The Economic Activity Restriction (EAR) due to health conditions is being utilized as a foundational measure for the European indicator Healthy Life Years (HLY). The EAR group is experiencing limitations not only in economic activities but also in overall activities, and it is a population with a high likelihood of transitioning to mental illness due to health condition. However, few studies have investigated the relationship between EAR and mental illness. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to identify the association between EAR due to health conditions and mental illness for those aged 45 and older in South Korea.

MethodsWe obtained data from the 2006–2020 Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging. EAR was assessed using self-reported questionnaires based on the Global Activity Limitation Indicator. mental illness was assessed based on the diagnosis data for participants who had been diagnosed. After excluding missing values, the data of 9,574 participants were analyzed using the chi-square test, log-rank tests, and time-dependent Cox proportional hazard model to evaluate the association between EAR and mental illness.

ResultsOut of the 9,574 participants gathered at baseline, the mental illness rate was 4.8 %. The hazard ratio (HR) of mental illness in those in the “very probable” of EAR was 2.351 times higher (p-value <0.0001) compared with “not at all” of EAR. In model 1 which includes under 64 years, HR of mental illness in “very probable” of EAR was 3.679 times higher (p-value: 0.000) and in “probable” of EAR was 2.535 time higher (p-value: 0.001) compared with “not at all” of EAR.

ConclusionIf we provide opportunities to participate in community activities or provide the mental health promotion programs for middle-aged population who are experiencing EAR due to health condition, it is expected to prevent the deterioration of mental health and reduce the incidence of mental illness among the middle-aged Korean population.

In modern society, economic activity (EA) is defined as the most basic activity that can maintain personal health and economic satisfaction.1 Particularly through economic activities, one defines and recognizes oneself as a member of society rather than as an isolated entity in the larger social world.2 Continuous efforts to form and maintain interpersonal relationships are currently generating positive effects on the prevention of mental illness.3 However, in the case of employment stability in the Korean labor market, the average length of service is 5.6 years, which is very low compared to the organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) average of 9.5 years,4 and the average retirement age is around 50 years.5 Due to the characteristics of Korean corporate culture, in that health problems that inevitably occur with increasing age can lead to layoffs and recommended resignations, it is evaluated as a restrictive environment for stably carrying out economic activities.6

According to an announcement by the Korea Statistical Office,7 the employment rate of middle-aged and elderly individuals working for Korean companies is continuously decreasing, along with a high desire for EA, but the rate of economic activity restriction (EAR) due to health conditions is increasing.7 The Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare conducts an annual health and employment survey regarding whether individuals have experienced EAR due to health conditions. Based on this, they utilize the concept of “EAR due to health conditions” as a factor to measure age-specific involuntary unemployment.8 Globally, there is a single-item indicator called Global Activity Limitation Indicator (GALI) that assesses individual activity restriction (AR) due to health conditions.9-11 Using this indicator, according to the results of the investigation into EAR,12 the rate of AR due to health conditions for American adults was 4.3 %, but the rate of AR for Korean adults was 8.3 %, significantly higher than that of other countries. In particular, the AR rate for the elderly in Korea is 15.2 %, which becomes more severe as age increases.12

The EAR causes a decrease in income and social activity, as well as social isolation, which causes various social problems such as the deterioration of physical health, the occurrence of chronic diseases, and the induction of mental diseases.13,14 In particular, mental illness is an important challenge in modern society because it is a major cause of disability.15 According to the World Health Organization (WHO) report, the number of people with mental disorders such as dementia and depression worldwide exceeded 970 million in 2019.16

According to a European study,17 despite the desire for EA, the group that did not engage in EA due to personal health developed mental disorders, such as depression and anxiety. A previous study that analysed 1599,600 middle-aged Canadians revealed that the longer the period of involuntary unemployment due to health issues is for middle-aged people with a high desire and necessity for EA, the more different mental diseases such as depression, anxiety disorders, and dementia occur.18-20 In addition, a previous study in Korea analysed the association between the EAR and depression, targeting 8821 adults aged 45 years and older, the CED-10 score of the EAR was 2.55 points higher in the middle-aged and 0.50 points higher in the elderly than in the group without restrictions.21 As such, the mental health levels of the EAR group were found to be lower compared to the non-EAR group, and it can be inferred that the middle-aged EAR group may experience more mental health deterioration than the elderly. Furthermore, it has been reported that EA in the middle-aged group has greater utility in terms of quality of life, subjective health, and mental health compared to the elderly population.22

Although some studies have presented findings on the effect of EAR due to health condition on mental health, most studies were conducted in countries with not only higher employment stability than Korea, but also lower rates of EAR than Korea.17-20 As the results of studies conducted in Korea have identified a relationship between employment patterns and mental disorders, few studies have investigated the relationship between EAR and mental illness. Furthermore, there is a lack of clarity regarding the impact of EAR on mental health in the middle-aged and elderly populations in Korea respectively. Therefore, in consideration of these points, this study intends to analyze the effect that EAR have on mental illness in middle-aged and elderly people. Furthermore, a detailed analysis was conducted on the relationship between EAR and mental illness in middle-aged and elderly groups with different meanings for EA.

The research hypotheses presented in this study are as follows: First, as the intensity of EAR increases, the incidence of mental illness is expected to rise. Second, there will be a stronger association between EAR and mental illness among the middle-aged EAR group facing high economic burdens compared to the elderly EAR group.

Based on this, this study is intended to provide basic data to prevent the deterioration of mental illness in groups vulnerable to mental health issues.

MethodsData sourceThe data used for the analyses were derived from the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging (KLoSA) from 2006 to 2020. As a study that possesses both the strengths of cross-sectional and time series data, the KLoSA was conducted by repeatedly surveying identical content for the same respondents every year. Thus, all variables surveyed by the KLoSA were repeatedly measured from the first to fourth waves to collect observation cases at multiple points in time. This biennial survey involves multistage stratified sampling based on geographical areas and housing types across Korea. Participants were selected randomly using multistage stratified probability sampling to create a nationally representative sample of community-dwelling Koreans aged 45 and older. Participant selection was performed by the Korea Labor Institute, including individuals from both urban and rural areas. In case of refusal to participate, another participant was selected from an additional, similar sample from the same district.

In the first survey in 2006, 10,254 individuals from 6171 households (1.7 per household) were interviewed. The second survey, in 2008, followed up with 8875 participants, who represented 86.6 % of the original panel. The third survey, in 2010, followed up with 8229 participants, who represented 81.7 % of the original panel. The fourth survey, in 2012, followed up with 7813 participants, who represented 80.1 % of the original panel. The fifth survey, in 2014, followed up with 8387 participants (including 920 new participants), who represented 80.4 % of the original panel. The sixth survey, in 2016, followed up with 7893 participants (including 878 new participants), who represented 79.6 % of the original panel. The seventh survey, in 2018, followed up with 7491 participants (including 817 new participants) who represented 78.8 % of the original panel. Finally, the eighth survey, in 2020, followed up with 7000 participants (including 786 new participants) who represented 78.1 % of the original panel.

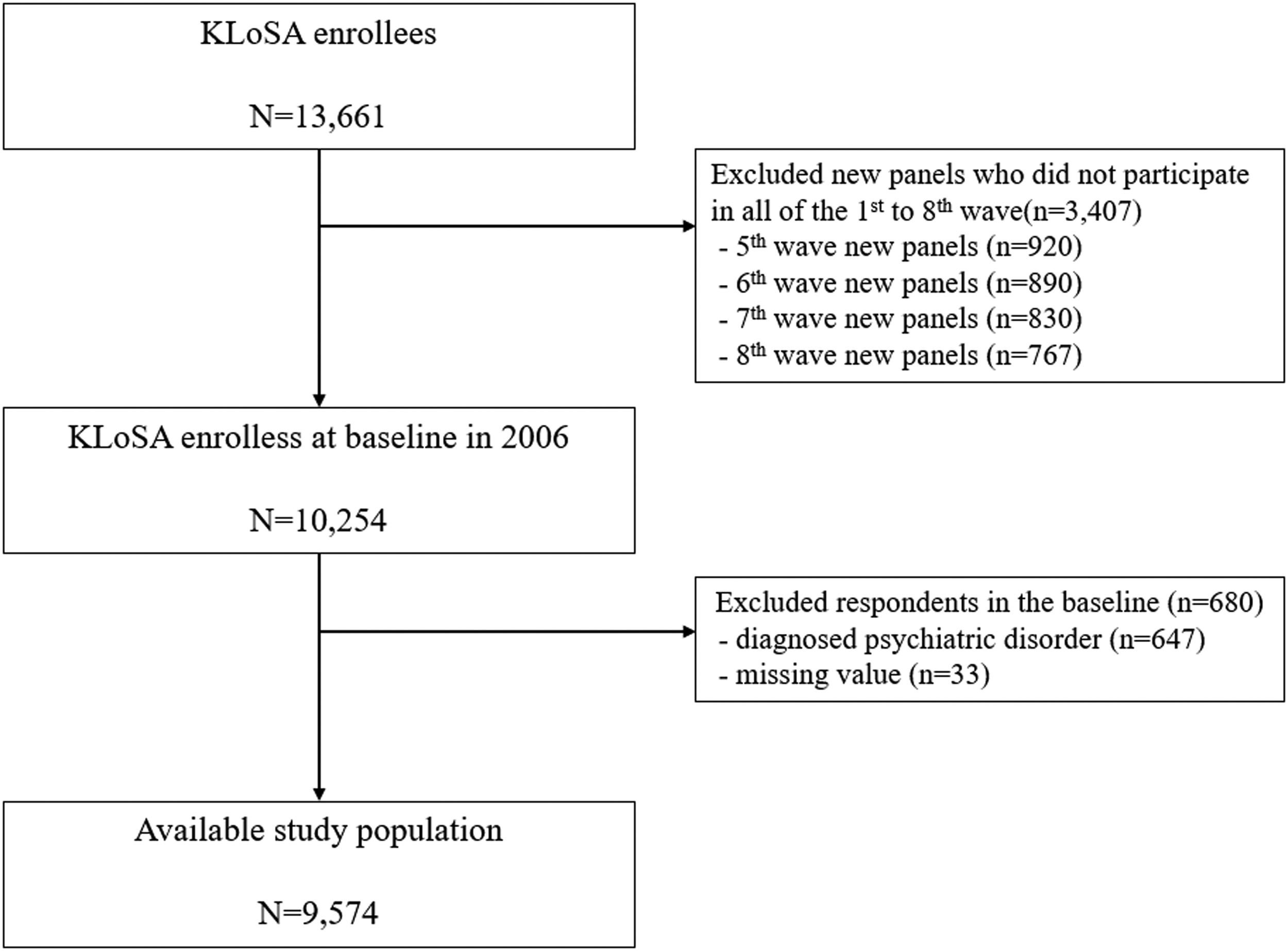

To investigate the association between EAR and mental illness, among 13,661 individuals who registered in the 1st-8th KLoSA, First, we excluded 3407 participants who newly added panels. Second, we excluded 647 respondents who were diagnosed psychiatric disorders by a doctor before surveying the KLoSA at baseline. Third, we removed 33 participants who lacked control variable information (8 participants who lacked education variable, 24 participants who lacked insurance variable and 1 participant who lacked smoking variable). Finally, we included 9574 participants at baseline (70.1 % of the total participants were retained in the sample). Fig. 1 depicts the flowchart for sample selection at baseline of this study.

Independent variableThe independent variable in this study was EAR due to health condition, and the indicator based on the Global Activity Limits Indicator (GALI) was “Do you have a problem with your work (activities) because of your health condition?”. The responses were assigned to 1 of 4 subcategories: “very probable”, “probable”, “probably not” and “not at all”. The GALI is a single-item survey instrument reported by the individual him or herself to assess health-related activity restrictions.11

Due to its reliance on a single-item measure, there are limitations in assessing the validity and reliability of this indicator. However, various prior studies have conducted examinations of the validity and reliability of the indicator, reporting sufficient levels of reliability and validity.23

Dependent variablesIncidence of mental illness over a maximum of 15 years was determined by the response of the following question by yes/no response to the question: “When was the first time you were diagnosed with a mental illness by a doctor?” The mental illness range is limited to depression, anxiety, insomnia, excessive stress, cognitive decline, and dementia.

Control variablesSocioeconomic and demographic factorsAge group was divided into four categories: 45–54, 55–64, 65–74 and ≥75 years. Educational level was categorized into four groups: elementary school or lower, middle school, high school, and college or higher. Sex was categorized as male or female. Residential region was categorized as metropolitan (Seoul), urban (Daejeon, Daegu, Busan, Incheon, Kwangju, or Ulsan), or rural (not classified as a city). Marital status was divided into three groups: married, separated, or divorced, and single. Current EA was categorized into yes or no and health insurance was categorized into national health insurance and medical aid.

Health status and behavioral factorsSmoking status was categorized into three groups: smoker, former smoker, and never. Alcohol use also was divided into three groups: drinker, former drinker, and never. Finally, the number of chronic diseases (hypertension, diabetes, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, cancer, chronic pulmonary disease, liver disease, cardiovascular disease, and cerebrovascular disease) was included as a covariate in our analyses.

Analytical approach and statisticsThe chi-square, log rank tests for Kaplan Meier curve as well as time-dependent Cox proportional hazards models, were used to analyze the association between the EAR and mental illness. Using time-dependent Cox proportional hazards models,24 adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to assess the relationship. Survival time, measured as the time interval between the date of enrollment and the date of diagnosis with mental illness or censoring (up to fifteen years), was the outcome variable. For all analyses, the criterion for statistical significance was p < 0.05, two-tailed. All analyses were conducted using the SAS statistical software package, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

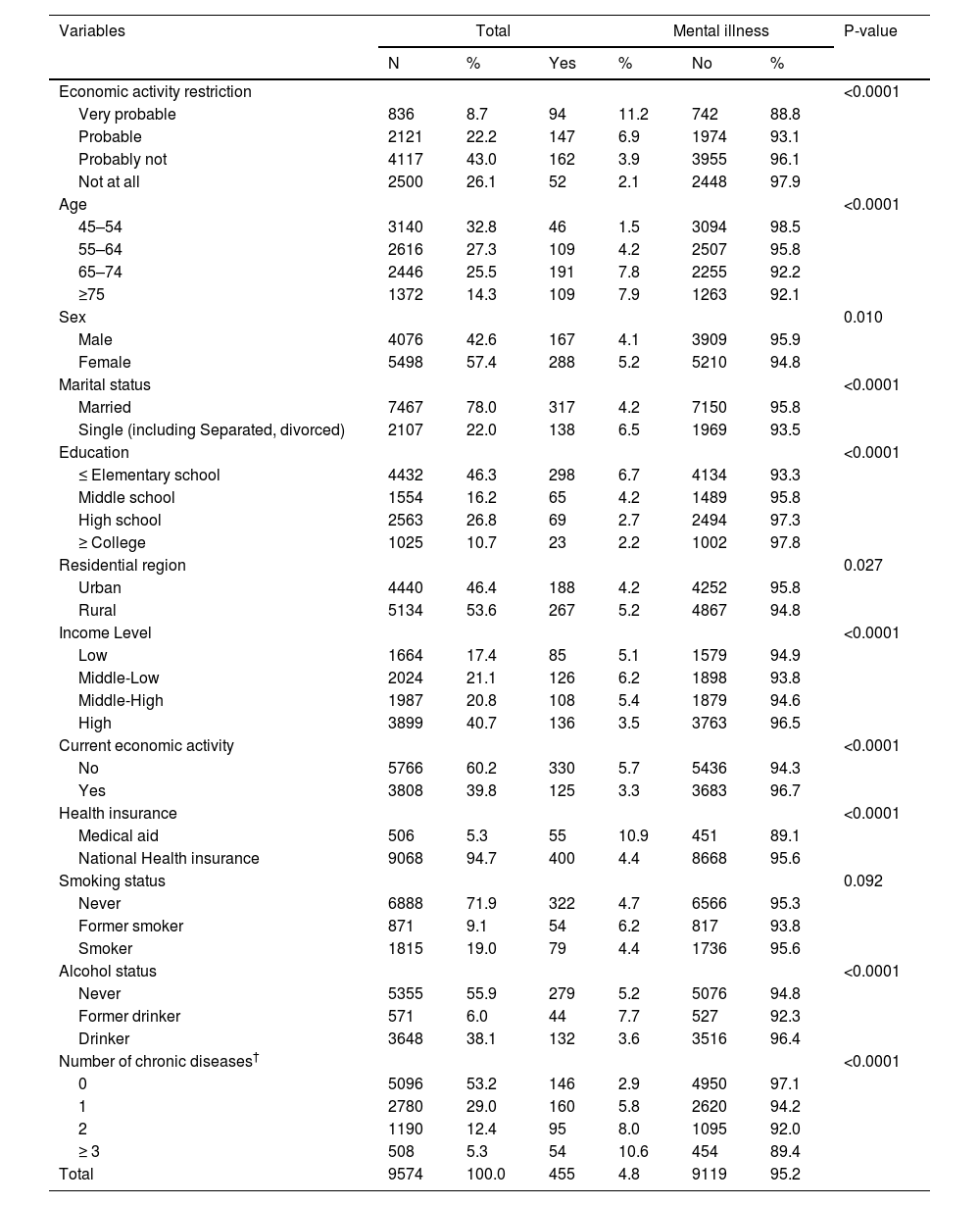

ResultsSample characteristicsBaseline general characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. Out of the 9574 participants gathered at baseline, the mental illness rate of the total participants was 4.8 % (455 individuals). 836 (8.7 %) participants were reported as ‘Very probable’ group, 2121 (22.2 %) participants were reported as ‘Probable’ group, 4117 (43.0 %) participants were reported as ‘Probably not’ group and 2500 (26.1 %) participants were reported as ‘Not at all’ group. In terms of mental illness rate, for the ‘Very probable’ group was 11.2 % (94 individuals), ‘Probable’ group was 6.9 % (147 individuals), ‘Probably not’ group was 3.9 % (162 individuals) and ‘Not at all’ group was 2.1 % (52 individuals). General characteristics of rest of the socioeconomic status (age, sex, marital status, education level, residential region, income level and current EA) and health status and risk behavior (health insurance, smoke status, alcohol status and no. chronic diseases) variables are also listed in Table 1.

General characteristics of subjects included for analysis.

| Variables | Total | Mental illness | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | Yes | % | No | % | ||

| Economic activity restriction | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Very probable | 836 | 8.7 | 94 | 11.2 | 742 | 88.8 | |

| Probable | 2121 | 22.2 | 147 | 6.9 | 1974 | 93.1 | |

| Probably not | 4117 | 43.0 | 162 | 3.9 | 3955 | 96.1 | |

| Not at all | 2500 | 26.1 | 52 | 2.1 | 2448 | 97.9 | |

| Age | <0.0001 | ||||||

| 45–54 | 3140 | 32.8 | 46 | 1.5 | 3094 | 98.5 | |

| 55–64 | 2616 | 27.3 | 109 | 4.2 | 2507 | 95.8 | |

| 65–74 | 2446 | 25.5 | 191 | 7.8 | 2255 | 92.2 | |

| ≥75 | 1372 | 14.3 | 109 | 7.9 | 1263 | 92.1 | |

| Sex | 0.010 | ||||||

| Male | 4076 | 42.6 | 167 | 4.1 | 3909 | 95.9 | |

| Female | 5498 | 57.4 | 288 | 5.2 | 5210 | 94.8 | |

| Marital status | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Married | 7467 | 78.0 | 317 | 4.2 | 7150 | 95.8 | |

| Single (including Separated, divorced) | 2107 | 22.0 | 138 | 6.5 | 1969 | 93.5 | |

| Education | <0.0001 | ||||||

| ≤ Elementary school | 4432 | 46.3 | 298 | 6.7 | 4134 | 93.3 | |

| Middle school | 1554 | 16.2 | 65 | 4.2 | 1489 | 95.8 | |

| High school | 2563 | 26.8 | 69 | 2.7 | 2494 | 97.3 | |

| ≥ College | 1025 | 10.7 | 23 | 2.2 | 1002 | 97.8 | |

| Residential region | 0.027 | ||||||

| Urban | 4440 | 46.4 | 188 | 4.2 | 4252 | 95.8 | |

| Rural | 5134 | 53.6 | 267 | 5.2 | 4867 | 94.8 | |

| Income Level | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Low | 1664 | 17.4 | 85 | 5.1 | 1579 | 94.9 | |

| Middle-Low | 2024 | 21.1 | 126 | 6.2 | 1898 | 93.8 | |

| Middle-High | 1987 | 20.8 | 108 | 5.4 | 1879 | 94.6 | |

| High | 3899 | 40.7 | 136 | 3.5 | 3763 | 96.5 | |

| Current economic activity | <0.0001 | ||||||

| No | 5766 | 60.2 | 330 | 5.7 | 5436 | 94.3 | |

| Yes | 3808 | 39.8 | 125 | 3.3 | 3683 | 96.7 | |

| Health insurance | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Medical aid | 506 | 5.3 | 55 | 10.9 | 451 | 89.1 | |

| National Health insurance | 9068 | 94.7 | 400 | 4.4 | 8668 | 95.6 | |

| Smoking status | 0.092 | ||||||

| Never | 6888 | 71.9 | 322 | 4.7 | 6566 | 95.3 | |

| Former smoker | 871 | 9.1 | 54 | 6.2 | 817 | 93.8 | |

| Smoker | 1815 | 19.0 | 79 | 4.4 | 1736 | 95.6 | |

| Alcohol status | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Never | 5355 | 55.9 | 279 | 5.2 | 5076 | 94.8 | |

| Former drinker | 571 | 6.0 | 44 | 7.7 | 527 | 92.3 | |

| Drinker | 3648 | 38.1 | 132 | 3.6 | 3516 | 96.4 | |

| Number of chronic diseases† | <0.0001 | ||||||

| 0 | 5096 | 53.2 | 146 | 2.9 | 4950 | 97.1 | |

| 1 | 2780 | 29.0 | 160 | 5.8 | 2620 | 94.2 | |

| 2 | 1190 | 12.4 | 95 | 8.0 | 1095 | 92.0 | |

| ≥ 3 | 508 | 5.3 | 54 | 10.6 | 454 | 89.4 | |

| Total | 9574 | 100.0 | 455 | 4.8 | 9119 | 95.2 | |

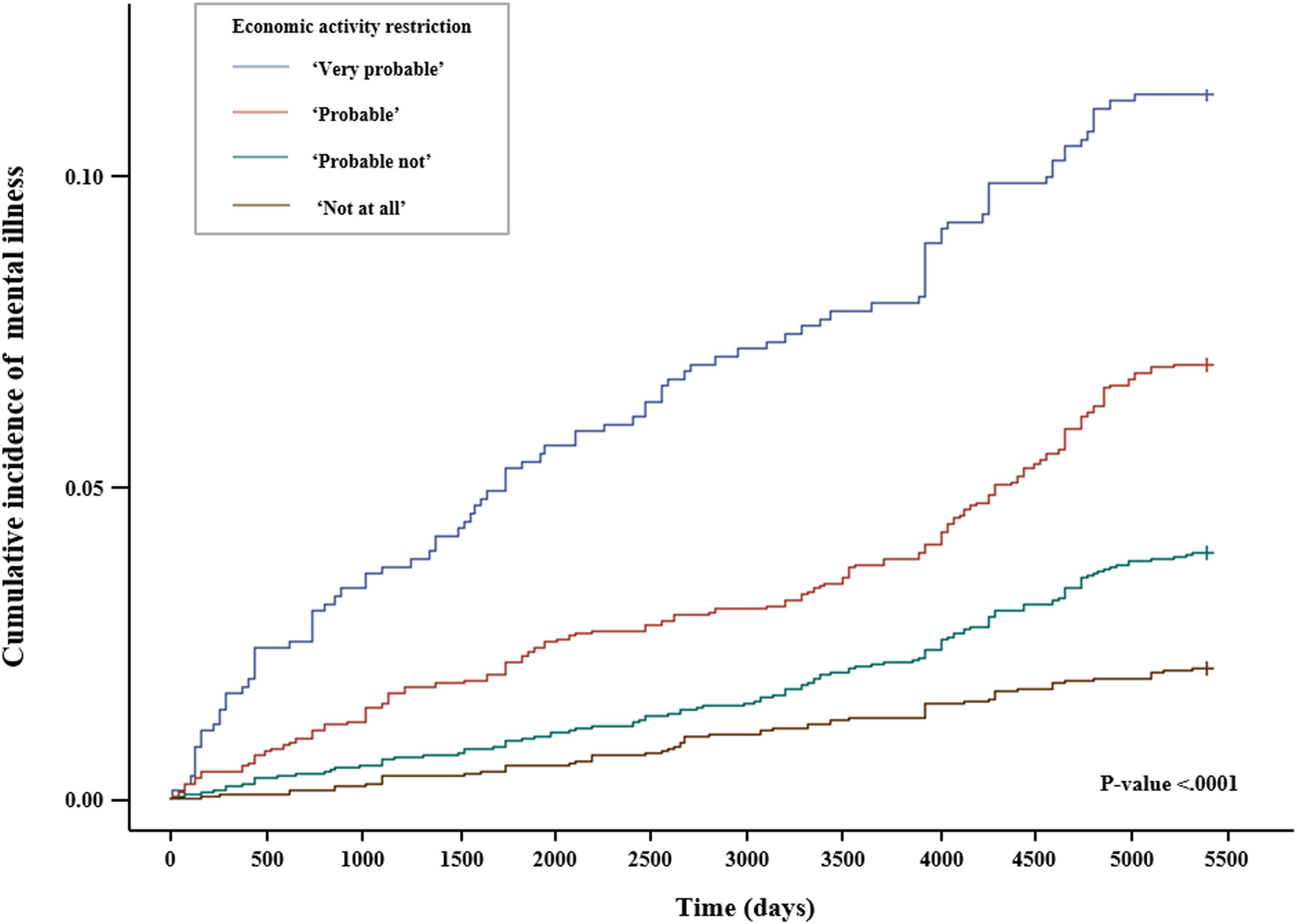

Fig. 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier curve. Results of log-rank test represented a significant difference in cumulative incidence of four groups for EAR and incidence of mental illness (p <0.0001).

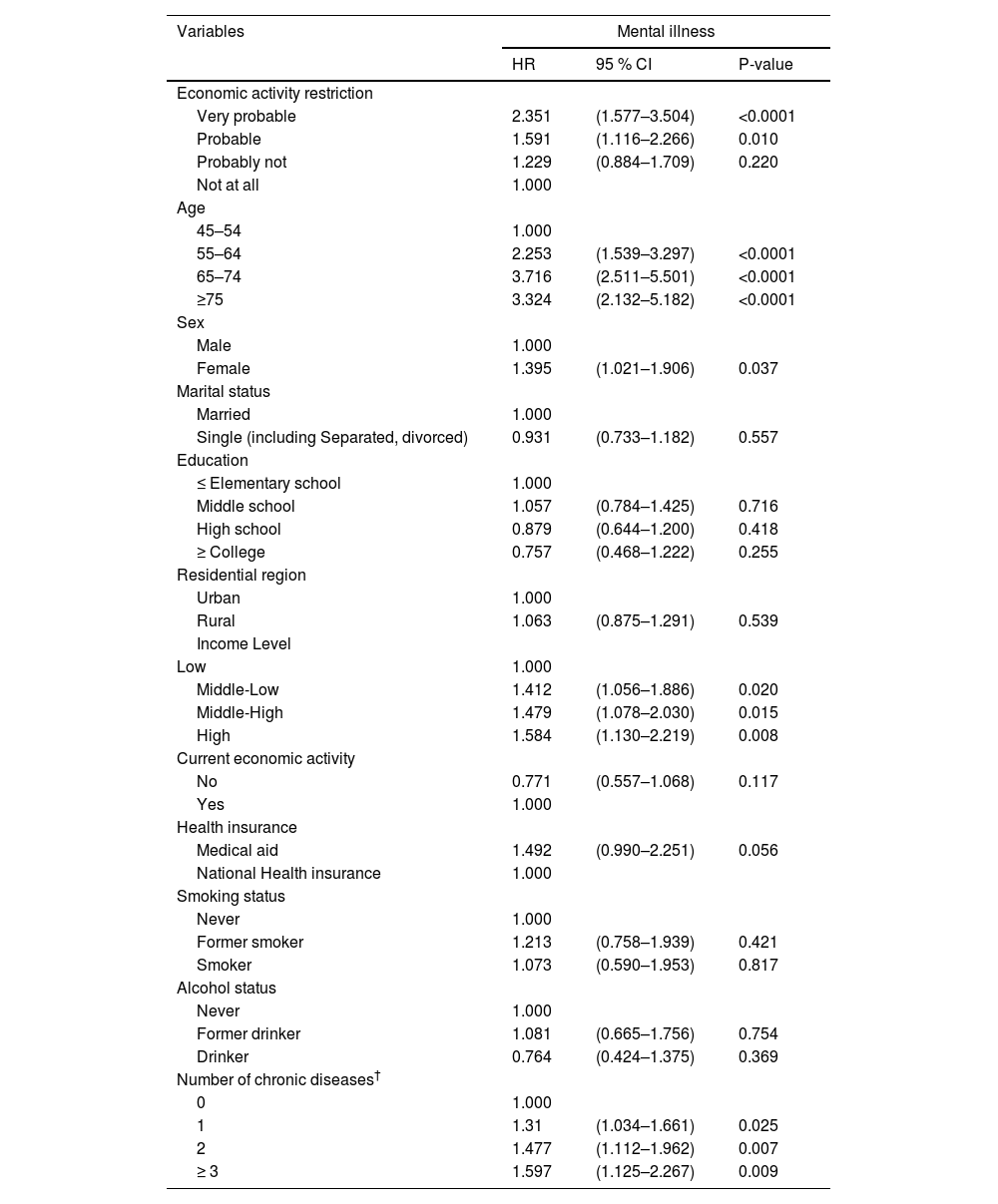

Relationship between EAR and mental illnessTable 2 shows the results of the time-dependent Cox proportional hazards model, which investigated the association between EAR and mental illness. Compared to those who responded ‘Not at all’ group, those who answered ‘Very probable’ had a high incidence of mental illness rate of 2.351 times (Hazard Ratio [HR]: 2.351, 95 % Confidence Interval [CI]: 1.577 – 3.504, P-value <0.0001). Those who answered ‘Probable’ had a high mental illness rate of 1.591 times (HR: 1.591, 95 % CI: 1.116 – 2.266, P-value: 0.010). and those who answered ‘Probably not’ had a high mental illness rate of 1.229 times (HR: 1.229, 95 % CI: 0.884 – 1.709, P-value: 0.220), but it was not statistically significant.

Time-dependent Cox proportional hazard regression analysis for the association between economic activity restriction and mental illness.

| Variables | Mental illness | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95 % CI | P-value | |

| Economic activity restriction | |||

| Very probable | 2.351 | (1.577–3.504) | <0.0001 |

| Probable | 1.591 | (1.116–2.266) | 0.010 |

| Probably not | 1.229 | (0.884–1.709) | 0.220 |

| Not at all | 1.000 | ||

| Age | |||

| 45–54 | 1.000 | ||

| 55–64 | 2.253 | (1.539–3.297) | <0.0001 |

| 65–74 | 3.716 | (2.511–5.501) | <0.0001 |

| ≥75 | 3.324 | (2.132–5.182) | <0.0001 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1.000 | ||

| Female | 1.395 | (1.021–1.906) | 0.037 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 1.000 | ||

| Single (including Separated, divorced) | 0.931 | (0.733–1.182) | 0.557 |

| Education | |||

| ≤ Elementary school | 1.000 | ||

| Middle school | 1.057 | (0.784–1.425) | 0.716 |

| High school | 0.879 | (0.644–1.200) | 0.418 |

| ≥ College | 0.757 | (0.468–1.222) | 0.255 |

| Residential region | |||

| Urban | 1.000 | ||

| Rural | 1.063 | (0.875–1.291) | 0.539 |

| Income Level | |||

| Low | 1.000 | ||

| Middle-Low | 1.412 | (1.056–1.886) | 0.020 |

| Middle-High | 1.479 | (1.078–2.030) | 0.015 |

| High | 1.584 | (1.130–2.219) | 0.008 |

| Current economic activity | |||

| No | 0.771 | (0.557–1.068) | 0.117 |

| Yes | 1.000 | ||

| Health insurance | |||

| Medical aid | 1.492 | (0.990–2.251) | 0.056 |

| National Health insurance | 1.000 | ||

| Smoking status | |||

| Never | 1.000 | ||

| Former smoker | 1.213 | (0.758–1.939) | 0.421 |

| Smoker | 1.073 | (0.590–1.953) | 0.817 |

| Alcohol status | |||

| Never | 1.000 | ||

| Former drinker | 1.081 | (0.665–1.756) | 0.754 |

| Drinker | 0.764 | (0.424–1.375) | 0.369 |

| Number of chronic diseases† | |||

| 0 | 1.000 | ||

| 1 | 1.31 | (1.034–1.661) | 0.025 |

| 2 | 1.477 | (1.112–1.962) | 0.007 |

| ≥ 3 | 1.597 | (1.125–2.267) | 0.009 |

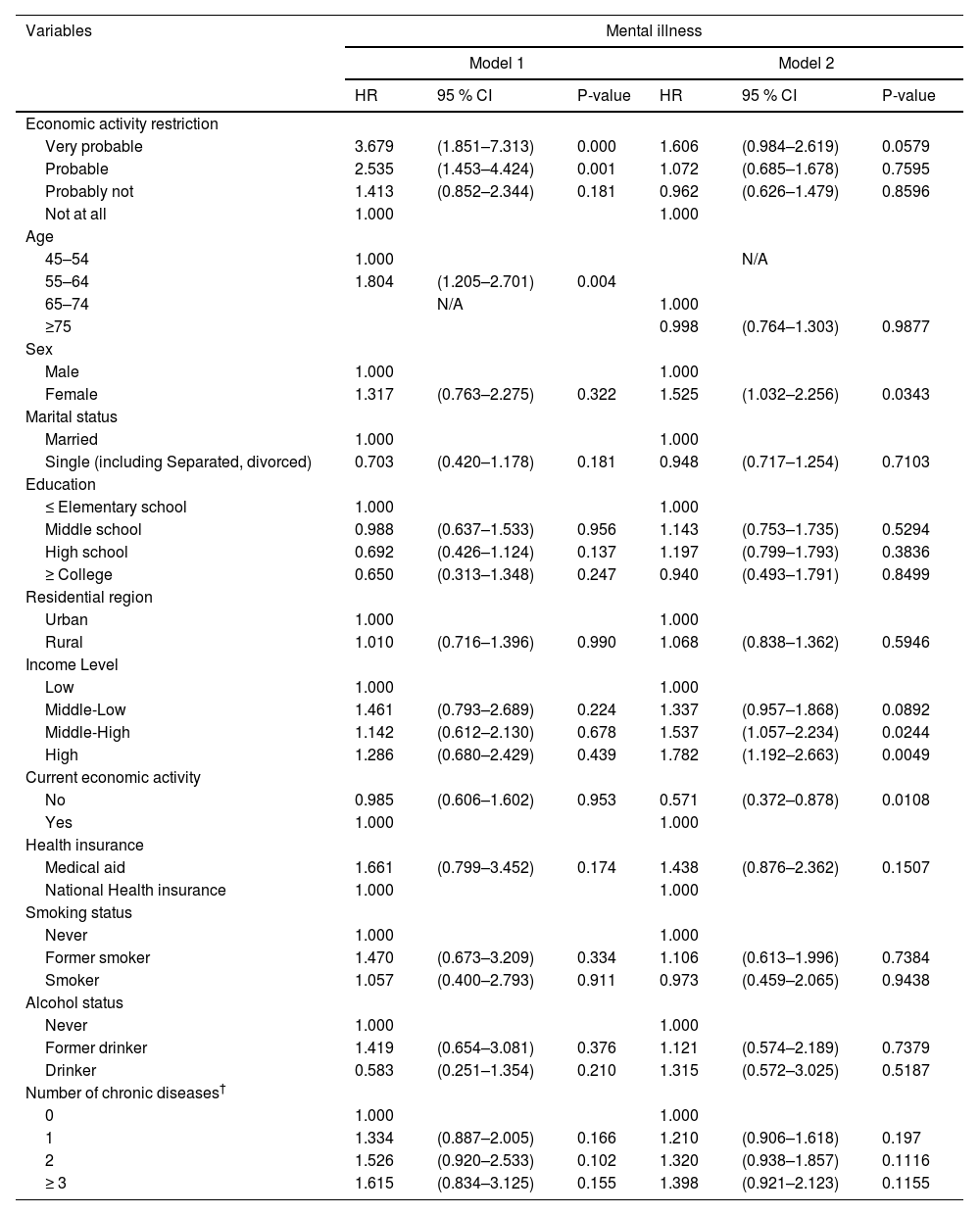

Table 3 shows the results of the subgroup analysis stratified by age. In Model 1 which included under 64 years participants, compared to ‘Not at all’ group, ‘Very probable’ group had a high mental illness rate of 3.679 times (HR: 3.679, 95 % CI: 1.851 – 7.313, P-value: 0.000). ‘Probable’ group had a high mental illness rate of 2.535 times (HR: 2.535, 95 % CI: 1.453 – 4.424, P-value: 0.001). In Model 2 which included over 65 years participants, there weren't find out the relationship between EAR and mental illness.

Subgroup analysis of association between economic activity restriction and mental illness stratified by age.

| Variables | Mental illness | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

| HR | 95 % CI | P-value | HR | 95 % CI | P-value | |

| Economic activity restriction | ||||||

| Very probable | 3.679 | (1.851–7.313) | 0.000 | 1.606 | (0.984–2.619) | 0.0579 |

| Probable | 2.535 | (1.453–4.424) | 0.001 | 1.072 | (0.685–1.678) | 0.7595 |

| Probably not | 1.413 | (0.852–2.344) | 0.181 | 0.962 | (0.626–1.479) | 0.8596 |

| Not at all | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Age | ||||||

| 45–54 | 1.000 | N/A | ||||

| 55–64 | 1.804 | (1.205–2.701) | 0.004 | |||

| 65–74 | N/A | 1.000 | ||||

| ≥75 | 0.998 | (0.764–1.303) | 0.9877 | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Female | 1.317 | (0.763–2.275) | 0.322 | 1.525 | (1.032–2.256) | 0.0343 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Single (including Separated, divorced) | 0.703 | (0.420–1.178) | 0.181 | 0.948 | (0.717–1.254) | 0.7103 |

| Education | ||||||

| ≤ Elementary school | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Middle school | 0.988 | (0.637–1.533) | 0.956 | 1.143 | (0.753–1.735) | 0.5294 |

| High school | 0.692 | (0.426–1.124) | 0.137 | 1.197 | (0.799–1.793) | 0.3836 |

| ≥ College | 0.650 | (0.313–1.348) | 0.247 | 0.940 | (0.493–1.791) | 0.8499 |

| Residential region | ||||||

| Urban | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Rural | 1.010 | (0.716–1.396) | 0.990 | 1.068 | (0.838–1.362) | 0.5946 |

| Income Level | ||||||

| Low | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Middle-Low | 1.461 | (0.793–2.689) | 0.224 | 1.337 | (0.957–1.868) | 0.0892 |

| Middle-High | 1.142 | (0.612–2.130) | 0.678 | 1.537 | (1.057–2.234) | 0.0244 |

| High | 1.286 | (0.680–2.429) | 0.439 | 1.782 | (1.192–2.663) | 0.0049 |

| Current economic activity | ||||||

| No | 0.985 | (0.606–1.602) | 0.953 | 0.571 | (0.372–0.878) | 0.0108 |

| Yes | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Health insurance | ||||||

| Medical aid | 1.661 | (0.799–3.452) | 0.174 | 1.438 | (0.876–2.362) | 0.1507 |

| National Health insurance | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Never | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Former smoker | 1.470 | (0.673–3.209) | 0.334 | 1.106 | (0.613–1.996) | 0.7384 |

| Smoker | 1.057 | (0.400–2.793) | 0.911 | 0.973 | (0.459–2.065) | 0.9438 |

| Alcohol status | ||||||

| Never | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Former drinker | 1.419 | (0.654–3.081) | 0.376 | 1.121 | (0.574–2.189) | 0.7379 |

| Drinker | 0.583 | (0.251–1.354) | 0.210 | 1.315 | (0.572–3.025) | 0.5187 |

| Number of chronic diseases† | ||||||

| 0 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| 1 | 1.334 | (0.887–2.005) | 0.166 | 1.210 | (0.906–1.618) | 0.197 |

| 2 | 1.526 | (0.920–2.533) | 0.102 | 1.320 | (0.938–1.857) | 0.1116 |

| ≥ 3 | 1.615 | (0.834–3.125) | 0.155 | 1.398 | (0.921–2.123) | 0.1155 |

Model 1 was adjusted with participants who under 64 years.

Model 2 was adjusted with participants who over 65 years.

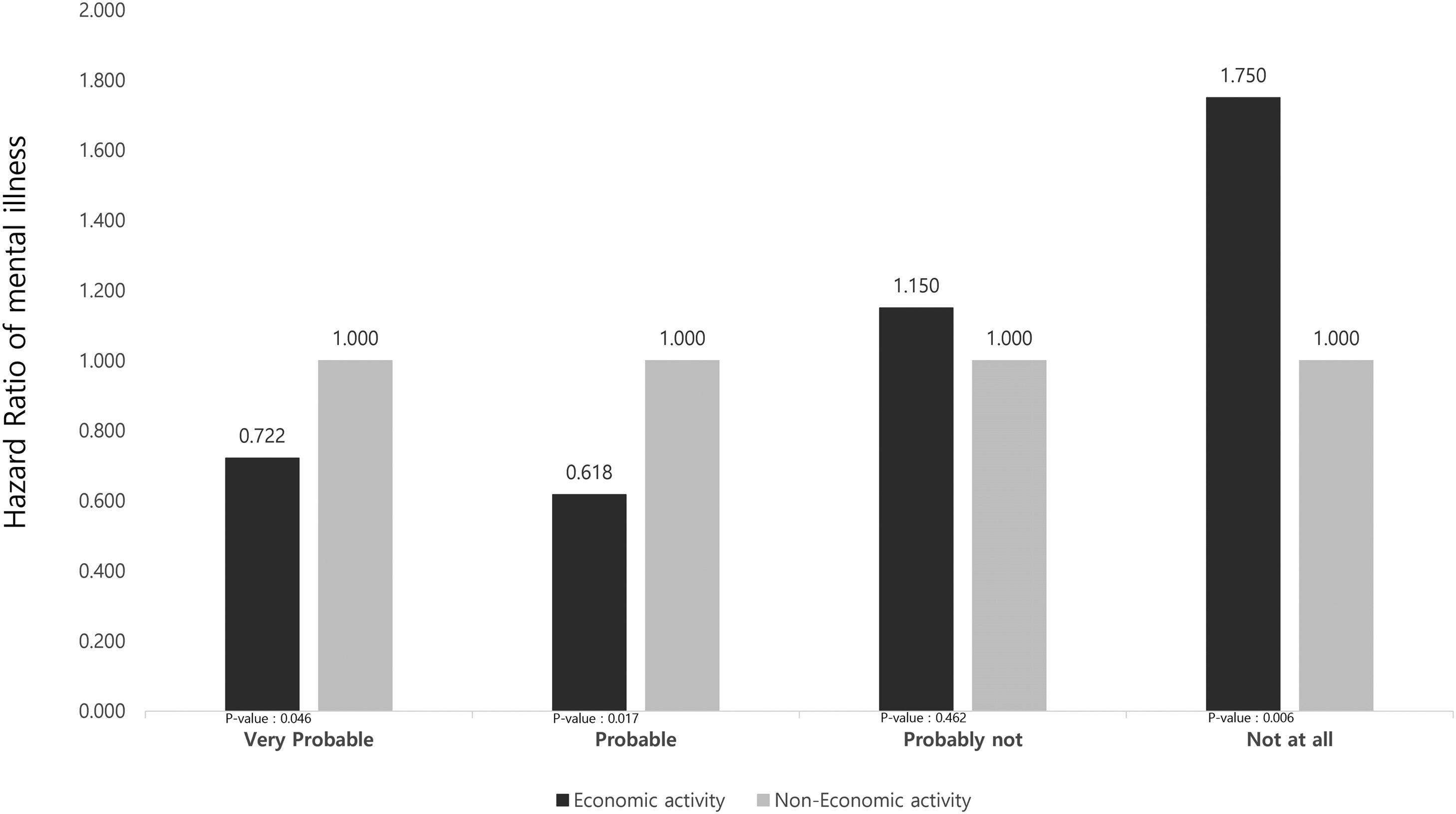

Fig. 3 shows the results of the subgroup analysis stratified by current economic activity.

In terms of the ‘Very probable’ or ‘Probable’ groups, compared to the non-EA, EA group had a lower mental illness rate of 0.722 times (HR: 0.722, 95 % CI: 0.531 – 0.992, P-value: 0.046), 0.618 times (HR: 0.618, 95 % CI: 0.458 – 0.831, P-value: 0.017) respectively. Meanwhile, in terms of the ‘Probable not’ or ‘Not at all’ groups, EA group had a high incidence of mental illness rate compared to non-EA group respectively (HR: 1.150, 95 % CI: 0.793 – 1.667 P-value: 0.462; HR: 1.750, 95 % CI: 1.166 – 2.625, P-value: 0.00).

DiscussionWhile the proportion of the elderly in Korea is predicted to increase rapidly,25 the EAR rate of the middle-aged and elderly was 15.7 %.7 Due to this situation, various studies are being conducted on the relationship between EA and health.26,27 This study aims to identify the relationship between EAR and mental illness by using the 1st–8th KLoSA.

The results are summarized as follows. The group experiencing the strongest EAR had a higher incidence of mental illness than those without EAR. As a result of stratified age analysis, there was no relationship between EAR and mental illness in the elderly. However, among middle-aged adults, the higher the intensity of EAR, the higher the incidence of mental illness.

According to a previous study in Korea,28 analysis of the association between EAR and mental health among 8150 adults showed that the EAR group had a higher experience of depression (Odds Ratio [OR]: 3.30) and experience of stress (OR: 2.69) compared to the non-EAR group. This is because, compared to the non-EAR group, which lead to a more energetic lifestyle by forming bonds with others through smooth EA, the group with EAR had reduced confidence and efficacy, as well as the activity levels necessary to maintain a basic lifestyle, resulting in a decrease in overall mental health. This happens because their health has deteriorated.28 In addition, in the results of a previous study that analysed the association between EAR and cognitive function for middle-aged and elderly people aged 45 and over in Korea,29 the group with the highest intensity of EAR not only had an MMSE score 0.12 points lower than that of the group without EAR, but it also had a 2.58 OR higher incidence of cognitive dysfunction.

According to Hultsch's ‘Use it or lose it’ hypothesis,30 an individual's cognitive function can be maintained or deteriorated depending on how cognitively active an individual stay. It has been revealed that when people experience EAR due to their health status, they are failure to stay cognitively active, accelerating cognitive decline and the risk of dementia.30 In addition, as many previous studies suggest that EAR can be a factor in the occurrence of potential mental disorders,31-33 the results of this study show that the incidence of mental illness increases as people experience EAR, which is consistent with previous studies.28-33

In addition, the results of this study also agreed with previous studies that the higher the EAR, the higher the incidence of mental illness in the middle-aged group under 64 years, unlike the elderly group over 65 years of age.28,34 As middle-aged Koreans are more economically active than the elderly, they are at the peak of their socioeconomic status. At the same time, the burden of double support for both parents and children is at its greatest, so the overall importance and necessity of economic activities for this group is very high.28,34 In fact, further analysis results, Within the group exhibiting high levels of EAR, the incidence of mental illness was lower compared to the non-economic activity group. However, The group with EAR due to health conditions may face not only limitations in EA but also potential constraints in daily life activities.35 This could lead to reduced social cohesion, increased social isolation, and other health issues, which in turn might contribute to both worsened health conditions and an increased risk of developing mental illness.29,36,37

Due to these cultural characteristics of Korea, it was found that the more severe the EAR of middle-aged people, the worse the mental health and mental illness that occur. In particular, a previous study in Korea analysed the relationship between EAR and mental health among 5049 middle-aged people and found that the higher the intensity of EAR, the higher the rates of depression were by 3.613 points, leading to suicide.38 In the case of other previous studies,39 the MMSE score decreased by 0.41 points in the group with the sustained in unemployment in middle-aged adults, and the CES-D score increased by 0.56 points. Also, in a previous study in the United States, as a result of following up on the main causes of depression in 9747 middle-aged people, it was reported that socioeconomic restrictions have a strong effect on the onset and aggravation of depression.40

However, in previous European studies,41,42 if a job suitable for an individual's health level is linked to the middle-aged and elderly group whose work life is unstable due to EAR, or EA opportunities are provided to the unemployed group, it is revealed that not only is subjective health status improved, but positive effects can also be obtained in mental health areas such as stress and depression. Therefore, the proposed approaches tailored to the Korean context are as follow. Recently, Korean health authorities have been implementing support programs aimed at engaging the EAR group in community activities (Religious gathering, Fellowship gathering, Leisure etc.).43 In fact, through participation in such community activity programs, improvements in mental health levels and quality of life have been reported.43 Furthermore, there has been an expansion of mental health services at the community level targeting groups such as the EAR group and the unemployed. This expansion has resulted in reported reductions in mental disorders and suicide rates.44 However, the utilization rate of mental health services in Korea is overall lower, at 17.5 %, compared to 32.9 % in the United States. Not only that, but mental health programs are also disproportionately concentrated in urban areas.45 Furthermore, even in the ‘Health plan 2030’, a decade-long plan developed by Korean health authorities, there is no inclusion of mental health programs specifically targeting this group.46

Therefore, based on the results of this study, it is necessary to provide a community activities participation policy or policies for improved access to mental health services to prevent mental health deterioration and the incidence of mental illness in the EAR group. Specifically, if a specific mental health promotion program is developed and provided for middle-aged Koreans, it may be possible to prevent the incidence of mental illness among middle-aged Koreans who are experiencing EAR.

This study has various strengths, particularly with its use of a population-based representative sample and 15-year follow-up database. In addition, it advances knowledge on restricted economic or productive activities in Korea. It also used large nationally representative longitudinal survey data from a well-defined and comprehensively studied sample of middle-aged and elderly adults. These data were analysed to study the association between EAR and mental illness to improve the generalizability of our results. Also, we used multivariable time-dependent Cox regression modeling to adjust for confounders in the present study. Nevertheless, our study has several limitations as well. First, this study had a subjective bias due to the KLoSA used in the analysis, mixed with the respondents’ opinions. Second, it analysed longitudinal data, but the results may reflect an inverse causal relationship between the EAR and mental illness. Finally, the key variable utilized in this study, “EAR due to health condition,” is based on the GALI indicator, which is employed in surveys,23 such as the European Health Interview Survey (EHIS), Survey on Income and Living Conditions (SILC), and the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). However, it is important to recognize the limitations stemming from its nature as a single-item measure involving subjective opinions. These limitations should be understood and considered when interpreting the research findings.

ConclusionThe group who experienced EAR due to health condition had a higher incidence of mental illness than the non-EAR. Moreover, as a result of a detailed analysis by stratification of age, the incidence of mental illness increased as the intensity of EAR increased in the middle-aged population. Also, among the group experiencing EAR, the incidence of mental illness was lower in the EA group compared to the non-EA. Therefore, if we provide opportunities to participate in community activities or provide the mental health promotion programs for middle-aged population who are experiencing EAR due to health condition, it is expected to prevent the deterioration of mental health and reduce the incidence of mental illness among the middle-aged Korean population.

Author contributionsJeong Min Yang designed this study, performed statistical analysis, drafted and completed the manuscript. Jae Hyun Kim conceived, designed and directed this study.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

FundingNone.

Data availability statementThe data supporting the findings of this study are openly available at https://survey.keis.or.kr/eng/klosa/klosa01.jsp.