Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is highly prevalent in our environment and is associated with highly relevant gastric disease, both benign and malignant. The gold standard for diagnosis is histological confirmation by biopsy. However, there is increasing evidence that optical endoscopic diagnosis could be a fundamental role in avoiding unnecessary biopsies in certain cases. Specifically, the regular distribution of the collecting venules (RAC pattern) seems to have a high negative predictive value (NPV) to rule out infection. This review describes the most outstanding endoscopic findings with the best diagnostic potential for H. pylori infection after an exhaustive search comparing the most relevant studies that have been carried out in Europe and the East.

La infección por Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) es muy prevalente en nuestro medio y se asocia a patología gástrica muy relevante, tanto benigna como maligna. El patrón oro para su diagnóstico sigue siendo, a día de hoy, la confirmación histológica por biopsia. Sin embargo, cada vez hay más evidencia de que el diagnóstico endoscópico óptico podría tener un papel fundamental que permitiría ahorrar biopsias innecesarias en casos determinados. Concretamente, la distribución regular de las vénulas colectoras (patrón RAC) parece tener un alto valor predictivo negativo (VPN) para descartar dicha infección. En la presente revisión se describen los hallazgos endoscópicos más destacados y con mejor potencial diagnóstico para la infección por H. pylori tras una búsqueda exhaustiva comparando los estudios más relevantes que se han llevado a cabo en Europa y Oriente.

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is one of the most common infections in the world, affecting from 10% to over 80% of the population depending on the region, with a prevalence of around 50% in the Spanish population.1H. pylori-induced gastritis is currently considered one of the most important risk factors for gastric and duodenal ulcer disease, gastric cancer (GC) and its precursor lesions (atrophy, metaplasia and dysplasia), and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma.

In symptomatic patients, gastroscopy with biopsies is the preferred test for diagnosing H. pylori infection, as it allows us to characterise the gastric mucosal pattern and pathology examination will identify Gram-negative bacilli resistant to acid pH. Gastroscopy is also a chance to improve GC prevention by identifying premalignant lesions. In recent years, progress has been made in the real-time diagnosis (optical diagnosis) of GC precursor lesions, which are almost always associated with an underlying H. pylori infection. Using techniques such as chromoendoscopy or magnification, the arrangement of the gastric mucosa can be better visualised, thus enabling targeted biopsies in areas of suspected atrophy, intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia. These high-quality gastroscopies require expert endoscopists and a significantly longer mean examination time than other types of gastroscopy.

The diagnosis of H. pylori infection based on the changes in the mucosal arrangement observed during gastroscopy has a series of advantages, and has been the subject of numerous studies in Eastern countries. On the one hand, identifying endoscopic signs which determine that the mucosa is normal makes it possible to rule out patients who do not have H. pylori infection and are therefore at low risk of developing GC precursor lesions. In these patients, the endoscopic technique could be adapted in situ, not only reducing the total examination time but also avoiding the need for biopsies, with the reduction of additional costs. On the other, findings of suspicious mucosal changes suggestive of H. pylori infection would justify the use of advanced imaging techniques, along with application of comprehensive protocols for taking photographs and targeted and random biopsies.

The aim of this review is to describe the endoscopic signs related to H. pylori infection, so first of all we have to know what normal gastric mucosa looks like.

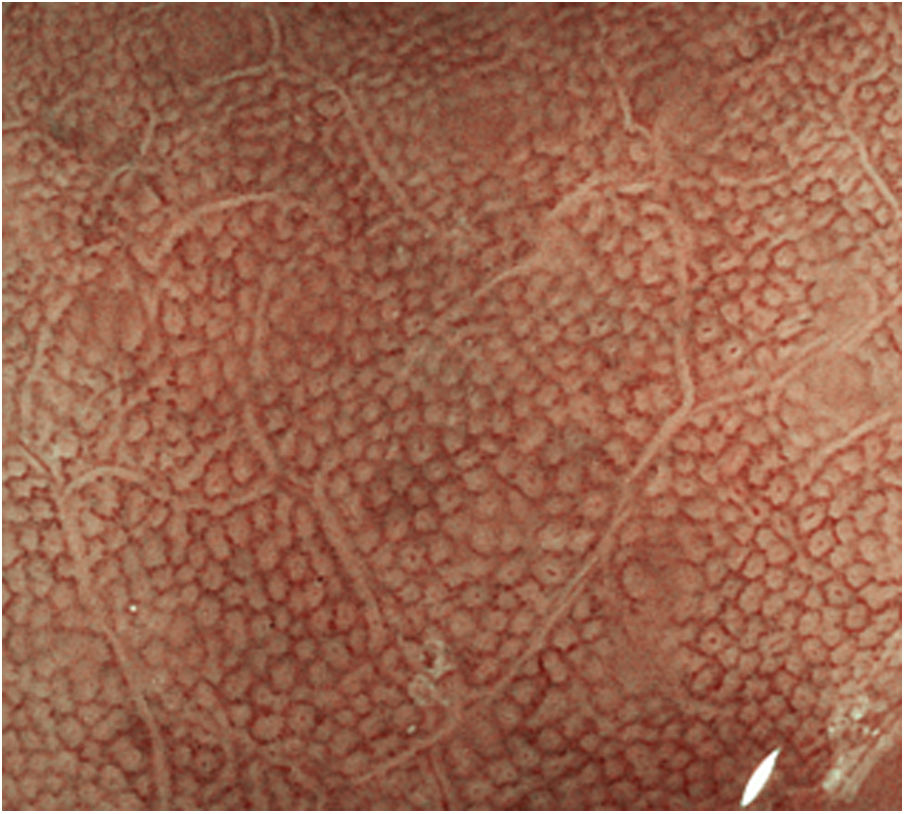

Endoscopic appearance of normal gastric mucosaNormal gastric mucosa is characterised by the presence of fundic or pyloric glands, depending on the more proximal or distal location respectively, and by gastric collecting venules.2 In the gastric body, the glands are arranged vertically and the crypt openings in the surface epithelium are round and surrounded by the marginal epithelium and subepithelial capillaries. The vertical arrangement makes it easier to interpret the endoscopic image under magnification (Fig. 1). In the antrum, the glands are tilted so that the subepithelial capillaries can be seen in the centre and the marginal crypt epithelium peripherally, giving a crest-like image.

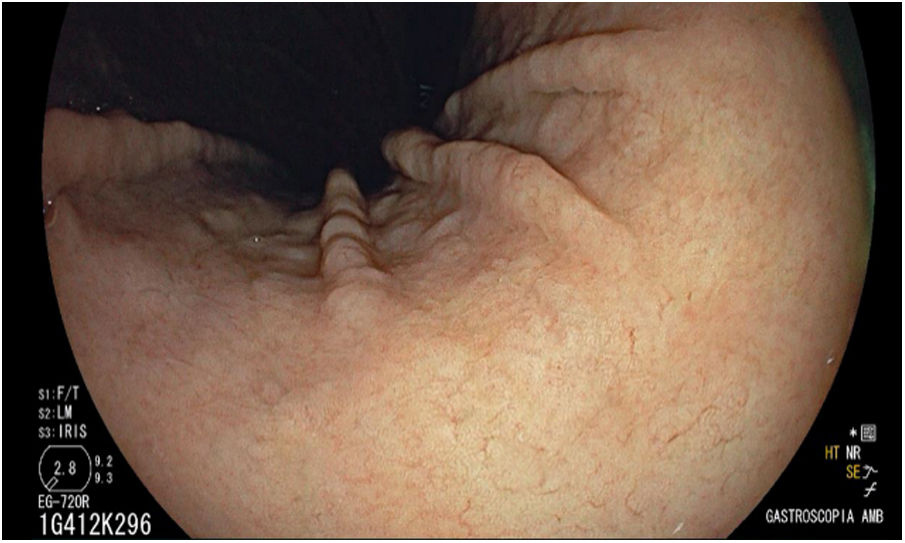

The collecting venules can be observed in the mucosa of the body and fundus, adopting a "starfish" appearance (Fig. 2). The regular arrangement of collecting venules (RAC) has been reported as an indicator of normal mucosa.

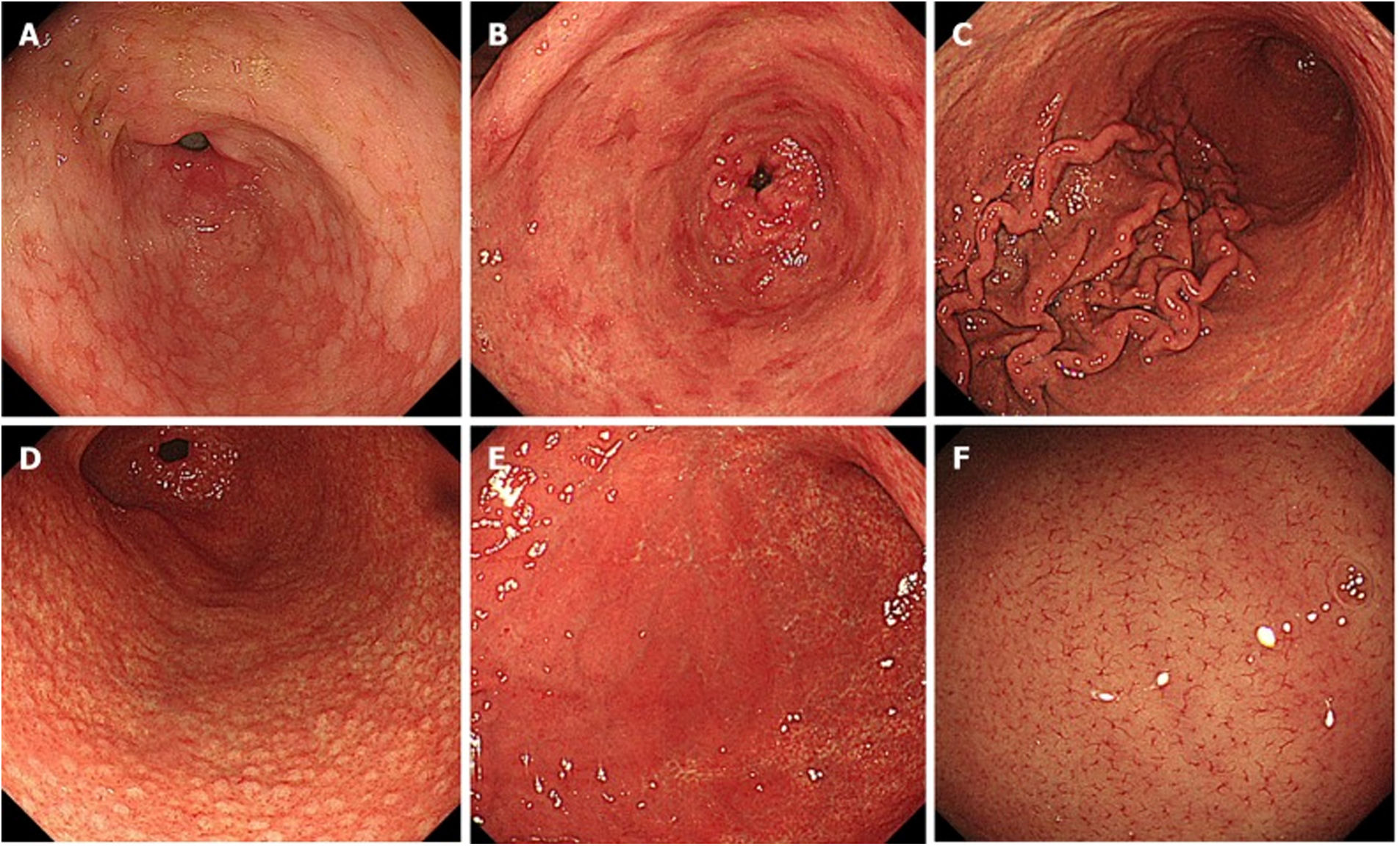

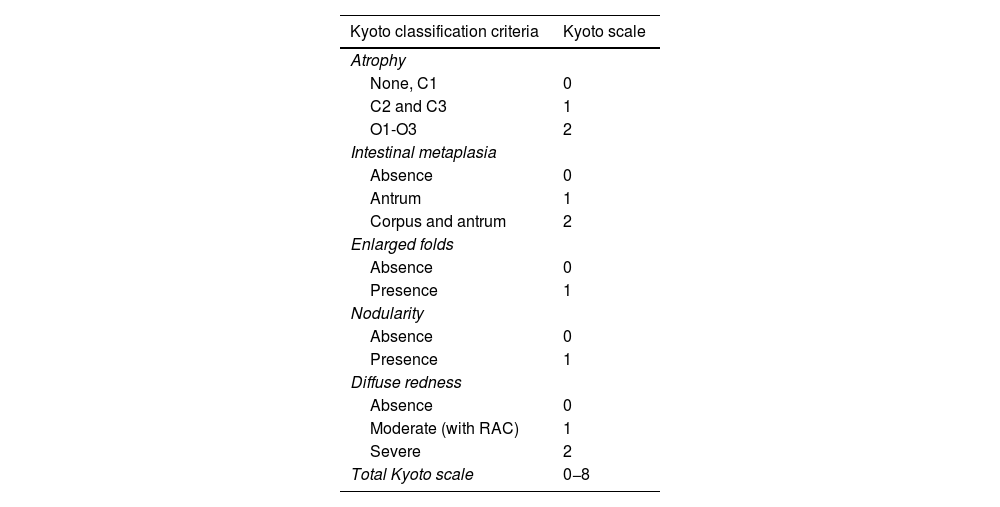

In 2013, the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society compiled a series of endoscopic findings related to GC risk, calling it the Kyoto classification.3 This classification score organises 19 findings related to chronic gastritis, including atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, enlarged folds, nodularity, diffuse redness, RAC, map-like redness, hyperplastic polyps, xanthoma, mucosal swelling, patchy redness, depressed erosion, sticky mucus, haematin, red streak, spotty redness, white and flat elevated lesions, fundic gland polyp and raised erosion (Fig. 3).

Endoscopic findings, Kyoto classification: A) intestinal metaplasia; B) patchy redness; C) enlarged folds; D) nodularity; E) diffuse redness; F) regular arrangement of collecting venules. By kind permission of Toyoshima et al.5

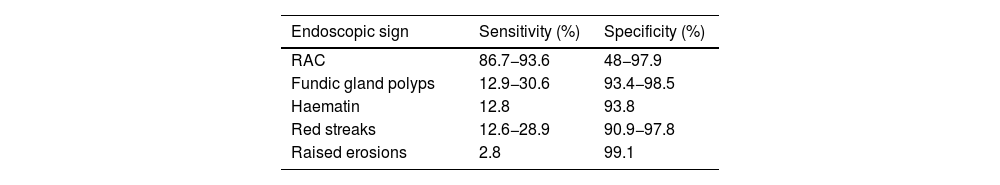

Of all the Kyoto classification criteria, the one with the highest degree of association with the absence of H. pylori infection was the RAC pattern. Diffuse redness was the criterion which best combined sensitivity and specificity for the determination of gastric mucosa with H. pylori infection4 (Table 1).

Sensitivity and specificity of endoscopic signs of the gastric mucosa without infection by H. pylori with white light.

| Endoscopic sign | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| RAC | 86.7−93.6 | 48−97.9 |

| Fundic gland polyps | 12.9−30.6 | 93.4−98.5 |

| Haematin | 12.8 | 93.8 |

| Red streaks | 12.6−28.9 | 90.9−97.8 |

| Raised erosions | 2.8 | 99.1 |

RAC: regular arrangement of collecting venules.

The Kyoto scale published by Toyoshima et al. in 20205 (Table 2) selects the findings which are most specific and sensitive for determining risk of GC (atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, enlarged folds and nodularity) and H. pylori infection (diffuse redness and RAC) and assigns them a score. A score of 0 indicates no H. pylori infection, a score of 2 or higher indicates risk of H. pylori infection, and a score of 4 or above could indicate risk of early GC.

Kyoto scale.

| Kyoto classification criteria | Kyoto scale |

|---|---|

| Atrophy | |

| None, C1 | 0 |

| C2 and C3 | 1 |

| O1-O3 | 2 |

| Intestinal metaplasia | |

| Absence | 0 |

| Antrum | 1 |

| Corpus and antrum | 2 |

| Enlarged folds | |

| Absence | 0 |

| Presence | 1 |

| Nodularity | |

| Absence | 0 |

| Presence | 1 |

| Diffuse redness | |

| Absence | 0 |

| Moderate (with RAC) | 1 |

| Severe | 2 |

| Total Kyoto scale | 0−8 |

RAC: regular arrangement of collecting venules.

The scores between 0 and 2 obtained in the 5 findings described in the gastroscopy are added for the final score.

These results have been confirmed by Yoshii et al.6 These authors found that RAC was the endoscopic sign which best correlated with the absence of H. pylori with an odds ratio (OR) of 32. In the case of patients with H. pylori infection, the most significant endoscopic sign was diffuse redness (OR = 26.8). The overall diagnostic accuracy rate for H. pylori gastritis on the Kyoto scale was 82.9%.

Regular arrangement of collecting venulesRAC was a finding in the mucosa of the gastric body determined for the first time in 2002 in Japan by Yagi et al.,7 the ideal location for detection being at the lower part of the lesser curvature of the stomach (Fig. 4).

To date, most published studies have evaluated the RAC pattern in different combinations with other Kyoto classification criteria. Until 2019, only four studies had examined the role of RAC as a single finding and three of them had been conducted in Japan with magnification endoscopy.8–11 All of them confirmed the utility of the RAC pattern for ruling out H. pylori infection, with an efficacy of 95.5% and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 99%. In 2019 Garcés-Duran et al.12 carried out one of the first studies in a European cohort of 140 patients without using magnification and obtained an NPV of RAC of 100% for ruling out H. pylori infection after very simple training. Since then, these findings have been confirmed in various studies conducted in China, Brazil, Germany and Great Britain.13–15 No significant differences have been observed in the RAC pattern according to gender. Regarding age, studies have been carried out mainly in the adult population with wide age ranges, from adolescence to older adults.8,16 Alaboudy et al.16 found significant differences between those over and under 60 years of age, the sensitivity of the RAC being lower in those patients over 60 (80% vs 94.7%; p ≤ 0.001).

Like Alaboudy et al., our group12 found a significantly reduced RAC and more endoscopic findings (erosive lesions or signs of atrophy) in patients over 50. However, our specificity and precision values for the RAC were lower compared to other studies,17 being particularly low in patients over 60. As the prevalence of H. pylori infection was similar between the different age groups, this would indicate that the disappearance or irregularity of the arrangement of the collecting venules may also be associated with other age-related inflammatory factors in the gastric mucosa. Thus, as previously mentioned, the efficacy of the endoscopic diagnosis of H. pylori through the arrangement of gastric collecting venules seems to be affected by the age of the patient.16,18 However, these differences have not been confirmed in other studies.14,19

Excellent results of the RAC pattern were also confirmed in the paediatric population, with sensitivities greater than 95%.20

Role of proton pump inhibitors in assessing the regular arrangement of collecting venulesIn all the published studies on the endoscopic diagnosis of H. pylori by RAC, histology was used as the "gold standard" for diagnosing H. pylori, very often in combination with other diagnostic methods such as the urease test,14,18,20 culture,7,21,22 serology,3,20,24 breath test3,14 and even immunohistochemistry (IHC).16 The effect of taking proton pump inhibitors (PPI) on the results of these tests is well known: false negatives can occur due to decreased density and proximal migration of H. pylori. For that reason, most studies excluded patients on active treatment with PPI. Only three of these studies included patients treated with PPI. The first of these was the study by Nakayama et al.,18 in which the diagnostic approach in these patients was not specified in the methodology to avoid the risk of false negatives for H. pylori. The second was the study by Alaboudy et al.16 in which systematic IHC staining was performed as a complementary diagnostic method for the detection of H. pylori in patients with positive serology for H. pylori. However, neither of these analysed the possible differences in the significance of the RAC according to whether or not they took PPI. Garcés-Durán et al.23 showed that the detection of RAC has a similar prevalence in patients on treatment with PPI and in the general population. However, in these patients the diagnostic yield of H. pylori infection by histological study is significantly lower, so assessing the RAC pattern may play a fundamental role in the diagnostic approach here.

To date, there have been no studies assessing the effects of gastric irritant drugs on the RAC pattern.

Reproducibility of the regular arrangement of collecting venules patternThree studies carried out in Eastern countries assessed the intra- and inter-observer variability of the RAC pattern, all with good results. In the first,15 two endoscopists using magnification were compared, and high values of both intra- and interobserver agreement were obtained (kappa 0.848 and 0.737 respectively). Watanabe et al.19 found good diagnostic efficacy of RAC both in inexperienced and more experienced endoscopists, with an overall diagnostic yield of 88.9% for those not infected with H. pylori. Although the interobserver agreement rate was lower in the less experienced (kappa = 0.46), a clear improvement was found in the reassessment after two years of training (kappa > 0.6). Lastly, Cho et al.24 in Korea confirmed the excellent intra- and interobserver repeatability using high-definition endoscopy (kappa = 0.87 and 0.89 respectively).

Garcés-Durán et al.23 assessed intra- and interobserver agreement in a western country (Spain). This study included 174 patients and 85 (48.9%) were taking PPI. Kappa values for interobserver and intraobserver agreement were substantial (0.786) and excellent (0.906) respectively. All patients were free of H. pylori infection, with a sensitivity and negative predictive value of 100%, regardless of taking PPI.

Finally, the application of artificial intelligence in the endoscopic diagnosis of H. pylori may improve interobserver agreement in addition to reducing examination time. This is demonstrated by a study conducted in Japan which included 222 patients and compared gastroscopy with white light to blue laser imaging (BLI) and linked colour imaging (LCI). The area under the curve in the diagnosis of H. pylori was 0.66 for white light versus 0.96 and 0.95 for BLI and LCI respectively (p < 0.01).25

ConclusionsWe consider endoscopic assessment of the RAC pattern to be an easy and repeatable method for in vivo diagnosis of H. pylori in Western practice. In addition to improving the quality of gastroscopy, detection of an RAC pattern would avoid the need to carry out other diagnostic tests for H. pylori, transforming the examination time, the use of advanced imaging techniques to search for associated lesions, and the requirement for random systematic biopsies for cases with suspected infection. More studies are needed to assess the validity of RAC in patients on treatment with PPI and drugs with gastric irritant potential, such as anti-platelet and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

To the Generalitat de Catalunya [Catalan Autonomous Government] Centres de Recerca de Catalunya (CERCA) [Catalan Research Centers] programme.

![Normal pattern of the mucosa of the gastric body with endoscopy without magnification (Fujifilm "blue laser imaging" [BLI]) observing the glands which are arranged vertically and the openings of the rounded crypts. Normal pattern of the mucosa of the gastric body with endoscopy without magnification (Fujifilm "blue laser imaging" [BLI]) observing the glands which are arranged vertically and the openings of the rounded crypts.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/24443824/0000004600000006/v2_202311101547/S2444382423000913/v2_202311101547/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)