The superiority between TAF and ETV remains unclear. Which is the best choice for patients with CHB? Thus, this meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of TAF and ETV for patients with CHB.

MethodsMEDLINE/PubMed, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Web of Science and CNKI were searched for eligible studies from inception to January 2024 and a meta-analysis was done.

Results24 trials with a total of 6753 subjects were screened. TAF significantly improved 12- and 24-week complete virological response (CVR), 12-week biochemical response (BR) and 24-week HBeAg loss, but could not improve 48- and 96-week CVR, 24-, 48- and 96-week BR, 96-week HBeAg loss, adverse events, 48-week HBsAg decline and loss, 12-, 24- and 48-week HBeAg seroconversion, 96-week HCC incidence compared to ETV. Subgroup analysis was conducted according to race, research type and switching. Different results were obtained from different subgroups.

ConclusionsTAF was superior to ETV at 12- and 24-week CVR, 12-week BR and 24-week HBeAg loss. Race and switching might affect the efficacy of TAF and ETV.

Se desconocen las ventajas entre tenofovir alafenamida (TAF) y entecavir (ETV) ¿Cuál es la mejor opción para los pacientes con hepatitis B crónica? Este metaanálisis tiene como objetivo evaluar la eficacia y la seguridad de TAF y ETV en los pacientes con hepatitis B crónica.

MétodoBuscar estudios elegibles desde el principio hasta enero de 2024 en: Medline/Pubmed, Biblioteca Cochrane, Embase, Web of Science y CNKI, y realizar un metaanálisis.

ResultadosSe seleccionaron 24 ensayos con un total de 6.753 sujetos. El TAF mejoró significativamente la respuesta virológica completa (CVR) a las 12 y 24 semanas, la respuesta bioquímica (BR) a las 12 semanas y la pérdida de HBeAg a las 24 semanas, pero no mejoró la CVR a las 48 y 96 semanas, la BR a las 24, 48 y 98 semanas, la pérdida de HBeAg a las 96 semanas, los eventos adversos, la disminución y la pérdida de HBeAg a las 48 semanas, la seroconversión de HBeAg a las 12, 24 y 48 semanas, la incidencia de HCC a las 96 semanas, en comparación con ETV. Análisis de subgrupos por raza, tipo de estudio y conversión. Diferentes subgrupos obtuvieron diferentes resultados.

ConclusiónTAF fue mejor que ETV cuando se perdió HBeAg a las 12 y 24 semanas CVR, 12 y 24 semanas BR. La raza y la conversión pueden afectar la eficacia de TAF y ETV.

According to the report from World Health Organization, 296million people were living with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) in 2019, with 1.5million new infections each year.1,2 CHB can lead to liver cirrhosis,3 hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)4 and even death.5 Therefore, CHB is a major global health problem. Though nucleos(t)ide (NAs), such as entecavir (ETV) and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), can slow the advance of cirrhosis, reduce HCC incidence and improve long term survival,6 few patients can achieve clinical cure.7 Therefore, new NAs should be developed.

Tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) is the 2nd Tenofovir prodrug released into the international market.8 Numerous clinical trials have consistently demonstrated that TAF has a significantly smaller impact on renal function and bone structural integrity than TDF.9 Considering the risk of drug resistance to ETV in patients exposed to lamivudine and the limitations of TDF in bone and kidney safety issues, TAF is now recommended as first-line therapy for patients with CHB.1,10

However, the evidence of efficacy and safety of long-term TAF treatment is insufficient, and the superiority between TAF and ETV remains unclear.10 It was found that different clinical trials had different results, and even the opposite results were obtained through literature search.10–33 Li and Chiu reported that TAF and ETV had similar efficacy and safety.11,13 Jung reported that ETV had a higher risk of kidney function decline than TAF.12 Peng reported that TAF was more effective than ETV in reducing viral load.14

Therefore, there is always a question that whether the efficacy and safety of TAF differ from ETV. Encouragingly, new clinical trials have been published in recent years. Hence, we conducted this comprehensive meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy and safety of TAF and ETV on patients with CHB.

MethodsThe protocol of this meta-analysis was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42024516937).

Search strategyWe searched MEDLINE/PubMed, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Web of Science and CNKI databases from inception to January 2024. The terms were “tenofovir alafenamide OR tenofovir alafenamide fumarate OR TAF”, “entecavir OR ETV”, “HBV OR hepatitis B OR CHB” in English or Chinese. Conference proceedings at the International Liver Congress and the Liver Meeting were also searched manually.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaInclusion criteria: a. all eligible patients had CHB; b. the outcomes included at least one of complete virological response (CVR), biochemical response (BR), HBsAg decline, HBeAg seroconversion, HBeAg loss, HCC incidence and adverse events (AEs); c. TAF vs ETV; d. the sample size>30; e. the follow-up time>12 weeks.

Exclusion criteria: a. combined with HCC; b. the follow-up time<12 weeks; c. repetitive articles written in different languages; d. patient treated with interferon or other NAs; e. single-arm studies; f. co-infected with HBV and HIV.

OutcomesThe CVR and BR were the primary outcomes. The CVR was defined as HBV DNA could not be detected depending on the technique. The BR was defined as normalization of ALT level. The secondary outcomes were HBeAg seroconversion, HBeAg loss, HBsAg decline, HCC incidence and AEs.

Data extraction and quality assessmentTwo reviewers assessed the quality of each study and extracted the data independently. The following data were extracted: study type, first author, outcomes, characteristics of patients, follow-up period and interventions. The risk of bias tool suggested by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions was used to assess the methodological quality of RCTs.34 The methodological quality of non-RCT was assessed by the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale.35

Statistical analysisHeterogeneity was assessed using the Q test and I2 statistic. p<0.1 and I2>50% were considered to be significant heterogeneity. The risk ratios and their 95% confidence intervals were calculated with fixed effects models when heterogeneity did not exist. However, if p<0.1 and I2>50%, random effects models were used to solve the heterogeneity between studies. If significant heterogeneity existed, a subgroup analysis was carried out to further assess it according to race, research type and switching. Publication bias was assessed statistically by Egger's and Begg's test. Sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding a single study and recalculating the pooled estimates. Stata software ver.12 was used to conduct statistical analysis. p<0.05 was considered to be significant (p values were two-sided).

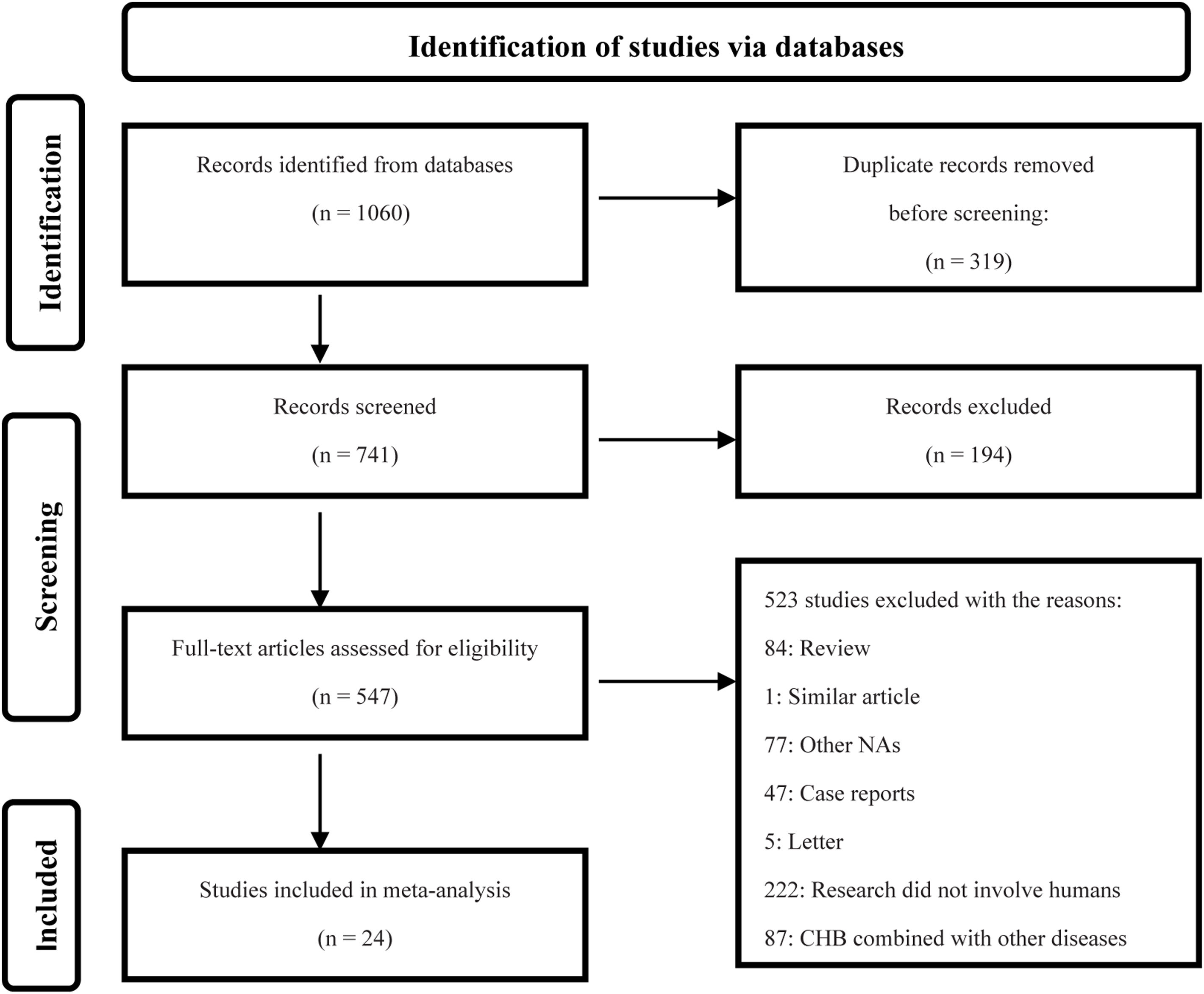

ResultsCharacteristics of studiesAs shown in the flow diagram (Fig. 1), 1060 clinical studies were identified and finally 24 studies were finalized based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

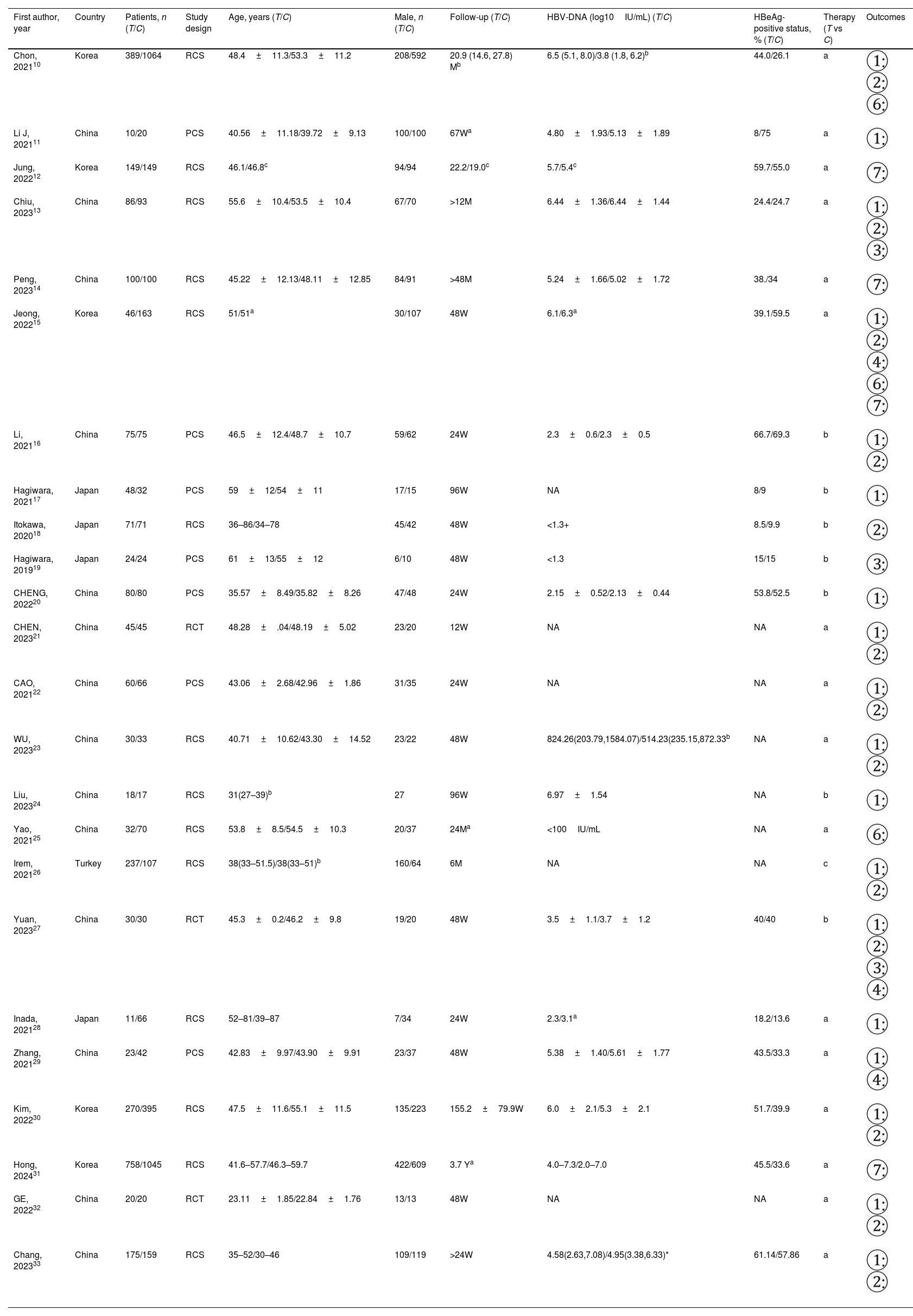

There were 6753 patients in 24 studies,10–33 which included 3 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 7 prospective cohort studies (PCSs) and 14 retrospective cohort studies (RCSs). Among them, 2787 patients were treated with TAF while 3966 with ETV. The patients mainly came from Asia. The NAs included TAF vs ETV in 16 studies, switching from ETV to TAF vs ETV in 7studies and switching from TDF to TAF vs switching from TDF to ETV in 1 study. Characteristics of studies is shown in Table 1.

The characteristics of studies.

| First author, year | Country | Patients, n (T/C) | Study design | Age, years (T/C) | Male, n (T/C) | Follow-up (T/C) | HBV-DNA (log10IU/mL) (T/C) | HBeAg-positive status, % (T/C) | Therapy (T vs C) | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chon, 202110 | Korea | 389/1064 | RCS | 48.4±11.3/53.3±11.2 | 208/592 | 20.9 (14.6, 27.8) Mb | 6.5 (5.1, 8.0)/3.8 (1.8, 6.2)b | 44.0/26.1 | a | |

| Li J, 202111 | China | 10/20 | PCS | 40.56±11.18/39.72±9.13 | 100/100 | 67Wa | 4.80±1.93/5.13±1.89 | 8/75 | a | |

| Jung, 202212 | Korea | 149/149 | RCS | 46.1/46.8c | 94/94 | 22.2/19.0c | 5.7/5.4c | 59.7/55.0 | a | |

| Chiu, 202313 | China | 86/93 | RCS | 55.6±10.4/53.5±10.4 | 67/70 | >12M | 6.44±1.36/6.44±1.44 | 24.4/24.7 | a | |

| Peng, 202314 | China | 100/100 | RCS | 45.22±12.13/48.11±12.85 | 84/91 | >48M | 5.24±1.66/5.02±1.72 | 38./34 | a | |

| Jeong, 202215 | Korea | 46/163 | RCS | 51/51a | 30/107 | 48W | 6.1/6.3a | 39.1/59.5 | a | |

| Li, 202116 | China | 75/75 | PCS | 46.5±12.4/48.7±10.7 | 59/62 | 24W | 2.3±0.6/2.3±0.5 | 66.7/69.3 | b | |

| Hagiwara, 202117 | Japan | 48/32 | PCS | 59±12/54±11 | 17/15 | 96W | NA | 8/9 | b | |

| Itokawa, 202018 | Japan | 71/71 | RCS | 36–86/34–78 | 45/42 | 48W | <1.3+ | 8.5/9.9 | b | |

| Hagiwara, 201919 | Japan | 24/24 | PCS | 61±13/55±12 | 6/10 | 48W | <1.3 | 15/15 | b | |

| CHENG, 202220 | China | 80/80 | PCS | 35.57±8.49/35.82±8.26 | 47/48 | 24W | 2.15±0.52/2.13±0.44 | 53.8/52.5 | b | |

| CHEN, 202321 | China | 45/45 | RCT | 48.28±.04/48.19±5.02 | 23/20 | 12W | NA | NA | a | |

| CAO, 202122 | China | 60/66 | PCS | 43.06±2.68/42.96±1.86 | 31/35 | 24W | NA | NA | a | |

| WU, 202323 | China | 30/33 | RCS | 40.71±10.62/43.30±14.52 | 23/22 | 48W | 824.26(203.79,1584.07)/514.23(235.15,872.33b | NA | a | |

| Liu, 202324 | China | 18/17 | RCS | 31(27–39)b | 27 | 96W | 6.97±1.54 | NA | b | |

| Yao, 202125 | China | 32/70 | RCS | 53.8±8.5/54.5±10.3 | 20/37 | 24Ma | <100IU/mL | NA | a | |

| Irem, 202126 | Turkey | 237/107 | RCS | 38(33–51.5)/38(33–51)b | 160/64 | 6M | NA | NA | c | |

| Yuan, 202327 | China | 30/30 | RCT | 45.3±0.2/46.2±9.8 | 19/20 | 48W | 3.5±1.1/3.7±1.2 | 40/40 | b | |

| Inada, 202128 | Japan | 11/66 | RCS | 52–81/39–87 | 7/34 | 24W | 2.3/3.1a | 18.2/13.6 | a | |

| Zhang, 202129 | China | 23/42 | PCS | 42.83±9.97/43.90±9.91 | 23/37 | 48W | 5.38±1.40/5.61±1.77 | 43.5/33.3 | a | |

| Kim, 202230 | Korea | 270/395 | RCS | 47.5±11.6/55.1±11.5 | 135/223 | 155.2±79.9W | 6.0±2.1/5.3±2.1 | 51.7/39.9 | a | |

| Hong, 202431 | Korea | 758/1045 | RCS | 41.6–57.7/46.3–59.7 | 422/609 | 3.7 Ya | 4.0–7.3/2.0–7.0 | 45.5/33.6 | a | |

| GE, 202232 | China | 20/20 | RCT | 23.11±1.85/22.84±1.76 | 13/13 | 48W | NA | NA | a | |

| Chang, 202333 | China | 175/159 | RCS | 35–52/30–46 | 109/119 | >24W | 4.58(2.63,7.08)/4.95(3.38,6.33)* | 61.14/57.86 | a |

T: treatment group; C: control group; W: week; M: month; Y: year; NA: not available or not-applicable; UN: unknown.

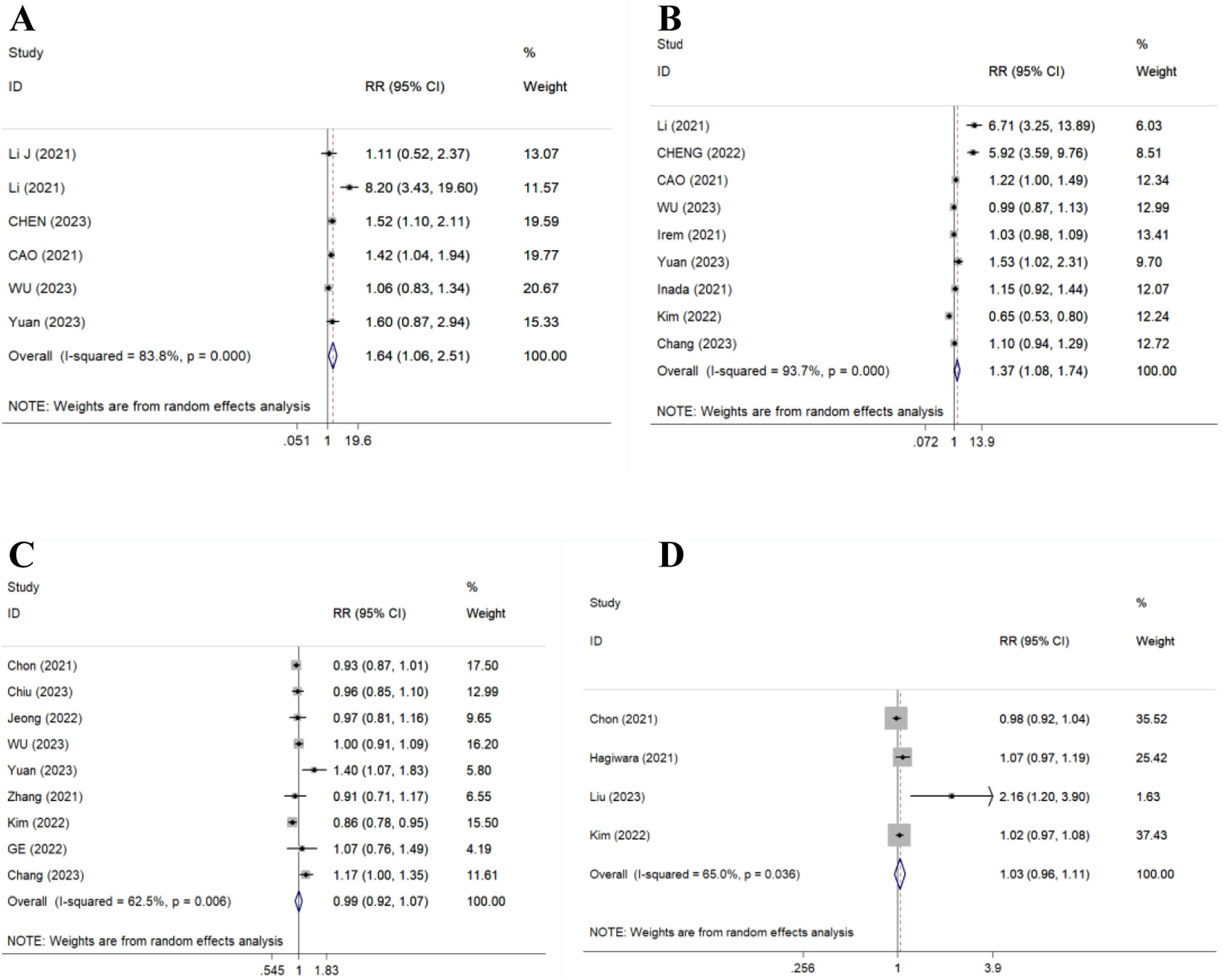

There were 6 articles (519 patients), 9 studies (1979 patients), 9 studies (3068 patients) and 4 studies (2233 patients) compared 12-, 24-, 48- and 96-week CVR, respectively. Results showed TAF significantly improved 12- and 24-week CVR (RR=1.64, 95% CI, 1.06–2.51, p=0.025, I2=83.8%; RR=1.37, 95% CI, 1.08–1.74, p=0.011, I2=93.7%) (Fig. 2A/B), but could not improve 48- and 96-week CVR compared to ETV (RR=0.99, 95% CI, 0.92–1.07, p=0.798, I2=62.5%; RR=1.03, 95% CI, 0.96–1.11, p=0.422, I2=65.0%) (Fig. 2C/D).

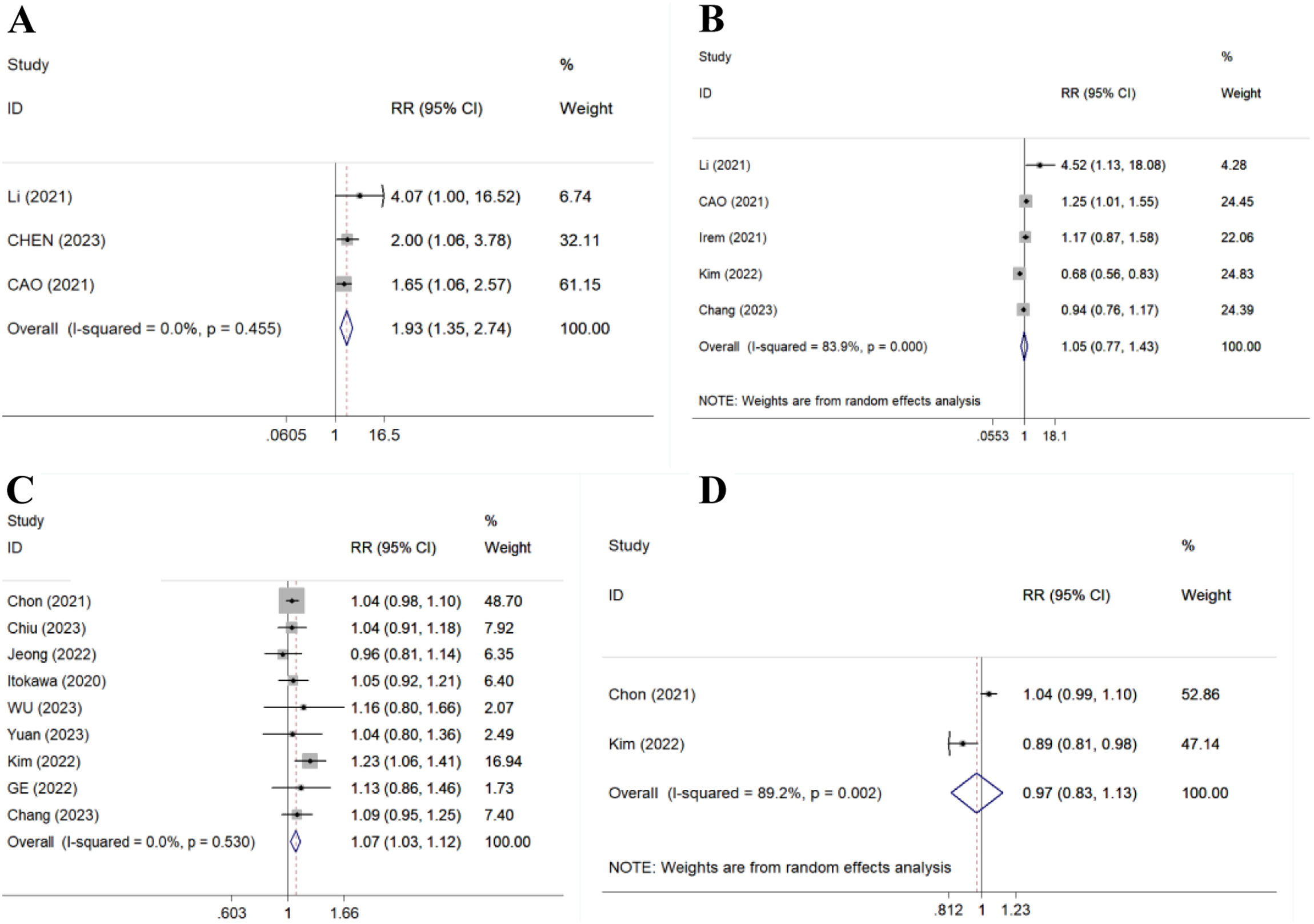

BRThere were 3 studies (366 patients), 5 studies (1619 patients), 9 studies (3145 patients) and 2 studies (2118 patients) compared 12-, 24-, 48- and 96-week BR, respectively. Results showed TAF improved 12- and 48-week BR (RR=1.93, 95% CI, 1.35–2.74, p=0.000, I2=0.0%; RR=1.07, 95% CI, 1.03–1.12, p=0.001, I2=0.0%) (Fig. 3A/C), but could not improve 24- and 96-week BR compared to ETV (RR=1.05, 95% CI, 0.77–1.43, p=0.776, I2=83.9%; RR=0.97, 95% CI, 0.83–1.13, p=0.683, I2=89.2%) (Fig. 3B/D).

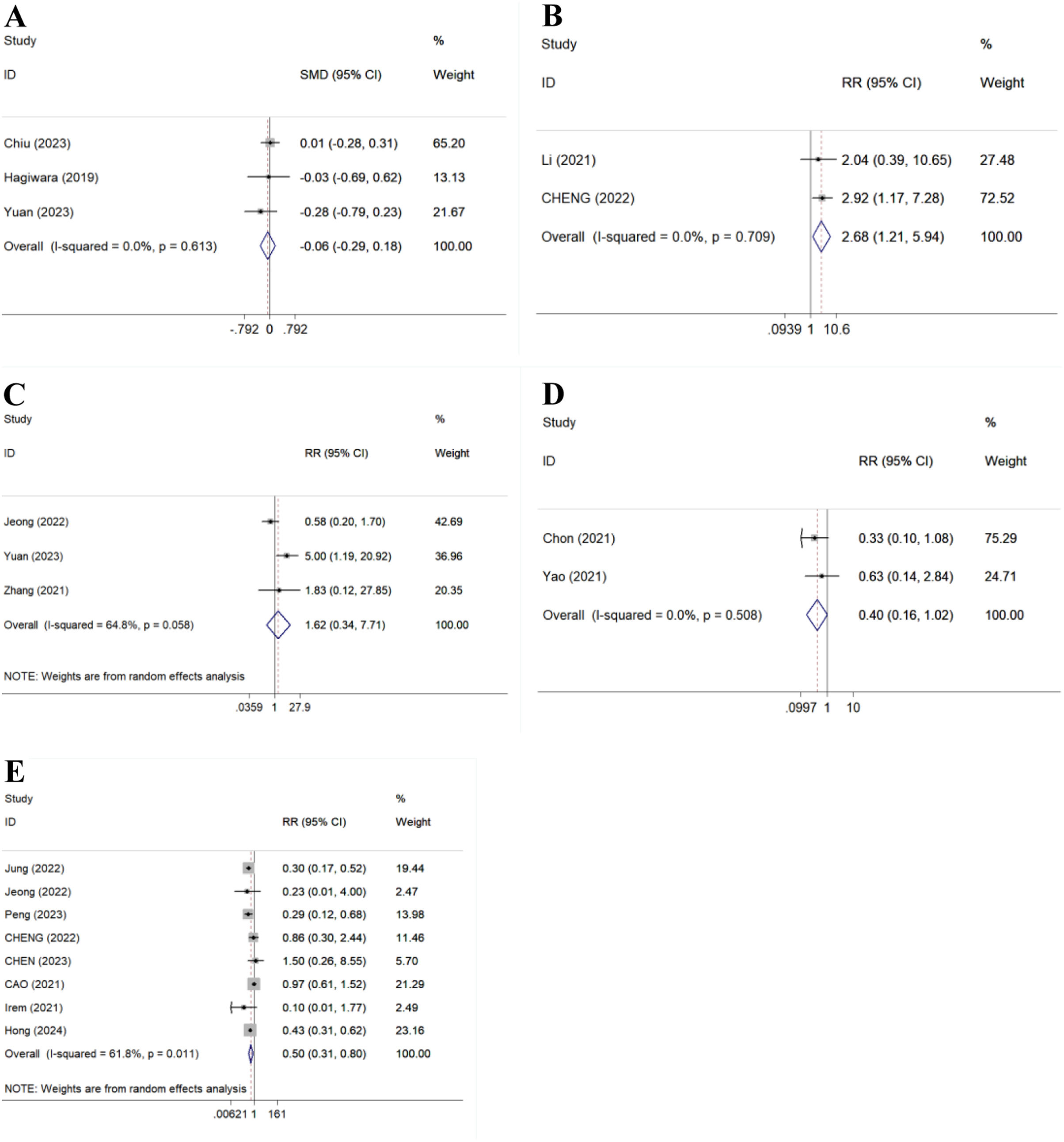

Secondary outcomesHBsAg decline and lossThere were 3 studies (287 patients) and 3 studies (188 patients) compared 48-week HBsAg decline and HBsAg loss, respectively. Result showed there was no statistical significance between TAF and ETV for 48-week HBsAg decline (SMD=−0.06, 95%CI: −0.29 to −0.18, P=0.635, I2=0.0%) (Fig. 4A). No HBsAg loss was observed in all patients.23,27,29

HBeAg loss or seroconversionThere were 2 studies (310 patients), 1 study (35 patients), 1 study (150 patients), 1 study (150 patients) and 3 studies (334 patients) compared 24- and 96-week HBeAg loss, 12-, 24- and 48-week HBeAg seroconversion, respectively. Results showed TAF improved 24-week HBeAg loss (RR=2.68, 95% CI, 1.21–5.94, p=0.015, I2=0.0%) (Fig. 4B), but could not improve 96-week HBeAg loss,24 1216-, 2416- and 48-week HBeAg seroconversion (RR=1.62, 95% CI, 0.34–7.71, p=0.544, I2=64.8%) (Fig. 4C) compared to ETV.

HCC incidenceThere were 2 studies (1555 patients) compared 96-week HCC incidence. Result showed there was no statistical significance between TAF and ETV (RR=0.40, 95% CI, 0.16–1.02, p=0.056, I2=0.0%) (Fig. 4D).

AEsThere were 8 studies (3230 patients) compared AEs. Result showed TAF significantly reduced AEs compared to ETV (RR=0.50, 95% CI, 0.31–0.80, p=0.004, I2=61.8%) (Fig. 4E).

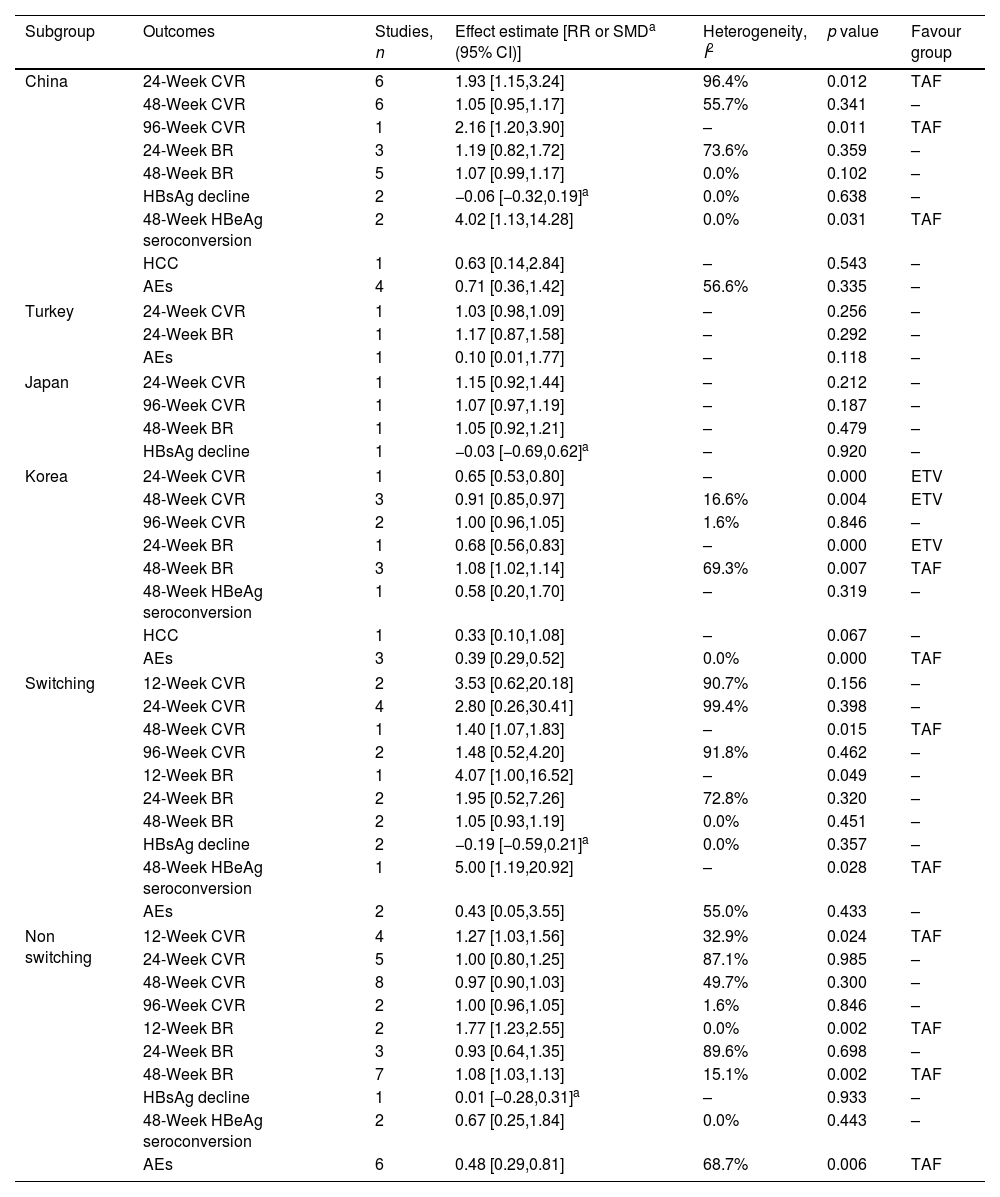

Subgroup analysisStratified analyses by regionStudies were further grouped according to region (Table 2). Results showed TAF improved 24- and 96-week CVR, 48-week HBeAg seroconversion in China subgroup, but could not improve 24- and 48-week BR, 48-week CVR and HBsAg decline, HCC incidence and AEs compared to ETV. ETV improved 24- and 48-week CVR, 24-week BR compared to TAF in Korea subgroup, but could not improve 96-week CVR, 48-week HBeAg seroconversion, HCC incidence. TAF improved 48-week BR, AEs compared to ETV in Korea subgroup. There were no statistical significances between TAF and ETV about 24- and 96-week CVR, 48-week BR and HBsAg decline in Japan subgroup. There were no statistical significances between TAF and ETV about AEs and 24-week CVR and BR in Turkey subgroup.

Stratified analyses by region and switching.

| Subgroup | Outcomes | Studies, n | Effect estimate [RR or SMDa (95% CI)] | Heterogeneity, I2 | p value | Favour group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 24-Week CVR | 6 | 1.93 [1.15,3.24] | 96.4% | 0.012 | TAF |

| 48-Week CVR | 6 | 1.05 [0.95,1.17] | 55.7% | 0.341 | – | |

| 96-Week CVR | 1 | 2.16 [1.20,3.90] | – | 0.011 | TAF | |

| 24-Week BR | 3 | 1.19 [0.82,1.72] | 73.6% | 0.359 | – | |

| 48-Week BR | 5 | 1.07 [0.99,1.17] | 0.0% | 0.102 | – | |

| HBsAg decline | 2 | −0.06 [−0.32,0.19]a | 0.0% | 0.638 | – | |

| 48-Week HBeAg seroconversion | 2 | 4.02 [1.13,14.28] | 0.0% | 0.031 | TAF | |

| HCC | 1 | 0.63 [0.14,2.84] | – | 0.543 | – | |

| AEs | 4 | 0.71 [0.36,1.42] | 56.6% | 0.335 | – | |

| Turkey | 24-Week CVR | 1 | 1.03 [0.98,1.09] | – | 0.256 | – |

| 24-Week BR | 1 | 1.17 [0.87,1.58] | – | 0.292 | – | |

| AEs | 1 | 0.10 [0.01,1.77] | – | 0.118 | – | |

| Japan | 24-Week CVR | 1 | 1.15 [0.92,1.44] | – | 0.212 | – |

| 96-Week CVR | 1 | 1.07 [0.97,1.19] | – | 0.187 | – | |

| 48-Week BR | 1 | 1.05 [0.92,1.21] | – | 0.479 | – | |

| HBsAg decline | 1 | −0.03 [−0.69,0.62]a | – | 0.920 | – | |

| Korea | 24-Week CVR | 1 | 0.65 [0.53,0.80] | – | 0.000 | ETV |

| 48-Week CVR | 3 | 0.91 [0.85,0.97] | 16.6% | 0.004 | ETV | |

| 96-Week CVR | 2 | 1.00 [0.96,1.05] | 1.6% | 0.846 | – | |

| 24-Week BR | 1 | 0.68 [0.56,0.83] | – | 0.000 | ETV | |

| 48-Week BR | 3 | 1.08 [1.02,1.14] | 69.3% | 0.007 | TAF | |

| 48-Week HBeAg seroconversion | 1 | 0.58 [0.20,1.70] | – | 0.319 | – | |

| HCC | 1 | 0.33 [0.10,1.08] | – | 0.067 | – | |

| AEs | 3 | 0.39 [0.29,0.52] | 0.0% | 0.000 | TAF | |

| Switching | 12-Week CVR | 2 | 3.53 [0.62,20.18] | 90.7% | 0.156 | – |

| 24-Week CVR | 4 | 2.80 [0.26,30.41] | 99.4% | 0.398 | – | |

| 48-Week CVR | 1 | 1.40 [1.07,1.83] | – | 0.015 | TAF | |

| 96-Week CVR | 2 | 1.48 [0.52,4.20] | 91.8% | 0.462 | – | |

| 12-Week BR | 1 | 4.07 [1.00,16.52] | – | 0.049 | – | |

| 24-Week BR | 2 | 1.95 [0.52,7.26] | 72.8% | 0.320 | – | |

| 48-Week BR | 2 | 1.05 [0.93,1.19] | 0.0% | 0.451 | – | |

| HBsAg decline | 2 | −0.19 [−0.59,0.21]a | 0.0% | 0.357 | – | |

| 48-Week HBeAg seroconversion | 1 | 5.00 [1.19,20.92] | – | 0.028 | TAF | |

| AEs | 2 | 0.43 [0.05,3.55] | 55.0% | 0.433 | – | |

| Non switching | 12-Week CVR | 4 | 1.27 [1.03,1.56] | 32.9% | 0.024 | TAF |

| 24-Week CVR | 5 | 1.00 [0.80,1.25] | 87.1% | 0.985 | – | |

| 48-Week CVR | 8 | 0.97 [0.90,1.03] | 49.7% | 0.300 | – | |

| 96-Week CVR | 2 | 1.00 [0.96,1.05] | 1.6% | 0.846 | – | |

| 12-Week BR | 2 | 1.77 [1.23,2.55] | 0.0% | 0.002 | TAF | |

| 24-Week BR | 3 | 0.93 [0.64,1.35] | 89.6% | 0.698 | – | |

| 48-Week BR | 7 | 1.08 [1.03,1.13] | 15.1% | 0.002 | TAF | |

| HBsAg decline | 1 | 0.01 [−0.28,0.31]a | – | 0.933 | – | |

| 48-Week HBeAg seroconversion | 2 | 0.67 [0.25,1.84] | 0.0% | 0.443 | – | |

| AEs | 6 | 0.48 [0.29,0.81] | 68.7% | 0.006 | TAF | |

Studies were further grouped based on whether to switch to TAF or not (Table 2). Results showed TAF improved 48-week CVR and HBeAg seroconversion in switching subgroup, but could not improve 12-, 24- and 96-week CVR, 12-, 24- and 48-week BR, 48-week HBsAg decline, AEs compared to ETV. TAF improved 12-week CVR, AEs and 12- and 48-week BR in non switching subgroup, but could not improve 24-, 48- and 96-week CVR, 24-week BR, 48-week HBsAg decline and HBeAg seroconversion compared to ETV.

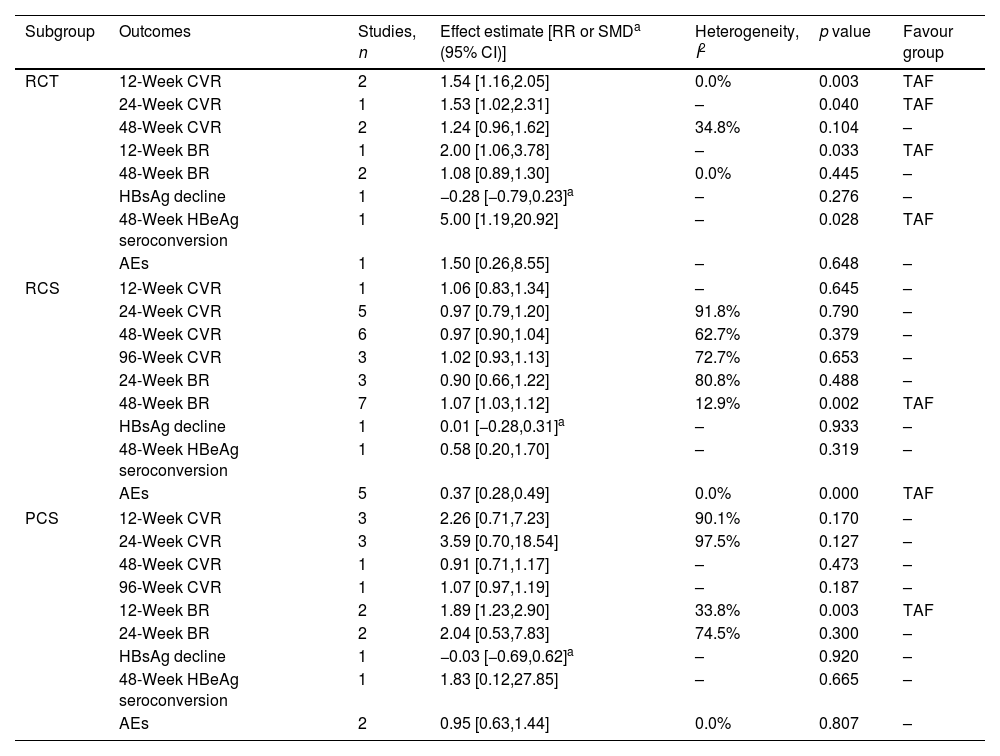

Stratified analyses by research typeStudies were further grouped according to research type (Table 3). Results showed TAF improved 12-, 24-week CVR, 12-week BR and 48-week HBeAg seroconversion in RCT subgroup, but could not improve AEs and 48-week CVR, BR and HBsAg decline compared to ETV. TAF improved 24-week LTFS, 48-week BR, AEs in RCS subgroup, but could not improve 12-, 24-, 48- and 96-week CVR, 24-week BR, 48-week HBsAg decline and HBeAg seroconversion compared to ETV. TAF improved 12-week BR in PCS subgroup, but could not improve 12-, 24-, 48- and 96-week CVR, 24-week BR, 48-week HBsAg decline and HBeAg seroconversion, AEs compared to ETV.

Stratified analyses by research type.

| Subgroup | Outcomes | Studies, n | Effect estimate [RR or SMDa (95% CI)] | Heterogeneity, I2 | p value | Favour group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCT | 12-Week CVR | 2 | 1.54 [1.16,2.05] | 0.0% | 0.003 | TAF |

| 24-Week CVR | 1 | 1.53 [1.02,2.31] | – | 0.040 | TAF | |

| 48-Week CVR | 2 | 1.24 [0.96,1.62] | 34.8% | 0.104 | – | |

| 12-Week BR | 1 | 2.00 [1.06,3.78] | – | 0.033 | TAF | |

| 48-Week BR | 2 | 1.08 [0.89,1.30] | 0.0% | 0.445 | – | |

| HBsAg decline | 1 | −0.28 [−0.79,0.23]a | – | 0.276 | – | |

| 48-Week HBeAg seroconversion | 1 | 5.00 [1.19,20.92] | – | 0.028 | TAF | |

| AEs | 1 | 1.50 [0.26,8.55] | – | 0.648 | – | |

| RCS | 12-Week CVR | 1 | 1.06 [0.83,1.34] | – | 0.645 | – |

| 24-Week CVR | 5 | 0.97 [0.79,1.20] | 91.8% | 0.790 | – | |

| 48-Week CVR | 6 | 0.97 [0.90,1.04] | 62.7% | 0.379 | – | |

| 96-Week CVR | 3 | 1.02 [0.93,1.13] | 72.7% | 0.653 | – | |

| 24-Week BR | 3 | 0.90 [0.66,1.22] | 80.8% | 0.488 | – | |

| 48-Week BR | 7 | 1.07 [1.03,1.12] | 12.9% | 0.002 | TAF | |

| HBsAg decline | 1 | 0.01 [−0.28,0.31]a | – | 0.933 | – | |

| 48-Week HBeAg seroconversion | 1 | 0.58 [0.20,1.70] | – | 0.319 | – | |

| AEs | 5 | 0.37 [0.28,0.49] | 0.0% | 0.000 | TAF | |

| PCS | 12-Week CVR | 3 | 2.26 [0.71,7.23] | 90.1% | 0.170 | – |

| 24-Week CVR | 3 | 3.59 [0.70,18.54] | 97.5% | 0.127 | – | |

| 48-Week CVR | 1 | 0.91 [0.71,1.17] | – | 0.473 | – | |

| 96-Week CVR | 1 | 1.07 [0.97,1.19] | – | 0.187 | – | |

| 12-Week BR | 2 | 1.89 [1.23,2.90] | 33.8% | 0.003 | TAF | |

| 24-Week BR | 2 | 2.04 [0.53,7.83] | 74.5% | 0.300 | – | |

| HBsAg decline | 1 | −0.03 [−0.69,0.62]a | – | 0.920 | – | |

| 48-Week HBeAg seroconversion | 1 | 1.83 [0.12,27.85] | – | 0.665 | – | |

| AEs | 2 | 0.95 [0.63,1.44] | 0.0% | 0.807 | – | |

No evidence of publication bias was detected by Begg's and Egger's test. The statistical significances were not altered by removing one study and re-analysing the data of the remaining studies, which meant the data were comparatively stable and credible.

DiscussionAt present, TAF and ETV are recommended as first-line options for patients with CHB.1 But the superiority between TAF and ETV remains unclear. Hence, this meta-analysis was conducted and valuable data were obtained that should provide valuable references and recommendations for the clinical application of TAF and ETV.

In this meta-analysis, TAF significantly improved 12- and 24-week CVR, 12- and 48-week BR, but TAF could not improve 48- and 96-week CVR and 24- and 96-week BR compared to ETV. Therefore, we suppose that the advantage of TAF in CVR and BR may gradually weaken as time goes on. However, the longest available observation period was 96-week, more clinical researches with longer observation time are needed to further support our hypothesis. In clinical practice, for patients who need to reach CVR quickly, such as hepatitis B-related acute on chronic liver failure, hepatitis B-related decompensated liver cirrhosis and CHB with severe liver injury, we recommend TAF first. TAF reduced AEs compared to ETV, but some specific AEs, such as blood lipids, renal function, calcium and phosphorus metabolism, should be further studied. TAF significantly improved 24-week HBeAg loss, but could not improve 96-week HBeAg loss, HBeAg seroconversion and the 48-week HBsAg decline or loss. Therefore, chronic hepatitis B patients with HBeAg positive were recommended to choose TAF first. However, more clinical researches with longer observation time are needed to further support our recommendation. Previous studies showed tenofovir could reduce HCC incidence compared to ETV,36 however, there is always a controversy whether the HCC incidence between TAF and ETV is different.37,38 Our study showed patients with CHB treated by TAF and ETV had similar risk of developing HCC, which was consistent with conclusion from Lee.39 However, only two studies reported 96-week HCC incidence, more clinical researches with longer observation time are needed to further support our hypothesis.

In order to further understand the comprehensive efficacy of TAF and ETV on CHB, subgroup analysis was conducted. First, studies were further grouped according to region. Results showed TAF improved 24-week CVR compared to ETV in China subgroup, which was consistent with conclusion before subgroup. But ETV improved 24-week CVR compared to TAF in Korea subgroup, and there were no statistical significances between TAF and ETV in Japan and Turkey subgroups, which was not consistent with conclusion before subgroup. The opposite results were obtained from different subgroups, which were also found in other outcomes, such as 48- and 96-week CVR, AEs and 24- and 48-week BR. It meant that race might affect the efficacy of TAF and ETV. Second, studies were further grouped according to research type. Results showed the conclusions of 12- and 28-week CVR in RCT subgroups were consistent with conclusion before subgroup, which were different from the conclusions in RCS and PCS subgroups. Given that RCT gives a higher methodological quality and higher level of evidence than RCS and PCS, we believe more in results of RCT. There were no differences between TAF and ETV about AEs and 48-week BR in RCT subgroup, and TAF improved the 48-week HBeAg seroconversion, which were not consistent with the conclusions in RCS and PCS subgroups. Similarly, we consider that the advantage of TAF in CVR and BR may gradually weaken as time goes on. TAF had advantages in 48-week HBeAg seroconversion compared to ETV. There was no difference between TAF and ETV about AEs. Third, studies were further grouped based on whether to switch to TAF or not. The results of most outcomes in non switching subgroup were consistent with conclusions before subgroup, which were different from the conclusions in switching subgroup. It meant that switching might affect the efficacy of TAF and ETV. More RCTs with High quality are needed to further observe the phenomenon.

We further analyzed heterogeneity. Subgroup analysis indicated that region, switching and research type were not significant factors affecting heterogeneity. We believe that the following factors may lead to heterogeneity. First, differences in patient characteristics. Whether the patients accompanied with cirrhosis, the application time of ETV before switching, follow-up time and HBeAg-positive rate were not exactly the same, which might influence clinical effect. Second, study design. The well designed PCS and RCS can achieve the similar effect with RCT, but not all PCSs and RCSs had high quality. Third, the difference in definition of CVR. The CVR from WU25 was defined as HBV DNA<100IU/ml. The CVR from Liu26 was defined as HBV DNA<20IU/ml. Different definitions might affect the results. Due to sample size limitation and incomplete data, we could not further perform subgroup analysis. They were also limitations of this study.

What should we do next? This meta-analysis should further encourage well designed RCTs to address these limitations. High quality RCTs with large multicenter which contain fixed characteristics of patient, the same application time of ETV before switching, longer follow-up time, and the same definition of outcomes should be conducted. More importantly, we should focus on exploring the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of large-scale treatment or even treating for all HBV infected individuals, finally providing scientific evidence for public health policies. The well designed RCTs will help us to understand the efficacy of TAF and ETV on CHB more accurately and comprehensively, finally guiding clinical application of TAF and ETV in treating CHB.

ConclusionThis meta-analysis may provide valuable data to evaluate the efficacy of TAF and ETV on CHB. The results indicated that TAF was superior to ETV at 12- and 24-week CVR, 12-week BR and 24-week HBeAg loss. But the efficacy advantage of TAF might gradually weaken as time goes on. TAF could not improve AEs, HBeAg seroconversion, 48-week HBsAg decline and loss, and 96-week HCC incidence compared to ETV. Patients with CHB who switched from ETV or TDF to TAF were less effective than those received only TAF. Race and switching might affect efficacy of TAF and ETV.

Authors’ contributionsJian-Xing Luo, Xiao-Yu Hu and Chang-Yu designed the study. Screening, review, data extraction and interpretation were done by Jian-Xing Luo, Xiao-Yu Hu, Guo Chen and Chang-Yu. Data analysis was done by Guo Chen and Chang-Yu. Jian-Xing Luo wrote the manuscript. All authors made contributions to the editing and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication. Jian-Xing Luo and Guo Chen contributed equally to this work.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

The authors are particularly grateful for the excellent professional assistance from their colleagues in Hospital of Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine.