasia and to stratify any future risk of GC. This is especially relevant in high incidence GC populations, such as in Latin America, where opportunistic screening seems to be the most viable option for secondary GC prevention.97 The diagnosis of early GC is infrequent in Chile, accounting for approximately 10% of all GCs.3 This proportion contrast with reports from Japan and Korea, where more than 50% of GCs are detected at an early stage, significantly improving prognosis.98 These differences are likely attributable to limited access to endoscopy, prolonged waiting times, and a systematic prioritization of symptomatic patients over those undergoing screening procedures. Also, several systematic reviews have documented that missed gastric lesions during endoscopy is a frequent phenomenon, mostly relate to an inadequate endoscopic technique (e.g. inadequate mucosal cleaning, unexamined blind areas, too short gastric inspection time, among other factors), misclassification of lesions, inadequate sampling, or lack of follow-up.101 In a systematic review including 81,000 patients with upper digestive tract cancer, 11% of the patients had a “neoplasia-negative” EGD within a range of 6–36 months prior to the diagnosis of cancer.102 Interestingly, GC diagnosed 3 years after an EGD has not been linked to a worse prognosis. However, further studies are needed to assess the impact of missed neoplasms during endoscopy.63,102,104 Once an adequate evaluation has reasonably excluded a gastric neoplasm, the next step is to categorize the future risk of GC by assessing for H. pylori infection, GPMC and dysplasia.

ACHED recommends testing for H. pylori infection in all adult patients undergoing diagnostic EGD if not previously tested. [Agreement: 100%; Quality of evidence: B; Strength of recommendation: 1]H. pylori is the main risk factor for GC, and in Latin America, its prevalence has historically been high—around 70% according to studies from the 1990s and 2000s.104 However, a marked decline has been observed over time, with more recent reports in Chile indicating a prevalence of approximately 45% in 2010, decreasing to 29% in 2020, and a projected prevalence of 25% by 2025 based on data from 11,355 consecutive patients undergoing EGD.14 A recent expert consensus in Chile on strategies for GC prevention recommended initiating H. pylori screening and treatment for preventive purposes starting at the age of 35 years.97

There are invasive and non-invasive methods for the detection of H. pylori. During the EGD H. pylori infection can be diagnosed using a rapid urease test (RUT) or through protocolized gastric biopsies. If none of these diagnostic tools are available endoscopic findings—particularly presence of RAC—might be reliable to rule out H. pylori infection (see recommendation 3.6). In Chile, the vast majority of endoscopy units are equipped with RUT, which has acceptable sensitivity and provides results during the endoscopy, allowing for timely intervention. A recent meta-analysis reported sensitivities ranging from 80% to 100% and specificities between 97% and 99%.105 It is recommended to take a sample from the greater curvature proximal antrum and distal body to increase sensitivity (over 86%)106 and consider other diagnostic tests in the presence of bleeding, partial gastrectomy or recent use of proton pump inhibitors or bismuth due to their effect on sensitivity.107,108 For gastric biopsies, H&E with or without Giemsa staining is recommended for H. pylori detection, offering near 100% sensitivity if samples follow the Sydney protocol.109 However, in cases of advanced CAG or IM, histopathological recognition of H. pylori can be more difficult, therefore in these cases it is advisable to complement with non-invasive tests, such as an antigen stool test or urea breath test.110 Histopathological examination can be complemented with immunohistochemistry for H. pylori, which has a positive predictive value of 96% and a negative predictive value of 81%.111 Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a highly sensitive technique that also detects susceptibility to clarithromycin and fluoroquinolones. However, access is still limited in Latin America due to availability and costs. Due to its suboptimal sensitivity and specificity, as well as its inability to discriminate active vs. previous H. pylori infection, serological H. pylori testing is not routinely recommended.

ACHED recommends complementing EGD with biopsies following the updated Sydney system (with targeted biopsies to areas of CAG/IM) during the first endoscopy in patients over 40 years of age, or regardless of age if there is a first-degree family history of GC or endoscopic findings suggestive of GPMC. [Agreement: 96%; Quality of evidence: A; Strength of recommendation: 1]The sensitivity and specificity of the endoscopic diagnosis of GPMC are insufficient to provide an accurate risk assessment in all cases and depend on factors such as endoscopy quality, endoscopist training, and the availability of IEE techniques, which are not always accessible in Latin America. A study conducted in Chile showed a frequency of CAG according to age of 0% before 25 years, 5% between 25 and 44 years, 15% between 45 and 64 years, and 20% in those over 65 years of age.112 In this context, it is recommended to complement the risk assessment of GC at first endoscopy in patients over 40 years with targeted gastric mapping biopsies (updated Sydney system) to assess the presence or absence of H. pylori and the grading of GPMC, unless there are endoscopic criteria of normality (see below). Additionally, first-degree relatives of patients with GC have a 2–10-fold increased risk of GC, with a higher frequency of GPMC at younger ages, so they are included in this risk assessment.112–116

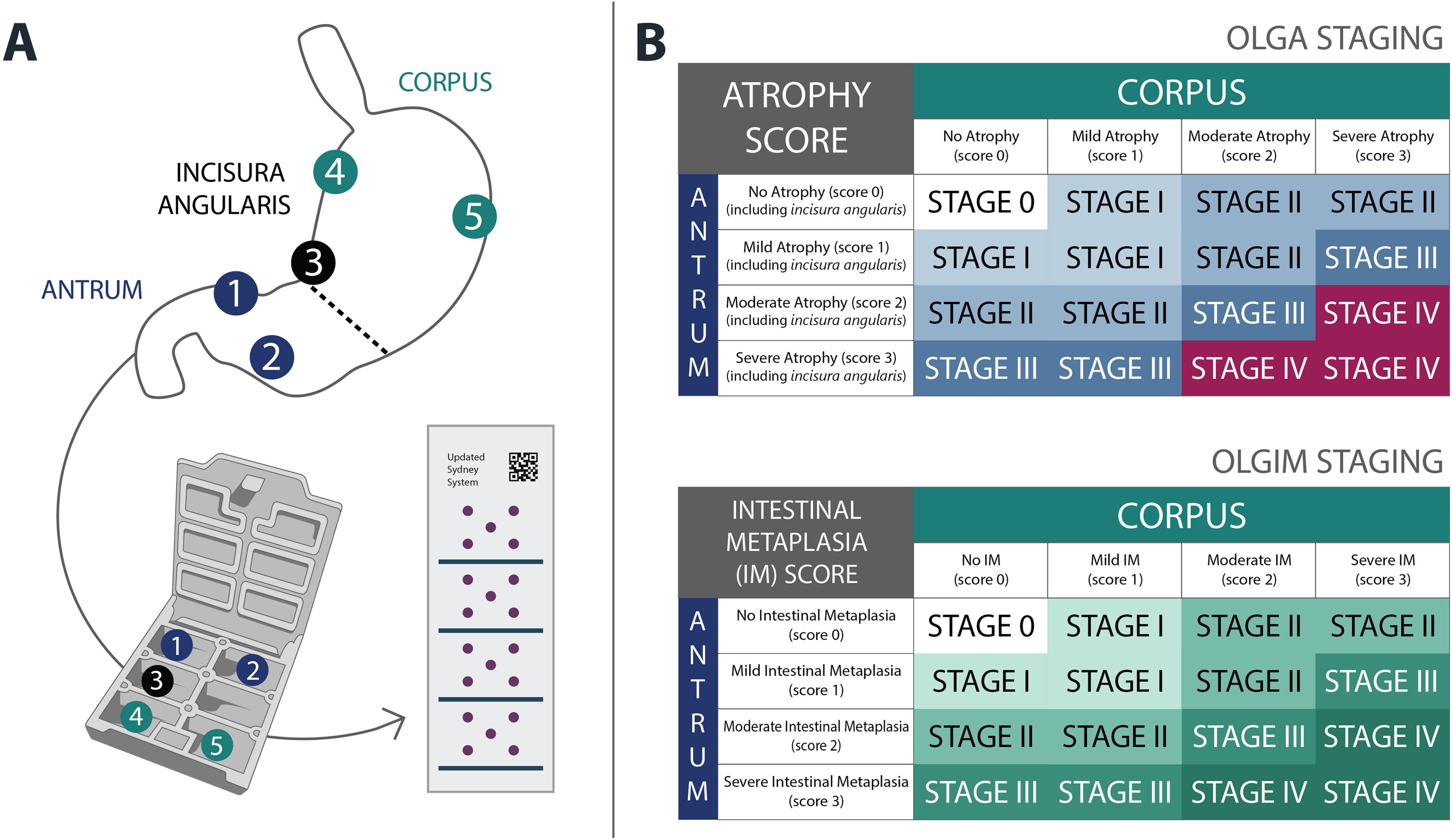

The updated Sydney system suggests taking at least 2 samples from the antrum, one from the incisura angularis, and 2 from the body, representing the lesser and greater curvatures (Fig. 5).117

Although antral and incisura angularis biopsies are analyzed together in the OLGA (Operative Link on Gastritis Assessment) and OLGIM systems, the panel considers that adding a separate sample from the incisura angularis is useful, given the natural history of CAG, which typically extends along the lesser curvature. Observational evidence suggests that including this site may improve not only the detection but also the accurate stratification of atrophy and intestinal metaplasia severity, without adding significant time or risk to the procedure.118,119 Also, it is suggested that in each anatomical region of Sydney protocol biopsies be directed to endoscopic findings suggestive of GPMC to optimize their performance given the multifocal nature of IM.120,121 Adherence to this protocol allows for greater detection of GPMC with more accurate risk stratification and determination of OLGA and OLGIM histopathological staging, as well as H pylori detection.79,122

ACHED suggests that gastric biopsies may be omitted when features of normal gastric mucosa are present, particularly regular arrangement of collecting venules (RAC) observed with HD-WLE or supra-angular pit pattern with a subepithelial capillary network displaying a ‘honeycomb’ appearance under IEE, if appropriate training is available. [Agreement: 98%; Quality of evidence: C; Strength of recommendation: 1]The endoscopic features of normal gastric mucosa are illustrated in Fig. 3. The presence of RAC (Fig. 3A) in the body mucosa on the evaluation with HD-WLE is a reliable marker of normal mucosa without H. pylori infection or atrophy.123,124 In the presence of advanced CAG, when H. pylori infection has been eradicated, collecting venules may be visible again, but with an irregular distribution. A meta-analysis of 15 studies involving 6621 patients evaluated for RAC, demonstrated a sensitivity of 98% (95% CI 96–99) and specificity of 75% (95% CI 54–88) for the absences of H.pylori.124 Another element of normality in endoscopy with magnification is the presence of a microsurface pit pattern and microvascular honeycomb pattern at the supra-angular distal body (Fig. 3B). Both features together constitute grade B0 in the classification proposed by Yagi et al. (B0: round pits with honeycomb subepithelial capillary network and collecting venules; B1: round pits with regular or mildly irregular honeycomb network, no collecting venules; B2: round or elongated pits with loss of honeycomb pattern, no collecting venules; B3: elongated pits with numerous grooves and disorganized vascular pattern, no collecting venules; A1: villous pattern with coiled capillary network, no collecting venules; A2: villous or absent mucosal pattern with irregular capillary network and disordered collecting venules).125 These findings with IEE reflect the indemnity of the fundic glands and absence of atrophy with 93% sensitivity and 100% specificity.126 Recognizing these features requires training and validation; however, it can significantly reduce the need for gastric biopsies by identifying low-risk patients who do not require further endoscopic surveillance.

ACHED suggests that patients undergoing diagnostic EGD be classified into three risk categories for GC: (1) Low risk: Patients without present or past history of H. pylori infection, CAG, IM, gastric neoplasia or a first-degree relative with GC; (2) Reversible risk: patients with H. pylori infection, without CAG or IM; (3) Persistent risk: patients with CAG or IM, with or without H. pylori infection. [Agreement: 100%; Quality of evidence: C; Strength of recommendation: 2]Apple.

ACHED suggests that in patients with low risk (category 1), endoscopic surveillance is not needed. Patients at reversible risk (category 2) should be treated for H. pylori infection, and once eradication is confirmed, endoscopic surveillance may not be warranted. [Agreement: 98%; Quality of evidence: B; Strength of recommendation: 2].Apple.

ACHED recommends endoscopic surveillance for patients at persistent risk (category 3), specifically targeting a subgroup at the highest risk of progression to GC. [Agreement: 98%; Quality of evidence: B; Strength of recommendation: 1]H. pylori is the main etiological factor for GC.15–18 A prospective study conducted in Japan thet included 1246 patients with H. pylori infection (demonstrated by histology, serology, or RUT) and 280 uninfected individuals, all undergoing periodic endoscopic follow-up (median of 7.8 years), detected 36 incident cases of GC (2.9%), which occurred exclusively in patients with H. pylori infection.127 Therefore, in the absence of H. pylori, CG risk is very low and there is no evidence to establish periodic endoscopic surveillance. First-degree relatives of patients with GC are excluded from the low-risk group, because a 2–10-fold increased risk of GC and a higher frequency of GPMC at younger ages have been described, although most of this risk is likely dependent on the presence of H. pylori.113–116

Treatment of H. pylori infection significantly reduces the risk of developing GC, especially in the absence of GPMC.128–131 A randomized controlled trial conducted in 1630 H. pylori-infected individuals from a GC high-risk region in China compared a 14-day triple therapy regimen with omeprazole, amoxicillin, and metronidazole with placebo. At 7.5-years follow-up, they observed 7 cases of GC in the treatment group and 11 in the placebo group (p=0.33). However, in the subgroup analysis of 988 patients without GPMC at study entry, none of the patients treated for H. pylori developed GC, whereas 6 cases were reported in the placebo group (p=0.02).132 Thus, treating H. pylori infection before the onset of GPMC reduces the subsequent risk of CG to a level comparable to uninfected individuals, making endoscopic surveillance unnecessary. Nevertheless, most longitudinal studies have shown that H. pylori treatment, while reducing risk, does not eliminate the possibility of developing GC in patients who have developed GPMC, especially if they are at high risk due to their severity, subtype, or body extension, in whom the benefit of endoscopic surveillance for the early detection of GC is concentrated.129,133 It is also critical to ensure that H. pylori eradication is confirmed following treatment, particularly considering the rising rates of treatment failure.

ACHED recommends using the OLGA and OLGIM classifications to categorize the extent and intensity of CAG with or without IM and classify the subtype of IM (complete or incomplete) in gastric biopsies obtained according to the updated Sydney system. These features should be included in the histopathological report. [Agreement: 100%; Quality of evidence: B; Strength of recommendation: 1]The OLGA system is a staging classification that assesses the extent and severity of CAG (with or without IM) and stratifies the risk of progression to GC into five stages, from 0 to IV, with stages III and IV representing the highest-risk categories (Fig. 5). It has been validated in cohorts from both high- and low-risk GC countries.5,7,134,135 However, low adherence to protocolized gastric biopsies collection and the interobserver variability among pathologists, have limited its routine application in clinical practice.93,124 In this context, the OLGIM system is an alternative system focused exclusively on IM extension (Fig. 5)93 and has also been validated in several cohorts.6,7,134–136 Its advantages are its lower interobserver variability and probably a better predictive capacity of GC.7

As previously mentioned, endoscopic systems have also been proposed for risk evaluation, such as the Kimura–Takemoto classification and EGGIM (see Recommendation 2.6).89–92 While OLGA and OLGIM benefit from extensive validation based on longitudinal cohorts conducted in Western countries,5,7,93,122,134,135 these histology-based systems may not be feasible in all contexts due to limited pathological resources or insufficient training. In such cases, endoscopic systems can be used alternatively for risk stratification. Additionally, when both endoscopic and histologic assessments are performed and discrepancies arise, we recommend using the system indicating the higher risk to guide subsequent surveillance decisions.

Endoscopic surveillance and management of gastric premalignant conditions and early gastric cancerACHED recommends enrolling at-risk patients in an endoscopic surveillance program to detect early gastric neoplasia, according to the suggested risk-based surveillance intervals below:- 1.

Patients without GPMC with a first-degree family history of GC: every 5 years.

- 2.

Patients with OLGA or OLGIM II stage: every 4 years.

- 3.

Patients with OLGA or OLGIM III and IV stage every: 2 years.

- 4.

Patients with endoscopic evaluation suggesting high-risk GPMC (Kimura–Takemoto≥C3 or EGGIM>4): every 2 years.

- 5.

Patients with low- or high-grade dysplasia without an associated focal lesion: every 6–12 and 3–6 months, respectively.

- 6.

Patients with early gastric neoplasms (with LGD, HGD, or adenocarcinoma) treated with endoscopic resection or subtotal gastrectomy: at 3–6 months and then annually.

[Agreement: 94%; Quality of evidence: B; Strength of recommendation: 1]

The available evidence, based on national and international cohorts, consistently demonstrates the higher risk of HGD and gastric adenocarcinoma in patients with GPMC with high-risk features. In a cohort of 1755 Italian patients, a progression rate of GC of 36.5 and 63.1 per 1000 person-years was described in stage OLGA III and IV patients, respectively, in contrast to a marginal risk in patients OLGA 0-I and very low in stage II. Another cohort of 2980 patients from Singapore reported an adjusted Hazard Ratio (a-HR) of 20.7 (95%CI 5.04–85.6) for the OLGIM III-IV patient group, using the OLGIM 0-I as reference group. Additionally, they described a significant risk for the OLGIM II group with an a-HR of 7.3 (95%CI 1.60–33.7). These findings were validated in the Chilean ECHOS cohort, in which the OLGA III-IV group showed a significant risk of HGD/adenocarcinoma, with progression rates of 18 cases per 1000 person-years, in contrast to a marginal risk in the OLGA 0-I groups. This cohort also assessed the OLGIM system, showing a risk of HGD/adenocarcinoma of 33 cases per 1000 person-years. A meta-analysis including 8 endoscopic surveillance cohorts and 12,526 patients suggested that, although the OLGA and OLGIM II groups have a lower risk of progression to HGD/adenocarcinoma compared to the OLGA and OLGIM III-IV groups, respectively, their risk is significantly higher than that of OLGA and OLGIM 0-I patients. Therefore, we also recommend endoscopic surveillance for OLGA or OLGIM II patients.137

Since the first version of this clinical guideline,8 the OLGA and OLGIM staging systems have been widely used in Chile. However, there are places with limited resources or where pathologists may not be trained in its use, or its application is not routine. Certain specific characteristics of IM, such as corporal extension or incomplete subtype, have been independently associated with an increased risk of HGD/adenocarcinoma, to be used as individual criteria of risk to establish endoscopic surveillance. On the other hand, when endoscopic-histopathological discrepancy arises, we recommend assuming the higher risk category. While the sensitivity and specificity of endoscopic findings with HD-WLE are insufficient for the accurate diagnosis of mild and moderate CAG and IM, especially in the antrum, corporal extension of the atrophic border or IM, as well as their involvement in the anterior and posterior walls of the gastric body (Kimura–Takemoto C3 and O1-3 or EGGIM>4), has been correlated with higher grades of OLGA and OLGIM and a significant risk of GC.37,89–92,138 Therefore, these extreme endoscopic features of CAG and GIM could be used to recommend endoscopic surveillance if no biopsies are available.

The persistence of H. pylori infection despite attempts at eradication is independently associated with an increased risk of progression in OLGA and OLGIM stages as well as an increased risk of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma.134 In a RCT of first-degree relatives of patients with GC, the persistence of H. pylori infection after treatment was one of the main risk factors for subsequent GC (HR 0.27; 95% CI, 0.10–0.70), with an increased risk of GC development starting from 2 years post-treatment.130 Although there is no strong evidence regarding the risk of GC in first-degree relatives without H. pylori infection or GPMC, the decision was to recommend late endoscopic surveillance (5 years) in this group of patients if no GPMC are present. In contrast, in patients without GPMC at the index endoscopy where H. pylori infection persists despite successive treatment attempts, it is suggested to maintain endoscopic surveillance every 2–3 years and to stratify risk according to the OLGA or OLGIM staging.

Gastric dysplasia can be found in gastric biopsies with and without a focal lesion and is associated with a higher risk of GC.139 A follow-up study of 118 patients with gastric dysplasia revealed that while 53% of LGD cases were not detected again during follow-up, this group still carried a 9% risk of progression to invasive adenocarcinoma (8/90).139 In the Chilean ECHOS cohort, 12 patients had LGD at the index endoscopy. During follow-up, 11 showed no dysplasia without endoscopic resection, while 1 patient progressed to HGD. Notably, among the 7 patients who progressed to adenocarcinoma, LGD was detected in at least one biopsy during follow-up in 3 cases.7 Therefore in the case of low- or high-grade dysplasia, without an associated resectable lesion, we recommended to repeat EGD with HD WLE with IEE as soon as possible with an experienced endoscopist. If still no lesion is identified, then maintain endoscopic surveillance every 6–12 months and 3–6 months, respectively.

The risk of metachronous GC after endoscopic or surgical removal of gastric neoplasms has been widely documented.140,141 A meta-analysis of 52 observational studies, including 28,014 patients treated with endoscopic resection and 4050 with subtotal gastrectomy, found a 5-year risk of metachronous gastric cancer of 9.5% and 0.7%, respectively.138 Also, metachronous GC can occur even past 10 years. Accordingly, we recommended a long-term close endoscopic surveillance following GC treatment until it is no longer medically appropriate or aligns with the patient's preference.

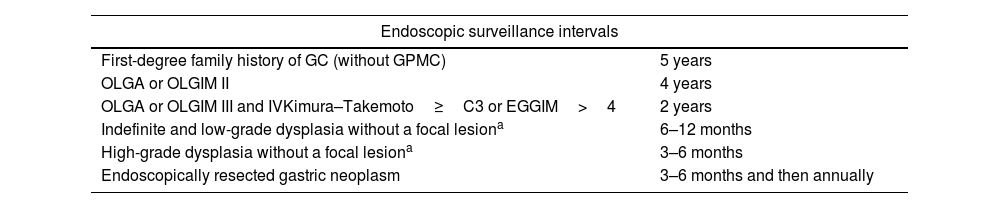

Regarding endoscopic surveillance intervals (Table 3), no RCTs have evaluated the effectiveness of different intervals for patients with GPMC. Therefore, intervals were defined based on observational evidence describing the natural history of GPMC, such as the absolute risk and median time to progression to HGD/adenocarcinoma, or studies assessing risk factors for interval GC or deep invasion at the time of diagnosis. The median time to HGD or adenocarcinoma for patients with OLGA III-IV was 24 months (range 23–49) in the cohort by Rugge et al. and 22.7 months (range 12.7–44.8) for OLGIM III–IV in the cohort by Lee et al.5,6 In this study, a median time to HGD/adenocarcinoma of 40.7 months (range 28.5–73.3) was described in OLGIM II patients. In the Chilean ECHOS cohort, the median time of progression of patients OLGA III-IV was 33 months (IQR 18–38).7 Recently, a multicenter observational study from Japan reported that a surveillance interval greater than 1.5 years is one of the main risk factors related to submucosal invasion of adenocarcinoma at the time of diagnosis in the follow-up of high-risk patients.143 In an RCT evaluating H. pylori treatment in relatives of GC patients, follow-up was conducted at 2-year intervals. This approach ensured that all detected GCs were identified at stage I or II, allowing for curative treatment.130 In this context, we suggested a 2-year surveillance interval for high-risk GPMC (OLGA or OLGIM III-IV) and a 4-year interval for intermediate-risk patients (OLGA or OLGIM II). Some patients may lack OLGA or OLGIM staging; in such cases, other endoscopic or histopathological features suggesting high-risk GPMC—such as corpus extension of IM or incomplete subtype—may be used to establish a 2-year surveillance interval. However, it is recommended to attempt risk stratification using OLGA or OLGIM whenever possible.

Proposed endoscopic surveillance intervals according to endoscopic and histopathological findings.

| Endoscopic surveillance intervals | |

|---|---|

| First-degree family history of GC (without GPMC) | 5 years |

| OLGA or OLGIM II | 4 years |

| OLGA or OLGIM III and IVKimura–Takemoto≥C3 or EGGIM>4 | 2 years |

| Indefinite and low-grade dysplasia without a focal lesiona | 6–12 months |

| High-grade dysplasia without a focal lesiona | 3–6 months |

| Endoscopically resected gastric neoplasm | 3–6 months and then annually |

Review biopsy by an expert gastrointestinal pathologist. Repeat endoscopy by an experienced endoscopist with high-definition and image-enhanced endoscopy. GC: Gastric cancer; GPMC: Gastric premalignant conditions; OLGA: Operative Link on Gastritis Assessment; OLGIM: Operative Link on Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia Assessment; EGGIM: Endoscopic grading of gastric intestinal metaplasia.

The detection of gastric neoplasms can be significantly affected by missing lesions during endoscopy, especially if quality standards are unmet as mentioned above.102,103 If LGD or HGD is identified, a review by a second pathologist or referral to an expert gastrointestinal pathologist is recommended. Upon confirmation of dysplasia, EGD should be performed promptly by an endoscopist with expertise in the diagnosis and endoscopic resection of early GC, utilizing HD-WLE and IEE to exclude the presence of early gastric neoplasia. A Dutch national registry reported an annual incidence of GC of 0.6% in mild-moderate dysplasia (LGD) and 6% in severe dysplasia (HGD).26 In a follow-up study of 118 consecutive patients with LGD and HGD, the progression rates to invasive adenocarcinoma were 9% (8/90) and 69% (11/16), with median follow-up periods of 48 months (range 21–85) and 30 months (range 13–72), respectively.139 Therefore, if no focal lesion is detected, endoscopic surveillance is recommended every 6–12 months for IND/LGD and every 3–6 months for HGD, particularly if dysplasia persists on histopathological assessment.

ACHED suggests against endoscopic surveillance of early GC in patients without a significant risk of GC, as well as discontinuing surveillance for those who no longer derive benefit, according to the following criteria:- 1.

Patients with endoscopically normal gastric mucosa (RAC with HD-WLE or normal mucosal surface pattern with IEE) and no other risk factors for GC as listed in statement 4.1.

- 2.

Patients without CAG or IM (stage OLGA or OLGIM 0) in the absence of persistent H. pylori infection or a first-degree relative with GC.

- 3.

Patients with mild CAG or IM, antrum-restricted complete-type IM and OLGA/OLGIM I in the absence of persistent H. pylori infection or a first-degree relative with GC.

- 4.

Patients with limited life expectancy either due to age or associated comorbid conditions.

[Agreement: 94%; Quality of evidence: B; Strength of recommendation: 2]

In the absence of risk factors such as CAG, IM, or persistent H. pylori infection, there is no evidence to support endoscopic surveillance. The presence of RAC or normal mucosal surface pattern has high specificity for diagnosing normal corporal mucosa and absence of H. pylori, with a very low future risk of CG.123,124,126 The low risk of GC in OLGA/OLGIM I patients has been documented in several cohorts from low- and high-risk areas, with exceptionally low rates of progression to HGD or adenocarcinoma.5,136,137 In this group, it is recommended to test and treat H. pylori infection, promoting healthy lifestyles, and modify risk factors such as smoking cessation, alcohol, reduced salt intake, processed meats, smoked or pickled foods, and maintaining good oral health.27

In a single-center Japanese study following 71 cases of early gastric cancer for 6–137 months, it was estimated that only 63% of early gastric neoplasms progress to more advanced or invasive stages, while the remaining lesions remain early, suggesting that their natural history is slow in most cases.144 In this context, endoscopic surveillance is not recommended for individuals with advanced comorbidities, limited life expectancy, or cases where the risks associated with sedation, endoscopy, or potential treatments for gastric neoplasms outweigh the benefits and may negatively affect quality of life. However, since the incidence of GC increases with age and the population is progressively aging, it is suggested not to limit surveillance to a specific age but rather base it on the patient's functionality, life expectancy, and preferences.

ACHED suggests less strict endoscopic surveillance every 4 years when the etiology of CAG is autoimmune. It is recommended to consider additional risk factors, such as H. pylori infection or neuroendocrine neoplasms to shorten surveillance intervals. [Agreement: 96%; Quality of evidence: C;Strength of recommendation: 2]AIG carries a lower risk of developing adenocarcinoma compared to H. pylori-associated CAG. Multiple observational and retrospective studies have linked AIG to GC, particularly in elderly patients.42,46 A recent follow-up study of 211 patients with AIG who had no history of H. pylori infection (serologically confirmed) reported a very low risk of adenocarcinoma, with no cases detected over a median follow-up of 7.5 years.47 Although this study suggests the safety of longer surveillance interval in patients with AIG without H. pylori, the small sample size and lack of a control group do not exclude the potential association between AIG and adenocarcinoma. A retrospective study involving 8 centers in Italy and 1598 patients with AIG, with a median follow-up of 89 months, described an adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine neoplasm rate of 1.2 (95%CI 0.7–2.0) and 12.2 (95%CI 10.3–14.2) per 1000 person-years, respectively, confirming the lower risk in patients with AIG.44 Although this study did not demonstrate significant differences in the risk of adenocarcinoma or neuroendocrine neoplasms based on H. pylori infection status, we recommend that when atrophic gastritis results from a combined etiology (autoimmune plus H. pylori), surveillance intervals should follow those recommended for H. pylori-associated CAG, considering the degree of CAG and IM. Although not yet fully investigated, other risk factors may be considered to justify a shorter follow-up in patients with AIG, such as a family history of GC, severity of CAG/GIM in the corpus, pernicious anemia, smoking, or advanced age. Additionally, it is suggested that surveillance intervals should be shortened in individuals with endoscopically resected neuroendocrine neoplasms based on their number, size, and histopathological grade.

ACHED recommends attempting an en bloc endoscopic resection for early gastric neoplasms harboring dysplasia or adenocarcinoma. The preferred technique is endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). However, non-ulcerated lesions, without a nodular component (I-s) or depressed lesions (II-c), smaller than 20mm may be resected using endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or hybrid-ESD. Evaluation and therapeutic decisions should be made by multidisciplinary teams with oncological experience. [Agreement: 98%; Quality of evidence: C; Strength of recommendation: 1]Endoscopic resection has become the treatment of choice for managing early gastric neoplasms when the lesions have a very low risk of lymphatic spread and conditions are favorable for en bloc resection.55,145–148 Although the specific management of early gastric neoplasms is beyond the scope of this guideline, it is recommended that, upon the finding of an early gastric neoplasm, with histopathological confirmation of dysplasia or adenocarcinoma, the best therapeutic approach should be discussed at a referral center with oncological expertise.

Multiple published experiences from both Eastern and Western countries have demonstrated the effectiveness and safety of ESD for resecting early gastric neoplasms.145,148–152 A meta-analysis of ESD in Western countries, which included 1210 lesions and 6 studies from Latin America, showed en bloc resection rates of 96% and R0 resection rates of 84%, with a complication rate of 9.5%, comparable to those obtained in Asian centers.152 A study on long-term outcomes of ESD in a high-volume center in Chile performed by experienced endoscopists reported an en bloc resection rate of 98%, 93% of resections were R0 and 83% met curative standards according to expanded criteria, suggesting that ESD is feasible and effective in Latin America.149

ESD is the preferred technique due to its higher en bloc resection capability compared to EMR, especially in lesions over 20mm,153,154 its ability to define lateral margins, dissect a deeper submucosal plane, and enable appropriate histopathological assessment of deep margins. However, ESD demands greater expertise, longer procedure time, and higher costs that are limited in Latin America. In this context, very low-risk lesions smaller than 20mm, without risk features, may be treated with EMR or hybrid ESD to reduce costs and procedural time, achieving similar oncological outcomes.155

In the context of an early gastric neoplasm, the biopsy may not represent the highest histopathological grade of the lesion. A meta-analysis reported that 25% of lesions initially classified as LGD were found to have HGD or adenocarcinoma upon evaluation of the complete resected specimen, especially in lesions larger than 20mm, with depressed areas (0-IIc) or nodular areas (0-Is) on their surface.156 Another experience in Chile including 134 gastric epithelial lesions showed that 38% of lesions with LGD were diagnosed as HGD or adenocarcinoma after en bloc resection by ESD.157 Therefore, en bloc resection is suggested regardless of the initial histopathological evaluation.

Following any endoscopic resection of an early gastric neoplasm, the resected specimen should be assessed to determine curability based on size, horizontal and vertical margins, degree of differentiation, depth of invasion, and lymphovascular invasion.57

ACHED recommends H. pylori eradication treatment followed by post-treatment confirmatory testing in patients with active H. pylori infection and GPMC, dysplasia or GC. [Agreement: 100%; Quality of evidence: B; Strength of recommendation: 1]The benefit of treatment of H. pylori infection on the prevention of non-cardia GC has been well documented when treatment occurs before the onset of GPMC,132 and more recently, in the prevention of metachronous GC.131 A RCT demonstrated that treatment of H. pylori compared to placebo reduces the risk of metachronous GC by 50% after endoscopic resection of gastric neoplasia, suggesting the benefit of H. pylori treatment even in advanced stages of premalignancy.131 Similarly, a significant reduction in the incidence of GC of 20% with H. pylori treatment has been shown in a cohort of 69,722 patients with endoscopically resected gastric dysplasia.158