Loss-of-response and adverse events (AE) to biologics have been linked to HLA-DQA1*05 allele. However, the clinical factors or biologic used may influence treatment duration. Our objective was to evaluate the influence of clinical and therapeutic factors, along with HLA, in biological treatment discontinuation.

MethodsA retrospective study of consecutive IBD patients treated with biologics between 2007 and 2011 was performed. Main outcome was treatment discontinuation due to primary non-response (PNR), secondary loss of response (SLR) or AE. HLA-DQA1 genotyping was done in all patients. Regression analyses were used to assess risk factors of treatment discontinuation.

ResultsOne hundred fifty patients (61% male) with 312 biologic treatments were included. 147 (47%) were discontinued with a cumulative probability of 30%, 41% and 56% at 1, 2 and 5 years. The use of infliximab (p=0.006) and articular manifestations (p<0.05) were associated with treatment discontinuation. Considering cause of withdrawal, Ulcerative Colitis (UC) had a higher proportion of PNR (HR=4.99; 95% CI=1.71–14.63; p=0.003), SLR was higher if biologics had been indicated due to disease flare (HR=2.32; 95% CI=1.05–5.09; p=0.037) while AE were greater with infliximab (HR=2.46; 95% CI=1.48–4.08; p<0.001) or spondylitis (HR=2.46; 95% CI=1.78–6.89; p<0.001). According to the biological drug, HLA-DQA1*05 with adalimumab showed more SLR in cases with Crohn's disease (HR=3.49; 95% CI=1.39–8,78; p=0.008) or without concomitant immunomodulator (HR=2.8; 95% CI=1.1–6.93; p=0.026).

ConclusionsHLA-DQ A1*05 was relevant in SLR of IBD patients treated with adalimumab without immunosupression. In patients treated with other biologics, clinical factors were more important for treatment interruption, mainly extensive UC or extraintestinal manifestations and having indicated the biologic for flare.

Estudios previos han observado una asociación entre el HLA-DQA1*05 y la pérdida de respuesta a biológicos y el desarrollo de efectos adversos (EA). Hay factores clínicos y biológicos que podrían influir en la duración del tratamiento. El objetivo del estudio fue evaluar la influencia del HLA, de factores clínicos y terapéuticos en la interrupción del tratamiento biológico.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio retrospectivo de pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII) tratados con biológicos entre 2007 y 2011. Los principales eventos analizados fueron la suspensión del tratamiento por fallo de respuesta primaria (PRP), secundaria (PRS) o EA. Se realizó un tipaje del HLA-DQA1*05 y se evaluaron los factores de riesgo de interrupción del tratamiento mediante un análisis de regresión logística.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 150 pacientes y 312 tratamientos, de los cuales se suspendieron 147 (47%) en el seguimiento. El infliximab (p=0,006) y las manifestaciones articulares (p<0,05) se relacionaron con la interrupción del tratamiento. La colitis ulcerosa (CU) presentó mayor PRP (HR: 4,99; IC 95%: 1,71-14,63; p=0,003), el brote como indicación de tratamiento se asoció a más PRS (HR: 2,32; IC 95%: 1,05-5,09; p=0,037); el uso de infliximab (HR: 2,46; IC 95%: 1,48-4,08; p<0,001) y la espondilitis (HR: 2,46; IC 95%: 1,78-6,89; p<0,001) a la suspensión por EA. El HLA-DQA1*05 fue un factor de riesgo de PRS en los pacientes tratados con adalimumab (ADA) con enfermedad de Crohn (HR: 3,49; IC 95%: 1,39-8,78; p=0,008) o con EII sin inmunosupresor asociado (HR: 2,8; IC 95%: 1,1-6,93; p=0,026).

ConclusionesEl HLA-DQA1*05 se asoció al cese del tratamiento con ADA por PRS en los pacientes con EII sin inmunosupresor asociado. Respecto a otros biológicos, la suspensión se debió más a factores como la CU, las manifestaciones articulares y la indicación para remisión de brote intestinal.

IBD is a chronic disease whose treatment is sometimes complex because there is no established marker to indicate which treatments will work better on each patient. In the past years, studies have been performed to determine response-related factors, with recent interest in genetic predisposition to explain loss of response.1 Development of antiTNF-α antibodies (immunogenicity) has been related to the loss-of-response to antiTNF drugs and to the development of side effects.2–5 Based on this, some authors link response to biologics and tolerance to having the HLA-DQ A1*05 allele, and have therefore proposed determining this allele to decide what to prescribe.2,3,5

Besides genetics, other factors such as the amount of inflammation may influence response to biologic treatment and, therefore, treatment duration. This depends on disease extension,6 flare severity,1 having perianal disease7 or extraintestinal symptoms.1 The type of biologic that is used8 and co-treatments9,10 also play an important role in therapeutic response, as well as side effects that may lead to treatment interruption. Nevertheless, the interaction of genetic, clinical and therapeutic factors on the risk of treatment interruption has not been widely studied, and even less with the most recent biological drugs.

Our hypothesis was that biological treatment discontinuation depends not only on HLA-DQA1*05, but also, and more importantly, on clinical and therapeutic factors in real-life-practice. Our objective was to evaluate the influence of clinical and therapeutic factors, along with HLA, in biological treatment discontinuation.

Materials and methodsStudy design and patient populationAn observational, retrospective with prospectively gathered data, single-center, cohort study was performed. All consecutive patients with IBD diagnosis, followed in the IBD Unit of the Clinic University Hospital of Valencia, Spain, from 2007 until 2011 were screened for eligibility. Inclusion criteria were: firm IBD diagnosis, age >18 years and, at least, a single exposure to biological drugs (infliximab -IFX-, adalimumab -ADA-, vedolizumab -VDZ- or ustekinumab -USTE-). Patients with irregular follow-up or non-adherent according to medical criteria, were excluded.

Data collection and follow-upData were collected from our single-center ENEIDA registry. The ENEIDA Registry is a prospectively maintained database of IBD patients of the Spanish Crohn's and Colitis Work Group (GETECCU), initiated in 2006. This registry includes demographic, clinical, endoscopic and therapeutic data. Patients were followed from date of diagnosis until date of death, last visit or study closure in December 2020.

Variables included when biological drug initiation were: age, sex, IBD type, phenotypic expression of the disease, extraintestinal manifestations, complications, type of biological treatment, previous biological treatments (or naïve), concomitant immune-modulators and disease duration.

Treatment discontinuation as the main outcome was recorded at any time during follow-up, including motivation for withdrawal and duration of treatment.

DefinitionsDiagnosis of IBD was made by local gastroenterologists based on standard clinical, endoscopic, and pathological criteria according to the European Crohn's and Colitis Organization (ECCO) consensus guidelines.11 Disease extent was determined with ileocolonoscopy and classified according to the Montreal classification.12 The maximum extent of disease at any time since diagnosis until biological treatment initiation was assigned for each patient. The extraintestinal manifestations taken into account were peripheral arthropathy, ankylosing spondylitis, sacroilitis, cutaneous (erythema nodosum or pyoderma gangrenosum), aphthous stomatitis, ophthalmic (iritis or episcleritis), primary sclerosing cholangitis and thrombosis. Complications considered were megacolon, major acute hemorrhage defined as hematochezia or melena with hemodynamic instability (hypotension or orthostatic change in vital signs) and/or an acute decrease in hemoglobin concentration of at least 2mg/dL compared with baseline, bowel perforation or intra-abdominal abscesses. Irregular follow-up was considered when the patient did not attend two consecutive appointments.

Biological treatment regimen for IBD was the same in all patients, based on Spanish-developed guidelines, which is in agreement with ECCO guidelines.13,14 Patients were regularly monitored at the IBD Unit and intensification of treatment was performed taking into account both symptoms and drug levels. Medication exposure was defined as the administration of, at least, one dose of an IBD-related drug. Disease activity at the time of biological drug initiation was assessed based on the Harvey–Bradshaw index15 or partial Mayo score,16 calprotectin levels and/or endoscopy activity evaluated with endoscopic SESCD,17 Mayo score16 or Rutgeerts18 when available. Treatment discontinuation included the interruption of medication due to primary non-response (PNR), secondary loss of response (SLR) or adverse events (AE). PNR was considered when lack of response during the first 16 weeks after initiation of biological drug, despite intensification or modifications in concomitant drugs, led to the suspension of treatment. SLR was taken into account when the appearance of symptoms or intestinal inflammation assessed by an elevated calprotectin or activity on endoscopy, led to the suspension of treatment throughout follow-up. AE were categorized into immune-mediated (infusion reactions, flu-like syndrome, chronic hypersensitivity and paradoxical reactions), infections, neoplasms, hematological toxicity and others (including those unspecific or not described but that had a temporary association with the drug and remitted when it was discontinued).19

Genotypic analysisHLA-DQA1 low and high-resolution genotyping was performed by polymerase chain reaction with sequence-specific primers according to the method described by Olerup et al.20 Genomic DNA was isolated from nucleated cells by Magtration® technology.21 Each PCR reaction was performed on about 80ng of extracted DNA, using 0.15 units of Taq DNA polymerase (AmpliTaq® DNA Polymerase, Applied Biosystems, The Netherlands), and Olerup commercial primers (Olerup SSP AB, Stockholm, Sweden), according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR was carried out in a final volume of 10μL in a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, The Netherlands). An initial denaturizing step at 94°C for 2min was followed by 10 two-temperature cycles (94°C for 10s and 65°C for 60s) and 20 three-temperature cycles (94°C for 10s, 61°C for 50s and 72°C for 30s). Detection of amplified alleles was carried out by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Statistical analysisQualitative variables were expressed as frequencies (%) and quantitative variables as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR). Univariate analysis was performed to compare genetic factors, demographic variables, phenotypic expression, extraintestinal manifestations, complications, concomitant treatments and type of biological drugs with treatment discontinuation. Comparison between groups was made using the t-test or Mann–Whitney U test for continuous data and the chi-square test or Fisher's test for categorical data, as required. Measures of association between qualitative variables were reported as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Time-to-treatment discontinuation was calculated with the Kaplan–Meier curve from the date of biological treatment initiation to the date of biological drug withdrawal, death or study closure, whichever came first. Cox proportional hazard regression was used to evaluate the independent contribution of each factor on time-to-treatment interruption. These results were expressed as hazard ratios (HR) with respective 95% CI. All statistical tests were two-sided. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Covariates showing a clinical and statistical significance or participating as a confounding factor for the variable of interest were included in the multivariable models. All analyses were performed with the SPSS V22.0 software package.

ResultsStudy populationWe had determined HLA-DQ A1*05 on 457 consecutive patients of which 150 were eligible because they were on biologics (108 CD and 42 UC, Fig. 1): 91 (61%) males and 59 (39%) females. The median age at IBD diagnosis was 26 in CD patients and 28 in UC patients. Mean follow-up from date of diagnosis was 21 (SD 7) years.

Patients characteristics according to HLA-DQA1*05Prevalence of HLA-DQA1*05 was 40% (95% CI=32–48) in the total population (14% with two HLA DQ-A1*05 alleles), with a prevalence of 38% (95% CI=23–53) in UC and 41% (95% CI=31–50) in CD (p=0.766). A higher proportion of extensive UC (OR=1.8; 95% CI=1.4–2.5; p=0.033) and a tendency to present more CD with perianal involvement (p=0.059) were observed in cases with positive HLA-DQA1*05 (Supplementary Table 1). There were no significant differences in follow-up between patients with or without positive HLA-DQA1*05 (22±8 vs. 20±7; p=0.073).

Biological regimensA total of 312 biological treatments were administered (219 in CD and 93 in UC) during follow-up. Median number of biological drugs received by patient was 2 (IQR 1–3), in both CD and UC patients. A higher proportion of naïve patients received IFX with respect to non-naïve (63% vs. 29%; OR=4.170; 95% CI=2.6–6.7; p<0.001) while more non-naïve patients were treated with ADA (41% vs. 30%; OR=0.615; 95% CI=0.381–0.991; p=0.045), VDZ (13% vs. 2%; OR=0.100; 95% CI=0.023–0.431; p<0.001) or USTE (18% vs. 6%; OR=0.298; 95% CI=0.133–0.671; p=0.002), both in CD and UC. Similarly, associated immune-modulator (IMM) treatment was more frequent in patients that received IFX (51% vs. 39%; OR=1.684; 95% CI=1.060–2.677; p=0.027) while no significant differences were observed with ADA (33% vs. 38%; OR=0.787; 95% CI=0.485–1.275; p=0.333), VDZ (8% vs. 9%; OR=0.873; 95% CI=0.376–2.026; p=0.751) or USTE (9% vs. 15%; OR=0.594; 95% CI=0.285–1.240; p=0.162). The main indication for a biological drug was disease flare, and this group of patients had a significantly higher probability of receiving IFX (89% vs. 76%; OR=2.567; 95% CI=1.357–4.855; p=0.003) and lower of ADA (72% vs. 87%; OR=0.408; 95% CI=0.228–0.728; p=0.002). Biological treatments according to genotypic analysis is described in Supplementary Table 2.

Motivation for biological treatment discontinuationOf the 312 biological drugs, 147 (47%) were discontinued during study follow-up. The cumulative probability of treatment discontinuation was 30%, 41% and 56% at 1, 2 and 5 years of biological treatment initiation.

The reasons for treatment discontinuation were loss of response and AE in 79 (25%) and 68 (22%) of biologic treatment, respectively, without significant differences in patients with and without positive HLA-DQA1*05 (p=0.241). Mean time for biological treatment discontinuation was significantly lower in patients with SLR (22 –95% CI=17–27 – vs. 59 – 95% CI=50–68 – months; log rank=22.554; p<0.001) or AE (23 – 95% CI=16–30 – vs. 59 – 95% CI=50–68 – months; log rank=42.753; p<0.001).

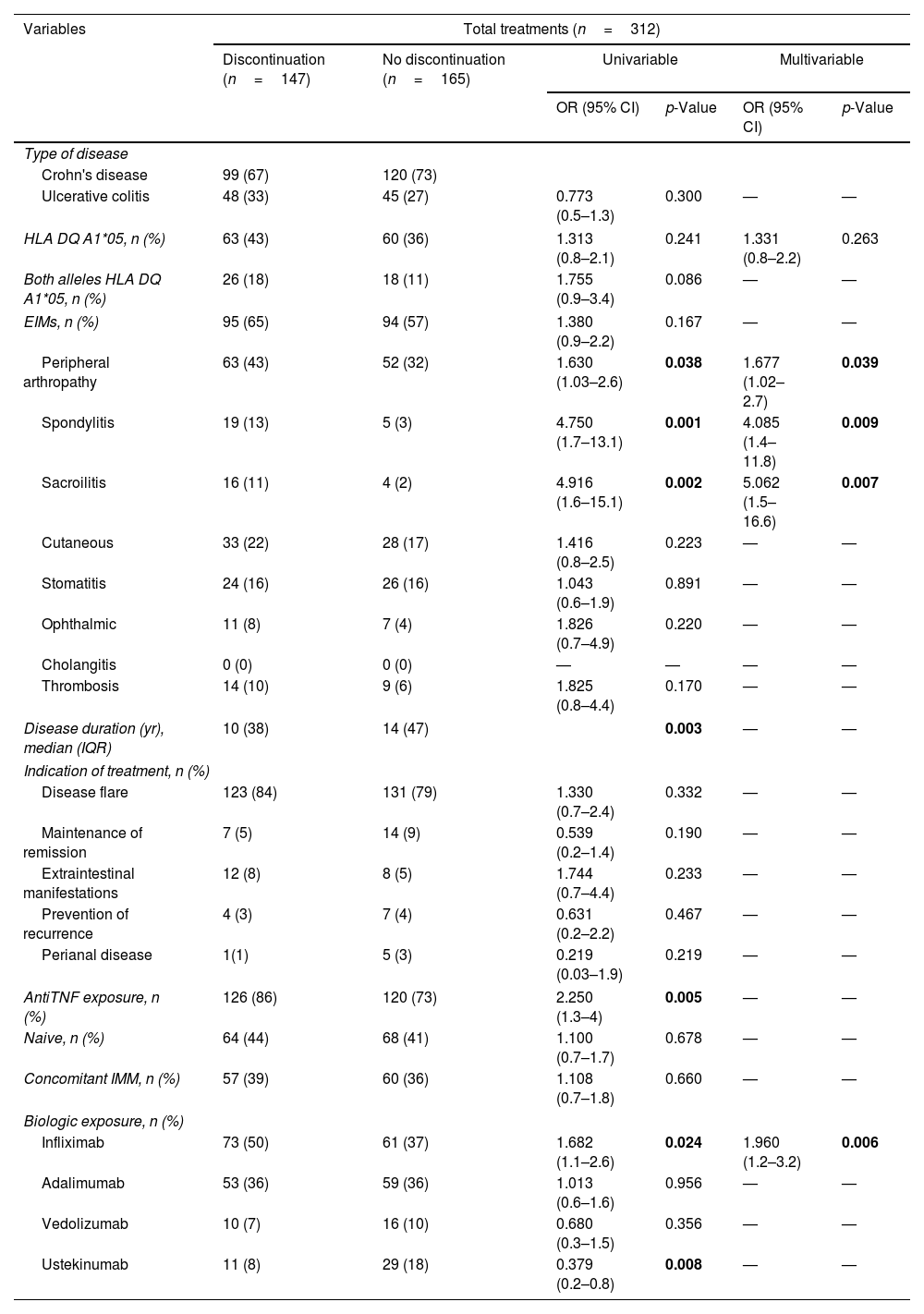

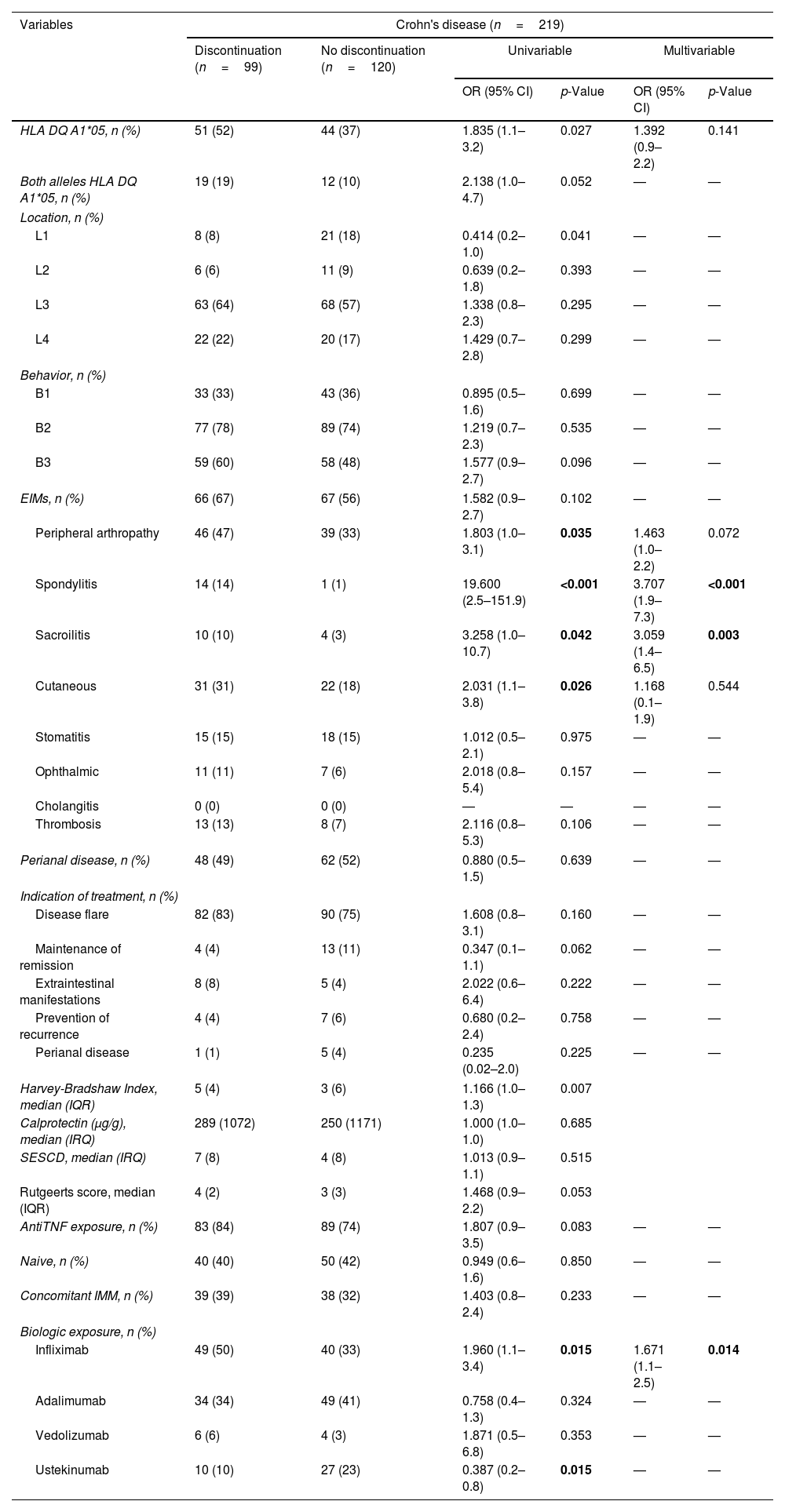

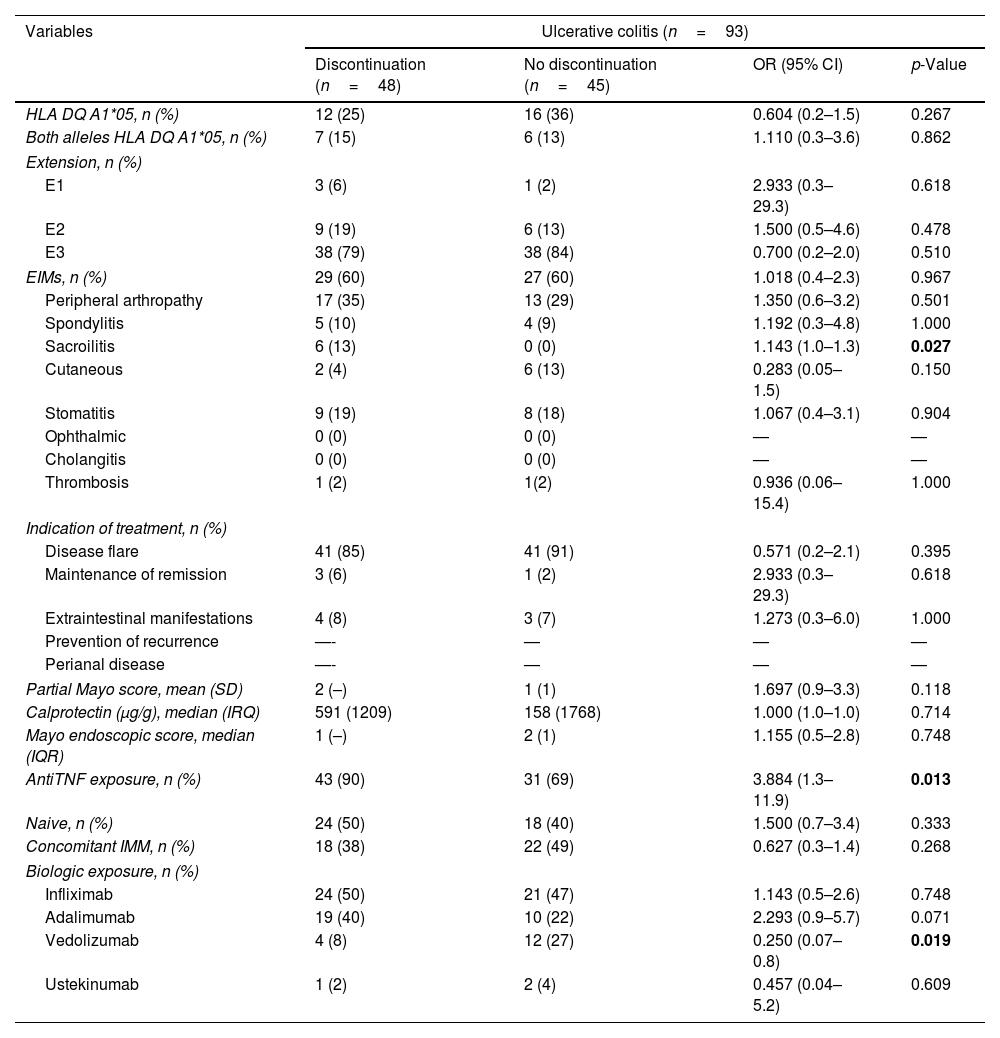

Risk factors for treatment discontinuationRisk factors for treatment discontinuation are shown in Tables 1–3, for all the cases, patients with CD and patients with UC, respectively.

Risk factors for treatment discontinuation.

| Variables | Total treatments (n=312) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discontinuation (n=147) | No discontinuation (n=165) | Univariable | Multivariable | |||

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |||

| Type of disease | ||||||

| Crohn's disease | 99 (67) | 120 (73) | ||||

| Ulcerative colitis | 48 (33) | 45 (27) | 0.773 (0.5–1.3) | 0.300 | — | — |

| HLA DQ A1*05, n (%) | 63 (43) | 60 (36) | 1.313 (0.8–2.1) | 0.241 | 1.331 (0.8–2.2) | 0.263 |

| Both alleles HLA DQ A1*05, n (%) | 26 (18) | 18 (11) | 1.755 (0.9–3.4) | 0.086 | — | — |

| EIMs, n (%) | 95 (65) | 94 (57) | 1.380 (0.9–2.2) | 0.167 | — | — |

| Peripheral arthropathy | 63 (43) | 52 (32) | 1.630 (1.03–2.6) | 0.038 | 1.677 (1.02–2.7) | 0.039 |

| Spondylitis | 19 (13) | 5 (3) | 4.750 (1.7–13.1) | 0.001 | 4.085 (1.4–11.8) | 0.009 |

| Sacroilitis | 16 (11) | 4 (2) | 4.916 (1.6–15.1) | 0.002 | 5.062 (1.5–16.6) | 0.007 |

| Cutaneous | 33 (22) | 28 (17) | 1.416 (0.8–2.5) | 0.223 | — | — |

| Stomatitis | 24 (16) | 26 (16) | 1.043 (0.6–1.9) | 0.891 | — | — |

| Ophthalmic | 11 (8) | 7 (4) | 1.826 (0.7–4.9) | 0.220 | — | — |

| Cholangitis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — | — | — | — |

| Thrombosis | 14 (10) | 9 (6) | 1.825 (0.8–4.4) | 0.170 | — | — |

| Disease duration (yr), median (IQR) | 10 (38) | 14 (47) | 0.003 | — | — | |

| Indication of treatment, n (%) | ||||||

| Disease flare | 123 (84) | 131 (79) | 1.330 (0.7–2.4) | 0.332 | — | — |

| Maintenance of remission | 7 (5) | 14 (9) | 0.539 (0.2–1.4) | 0.190 | — | — |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | 12 (8) | 8 (5) | 1.744 (0.7–4.4) | 0.233 | — | — |

| Prevention of recurrence | 4 (3) | 7 (4) | 0.631 (0.2–2.2) | 0.467 | — | — |

| Perianal disease | 1(1) | 5 (3) | 0.219 (0.03–1.9) | 0.219 | — | — |

| AntiTNF exposure, n (%) | 126 (86) | 120 (73) | 2.250 (1.3–4) | 0.005 | — | — |

| Naive, n (%) | 64 (44) | 68 (41) | 1.100 (0.7–1.7) | 0.678 | — | — |

| Concomitant IMM, n (%) | 57 (39) | 60 (36) | 1.108 (0.7–1.8) | 0.660 | — | — |

| Biologic exposure, n (%) | ||||||

| Infliximab | 73 (50) | 61 (37) | 1.682 (1.1–2.6) | 0.024 | 1.960 (1.2–3.2) | 0.006 |

| Adalimumab | 53 (36) | 59 (36) | 1.013 (0.6–1.6) | 0.956 | — | — |

| Vedolizumab | 10 (7) | 16 (10) | 0.680 (0.3–1.5) | 0.356 | — | — |

| Ustekinumab | 11 (8) | 29 (18) | 0.379 (0.2–0.8) | 0.008 | — | — |

Abbreviations: EIMs, extraintestinal manifestations; IMM, immune-modulator.

Risk factors for treatment discontinuation in CD patients.

| Variables | Crohn's disease (n=219) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discontinuation (n=99) | No discontinuation (n=120) | Univariable | Multivariable | |||

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |||

| HLA DQ A1*05, n (%) | 51 (52) | 44 (37) | 1.835 (1.1–3.2) | 0.027 | 1.392 (0.9–2.2) | 0.141 |

| Both alleles HLA DQ A1*05, n (%) | 19 (19) | 12 (10) | 2.138 (1.0–4.7) | 0.052 | — | — |

| Location, n (%) | ||||||

| L1 | 8 (8) | 21 (18) | 0.414 (0.2–1.0) | 0.041 | — | — |

| L2 | 6 (6) | 11 (9) | 0.639 (0.2–1.8) | 0.393 | — | — |

| L3 | 63 (64) | 68 (57) | 1.338 (0.8–2.3) | 0.295 | — | — |

| L4 | 22 (22) | 20 (17) | 1.429 (0.7–2.8) | 0.299 | — | — |

| Behavior, n (%) | ||||||

| B1 | 33 (33) | 43 (36) | 0.895 (0.5–1.6) | 0.699 | — | — |

| B2 | 77 (78) | 89 (74) | 1.219 (0.7–2.3) | 0.535 | — | — |

| B3 | 59 (60) | 58 (48) | 1.577 (0.9–2.7) | 0.096 | — | — |

| EIMs, n (%) | 66 (67) | 67 (56) | 1.582 (0.9–2.7) | 0.102 | — | — |

| Peripheral arthropathy | 46 (47) | 39 (33) | 1.803 (1.0–3.1) | 0.035 | 1.463 (1.0–2.2) | 0.072 |

| Spondylitis | 14 (14) | 1 (1) | 19.600 (2.5–151.9) | <0.001 | 3.707 (1.9–7.3) | <0.001 |

| Sacroilitis | 10 (10) | 4 (3) | 3.258 (1.0–10.7) | 0.042 | 3.059 (1.4–6.5) | 0.003 |

| Cutaneous | 31 (31) | 22 (18) | 2.031 (1.1–3.8) | 0.026 | 1.168 (0.1–1.9) | 0.544 |

| Stomatitis | 15 (15) | 18 (15) | 1.012 (0.5–2.1) | 0.975 | — | — |

| Ophthalmic | 11 (11) | 7 (6) | 2.018 (0.8–5.4) | 0.157 | — | — |

| Cholangitis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — | — | — | — |

| Thrombosis | 13 (13) | 8 (7) | 2.116 (0.8–5.3) | 0.106 | — | — |

| Perianal disease, n (%) | 48 (49) | 62 (52) | 0.880 (0.5–1.5) | 0.639 | — | — |

| Indication of treatment, n (%) | ||||||

| Disease flare | 82 (83) | 90 (75) | 1.608 (0.8–3.1) | 0.160 | — | — |

| Maintenance of remission | 4 (4) | 13 (11) | 0.347 (0.1–1.1) | 0.062 | — | — |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | 8 (8) | 5 (4) | 2.022 (0.6–6.4) | 0.222 | — | — |

| Prevention of recurrence | 4 (4) | 7 (6) | 0.680 (0.2–2.4) | 0.758 | — | — |

| Perianal disease | 1 (1) | 5 (4) | 0.235 (0.02–2.0) | 0.225 | — | — |

| Harvey-Bradshaw Index, median (IQR) | 5 (4) | 3 (6) | 1.166 (1.0–1.3) | 0.007 | ||

| Calprotectin (μg/g), median (IRQ) | 289 (1072) | 250 (1171) | 1.000 (1.0–1.0) | 0.685 | ||

| SESCD, median (IRQ) | 7 (8) | 4 (8) | 1.013 (0.9–1.1) | 0.515 | ||

| Rutgeerts score, median (IQR) | 4 (2) | 3 (3) | 1.468 (0.9–2.2) | 0.053 | ||

| AntiTNF exposure, n (%) | 83 (84) | 89 (74) | 1.807 (0.9–3.5) | 0.083 | — | — |

| Naive, n (%) | 40 (40) | 50 (42) | 0.949 (0.6–1.6) | 0.850 | — | — |

| Concomitant IMM, n (%) | 39 (39) | 38 (32) | 1.403 (0.8–2.4) | 0.233 | — | — |

| Biologic exposure, n (%) | ||||||

| Infliximab | 49 (50) | 40 (33) | 1.960 (1.1–3.4) | 0.015 | 1.671 (1.1–2.5) | 0.014 |

| Adalimumab | 34 (34) | 49 (41) | 0.758 (0.4–1.3) | 0.324 | — | — |

| Vedolizumab | 6 (6) | 4 (3) | 1.871 (0.5–6.8) | 0.353 | — | — |

| Ustekinumab | 10 (10) | 27 (23) | 0.387 (0.2–0.8) | 0.015 | — | — |

Abbreviations: EIMS, extraintestinal manifestations; IMM, immune-modulator.

Risk factors for treatment discontinuation in UC.

| Variables | Ulcerative colitis (n=93) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discontinuation (n=48) | No discontinuation (n=45) | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| HLA DQ A1*05, n (%) | 12 (25) | 16 (36) | 0.604 (0.2–1.5) | 0.267 |

| Both alleles HLA DQ A1*05, n (%) | 7 (15) | 6 (13) | 1.110 (0.3–3.6) | 0.862 |

| Extension, n (%) | ||||

| E1 | 3 (6) | 1 (2) | 2.933 (0.3–29.3) | 0.618 |

| E2 | 9 (19) | 6 (13) | 1.500 (0.5–4.6) | 0.478 |

| E3 | 38 (79) | 38 (84) | 0.700 (0.2–2.0) | 0.510 |

| EIMs, n (%) | 29 (60) | 27 (60) | 1.018 (0.4–2.3) | 0.967 |

| Peripheral arthropathy | 17 (35) | 13 (29) | 1.350 (0.6–3.2) | 0.501 |

| Spondylitis | 5 (10) | 4 (9) | 1.192 (0.3–4.8) | 1.000 |

| Sacroilitis | 6 (13) | 0 (0) | 1.143 (1.0–1.3) | 0.027 |

| Cutaneous | 2 (4) | 6 (13) | 0.283 (0.05–1.5) | 0.150 |

| Stomatitis | 9 (19) | 8 (18) | 1.067 (0.4–3.1) | 0.904 |

| Ophthalmic | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — | — |

| Cholangitis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — | — |

| Thrombosis | 1 (2) | 1(2) | 0.936 (0.06–15.4) | 1.000 |

| Indication of treatment, n (%) | ||||

| Disease flare | 41 (85) | 41 (91) | 0.571 (0.2–2.1) | 0.395 |

| Maintenance of remission | 3 (6) | 1 (2) | 2.933 (0.3–29.3) | 0.618 |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | 4 (8) | 3 (7) | 1.273 (0.3–6.0) | 1.000 |

| Prevention of recurrence | —- | — | — | — |

| Perianal disease | —- | — | — | — |

| Partial Mayo score, mean (SD) | 2 (–) | 1 (1) | 1.697 (0.9–3.3) | 0.118 |

| Calprotectin (μg/g), median (IRQ) | 591 (1209) | 158 (1768) | 1.000 (1.0–1.0) | 0.714 |

| Mayo endoscopic score, median (IQR) | 1 (–) | 2 (1) | 1.155 (0.5–2.8) | 0.748 |

| AntiTNF exposure, n (%) | 43 (90) | 31 (69) | 3.884 (1.3–11.9) | 0.013 |

| Naive, n (%) | 24 (50) | 18 (40) | 1.500 (0.7–3.4) | 0.333 |

| Concomitant IMM, n (%) | 18 (38) | 22 (49) | 0.627 (0.3–1.4) | 0.268 |

| Biologic exposure, n (%) | ||||

| Infliximab | 24 (50) | 21 (47) | 1.143 (0.5–2.6) | 0.748 |

| Adalimumab | 19 (40) | 10 (22) | 2.293 (0.9–5.7) | 0.071 |

| Vedolizumab | 4 (8) | 12 (27) | 0.250 (0.07–0.8) | 0.019 |

| Ustekinumab | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 0.457 (0.04–5.2) | 0.609 |

Abbreviations: EIMs, extraintestinal manifestations; IMM, immune-modulator.

Anti-TNF therapy was associated with treatment discontinuation (OR=2.250; 95% CI=1.266–3.999; p=0.005), mainly with IFX (OR=1.682; 95% CI=1.070–2.643; p=0.024). Shorter disease duration at the time of biological treatment initiation was associated with higher treatment interruption (OR=0.931; 95% CI=0.903–0.961; p<0.001). Some of the extraintestinal manifestations were also associated with biological drug discontinuation, including peripheral arthropathy (OR=1.630; 95% CI=1.026–2.590; p=0.038); ankylosing spondylitis (OR=4.750; 95% CI=1.726–13.070; p=0.001) or sacroilitis (OR=4.916; 95% CI=1.605–15.062; p=0.002). Multivariable analysis including significant factors of the univariable analyses and HLA-DQ A1*05 kept IFX therapy, disease duration and extraintestinal manifestations as significant factors of treatment discontinuation while HLA-DQA1*05 did not show significant influence (Table 1).

In patients with CD, HLA-DQA1*05 positive had a higher risk of treatment discontinuation in univariable analyses (p=0.027). Treatment discontinuation was also associated with IFX and several extraintestinal manifestations (peripheral arthropathy, ankylosing spondylitis, sacroilitis and cutaneous manifestations). Multivariable analysis kept IFX therapy, spondylitis and sacroileitis as significant factors of treatment discontinuation, but no HLA-DQ (Table 2).

Cause and time-to-treatment interruptionA higher proportion of PNR was seen in patients with UC than with CD (HR=4.998; 95% CI=1.707–14.629; p=0.003), mainly associated with extensive colitis (HR=3.680; 95% CI=1.334–10.150; p=0.012). Only disease flare as indication of biological treatment was associated to shorter time-to-discontinuation due to SLR (HR=2.315; 95% CI=1.051–5.099; p=0.037) while HLA-DQA1*05 did not show significant influence (HR=1.231; 95% CI=0.757–2.005; p=0.400).

A higher risk of AE was observed in patients with two alleles of HLA-DQA1*05 (46% vs. 25%; OR=2.551; 95% CI=1.325–4.911; p=0.004), spondylitis (46% vs. 26%; OR=2.403; 95% CI=1.032–5.594; p=0.037) or on anti-TNF therapy (32% vs. 11%; OR=3.987; 95% CI=1.742–9.125; p=0.001). Among anti-TNF drugs, mainly IFX was associated to AE (37% vs. 21%; OR=2.197; 95% CI=1.326–3.639; p=0.002), most commonly immune-mediated (27% vs. 12%; OR=2.746; 95% CI=1.516–4.976; p=0.001) and specially the paradoxical ones (14% vs. 5%; OR=3.368; 95% CI=1.194–9.506; p=0.028). Time-to-discontinuation of biological treatment due to AE was shorter with IFX therapy (HR=2.459; 95% CI=1.482–4.080; p<0.001) or spondylitis (49 vs. 112 months; HR=2.459; 95% CI=1.778–6.896; p<0.001) while two alleles of HLA-DQA1*05 did not show significant influence (HR=1.619; 95% CI=0.904–2.898; p=0.105) in the multivariable cox-proportional analyses.

Treatment discontinuation according to the biological regimenFocusing on ADA treatment, cases with HLA-DQA1*05 showed shorter time-to-treatment withdrawal due to SLR (HR=2.255; 95% CI=1.070–4.754; p=0.033). This influence of HLA-DQA1*05 on time-to discontinuation of ADA therapy was only seen in patients without concomitant IMM treatment (HR=2.803; 95% CI=1.134–6.926; p=0.026) (Fig. 2A) or with CD (HR=3.492; 95% CI=1.388–8.783; p=0.008) (Fig. 2B) but it was not present in patients with IMM (HR=1.483; 95% CI=0.397–5.537; p=0.557) or with UC (HR=0.781; 95% CI=0.157–3.895; p=0.763). Multivariable cox proportional regression analyses maintained HLA-DQA1*05 (HR=2.484; 95% CI=1.171–5.273; p=0.018) and disease flare as indication for ADA (HR=4.728; 95% CI=1.355–16.502; p=0.015) as independent predictors of SLR. No significant influence of HLA-DQA1*05 was seen with IFX (HR=0.855; 95% CI=0.399–1.885; p=0.698), USTE (HR=1.001; 95% CI=0.222–4.507; p=0.999) or VDZ (HR=0.591; 95% CI=0.066–5.291; p=0.638) on time-to discontinuation due to SLR.

DiscussionTreatment of IBD must be personalized. In order to give or interrupt treatment, several aspects must be regarded: genetics, type of IBD, phenotype of disease, extraintestinal manifestations, indication of treatment and the inflammatory burden.1 About one third of the patients do not respond to AntiTNF-α induction (20–40% of CD and 30–40% UC patients)22 and another third of the patients lose response during maintenance treatment (CD shows an annual SLR to IFX of 13%23 and of 20% with ADA24).

Several studies have demonstrated that HLA-DQA1*05 is related to the development of antibodies against antiTNF drugs and to the SLR to antiTNF,2–5 which could be something to keep in mind when starting biologics. In clinical practice, being able to maintain treatment, despite immunogenicity, certain AE, or a loss of response, is a goal that can be solved with treatment modifications such as intensifications or adding IMM. We are frequently treating young patients that will need to be on biologics (intermittently or continuously) all their life, so maintenance is crucial, which is why we decided to use treatment discontinuation as the main outcome of our study. In concrete, we focused our analysis on the “negative” reasons for stopping treatment (loss of response or side effects), not those that were based on interrupting due to remission or the patient's will to stop.

In 2020, Sazonovs et al., published a study in which they had included 1240 CD naïve patients treated with IFX or ADA for a flare; they demonstrated that having one allele of HLA-DQ A1*05 conferred a double risk of developing anti-TNF antibodies.5 That same year, Wilson et al. published the results of a retrospective study of 262 CD patients treated with IFX in which they had evaluated the relationship between HLA-DQA1*05 and developing anti-TNF antibodies. 79% of the people that had at least one HLA-DQA1*05 allele developed anti-TNF antibodies, with a significantly higher risk than patients without the allele.4 Rodriguez-Alonso et al., carried out a retrospective study of 64 patients treated with IFX, who had been controlled until SLR. The multivariable analysis showed that having HLA-DQ A1*05 was the only factor associated to SLR.2 In two retrospective studies with small samples of patients (53 and 20 patients), the same group observed that HLA-DQ A1*05 was only significant in SLR of patients on ADA,3 and not on USTE.25

In our study, we observed that HLA-DQ A1*05 was related to a more frequent and earlier treatment withdrawal due to SLR in CD patients on ADA without IMM. Patients with combotherapy of ADA and IMM did not show this difference, probably due to a reduction in immunogenicity, as the mentioned studies suggested. Similar to studies such as Camps et al.’s,3 we observed the effect of this allele only in CD patients.

We also looked into the relationship of HLA and clinical factors. Extensive colitis has a higher inflammatory burden and is related to an increased risk of colectomy due to biological treatment failure.6 In agreement with previous results, we observed that extensive colitis was significantly associated with treatment interruption due to PNR. Similarly, indicating biologics for a flare of the disease was significantly associated with SLR, probably associated with more activity than when treatment is prescribed for remission maintenance or to prevent postoperative recurrence. At the same time, all of the UC patients that had at least one HLA-DQ A1*05 allele had extensive colitis and a statistically significant higher Mayo score (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2), suggesting that in UC population, HLA-DQ A1*05 may be associated with more active and extensive colitis, which was recently also observed in Nowak's pediatric population.26

With respect to the number of treatments the patient has received in relation to loss of response, ADA has previously demonstrated efficacy and safety in UC and CD naïve and not-naïve to biologics,8 although a considerably higher remission rate has been observed in patients who had not received IFX before being on ADA.27 We did not observe general differences in SLR according to being naïve or not. The IFX group had a higher proportion of naïve patients, whereas the ADA group had a similar distribution of naïve vs. not naïve patients, with an important number of patients who had failed with IFX (generally SLR). Since the ADA group is where we obtained a relationship between the HLA-DQA1*05 and an increased SLR, genetics might be more relevant in non-naïve patients to set a daily-practice habit of associating IMM in second-line anti-TNF who are HLA-DQA1*05 positive.

Several studies have observed fewer infusion reactions, with less anti-IFX antibody formation, combining IFX and azathioprine.10 Studies with ADA are less clear, although a better response to induction treatment when combined with an IMM has been shown.27,28 When immunosuppression was analyzed with respect to PNR and SLR in both groups together (IFX and ADA), no differences were observed. However, a significantly earlier SLR was found in HLA-DQA1*05 positive patients treated with ADA alone, which was lost when an IMM was associated. As we previously mentioned on naïve and non-naïve patients treated with ADA, this might suggest that combotherapy with ADA and an IMM is probably especially useful in patients with this allele, to avoid early SLR.

The SUSTAIN study showed that loss of response with USTE was related to a high Harvey Bradshaw baseline index, and unrelated to concomitant IMM.29 We had 40 patients who had been on USTE. In line with what has been published,25 we did not find any relationship between having HLA-DQA1*05, SLR and USTE, regardless of them being naïve or not, or being on concomitant IMM.

Amiot et al. demonstrated that one third of the patients treated with VDZ had SLR, especially CD patients.30 We have not found any study addressing the relationship between HLA-DQA1*05 and loss of response or AE. We did not observe any relationship between this allele or any of the factors we studied with SLR. However, the sample was small (26 patients) and further research is needed to confirm that HLA-DQA1*05 does not influence response to VDZ.

Paradoxical reactions are more frequent with anti-TNF but also appear with other biologics. The SUSTAIN trial reported AE in 25 (7%) of the patients treated with USTE, mainly arthralgia and infections, with two cases of psoriasis.29 With respect to VDZ, a cohort study published in 2018 described skin and joint reactions/side effects, which included 11 psoriasis. Eight of the 14 that had cutaneous reactions, had also presented them with anti-TNF-α.31 In our study, IFX and spondylitis were significantly associated with treatment interruption due to AE. They were also related to the development of paradoxical reactions, as well as having two HLA-DQA1*05 alleles. Our study is in accordance with what has been published, because IFX is the most immunogenic of the biologics we have included.19 Spondylitis is an extraintestinal manifestation with considerable genetic background. Up to 75% of CD patients with spondylitis are HLA-B27 positive.1 Spondylitis is more frequent in colonic and perianal CD, and the risk of presenting it increases with disease duration and inflammatory burden.1 Many mechanisms have been proposed to explain why spondylitis occurs in IBD. One would be the appearance of antibodies and circulating immune complexes against common epitopes in different locations: colon, eyes, skin, joints and biliary epithelium.1 This has not been demonstrated, but it would explain the association we found between spondylitis and paradoxical reactions, because they would share the same mechanism of action. Genetic predisposition (mainly having two HLA-DQ A1*05 alleles) could be the basis of both mechanisms. In our study, CD patients with spondylitis had a tendency to carry one HLA-DQA1*05 allele (p=0.059), with a statistically significant difference if they had two HLA-DQ A1*05 alleles (p=0.010).

Our study has two main strong points that should be mentioned: we studied not only CD but also UC patients in whom HLA-DQ A1*05 has barely been analyzed, and considered not only anti-TNF, but also USTE and VDZ (the latter which, to our knowledge, has not been analyzed yet). These two points will probably be useful in clinical practice, a part from the reinforcement of taking HLA-DQA1*05 into account when prescribing ADA without IMM. In addition, we have studied treatments instead of patients so that we could correctly analyze first or second/third-line treatments. On the other hand, the limitations of the study are that, although data has been prospectively gathered, the analysis is retrospective, and that some of the subanalysis have a small sample size (for example with VDZ). Despite these limitations, the results are relevant because there are few studies that directly contribute to personalize medicine using HLA-DQ.

In conclusion, according to our results, HLA-DQA1*05 is relevant in SLR of IBD patients treated with ADA without IMM. In CD and UC patients treated with other biologics (IFX, USTE and VDZ), clinical factors associated with higher inflammatory activity were more important for treatment interruption, mainly extensive UC, extraintestinal manifestations and having indicated the biologic for a flare. Being on IFX, having associated spondylitis and carrying two HLA-DQ A1*05 alleles, were related to the appearance of paradoxical reactions (psoriasis, arthritis, suppurative hidradenitis and systemic erythematosus lupus) that let to treatment interruption.

Our results support some of the published data from other groups, and offer a new point of view suggesting that a combination of genetic and clinical factors can guide our treatment decisions. We would need prospective studies, with bigger simple sizes, to confirm our results.

SummaryWe present a retrospective study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) patients. Our aim was to evaluate the influence of HLA-DQ A1*05, along with other clinical and therapeutic factors, in biological treatment discontinuation due to loss of response or adverse events.

Ethical considerationsInformed consent to participate in our database was obtained from all patients. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of the hospital on 2021. The study complies with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and the Helsinki Declaration.

Conflict of interestMaría Rocío Davis González declares educational activities sponsored by MSD, Ferring, Abbvie, Janssen and Takeda.

Maria Pilar Ballester is supported by a Río Hortega award (CM19/00011), Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Spanish Ministry of Science and innovation).

Carles Suria declares educational activities and research projects sponsored by Ferring, Abbvie, Janssen and AztraZeneca.

David Marti-Aguado is recipient of a Río Hortega award (CM19/00212), Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Spanish Ministry of Science and innovation).

Miguel Mínguez Pérez has served as a speaker, a consultant, and advisory member for or has received research funding from MSD, Abbvie, Pfizer, Janssen, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Allergan.

Marta Maia Bosca-Watts declares educational activities, research projects, scientific meetings and advisory boards sponsored by MSD, Ferring, Abbvie, Janssen, Biogen and Takeda.

The other authors declare no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

We are grateful to the IBD Unit of the Clinic University Hospital of Valencia.