Less than half of patients with chronic hepatitis C genotype 3 (G3) and high viral load (HVL) without a rapid virological response (RVR) achieve a sustained virological response (SVR) when treated with peginterferon plus ribavirin (RBV).

ObjectivesTo assess the impact of high doses of RBV on SVR in patients with G3 and HVL.

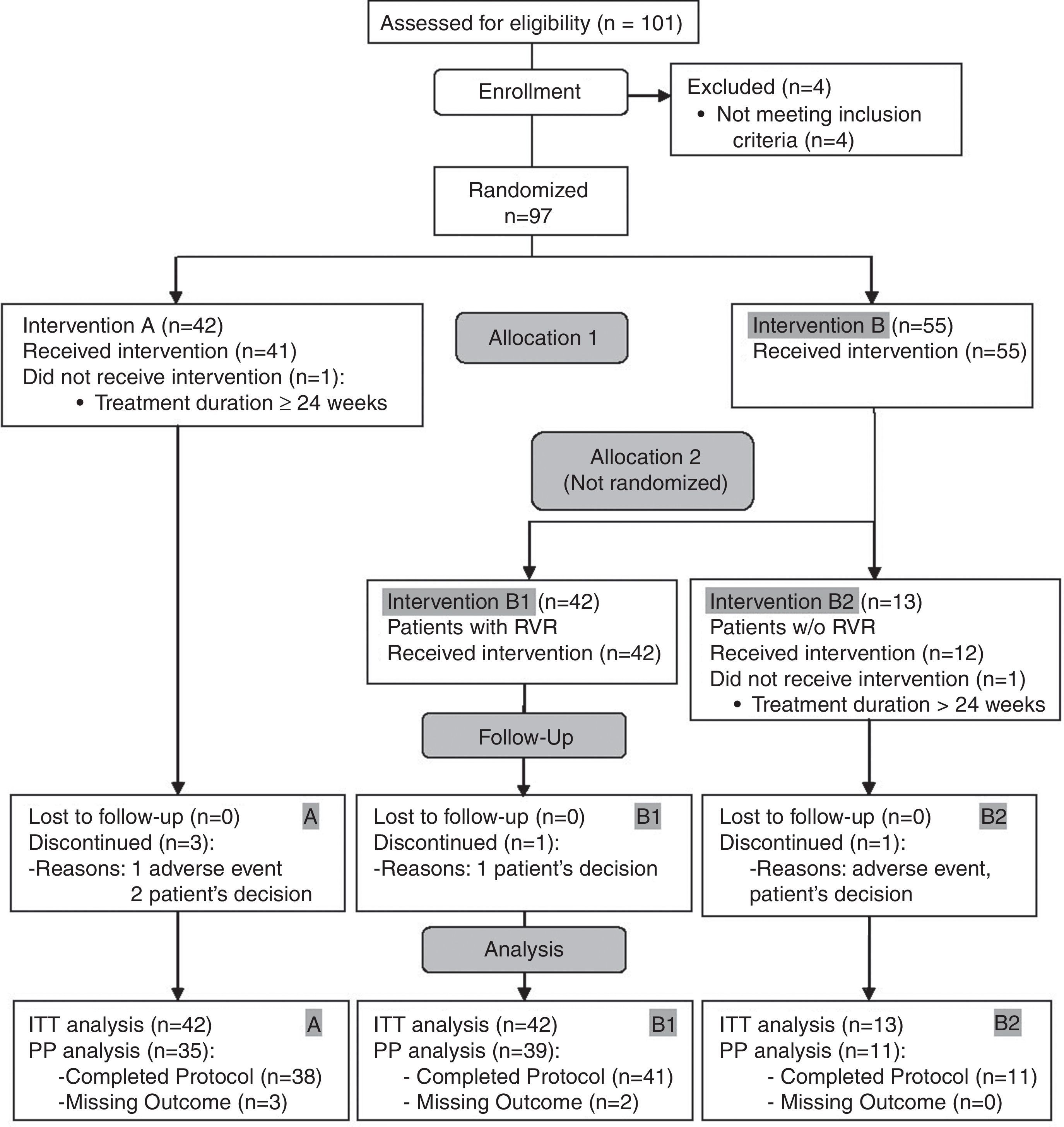

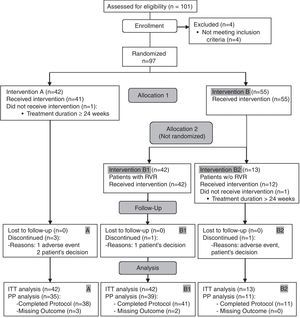

MethodsNinety-seven patients were randomized to receive peginterferon α-2a+RBV 800mg/day (A; n=42) or peginterferon α-2a+RBV 1600mg/day+epoetin β 400IU/kg/week SC (B; n=55). Patients allocated to group B who achieved RVR continued on RBV (800mg/day) for a further 20 weeks (B1; n=42) while non-RVR patients received a higher dose of RBV (1600mg/day)+epoetin β (B2; n=13).

ResultsRVR was observed in 64.3% of patients in A and in 76.4% in B (p=0.259). Intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis showed SVR rates of 64.3% (A) and 61.8% (B), with a reduction of −2.5% (−21.8% to 16.9%) (p=0.835). The SVR rate was 61.9% in arm B1 and 61.5% in arm B2. No serious adverse events were reported, and the rate of moderate adverse events was < 5%.

ConclusionsG3 patients with high viral load without RVR did not obtain a benefit from a higher dose of RBV. Higher doses of RBV plus epoetin β were safe and well tolerated (Clin Trials Gov NCT00830609).

Menos de la mitad de los pacientes con hepatitis crónica C genotipo 3 (G3) con carga viral elevada y sin respuesta virológica rápida (RVR) alcanzan respuesta virológica sostenida (RVS) con peginterferón y ribavirina (RBV).

ObjetivosEvaluar el impacto de altas dosis de RBV sobre la RVS en pacientes con G3 y carga viral elevada.

MétodosNoventa y siete pacientes recibieron asignación aleatoria para tratamiento con peginterferón α-2a+RBV800mg/día (A; n=42) o peginterferón α-2a+RBV 1600mg/día+epoetina β 400UI/kg/semana SC (B; n=55). Los pacientes asignados al grupo B que alcanzaron RVR continuaron con RBV (800mg/día) durante 20 semanas más (B1; n=42) mientras que los que no alcanzaron RVR recibieron una dosis más alta de RBV (1.600mg/día)+epoetina β (B2; n=13).

ResultadosSe observó RVR en el 64,3% de los pacientes en A y 76,4% en B (p=0,259). El análisis por intención de tratar(ITT) mostró una tasa de RVS de 64,3% (A) y 61,8% (B), con una reducción de −2,5% (−21,8–16.9%) (p=0,835). La tasa de RVS fue 61,9% en brazo B1 y 61,5% en brazo B2. No se detectaron efectos adversos graves y la tasa de efectos adversos moderados fue <5%.

ConclusionesLos pacientes G3 con carga viral elevada sin RVR no obtuvieron beneficio de dosis más altas de RBV. Las dosis más altas de ribavirina más epoetina β fueron seguras y bien toleradas. (Clin Trials Gov NCT00830609)

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 3 is the second most prevalent genotype in Europe and the USA but predominates in some geographical areas such as India and Pakistan1. Current therapy with peginterferon and ribavirin (RBV) remains the standard of care for non-G1 patients. In those infected with genotype 2 or 3, SVR rates have been found to reach 70–90% with 24 weeks of treatment2–4. Although first generation HCV protease inhibitors boceprevir and telaprevir have been licensed, these agents are not active against HCV genotype 35,6. The ACCELERATE study demonstrated that 49% of patients with G3 and without RVR achieved SVR with peginterferon alfa-2a and 800mg of RBV; most of these patients presented a baseline viral load greater than 400kIU/mL7. Extending the length of treatment to 36 or to 48 weeks in non-RVR patients did not significantly increase the SVR rate8,9. Zeuzem et al. and Hadziyannis et al. reported that 20–23% of G3 patients with VL >600kIU/ml relapsed after stopping treatment, compared to the 7% relapse rate observed in patients with baseline VL <600kIU/mL4,10. Furthermore, the dose of RBV seems to play a significant role in the rate of relapse and treatment duration11,12. Furthermore, a dose of ribavirin ranging from 1600 to 3200mg/day plus peginterferon in genotype 1, showed a 90% of SVR in a small pilot study of 10 patients13. Conversely, intensification of treatment with higher induction dose of peginterferon alfa 2 A did not improve SVR rate in a difficult-to-treat population with genotype 114. Thus, genotype 3 patients with an HVL and non-RVR showed a relatively poor SVR rate, ranging between 49% and 59%10,15. Very recent data on interferon-free regimes with sofosbuvir/ribavirin in HCV genotype 3 patients unable or unwilling to take interferon have shown SVR rates of 68% in patients without cirrhosis and 21% in patients with cirrhosis16. Extending the length of treatment has not improved the SVR rate, but higher doses of ribavirin have yet to be explored. We designed a randomized study to confirm whether a fixed higher dose of ribavirin together with epoetin β could improve the SVR rate compared to standard-of-care in a cohort of patients with chronic hepatitis C genotype 3 and baseline high viral load.

Materials and methodsStudy designDARGEN-3 (Spanish acronym for High Dose Ribavirin in Genotype 3) is a registered clinical trial (EudraCT 2008-000328-16; Clin Trials Gov Identifier NCT00830609). All procedures were approved by the Ethics Committees of the participating hospitals, and were in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. This randomized phase IV multicenter study was conducted in 21 Spanish hospitals, and compared the efficacy of high dose RBV treatment combined with standard doses of peginterferon α-2a, with the current standard treatment of RBV plus peginterferon α-2a in chronic hepatitis patients with genotype 3 HCV and high VL. Consecutive treatment naive patients with HCV infection and genotype 3 were invited to participate. Eligible patients were ≥18 years, chronically infected with HCV genotype 3 and had serum HCV-RNA ≥600kIU/ml. A negative pregnancy test in the case of women of childbearing potential and use of contraceptive measures during treatment and 6 months after completion was required. Exclusion criteria included previous treatment with immunomodulators or any experimental medicine (≤6 months), hepatic comorbidities, previous history of psychiatric disorders, autoimmune diseases, chronic pulmonary disorders, severe heart disease or vascular disorders, organ transplant, decompensated liver disease, other disorders increasing the risk of anemia, neutrophils <1500cells/mm3, platelets <90,000units/mm3 or hemoglobin <12g/dl or <13g/dl (women and men, respectively) in screening tests. All patients provided written informed consent. Patient recruitment started in June 2008 and the study ended in November 2010.

The randomization sequence was created using a computer-generated list of random numbers with a 1:1 allocation without stratification. The allocation sequence was concealed from the researcher. Enrolling and assessment for eligibility was performed in each participating center, and assignment to each treatment arm was centralized by an independent entity. Drugs were stored and dispensed at each hospital pharmacy. Peginterferon α-2a (180μg/week) was administered subcutaneously to all patients; subjects in Arm A received oral RBV (800mg/day) for 24 weeks. Patients in Arm B received oral RBV (1600mg/day) and, to prevent anemia, epoetin β (450IU/kg/week), initially for 4 weeks. The rationale for per-protocol epoetin β administration to patients receiving higher dose of ribavirin was to prevent RBV dose reduction, thus maximizing the likelihood of achieving RVR and SVR. After this 4-week period, a second regimen could be initiated based on HCV RNA results: if patients in arm B showed RVR at week 4, treatment with peginterferon α-2a (180μg/week) combined with RBV (800mg/day) was continued for an additional 20 weeks (Arm B1), whereas in patients without RVR at week 4, treatment with peginterferon α-2a (180μg/week) was combined with high RBV dose (1600mg/day) and epoetin β (450IU/kg/week), and continued for a further 20 weeks. Doses could be adjusted in case of intolerance or as assessed by the attending physician, according to protocol criteria.

Clinical and virological evaluationControl visits were scheduled at 4, 12 and 24 weeks after beginning treatment and a follow-up visit was scheduled 24 weeks after completion. Blood samples were collected at each visit and virologic and hematologic testing was performed in the same hospital where the samples were collected. Serum HCV RNA levels at baseline and at each time point were evaluated by quantitative polymerase-chain-reaction (PCR) assay (COBAS Amplicor® HCV Monitor Test v2.0; Roche Diagnostics). All the results of serum HCV-RNA quantification at week 4 had to be available within 5 days after blood extraction. HCV genotyping during screening to identify G3 patients was performed with the use of a hybridization technique. Routine hematology, biochemistry and urine tests were performed at each visit, with a complete physical examination and ophthalmoscopy. Histological assessment of eleven (11.34%) patients who underwent liver biopsy before therapy was available, as were elastography (FibroScan®, EchoSens, Paris) results for 31 (32%) patients. Fibrosis grading was carried out according to the METAVIR Score17.

Efficacy and safety assessmentThe primary end-point was the SVR rate, defined as an undetectable serum HCV RNA level 24 weeks after completion of treatment. Secondary variables were RVR, defined as an undetectable serum HCV RNA level at week 4 of treatment, and safety variables (blood tests, physical examination, record of adverse events) for high dose RBV treatment in combination with epoetin β. Virologic relapse was defined as a detectable HCV RNA level during follow-up in patients who had had undetectable HCV RNA at the end of treatment.

Statistical analysisThe expected SVR rate for standard-dose therapy (A) was 0.507 and 0.75 for the high dose strategy (B). To detect statistically significant differences with a two-sided 5% significance level and a power of 80%, a sample size of 116 patients was necessary. Given an anticipated dropouts rate of 10%, final sample size was 128.

Quantitative variables were described with measures of central tendency and dispersion (mean and standard deviation, median and interquartile range). Qualitative variables were described as absolute (n) and relative frequencies (%). Fisher's exact test was used to study differences in RVR and SVR between treatments arms. A subgroup analysis by RVR was performed and a Breslow–Day test of homogeneity was calculated.

An exploratory univariate analysis was performed to search for factors associated with the SVR rate. Variables reaching significance in univariate analysis, RVR and treatment variables were introduced in a multivariate logistic regression analysis.

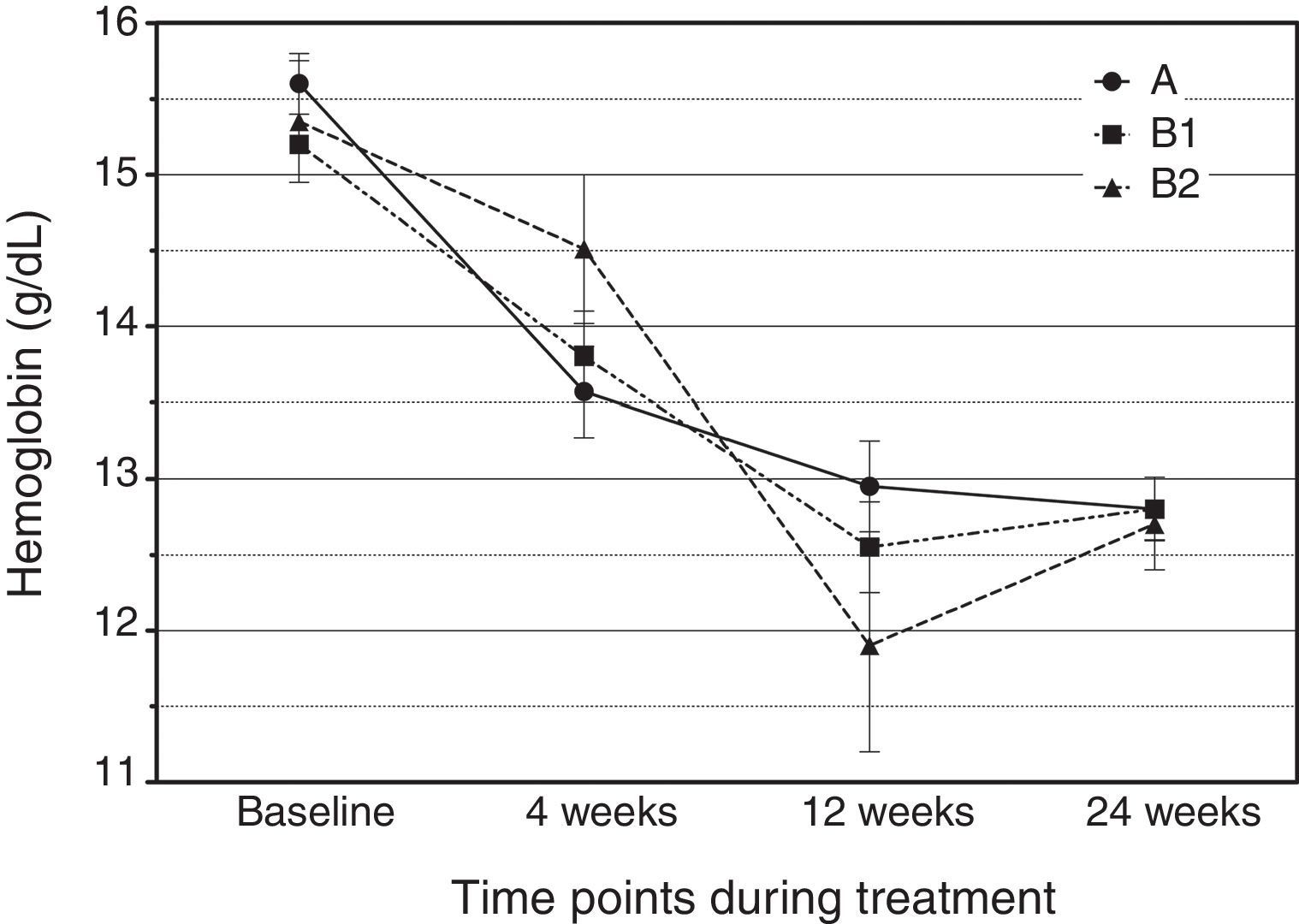

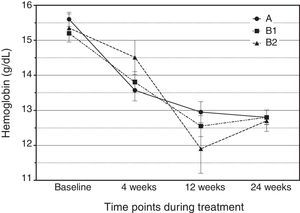

A lineal general model with repeated measures was used to study hemoglobin concentration curves: time (baseline, 4, 12 and 24 weeks after treatment) was included as intra-subject factor and treatment (A, B1, B2) was included as inter-subject factor. Any interaction effect would show significant differences between groups. Post hoc analysis was performed using the Bonferroni adjustment.

Tests were considered bilateral in all cases with a significance level of 0.05. All analyses were performed using the SPSS package version 17.

Intention-to-treat analyses included all randomized participants (n=97); missing outcomes were considered non-response.

An independent data and safety monitoring board performed an interim analysis of efficacy when 80% of the expected number of subjects had accrued and completed the follow-up; no correction of the reported p-value for this interim test was performed.

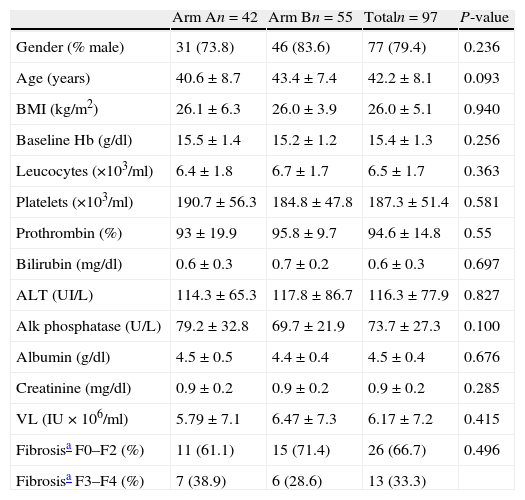

ResultsAt the time of the interim analysis, 101 patients had been recruited, four of whom were excluded as they did not meet all the inclusion criteria. Finally, 97 evaluable patients were included, of whom 42 were allocated to arm A and 55 to arm B. All patients from both arms had similar baseline demographic characteristics (Table 1). Two patients (one in each arm) were further excluded from the ITT analysis for SVR because they received treatment for a longer period than planned (Fig. 1).

Demographic characteristics and baseline laboratory data of hepatitis C genotype 3 patients in both treatment arms (mean±SD).

| Arm An=42 | Arm Bn=55 | Totaln=97 | P-value | |

| Gender (% male) | 31 (73.8) | 46 (83.6) | 77 (79.4) | 0.236 |

| Age (years) | 40.6±8.7 | 43.4±7.4 | 42.2±8.1 | 0.093 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.1±6.3 | 26.0±3.9 | 26.0±5.1 | 0.940 |

| Baseline Hb (g/dl) | 15.5±1.4 | 15.2±1.2 | 15.4±1.3 | 0.256 |

| Leucocytes (×103/ml) | 6.4±1.8 | 6.7±1.7 | 6.5±1.7 | 0.363 |

| Platelets (×103/ml) | 190.7±56.3 | 184.8±47.8 | 187.3±51.4 | 0.581 |

| Prothrombin (%) | 93±19.9 | 95.8±9.7 | 94.6±14.8 | 0.55 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.6±0.3 | 0.7±0.2 | 0.6±0.3 | 0.697 |

| ALT (UI/L) | 114.3±65.3 | 117.8±86.7 | 116.3±77.9 | 0.827 |

| Alk phosphatase (U/L) | 79.2±32.8 | 69.7±21.9 | 73.7±27.3 | 0.100 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 4.5±0.5 | 4.4±0.4 | 4.5±0.4 | 0.676 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.9±0.2 | 0.9±0.2 | 0.9±0.2 | 0.285 |

| VL (IU×106/ml) | 5.79±7.1 | 6.47±7.3 | 6.17±7.2 | 0.415 |

| Fibrosisa F0–F2 (%) | 11 (61.1) | 15 (71.4) | 26 (66.7) | 0.496 |

| Fibrosisa F3–F4 (%) | 7 (38.9) | 6 (28.6) | 13 (33.3) |

VL=viral load.

Mean±SD, n (%). P-values results of univariate analyses performed by Pearson chi-square test, Student's t-test and Mann–Whitney U-test

These percentages have been calculated including only these patients.

The trial was discontinued earlier than intended due to the result of the interim analysis which showed no differences between groups. Further recruitment would have resulted in futility.

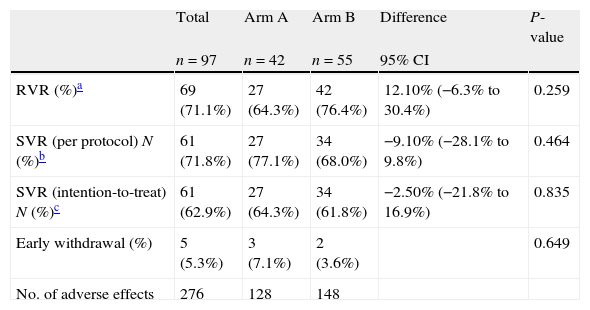

RVR was achieved by 69 out of 97 patients (71.1%). In arm A, the RVR rate was 64.3% and in arm B it was 76.4%, p=0.259. Arm B patients were re-allocated to arm B1 (n=42) and B2 (n=13) according to the RVR. At the end of treatment (week 24), 97.7% achieved a virological response, and percentages were similar in all arms, 100% (A), 95% (B1) and 100% (B2) (p=0.613).

The SVR rate by ITT analysis was 64.3% in arm A and 61.8% in arm B, p=0.835. In the PP analysis, 85 subjects who completed the protocol with no missing outcomes were included, 35 in arm A and 50 in arm B. The SVR rate was 77.1% in arm A and 68% in arm B, p=0.464 (Table 2). There were 22 Asian patients. Although RVR and SVR rates were also explored separately, results were similar in both ethnic groups: 70.5% of the Caucasian patients achieved RVR and 65.3% SVR, while 73.7% of the Asian patients presented RVR and 77.8% SVR (N.S.).

Summary of response data in patients included in both treatment arms.

| Total | Arm A | Arm B | Difference | P-value | |

| n=97 | n=42 | n=55 | 95% CI | ||

| RVR (%)a | 69 (71.1%) | 27 (64.3%) | 42 (76.4%) | 12.10% (−6.3% to 30.4%) | 0.259 |

| SVR (per protocol) N (%)b | 61 (71.8%) | 27 (77.1%) | 34 (68.0%) | −9.10% (−28.1% to 9.8%) | 0.464 |

| SVR (intention-to-treat) N (%)c | 61 (62.9%) | 27 (64.3%) | 34 (61.8%) | −2.50% (−21.8% to 16.9%) | 0.835 |

| Early withdrawal (%) | 5 (5.3%) | 3 (7.1%) | 2 (3.6%) | 0.649 | |

| No. of adverse effects | 276 | 128 | 148 |

Five patients discontinued treatment prematurely. The reasons were an adverse event in one case and the patient's decision in three (two participants in arm A and one in B1). Another non-responding patient discontinued treatment in B2 due to intolerance (p=0.649).

The overall PP SVR rate was 71.8% with no significant differences between treatment arms, with SVR rates 77.1% (A), 66.7% (B1) and 72.7% (B2) (p=0.605). According to the ITT, SVR was 64.3% (A), 61.9% (B1) and 61.5% (B2) (p=0.969).

A subgroup analyses according to RVR was performed. In patients who failed to achieve RVR, SVR was achieved in 8/13 (61.5%) patients in arm B2, compared to 5/15 (33%) in arm A, p=0.255. In patients who achieved RVR, SVR was 22/27 (81%) in arm A and 26/42 (62%) in arm B1; (p=0.11). A difference in treatment effect was observed, with a Breslow–Day test of homogeneity of p=0.026.

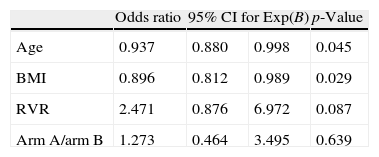

With univariate analysis, patients who attained SVR were significantly younger than non-responders (40.9±7.7 vs. 44.4±8.4 years; p=0.038). In addition, non-responders had a higher BMI than responders (27.8±4.4 vs. 25.1±5.2; p=0.017) and a lower rate of RVR than non-responders (58.3% vs. 78.7%; p=0.039) (Table 3). Unadjusted treatment effect was OR=1.11 (0.48–2.56) while logistic regression analysis showed a treatment effect after adjustment for RVR, age and BMI of OR=1.27 (0.46–3.49) (Table 4).

Univariate analysis of characteristics at baseline and the rate of rapid virological response (RVR) in patients with SVR and non-responders.

| SVR | |||

| No | Yes | p-Value | |

| n=36 | n=61 | ||

| Age (years) | 44.39±8.4 | 40.86±7.66 | 0.038 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.79±4.38 | 25.08±5.17 | 0.017 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 15.45±1.22 | 15.31±1.36 | 0.626 |

| Leukocytes/ml | 3703.78±3722.43 | 4407.8±3433.53 | 0.348 |

| Platelets/ml (×103) | 112.6±103 | 130.9±96 | 0.383 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 136.22±60.6 | 119.08±78.43 | 0.264 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 84.59±95.78 | 66.53±56.01 | 0.256 |

| ALT (IU/ml) | 111.11±57.04 | 113±92.77 | 0.912 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.66±0.28 | 0.63±0.23 | 0.511 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 4.42±0.51 | 4.47±0.39 | 0.597 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.88±0.18 | 0.86±0.14 | 0.525 |

| Baseline HCV-RNA (IU/ml) (×106) | 2.2 (1.5–5.9) | 3.7 (1.4–9.2) | 0.296 |

| Gender (Male) | 31 (86.1%) | 46 (75.4%) | 0.300 |

| RVR (%) | 21 (58.3%) | 48 (78.7%) | 0.039 |

| Fibrosis (n=39) | |||

| F0–F2 | 10 (71.4%) | 16 (64.0%) | 0.733 |

| F3–F4 | 4 (28.6%) | 8 (36.0%) | |

Mean±SD, n (%), median (P25–P75).

Liver biopsy or fibroscan was performed in 41 subjects, results were available in 39.

Logistic regression analysis.

| Odds ratio | 95% CI for Exp(B) | p-Value | ||

| Age | 0.937 | 0.880 | 0.998 | 0.045 |

| BMI | 0.896 | 0.812 | 0.989 | 0.029 |

| RVR | 2.471 | 0.876 | 6.972 | 0.087 |

| Arm A/arm B | 1.273 | 0.464 | 3.495 | 0.639 |

Variables entered: age, BMI, rapid virological response (RVR) and treatment arm (analysis of 87 patients, BMI missing in 10 patients).

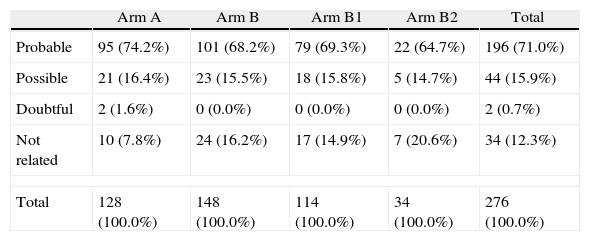

Details on the attribution of adverse events to a drug effect, classified by treatment arm and medication, are provided in Table 5. A total of 276 adverse events were reported, 87.6% of which were considered treatment-related. Notably, there were only two cases of mild anemia in arm A (4.76%) and two cases in arm B2 (17%). The rate of serious adverse events was low (n=3), with two cases of neutropenia and one case of oral aphthae. Among the overall adverse events, fatigue was the most frequently reported side effect (47.6% in arm A, 40.5% in B1 and 38.5% in B2). Fig. 2 shows hemoglobin concentrations over time. The time×treatment interaction effect was not statistically significant in the repeated measures analyses, p=0.078.

Adverse events in relation to treatment.

| Arm A | Arm B | Arm B1 | Arm B2 | Total | |

| Probable | 95 (74.2%) | 101 (68.2%) | 79 (69.3%) | 22 (64.7%) | 196 (71.0%) |

| Possible | 21 (16.4%) | 23 (15.5%) | 18 (15.8%) | 5 (14.7%) | 44 (15.9%) |

| Doubtful | 2 (1.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.7%) |

| Not related | 10 (7.8%) | 24 (16.2%) | 17 (14.9%) | 7 (20.6%) | 34 (12.3%) |

| Total | 128 (100.0%) | 148 (100.0%) | 114 (100.0%) | 34 (100.0%) | 276 (100.0%) |

| By drug and treatment arm | ||||

| pegIFN | RBV | pegIFN+RBV | Total | |

| Arm A | ||||

| Probable | 66 (80.5%) | 15 (93.8%) | 14 (77.8%) | 95 (81.9%) |

| Possible | 16 (19.5%) | 1 (6.3%) | 4 (22.2%) | 21 (18.1%) |

| Total | 82 (100.0%) | 16 (100.0%) | 18 (100%) | 116 (100%) |

| p-Value=0.414 | ||||

| ARM B1 | ||||

| Probable | 59 (86.8%) | 8 (53.3%) | 12 (85.7%) | 79 (81.4%) |

| Possible | 9 (13.2%) | 7 (46.7%) | 2 (14.3%) | 18 (18.6%) |

| Total | 68 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 14 (100%) | 97 (100%) |

| p-Value<0.05 | ||||

| ARM B2 | ||||

| Probable | 17 (81.0%) | 4 (80.0%) | 1 (100.0%) | 22 (81.5%) |

| Possible | 4 (19.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (18.5%) |

| Total | 21 (100.0%) | 5 (100.0%) | 1 (100.0%) | 27 (100%) |

| p-Value>0.0999 | ||||

p-Value (comparison A vs. B)=0.206; p-value (comparison A vs. B1 and B2)=0.276.

Rate of adverse events according to the arm of trial.

Overall results showed that treatment with high dose RBV combined with peginterferon was not more effective than standard treatment in patients with HCV genotype 3 and high viral load. This regimen was safe, as the incidence of related adverse events was not higher compared to patients on standard dose treatment. It is interesting that high RBV doses did not increase the incidence of anemia in arm B2 suggesting that epoetin β effectively prevented RBV-induced anemia18–20. Although RVR has been shown to be the strongest predictor of SVR21, and in the current study it was associated with SVR in the univariate analysis, this did not reach formal statistical significance in the multivariate analysis, which may be due to the high rate of RVR in both arms. The SVR rates found in this study were higher than those reported by Schiffman et al. in 24-week therapy7. One possible explanation is that most of our patients were Caucasian and Asian, and patients from these ethnic backgrounds have consistently achieved higher SVR rates in previous studies22–25. Nevertheless, the subgroup of patients without RVR who received high dose RBV achieved the same SVR rate as those who achieved RVR with the standard RBV dose. Although there is no trend indicating overall therapeutic advantage in arm B, twice as many patients in arm B2 achieved SVR compared with non-RVR patients in arm A (61.5% vs. 33%, p=0.25) suggesting that high-dose RBV may be effective for the sub-group of patients with HCV genotype 3 and high viral load who failed to achieve RVR, but this needs to be examined as the primary end-point in an adequately-powered prospective study.

Logistic regression analysis showed that SVR was independently associated with age and BMI. The influence of age older than 40–45 years and weight over 75kg as factors related to a negative response has been previously found in hepatitis C patients2,7. The negative influence of a high BMI could be due to the fixed RBV dose in each group, which was not weight-based, and may have caused heavier individuals to achieve relatively lower plasma RBV levels22,26. Previous studies exploring the possibility of reducing the treatment period with weight adjusted doses of ribavirin (sometimes leading to high dosage) have not found any improvement in relapse rates after short treatment either27,28.

More patients with RVR in arm A achieved SVR when compared to patients with RVR in arm B. These results suggest that induction with high dose RBV during the first 4 weeks is not useful for improving SVR rate, and a reduction in the RBV dose at week 4 may even have a negative impact on the SVR, regardless of the cumulative RBV dose received during the first 4 weeks. Recently, extending treatment with peginterferon plus ribavirin from 24 weeks to 48 weeks has not shown a better SVR rate in non-RVR patients, mainly due to the higher rate of dropouts8.

This failure to enhance SVR rates in patients infected with genotype 3, despite variations in periodicity or dosage of the best currently available therapy, highlights the need to find new approaches to address this problem. Our results failed to show a significant advantage for high-dose ribavirin in 24-week therapy over the standard dose treatment in the subgroup of patients with high baseline viral load without RVR.

Non-RVR genotype 3 patients are a difficult-to-treat group and their cure remains a challenge. New direct antiviral agents, like sofosbuvir, are expected to improve these results29,30.

Limitations to this study include its non-blinded nature and the low number of patients allocated in arm B2. In addition, the effect of high dose RBV on the SVR rate was overestimated in the calculation of the sample size when planning the trial (75% of predicted SVR).

In summary, this trial did not show benefit of high dose ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C genotype 3, high baseline viral load, and no RVR. Nevertheless, this treatment was safe when particular care was taken to prevent anemia. Further studies on the treatment of infection with HCV genotype 3 should explore forthcoming therapeutic possibilities.

Declaration of interestRoche Farma Laboratories financed the Contract Research Organization of this trial.

CFR has served as a speaker for Roche, consultant and advisory board member for BMS and MSD and an advisory board member for Janssen.

FJ has served as a speaker for Roche, MSD and Gilead and has served as an advisory board member for Gilead. MRG has served as a speaker, a consultant and an advisory board member for Roche, MSD, BMS, Janssen, Trugene, Abbott, and has received research funding from Gilead, Roche and MSD. JS has served as a speaker, a consultant and an advisory board member for Roche, Janssen and MSD. JLC has served as a speaker, a consultant and an advisory board member for MSD, Janssen, Gilead, and BMS, and has received research funding from Gilead and Roche. RS has served as a speaker, a consultant and an advisory board member for Roche, Janssen, Gilead, BMS, MSD, Novartis, and has received research funding from Roche, Gilead, BMS and MSD. RM, HM, JMN, RB, JMG, LMM, AP, MMP, FJ and TC have nothing to disclose.

Blanca Piedrafita of MSC S.L. provided medical writing support and Roche Farma S.A. financed the Contract Research Organization of this trial. The authors are grateful to Elia Perez-Fernandez from the Research Unit Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcon for methodological support. Dr. Fernandez-Rodriguez acts as guarantor of the submission. All co-authors have contributed to the recruitment of patients, gathering and submission of data. All participated in the manuscript drafting and subsequent revisions, and had complete access to the data that support the publication. All co-authors agreed with the submitted version of the manuscript.