Archaeological, epigraphic, and ethnohistoric studies indicate that world renewal rituals were an important feature of prehispanic Maya society and continue to play a seminal role in indigenous communities throughout the Maya area today. Our discussion examines two examples of the multitude of such rituals that were performed to recreate the world by replicating the actions undertaken by the primordial deities at the beginning of the present creation. The first involves ceremonies performed by the Yucatec Maya during the Postclassic period (13th through 15th centuries) to ritually terminate the old year and begin anew by establishing a “tree” to mark the trees set up in the four quadrants at the creation of the present world, as documented in the prehispanic Maya codices and the colonial period Books of Chilam Balam, written by indigenous scribes in the alphabetic script introduced by the Spanish friars in the 16th century. The second involves Ch’orti’ speakers living in southern Guatemala today, who perform similar rituals that involve a series of ceremonies undertaken over the course of the rainy season to ensure agricultural fertility. Both ritual complexes involve foundation events, acts of sacrifice, petitions to the rain and earth deities, and an emphasis on sacred watery places.

Los estudios arqueológicos epigráficos y etnohistóricos indican que los rituales de renovación del mundo constituyeron un rasgo importante de la sociedad maya prehispánica y continúan desempeñando un papel fundamental en las comunidades mayas actuales. Aquí examinaremos dos ejemplos de tales rituales realizados para recrear el mundo replicando las acciones de las deidades primordiales al inicio de la creación actual. El primero involucra las ceremonias realizadas por los mayas yucatecos del periodo Posclásico, para terminar el año viejo e iniciar el nuevo estableciendo un “árbol” para evocar aquellos árboles erigidos en los cuatro cuadrantes al inicio del mundo presente, tal y como está documentado en los códices mayas prehispánicos y en los Libros del Chilam Balam del período colonial, escritos por indígenas con la escritura alfabética introducida por los frailes españoles en el siglo xvi. El segundo involucra a los hablantes de ch’orti del sur de Guatemala que ejecutan en la actualidad rituales similares, basados en una serie de ceremonias realizadas durante la temporada de lluvias para asegurar la fertilidad agrícola. Ambos complejos rituales incluyen eventos de fundación, sacrificio, peticiones a las deidades de la lluvia y un énfasis en lugares sagrados acuosos.

Andrea Stone’s work has served as an inspiration to both of us throughout our careers. We dedicate this paper to her memory as an esteemed colleague and valued friend.

Previous researchers have commented on connections between renewal ceremonies practiced in various contemporary Maya communities (see, e.g., Bricker, 1989, for Zinacantán, Chiapas; Gabriel, 2009, for Yucatán; Christenson, 2001, for Santiago Atitlán, Guatemala; and Thompson, 1999, for Tekanto, Yucatán) with those of the prehispanic period, specifically as depicted in the Dresden Codex “yearbearer” pages (i.e., those depicting the end of one year and the start of the next). Our decision to compare the prehispanic yearbearer ceremonies with agricultural renewal rituals practiced by the Ch’orti’ living today in southern Guatemala, chosen from among the dozens of ethnographic ceremonies that could have been selected, stems from the close similarities we have noted in their performances and the fact that they have not been previously compared. Although they are separated by great distances in time and space, our analysis suggests the possibility that renewal ceremonies similar to those depicted for the yearbearer days in the Maya codices were part of a widespread tradition that encompassed much, if not all, of the Maya region inhabited during the Terminal Classic and Postclassic periods.

Dresden Yearbearer RitualsEthnohistoric sources provide a wealth of detail regarding the ritual transition from one year (haab’) to the next among the Yucatec cultures on the eve of Spanish contact. This ceremonial transfer of power, involving a shift in the ruling deities, took place during the five days at the end of the year (the nameless days, or Wayeb’); and a second series of rituals was associated with the first day or days of the new year, occurring in the month of Pop (Tozzer, 1941: 136-153).

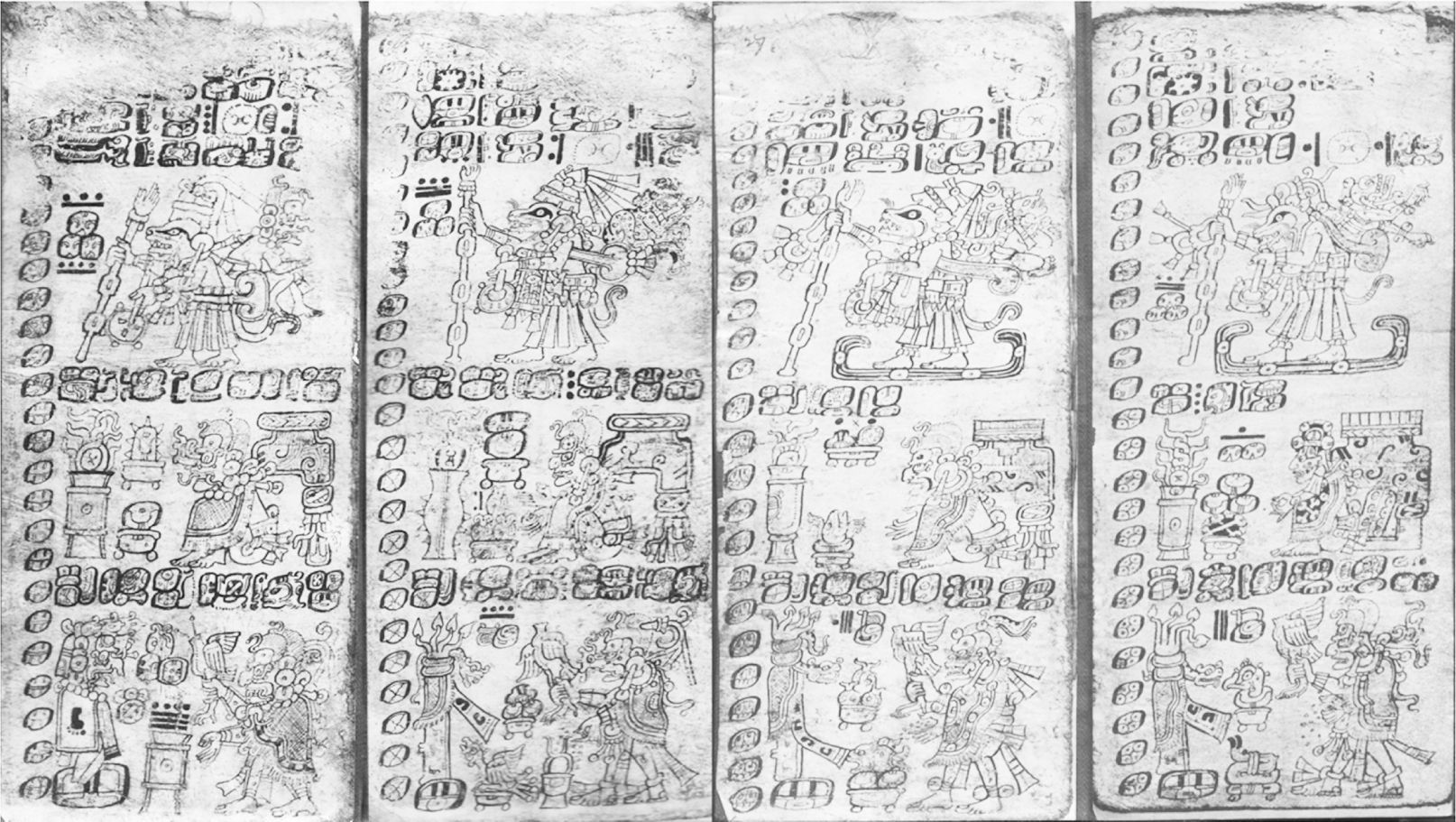

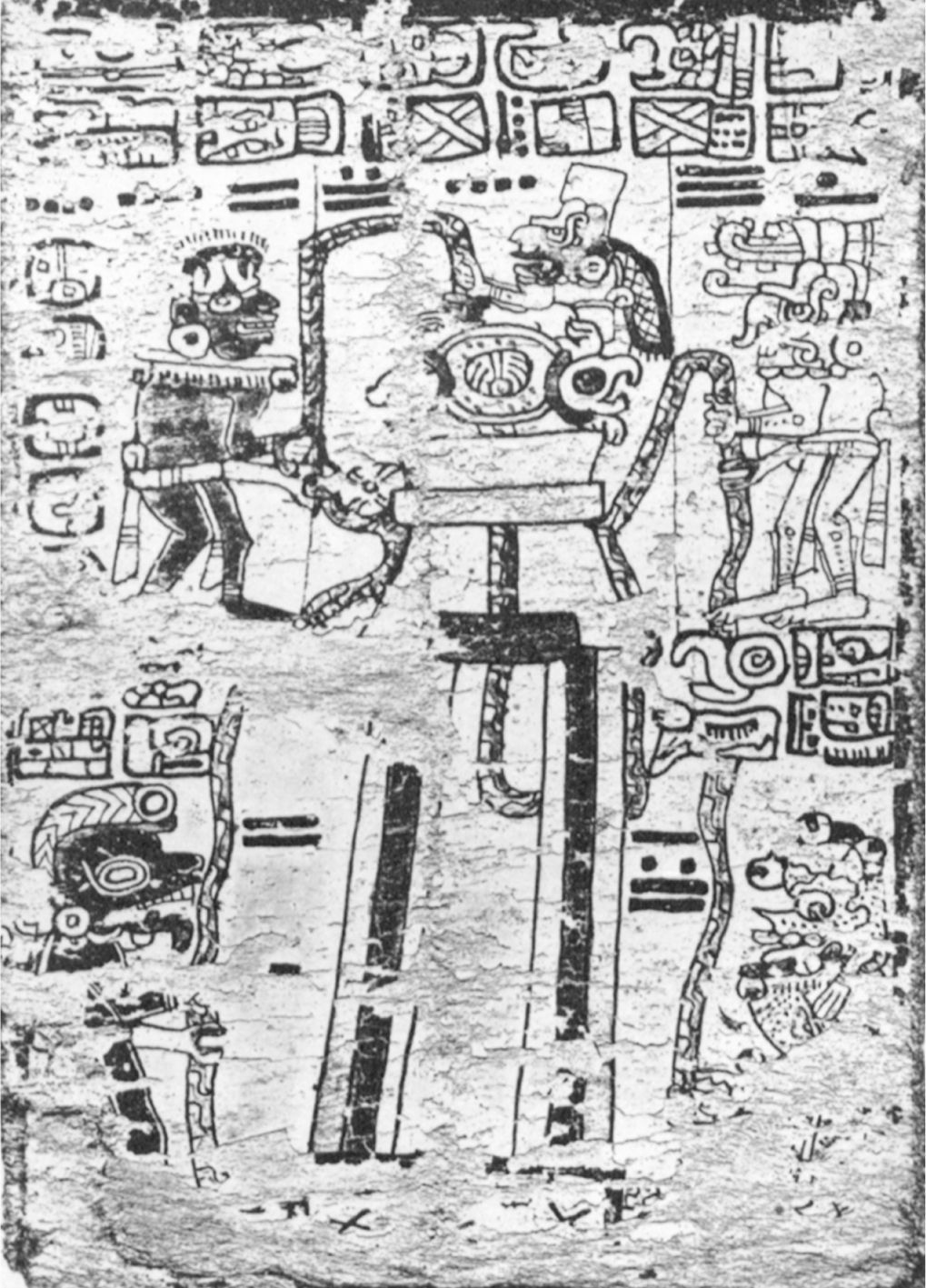

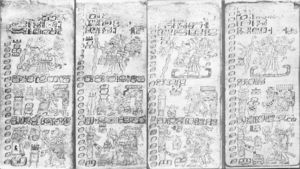

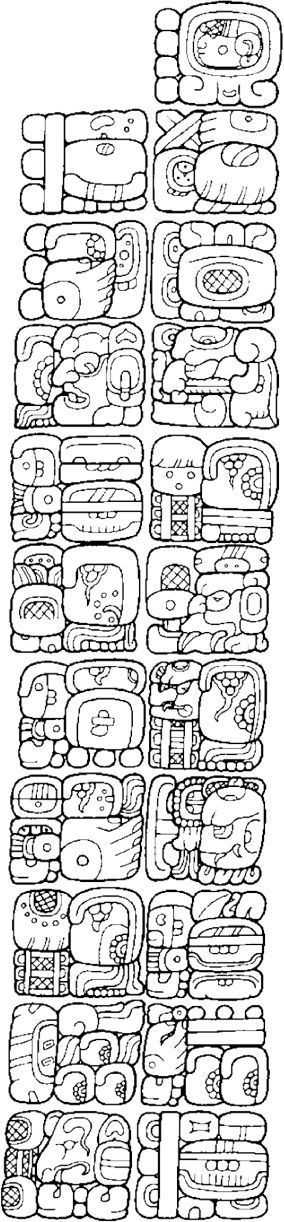

Pages 25-28 of the Dresden Codex (figure 1) have long been identified as being associated with the Wayeb’ ceremonies (Thomas, 1882; Thompson, 1972). There are significant points of comparison between ethnohistoric descriptions (particularly those of Bishop Diego de Landa) and the activities and events depicted on the Dresden pages. As Landa’s discussion makes clear, four of the days in the Maya tzolk’in calendar, consisting of 20 named days paired with 13 numbers, can begin the year. In the system in use at the time of the Conquest, these days were K’an, Muluk, Ix, and Kawak (Tozzer, 1941: 136-138).

Yearbearer ceremonies on pages 25-28 of the Dresden Codex. After Förstemann (1880)

A different yearbearer system has been documented for earlier time periods, however, in which the transition from the old year to the new year involved the days Ik’, Manik’, Eb’, and Kab’an, or alternately, Ak’b’al (the day after Ik’), Lamat (the day after Manik’), B’en (the day after Eb’), and Etz’nab’ (the day after Kab’an) (Edmonson, 1986). This is the system that appears in the Dresden Codex (Bricker and Vail, 1997). It is recorded not only in the yearbearer almanac on pages 25-28, but in other contexts as well, such as the almanac (also with a yearbearer function) on pages 31b-35b (see figure 3).

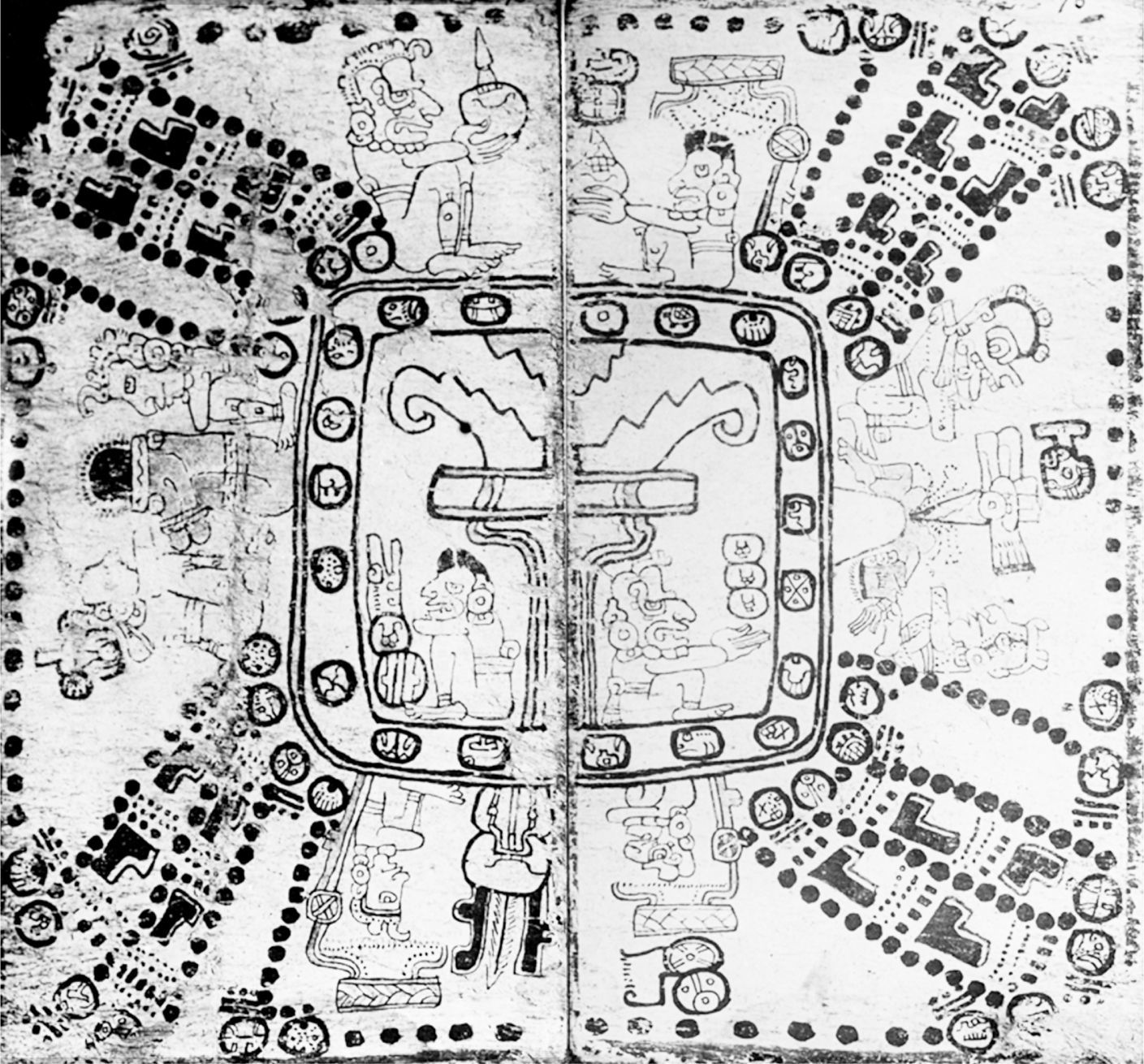

The calendar round almanac on pages 75-76 of the Madrid Codex. After Gates (1911)

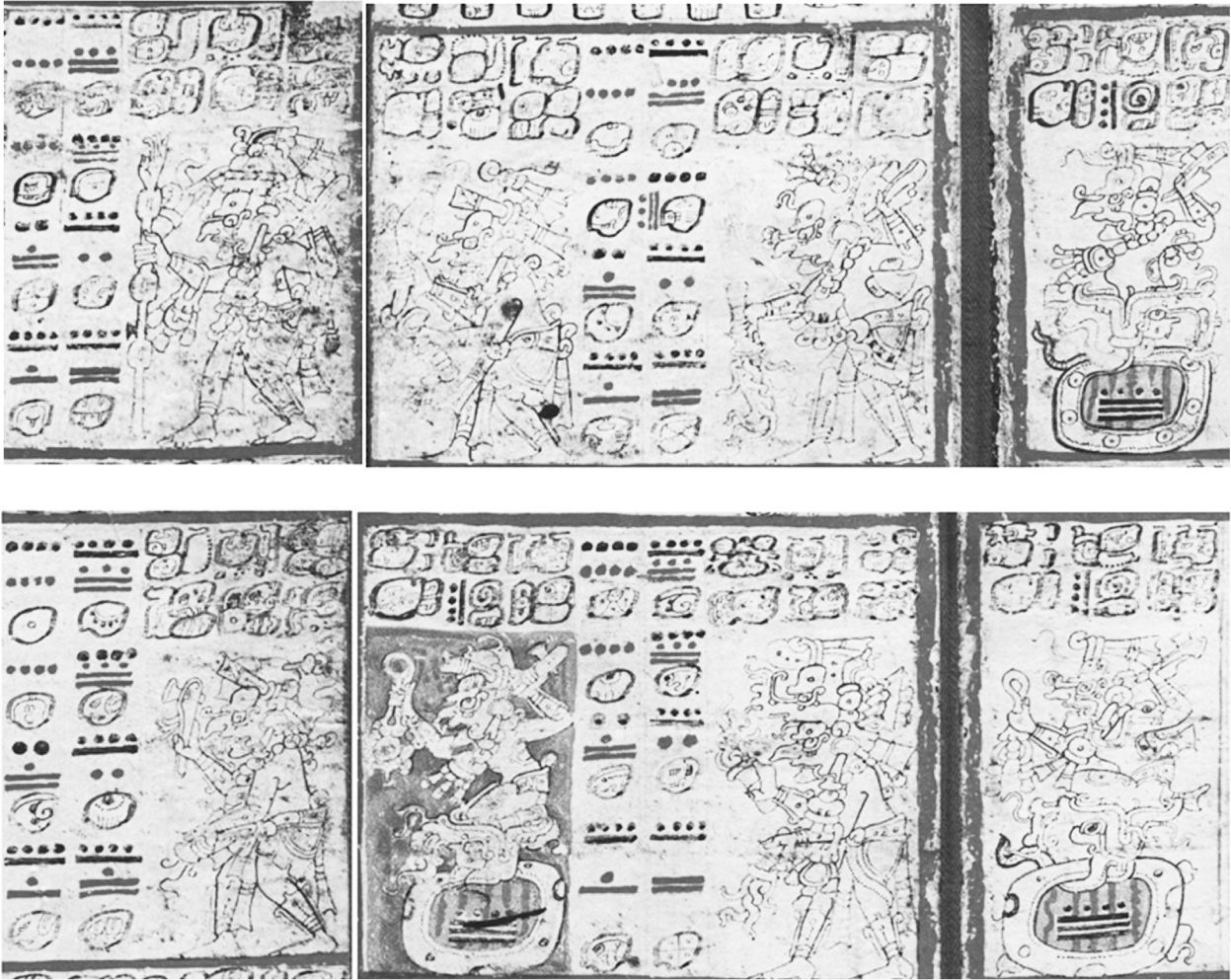

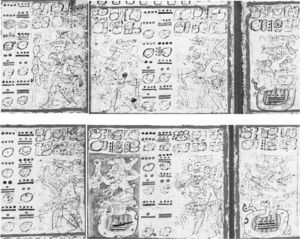

The birth of the rains, personified by Chaak, on Dresden Codex 31b-35b. After Förstemann (1880)

It takes 52 years to cycle through each of the four yearbearer days paired with the 13 numbers in the tzolk’in. In other words, the cycle at the time of Landa’s writing would have begun with a year 1 K’an, moved next (after 365 days) to 2 Muluk, from there, after another 365 days, to 3 Ix, then to 4 Kawak, 5 K’an, 6 Muluk … and finished with 13 Kawak. Returning to 1 K’an would have completed the 52-year cycle (figure 2).

The Dresden yearbearer pages reference two different dates on each page: Eb’ and B’en on D. 25, Kab’an and Etz’nab’ on D. 26, Ik’ and Ak’b’al on D. 27, and Manik’ and Lamat on D. 28. There has been a considerable amount of discussion concerning the position of these dates in the haab’ calendar —i.e., do they refer to the first and second days of Wayeb’ (H. Bricker and V. Bricker, 2011), or to the last day of Wayeb’ and the first day of Pop (Taube, 1988; Vail, 2004)? Our position is that the latter makes the most sense from a comparison of Landa’s description of the Wayeb’ events with the information detailed in the codex. We follow Vail and Hernández (2013), however, in suggesting that the lower register on each page serves a dual role —it marks the start of the rituals in a particular year, thereby corresponding to the first day of Wayeb’, after which one moves to the top of the next page (to the last day of Wayeb’), and then to the rituals associated with the beginning of Pop, illustrated in the bottom two registers of the page.

To take a concrete example, D. 25c shows the ritual that ends the sequence that was initiated on D. 28c and D. 25a and b.1 The ceremony involves the transfer of the deity patron of the year from the god of sustenance K’awil (on D. 28c and 25a-b) to the sun god K’inich Ahaw, who is installed as the patron of the new year on D. 25c. 360 days later, at the start of Wayeb’, this register (D. 25c) becomes relevant again, corresponding to Landa’s description of the ceremony at the edge of town in which offerings are made at an altar, and a hen is sacrificed. Landa’s “statue” (K’inich Ahaw) is then carried in a procession during which a number of dances are performed, as is illustrated on D. 26a. The key elements in this composition include the jaguar (an aspect of the sun god), who is being carried by an opossum figure dressed as a ritual performer (see Taube, 1989 and Vail, 2012 for a detailed discussion of this figure). This takes place on the last day of Wayeb’, after which the sun god is given offerings in the house of the principal, which include pom incense, seven hearts, and chak wah, a type of ritual “bread”. On the same day that the sun god’s rulership is ritually terminated, the patron of the next year (Itzamna) is installed as the new deity patron.

Important elements in the transfer include a shift in directional affiliations from east, associated with B’en years and the sun god, to north, associated with Etz’nab’ years and Itzamna, and the “deactivation” of the deity representative of the previous year which is suggested by the placing of his cape so that it covers the front of his body and by the shift in auguries to agree with those associated with the deaty in the lowe register, rather than the deity picture. The deities who serve as the patrons (or more appropriately “burdens”) of the year for all 52 years in the sequence include the sun god K’inich Ahaw and the jaguar for east years; the creator Itzamna and the maize god for north years; the death god for west years; and the god of lightning and sustenance K’awil for south years.

Not included in Landa’s discussion is the setting up of a “tree” to mark the beginning of the new year. In the Colonial period Books of Chilam Balam, trees were set up following a great food that destroyed the previous creation (Taube, 1988). The depictions of these trees in the Dresden Codex show them as personified stone columns (perhaps stalagmites),2 dressed in a loincloth and cape. At their top is vegetation and a snake, suggesting that they represent the akantun (ah, ‘he who’, kaan, ‘serpent’, tun, ‘stone’) discussed by Landa, where bloodletting rituals were performed during the yearbearer ceremonies (MacLeod, 1989; Tozzer, 1941: 141, 144).

On D. 25c, the rain deity Chaak personifies the tree (i.e., his head appears in place of the serpent). Both Chaak and serpents are symbolic of rain and the power of lightning to germinate seeds, suggesting the likelihood that the ceremonies being performed in the bottom register were agricultural and/or rainmaking rituals. This idea is reinforced by the burning of incense (an action that is performed in ceremonies today to call the rains) and the presence of possible stalagmites. If the stone objects do represent stalagmites, they were likely meant to symbolize a cave location; as Andrea Stone (1989, 2005) notes, yearbearer and other period-ending rituals were often performed in cave contexts. The presence of glyphs symbolizing cenotes in the upper registers on pages 27 and 28 is likewise suggestive of the performance of yearbearer ceremonies at watery, underworld locales.

That the Dresden yearbearer almanac was concerned with rituals to ensure adequate rainfall and thereby an abundant crop is also suggested by the hieroglyphic captions to the lower register, which give prognostications for each year. These vary from “woe to the maize and drought” on D. 25c to “an abundance of food and drink” on D. 28c. The yearbearer almanac in the Madrid Codex (M. 34-37) includes similar prognostications, which are displayed iconographically in addition to being included in the hieroglyphic captions. For example, the death god is shown in the lower left of M. 34 with the head of the rain god in his hand, likely signifying the death of the maize crop due to too little rain.

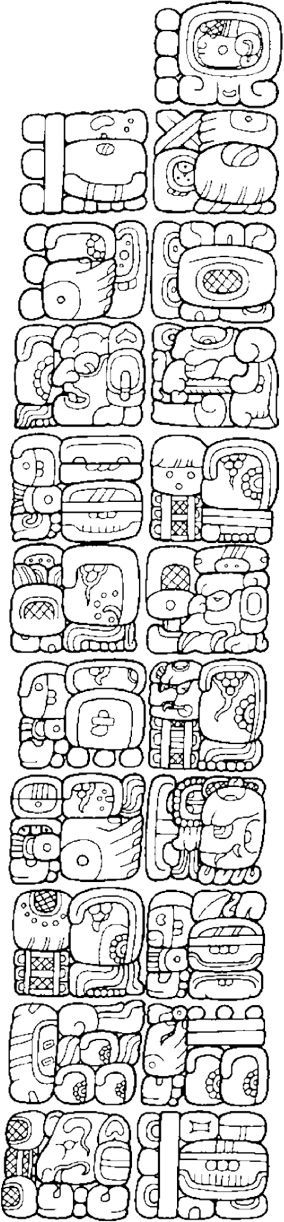

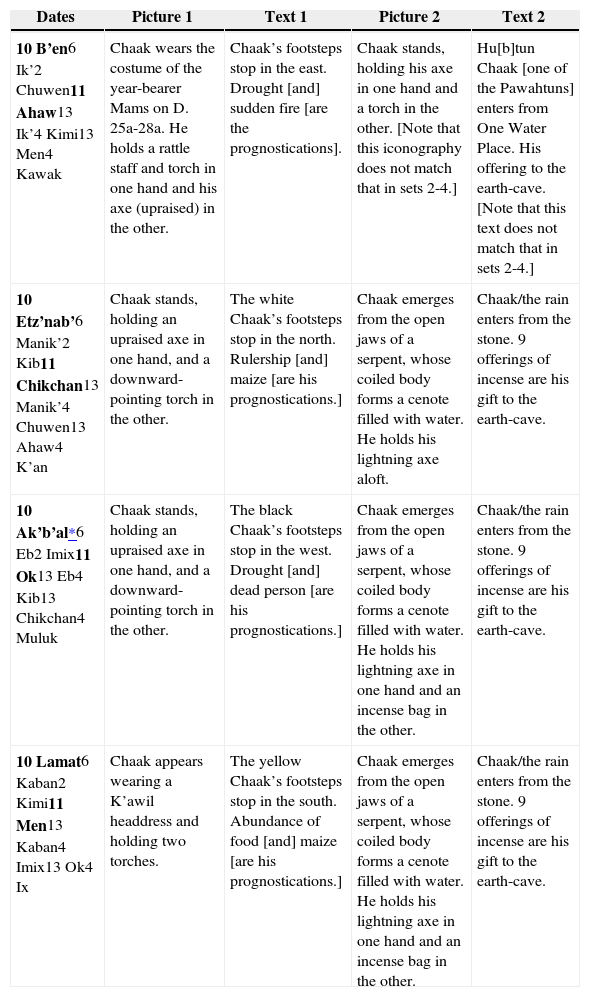

The almanac on D. 31b-35b (figure 3) also emphasizes yearbearer rituals, although in this case the protagonist in each of the frames is Chaak. The almanac includes four sets of dates, which include both yearbearer and “Burner” (fire) rituals. Each set of dates is associated with two separate pictures, organized as follows.

| Dates | Picture 1 | Text 1 | Picture 2 | Text 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 B’en6 Ik’2 Chuwen11 Ahaw13 Ik’4 Kimi13 Men4 Kawak | Chaak wears the costume of the year-bearer Mams on D. 25a-28a. He holds a rattle staff and torch in one hand and his axe (upraised) in the other. | Chaak’s footsteps stop in the east. Drought [and] sudden fire [are the prognostications]. | Chaak stands, holding his axe in one hand and a torch in the other. [Note that this iconography does not match that in sets 2-4.] | Hu[b]tun Chaak [one of the Pawahtuns] enters from One Water Place. His offering to the earth-cave. [Note that this text does not match that in sets 2-4.] |

| 10 Etz’nab’6 Manik’2 Kib11 Chikchan13 Manik’4 Chuwen13 Ahaw4 K’an | Chaak stands, holding an upraised axe in one hand, and a downward-pointing torch in the other. | The white Chaak’s footsteps stop in the north. Rulership [and] maize [are his prognostications.] | Chaak emerges from the open jaws of a serpent, whose coiled body forms a cenote filled with water. He holds his lightning axe aloft. | Chaak/the rain enters from the stone. 9 offerings of incense are his gift to the earth-cave. |

| 10 Ak’b’al*6 Eb2 Imix11 Ok13 Eb4 Kib13 Chikchan4 Muluk | Chaak stands, holding an upraised axe in one hand, and a downward-pointing torch in the other. | The black Chaak’s footsteps stop in the west. Drought [and] dead person [are his prognostications.] | Chaak emerges from the open jaws of a serpent, whose coiled body forms a cenote filled with water. He holds his lightning axe in one hand and an incense bag in the other. | Chaak/the rain enters from the stone. 9 offerings of incense are his gift to the earth-cave. |

| 10 Lamat6 Kaban2 Kimi11 Men13 Kaban4 Imix13 Ok4 Ix | Chaak appears wearing a K’awil headdress and holding two torches. | The yellow Chaak’s footsteps stop in the south. Abundance of food [and] maize [are his prognostications.] | Chaak emerges from the open jaws of a serpent, whose coiled body forms a cenote filled with water. He holds his lightning axe in one hand and an incense bag in the other. | Chaak/the rain enters from the stone. 9 offerings of incense are his gift to the earth-cave. |

Each set of dates is separated from the next by a period of 13 years, yielding a Calendar Round cycle highlighting the yearbearer dates 10 B’en (1 Pop), 10 Etz’nab’ (1 Pop), 10 Ak’b’al (1 Pop), and 10 Lamat (1 Pop). B’en years are associated with the east; Etz’nab’ years with the north; Ak’b’al years with the west; and Lamat years with the south, as is likewise the case on Dresden 25-28. Chaak is the protagonist of all eight pictures, the first of which shows him dressed as a yearbearer Mam. The other pictures in the first set also portray Chaak in the guise of a yearbearer, holding one or more lighted torches; note, however, that he wears a K’awil headdress in the last picture in this set, associated with the south. This is significant because K’awil is the burden of south years in the yearbearer almanac on D. 25-28.

The second set of pictures on D. 31b-35b depicts, in all but the first example, Chaak emerging from the open jaws of a serpent, whose body forms the walls of a cenote. The hieroglyphic captions refer to Chaak (or the rain) entering (i.e., emerging) from the stone. This is associated with nine offerings of incense to the earth-cave, or primordial place of creation. The D. 31b-35b almanac has a number of specific links to Ch’orti’ agricultural renewal ceremonies, as discussed below.

The Madrid Codex also details the ceremonies associated with the beginning of Pop. Among the other rituals that Landa discusses are those that involve drilling new fire and ritual cleansing (Tozzer, 1941: 151-152): To celebrate it [the new year] with more solemnity, they renewed on this day all the objects which they made use of, such as plates, vessels, stools, mats and old clothes and the stuffs with which they wrapped up the idols… It was at this time that they chose officials, the Chacs to assist the priest, and he prepared a large number of little balls of fresh incense… so that the fasters and abstainers might burn them in honor of their idols… New Year’s day having then arrived, all the men assembled in the court of the temple… The Chacs seated themselves at the four corners, and stretched from one to the other a new cord, within which were to enter all those who had fasted, in order to drive out the evil spirit… [T]he Chacs kindled the new fire, and lighted the brazier… and they burned incense to the idol with new fire.

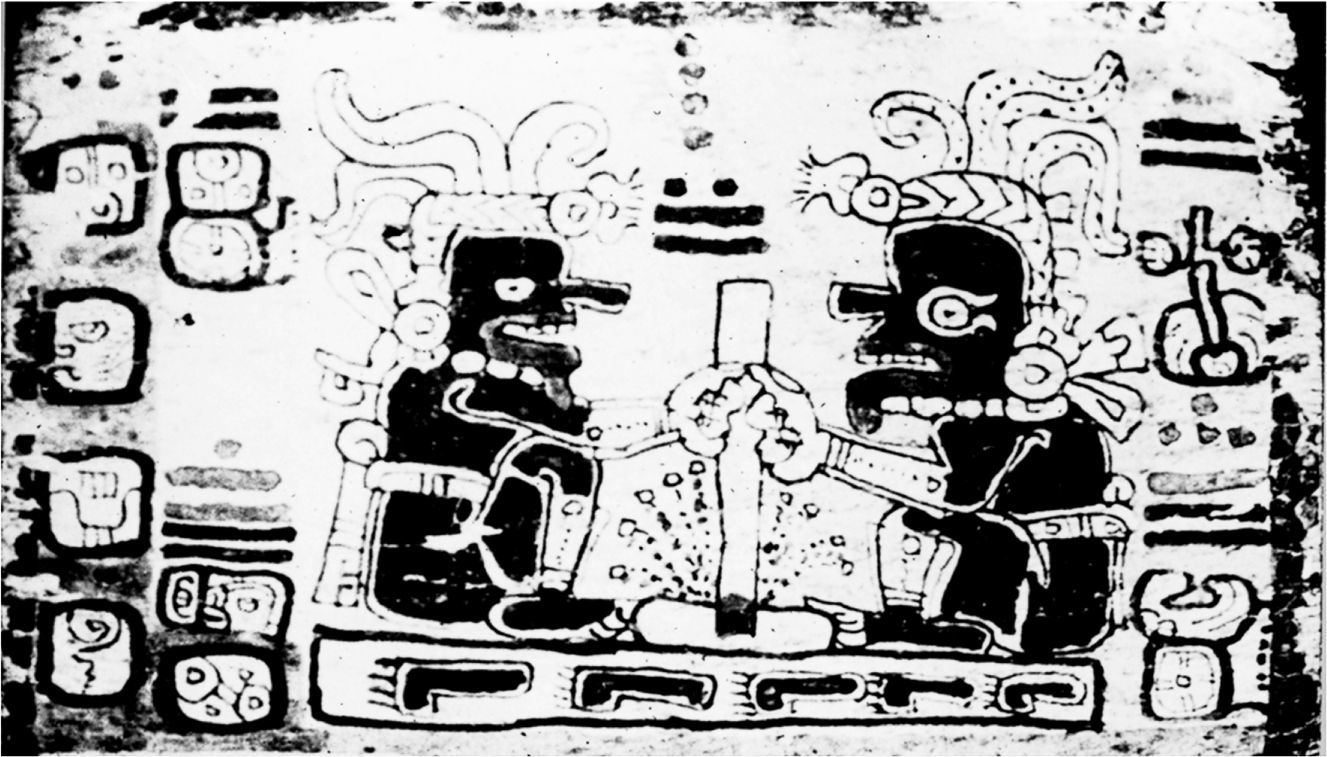

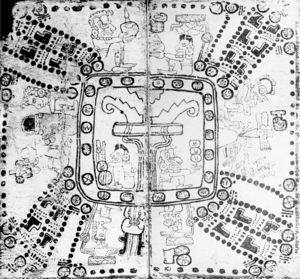

As scholars have previously noted, the almanac on page 19b of the Madrid Codex (figure 4) shows a variant of the ritual described by Landa of stretching a rope around the corners of the temple courtyard (in this instance, the rope is being used to perform a loodletting ritual, which is another ceremony that Landa describes [Tozzer, 1941: 114]). Some of the elements of importance in the scene include the four ritual participants (Landa’s “Chaaks”), plus the “priest” (Itzamna); the temple or altar in the center of the scene, which is painted blue; and the turtle with the yax glyph pictured next to Itzamna. This can be identified as the “idol” that Landa describes being worshiped during Muluk new year ceremonies, called Yax Cocah Mut (yax, ‘first’, kok, ‘turtle’, ah mut, ‘omen’; see Knowlton and Vail, 2010 and Vail and Hernández, 2013).

Renewal rituals associated with 4 Ahaw on Madrid Codex 19b. After De Rosny (1883)

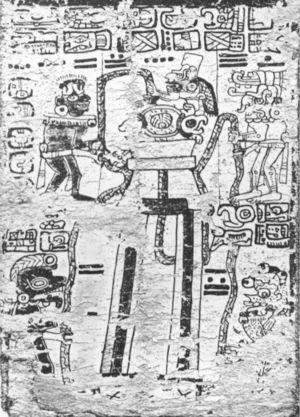

Several of the deities from Madrid 19b are also pictured drilling new fire in the almanacs on Madrid pages 38b, 38c, and 51a, including the black merchant deity (God M) and Itzamna. As we discuss below, this is one of the rituals associated with the annual renewal ceremonies of the contemporary Ch’orti’ Maya.

Ch’orti’ Renewal RitualsAmong the Ch’orti’ of southeastern Guatemala and western Honduras, creation symbolism is integral to annual agricultural ceremonies. The information concerning these rituals derives mainly from the work of the Swiss ethnologist Raphael Girard, who focuses on rites performed at Quezaltepeque in the early twentieth century (Girard, 1949, 1962, 1966). Additional information appears in the work of Fought (1972), López and Metz (2002: 206-9), and Wisdom (1940). More recent work by Kufer and Heinrich (2006) supplements, and largely confirms, the data gathered by Girard.

At Quezaltepeque, the confraternity of Saint Francis the Conqueror is responsible for the agrarian cult, which includes rainmaking activities. Ritual specialists, a married couple entitled Padrino and Madrina Titular (Godfather and Godmother in Office), carry out their duties for a period of two years, while five younger men called Adornantes or “Decorators” assist the elders (Kufer and Heinrich, 2006: 388). The rituals are directed toward the fertility deities Saint Francis and the Virgin Mary, whose offspring is the Maize God (Girard, 1966: 22).

The agricultural cycle is structured according to a count of 260 days, starting on February 8 and ending on October 25 (Girard, 1962). February 8, a date associated with cosmic renewal and Creation, is marked by a pilgrimage to the sacred pool of El Orégano, located to the west of town. This body of water is recognized as a portal to the underworld, as well as a cosmic basin from which clouds take their water. At this sacred place, the ritual participants prepare a mesa, or ritual feast for the gods. Five gourds of chilate, a ceremonial drink made from maize and cacao, are placed upon a cloth spread on the ground. Arranged in a quincunx, these offerings are viewed as a “payment” to the spirits of the four directions to withhold wind and rain until the fields are ready for planting (Fought, 1972: 416). After returning to the temple of Saint Francis in Quezaltepeque, the elders capture malevolent winds, which are stored in sealed jugs. These will remain beneath the saint’s altar until the agricultural season is over. A set of stones gathered previously at the El Orégano pool is arranged atop the saint’s table, and four additional stones are placed at the corners of the temple. Finally, a feast is served on an adjacent table.

Following these Creation rituals, the fields are cleared of vegetation, concluding by the time of the vernal equinox (March 20). Activity begins again on Good Friday, when, following ceremonies in the church, a mesa is set in the temple of Saint Francis. On the next day, the padrino extinguishes the temple fire and starts a new fire, from which the domestic hearths are relit. Girard (1962: 66) mentions that in Chiquimula, this ritual is conducted using the ancient technique of drilling, in which a stick is placed in a socket on a board and then spun between the hands until sparks appear. This rite announces the time when the fields should be burned, thereby feeding the clouds that bring rain.

The major ritual of the rain cult (the “fetching of the rainy season”) starts on April 22, just before the rainy season is supposed to begin (Girard, 1962: 81; Kufer and Heinrich, 2006: 388-97). A pilgrimage is made to the sacred spring that is the source of the Conquista River, located near the hamlet of Azacualpa in the municipio of Quezaltepeque. This spring is associated with the crucifixion of Christ and the transformation of his flowing blood into the primordial rain (Girard, 1962: 225). It is also the abode of the Noh Chih Chan, a great serpent that guards the water (Girard, 1962: 95). Sacrificial offerings encourage this deity to release the moisture that transforms into clouds that bring rain to the fields. In the clearing near the spring, the Padrino dedicates a cross that is inscribed with his name adjacent to the crosses of his predecessors. All crosses are then adorned with conte leaves, and candles are lit before them. Meanwhile, at the temple of Saint Francis, the women prepare food (tamalitos) to feed pilgrims to the shrine and replace the dry altar adornments with fresh greenery (conte leaves and green coconuts).

The next day (April 23), the women prepare additional ceremonial foods, including chilate, tamales, bean empanadas, and maize tortillas. In the evening, a procession departs for the sacred spring. According to Girard (1962: 86), this locale represents the underworld; and on this night, the men recite prayers in order to open a portal between the two mountains that block its entrance. Upon reaching the spring late at night, a ritual meal is spread on the ground and consumed by the specialists. The padrinos pray, burn incense, and then sacrifice a young female turkey to the Noh Chih Chan by drowning. The men allow the water current to suck the bird’s body into the pool. Afterward, chilate is poured into the spring, followed by the blood of a male turkey (Kufer and Heinrich, 2006: 397). When Girard made his observations, these offerings were placed in a pit in the earth rather than the sacred spring itself, from which drinking water was being drawn (Girard, 1962: 92-3, 95).

On April 24, the altar of Saint Francis is fully adorned, and a canoe containing aquatic animals and water from the sacred spring is placed beneath it. Girard (1962: 110-111) states that this canoe symbolizes the navel or heart of the earth and is thus equivalent to the pit dug near the sacred spring. Its placement beneath the altar of Saint Francis associates this location with the underworld. At midnight, a mesa dedicated to the rain gods is set in the temple. The next night, and each night afterward until regular rainfall commences, the interior of the temple is sprinkled with water in order to induce the gods to send rain to the fields (Girard 1962: 112). Following this complex ritual sequence, men initiate the planting of the fields, accompanied by additional sacrifices of birds and chilate in holes dug in the milpa (Wisdom, 1940: 441-444).

The rainy season is officially inaugurated on April 30-May 1 by the zenith passage of the sun. According to Girard (1962: 79, 148-149), the Ch’orti’ conceive this event as the impregnation of the earth by the “fertility god” when he passes through the zenith at noon. To mark this date, they observe noontime shadows as well as astral phenomena, including significant positions of Orion, the “Cross of May”, and the Pleiades (Fought, 1972: 59; Girard, 1962: 78, 147). Shortly afterwards, on May 2, a mesa is set in the temple to Saint Francis. This is repeated every nine nights through the end of the rainy season. Each time, the greenery of the altar is refreshed, and chilate is poured to the four corners of the temple patio and under the altar.

Similar ceremonies of rainmaking and offerings to the earth may also occur later in the agricultural season, in association with the second planting of themilpa. This occurs around August 12 or 13, marked by the second solar zenith passage. However, these ceremonies are on a smaller scale than those held on the first zenith passage of the sun (Girard, 1962: 253-254). The rainy season rites conclude on October 25 with the “turning of the mesa,” when the ritual vessels are emptied, washed, and inverted, and the altar adornments are replaced with red, yellow and purple flowers, symbolizing the dry season.

In summary, the contemporary Ch’orti’ rain cult involves the coordinated activities of ritual specialists at locations both at the cult temple and in the wilderness. Rites emphasize the use of sympathetic magic, such as scattering water and pouring chilate or blood, as well as ritualized exchange involving the offering of candles, incense, lavish meals, and sacrificial birds. The main purpose of these rites is to provide sustenance to the rain gods. In exchange, the gods are expected to supply regular rainfall during the agricultural season. The overall schedule for these rites may be recapitulated as follows:

- •

Feb. 8: mesa at sacred pool; capturing of winds in temple; stones set in temple (Creation).

- •

Saturday of Holy Week: new fire drilled.

- •

April 22: dedication of inscribed cross.

- •

April 23: ritual meal at sacred spring, sacrifice of fowl and chilate at spring.

- •

April 24: altar fully adorned; temple watered.

- •

April 30-May 1: first zenith passage of the sun.

- •

May 2: mesa set in temple to be renewed every nine days.

- •

October 25: “turning of the mesa”, closing the rainy season rites.

The Ch’orti’ agricultural ritual cycle emphasizes specific elements which are also found among the Yucatec Maya. The Ch’orti’ extensively evoke foundation events, initially through the quincunx of stones that is erected on the altar in the Saint Francis temple and the four stones that are set at the temple’s corners. The same pattern is later refected in the arrangement of mesas (ritual meals) at sacred locales in the landscape, particularly at the spring that is the source of the Conquista River.

Acts of sacrifice are fundamental to the aims of the ritual cycle. These mainly take the form of food offerings placed on mesas in the temple of Saint Francis, as well as meals prepared at the sacred spring. Incense and candles are also offered. Most dramatic is the offering of male and female turkeys at the sacred spring.

The Ch’orti’ ritual cycle involves complex and repeated petitions to deities of rain and the earth. Sacrifices to the serpent Noh Chih Chan are made at the sacred spring. Mesas and prayers are offered to the rain gods at the El Orégano pool and in the temple of Saint Francis throughout the growing season. In addition, liquid offerings to the spirit of the earth are poured into pits dug in fields or the sacred spring. The vertical movement of these offerings replicates the cosmic act of impregnation of the earth by the sun as well as the descent of rain to the earth. The cacao drinks that are used extensively in these rituals are specifically associated with the cold, moist rainy season (Kufer and Heinrich, 2006: 401-405).

Finally, the Ch’orti’ agricultural rituals also emphasize sacred watery places. These include the El Orégano pool and the sacred spring, believed to be rainwater basins and sacred underworld locations. The ritualists attempt to transform the temple of Saint Francis into a realm attractive to the rain deities by sprinkling it with sacred water and by maintaining a water-filled canoe placed beneath the altar.

ComparisonsA number of specific parallels can be noted between the ceremonies documented among the contemporary Ch’orti’ of Quezaltepeque and those depicted in the Maya codices and described by Diego de Landa (Tozzer, 1941). The first set of comparisons involves the almanac on Dresden pages 31b-35b, which has links to the mesa celebrated at the sacred pool and the drilling of new fire. Comparisons can be made between the four paired frames showing Chaak emerging from a cenote —and Ch’orti’ rituals at the sacred spring of El Orégano, which also involve the setting of four stones in the temple. Among the Ch’orti’, these events take place on February 8 and are undertaken to replicate the original events of creation and ensure cosmic renewal. The pool where the rituals take place is believed to be a portal to the underworld, much as is true of the serpent cenotes in the Dresden almanac; it likewise serves as a place of evaporation from which clouds derive their water. This function is made explicit in the Dresden almanac by the portrayal of Chaak rising from the cenote/serpent stone with his upraised axe. His presence here serves to symbolize the waters that will rise into the sky and fall as rain during the upcoming rainy season.

It is also significant that the Ch’orti’ ritual involves the placement of a set of stones from the sacred pool on the saint’s altar, and the setting of four stones at the corners of the temple. These can be compared to the “stones” pictured and described in the text of the Dresden almanac, which likewise have a connection with the stones set at the time of creation according to Classic period Maya texts such as Quiriguá Stela C (figure 5). They can also be compared to the ah kaan tun, or serpent stones, pictured on Dresden 25c-28c, which serve as the focal point for the rituals undertaken by the deities of the incoming year. This provides another link among these objects, Chaak, and ceremonies to call the rains.

Various explanations have been offered for the frames that show Chaak holding torches on D. 31b-35b, including their relationship to a set of rituals involving the lighting and extinguishing of fres by the “Burners” (see Vail and Hernández, 2013). One possibility that has not been previously considered is that the torches held by Chaak relate to the drilling of new fire associated with agricultural renewal rituals, as documented among the Ch’orti’ (see previous discussion). After new fire was drilled (as, for example, on Madrid 51a [figure 6]), torches were lit so they could be used to reignite the fres at each of the temples and houses.

The drilling of new fire on Madrid Codex 51a. After Gates (1911)

A number of other specific inferences can be made by comparing the events associated with late April among the Ch’orti’ and the Dresden yearbearer pages, although the seasonality of the two sets of rituals differs.3 Nevertheless both were clearly developed with the object of petitioning the rain deities and ensuring a bountiful harvest, suggesting that a comparison of specific details is warrented.

In the Quezaltepeque area, April 22 is the day associated with “fetching the rainy season”; specific events include sacrificial offerings to the serpent Noh Chih Chan to encourage him to feed the rain clouds, the dedication of the cross and its adorning with conte leaves, and the lighting of candles before the crosses. The lower register of the Dresden yearbearer almanac has a number of specific parallels to these events, including the emphasis on Chaak and serpents, which can be associated with the Noh Chih Chan and rainmaking ceremonies. Likewise, the dedication of the cross in the Ch’orti’ ritual can be compared to the setting up of the “tree” in the Dresden almanac, which is decorated with leaves (like the crosses). Instead of burning candles before the trees, however, the burning of incense is portrayed.

On the following day in the Ch’orti’ ceremony, a ritual meal is consumed at the spring (note the food offerings on Dresden 25c-28c), incense is burned, and a young female turkey is sacrificed to the Noh Chih Chan. In the Ch’orti’ ritual, the turkey is sacrificed by drowning, whereas decapitation is the method depicted in the Dresden almanac. The canoe that is set up under the altar on April 24 in the Ch’orti’ ritual may have parallels with the cenote imagery pictured in the upper register on pages 27 and 28 of the Dresden almanac. Like the canoe containing sacred water from the spring, cenotes also symbolize the “navel” or heart of the earth and provide a means of accessing the underworld. Moreover, the mesa to the rain gods set in the temple at midnight in the Ch’orti’ ritual calls to mind the offerings of food placed before the deities of the outgoing year in their temples in the middle register of the Dresden almanac.

The Ch’orti’ ritual incorporates the beginning of the rainy season, which is associated with the zenith passage of the sun on April 30. This event is not represented in the Dresden yearbearer almanac, given its focus on events falling later in the year.

The Madrid yearbearer almanac, like that in the Dresden Codex, refers to dates in August and July in the tropical year (because the haab’ is .2422 days shorter than the tropical year, yearbearer dates recessed by approximately one day every four years over the course of the tropical year). However, unlike the Dresden almanac, it appears to show a range of activities that fall in different months of the year, as suggested by the haab’ dates scattered among the iconography (see Hernández and Bricker, 2004). Activities that are important include planting (in Yucatán, initial planting of the maize fields would have occurred in late May or early June, with a re-planting taking place several weeks later), feasting, the lighting of fres, and bloodletting rituals. Each of these activities, as previously noted, has correlates with the agricultural renewal ceremonies of the Ch’orti’. The planting of seeds using a digging stick on M. 34a-37a recalls the Ch’orti’ belief that the zenith passage of the sun involves the impregnation of the earth by a fertility god during the sun’s noontime zenith transit. Additionally, the hieroglyphic texts accompanying the Madrid yearbearer almanac include references to the four color-directional clouds, which evoke the sacrifices made to the Noh Chih Chan so that they would transform into the rain clouds.

Final considerationsLike contemporary Ch’orti’ agricultural renewal ceremonies, the prehispanic renewal rituals, celebrated at the transition from one year to the next, also involved the movement of ritual specialists from temple locations within the community to sacred, watery places outside the confines of the community. Both sets of rituals incorporate sympathetic magic, such as the scattering and burning of incense to induce the rains, and are characterized by similar types of offerings including incense, food and drink, and sacrificial birds. For the prehispanic Maya as well as the Ch’orti’, the main purpose of these rites involved providing sustenance to the rain gods, who are expected in return to supply plentiful rainfall to ensure the success of the maize and other crops.

Although substantial differences characterize contemporary Ch’orti’ rituals of agricultural renewal and the yearbearer rituals undertaken by the prehispanic Maya, what is evident is that the two share a complex of activities and symbols that can be recognized as structurally equivalent despite the many changes that have occurred during the more than 500 years since the Spanish first set foot on the soil of Mesoamerica.

We follow Thompson (1972: 90) in suggesting that the pictures and hieroglyphic captions on pages 26c and 28c were transposed by the scribe. In the discussion that follows, we associate page 26c with Itzamna and the north and page 28c with K’awil and the south.

Note that they are marked with the “Kawak” or ‘stone’ glyph (T528).

Yearbearer ceremonies like those depicted in the Dresden almanac fell in mid-August during the early 15th century. In this respect, their timing corresponds much more closely with the rituals performed in conjunction with the second zenith passage (i.e. on August 12-13) in the Ch’orti’ area. A detailed comparison however, suggests a closer correspondence between the events depicted on Dresden 25-28 and the April rituals, as discussed below.