Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is characterized by cognitive dysfunction and neurotropic and inflammatory factors linked to its pathophysiology and cognitive impairment. This study aims to identify the prodromal serum biomarkers correlated to cognitive impairment in individuals diagnosed with MDD, including variation between sexes.

MethodsThis study is part of a larger two-stage research. The initial stage involved the sample of participants aged between 18 and 60 years old, diagnosed with MDD. The second phase took place three years later. The baseline assessments included a biomarker blood test (BDNF, GDNF, NGF, IL-6 and TNF-α). Follow-up assessments used the Cognitive Complaints in Bipolar Disorder Rating Assessment (COBRA) for subjective cognition and the number-letter sequence of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-III) for objective cognition.

ResultsThe sample consisted of 155 subjects, 30 males and 125 females. In the sex-stratified sample, a correlation was found between COBRA and GDNF biomarkers in males (r= -0.339; p = 0.039). When COBRA was applied as a dependent variable in the multiple linear regression, the overall model was significant (Z (9, 50) = 2.611, p = 0.032; adjusted R2 = 0.620), with the highest impact on sex (β = 0.442, p = 0.003, padjFDR = 0.019), symptom severity (β = 0.605, p < 0.001, padjFDR = 0.013) and GDNF levels (β = -0.414, p = 0.005, padjFDR = 0.021).

ConclusionsOur results suggest that GDNF might be a prodromal biomarker for the early detection of subjective cognitive complaints only when targeting males with MDD.

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is the psychiatric disorder with the highest worldwide prevalence, impacting approximately 5 % to 6 % of the population and representing a significant contributor to disability, morbidity, and mortality.1 Through a lifespan, depression is twice as prevalent in women when compared to men, reaching its highest peak during the second and third decades of one's life.2 Considering this, there is a research gap in understanding this sex disparity, prompting speculation if this difference might be linked to the pathophysiology of MDD. An emerging discussion in academia is surging where more studies are attempting to connect depression pathogenesis with the inflammatory and neurotrophic systems.

A possible contributor is the pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as Interleukin 6 (IL-6) and Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-α). Responsible for triggering several signalling pathways that can induce alterations in monoamine levels, increasing neural excitotoxicity, impairing auto-regulatory endocrine pathways and reducing neurotrophins.3 As a consequence of the inflammatory stimuli, oxygen and nitrogen species are released, which may contribute to depression by promoting brain excitotoxicity and suppressing neurogenesis, reducing protective factors such as neurotrophins.4 Some studies highlight sex differences between the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in individuals with MDD. A current debate in research is that the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines are responsible for the incidence of MDD being higher in females, due to some studies observing a higher immune response in males.5,6

An additional potential contributor is neurotrophins, including Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), Nerve Growth Factor (NGF) and Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (GDNF). Neurotrophins play an important role in cell proliferation, maintaining migration during the development of the central nervous system (CNS), thus ensuring the structural integrity of neurons, and promoting neurogenesis.7,8 8 Some studies provided results where individuals with lower peripheral concentrations of neurotrophins are correlated with MDD diagnosis,9 and in addition, they are also associated with lower performances in cognitive tests.10 As a conclusion to these results, the literature suggests that females with MDD may exhibit lower levels of NGF and BDNF compared to males.11,12 Although, controversial findings were found where males diagnosed with MDD have also been found with decreased levels of GDNF,13 and other studies found no differences in neurotrophin levels between sexes.14,15

Another important factor is the relationship between cognitive dysfunction and biomarkers. Cognitive dysfunction stands as a core consequence of MDD, where individuals often exhibit progressive cognitive impairment that may persist even after the disorder has been remitted.16 It is observed in the literature that the relationship between cognitive impairments tends to positively correlate to pro-inflammatory cytokines, and negatively to neurotrophins in both healthy individuals and those diagnosed with MDD.17,18 Therefore, research indicates that the relationship between cognitive function and immune systems differs between sexes, suggesting that IL619 and TNF-a20 could be associated with cognitive impairment in females.

However, this suggestion is controversial since a portion of the literature did not observe a difference between sexes and increased levels of cytokines and there is an absence of studies associating neurotrophins with cognition while stratifying the sample relating to sex.21 Therefore, additional research is needed to address this gap.

In light of this, there is a lack of consensus on the importance of the peripheral changes in sex-linked biomarkers within biological processes associated with MDD. The novel biomarkers for MDD hold significance for the development of diagnosis and the characterization of MDD-associated features, such as cognitive impairment. In this context, the search for prodromal biomarkers becomes crucial, given the substantial correlation between cognitive deficits in individuals with MDD. Potentially providing new tools to diagnose and prevent the progression of this disorder7 Thus, the present study aims to identify prodromal serum biomarkers correlated with cognition in patients with MDD, as well as the possible sex-related differences.

Materials and methodsParticipantsThis study was derived from a broader prospective study, previously published.8 The initial phase of the study included 585 participants diagnosed with MDD, aged between 18 and 60 years. It was carried out at the Outpatient Clinic for Research and Extension in Mental Health of the Catholic University of Pelotas (UCPel), from 2012 to 2015. The subsequent stage of the study took place between 2017 and 2018, approximately 3 years following the first stage.

All participants who agreed to participate in the study signed an informed consent form and, when deemed necessary, were referred to appropriate treatment options. Exclusion criteria included participants unable to comprehend the utilized instruments and those who declined blood collection during the initial stage. Additionally, individuals who failed to respond to the Cognitive Complaints in Bipolar Disorder Rating Assessment (COBRA) in the second stage were excluded. Thus, this article presented a final sample of 155 participants.

InstrumentsDuring the initial phase of the study, sociodemographic data were collected from the sample (sex, age, years of education, socioeconomic status) according to the Brazilian Association of Research Companies (ABEP).22 The ABEP classification is grounded in the material possessions and educational background of the family head. This classification employs an economic class scale (A, B, C, D, and E), where "A" denotes a higher economic class and "E" denotes a lower economic class. For analytical purposes, this variable was categorized into high class (A/B) and low class (C/D/E).

To assess the current use of psychiatric medications, self-report questionnaires were used. To assess alcohol and tobacco abuse or dependence, the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) was used. Scores above 4 points were considered as abuse/dependence in this study.23

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview Plus (MINI-Plus)24 was used for the diagnosis of MDD. In addition, the diagnosis was substantiated through a clinical interview conducted by qualified and trained psychologists, acknowledged as the gold standard in this assessment category. In instances where uncertainty regarding the diagnosis arose, patients went through reassessment with an experienced psychiatrist to either confirm or refute the initial diagnosis.

To evaluate depressive symptoms, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) was applied. This is a 21-item multiple-choice self-report inventory designed to measure the severity of depression. The total score ranges from 0 to 63 points and enables the classification of symptom severity. A higher score indicates a greater manifestation of depressive symptoms.25 The scale also classifies the severity according to the score obtained. For the present article, subjects scoring between 0 and 13 were categorized as euthymic, while those with scores above 14 were considered to be experiencing a depressive episode.

In the second stage of assessment, participants responded to the COBRA instrument, valid for use in Brazil.26 The version utilized in this study included 16 items, evaluating subjective cognitive dysfunctions through self-report, and assessing domains such as executive function, processing speed, working memory, verbal learning and memory, attention/concentration and mental tracking.27 Notably, none of the items are exclusively directed towards bipolar disorder. COBRA employs a 4-point scale for each item, with scores ranging from 0 to 48. A higher individual score indicates a greater expression of subjective cognitive complaints.26

Objective cognitive performance was evaluated through the Sequence of Numbers and Letters of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-III), referred to as a number-letter sequence in the text. This subtest assesses memory and attention domains, including working memory, mental manipulation, attention, concentration, and short-term auditory memory. Comprising seven items, each with three attempts, the total score ranges from 0 to 21 points, with higher scores indicating superior cognitive performance.28

Biochemical analysisOnly in the first stage of the study, venous blood collection was performed. This procedure involved the venipuncture of 10 mL of blood, drawn into a vacuum tube devoid of anticoagulants, subsequent to the patient interview, and occurred between 8:00 am and 11:00 am. Post-collection, the blood was immediately centrifuged at 4000 g for 10 min. The resultant serum was segregated into microtubes and stored at −80 °C until analysis.

For the measurement of serum levels of IL-6, TNF-α, BDNF, GDNF and NGF, a commercial immunoassay kit was used (DuoSet ELISA Development, R&D Systems, Inc., EUA). Serum levels of IL-6, TNF-α, GDNF and NGF were expressed in pg/mL, whereas BDNF levels were expressed in ng/mL.

Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were performed using SPSS 27.0 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, EUA) and GRAPHPAD PRISM 6.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, EUA). To assess the differences between the groups concerning clinical and sociodemographic characteristics analyses were performed using the Mann-Whitney and Spearman correlation tests, as the serum levels of IL-6, TNF-a; BDNF; GDNF and NGF, as well as the COBRA scores did not show a parametric distribution. Data was presented by median and 25/75 interquartile range, and Spearman's correlation coefficient.

Since the COBRA, number-letter sequence (objective cognition) and GDNF data did not have a normal distribution, to carry out the multiple linear regression, these findings were normalized using the square-root transformation (sqr).

A multiple linear regression analysis (enter method) was carried out based on a conceptual model with three hierarchical levels: sociodemographic predictors (gender, age, socioeconomic status), clinical predictors (alcohol and tobacco abuse and dependence; use of psychiatric medication; depressive symptoms) and biomarkers (IL-6; TNF-a; BDNF; GDNF and NGF). The model was used to investigate to which extent the baseline results of the study had an impact on objective (sequence of numbers and letters) and subjective (COBRA) cognitive complaints at the follow-up. Multiple linear regression was performed for each dependent variable and to adjust for multiple testing, the p-values were corrected using a false discovery rate correction (FDR, the Benjamini-Hochberg method).

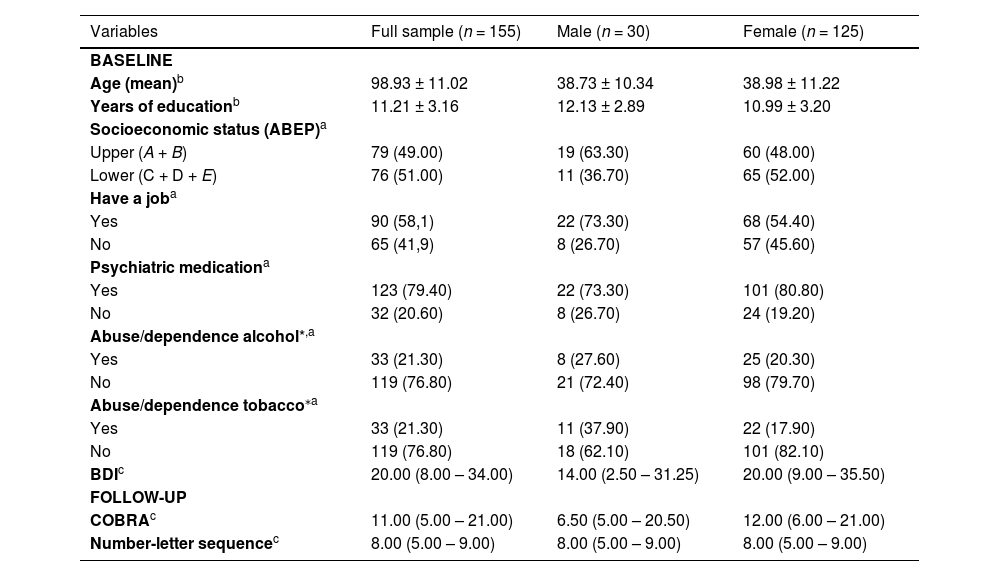

ResultsThe total study sample consisted of 155 participants, initially diagnosed with MDD, who were stratified into two groups based on sex, 30 males and 125 females (Fig. 1). In the total sample, 79.40 % of individuals were on psychiatric medication, 21.30 % reported alcohol abuse/dependence, and 21.30 % tobacco abuse/dependence. The median and interquartile range of the severity of depressive symptoms, assessed by the BDI in the total sample, were 20.00 (8.00 - 34.00).

In the sex-stratified sample, the use of psychiatric medication in the male subgroup was 73.30 %, alcohol abuse/dependence was 27.60 %, and tobacco abuse/dependence was 37.90 %. In the female subgroup, 80.80 % used psychiatric medication, 20.30 % reported alcohol abuse/dependence, and 17.90 % tobacco abuse/dependence. The median and interquartile range of the severity of depressive symptoms in the male subgroup was 14.00 (2.50 - 31.25), while in the female subgroup, it was 20.00 (9.00 - 35.50). Table 1 shows other sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the total and stratified sample by sex. No statistically significant association was found when COBRA was related to sociodemographic variables (data not shown).

Clinical and socio-demographic characteristics of sample at baseline.

| Variables | Full sample (n = 155) | Male (n = 30) | Female (n = 125) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BASELINE | |||

| Age (mean)b | 98.93 ± 11.02 | 38.73 ± 10.34 | 38.98 ± 11.22 |

| Years of educationb | 11.21 ± 3.16 | 12.13 ± 2.89 | 10.99 ± 3.20 |

| Socioeconomic status (ABEP)a | |||

| Upper (A + B) | 79 (49.00) | 19 (63.30) | 60 (48.00) |

| Lower (C + D + E) | 76 (51.00) | 11 (36.70) | 65 (52.00) |

| Have a joba | |||

| Yes | 90 (58,1) | 22 (73.30) | 68 (54.40) |

| No | 65 (41,9) | 8 (26.70) | 57 (45.60) |

| Psychiatric medicationa | |||

| Yes | 123 (79.40) | 22 (73.30) | 101 (80.80) |

| No | 32 (20.60) | 8 (26.70) | 24 (19.20) |

| Abuse/dependence alcohol*,a | |||

| Yes | 33 (21.30) | 8 (27.60) | 25 (20.30) |

| No | 119 (76.80) | 21 (72.40) | 98 (79.70) |

| Abuse/dependence tobacco⁎a | |||

| Yes | 33 (21.30) | 11 (37.90) | 22 (17.90) |

| No | 119 (76.80) | 18 (62.10) | 101 (82.10) |

| BDIc | 20.00 (8.00 – 34.00) | 14.00 (2.50 – 31.25) | 20.00 (9.00 – 35.50) |

| FOLLOW-UP | |||

| COBRAc | 11.00 (5.00 – 21.00) | 6.50 (5.00 – 20.50) | 12.00 (6.00 – 21.00) |

| Number-letter sequencec | 8.00 (5.00 – 9.00) | 8.00 (5.00 – 9.00) | 8.00 (5.00 – 9.00) |

ABEP, Brazilian Association of Research Companies; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; COBRA, Cognitive Complaints in Bipolar Disorder Rating Assessment; WAIS- III, Sequence of Numbers and Letters of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale.

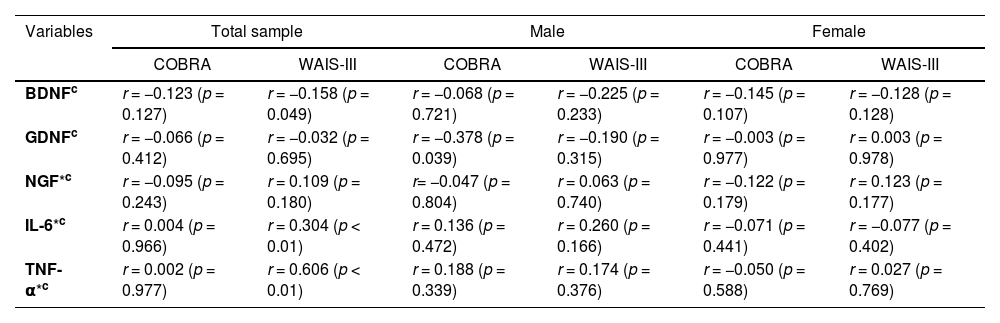

No significant results were observed between the correlation of serum biomarkers and number-letter sequence (p > 0.05) in any of the subgroups (Table 2). However, a negative correlation was observed between COBRA and serum levels of GDNF (r= −0.339; p = 0.039) in the males (Fig. 2B), but not in the female group (r = 0.003; p = 0.977) (Fig. 2C).

Correlation between serum levels of biomarkers at baseline with subjective cognitive function (COBRA) and objective cognitive function (WAIS-III) at the follow-up.

| Variables | Total sample | Male | Female | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COBRA | WAIS-III | COBRA | WAIS-III | COBRA | WAIS-III | |

| BDNFc | r = −0.123 (p = 0.127) | r = −0.158 (p = 0.049) | r = −0.068 (p = 0.721) | r = −0.225 (p = 0.233) | r = −0.145 (p = 0.107) | r = −0.128 (p = 0.128) |

| GDNFc | r = −0.066 (p = 0.412) | r = −0.032 (p = 0.695) | r = −0.378 (p = 0.039) | r = −0.190 (p = 0.315) | r = −0.003 (p = 0.977) | r = 0.003 (p = 0.978) |

| NGF*c | r = −0.095 (p = 0.243) | r = 0.109 (p = 0.180) | r= −0.047 (p = 0.804) | r = 0.063 (p = 0.740) | r = −0.122 (p = 0.179) | r = 0.123 (p = 0.177) |

| IL-6*c | r = 0.004 (p = 0.966) | r = 0.304 (p < 0.01) | r = 0.136 (p = 0.472) | r = 0.260 (p = 0.166) | r = −0.071 (p = 0.441) | r = −0.077 (p = 0.402) |

| TNF-α*c | r = 0.002 (p = 0.977) | r = 0.606 (p < 0.01) | r = 0.188 (p = 0.339) | r = 0.174 (p = 0.376) | r = −0.050 (p = 0.588) | r = 0.027 (p = 0.769) |

Variable contains missing data

COBRA, Cognitive Complaints in Bipolar Disorder Rating Assessment; WAIS-III, number-letter sequence of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; GDNF, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor; NGF, nerve growth factor; IL-6, interleukin 6, TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

Correlation between serum GDNF levels in baseline and COBRA scores at follow-up. A) Correlation between serum GDNF levels and COBRA in total sample r= −0.052 (p = 0.485); B) Correlation between serum GDNF levels and COBRA in males r= −0.378 (p = 0.032); C) Correlation between serum GDNF levels and COBRA in females r = 0.003 (p = 0.977).

In addition, a correlation was made between the severity of symptoms, assessed using the BDI, and cognitive performance measured by the number-letter sequence and COBRA. No correlation was observed between the BDI and the number-letter sequence (objective cognition), either in the total sample or when stratified by sex (data not shown). However, when BDI was correlated with COBRA, a significant correlation was observed in the total sample (r = 0.761; p < 0,001), as well as in the subgroups, males (r = 0.700; p < 0.001) and females (r = 0.769; p < 0.001).

Furthermore, a correlation analysis was conducted between the two tools assessing subjective and objective cognitive function (COBRA and number-letter sequence) to evaluate potential discrepancies between scores. The results revealed no significant correlation between COBRA and number-letter sequence in the total sample (r = −0.057; p = 0.484), as well as in the male (r = 0.172; p = 0.362) and female (r = −0.110; p = 0.220) subgroups.

Consecutively, Table 2 shows the correlation within the total sample and is further stratified by sex, depicting serum biomarker levels (BDNF, GDNF, NGF, IL-6 and TNF-α) at baseline with subjective and objective cognitive measurement scales (COBRA and number-letter sequence, respectively) in the follow-up. No significant correlation was observed in the total sample between biomarkers and COBRA variables. However, a correlation was found significant in the total sample between number-letter sequence and the biomarkers BDNF (r = −0.158; p = 0.049), IL-6 (r = 0.304; p < 0.01), and TNF-α (r = 0.606; p < 0.01).

The multiple linear regression that used the number-letter sequence as the dependent variable showed that the overall model was not significant (Z (8, 49) = 0.849, p = 0.565; adjusted R2 = 0.122) (data not shown).

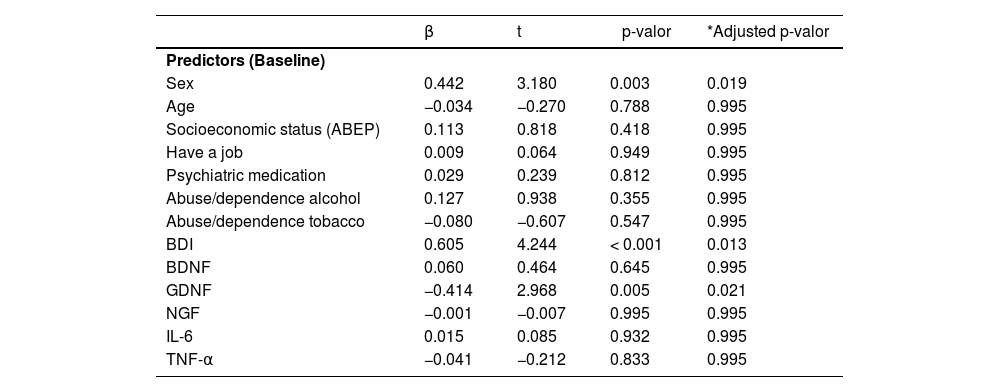

When COBRA was used as the dependent variable, the results showed that the overall model was significant (Z (9, 50) = 2.611, p = 0.032; adjusted R2 = 0.620). Table 3 shows the impact of the coefficients for all the predictors analyzed. As can be seen, the variables that most strongly impact COBRA were sex (β = 0.442, p = 0.003, padjFDR = 0.019), symptom severity (β = 0.605, p < 0.001, padjFDR = 0.013) and GDNF levels (β = - 0.414, p = 0.005, padjFDR = 0.021).

Summary of multiple regression analyses for variables predicting COBRA.

| β | t | p-valor | *Adjusted p-valor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors (Baseline) | ||||

| Sex | 0.442 | 3.180 | 0.003 | 0.019 |

| Age | −0.034 | −0.270 | 0.788 | 0.995 |

| Socioeconomic status (ABEP) | 0.113 | 0.818 | 0.418 | 0.995 |

| Have a job | 0.009 | 0.064 | 0.949 | 0.995 |

| Psychiatric medication | 0.029 | 0.239 | 0.812 | 0.995 |

| Abuse/dependence alcohol | 0.127 | 0.938 | 0.355 | 0.995 |

| Abuse/dependence tobacco | −0.080 | −0.607 | 0.547 | 0.995 |

| BDI | 0.605 | 4.244 | < 0.001 | 0.013 |

| BDNF | 0.060 | 0.464 | 0.645 | 0.995 |

| GDNF | −0.414 | 2.968 | 0.005 | 0.021 |

| NGF | −0.001 | −0.007 | 0.995 | 0.995 |

| IL-6 | 0.015 | 0.085 | 0.932 | 0.995 |

| TNF-α | −0.041 | −0.212 | 0.833 | 0.995 |

COBRA, Cognitive Complaints in Bipolar Disorder Rating Assessment; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; GDNF, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor; NGF, nerve growth factor; IL-6, interleukin 6, TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

This study aimed to identify prodromal serum biomarkers correlated with cognition in patients with MDD. Our findings indicate that, among the evaluated biomarkers (IL-6, TNF-α, BDNF, GDNF, NGF), only GDNF may be suggested as a prodromal biomarker. However, only for subjective cognitive complaints, and specifically in males with MDD. This suggestion is based on the observed findings, where lower serum levels of GDNF at baseline were associated with higher COBRA scores in the male subgroup during follow-up assessments. In addition, we also observed an association between the severity of depressive symptoms and the subjective assessment of cognition, both in the total sample and stratified by sex.

Our initial hypothesis was that a reduction in serum neurotrophin levels, and an increase in serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines at baseline, could serve as predictors of cognitive deficits in the follow-up assessments. Previous studies have indeed demonstrated the role of decreased neurotrophin levels (BDNF, GDNF and NGF)9,11, and increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and TNF-α)29 in subjects with MDD. Neurotrophins also seem to have a relationship with cognitive dysfunction in existing literature, where a recent meta-analysis showed that these molecules appear to reduce in subjects exhibiting cognitive deficits.7 In addition, a potential association between decreased serum neurotrophin levels and complaints about cognitive performance, especially in memory and attention domains, which is plausible.7 Identifying serum neurotrophin levels as potential prodromal biomarkers of cognitive deficits in individuals with MDD is promising for improving our understanding of the disorder and could contribute to the future development of specific interventions. 30

In our study, we found that GDNF, sex, and BDI were associated with COBRA (subjective cognition). After stratifying the sample by sex, we observed a negative correlation only between the GDNF biomarker and COBRA in the male group. The BDI showed a correlation both in the total sample and in stratified subgroups.

Our study seems to be the first to longitudinally evaluate the correlation between neurotrophins, pro-inflammatory cytokines and cognitive impairment in a sample of subjects with MDD, considering the potential differences between the sexes. The evaluation of biomarkers through stratification by sex is of paramount importance, as it helps to determine whether any biomarker is associated with sex. Although the literature demonstrates that depression is more prevalent among females, the differences in the responses of males and females to biological processes linked to MDD, such as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, inflammatory response, and neurotrophic dysregulation have not yet been clarified. Furthermore, there is no consistent evidence to explain why MDD is more prevalent in females.5,6

When looking at the influence of sex on biomarkers, some studies have suggested that inflammatory markers are more associated with males with MDD, as males may be more predisposed to an inflammatory state than females.5,6 This could be attributed to testosterone's ability to suppress the immune system in males, while estrogens strengthen the immune system in females.5,31 Additionally, genetic differences may also play a role, once immunological factors are linked to the X chromosome. Since females have double X chromosomes, they might have a more immunocompetent system.31

BDNF and NGF levels are reported to be lower in females with MDD compared to males with MDD.11,12 However, GDNF tends to be decreased in the group of males with MDD, once compared to the females diagnosed with MDD subgroup.13 Although, the mechanisms responsible for these sex differences remain unknown and existing results are contradictory in many cases. Despite this, studies evaluating these neurotrophins, cognition, and the difference between the sexes, are currently scarce.

Furthermore, in our study, we observed that GDNF could serve as a prodromal biomarker for subjective cognitive complaints in the male group, rather than for objective cognitive measures. Although previous studies have identified differences between subjective and objective assessments32,33, none have compared the subjective COBRA scale and objective number-letter sequence subscale until our current study.

The differences between subjective and objective measures observed in our study might be explained due to the challenge of correlating self-report cognitive symptoms with objectively assessed cognitive dysfunction. Typically, individuals tend to overreport cognition complaints when self-reporting.34 Although, these subjective complaints may be viable as predictors of future cognitive impairments that might be evident in the objective evaluation. And therefore highlighting the importance of early intervention prior to apparent cognitive impairment. This could explain the lack of correlation between neurotrophins and number-letter sequence cognitive subscale scores. However, it is important to note that in our study, we exclusively utilized the number-letter sequence from the WAIS-III, which specifically assesses memory and attention domains. This is in contrast to the COBRA, which encompasses a broader range of cognitive functions. In this context, the absence of a correlation between COBRA and the number-letter sequence may be attributed to the possibility that patients might have deficits in other cognitive domains assessed solely by COBRA, not covered by the number-letter sequence.

In our study, we observed an association between GDNF and subjective cognitive complaints exclusively in males. This discovery prompts further investigations into potential future cognitive deficits and the development of preventive measures against cognitive impairment in males diagnosed with MDD. However, our findings, which link reduced serum GDNF levels only in males and subjective cognitive measure, are different from other results in the literature. In published articles, this relationship is observed in the total sample and is found in objective measures of cognition. Zhang et al. (2014) observed a correlation between reduced GDNF levels and objectively assessed cognitive decline, using the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), in the total sample with MDD.18 Other studies showed a negative correlation between serum GDNF levels and executive function, using WCST, in the total sample of subjects with anorexia nervosa, when compared with healthy controls.35 In addition, a study found that repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation improved depressive and cognitive symptoms in treatment-resistant depression subjects, as well as increased serum GDNF levels.36

The potential association between GDNF and cognition may stem from its ability to regulate neuronal and glial plasticity, as well as protect neural cells from oxidative stress.37 A study conducted on mice with a deletion of the GDNF gene (GDNF+/−) observed reduced GDNF mRNA and, consequently, spatial memory impairment.38 Furthermore, overexpression of GDNF in hippocampal dorsal astrocytes CA1 has been linked to improved spatial learning and memory performance in elderly rats with cognitive impairment, as it enhances local cholinergic, dopaminergic, and serotonergic transmission.39 These findings in the literature lead us to hypothesize that decreased levels of GDNF may diminish neuroprotection, rendering neurons susceptible to oxidative and immune damage, and disrupting neuronal and glial plasticity, thereby affecting cognition in individuals with MDD. To the present moment, our study is the first to find data that supports that cognitive impairment in MDD, linked to a decrease in serum GDNF levels, is exclusive to males.

Finally, our study revealed an association between the severity of depressive symptoms, evaluated through the BDI, and COBRA, and a correlation in the total sample, in male and female subgroups independently. Other studies also corroborate our findings, noting a direct association between subjective cognitive complaints assessed through COBRA and depressive symptoms.40 Additionally, they indicate an indirect association between these complaints and the perception of overall health through depressive symptoms in Japanese adult volunteers.40 The same research group also observed a significant correlation between cognitive complaints, work limitations, and depressive symptoms in Japanese adult workers.41 In addition, subsyndromal depression, brief depressive episodes, and depressive episodes were significantly associated with higher mean subjective cognitive complaints scores in all age groups, and both males and females.42

As with any research, we acknowledge the limitations of our study. First, we had a small sample size, particularly when stratified by sex, this may contribute to type II statistical error during analyses. Secondly, regarding the study design, although individuals with the highest depressive scores exhibited the highest subjective cognitive deficits in the follow-up, we cannot confirm a correlation since these symptoms were not assessed again during second phase of the study. Lastly, we only measured the levels of potential biomarkers at baseline. Correspondingly, cognition was evaluated at a single time point, restricting our ability to establish causality between variables. However, our study was the first to assess predictors of subjective cognitive complaints in subjects with MDD, while also stratifying the sample by sex. Thus facilitates future studies to further investigate and validate our findings, contributing to the understanding of predictive biomarkers that assist in clinical diagnosis.

ConclusionOur findings show a negative correlation between serum GDNF levels and subjective cognitive complaint scores (COBRA), only in males diagnosed with MDD. While this is not backed by current literature, it is an important finding that further supplements the content of this research matter. Future studies are needed to confirm the role of GDNF as a prodromal biomarker for subjective cognitive complaints in males.