The gut-brain axis describes a complex bidirectional association between neurological and gastrointestinal (GI) disorders. In patients with migraine, GI comorbidities are common. We aimed to evaluate the presence of migraine among patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) according to Migraine Screen-Questionnaire (MS-Q) and describe the headache characteristics compared to a control group. Additionally, we explored the relationship between migraine and IBD severities.

MethodsWe performed a cross-sectional study through an online survey including patients from the IBD Unit at our tertiary hospital. Clinical and demographic variables were collected. MS-Q was used for migraine evaluation. Headache disability scale HIT-6, anxiety-depression scale HADS, sleep scale ISI, and activity scale Harvey–Bradshaw and Partial Mayo scores were also included.

ResultsWe evaluated 66 IBD patients and 47 controls. Among IBD patients, 28/66 (42%) were women, mean age 42 years and 23/66 (34.84%) had ulcerative colitis. MS-Q was positive in 13/49 (26.5%) of IBD patients and 4/31 (12.91%) controls (p=0.172). Among IBD patients, headache was unilateral in 5/13 (38%) and throbbing in 10/13 (77%). Migraine was associated with female sex (p=0.006), lower height (p=0.003) and weight (p=0.002), anti-TNF treatment (p=0.035). We did not find any association between HIT-6 and IBD activity scales scores.

ConclusionsMigraine presence according to MS-Q could be higher in patients with IBD than controls. We recommend migraine screening in these patients, especially in female patients with lower height and weight and anti-TNF treatment.

El eje intestino-cerebro describe una asociación bidireccional compleja entre las enfermedades neurológicas y gastrointestinales (GI). Las comorbilidades GI son frecuentes en la migraña. Nuestro objetivo fue evaluar la presencia de migraña en pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII) y describir las características de la cefalea. Además, analizamos la relación entre la gravedad de la migraña y la EII.

MétodosEstudio transversal a través de encuesta electrónica en pacientes con EII de un hospital terciario. Se recogieron variables clínicas y demográficas. Se usó MS-Q para presencia de migraña. Se incluyeron escala de discapacidad de cefalea HIT-6, ansiedad-depresión HADS, sueño ISI y actividad de EII Harvey-Bradshaw y Partial Mayo.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 66EII y 47controles. Entre los EII, 28/66 (42%) eran mujeres, con una edad media de 42años, y 23/66 (34,84%) tenían colitis ulcerosa. El MS-Q fue positivo en 13/49 (26,5%) de EII y en 4/31 (12,91%) controles (p=0,172). Entre los pacientes con EII, la cefalea fue unilateral en 5/13 (38%) y pulsátil en 10/13 (77%). El sexo femenino (p=0.006), la altura (p=0,003) y el peso más bajos (p=0,002) y el tratamiento con anti-TNF (p=0,035) se relacionaron con la probabilidad de migraña. No encontramos asociación entre el HIT-6 y las escalas de actividad de EII.

ConclusionesLa presencia de migraña de acuerdo al MS-Q podría ser más alta en los pacientes con EII que en controles. Recomendamos realizar un cribado de migraña en estos pacientes, especialmente en mujeres de menor peso y altura y tratamiento anti-TNF.

Migraine is considered a highly disabling disorder, with a 7th position in terms of years lived with disability worldwide. This problem becomes even more significant when various comorbidities, such as autoimmune, gastrointestinal (GI) and psychiatric diseases are present. However, its pathophysiological mechanisms are not fully known, and inflammation, pain mediators and neurotransmitters are under investigation.

In the recent years, more attention is being paid to its comorbidities.1 Among them, GI comorbidities, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), celiac disease or irritable bowel syndrome, are frequent in patients with migraine.2 Furthermore, the GI system has long been implicated in migraine, as it is well known that some GI symptoms (nausea, vomiting and gastroparesis) constitute classical hallmarks of migraine.

This association had formerly been considered casual due to the high prevalence of both migraine and GI disorders in the general population, but recent research argues about a complex bidirectional link between migraine and GI, often referred to as gut-brain axis. The gut-brain axis could be defined as a bidirectional pathway between the central nervous system, GI tract and microbiota, mediated by products generated by bacteria that act at the systemic level, as well as by endocrine and neuronal mechanisms.3 According to this relationship, already described in multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, brain regulates movements and functions of the GI tract and a number of brain functions, such as cognition, behavior and nociception are believed to be under the influence of the gut system.3

Whether GI diseases and migraine are really connected of if GI diseases could somehow cause or aggravate migraine is still unknown. It seems mandatory to study the prevalence of migraine in patients with GI disorders and to explore whether headache disability in these patients is related to the activity of the GI disorder.4 Indeed, recent research has shown that a proper management of the GI disorder might improve the severity of the headache.5

In the present study, we aimed to: (1) assess the presence of migraine defined as a positive result in the Migraine Screen-Questionnaire (MS-Q) in a cohort of patients with IBD compared to a control group, (2) define headache characteristics in patients with a positive MS-Q, and (3) explore whether there is an association between the characteristics and activity of the headache and those of the IBD.

MethodsStudy population and data collectionWe conducted an observational study with a series of consecutive patients with IBD consulting at the Gastroenterology Unit of our center and sex-matched controls selected among patient's partners. The study was conducted according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.6 The study period encompassed January 2021 to April 2021. Recruitment followed a non-probabilistic convenience sampling method, and every patient with IBD consulting at the Gastroenterology Unit was assessed for eligibility. All participants who fulfilled inclusion criteria were offered to participate, and they were contacted via email to complete an informed consent and the online survey.

Eligibility criteriaThe study population were patients with IBD (UC or CD) and controls without IBD.

The inclusion criteria for patients were: (1) patients over 18 years old; (2) diagnosis of UC or CD assessed by a specialist in IBD; (3) ability to access the online survey. The exclusion criteria were: (1) impossibility to fulfill the online survey; (2) prior history of severe headache trauma; (3) prior history of brain tumor; (4) prior history of cerebral artery dissection; (5) lumbar puncture in the previous three years; (6) prior history of neck surgery; (7) patients with other concomitant abdominal pathology (such as dyspepsia or celiac disease); (8) alcohol abuse; (9) COVID-19 infection. Inclusion criteria for the control group were: (1) consent to participate; (2) matched-sex controls, not genetically related; (3) age-matched controls within a range of 5 years of age compared to patients. Exclusion criteria in the control group were (1) IBD diagnosis and (2) same exclusion criteria than patients.

Variables included in the studyA complete medical history was obtained from each patient during an in-person clinical interview, done by a specialist in IBD. Information regarding headache characteristics and scales was collected through the self-reported online survey. The demographic and clinical variables included in the study were sex (male/female), age (years), weight (kg), height (cm). In the online survey subjects were asked if they experienced headaches; those who reported five or more headaches in their lives completed the Migraine Screen-Questionnaire (MS-Q). The MS-Q is a validated tool with adequate validity and reliability as screening tool for application to clinical practice and research in migraine patients.7,8 MS-Q is considered positive with scores ≥4. Other collected variables related with headache were age of headache onset (years), first-degree family history of migraine, pain characteristics (unilateral, throbbing, allodynia), typical aura symptoms, trigeminal-autonomic symptoms, evaluation by a doctor (neurologist or primary care physician), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and triptan use, chronic pain (over 15 days per month) and preventive headache treatment. Moreover, we included Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) scale9 to assess the degree of headache-related disability, divided in four categories (1) little/no impact [0,49]; (2) some impact [49,55] (3) substantial impact [55,59]; (4) very severe impact [59,59]; Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), positive over 15 points,10,11 to assess the prevalence of anxiety disorders and Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) scale positive [10,30]12 to assess the prevalence of sleep disorders. Variables related with IBD included age of onset of IBD, type of IBD (UC or CD), Harvey-Bradshaw activity index (IBD),13,14 Partial Mayo score to evaluate UC activity,15 extraintestinal manifestations, inflammatory parameters (C reactive protein/calprotectin), and current treatment with anti-TNF treatment (infliximab or adalimumab).

Study endpointsThe primary endpoint was the prevalence of migraine according to the MS-Q questionnaire in patients with IBD (EC or UC). Secondary endpoints included the headache characteristics and scale scores in patients with IBD and a positive MS-Q; migraine prevalence comparison between IBD and age-matched control group; analysis of the possible association between clinical headache characteristics in IBD and controls; and description of the variables associated with a positive MS-Q in patients with IBD, as well as the potential association between HIT-6 and IBD activity.

Statistical analysisWe present absolute and relative frequencies for the qualitative variables, and central tendency and dispersion measures for the quantitative variables and 95% confidence intervals. Continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviations (SD) or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) if the Gaussian distribution was not normal, determined by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. If the data did not meet the normality assumptions for the analysis, non-parametric statistical methods were used. Chi square or Fisher test were used to compare categorical variables and Mann–Whitney for continuous variables. The correlation between variables were calculated using Pearson or Spearman. A p<0.05% was considered a statistically significant difference and was bilateral. We assessed the prevalence of migraine measured by the MS-Q questionnaire in patients with IBD and compared it with the prevalence of migraine in the control group. A description of the characteristics of headache associated with IBD is also included. Association studies of the clinical and demographic variables associated with headache in IBD and in the control group were also carried out. An exploratory multivariate logistic stepwise regression model including statistically significant clinical-demographic variables (p<0.05) in the univariate model was obtained. Missing data are indicated in the tables. The statistical analyses were performed using the statistical package SPSS for Windows and R studio.

Ethics approval and consent to participateWritten informed consent was obtained from all patients participating in the current study. Approval by ethics committee of the Hospital Universitario de La Princesa (PI: 4310) was obtained. The study was done according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

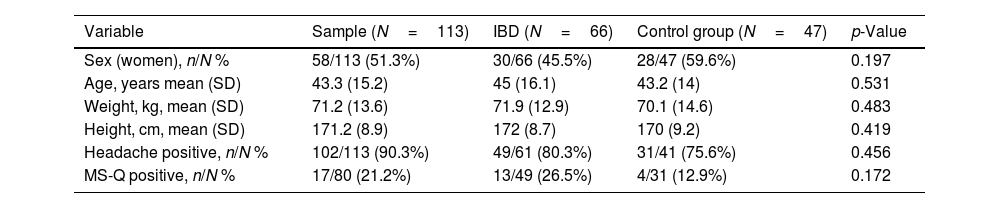

ResultsDuring the study period, 162 participants, 81 patients and 81 controls, fulfilled eligibility criteria. Among those who agreed to participate, 113 (70%) completed the online survey, 66 patients (58%) and 47 sex and aged-matched controls (42%). Clinical characteristics of the sample are included in Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the sample included in the study.

| Variable | Sample (N=113) | IBD (N=66) | Control group (N=47) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (women), n/N % | 58/113 (51.3%) | 30/66 (45.5%) | 28/47 (59.6%) | 0.197 |

| Age, years mean (SD) | 43.3 (15.2) | 45 (16.1) | 43.2 (14) | 0.531 |

| Weight, kg, mean (SD) | 71.2 (13.6) | 71.9 (12.9) | 70.1 (14.6) | 0.483 |

| Height, cm, mean (SD) | 171.2 (8.9) | 172 (8.7) | 170 (9.2) | 0.419 |

| Headache positive, n/N % | 102/113 (90.3%) | 49/61 (80.3%) | 31/41 (75.6%) | 0.456 |

| MS-Q positive, n/N % | 17/80 (21.2%) | 13/49 (26.5%) | 4/31 (12.9%) | 0.172 |

IBD: inflammatory bowel disease. SD: standard deviation. MS-Q: Migraine Screen-Questionnaire.

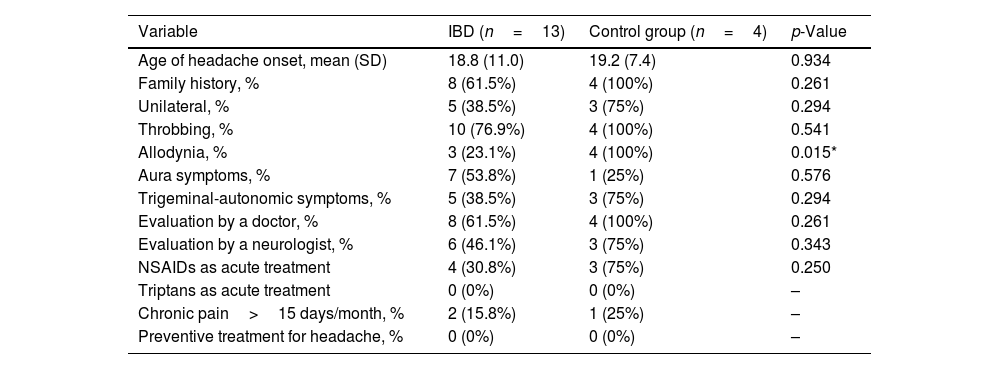

Regarding the primary endpoint of the study, among all the 162 (100%) participants, 80 (49.4%) experienced headache at least five times in their lives and 17 (10.5%) were MS-Q positive. The prevalence of migraine according to MS-Q in patients with IBD was 13/49 (26.5%), with a prevalence of 4/49 (8.2%) among UC and 9/49 (18.3%) in Crohn's disease. Regarding secondary endpoints the prevalence of migraine according to MS-Q was higher in patients with IBD 13/49 (26.5%) than in the control group 4/31 (12.9%), although it did not achieve statistically significant differences (p=0.172) (Table 1). The prevalence of migraine according to MS-Q in patients with UC and CD was also calculated and compared to the control group, with a similar trend of a higher percentage in IBD no achieving statistical significance. Among patients with IBD and positive MS-Q headache was unilateral in 5/13 (38.5%) and throbbing in 10/13 (76.9%). Chronic pain occurred in 2/13 (15.4%) patients, 8/13 (61.5%) had consulted with a physician, 6/8 (75%) with a neurologist and 2/8 (25%) with their primary care physician. NSAIDs as acute treatment were used by 4/13 (30.8%) patients. However, NSAIDs and triptan use was finally not included in further statistical analyses due to lack of homogeneity in type of drug and dosage. The main self-reported headache characteristics in patients with IBD and in the control group are included in Table 2.

Self-reported headache variables among patients with inflammatory bowel disease and control group among patients with a diagnosis of migraine according to the Migraine Screen-Questionnaire (MS-Q).

| Variable | IBD (n=13) | Control group (n=4) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of headache onset, mean (SD) | 18.8 (11.0) | 19.2 (7.4) | 0.934 |

| Family history, % | 8 (61.5%) | 4 (100%) | 0.261 |

| Unilateral, % | 5 (38.5%) | 3 (75%) | 0.294 |

| Throbbing, % | 10 (76.9%) | 4 (100%) | 0.541 |

| Allodynia, % | 3 (23.1%) | 4 (100%) | 0.015* |

| Aura symptoms, % | 7 (53.8%) | 1 (25%) | 0.576 |

| Trigeminal-autonomic symptoms, % | 5 (38.5%) | 3 (75%) | 0.294 |

| Evaluation by a doctor, % | 8 (61.5%) | 4 (100%) | 0.261 |

| Evaluation by a neurologist, % | 6 (46.1%) | 3 (75%) | 0.343 |

| NSAIDs as acute treatment | 4 (30.8%) | 3 (75%) | 0.250 |

| Triptans as acute treatment | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | – |

| Chronic pain>15 days/month, % | 2 (15.8%) | 1 (25%) | – |

| Preventive treatment for headache, % | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | – |

NSAIDs: non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs; –: no statistical analysis can be performed; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease.

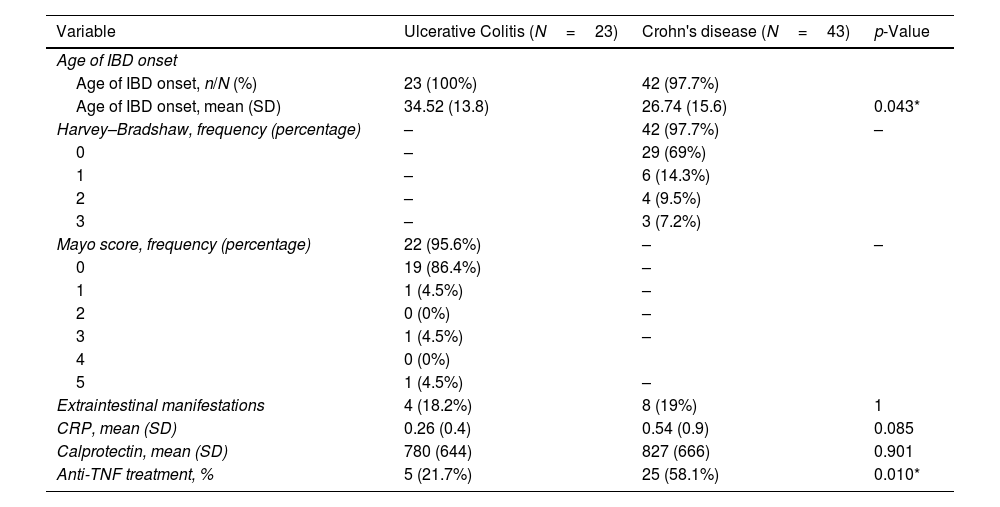

Among patients with IBD, there were 23 patients with UC and 43 patients with CD, 28/66 (42%) were women, mean age 42 (SD: 14) years. Harvey–Bradshaw activity index was ≤4 in 42/43 patients with CD (97.7%) and Partial Mayo score was ≤2 in 22/23 (95.6%) of patients. The main clinical characteristics and activity scale scores are included in Table 3. Patients with a diagnosis of CD had an earlier onset as compared to UC and used anti-TNF treatment more than patients with UC. There were no differences among groups regarding extraintestinal manifestations, CRP mean value or calprotectin.

Characteristics and severity scale score in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

| Variable | Ulcerative Colitis (N=23) | Crohn's disease (N=43) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of IBD onset | |||

| Age of IBD onset, n/N (%) | 23 (100%) | 42 (97.7%) | |

| Age of IBD onset, mean (SD) | 34.52 (13.8) | 26.74 (15.6) | 0.043* |

| Harvey–Bradshaw, frequency (percentage) | – | 42 (97.7%) | – |

| 0 | – | 29 (69%) | |

| 1 | – | 6 (14.3%) | |

| 2 | – | 4 (9.5%) | |

| 3 | – | 3 (7.2%) | |

| Mayo score, frequency (percentage) | 22 (95.6%) | – | – |

| 0 | 19 (86.4%) | – | |

| 1 | 1 (4.5%) | – | |

| 2 | 0 (0%) | – | |

| 3 | 1 (4.5%) | – | |

| 4 | 0 (0%) | ||

| 5 | 1 (4.5%) | – | |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | 4 (18.2%) | 8 (19%) | 1 |

| CRP, mean (SD) | 0.26 (0.4) | 0.54 (0.9) | 0.085 |

| Calprotectin, mean (SD) | 780 (644) | 827 (666) | 0.901 |

| Anti-TNF treatment, % | 5 (21.7%) | 25 (58.1%) | 0.010* |

IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; SD: standard deviation; CRP: C reactive protein; anti-TNF: anti-tumor necrosis factor.

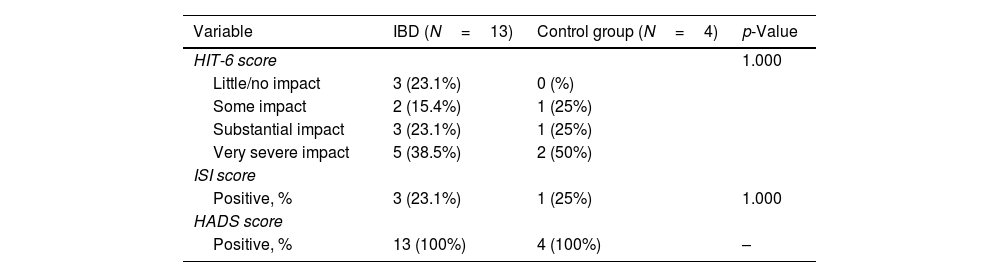

We collected self-reported headache variables among patients with a migraine diagnosis according to MS-Q in patients with UC, CD and in control group. Allodynia was absent in patients with UC and present in CD and in the control group (p=0.016). There were no differences regarding age of headache onset, family history of migraine, prior evaluation by a physician or migraine treatment. None of the patients nor controls used triptans and none of the patients that fulfilled criteria for chronic migraine were on preventive treatment (Table 2). Regarding scale scores, HIT-6 categories, positive ISI score and positive HADS score had a similar distribution between patients with IBD and controls (Table 4).

Headache scale scores among patients with ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease and control group with a diagnosis of migraine according to the Migraine Screen-Questionnaire (MS-Q).

| Variable | IBD (N=13) | Control group (N=4) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIT-6 score | 1.000 | ||

| Little/no impact | 3 (23.1%) | 0 (%) | |

| Some impact | 2 (15.4%) | 1 (25%) | |

| Substantial impact | 3 (23.1%) | 1 (25%) | |

| Very severe impact | 5 (38.5%) | 2 (50%) | |

| ISI score | |||

| Positive, % | 3 (23.1%) | 1 (25%) | 1.000 |

| HADS score | |||

| Positive, % | 13 (100%) | 4 (100%) | – |

–: no statistical analysis can be performed; HIT-6: headache impact test; ISI: insomnia severity index; HADS: Hospital Anxiety-Depression Scale.

*p<0.05.

**p<0.01.

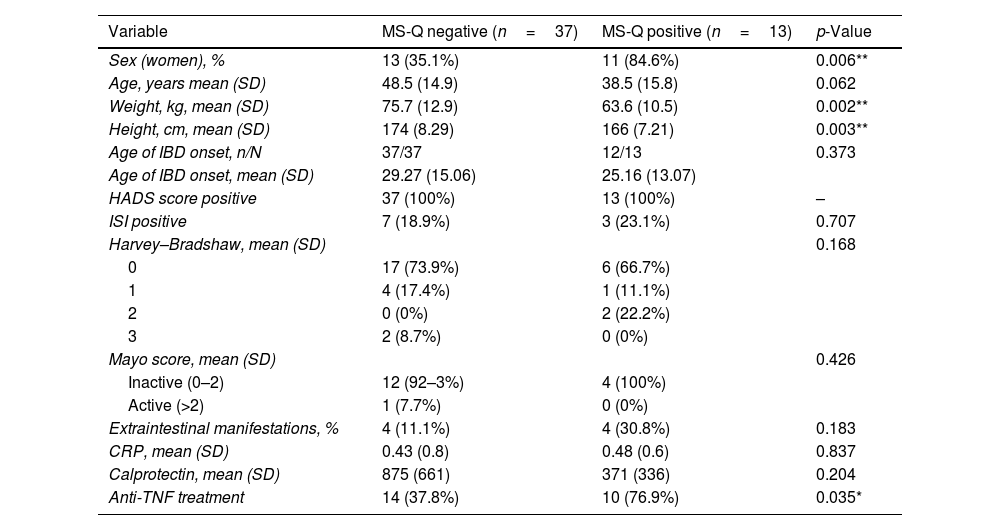

In addition, we explored which variables were associated with a positive MS-Q among patients with IBD. The main results are included in Table 5. We found that a female sex (p=0.006), weight (p=0.002), height (p=0.003) and anti-TNF treatment (p=0.003) were associated with MS-Q positive diagnosis. We did not find association between migraine by MS-Q and other variables. In a multivariate logistic stepwise regression model, it was found that female sex (odds ratio [OR] 0.91; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.84–0.96; p=0.018) and anti-TNF use (OR 5.24; 95% CI 1.48–22.5; p=0.04) were independently associated with a positive MS-Q.

Demographic and clinical variables associated with the Migraine Screen-Questionnaire (MS-Q) in IBD patients.

| Variable | MS-Q negative (n=37) | MS-Q positive (n=13) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (women), % | 13 (35.1%) | 11 (84.6%) | 0.006** |

| Age, years mean (SD) | 48.5 (14.9) | 38.5 (15.8) | 0.062 |

| Weight, kg, mean (SD) | 75.7 (12.9) | 63.6 (10.5) | 0.002** |

| Height, cm, mean (SD) | 174 (8.29) | 166 (7.21) | 0.003** |

| Age of IBD onset, n/N | 37/37 | 12/13 | 0.373 |

| Age of IBD onset, mean (SD) | 29.27 (15.06) | 25.16 (13.07) | |

| HADS score positive | 37 (100%) | 13 (100%) | – |

| ISI positive | 7 (18.9%) | 3 (23.1%) | 0.707 |

| Harvey–Bradshaw, mean (SD) | 0.168 | ||

| 0 | 17 (73.9%) | 6 (66.7%) | |

| 1 | 4 (17.4%) | 1 (11.1%) | |

| 2 | 0 (0%) | 2 (22.2%) | |

| 3 | 2 (8.7%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Mayo score, mean (SD) | 0.426 | ||

| Inactive (0–2) | 12 (92–3%) | 4 (100%) | |

| Active (>2) | 1 (7.7%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Extraintestinal manifestations, % | 4 (11.1%) | 4 (30.8%) | 0.183 |

| CRP, mean (SD) | 0.43 (0.8) | 0.48 (0.6) | 0.837 |

| Calprotectin, mean (SD) | 875 (661) | 371 (336) | 0.204 |

| Anti-TNF treatment | 14 (37.8%) | 10 (76.9%) | 0.035* |

–: no statistical analysis can be performed; ISI: insomnia severity index; HADS: Hospital Anxiety-Depression Scale; CRP: C reactive protein.

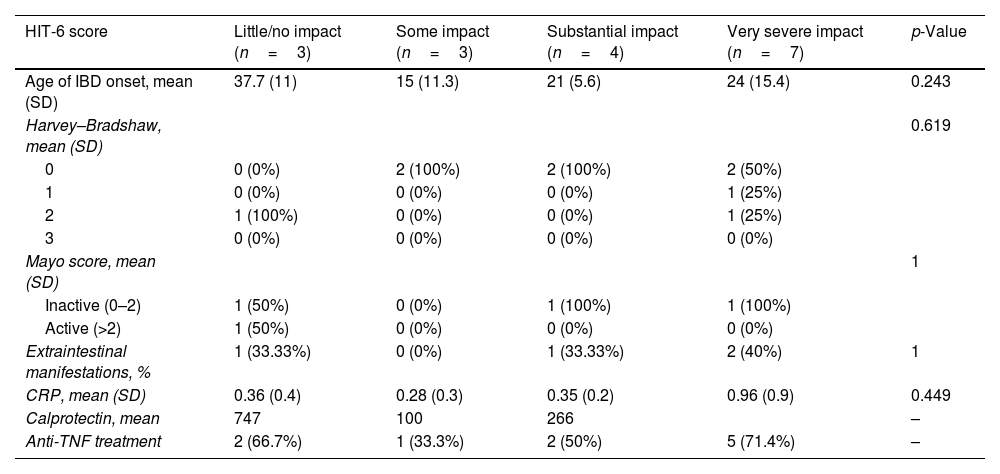

We did not find any statistically significant difference between HIT-6 score and activity scale scores or IBD variables, including Harvey–Bradshaw or Partial Mayo categories, years of IBD, CRP mean values or anti-TNF treatment. The associations are included in Table 6.

Relationship between headache variables and IBD variables among patients with migraine diagnosis according to the Migraine Screen-Questionnaire (MS-Q).

| HIT-6 score | Little/no impact (n=3) | Some impact (n=3) | Substantial impact (n=4) | Very severe impact (n=7) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of IBD onset, mean (SD) | 37.7 (11) | 15 (11.3) | 21 (5.6) | 24 (15.4) | 0.243 |

| Harvey–Bradshaw, mean (SD) | 0.619 | ||||

| 0 | 0 (0%) | 2 (100%) | 2 (100%) | 2 (50%) | |

| 1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (25%) | |

| 2 | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (25%) | |

| 3 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Mayo score, mean (SD) | 1 | ||||

| Inactive (0–2) | 1 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | 1 (100%) | |

| Active (>2) | 1 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Extraintestinal manifestations, % | 1 (33.33%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (33.33%) | 2 (40%) | 1 |

| CRP, mean (SD) | 0.36 (0.4) | 0.28 (0.3) | 0.35 (0.2) | 0.96 (0.9) | 0.449 |

| Calprotectin, mean | 747 | 100 | 266 | – | |

| Anti-TNF treatment | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (50%) | 5 (71.4%) | – |

–: no statistical analysis can be performed.

In this study, we found that the prevalence of migraine according to MS-Q in patients with IBD was 19.7%, in whom some migraine characteristics such as unilateral location and throbbing quality were especially frequent. Moreover, there was a trend toward a higher migraine prevalence in patients with IBD compared to the control group. Among patients with IBD, patients with migraine according to MS-Q were mainly female, had lower weight and height and a higher anti-TNF treatment use. However, in our study, we did not find any association between headache impact measured by HIT-6 scale and IBD activity scales scores.

Regarding the primary endpoint of our study, the prevalence of migraine among patients with IBD, we found that it was higher than the prevalence of the general population which ranges between 6% among men and 15–17% among women.16 Moreover, there is a trend toward a higher prevalence in patients with IBD, either UC or CD, compared to controls, according to the MS-Q test. In our study, these results did not achieve statistically significant differences probably due to the limited sample size.

These results are aligned with previous studies. For example, in a cross-sectional household survey that provides nationally representative estimates of self-reported health information for the civilian, non-institutionalized US population, a higher prevalence of migraine in patients with IBD compared to controls was also described.17 However, to date, few studies have systematically analyzed the prevalence of migraine in IBD, with heterogeneous results.18–20

This possible gut-brain axis relationship has also been reported in patients with celiac disease, who also showed higher prevalence rates, according to a migraine screening tool (ID-migraine).21,22 Ancient Persian physicians already believed in a headache arising from the stomach, the “Gastric Headache”.23 Nowadays, we know that immune, neuroendocrine and metabolic pathways are involved in this complex relationship between headache and GI disorders.2 One of the interesting pathophysiological and underlying mechanisms is disruptions of the serotonergic system, as both IBD and migraine have been related to low serotonin levels. Moreover, gut permeability and tract microbiota might also play an important role in this condition.4,19

Inflammatory diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, have been reported to increase the risk of migraine.24 Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD) are systemic, chronic inflammatory conditions that predominately affect the GI tract, but in which numerous extra-intestinal manifestations (articular, cutaneous, and ocular) are common. Despite not being one of the clinical hallmarks of IBD, headache has been found to be the most common neurological complaint among patients with IBD25 and frequent in celiac disease, which may imply a general migraine-generating inflammatory mechanism and highlights the probable role of the gut-brain axis in the co-occurrence of these pathologies.21

The liberation of pro-inflammatory cytokines into the bloodstream in patients with IBD could be a way to favor migraine. However, in previous studies, migraine has failed to be related to IBD clinical activity.18 Some authors have argued that a slight inflammatory activity could be sufficient to maintain migraine activity in patients with IBD, even in the absence of other clinical of intestinal manifestations.20

Although further studies are needed to confirm whether migraine should be classified as IBD extra-intestinal manifestations, such association has been reported by other authors.26 However, to date, systematic screening is not recommended to date, as migraine is not considered as an extra-intestinal manifestation so far, although this co-occurrent symptom seems to be even more frequent than joint involvement, which is traditionally considered to be the most frequent extra-intestinal manifestation.24

In this sense, we believe that our results highlight the importance of migraine screening among patients with IBD and support the connection between migraine and inflammatory conditions which requires further study. For migraine screening in this population, we proposed the MS-Q as a rapid and easy self-administrated migraine screening tool with appropriate sensitivity and specificity.

Regarding the headache related variables among patients with IBD and positive MS-Q, it is worth mentioning that none of the patients with chronic migraine (over 15 days/month) were on preventive treatment and some of these patients had never contacted a physician to be evaluated for their headaches. Furthermore, none of the patients with a diagnosis of migraine according to MS-Q were using triptans and few NSAIDs. In patients with both migraine and GI disorders, the absorption of migraine medications may be decreased due to GI disorders.27

Underdiagnosis in migraine has been argued in previous studies, which has been related to underconsultation and diagnosis delay. Many patients with migraine suffered their headaches since childhood or teenagers and have a positive familiar history; a possible normalization of pain in this context and self-stigma could explain a lack of awareness of the disease. In patients with IBD this rate of consultation could be even lower, as patients might gibe lower priority to migraine than to their IBD. NSAIDs have been related to IBD activity, which could explain their avoidance in this population. Moreover, triptans are poorly prescribed in Primary Care due to an initial fear to cardiovascular effects and adherence to prophylactic treatment in patients with migraine could be as low as 30% at 6 months mainly due to adverse effects. In this sense, we believe that our results in the IBD population with a positive MS-Q do not differ from usual results in the migraine population.

In addition, we explored whether there was an association between clinical variables and a positive MS-Q among patients with IBD. We found that a female sex, lower height and weight, and use of anti-TNF treatment were associated with a positive MS-Q. The higher prevalence of women among MS-Q could be explained by the higher prevalence of migraine among women at a rate of 3:1,28 and higher prevalence of women among IBD.29 Moreover, we found that lower weight and height were associated with migraine in patients with IBD. Migraine may be improved by dietary approaches, such as weight loss dietary plans for overweight and obese patients, that may have an additional effect on gut microbiota and gut-brain axis. However, low height could also be related with malnutrition or celiac disease which could be a potential factor for migraine worsening in patients with IBD.30 In our study, nutritionals parameters such as albumin levels were not included, so that we could not assure whether a lower weight was associated to better nutritional status or not. Use of anti-TNF therapies reflect a moderate-severe disease and the association with a positive MS-Q supports the role of inflammation underlying this gut-brain axis disease.

Finally, we did not find a statistically significant association between HIT-6 score and Harvey–Bradshaw or Partial Mayo scores, years of IBD, CRP mean values or anti-TNF treatment. Prior studies have explored the potential association between disability in IBD scales such as Mayo score or Crohn's disease activity index (CDAI) and HIT-6 with similar results.31 However, it is possible that we need larger studies to address this potential association as the vast majority of the patients included in our study were on remission from their IBD. We believed IBD activity is probably not related to migraine prevalence, but it can impact on migraine severity in terms of frequency and/or intensity.

There are several limitations associated with the present study. Among them, the main one is the limited sample size and we cannot discard a selection bias (patients willing to participate in the study being more probably headache sufferers). Further studies with a larger sample size will improve the detection of differences between CD and UC to assess different disease mechanisms and epidemiological characteristics. Another possible limitation of our study was that migraine was assessed through a screening tool, but was not confirmed by clinical anamnesis. Finally, self-reported variables are subject to recall bias, but online survey was necessary due to the pandemic situation. Nonetheless, we think that our results point out the utility of the easy-to-use migraine screening tool MS-Q to detect migraine among patients with IBD.

In conclusion, our results support the association between migraine and IBD. We found that the presence of migraine could be as high as one out of five patients with IBD according to the MS-Q screening test, and some characteristics, such as unilateral location and throbbing quality, were especially frequent among these patients. Among patients with IBD, female sex, lower weight and height and anti-TNF treatment use were associated with a positive MS-Q. We believe that our results show the necessity of implementing rapid screening questionnaires for assessing migraine in patients with IBD, as it may change the current management of these patients.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestDr. Alicia Gonzalez-Martinez has received education funding from Lilly, Novartis, Roche, TEVA, Abbvie-Allergan, & Daichi.

Dr. Inés Muro García has received speaker honoraria from Bial, Zambon and Lundbeck.

Dr. S. Quintas has received speaker honoraria from Lilly, Bial, UCB, AlterMedica, Eisai and Novartis.

Dr. María Chaparro has served as a speaker, as consultant or has received research or education funding from MSD, Abbvie, Hospira, Pfizer, Takeda, Janssen, Ferring, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Tillotts Pharma, Biogen, Gilead and Lilly.

Dr. Gisbert has served as speaker, consultant, and advisory member for or has received research funding from MSD, Abbvie, Pfizer, Kern Pharma, Biogen, Mylan, Takeda, Janssen, Roche, Sandoz, Celgene/Bristol Myers, Gilead/Galapagos, Lilly, Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Tillotts Pharma, Chiesi, Casen Fleet, Gebro Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Norgine and Vifor Pharma.

Ancor Sanz PhD reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

Dr. María José Casanova has received research or education funding from Pfizer, Takeda, Janssen, MSD, Ferring, Abbvie, Biogen, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Tillotts Pharma, Chiesi and Norgine.

Dr. Cristina Rubín de Célix has received education funding from Norgine, Janssen, Abbvie, Pfizer, Takeda and Ferring.

Dr. José Vivancos has served as speaker, consultant, and advisory member for or has received research funding from MSD, Pfizer, Daychii-Sankyo, Bayer, Sandoz, Bristol Myers Skibb, Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Almirall, Sanofi-Aventis and Ferrer Pharma.

Dr. Ana Beatriz Gago-Veiga has received honoraria from Lilly, Novartis, TEVA, Abbvie-Allergan, Exeltis & Chiesi.