Supporting the neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia, minor physical anomalies (MPAs) are markers of abnormalities in early fetal development. The mouth seems to be a common region for the occurrence of MPAs in patients with schizophrenia. This study aimed to compare the palatal rugae patterns, according to their length, shape, and orientation, between patients with schizophrenia and controls in a blinded fashion. The palatal rugae patterns were also evaluated by sex, as its effect on neurodevelopment was relevant.

MethodsDental stone models were fabricated from maxilla impressions of patients with schizophrenia (N = 105) and controls (N = 105). Based on their lengths, three types of palatal rugae were classified; primary, secondary, and fragmentary. Primary rugae were further categorized according to their shape and direction.

ResultsThe most detected palatal rugae were the primary ones in both groups. The primary, secondary, and fragmentary rugae numbers in both groups were no different. There were significant differences in the shape and orientation of the primary rugae between the two groups. Curved (OR:1.76, p = 0.006), island (OR:2.97, p = 0.001) and nonspecific (OR:5.44, p = 0.004) primary rugae shape were found to be significant predictive variables for schizophrenia. Randomly oriented rugae numbers were higher in schizophrenics than controls (p = 0.018). The two sexes had different preferences in primary rugae shapes and directions compared to same-sex controls in patients with schizophrenia.

ConclusionIdentifying subtle changes in the primary rugae pattern, which appear to be sex-specific, is consistent with impaired neurodevelopment in schizophrenia.

Minor physical abnormalities (MPAs) are considered subtle phenotypic imprints of developmental abnormalities of morphological features seen in the eyes, ears, mouth, head, hands, and feet that have no substantial cosmetic or clinical consequence.1 The well-documented higher rate of MPAs in schizophrenia supports the neurodevelopmental model.2-6 As MPAs reflect adverse events that occur during crucial developmental times, these characteristics may offer indirect hints of brain dysfunction and potentially reveal clues to the process of schizophrenia.3-9 Sex difference is a crucial part of the neurodevelopment hypothesis and may contribute to elucidating the etiology of schizophrenia.7 There is some evidence that MPAs are more prominent in male than in female schizophrenic patients.7,10,11 In contrast, Green et al.12 found a trend towards higher MPA scores in female than male schizophrenia patients. The issue of whether specific anomalies or body regions are more common in patients with schizophrenia has also attracted attention.13-16 MPAs are more typically found in the craniofacial region than in other sites in patients with schizophrenia, according to several studies,6-8,10,12,17 but not confirmed in a meta-analysis.2 During the 5th −13th weeks of gestation, the craniofacial region and the brain develop from the same ectodermal tissue, and the craniofacial findings may implicate critical stages of neurodevelopment in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia.9 Individual mouth and head malformations might be more relevant to neurodevelopmental problems than the cumulative prevalence of MPAs.17 Hennesy et al.13 described significant facial dysmorphology in schizophrenia among males, particularly females. Turetsky et al.14 pointed out that posterior nasal volume decrement abnormalities in male schizophrenic patients seem to be sex-specific. Compton et al.15 found some sex-specific quantitative facial measurement differences between schizophrenic cases and controls. Delice et al.16 found particular sex-related predilections in the differences in palate parameters between patients with schizophrenia and control subjects. The contrasting topography of MPA stigmatization presented with relatively more pronounced peripheral dysmorphia in male schizophrenics and craniofacial dysmorphia in female schizophrenics provokes speculation about sexual dimorphism.7

The mouth region is sensitive to MPAs in patients with schizophrenia, with the highest prevalence of palate and tongue anomalies being the most frequently reported structures.1,5,8,10,12 Previous studies have indicated the presence of a high-arched and narrow palate in schizophrenia.8,9,12 McGrath et al.5 were among the first researchers to observe a correlation between the skull base width and the palate width related to patients with schizophrenia. Two-blind, quantitative studies also showed that people with schizophrenia had a significantly broader palate than the matched control group.16,18 In a current study, grooved palate and parabolic dental arch shapes were observed to be morphological features of the palate in male patients with schizophrenia.19 The palate is part of a bony structure; the base of the temporal lobe sits, and primary palate formation involves a sequence of processes closely associated with craniofacial growth.20 From an embryological perspective, disturbances in the normal development of the palate are closely related to adjacent anatomical oral structures, such as the palatal rugae.21,22

Palatal rugae are asymmetrical, irregular mucosal ridges on either side of the median palatine raphe in the anterior portion of the hard palate. In the third month of intrauterine life, they arise with connective tissue covering the palatine process of the maxillary bone.23 Like fingerprints, each person has a unique arrangement, shape, and length of their palatal rugae.24 Insignificant sexual dimorphism in the rugae pattern was documented in certain studies,25,26 however, significant differences in the rugae pattern among male, female, and transgender populations were reported in another study.27 Due to individual variations and the complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors in the palatal rugae morphology, the diversity in rugae patterns and the potential for sex discrimination among different populations have varying results.23

Palatal rugae constitute an exciting field of MPAs for patients with schizophrenia because of their genetic origins and developmental processes, their emergence between the 12th and 14th weeks of prenatal life, their lifetime stability, their close relationship with the palate, and being a little-researched topic. Several previous studies evaluating MPAs reported a decreased number of palatal rugae5,28 or an increased number of palate rugae29 in patients with schizophrenia compared to healthy subjects. Tysiac-Mista et al.30 also conducted a qualitative analysis of the palatal rugae, which did not indicate a significant pattern, which could be characteristic of people with schizophrenia. A later study showed substantial differences in the palate shape and the rugae orientation between male schizophrenics and male controls.31 Rugal patterning may have the potential to be a sensitive sign of a genetically or environmentally influenced developmental disorder.32 Thus, we aimed to compare the palatal rugae pattern, according to their length, shape, and orientation, between patients with schizophrenia and nonpsychiatric controls in a blinded manner. We also evaluated palatal rugae patterns by sex.

MethodsSetting and sampleThe schizophrenia group consisted of 105 outpatients admitted to the University of Health Sciences, Bakirkoy Training and Research Hospital for Psychiatry, Neurology, and Neurosurgery during the period of September 2022 to January 2023, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria for diagnosis.33 During the univariate evaluation, the homogeneity of the categories was taken into account. The control group included 105 individuals who had been admitted to the general oral and dental health facility. The eligibility criteria for subjects in the study were adults over 18 years of age with natural dentition. Exclusion criteria for the study groups were a history of alcoholism or drug addiction, a history of somatic disorder with neurological components, a history of head injury, a history of epilepsy, identified craniofacial syndrome, diagnosed organic brain disease, a history of oral and maxillofacial surgery, a history of palatal pathology, previous history of palate fracture, to exhibit bony and soft tissue primary protuberances, active lesions, severe palatal burns, and having a fixed orthodontic appliance. To prevent possible confounding due to the ethnic and racial references to palatal rugae patterns, both the patient and control groups were of Turkish origin. All participants and caregivers supplied informed consent in writing.

ProceduresGood-quality dental stone casts of the maxillary arch, including the hard palate, obtained from alginate impressions were available for all subjects. Any defective dental stone study models were excluded. An examiner (ÖO), blinded to the group membership of the subjects, carried out the process of determining, classifying, and recording the number of the rugae. To eliminate the measurement error, the same observer reevaluated 20 randomly selected dental casts one month later to assess intraobserver reliability. All rugae outline on the casts were marked with a black marker under adequate lighting.

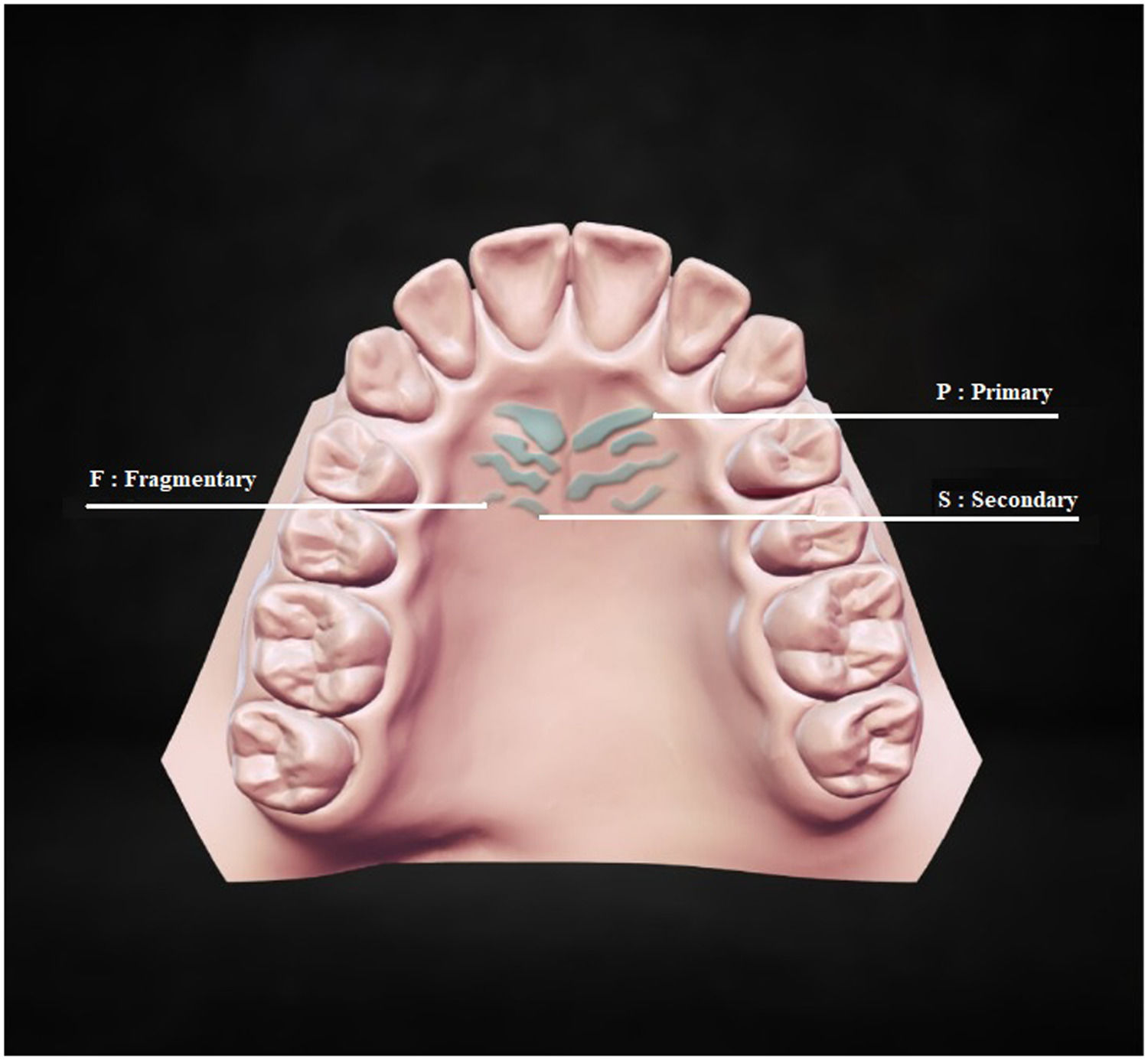

Rugae classification consisted of three parts. The first part classified palatal rugae into three types according to their length measured on both sides using a digital sliding caliper calibrated to 0.01 mm. 34 Based on their length, different palatal rugae types are depicted in Fig. 1. P: Primary rugae, more than 5 mm in length; S: Secondary rugae, 3 to 5 mm in length; F: Fragmentary rugae, 2 to 3 mm in length (Fig. 1). Palatal rugae of less than 2 mm in length were not considered. Primary rugae were further evaluated in shape and orientation, but secondary and fragmentary ones were not.

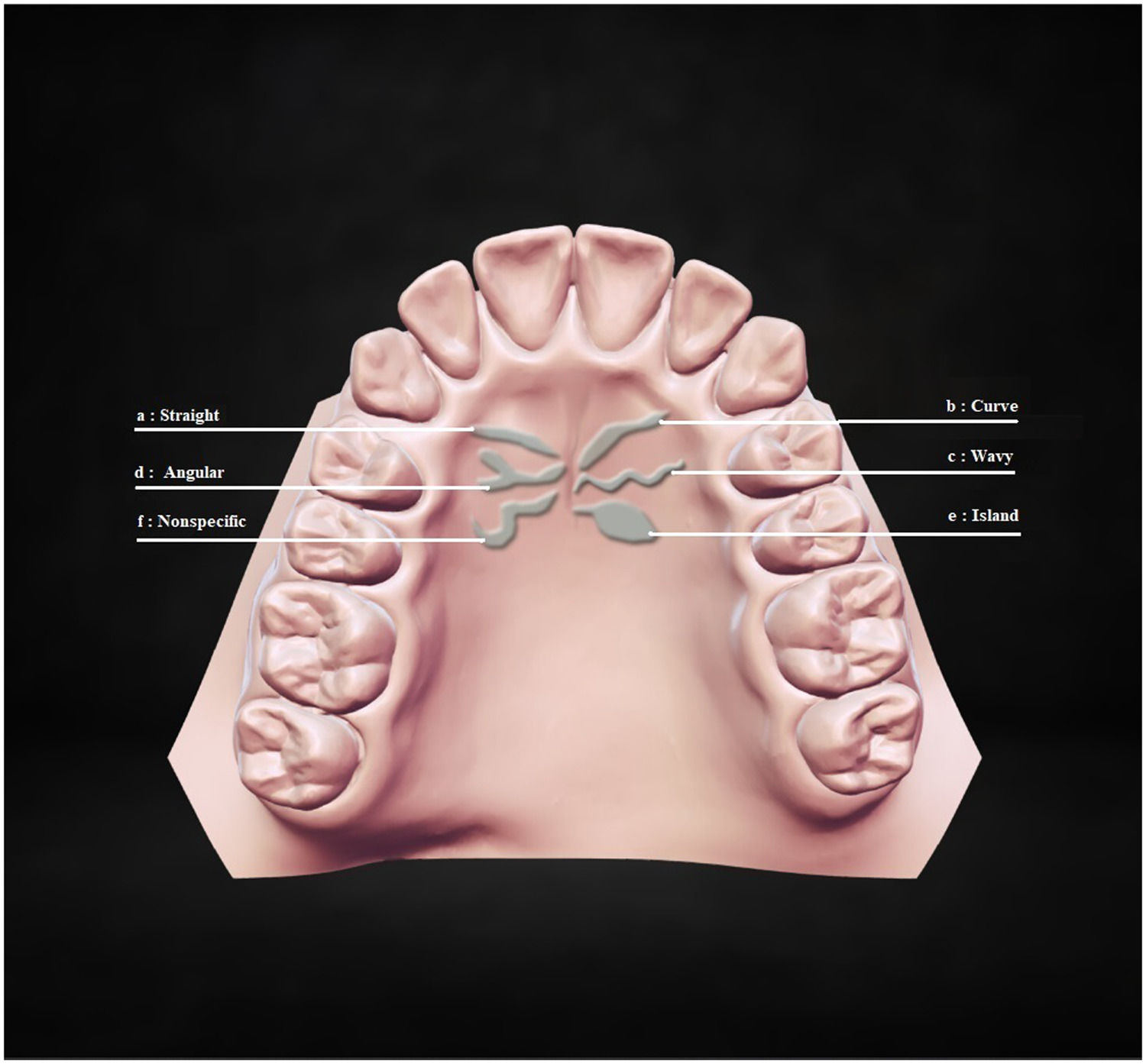

The second part classified primary rugae into six types according to their shape: straight, curved, wavy, angular, island, and nonspecific.35 Different primary rugae types by shapes are presented in Fig. 2. a: Straight, flat shape directly from their origin to termination; b: Curve, crescent shape with a slight bend; c: Wavy, serpentine shape with a slight curve at the beginning or end; d: Angular, joined shape at the start or end points of two rugae; e: Island, definite circular formation at the extreme; f: Nonspecific, any shape that did not fall into this category (Fig. 2).

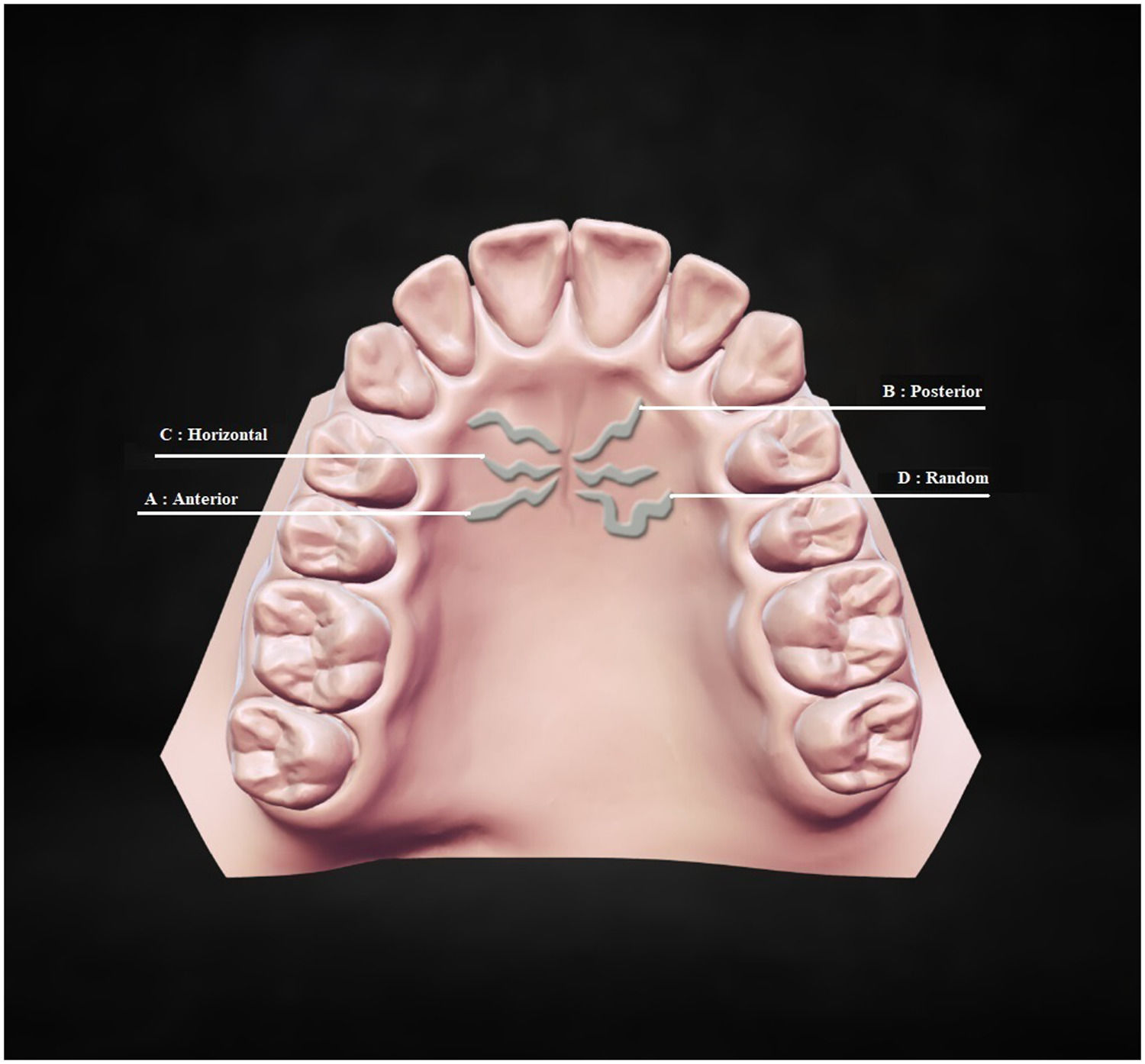

The third part categorized the primary rugae into four types according to their orientation: anterior, posterior, horizontal, and random.36 Based on their direction, various primary rugae types are shown in Fig. 3. A: Anterior; primary rugae is posterior-anterior oriented; B: Posterior; primary rugae is anterior-posterior oriented; C: Horizontal; primary rugae is perpendicular to median palatine raphe; D: Random; primary rugae is irregularly oriented (Fig. 3).

Data analysisUsing SPSS for Windows, data were analyzed (version 20.0, SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, US). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to determine whether the data had a normal distribution. Continuous data were compared using the Student's t-test for parametric distributions and the Mann-Whitney U test for nonparametric distributions. For qualitative data, the Pearson chi-square test was used. To determine the primary rugae pattern that best predicts patients with schizophrenia and controls, Stepwise Logistic Regression Analysis was applied with a confidence interval of 95% in multivariate analyses. To adjust the effect of sex, independent variables were included in the model through their interactions with sex. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Kappa statistic (K value) was used to quantify the intra-examiner agreement for the classification of primary rugae shape and direction, while the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to measure the agreement on palatal rugae length.

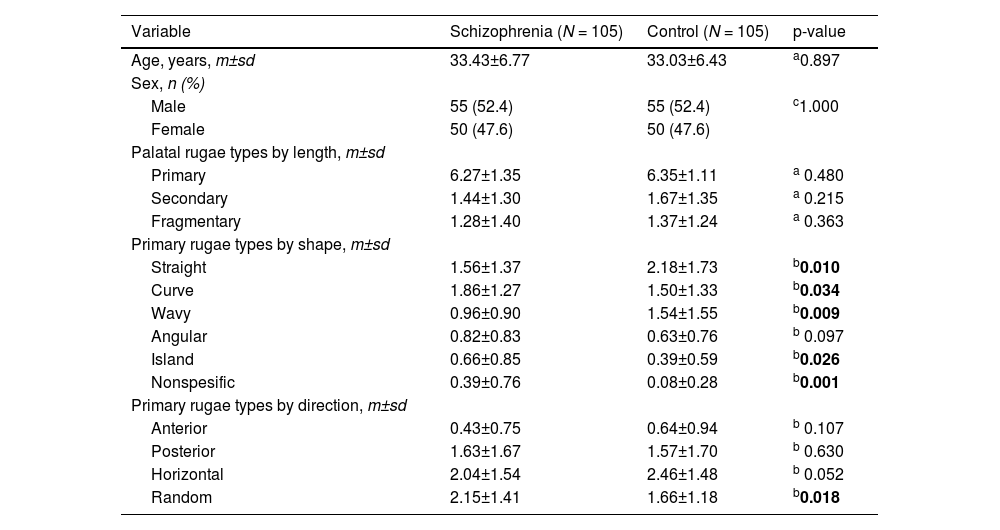

ResultsThe sample of this study consists of adults ranging in age from 18 to 52 years (33.54±6.38). A comparison of demographic characteristics and palatal rugae parameters of patients with schizophrenia and controls is presented in Table 1. There was no difference between the two groups in terms of age and sex distribution. As a result of the evaluations made for intraexaminer reliability, each K value and ICC were found to be greater than 0.70.

Comparison of age, sex, and palatal rugae parameters between schizophrenia and control group.

| Variable | Schizophrenia (N = 105) | Control (N = 105) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, m±sd | 33.43±6.77 | 33.03±6.43 | a0.897 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 55 (52.4) | 55 (52.4) | c1.000 |

| Female | 50 (47.6) | 50 (47.6) | |

| Palatal rugae types by length, m±sd | |||

| Primary | 6.27±1.35 | 6.35±1.11 | a 0.480 |

| Secondary | 1.44±1.30 | 1.67±1.35 | a 0.215 |

| Fragmentary | 1.28±1.40 | 1.37±1.24 | a 0.363 |

| Primary rugae types by shape, m±sd | |||

| Straight | 1.56±1.37 | 2.18±1.73 | b0.010 |

| Curve | 1.86±1.27 | 1.50±1.33 | b0.034 |

| Wavy | 0.96±0.90 | 1.54±1.55 | b0.009 |

| Angular | 0.82±0.83 | 0.63±0.76 | b 0.097 |

| Island | 0.66±0.85 | 0.39±0.59 | b0.026 |

| Nonspesific | 0.39±0.76 | 0.08±0.28 | b0.001 |

| Primary rugae types by direction, m±sd | |||

| Anterior | 0.43±0.75 | 0.64±0.94 | b 0.107 |

| Posterior | 1.63±1.67 | 1.57±1.70 | b 0.630 |

| Horizontal | 2.04±1.54 | 2.46±1.48 | b 0.052 |

| Random | 2.15±1.41 | 1.66±1.18 | b0.018 |

m:mean, sd:standard deviation, N:number of cases;%: percentage of the group;.

Bold items indicate statistically significant differences, p< 0.05.

The number of primary, secondary, and fragmentary palatal rugae did not differ substantially between patients with schizophrenia and controls. Regarding the lengths of the palatal rugae classification, the most common rugae were the primary ones (Table 1).

As shown in Table 1, statistically significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of the shape and direction of the primary rugae. The number of straight (p = 0.01) and wavy (p = 0.009) primary rugae were significantly higher in the control group than in the schizophrenia group, whereas, in the schizophrenia group, the number of the curved (p = 0.034), island (p = 0.026) and nonspecific (p = 0.001) primary rugae were significantly higher than those in the controls. Using the classification technique employed in this study, the results showed that the most prevalent primary rugae shape was straight in the controls, followed by curved and wavy. In patients with schizophrenia, curved was the most common primary rugae, followed by straight and wavy (Table 1).

The most prevalent primary rugae direction was horizontal in the controls, followed by random and posterior. In patients with schizophrenia, random was the most common primary rugae orientation, followed by horizontal and posterior. The least common rugae direction was anterior in both groups. On comparing the number of the primary rugae in schizophrenics and controls according to their direction, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups except for the number of randomly oriented primary rugae. Randomly oriented primary rugae was higher in the schizophrenia group than controls, the difference was statistically significant (p = 0.018) (Table 1).

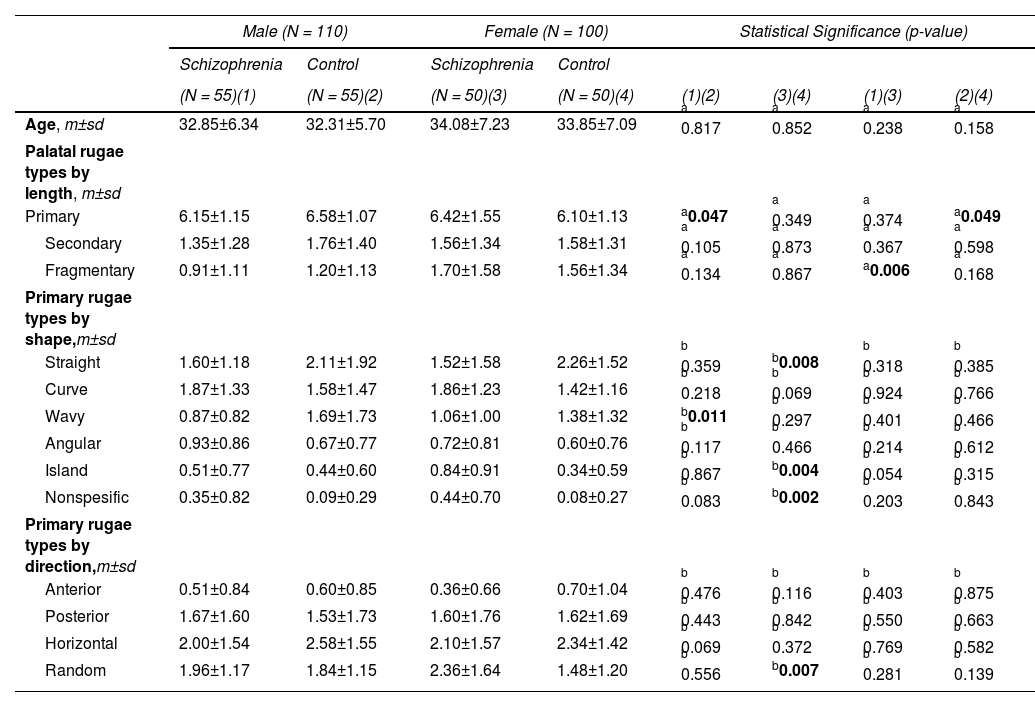

Statistical comparisons of palatal rugae parameters in the subgroups created based on sex are presented in Table 2. As shown, there were no sex differences in the shape and direction of the primary rugae between males and females in either the schizophrenia group or the control group. On the other hand, results showed that in the schizophrenia group, the two sexes exhibited distinct preferences for palatal rugae parameters compared to same-sex controls. Male patients with schizophrenia had fewer primary rugae than their male counterparts. The difference was statistically significant (p = 0.047). This was not the case for female patients with schizophrenia compared to female controls (Table 2).

Comparison of age and palatal rugae parameters between schizophrenia and control groups based on sex.

| Male (N = 110) | Female (N = 100) | Statistical Significance (p-value) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia | Control | Schizophrenia | Control | |||||

| (N = 55)(1) | (N = 55)(2) | (N = 50)(3) | (N = 50)(4) | (1)(2) | (3)(4) | (1)(3) | (2)(4) | |

| Age, m±sd | 32.85±6.34 | 32.31±5.70 | 34.08±7.23 | 33.85±7.09 | a 0.817 | a 0.852 | a 0.238 | a 0.158 |

| Palatal rugae types by length, m±sd | ||||||||

| Primary | 6.15±1.15 | 6.58±1.07 | 6.42±1.55 | 6.10±1.13 | a0.047 | a 0.349 | a 0.374 | a0.049 |

| Secondary | 1.35±1.28 | 1.76±1.40 | 1.56±1.34 | 1.58±1.31 | a 0.105 | a 0.873 | a 0.367 | a 0.598 |

| Fragmentary | 0.91±1.11 | 1.20±1.13 | 1.70±1.58 | 1.56±1.34 | a 0.134 | a 0.867 | a0.006 | a 0.168 |

| Primary rugae types by shape,m±sd | ||||||||

| Straight | 1.60±1.18 | 2.11±1.92 | 1.52±1.58 | 2.26±1.52 | b 0.359 | b0.008 | b 0.318 | b 0.385 |

| Curve | 1.87±1.33 | 1.58±1.47 | 1.86±1.23 | 1.42±1.16 | b 0.218 | b 0.069 | b 0.924 | b 0.766 |

| Wavy | 0.87±0.82 | 1.69±1.73 | 1.06±1.00 | 1.38±1.32 | b0.011 | b 0.297 | b 0.401 | b 0.466 |

| Angular | 0.93±0.86 | 0.67±0.77 | 0.72±0.81 | 0.60±0.76 | b 0.117 | b 0.466 | b 0.214 | b 0.612 |

| Island | 0.51±0.77 | 0.44±0.60 | 0.84±0.91 | 0.34±0.59 | b 0.867 | b0.004 | b 0.054 | b 0.315 |

| Nonspesific | 0.35±0.82 | 0.09±0.29 | 0.44±0.70 | 0.08±0.27 | b 0.083 | b0.002 | b 0.203 | b 0.843 |

| Primary rugae types by direction,m±sd | ||||||||

| Anterior | 0.51±0.84 | 0.60±0.85 | 0.36±0.66 | 0.70±1.04 | b 0.476 | b 0.116 | b 0.403 | b 0.875 |

| Posterior | 1.67±1.60 | 1.53±1.73 | 1.60±1.76 | 1.62±1.69 | b 0.443 | b 0.842 | b 0.550 | b 0.663 |

| Horizontal | 2.00±1.54 | 2.58±1.55 | 2.10±1.57 | 2.34±1.42 | b 0.069 | b 0.372 | b 0.769 | b 0.582 |

| Random | 1.96±1.17 | 1.84±1.15 | 2.36±1.64 | 1.48±1.20 | b 0.556 | b0.007 | b 0.281 | b 0.139 |

m:mean, sd:standard deviation, N: number of cases;%:percentage of the group.

Bold items indicate statistically significant differences, p< 0.05.

In terms of shape, the numbers of the island (p = 0.004) and nonspecific (p = 0.002) primary rugae were significantly higher in female patients with schizophrenia than in the control females, while the number of straight primary rugae (p = 0.008) was lower in female patients with schizophrenia. The same was not true of male schizophrenics compared to male controls. In male patients with schizophrenia, the number of wavy primary rugae was less than in male controls. The difference was statistically significant (p = 0.011). The situation differed between female patients with schizophrenia and female controls (Table 2).

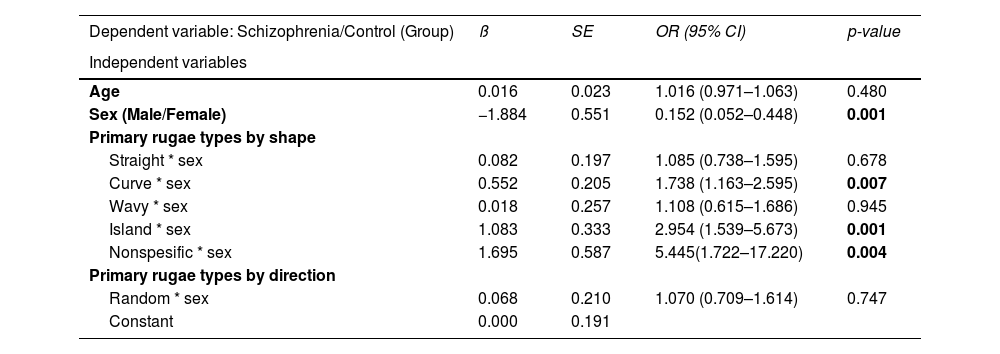

A logistic regression model was constructed using schizophrenia versus control status as the dependent variable. As shown, sex was found to be significant (OR:0.15; 95% CI: 0.05–0.44, p = 0.001). Based on the variables that were significant in the first stage, a multivariate analysis was performed by controlling the sex effect, and as a result, the independent variables that had the power to predict schizophrenia were indicated in Table 3. To adjust the effect of sex, independent variables were included in the model through their interactions with sex. As a result of analysis, curved (OR: 1.76; 95% CI: 1.17–2.64, p = 0.006), island (OR: 2.97; 95% CI: 1.54–5.70, p = 0.001), and nonspecific primary rugae (OR:5.44; 95% CI: 1.72–17.22, p = 0.004) represented the significant predictive factors for patients with schizophrenia (Table 3).

Results of logistic regression analysis. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Bold items indicate statistically significant differences, p< 0.05.

This study focused specifically on palatal rugae on the palate, which is a typical region for schizophrenia-related MPAs, and is one of the few to evaluate the topic in this special population. The main finding obtained from this study was that the number of palatal rugae types by length did not differ between schizophrenics and controls, but there were significant differences in primary rugae numbers in terms of shape and direction. Besides, the current study endeavoring to distinguish schizophrenic patients from controls revealed that three variables related to the shape of the primary rugae significantly predicted patients with schizophrenia. These variables consisted of the curved, island, and nonspecific shape. The results also demonstrated that patients with schizophrenia exhibit sex-related predilections in rugae shapes compared to same-sex controls. To our knowledge, two studies have conducted quantitative and qualitative evaluations of palatal rugae on dental casts from patients with schizophrenia.30,31 In the first study, the authors revealed that palatal rugae characteristics did not differ significantly between the patients and controls, except for an increased number of posteriorly directed and curved shapes in patients with schizophrenia.30 In the second study, the authors reported a more random distribution of palatal rugae directions in patients with schizophrenia than in the controls which is consistent with our study findings.31

In recent years, there has been an increase in anatomical and physiological research on individual morphological features as specific markers of dysmorphogenesis in schizophrenia. Specific MPAs could be a marker of the severity of disease manifestation which could be predicting an early onset, and perhaps a more severe course of the illness and would aid in personalizing treatments.3 On the basis of the correlation between the face and brain, both qualitative and quantitative oral findings may implicate crucial phases of neurodevelopment in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia.3-5,8,9

Palatal rugae is also an oral anatomic feature that expresses considerable inter-individual variability. The rugae shape is more important than the rugae number in population definition because rugae shape is a distinctive variable that remains constant throughout life.34 It is believed that the rugae shape is mostly genetically controlled because the genes determine the orientation of collagen fibers within the connective tissue of the rugae, thereby governing the rugae pattern of the diverse racial groups.23

The formation of the palate and related structures involves a series of local cellular changes during the craniofacial growth period.20 For craniofacial growth and development, complex interactions between Hedhegog signaling and Fibroblast growth factor pathways are required.37 Overexpression of Hedhegog signaling causes hypertelorism, while underexpression causes facial clefting and abnormalities of other frontonasal and maxillary process-derived facial structures.38 Hedhegog signaling is also regarded as a key factor in the development of the palate and palatal rugae.41 Disruption of Hedhegog signaling and Fibroblast growth factor signaling, as well as altered expressions, may result in abnormal rugae patterns characterized by spotted, irregular, or disorganized palatal rugae.39,40 There is also an evidence suggesting that altered Hedhegog signaling may be an important neurodevelopmental factor in the pathobiology of mental illness.41 Thus, the significant differences in primary rugae shape in this schizophrenia sample might suggest commonly shared specific developmental signaling pathway dysfunction during the process of these structures.

Various anomalies in mutant mice have been demonstrated compared to wild-type mice, which mainly had straight and wavy rugae.42 In fact, the most prevalent type of palatal rugae in mammals other than humans is straight. Evolutionary variations in the size of the human jaws and palate may have resulted in the formation of the palatal rugae with shapes other than straight ones.40 According to these findings, it is possible that the only true shapes of primary rugae are straight and wavy, while branching and other polymorphic varieties may be phenotypic variants or anomalies. In this context, the reduced number of straight and wavy primary rugae in patients with schizophrenia is a noteworthy finding of our study. The difficulty in differentiating the shape (nonspecific) and orientation (random) of the primary rugae in schizophrenics in this study may be justified by intrauterine and perinatal developmental alterations. Additionally, the higher presence of nonspecific primary rugae may indicate the necessity of describing new rugae patterns in a larger sample of patients with schizophrenia. In this context, the results of this study may serve as preliminary indicators of the possible significance of the primary rugae pattern as a specific marker of dysmorphogenesis in patients with schizophrenia.

We also compared the palatal rugae parameters between the two groups in terms of sex, given that sex disparity is a crucial aspect of the neurodevelopment hypothesis in schizophrenia.7 Similar rugae patterns were observed in control males and females in this study, consistent with the findings of several studies.25,26,43 This analogous pattern seen was also observed in the schizophrenia group. Regarding sexual dimorphism and population characterization of the palatal rugae patterns, there are inconsistent findings.23 To date, there has been little agreement on whether palatal rugae patterns can be used to predict sex, and the majority of studies have recommended using palatal rugae in conjunction with other methods for sex identification.25 However, male and female patients with schizophrenia had distinct susceptibilities to palatal rugae parameters in comparison to controls of the same sex. The two intersex comparisons revealed that island and nonspecific primary rugae were significantly higher in female schizophrenics than in their female counterparts. In contrast, the same was not true for males. Among the significant differences between the schizophrenia and control groups, the number of randomly oriented primary rugae was influenced by the female sex variable, but this was not the case when comparing male controls to male schizophrenics. The probability of having MPA is significantly higher in both sexes than in normal controls, tending to be more pronounced in males.7,10,11 The sex-related preference trend for increased MPAs in schizophrenia in terms of affected topographic regions is considered with relatively more pronounced peripheral dysmorphia in male schizophrenics and more prominent craniofacial dysmorphia in female schizophrenics.7 In this study, the differences in primary rugae shape and direction between the schizophrenia group and the control group appeared to be more pronounced in schizophrenic females than in schizophrenic males, lending credence to this idea. Our findings also seem to be in line with a previous study showing that two sexes show different susceptibilities in palate shape and size in schizophrenics compared to same-sex controls,16 and support the idea that there may be sex-specific variations in the epidemiology of schizophrenia.13-16

This study has the following limitations: A single investigator's manual drawing and subjective evaluation of palatal rugae can be called into doubt the reliability of the qualitative method. However, descriptive statistics regarding intra-rater reliability did not indicate the presence of substantial errors in terms of outliers or excessive variation between the two measures. The classifications we used for the shape and orientation of the palatal rugae were kept deliberately uncomplicated because we were only interested in identifying the major differences in rugae patterning between patients and controls. Future research may explore a more detailed palatal rugae pattern in patients with schizophrenia using three-dimensional imaging technology.

ConclusionIn conclusion, the identification of subtle variations, which appear to be sex-specific, in the primary rugae shape and direction, particularly curve, island, and nonspecific shapes as significant predictive factors, are consistent with the hypothesis of abnormal neurodevelopment in schizophrenia. However, it is difficult to argue that patients with schizophrenia display a particular abnormality in the development of palatal rugae, so this study might contribute to the assumption that there are possible variations of the palatal rugae patterns which could present specific markers of embryological dysmorphogenesis underlying schizophrenia. Considering that it is a relatively new theme, there is a need for further research in this field.

Ethical statementThe University of Health Sciences, Bakirkoy Dr. Sadi Konuk Training and Research Hospital Clinical Research Ethics Committee granted approval for this study (date: 2022-17-06, number: 2022-278). This study was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards set forth in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent revisions.

FundingThere was no funding for this study.

Data availabilityThe data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contributionsOO, CO, EK, ZDG, HB, ÖEÇ were involved in the conceptualization of the study, design of the study, interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation. OO, ZDG, and HB were involved in data collection, data analysis, and interpretation of results. OO, ZDG, and ÖEÇ wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors contributed to revisions. All authors have approved the final manuscript.

None.