Alteration of mismatch repair system protein expression detected by immunohistochemistry (IHQ) in tumoural tissue is a useful technique for Lynch Syndrome (LS) screening. A recent review proposes LS screening through immunohistochemical study not only in all diagnosed cases of colorectal cancer (CRC) but also in advanced adenomas, especially in young patients.

ObjectiveTo assess the prevalence of altered IHQ carried out in all adenomas with high-grade dysplasia (HGD) diagnosed in our community in 2011, as well as the variables associated with this alteration.

MethodsWe included all the cases of adenomatous polyps with HGD diagnosed in the three public pathology laboratories of Navarre during 2011 and performed a statistical study to assess the association between different patient and lesion characteristics and altered IHQ results.

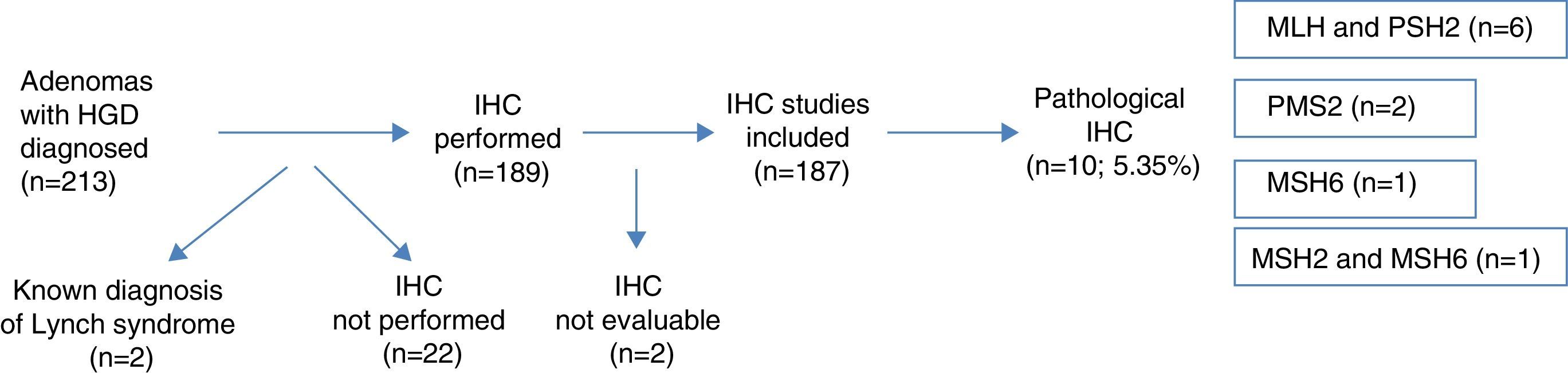

ResultsA total of 213 colonic adenomas with HGD were diagnosed, and 26 (12.2%) cases were excluded from the final analysis (2 known LS, 22 without IHQ study and 2 with inconclusive IHQ studies). The final number of adenomas included was 187. Pathologic results were found in 10 cases (5.35%)–6 cases in MLH1 and PMS2, 2 cases in PMS2, 1 case in MSH6 and 1 case in MSH2 and MSH6. The factors showing a statistically significant association with the presence of abnormal proteins were the synchronous presence of CRC, the presence of only one advanced adenoma, proximal location of HGD and age <50 years.

ConclusionsThe percentage of pathologic nuclear expression found in IHQ is high. Consequently, screening of all diagnosed HGD could be indicated, especially in young patients, with a single AA and proximal HGD.

La alteración en la expresión nuclear de proteínas de los genes reparadores del ADN valorada mediante inmunohistoquímica (IHQ) en el tejido tumoral es una técnica útil como cribado de síndrome de Lynch (SL). Una revisión reciente propone realizar este cribado no solo sobre todos los cánceres colorrectales (CCR) diagnosticados, sino también sobre adenomas avanzados (AA), especialmente en pacientes jóvenes.

ObjetivoEvaluación de la prevalencia de IHQ alterada realizada sobre todos los adenomas con displasia de alto grado (DAG) diagnosticados en nuestra comunidad durante 2011, y descripción de las variables asociadas a su alteración.

MétodosSe incluyeron todos los casos de pólipos adenomatosos con DAG diagnosticados desde los 3 laboratorios de anatomía patológica públicos de Navarra durante el año 2011, y se realizó un estudio estadístico para medir la asociación de diferentes variables, tanto de los pacientes como de las lesiones con la presencia de IHQ alterada.

ResultadosSe diagnosticaron 213 adenomas de colon con DAG, excluyéndose del análisis posterior 26 (12,2%) casos (2 SL ya diagnosticados, 22 casos sin estudio IHQ y 2 casos con IHQ no valorable), siendo el número final 187. Se encontraron hallazgos patológicos en 10 casos, suponiendo el 5,35%: 6 casos en MLH1 y PMS2, 2 casos en PMS2, un caso en MSH6 y un caso en MSH2 y MSH6. La presencia sincrónica de CCR, la presencia de un único AA, la localización proximal de la DAG y la edad <50 años resultaron estadísticamente significativos en la asociación de dichas variables, con la expresión anómala de proteínas nucleares.

ConclusionesEl porcentaje de expresión nuclear patológica hallado en la IHQ es elevado, por lo que podría estar indicado realizar screening de rutina con IHQ en todas las DAG diagnosticadas, especialmente en pacientes jóvenes, con un único AA y con DAG proximal.

Lynch syndrome (LS) is the most common hereditary form of colorectal cancer (CRC), accounting for 2–5% of all CRCs diagnosed.1,2 The lifetime risk of developing cancer in the colon or other related locations (endometrium, stomach, small intestine, hepatobiliary tract, ureter and renal pelvis) in patients with this syndrome is around 70–80%, so it is important to detect affected individuals. It is an autosomal dominant inherited disorder caused by a germline mutation in the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes, causing an accumulation of DNA replication errors. The genes most commonly implicated are MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2. Definitive diagnosis of this entity is by gene sequencing, but given the complexity and cost of this procedure, tumour tissue testing is first recommended using a molecular screening technique: microsatellite instability (MSI) study and/or immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining for MMR proteins in tumour tissue samples.3

In recent years, thanks to advances made in the molecular and genetic detection and study of both pre-neoplastic lesions and CRC, CRC is considered a heterogeneous disease, both in its pathogenesis and in its clinical manifestation and response to treatment.4 With respect to tumorigenesis, there are currently 3 accepted carcinogenesis pathways: the chromosomal instability pathway, the microsatellite instability pathway, and the serrated pathway.

It has been suggested that the latter could be responsible for between 15% and 30% of CRCs, with serrated polyps (hyperplastic polyps, sessile serrated adenomas [SSA] and traditional serrated adenomas) considered as precursor lesions.5 In some cases, the molecular alterations underlying this pathway affect the promoter region of the MMR genes, especially the MLH1 gene, leading to a similar loss of nuclear expression of MLH1 and PMS2 in IHC analysis and development of MSI as that observed in individuals with a germline mutation in that gene. It is therefore important to bear this in mind when interpreting pathological nuclear expression of MLH1 and MSI during molecular screening for LS. An increased risk of presence of MSI in SSAs, with a distal-proximal gradient, has been recently described.6 Whether the synchronous presence of these serrated polyps is associated with an increased risk of presenting pathological nuclear expression of MMR proteins in adenomas with high-grade dysplasia (HGD) remains unclear.

In 2009, the Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention working group included recommendations for universal screening of LS with MSI or IHC in all CRCs diagnosed.7 This strategy has not been routinely implemented in hospitals, with abnormal IHC/MSI results of around 12–21% reported in different studies, even with far from optimal screening rates.

A more recent topic of debate has been the benefit of performing the same screening on pre-neoplastic lesions, i.e. conventional adenomas. Some groups have reported discouraging results from MSI study of recently established adenomas.10 However, studies on patients with a known mutation for LS, in whom an IHC and/or MSI study was performed on resected adenomatous polyps, report abnormal results in between 50% and 80% of patients.11–14 These studies suggest that not all adenomas have a risk of presenting abnormal IHC/MSI results, suggesting that testing be performed on adenomas with certain characteristics (size >10mm or presence of HGD).

In a 2015 review, which examined the key points for improving the early detection and prevention of CRC in high risk families, the authors drew attention to the lack of studies evaluating a universal screening strategy for LS in pre-neoplastic lesions, and suggest performing IHC or MSI testing on advanced adenomas (>1cm, villous component or HGD) in patients aged under 40 or 50 years as a possible strategy.15 After reviewing the literature, which reports percentages close to 100% of pathological expression of MMR proteins in adenomas with HGD in carriers of the mutation,11,12 we decided to investigate and report on this specific type of polyp.

The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of loss of nuclear expression in repair proteins by performing an IHC study of all adenomas with HGD diagnosed in the Navarra region public health network, and to assess the characteristics of patients with pathological expression of these proteins and the possible association with synchronous serrated polyps (SP).

Materials and methodsThis was an observational, retrospective, population-based multicentre study in which we analysed data from all patients in whom an advanced adenoma (AA) with HGD had been detected by colonoscopy, surgical specimen or autopsy in the Navarra public health service in 2011.

ImmunohistochemistryWe collected all cases of AA with HGD diagnosed between 1 January and 31 December 2011 from the archives of 3 histopathology laboratories. HGD was defined as adenomas that presented severe dysplasia, adenocarcinoma in situ or intramucosal adenocarcinoma.

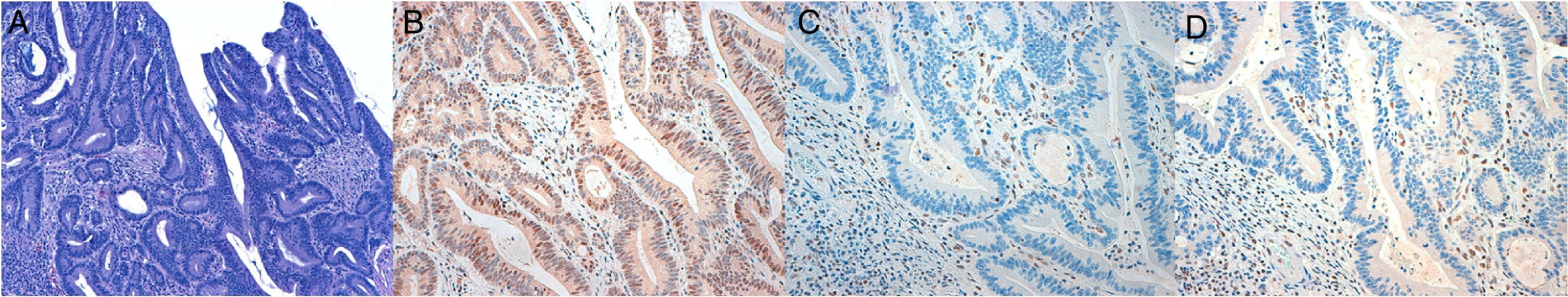

IHC testing was performed for MLH1, MSH2, PMS2 and MSH6 using prediluted and concentrated monoclonal antibodies from Leica-Biocare on tissue fixed in formaldehyde and embedded in 3μ paraffin slices. Nuclear staining in the tumour cells was reported as presence of expression, and no staining as absence of expression. Lymphocytes from non-tumour colonic tissue were used as an internal positive control. The IHC stains were interpreted by 4 pathologists with extensive experience in gastrointestinal tract pathology.

We also collected epidemiological data on the patients diagnosed (age, sex), as well as the characteristics of the colonoscopy or specimen (synchronous presence of CRC, other AA or serrated polyps, morphology, location and size of the polyp under study). Proximal location was defined as polyps found proximal to the descending colon.

The study protocol was approved by the Clínica de Navarra research ethics committee in 2011 (Project 70/11), allowing anonymous collection of the data included in the study.

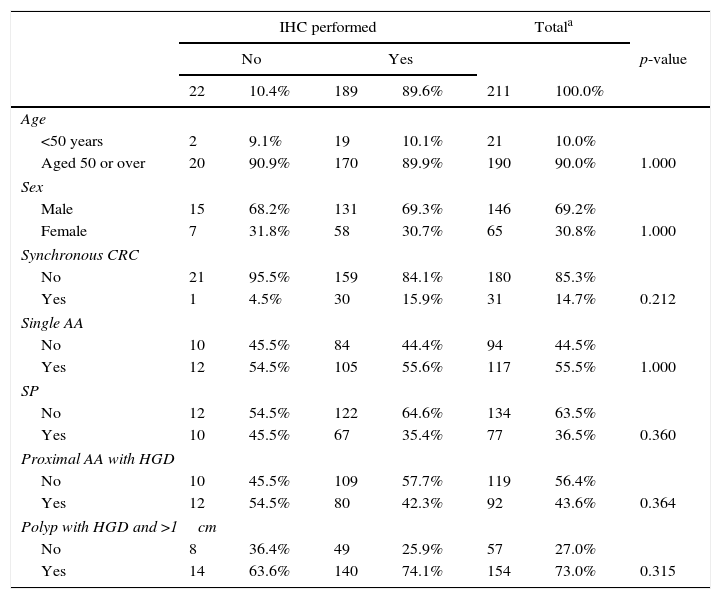

Statistical studyAll records of AA with HGD obtained were analysed using the statistics programme SPSS version 22.0 We initially checked that patients who had not had an IHC study presented the same characteristics in the variables of interest as those who had undergone this study, confirming that the criteria for performing IHC did not follow a specific pattern (Table 1).

Descriptive analysis of the whole study sample and comparison of cases with and without immunohistochemistry (IHC).

| IHC performed | Totala | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | p-value | |||||

| 22 | 10.4% | 189 | 89.6% | 211 | 100.0% | ||

| Age | |||||||

| <50 years | 2 | 9.1% | 19 | 10.1% | 21 | 10.0% | |

| Aged 50 or over | 20 | 90.9% | 170 | 89.9% | 190 | 90.0% | 1.000 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 15 | 68.2% | 131 | 69.3% | 146 | 69.2% | |

| Female | 7 | 31.8% | 58 | 30.7% | 65 | 30.8% | 1.000 |

| Synchronous CRC | |||||||

| No | 21 | 95.5% | 159 | 84.1% | 180 | 85.3% | |

| Yes | 1 | 4.5% | 30 | 15.9% | 31 | 14.7% | 0.212 |

| Single AA | |||||||

| No | 10 | 45.5% | 84 | 44.4% | 94 | 44.5% | |

| Yes | 12 | 54.5% | 105 | 55.6% | 117 | 55.5% | 1.000 |

| SP | |||||||

| No | 12 | 54.5% | 122 | 64.6% | 134 | 63.5% | |

| Yes | 10 | 45.5% | 67 | 35.4% | 77 | 36.5% | 0.360 |

| Proximal AA with HGD | |||||||

| No | 10 | 45.5% | 109 | 57.7% | 119 | 56.4% | |

| Yes | 12 | 54.5% | 80 | 42.3% | 92 | 43.6% | 0.364 |

| Polyp with HGD and >1cm | |||||||

| No | 8 | 36.4% | 49 | 25.9% | 57 | 27.0% | |

| Yes | 14 | 63.6% | 140 | 74.1% | 154 | 73.0% | 0.315 |

AA: advanced adenoma; CRC: colorectal cancer; HGD: high-grade dysplasia; SP: serrated polyp.

We then carried out the univariate study, considering abnormal/normal IHC in the study as the primary endpoint, using Fisher's exact test in the case of dichotomous variables (2 categories) and the Chi square statistic in the case of categorical variables with more than 2 categories and with expected values greater than 5.

Finally, multivariate analysis was performed by logistic regression, with abnormal/normal IHC as the dependent variable. The final model selected included the variables that best discriminated the cases of abnormal IHC.

ResultsA total of 213 patients presenting adenomas with HGD were identified in 2011 in the histopathology laboratories of the Navarra region public health network. Two of the cases were removed from the analysis as they had been previously diagnosed with LS. IHC study was performed in 189 cases (the use of this technique is still not completely systematic for HGD in our region), and we verified whether the presence or absence of IHC testing was associated with a particular characteristic (Table 1). The results of the IHC were not evaluable in 2 cases, so they were also eliminated from the analysis (Fig. 1).

Of the 187 patients (87.8%) who were eventually included in the analysis, 69.0% (129) were men and 31.0% (58) were women. Mean age of study patients was 67.4 years (SD: 11.89), ranging from 27 to 88 years; 9.6% (18) were aged <50 years, while the remaining 90.4% (169) were over 50.

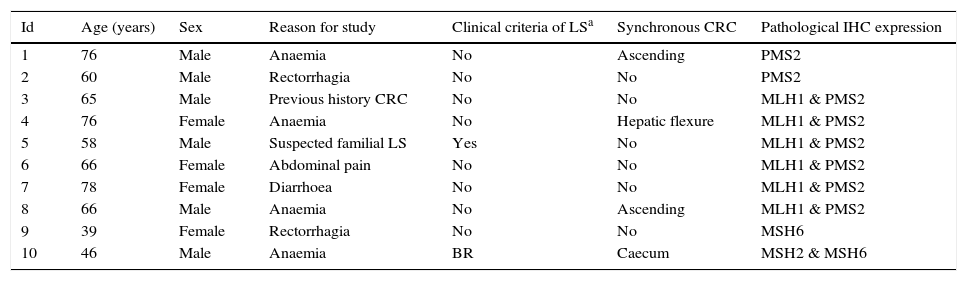

Nuclear IHC expression was pathological in 10 cases (5.35%), presenting abnormal staining for MLH1 and PMS2 in 6 cases, PMS2 alone in 2 cases, MSH6 in 1 case, and MSH2 and MSH6 in 1 case (Figs. 1 and 2). The characteristics of the 10 patients with abnormal study findings are shown in Table 2. Of the 10 cases with abnormal proteins, 6 were men and 4 women. Four of the cases were synchronously associated with CRC. In 8 cases, the reason for the colonoscopy was the presence of symptoms (4 for anaemia, 2 for rectorrhagia, 1 for abdominal pain and 1 for diarrhoea), while the remaining 2 patients were subject to follow-up programmes (one from a family who met criteria for LS and another for follow-up of CRC). The patient from the family with LS met clinical criteria for suspicion (Amsterdam II/revised Bethesda), while of the rest of the patients with pathological IHC (9 cases), only 1 met the revised Bethesda criteria.

Individual descriptions of cases with abnormal immunohistochemistry.

| Id | Age (years) | Sex | Reason for study | Clinical criteria of LSa | Synchronous CRC | Pathological IHC expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 76 | Male | Anaemia | No | Ascending | PMS2 |

| 2 | 60 | Male | Rectorrhagia | No | No | PMS2 |

| 3 | 65 | Male | Previous history CRC | No | No | MLH1 & PMS2 |

| 4 | 76 | Female | Anaemia | No | Hepatic flexure | MLH1 & PMS2 |

| 5 | 58 | Male | Suspected familial LS | Yes | No | MLH1 & PMS2 |

| 6 | 66 | Female | Abdominal pain | No | No | MLH1 & PMS2 |

| 7 | 78 | Female | Diarrhoea | No | No | MLH1 & PMS2 |

| 8 | 66 | Male | Anaemia | No | Ascending | MLH1 & PMS2 |

| 9 | 39 | Female | Rectorrhagia | No | No | MSH6 |

| 10 | 46 | Male | Anaemia | BR | Caecum | MSH2 & MSH6 |

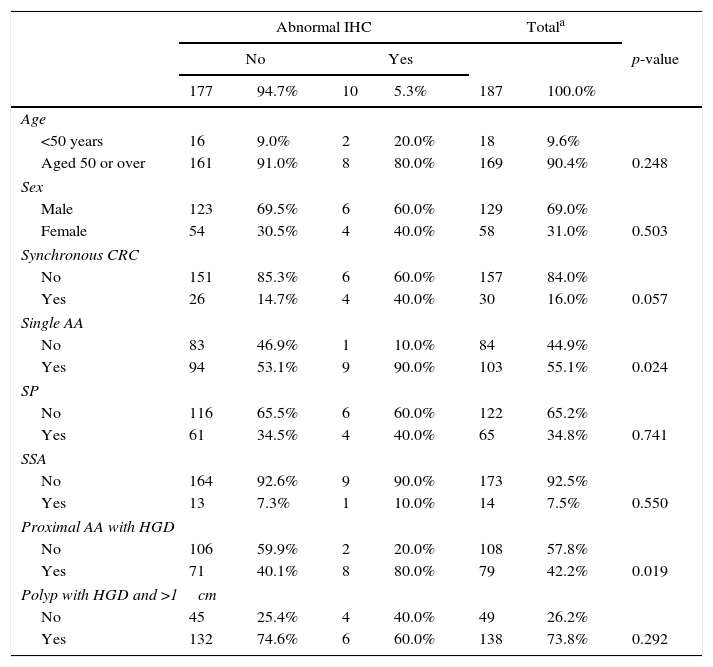

In the univariate analysis, a significant association was observed between abnormal nuclear IHC and the presence of a single AA, as well as the proximal location of polyps with HGD. The presence of synchronous CRC showed results close to statistical significance, so it was added later to the multivariate model. In contrast, age, sex, presence of serrated polyps in general, and SSAs specifically, and size of the polyp >1cm were not significant (Table 3).

Univariate analysis of abnormalities in immunohistochemistry.

| Abnormal IHC | Totala | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | p-value | |||||

| 177 | 94.7% | 10 | 5.3% | 187 | 100.0% | ||

| Age | |||||||

| <50 years | 16 | 9.0% | 2 | 20.0% | 18 | 9.6% | |

| Aged 50 or over | 161 | 91.0% | 8 | 80.0% | 169 | 90.4% | 0.248 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 123 | 69.5% | 6 | 60.0% | 129 | 69.0% | |

| Female | 54 | 30.5% | 4 | 40.0% | 58 | 31.0% | 0.503 |

| Synchronous CRC | |||||||

| No | 151 | 85.3% | 6 | 60.0% | 157 | 84.0% | |

| Yes | 26 | 14.7% | 4 | 40.0% | 30 | 16.0% | 0.057 |

| Single AA | |||||||

| No | 83 | 46.9% | 1 | 10.0% | 84 | 44.9% | |

| Yes | 94 | 53.1% | 9 | 90.0% | 103 | 55.1% | 0.024 |

| SP | |||||||

| No | 116 | 65.5% | 6 | 60.0% | 122 | 65.2% | |

| Yes | 61 | 34.5% | 4 | 40.0% | 65 | 34.8% | 0.741 |

| SSA | |||||||

| No | 164 | 92.6% | 9 | 90.0% | 173 | 92.5% | |

| Yes | 13 | 7.3% | 1 | 10.0% | 14 | 7.5% | 0.550 |

| Proximal AA with HGD | |||||||

| No | 106 | 59.9% | 2 | 20.0% | 108 | 57.8% | |

| Yes | 71 | 40.1% | 8 | 80.0% | 79 | 42.2% | 0.019 |

| Polyp with HGD and >1cm | |||||||

| No | 45 | 25.4% | 4 | 40.0% | 49 | 26.2% | |

| Yes | 132 | 74.6% | 6 | 60.0% | 138 | 73.8% | 0.292 |

AA: advanced adenoma; CRC: colorectal cancer; HGD: high grade dysplasia; SP: serrated polyp; SSA: sessile serrated adenoma.

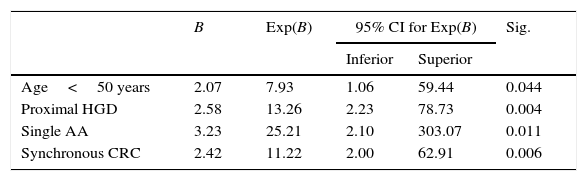

Table 4 shows the results of the multivariate analysis by logistic regression. The model included all the variables that were statistically significant in the univariate study, as well as the presence of synchronous CRC and age (despite not reaching significance in the univariate study, its association with LS is well known). The final model included the variables age <50 years, presence of synchronous CRC, presence of a single AA and proximal location of the polyps with HGD.

Logistic regression with abnormal/normal immunohistochemistry as a dependent variable.

| B | Exp(B) | 95% CI for Exp(B) | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inferior | Superior | ||||

| Age<50 years | 2.07 | 7.93 | 1.06 | 59.44 | 0.044 |

| Proximal HGD | 2.58 | 13.26 | 2.23 | 78.73 | 0.004 |

| Single AA | 3.23 | 25.21 | 2.10 | 303.07 | 0.011 |

| Synchronous CRC | 2.42 | 11.22 | 2.00 | 62.91 | 0.006 |

AA: advanced adenoma; CRC: colorectal cancer; HGD: high-grade dysplasia.

In our population, we observed a prevalence of 5.35% of pathological nuclear expression of DNA repair proteins in newly diagnosed cases of AA with HGD. Although this figure is lower than that described in incidental cases of CRC (12–21%),2,8,9 it is still a high rate, given that we only analysed cases with adenomas with HGD.

This is the first population-based study to assess the prevalence of loss of nuclear expression by IHC in adenomas with HGD. Studies previously conducted on pre-cancerous lesions were limited to patients already diagnosed with LS,11–14 adenomas in general without any selection criteria,16 subgroups of young patients (<40 years),17,18 or the study was carried out without the complete panel of the 4 IHC markers.19 In their review published in 2015, Patel et al.15 suggest performing LS screening on AAs with high pre-test probability (population under 40 or 50 years) in order to improve the early detection and prevention of CRC.

In our study, we observed that early age of onset of the dysplasia (<50 years, coinciding with the cut-off point proposed by the Amsterdam II and revised Bethesda criteria), synchronous presence of CRC and presence of a single AA were significantly associated with abnormal nuclear expression of repair proteins. The appearance of adenomas is known to be relatively rare in patients aged under 50 years, both in the general population and in LS carriers,13,20 although in the case of LS, these progress rapidly and aggressively to dysplasia and cancer. Thus, microadenomas that can appear sporadically at early ages and remain quiescent for years in the general population present accelerated, aggressive malignant change in the case of individuals with LS.11 The fact that this malignant change is faster in patients with LS could explain why we found abnormal IHC in younger patients. Similarly, a single adenoma or synchronous CRC is construed as a risk factor because risk is determined not by the number of lesions that are altered in LS, but by the swiftness of their evolution. A patient who does not present this syndrome could have 1 or 2 quiescent microadenomas for years, but a deficient MMR system could cause these lesions to evolve to HGD and CRC. However, since the genetic profile of these 10 patients with abnormal IHC and the status of the BRAF V600 gene are unknown, we cannot draw firm conclusions, but must consider these findings with caution and await more conclusive studies.

Another risk factor for presenting pathological nuclear IHC in our series was the location of the polyps with HGD in the right colon. These results are consistent with an Indian study conducted in 201116 on adenomas in the general population, studied by IHC, which reported a greater tendency to present pathological results if the polyp was located in the right colon. This is also in line with the scientific evidence available to date, which describes a greater tendency to present CRC in the right colon in patients with LS,11 so it is logical that its precursor lesions also do so.

Despite finding an association between the presence of synchronous CRC and abnormal IHC in adenomas with HGD, this has little relevance in clinical practice, as the test has been shown to be more sensitive in CRCs and will therefore not lead to changes in current recommendations.

Another important finding in our study was the routine performance of IHC for DNA repair proteins in almost 90% of cases with HGD. Although this shows that adherence to this practice was incomplete, it did reach percentages superior to those described previously in other studies on tumour samples, far surpassing the best results obtained by Marquez el al.,2 which were around 76%.

A strong point of our study was its population-based design, which allowed a large number of cases to be recruited.

Among the limitations of our study is the possibility of inter-observer bias in the interpretation of the IHC, despite the expertise of the pathologists. Another limitation is the small number of cases with abnormal IHC, so the results should be interpreted with caution. Finally, the lack of results from genetic and molecular studies (MSI, CIMP status, BRAF V600 mutation) in our cases at present does not allow us to report the diagnostic yield of screening of LS by IHC, nor to distinguish pathological expression of DNA repair proteins due to other causes. In this respect, it would be interesting to conduct new studies focusing on this diagnostic confirmation to determine the yield of the universal LS screening strategy by IHC in cases of adenoma with HGD in routine practice.

ConclusionThe prevalence of pathological nuclear expression of DNA repair proteins in patients with adenomas who present HGD in our series was high (5.35%). These data suggest a possible early LS detection strategy using IHC in certain patients diagnosed with AA with HGD (young people, proximal location of the HGD and/or single AA on the colonoscopy). It would be interesting to develop new studies that would provide more data to confirm the indication to carry out this screening in the cases described.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Basterra M, Gomez M, Mercado MdR, Irisarri R, Amorena E, Arrospide A, et al. Prevalencia de alteración de expresión nuclear de proteínas reparadoras con inmunohistoquímica sobre adenomas con displasia de alto grado y características asociadas a dicho riesgo en un estudio de base poblacional. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:500–507.