Artificial intelligence (AI) allows the optimization of diagnostic processes for hepatitis C virus (HCV) patients. Our objective was to evaluate the clinical, economic, and management benefits of an AI-based clinical decision support system (Intelligen-C strategy).

MethodsThe Intelligen-C strategy consisted of (1) a retrospective phase (Dec 2013–Sep 2021), in which medical records were reviewed to search for anti-HCV-positive and/or HCV-RNA+ patients lost in the system, and (2) a prospective phase (Feb 2022–Jan 2023), in which automated screening (40–70 years) and routine testing for risk factors were performed in patients who were admitted to the emergency department or were hospitalized. With the use of automated screening, the system identified patients without an HCV diagnosis among those requiring blood tests and requested HCV serology; if the results were positive, reflex testing for HCV-RNA was performed. If a patient was HCV-RNA+, an alert was generated and sent to the hepatology department. In addition, the prospective phase was compared with the previous period to evaluate its effectiveness and efficiency.

ResultsIn the retrospective phase, the Intelligen-C strategy allowed the identification of 272 anti-HCV- or HCV-RNA+ patients who were lost to follow-up, of whom 11 were treated; in the prospective phase, after 7312 serologies were performed, 28 HCV-RNA+ patients were identified, 14 attended the appointment, and 9 were treated. In the prospective phase vs. the previous period, increased serology (7312 vs. 909), HCV-RNA+ detection (28 vs. 3), and treated patients (9 vs. 1) generated savings to the health system related to medical visits. In addition, Intelligen-C was cost-effective.

ConclusionsThe implementation of the Intelligen-C strategy allowed the identification of patients with undiagnosed infection, facilitated their diagnosis, reduced healthcare processes and associated hospital costs, and proved to be efficient.

La Inteligencia Artificial (IA) permite optimizar los procesos con pacientes con virus de la hepatitis C (VHC). Nuestro objetivo fue evaluar los beneficios clínicos, económicos y de gestión de un sistema de ayuda a la decisión clínica basado en IA (estrategia Intelligen-C) para el cribado automatizado del VHC.

MétodosLa estrategia Intelligen-C consistió en: 1) fase retrospectiva (Dic-2013 a Sep-2021): revisión previa a automatización de historias clínicas para buscar pacientes anti-VHC+/ARN-VHC+ perdidos en el sistema, y 2) fase prospectiva (Feb-2022 a Ene-2023): cribado automatizado (40-70 años) más las pruebas realizadas de rutina por factores de riesgo. En el cribado automatizado el sistema identificó pacientes sin diagnóstico VHC que acudían a urgencias o eran hospitalizados y precisaban analítica, solicitaba una serología VHC y, ante resultados positivos, solicitaba ARN-VHC. Si resultaba ARN-VHC+, se generaba una alerta a Hepatología. Además, se comparó la fase prospectiva de Intelligen-C con el periodo previo para evaluar la eficacia y la eficiencia.

ResultadosLa estrategia Intelligen-C en la fase retrospectiva permitió identificar 272 pacientes perdidos anti-VHC+/ARN-VHC+ (11 fueron tratados). En la fase prospectiva, tras realizar 7.312 serologías se identificaron 28 pacientes ARN-VHC+, 14 acudieron a consulta, 9 tratados. En la fase prospectiva vs. periodo previo aumentaron las serologías (7312 vs. 909) y la detección ARN-VHC+ (28 vs. 3), la vinculación y el acceso a tratamiento (14 vs. 1), generando ahorros al sistema sanitario relacionados con las visitas médicas. Además, la estrategia Intelligen-C resultó ser coste-efectiva.

ConclusionesLa implementación de la estrategia Intelligen-C permitió identificar a pacientes con infección oculta y nuevo diagnóstico, redujo procesos asistenciales disminuyendo costes hospitalarios asociados y demostró ser eficiente.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a significant global public health issue that affects more than 58million individuals worldwide.1 This infectious disease is associated with high levels of morbidity and mortality2 and is transmissible. Recent advancements in HCV treatment, particularly the development of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), have markedly reduced liver-related morbidity and mortality owing to their high virological response rates across all genotypes.3,4 Furthermore, DAAs have streamlined the diagnosis and follow-up care of chronic HCV patients, thereby optimizing healthcare resources and improving the overall management of the disease.5,6

According to the latest study published by Spain's Ministry of Health, the HCV seroprevalence of active infection in the population aged 20–80 years was estimated to be 0.22% (95% CI 0.12–0.32%),7 being found mainly in people aged>50 years; however, in other studies, the highest prevalence was found among individuals between the ages of 40–70 years.1 The HCV seroprevalence in the emergency department is approximately 3 times greater than that in the general population.8 Despite the known risk factors associated with HCV,9 it is estimated that 56% of the individuals who visit the emergency department are unaware that they are carriers of the infection.10 Many of these individuals do not see a healthcare provider regularly. For this reason, emergency visits can provide a unique opportunity for the detection of infections that otherwise would not be detected.8

The main ways in which public health systems and providers are striving to eliminate HCV by 2030, a goal set by the World Health Organization (WHO),11 include increasing the number of diagnoses and improving linkage to care and treatment for all infected individuals quickly. To achieve this goal, one of the main barriers that must be overcome is the underdiagnosis of infection,9 mainly owing to the delay in diagnosis and the loss of patients in the health system.12 The search for patients with undiagnosed HCV infection could be enhanced by the use of tools based on artificial intelligence (AI).13 Medical records are key to monitoring and identifying HCV-susceptible patients.14 The use of AI algorithms has the potential to improve infection detection programmes and can help speed up diagnosis in populations at risk of infection.15 AI combined with a clinical decision support system can improve the functioning of the healthcare process from detection to treatment. Likewise, it can reduce the risk of loss of patients within the health system.16 Emergency departments have proven effective for the detection of HCV,17–19 so they could be the best place to implement such AI systems.

The objective of this analysis was to evaluate the clinical, economic, and management benefits of an AI-based clinical decision support system (Intelligen-C strategy) for automated, opportunistic screening for HCV in the population of individuals aged 40–70 years at the Severo Ochoa University Hospital in Madrid, Spain, and to compare the results with those of usual clinical practice. This effort would be in line with the digitalization strategy of the National Health System (NHS) in Spain, promoted by the Ministry of Health and the Autonomous Communities to advance the digital transformation of liver diseases.20

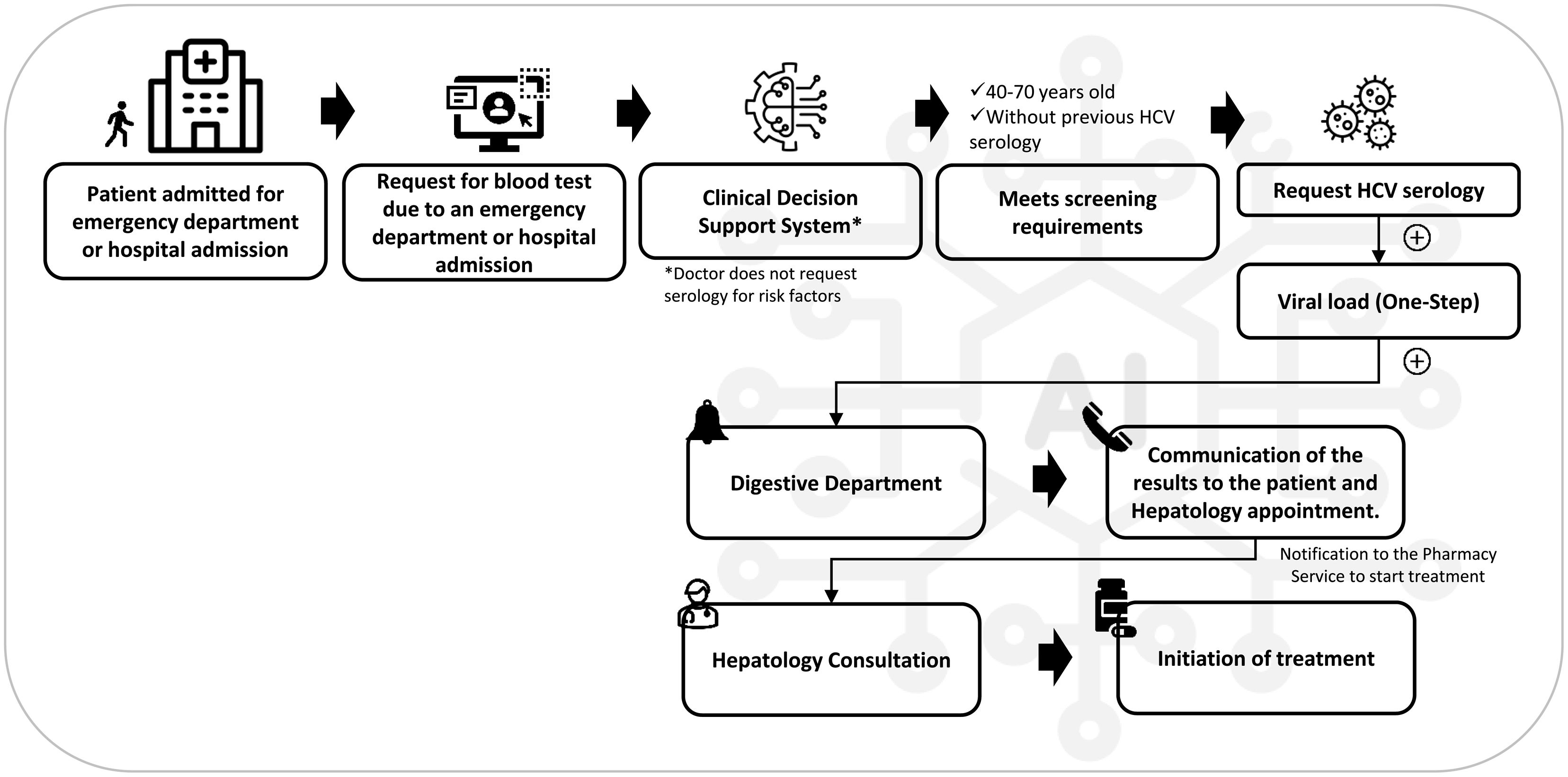

MethodsDescription of the clinical decision support systemThe clinical decision support system (CGM DISCERN), which is based on AI, adapts the hospital's processes through a series of defined actions and a programmed flow. This enables the detection of individuals who have not been diagnosed with HCV and who meet the requirements established for conducting an HCV test within the Intelligen-C strategy. The workflow was created from the guidelines of the hepatology department in collaboration with the hospital's computer systems, with multidisciplinary coordination between departments and with the support of hospital management. The methodology for its implementation in the hospital is explained in Fig. S1.

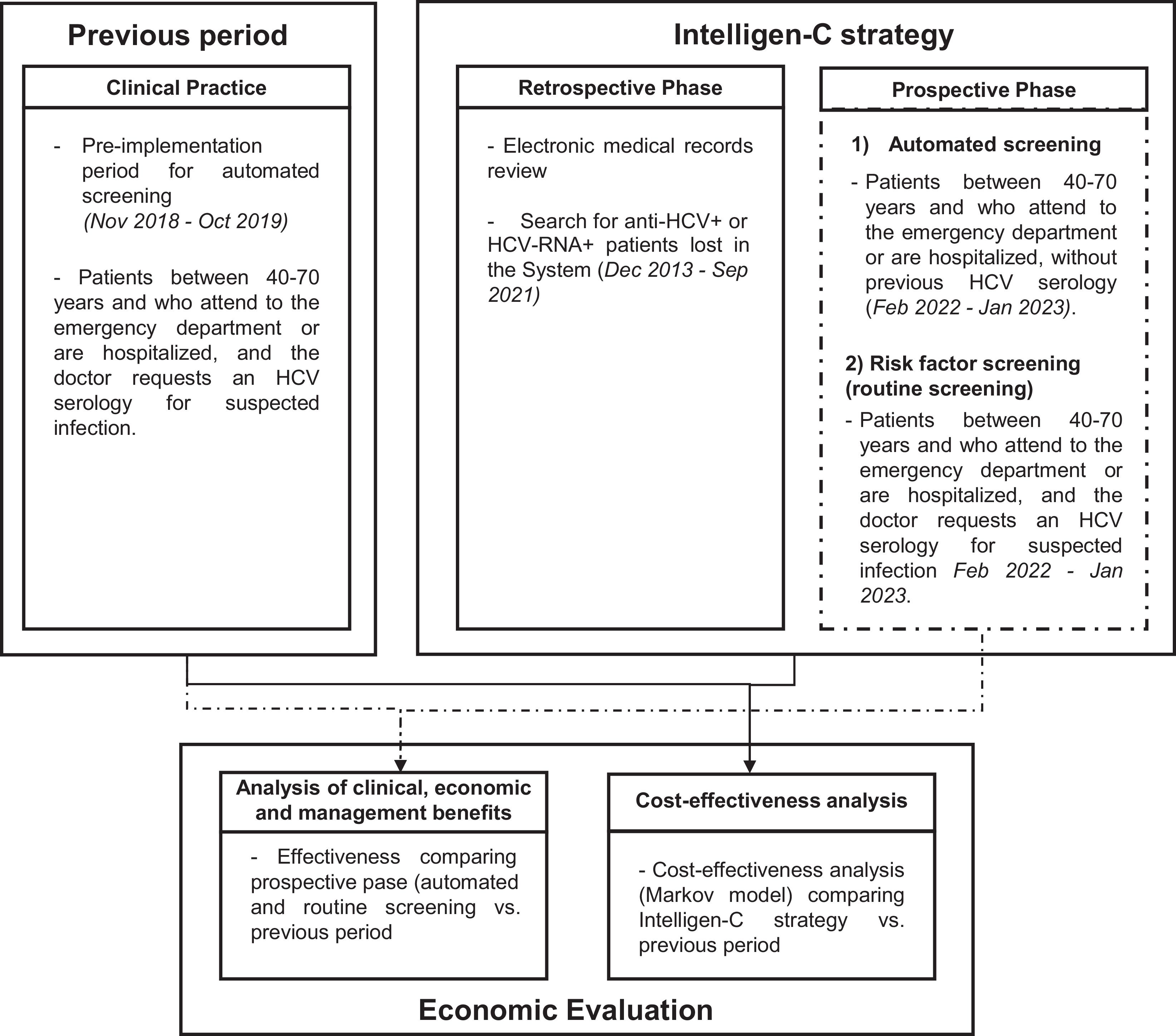

Descriptive analysisThe strategy consists of two phases, the retrospective phase and the prospective phase, with different periods. In addition, to evaluate and compare the effectiveness and efficiency of this strategy, clinical data were collected during the period preceding its implementation (previous period) (Fig. 1).

Retrospective phaseBetween December 2013 and September 2021, a retrospective search was carried out before the implementation of automated screening by reviewing the medical records of all patients at Severo Ochoa Hospital (CGM Selene), Primary Care, and José Germán Hospital to identify patients who had positive results for antibodies against HCV (anti-HCV+), had positive results for the ribonucleic acid of HCV (HCV-RNA+), or who underwent HCV treatment.

The history of the results was incorporated into the clinical records of the patients with the help of the system as a source for automated screening. Patients who were anti-HCV+ and/or HCV-RNA+ but not linked to care were contacted through several telephone calls to make appointments in the hepatology consultation.

Prospective phaseOn the basis of the AI algorithm designed with the consensus of all the stakeholders involved and complementary to screening for risk factors (routine screening), if the physician decided not to request HCV testing, automated opportunistic screening was performed on patients aged 40–70 years who came to the emergency department or were admitted to the hospital, required a blood test at their visit, and had no evidence of previous serological diagnosis for HCV. The data collection period was February 2022–January 2023.

To carry out the screening, an AI system was implemented to identify candidate patients through their electronic medical records and to request an anti-HCV serology test. If the result was positive for anti-HCV, the viral load test was automatically requested for reflex testing, and if that result was positive, an automatic alert was issued to the digestive diseases department, which referred the patient to the hepatology consultation for diagnosis, assessment, and initiation of treatment. Throughout the process, the patients were monitored to determine their status within the healthcare circuit (Fig. 2).

Information on risk factor screening (routine screening) in the emergency department and hospital admissions was also collected in this phase.

The information collected for the descriptive analysis included the number of HCV serologies performed, the numbers of anti-HCV- and HCV-RNA+ patients, the number of patients who came to the hepatology appointment, the reasons for not attending, and the number of patients who agreed to treatment.

Economic evaluationAnalysis of clinical, economic, and management benefitsThe effectiveness of the strategy, measured as the difference in the number of serologies performed, the number of HCV-RNA+ patients detected, the number of medical appointments, and the number of patients treated, was evaluated by comparing the prospective phase with the period before the implementation of automated screening (previous period) (November 2018–October 2019) (Fig. S2).

The consumption of health resources considered in the analysis included tests for screening (anti-HCV serologies) and diagnosis (HCV-RNA, laboratory tests, abdominal ultrasound, medical visit). The unit costs were obtained from the literature21 and from official sources (Table S1). The cost of emergency department visits or during the hospital admission was not considered because all patients visited the hospital for reasons other than HCV. The cost of implementing the clinical decision support system was assumed by the NHS in charge of the hospital's IT services.

Cost-effectiveness analysisA previously published Markov model22 was used to simulate the evolution of patients with chronic infection treated with the Intelligen-C strategy compared with the previous period. The clinical parameters of the fibrosis states were obtained from our study and those referring to the published model itself (transition probabilities, utilities, costs of the health states). The costs were updated to 2022 euros according to the consumer price index (CPI),23 except for the cost of treatment for HCV (€ 17,126).21 The results are presented as quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), incremental total costs, and the incremental cost/utility ratio (ICUR). The analysis was carried out from the perspective of the NHS, and a discount rate of 3% was applied to health costs and results.24

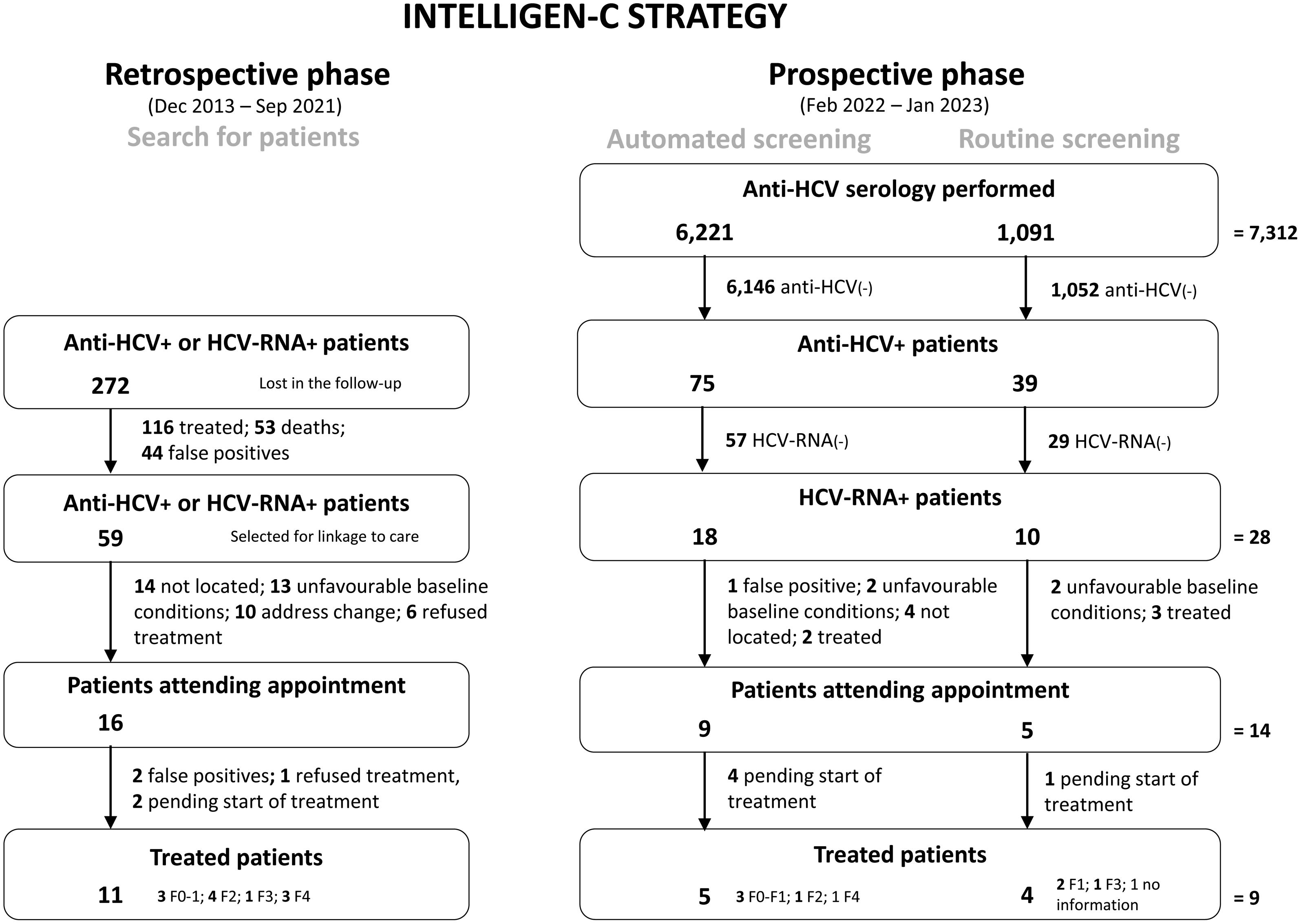

ResultsDescriptive analysisRetrospective phaseIn the retrospective phase (December 2013–September 2021), the database search revealed 272 anti-HCV- or HCV-RNA+ patients not referred to an HCV specialist, 59 of whom were selected for their location and subsequent linkage to care. Of the selected patients, 16 recovered and came to the appointment with the hepatologist, and of those, 11 were treated. The reasons for nonrecovery were as follows: 14 were not located, 13 were due to unfavourable baseline conditions, 10 were due to changes in the autonomous community or address, and 6 refused treatment. Among the patients who started treatment, 4 had advanced fibrosis (fibrosis Stage 3 or F3) or cirrhosis (fibrosis Stage 4 or F4) (Fig. 3), 2 had no risk factors but their conditions were detected at the health centre, and the other 2 had liver disease related to alcohol or drugs that was detected at the hospital.

Prospective phaseIn the prospective phase (February 2022–January 2023), with the implementation of automated opportunistic screening, a total of 6,221 anti-HCV serologies were performed on patients who came to the emergency department or were admitted to the hospital, of whom 18 (0.29%) were HCV-RNA+, 9 (50%) came to the hepatologist appointment, 5 (56%) were treated, and only 1 had cirrhosis. Of the 4 patients who did not initiate treatment, 2 missed their appointments, and 2 had hepatocellular carcinoma and were referred to another centre for liver transplantation assessment. The reasons for not linking the viraemic patients to a hepatologist were as follows: 1 patient had a false positive result (HCV antibody serology), 4 patients could not be contacted (untraceable), 2 patients were previously treated, and 2 patients had unfavourable baseline conditions (Fig. 3). Of the 5 treated patients who were identified by automated screening, 1 patient did not meet the screening criteria set forth in the Ministry of Health Guidelines and therefore would have never been identified, whereas the other 4 met the screening criteria (4 patients with hypertriglyceridaemia, including 2 patients who were drug users).

During the same period (February 2022–January 2023), 1091 HCV serologies were performed for routine screening, and 10 (0.92%) HCV-RNA+ patients were detected, of whom 5 came to the hepatology appointment (reasons for not attending: 2 unfavourable baseline conditions and 3 previously treated), and 4 were treated. The treated patients had mild or moderate fibrosis (Fig. 3).

The implementation of automated screening together with routine screening yielded the identification of 28 HCV-RNA+ patients, resulting in a prevalence of active infection in emergency department and hospital admissions of 0.38%.

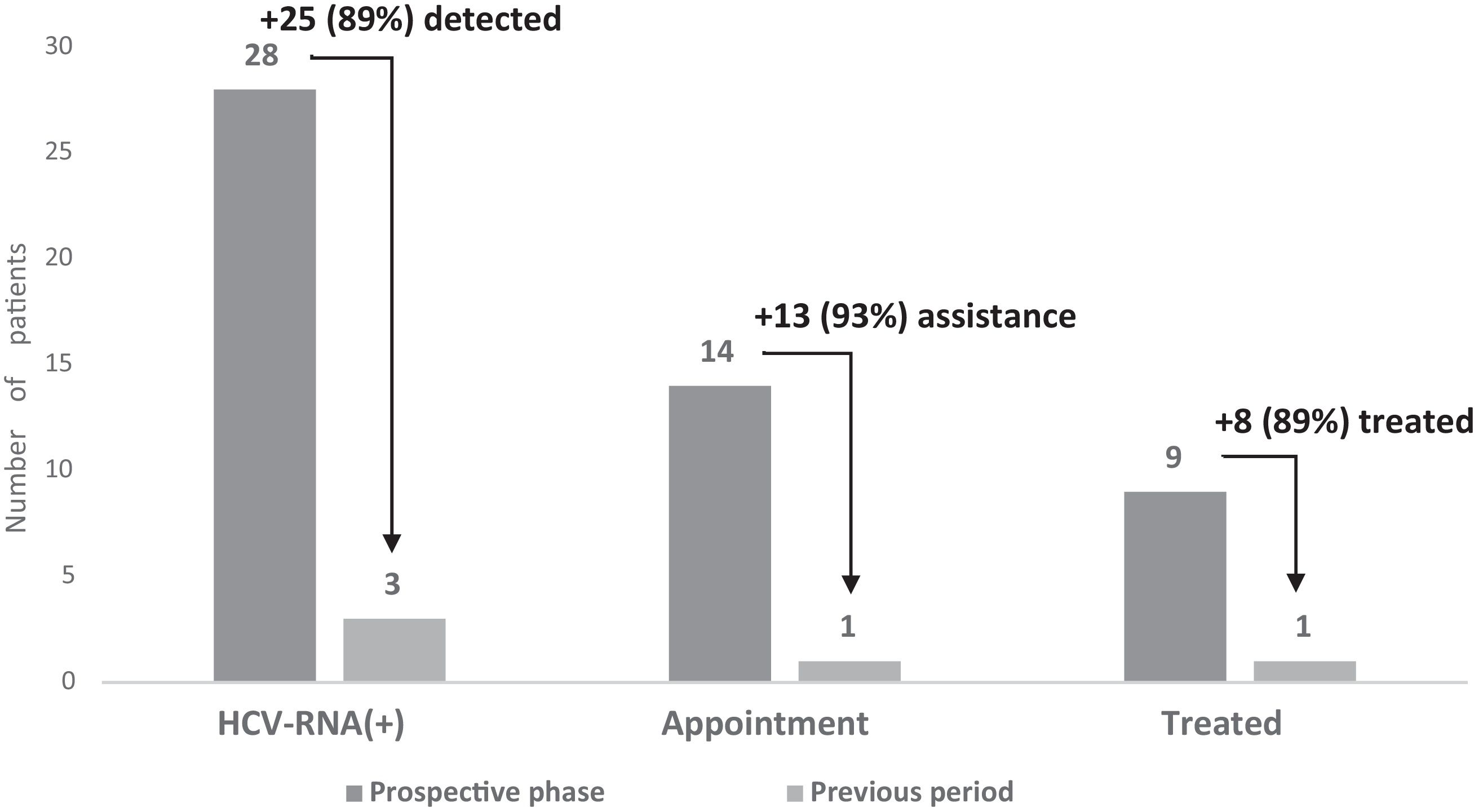

Intelligen-C strategy versus the previous period (clinical practice)With the Intelligen-C strategy, that is, considering the retrospective phase and prospective phase, a total of 87 HCV-RNA+ patients were identified, 30 patients were linked to care, and 20 patients were treated. In comparison, 909 HCV serologies were performed in the previous period (November 2018–October 2019), during which 3 HCV-RNA+ patients were identified. Only one patient in that period came to the appointment and started treatment (one patient had an unfavourable baseline condition, and the other stopped coming to the appointments) (Fig. S3).

Economic evaluationAnalysis of clinical, economic, and management benefitsCompared with the previous period, automated screening plus routine screening increased the number of HCV serologies 8-fold, the number of HCV-RNA+ patients 9-fold, the number of patients attending their appointment 14-fold, and the number of patients who started treatment 9-fold (Fig. 4).

The total cost of screening and diagnosing patients with chronic infection was € 22,815 with automated plus routine screening and € 5,494 in the previous period. Considering the total number of HCV-RNA+ patients detected (28 automated plus routine screenings vs. 3 from the previous period) and the costs, the total cost per viraemic patient detected in the prospective phase was lower than that in the previous period (clinical practice), generating savings of € 1,016 per patient detected (Table 1).

Economic results of the prospective phase (automated screening together with routine screening) versus the previous period (clinical practice).

| Prospective phase (Automated screening plus routine screening) | Previous period (Clinical practice) | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic results | Cost | Cost | Cost |

| Anti-HCV serologies | €18,134 | €2,254 | €15,879 |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Diagnostic tests | €3,616 | €1,319 | €2,297 |

| Visits | €1,065 | €1,920 | −€855 |

| Total | €22,815 | €5,494 | €17,322 |

| Cost per patient HCV-RNA+ detected | €815 | €1,831 | −€1,016 |

Cost-effectiveness analysis showed that the difference in the number of HCV-RNA+ patients treated (11 in the retrospective phase and 9 in the prospective phase with the Intelligen-C strategy vs. 1 patient in clinical practice) yielded an increase of 2.5 QALYs per patient and an increase of € 78 per patient, which represented an ICUR of € 31 for each additional QALY gained. Therefore, Intelligen-C is an efficient strategy since its costs fall below the commonly accepted efficiency threshold of € 25,000–30,00025,26 (Table 2).

Results of the cost-effectiveness analysis per patient of the Intelligen-C strategy compared with the previous period (clinical practice).

| Intelligen-C strategy (retrospective and prospective phase) | Previous period (clinical practice) | Difference (Intelligen-C strategy vs. previous period) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| QALYs | 16.9 | 14.44 | 2.5 |

| Cost | |||

| Diagnosisa | €761 | €183 | €577 |

| Pharmacological | €11,417 | €571 | €10,846 |

| Disease management (liver complications) | €8,269 | €19,615 | −€11,345 |

| Total cost | €20,447 | €20,369 | €78 |

| ICUR | €31/QALYs per patient | ||

Efforts to eliminate HCV in Spain have been successful, as 164,502 patients had been treated with DAAs as of mid-2023,14,27 but there are still undiagnosed infected patients. AI has high potential to improve detection, diagnosis, and early initiation of treatment, as well as to optimize hospital processes and continuity of care, in line with our study aims and findings.

Our analysis shows the benefits of a global strategy based on an AI system applied to improve the identification of patients at risk or suspected of HCV infection on the basis of a specific algorithm that allows the automation of screening in the age ranges with the highest prevalence of infection in the emergency department and hospital admissions. The automated screening is complementary to the performance of the test for risk factors in such a way that it is triggered only if the emergency medical specialist decides not to perform the test. One of the benefits of this strategy is the detection of patients who do not meet the criteria for risk factors according to clinical guidelines and who escape clinical notice, thus favouring the detection of undiagnosed infection. This could explain why the seroprevalence in our study was higher than that reported in an earlier seroprevalence study in Spain (0.22%)7 but lower than that reported in other studies conducted in the emergency department (0.7%).8 Likewise, the implementation of the strategy accelerated the incorporation of reflex testing diagnosis in hospitals, which, together with the AI system, allowed the monitoring of patients throughout the care process, avoiding their loss in the system. This is reflected in the results of the analysis that compared the prospective phase with usual clinical practice. This strategy promoted the search for viraemic patients lost to follow-up in the retrospective phase. Thus, in addition to linking those patients with a hepatologist, we could integrate this information into the medical records to facilitate the identification of those who had never been tested and thereby reduce the number of unnecessary HCV serologies.

The results of our study show that the Intelligen-C strategy for the detection of patients with HCV meets the objectives of digital transformation in terms of the effectiveness of detection13; support for diagnosis, clinical management, administration, or automation; improvement of workflow and communication between departments16; and reduction in healthcare costs.16,28 First, with the implementation of this strategy, the cascade of care was simplified, reducing the number of medical visits, diagnostic tests, and duplicate tests by more than half. Second, this approach shortened the time needed for diagnosis and reduced the number of administrative procedures. Although the analysis did not quantify the time related to each of the circuits, the mere simplification of the diagnosis together with the medical visits decreased the time to access treatment. Third, the automation of the process favoured communication between the different services. This is difficult to measure, but the Intelligen-C strategy made the hepatology service aware of the situation of all the patients who underwent the HCV test through flags and alerts incorporated in the algorithm and in the medical records, improving the management and identification of specific criteria for the management of the disease. As a result, economic benefits are generated by avoiding the consumption of unnecessary healthcare resources that can be reserved for attention to other patients.27

On the other hand, our analysis showed that the Intelligen-C strategy is more cost-effective than usual clinical practice. To our knowledge,29 this is the first economic evaluation of the detection, diagnosis, and access to treatment by an automated screening programme for HCV in emergency department visits and hospital admission carried out using AI in Spain. The difference from other strategies is that CGM Selene and CGM Discern automate the entire patient care circuit, from the request for a blood test to the first consultation with the hepatologist, making the work of healthcare professionals easier.8 Although there have been no economic evaluations of this type, some studies have shown, in line with our results, that strategies based on the search for patients retrospectively, alert systems, or the automation of requests are efficient.21,30,31 Likewise, studies looking only at the ability of algorithms to support decision-making or alerts without evaluating their costs are good at identifying patients at risk of infection,32,33 as we found. On the other hand, we did not evaluate hepatic events related to HCV, and there is evidence that an increase in the detection and treatment of these patients would prevent the development of complications and liver mortality and, in turn, would generate savings associated with those patients.8,34

From another point of view, the detection of and access to HCV treatment not only have economic and clinical benefits in terms of quality of life and prognosis but also have social benefits, namely, helping prevent the transmission of HCV. In our analysis, several patients detected by automated screening were intravenous drug users. This population is likely to transmit the virus, mainly through the sharing of materials. The detection and cure of the infection in these patients results in a decrease in the transmission of the virus.35 Furthermore, the hospital continues trying to locate patients who are lost in the health system, most of whom have a history of alcohol or drug use, or homelessness.

On the other hand, during the first months of the implementation of automated screening, some complications were caused that were managed throughout the process to improve the system. These differences were related to the classification between the tests run on the basis of risk factors and the automation in the microbiology laboratory, the lack of reception of the samples on weekends, and the work overload of the nursing staff caused by the implementation of the strategy. To solve these problems, several meetings were held with the microbiology service and the emergency nursing personnel to encourage the collection of blood samples and the processing of the collected samples in the laboratory on Monday. Similarly, a video class was held where the digestive disease department was available to answer any questions, explaining the study and its benefits.

Finally, it should be noted that the decision system was a key tool for the implementation of the strategy, but the transformation of hospital care processes and circuits also requires the institutional leadership of hospital management, as well as multidisciplinary coordination. These include microbiologists and nurses and the commitment of the digestive diseases department as a promoter of the strategy to define new procedures for the reuptake and screening of patients with undiagnosed HCV infection, in addition to legal and bioethical support for its implementation.

ConclusionsThe application of AI-based tools to patients treated in the emergency department and hospital wards allows the integration and structuring of the data processing of medical records to identify patients with undiagnosed HCV infection who are not detected under the criteria for risk factors established by NHS. In addition to being a cost-effective strategy, it also facilitates the early diagnosis of the disease by identifying patients in earlier stages, optimizes hospital workflows by streamlining healthcare processes (generating lower costs), allows monitoring of the patient in their follow-up through the healthcare circuit, improves the patients’ quality of life and the prognosis of the disease, and helps eliminate infection in the healthcare area in which it is implemented.

This analysis, following the purpose of the digital transformation of liver disease care in the NHS, supports the use of the HCV elimination strategy in a specific geographic area. Its extrapolation at the regional or national level would support the WHO's 2030 HCV elimination objective.

AuthorshipRDH and LSO adapted the model, reviewed the scientific literature, performed the analyses and drafted the manuscript. JLCU, MA, MV, HC, VA, JC validated the model structure and the inputs and provided information about the clinical management of hepatitis C patients. All the authors contributed to interpretation of the results and reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Artificial intelligence (AI)During the preparation of this paper, the author(s) didn’t used of AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process in their manuscript.

FundingThe study was funded by Gilead Spain Sciences.

Conflict of interestJLC: no conflict of interest.

MA: no conflict of interest.

MV, HC and VA are employees of Gilead Sciences Spain and had declared that no competing interests exist.

JC: is an employee of CGM Clinical España, S.L.U. (hereinafter ‘CGM’), a company dedicated to the development and sale of software and communication solutions, information processing products and other related products, including the provision of services, in particular aimed at electronic medical record systems for hospitals in Spain. CGM has participated as a supplier of Gilead Sciences, S.L. in this project, receiving funding from Gilead Sciences, S.L. for these services.

RDH and LSO are employees of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research Iberia (PORIB), a consulting firm specializing in the economic evaluation of health care interventions that has received financing from Gilead Sciences Spain for the development of the project that is not conditional upon the results.