Pese a la estructura inusual de las inscripciones monumentales de los antiguos mayas, que se escribían como si los glifos se reflejaran en un espejo, todavía falta un análisis a fondo de la forma de estos textos. Después de analizar 11 monumentos, propongo que las inscripciones de forma especular constituían metáforas visuales cuyo significado estaba vinculado con el significado ritual de los espejos como símbolos del poder político y religioso. Además, el significado metafórico de estos textos influía en cómo el espectador entendía y se relacionaba con el monumento. Con base en evidencias de la arqueología, la epigrafía, la iconografía, la lingüística y la ciencia cognitiva, sostengo que la forma especular de estas inscripciones extendía la participación ritual del espectador maya para ponerlo en contacto con lo sobrenatural. Con este estudio espero inspirar más investigaciones sobre la relación entre forma y función en los monumentos de los antiguos mayas.

In spite of their aberrant orientation, ancient Maya monumental hieroglyphic inscriptions that were carved in mirror-image have been relatively understudied by scholars with respect to the significance of their shared form. Based on examination of eleven such monuments, I propose that mirror-image inscriptions constituted visual metaphors related to the ritual importance of artifactual mirrors as symbols of political and religious power. Furthermore, the metaphorical significance of these texts influenced the viewer’s interpretation of and interaction with the monument. Using evidence from archaeology, epigraphy, iconography, linguistics, and cognitive science, I argue that the mirror-image form, of these monumental inscriptions, extended ritual participation beyond the monument’s protagonist to the ancient Maya viewer through contact with the supernatural. With this work, I hope to begin to fill a significant gap in ancient Maya studies and offer an alternate perspective on the relationship between monumental form and function.

Numerous ancient Maya monuments contain individual mirror-image glyph blocks whose component hieroglyphs face against the standard left-to-right reading order, such as Seibal, Stelae 3 and 7 (see Graham, 1996: 7, 25), Caracol; Stela 1, from Chichén Itzá (Ruppert, 1935: 280, see figure 167), a fragment from La Entrada region known as the Monster Muzzle (Schele, 1991a: 211, see figure VII-30: 1), and a monument from the Usumacinta region (see Robertson, Rands and Graham, 1972: Pl. 78). Sequences of multiple mirror-image hieroglyphs are found on other media from the Maya realm, most on notably ceramics (e.g. Kerr, n.d.: 1333, 1507, 4925) and in the codices (Severin, 1981: 21; see Lee Jr., 1985: 156-157), and they also appear on monuments from other Mesoamerican cultural groups (see Kaufman and Justeson, 2001: 34-74).** In this study, I focus my analysis on the eleven ancient Maya monumental inscriptions that I was able to identify as featuring at least two successive glyph blocks whose components have been systematically reversed.1

Scholars have recently turned more attention to the interplay between the structure and significance of ancient Maya monuments, with respect to both their inscriptions and their iconography. Nonetheless, few researchers have thoroughly addressed the importance of variability in textual form and the relationship of such variability with the use of different iconographic structures (e.g. Miller, 1989: 182). Theories to explain alternate orientations of visual motifs or hieroglyphs are often functional, assuming that such discrepancies reflect personal artistic expression or spatial constraints (e.g. Foster, 2002: 280; Justeson, 1989: 28-29; Kerr, 2007; Palka, 2002: 432).

Some of those who have attributed symbolic connotations to the reversed structure of mirror-image texts have posited a cosmological or political meaning behind the use of alternative inscriptional structures (e.g. Robicsek, 1975). Additional theories have concentrated on the left/right symbolism as an expression of beliefs surrounding cosmological and social ordering (e.g. Akers, 2008; Lough-miller-Newman, 2008: 40; Palka, 2002), according to which the body orientation of individuals depicted in iconography, as well as the direction in which any associated hieroglyphs were read, reinforced the social, ritual, and/or political significance of the monument. Monumental structure has thus been related to cultural messages concerning gender (e.g. Joyce, 1996: 174; McAnany and Plank, 2001: 116-117) and cardinal direction (e.g.Foster, 2002: 256; Joyce, 1996: 174). Further discussion of the orientation of the iconography on these monuments with mirror-image texts is beyond the scope of this brief report, however; for more information the reader is referred to Palka (2002) and Loughmiller-Newman (2008: 37).

One widely-supported theory asserts that reversed monumental inscriptions were intended to be read from a position behind the monuments on which they were carved, presumably by gods and other supernatural beings, including the ancestors, who would have been able to read through stone (Schele, 1991b: 70; Schele and Freidel, 1990: 326–327; Schele and Miller, 1986: 187; Steiger, 2010: 53). Similarly, others argue that these texts reflected the spatial context of the recorded events (Schele and Miller, 1986: 49) or the position of the viewer relative to the monument (Houston, 1998: 342-343; Jones, 1975: 91; Palka, 2002: 431-432).

Other scholars propose that mirror-image reversals indicated that the events and individuals recorded belonged to the underworld, “because the underworld is the mirror image of the world” (Baudez, 1988: 138; also see Palka, 2002: 438; Robinson, 2010: 1-2). Alternately, some interpretations posit that the mirror-image inscriptions visually represented the social position of the text’s protagonists (e.g.McAnany and Plank, 2001: 117; Schele and Miller, 1986: 107; Palka, 2002: 430; Viel, 1999: 386). Still other theories apply the possible social connotations of mirror-image inscriptions more generally and suggest that their reversed structures symbolized broader social phenomena, such as ceremonial contexts (Palka, 2002: 431), rather than relationships between specific individuals.

In spite of the diversity of these theories, their relatively narrow focus on the potentially supernatural, honorific, or symbolic functions and meanings of mirror-image texts fails to adequately address the aesthetic effect that reversed inscriptions would have had on their human viewers. The display of these inscriptions as visible features of monumental architecture indicates that the reversal of these texts had more worldly intentions and impact. Even if these monuments were not always accessible to the general public, their texts were carved with the awareness that they would be viewed and interpreted by mortal audiences. The monument-makers would have been aware that reversed inscriptions would affect viewers differently than those oriented in the conventional direction.

I draw on evidence from epigraphy, archaeology, iconography, linguistics, and cognitive science for the significance of mirrors among the ancient Maya to argue that their unusual form incorporated the viewer into the ritual activities recorded on the monument by presenting what appeared to be a reflection of an alternate reality. By encouraging the viewer to redefine his or her own position relative to the monument, the mirrored structure engaged the viewer as a ritual participant in the events communicated by the monument by facilitation communication with the supernatural. This orientation that was shared between these monuments was a manifestation of what Washburn (1999: 553) denotes as “metaphorical symmetry.” The texts mirrored across a vertical axis conveyed culturally significant information through their structure as a kind of “visual metaphor” that both reinforces and expresses a certain way of conceptualizing a particular aspect of human existence (Washburn, 1999: 553; also refer to Lakoff and Johnson, 2003). This message would have been conveyed through juxtaposition of the mirrored texts with other glyphs oriented from in the usual left-to-right orientation, both on the same monuments and on other public works.

The mirror-image structure of the hieroglyphsGiven the undeniable effect of this change in orientation on the monumental inscriptions and its viewer, it seems appropriate to begin with an analysis of the expressions and ramifications of the intentional reversal on the level of each text’s most basic linguistic component: the individual hieroglyph. Even a cursory glance through the Maya hieroglyphic corpus reveals that many Maya hieroglyphs are characterized by vertical bilateral symmetry along a vertical axis, either in their external form, internal components, or both.2 Such glyphs include both phonetic hieroglyphs, like pa (T586) and lo (T580), as well as logographs, such as AKB’AL (T504) and SAK NIK (T179).3 A few head variants are also vertically symmetrical, such as T547 and T542b (see Macri and Looper 2003:150). The tendency towards orientation along a central, vertical axis may be part of a broader Mesoamerican cultural preference, as suggested by Taube’s (2011: 100) observation that Teotihuacan writing tends to be composed in vertical columns oriented in the center of the surface on which they were inscribed. The apparent preference for vertical bilateral symmetry in the glyphs may also be a learned trait that reflects the fact that vertical bilateral symmetry is particularly significant in human identification of objects and is also more easily recognizable to humans than horizontal and other forms of symmetry (Washburn and Crowe, 1988: 21-23).

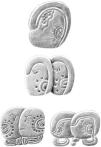

Scholars have recognized a select few mirror-image forms as standard elements in the Maya hieroglyphic corpus (see Macri and Looper, 2003: 34; Thompson, 1971: 41). These include hieroglyphs consisting of two components mirrored across a vertical axis, such as the phonetic hieroglyphs for sa (T630), ma (T74), and nu (T106) (Macri and Looper, 2003: 34-35). Some hieroglyphs assume a different semantic and phonetic meaning when reversed, such as a rare head variant for the syllable wa (PX3) and the head variant na (T1000a) that denotes a mother or feminine attributes (figure 1).

The transcription of other hieroglyphs may vary according to whether they consist of a single or a mirrored double component, as in the case of the hieroglyph T528 (figure 2a). Alone, the glyph is commonly glossed as the syllabograph ku. When T528 is doubled, however, the resulting glyph carries the phonetic value pi, regardless of whether the two components are facing in the same (figure 2b) or in opposite directions (figure 2c) across an invisible vertical axis. Such examples indicate that the arrangement of these hieroglyphs’ internal elements along a vertical axis may not have been significant in communicating linguistic meaning. Comparatively, orientation with respect to the horizontal axis seems to be more significant semantically and phonetically (John Henderson, personal communication, 2011). Within glyph blocks, many hieroglyphs were often rotated to best accommodate the other glyphs, especially when functioning as grammatical affixes or phonetic complements. Yet they appear to have retained their original significance regardless of their orientation, a feature noted by Thompson (1971: 38) among affixes. The variation in dictionary entries showing T102 as a post-posed phonetic complement for WINIK-ki (see Montgomery, 2002: 271) with no apparent change in meaning, for instance, suggests that the orientation of T102 ki was flexible.

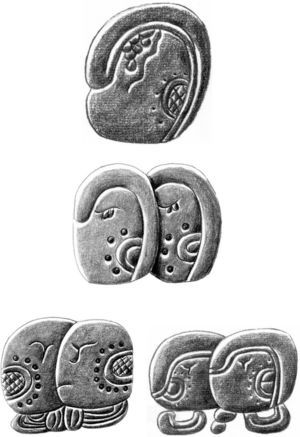

Evidence for variability in orientation can also be found in logographic hieroglyphs, including T168, one of the many logographs for AJAW. Montgomery (2002: 27, 29) lists multiple entries of T168 that demonstrate that its two side-by-side components can be flip-flopped with no apparent change in the hieroglyph’s phonetic or semantic reading. Furthermore, the orientation of T168 is not always constant within the same inscription: the manifestations of T168 in the Yaxchilán emblem glyphs on the unprovenienced Kimbell Lintel are written differently, in spite of the fact that they occur directly next to each other (figure 3). This alternation in the structure of T168 is also apparent in the unreversed text on the provenienced Yaxchilán Lintel 10 (see Graham and von Euw, 1977: 31, glyph blocks A7, B3 and F3).

Such discrepancies that occur even between adjacent glyph blocks indicate that the ancient Maya hieroglyphic system allowed for considerable flexibility in the vertical orientation of individual hieroglyphs. Instead, the vertical arrangement of hieroglyphs with respect to one another, both within and between glyph blocks, is more essential to the reading and interpreting glyphic passages. The variation possible in the orientation of the individual hieroglyph would have allowed Maya monument-makers the freedom to produce entire hieroglyphic passages in mirror-image without necessarily changing the semantic or phonetic content of the text.

Examination of this study’s corpus of eleven reversed monumental texts reveals that, because many hieroglyphs are vertically symmetrical, it is often impossible to determine whether or not each glyph in these inscriptions was rotated individually. Interestingly enough, however, closer inspection of those hieroglyphs whose external form and/or internal elements are vertically asymmetrical revealed that these monumental inscriptions were not reversed as thoroughly as one might have expected. Each mirrored inscription contains at least one un-reversed glyph. Besides the left side of Uaxactún Stela 20 (see Graham, 1986: 181-185) and the Copán fragments discovered near Temple 11 (see Schele and Grube, 1991: Figure 2), which are too incomplete to permit analysis as self-standing texts, all of the mirrored texts in this study’s corpus contain at least one anomalous glyph whose left-to-right directionality contradicts the reversed orientation of the rest of the text. Again, this suggests that the orientation of each individual hieroglyph was not necessarily significant in communicating either the content of the text or the meaning of the monument’s mirror-image structure. When creating mirror-image texts, the monument-maker may have instead focused on altering the typical relationship among the glyphs, both within and between glyph blocks.

The occurrence of left-to-right oriented hieroglyphs in these mirror-image texts may also reveal significant connections between the unmirrored hieroglyphs. One of the most prominent examples occurs in the reversed inscription on Yaxchilán Lintel 25, in which the logograph T714 TZAK occurs in its usual orientation (figure 4a).4 Although this feature has not escaped the notice of modern scholars (e.g.Winters, 2007), it has not been examined in any detail in their analyses of the text. While it would be easy to dismiss this disparity as an error, the monument-maker may very well have intentionally left T714 in its usual orientation. The same logograph also appears in the left-to-right oriented text on the lintel’s front edge, for which reason the monument-maker would have been less liable to mistakenly carve the glyph in the same way in both texts. Also, it is unlikely that a reversed image of T714 would have created confusion with other glyphs, since scholars have yet to identify another Maya hieroglyph that depicts the palm side of a grasping right hand (see Boot, 2010: Figure 8).

(a) T714 TZAK as it occurs on the underside of Yaxchilán Lintel 25. Note that it has not been mirrored along with the rest of the text in which it occurs. (b) The mirrored form would presumably look like this version of T714, which Graham and von Euw (1977: 56, glyph block B1) include in their drawing that re-orients the mirrored text on the monument’s underside in the standard left-to-right reading order. Drawn after Moisés Aguirre based on the Graham and von Euw’s drawing (1977: 55-56, glyph block B1).

However, mirroring T714 may have involved more than simply reversing the position of the fingers, as do Graham and von Euw (1977: 56) in their reproduction of the mirrored text on Lintel 25 in the standard left-to-right reading order (figure 4b). If the monument-maker had considered the mirror image of T714 to be the representation of a hand as viewed from behind, he or she may have been faced with the conundrum of completely changing the glyph form in order to depict the backside of a human hand, an option unattested to on Lintel 25. Alternately, the monument-maker could have drawn a grasping right hand, rather than a left hand, to convey the mirror-image structure.

Relatively few hand glyphs appear in the mirrored texts examined for this study, but significantly, those that do seem to have all been left in their standard orientation, even though the surrounding glyphs have been mirrored. Palka’s (2002) discussion of the cultural and social salience of left- and right-handedness among the ancient Maya suggests that the creator of Lintel 25 may have intentionally depicted T714 TZAK in its usual orientation in order to preserve the connotations associated with the left hand, rather than depicting a right hand (also see Winters, 2007). Similarly, the individual(s) responsible for the creation of the Kimbell Lintel may have recorded the standard version of K’INICH-ni within a string of mirrored hieroglyphs in order to emphasize the right-handedness of the image (see Mayer, 1980: Plate 36; cf. Montgomery, 2002: 152). There are also rare instances in which the monument-maker mirrored the individual hieroglyphs, but not the relationship of the glyphs to each other. In the mirror-image inscription on the West door, south panel of Temple 11, for instance, the monument-maker still depicted the focus marker T679 i to the viewer’s left of the verbal phrase u-ti in glyph block A3, although the mirrored structure would have presumably dictated its placement to the side of the block to the viewer’s right (Schele, Stuart and Grube, 1989: Figure 13).

Generally, however, the relationship between the glyphs within glyph blocks and the placement of glyph blocks within the text seem to have been more thoroughly mirrored in the reversed texts analyzed in this study than the individual hieroglyphs themselves. This evidence indicates that Maya monument-makers were more concerned with depicting the reversed relationship of the hieroglyphs to each other, rather than necessarily reversing each hieroglyph individually when creating mirror-image monumental inscriptions. In some cases, they may have intentionally left hieroglyphs unreversed to avoid connotative changes in their meaning. Additionally, ancient Maya monument-makers may have used certain hieroglyphs that, because of their vertical bilateral symmetry, for instance, were less arduous to reproduce in mirror image or were more easily recognizable by the viewer. However, the extremely thorough statistical analysis that would be needed to investigate patterns in glyph usage between mirrored and non-mirrored texts is beyond the scope of this study. In addition, such a data set would ideally include more than the eleven monuments that I was able to identify for this study as containing at least two successive mirrored glyph blocks.

The preceding epigraphic analysis generally indicates that ancient Maya creators of mirror-image monumental texts were more concerned with reversing the relationship of the hieroglyphs to one another than with producing an individual mirror image of each hieroglyph. Yet perhaps the more important question concerning the relationship between the reversed inscriptions and any accompanying iconography addresses not whether they share a mirror-image orientation, but rather how the text’s reversal affected the meaning of the entire monument. In order to more thoroughly examine the significance of and motivation behind the creation of these mirror image texts, including their effect on the monument as a whole and the viewer’s relationship with it, I will analyze the cultural value of mirrors among the ancient Maya and apply any relevant insight to the traditionally more epigraphic study of mirror-image monumental texts.

Mirrors in archaeologyEven before the rise of the Maya states, other ancient Mesoamericans were making mirrors by working and polishing the surfaces of various natively-occurring minerals, including magnetite, ilmenite, pyrite, obsidian, mica, and hematite (Scarborough, 1998: 151; Taube, 1992a: 169 and 1992b: 33). Taube (1992b: 34) suggests that the trade in obsidian between Teotihuacan and the Maya also resulted in the exchange of ideas concerning the ritual function of the mirrors created from this material. Ancient mirrors ranged in size from small, portable reflectors to large “mosaics” of polished minerals pieced together in a wooden or ceramic frame into a unified mirror, whose non-reflective sides were often enhanced by additional embellishment (Pendergrast, 2003: 26; Reents-Budet, 1994: 83; Taube, 1992a: 180).

Although they may have been used domestically, the polished faces of mirrors would have been especially important in ritual contexts in ancient Mesoamerican societies, including that of the Maya (Taube, 1992a: 170). Mirrors likely represent only one category of the objects that the ancient Maya valued for their shininess (Healy and Blainey, 2011: 238). However, a key distinction between mirrors and other objects that reflected light, such as celts and polished shells, lies in their reflective properties: mirrors reflect at least a distorted image of the scene before them, whereas celts simply reflect light without reproducing an image (Saunders, 1988: 2). Because of the direct link between the images produced by mirrors and the structure of the texts discussed in this study, as well as the problem of distinguishing between images of mirrors and celts, (Healy and Blainey, 2011: 234; Stuart, 2010: 291), I will focus on mirrors here, without further discussion of other shiny objects used by the ancient Maya that do not reflect such a recognizable image.

Although some materials produced more distorted reflections than others, all mirrors would have been prized for their ability to shine and to produce images by redirecting light (Saunders, 1988: 2). Their highly reflective properties are thought to have contributed to associations between mirrors, fire, and the sun (Taube, 1992a: 186, 193). Throughout Mesoamerica, mirrors may have also been associated with eyes, especially those of felines, because of their similar reflective abilities (Saunders, 1988: 11; also see Milbrath, 1999: 184, 198). In spite of the iconographic evidence for using mirrors to aid the viewer in dressing and self-preparation (e.g. Kerr n.d.: K764, K4096), the unusual physical properties of mirrors rendered them particularly valuable for their social and ritual functions, particularly in scrying.

Evidence from archaeological, iconographic, and ethnographic studies indicates that mirrors were considered windows that facilitated communication with and possibly even movement between the human and otherworldly realms, whose inhabitants included the gods and the ancestors (Foster, 2002: 166; Healy and Blainey, 2011: 240; Looper, 2003: 72; Taube, 1992a: 194-195). The ritual use of mirrors for gazing into the divine realm was common to many ancient Mesoame-rican cultures (Taube, 1992a: 181, 1992b: 33); indeed, some theorize that ancient Maya use of mirrors in the Early Classic alludes to ties with Teotihuacan (Nielsen, 2006: 3; Taube, 1992a: 172).

Mirrors may have thus become associated with caves, which were also considered to be access routes into the dominion of the divine (Taube, 1992a: 194-195). Some ancient Maya scenes depict the deceased returning to this world through a mirror to reunite with their ancestors (Schele and Mathews, 1999: 225), implying that mirrors, like caves, may have been additionally associated with rebirth and the renewal of life (Looper, 2002: 193). In this context, it is important to note that Yaxchilán Lintel 25 and the Copán panels were originally installed directly in or in close association with doorways; the unprovenienced Chilib fragment has also been described as a “fragmentary doorway column” (Mayer, 1995: 15). The architectural placement of these monuments with mirror-image inscriptions may have referenced their symbolic ties to portals, and thus to the supernatural realm (Kathryn M. Hudson, personal communication, 2012).

The Maya may have also employed liquids as mirrors. The cultural link between water and mirrors also appears to have been part of a broader Mesoamerican tradition, as suggested by evidence for this connection among ancient inhabitants of Central Mexico (Taube, 2004: 144). The reflective surface of water may have been employed in ritual contexts similar to those in which mirrors were commonly used, including scrying (Healy and Blainey, 2011: 239; Taube, 1992b: 34). Ethnographic data records the indirect observation of eclipses by the modern Maya who were watching their reflections on standing water. Presumably, the ancient Maya also used mirrors and the reflective surface of standing water to observe these ominous astronomical phenomena (Milbrath, 1999: 27). Such usage further alludes to the employment of mirrors for astronomical purposes, possibly in relation to shamanistic practices (Schagunn, 1975). The iconographic record also contains depictions of ancient Mayas, often interpreted as elites, peering at their reflections on the surface of bodies of standing water (Scarborough, 1998: 148). Scarborough (1998: 151-152) proposes that the Maya elite constructed constructing reservoirs in association with many temples and elite residences in order to increase their prestige and authority by associating themselves with water symbolism in general. Besides water, liquid mercury may also have been valued for its mirror-like properties (Saunders, 1988: 20), although few examples of its use in a potentially ceremonial context have been found archaeologically (see Jones and Sharer, 1986: 27; Pendergast, 1982).

Perhaps more common due to its convenience and portability, however, was the ritual use of bowls containing reflective surfaces. Utilization of standing liquid in scrying is attested to in iconography from the Maya realm and from Teotihuacan, where the depiction of eyes in the middle of a bowl often denotes water (Taube, 2011: 98). Archaeological evidence also indicates that the ancient Maya sometimes placed mirrors in ceramic bowls (Smith and Kidder, 1951: 69), suggesting that the symbolic relationship between liquids and mirrors was reciprocal (Taube, 1992a: 189). Indeed, some illustrations depict individuals peering into concave, almost bowl-like objects, which scholars generally interpret as mirrors. These instruments are either carried by the viewers themselves (e.g. Kerr, n.d.: K505), propped up to face the viewer (e.g. Kerr, n.d.: K2914, K3203; Robicsek and Hale, 1981: Fig. 77b), or held up by another figure (e.g. Grube and Gaida, 2006: Abbildung 14.1; Kerr, n.d.: K4338, K5110; Reents-Budet, 1994: Figure 3.16). The various reflective surfaces contained in bowls may thus have fulfilled similar functions in ritual contexts.

Studies of Early Formative mirrors indicate that at least some pre-Maya societies were trading mirrors over long distances and that the use of these products was restricted to individuals of higher social status, although mirrors have been recovered from both domestic and ritual contexts (Pires-Ferreira, 1976: 323-324; Saunders, 1988: 12-13; Healy and Blainey, 2011: 231). Iconographic evidence indicates that mirrors may also have been used by individuals whose social standing was not the highest among those present (e.g. Kerr, n.d.: K1728, K2711). However, based on the contexts in which mirrors have been found, archaeologists tend to denote them as articles of prestige whose use in ritual contexts was associated with the ancient Maya elite (e.g. Coe, 1988: 227; Fialko, 2000: 145). The discovery of mirrors in direct association with ceramic censers, besides providing further indication that mirrors likely served an important ritual function, may also allude to a more practical use of mirrors as fire starters for either ritual or domestic purposes (Pendergrast, 2003: 26; Taube, 1992a: 186), although modern experiments have failed to replicate this usage (Schagunn, 1975: 293).

Mirrors have been recovered in other ritual contexts as well, including in a possible sweatbath (Looper, 2003: 72). Burial caches in particular have yielded significant quantities of mirrors, especially those found in tombs believed to contain high-ranking members of ancient Maya society (Coe, 1988: 227-228; Nielsen, 2006; Pendergrast, 2003: 26; Taube, 1992a: 170). In some of these burials, mirrors were found in direct association with human remains, suggesting that they were likely worn by these individuals at least in death, if not also in life (Smith and Kidder, 1951: 50). The placement of the mirrors on the small of the deceased individual’s back corresponds with iconographic evidence for the ancient Maya wearing mirrors, which are often shown as two-dimensional planes, affixed to their backs, foreheads, hips, chests (Schele and Mathews, 1999: 221-222; Smith and Kidder, 1951: Figure 42; Taube, 1992b: Figure 13), or headdresses (Taube, 1992a: 174, 181). The employment of mirrors as personal accessories is attested to among earlier Mesoamerican peoples (Clark, 1991: 20-21, Figures 5 and 6; Saunders, 1988: 16) and is corroborated by ethnographic observations from the time of the Spanish conquest (Markman and Markman, 1989: 97; Schele and Miller, 1983: 12). Images of mirrors affixed to shields and the bodies of warriors and of ballplayers have also led some to speculate that both the ancient Maya and Teotihuacanos symbolically connected mirrors with warfare and the ballgame, possibly through shared religious connotations (Nielsen, 2006: 6; Pendergrast, 2003: 26; Schele and Mathews, 1999: 213; Taube, 1992a: 172-174; see Foster, 2002: 197; Graham, 1996: 25; Robertson, Rands and Graham, 1972: Plate 78).

The many iconographic contexts in which mirrors appear in direct association with supernatural figures, rather than human-like characters, support scholars’ common association of ancient Maya mirrors with religious or cosmological connotations. Certain depictions of Maya deities include mirrors as part of the god’s apparel, often as an ornament worn on the forehead. God D, for instance, is frequently depicted with internal mirror elements (Foster, 2002: 166; e.g. Stone and Zender, 2011: Figure 9.1). God K or K’awil is also sometimes shown wearing (Grofe, 2006; Looper, 2003:41; e.g. Kerr, n.d.: 4354) or holding a mirror (Looper, 2002: 193), an image which Carlson (1981: 128) associates with rituals of political accession. K’awil and the Teotihuacán deity Tezcatlipoca, or “Smoking Mirror,” are often cited as two of several Mesoamerican deities who were associated with both mirrors and political power (Carlson, 1993: 248). Humans who wore forehead mirrors may have hoped to evoke an association between mirrors, the divine, and political authority that was shared across Mesoamerica (e.g.Schele and Freidel, 1990: Figure 4.25).

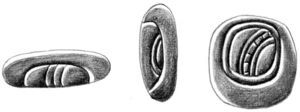

Mirrors in the hieroglyphsStylized depictions of mirrors have been incorporated into the ancient Maya hieroglyphic corpus as components of both phonetic and logographic signs. One of the most commonly cited examples of a probable hieroglyphic depiction of a mirror is T24 li/il, which can be used either phonetically or as a grammatical affix (Montgomery, 2002: 95, 161). Scholars have described this glyph as representing a mirror (Montgomery, 2002: 95, 161) or a reflective stone or celt (Macri and Looper, 2003: 275; Stone and Zender, 2011: 71), although differentiation between epigraphic and iconographic representations of the two artifact classes remains unclear (Healy and Blainey, 2011: 234; Stuart, 2010: 291). However, the parallel, curved lines within a partial circle that cut across only part of the width of T24 are distinct from the parallel lines drawn diagonally across the entire width of T245d and T245e, whose description as the image of a celt is supported by its proposed reading as a logogram for the same object (Macri and Looper, 2003: 275).

T24 and other similar hieroglyphs are usually identified as mirrors when they appear within other hieroglyphs, unlike T245d and T245e. Schele and Miller (1983: 10-12) even argue that the presence of other, variable elements associated with these mirror glyphs indicates that some of them linguistically represent obsidian mirrors in particular, as opposed to mirrors fashioned from other materials. Due to the difficulties modern scholars face when distinguishing between hieroglyphic and iconographic depictions of mirrors and other shiny objects, T24 and the related hieroglyphs discussed below will be generally referred to as mirror glyphs or mirror-like elements, with no further effort made here to distinguish between representations of mirrors, celts, and other reflective objects in the hieroglyphic corpus.

Several other hieroglyphs closely resembling T24 have also been cited as visual representations of mirrors. Like T24, both T121 and T617 also feature internal parallel lines that curve across some, but not the whole width of the glyph, and are encircled by a full or partial ring (figure 5). Various transcriptions and translations have been proposed for these two hieroglyphs that do not point to a clear semantic or phonetic relationship with T24. However, T24, T121, and T617 are the primary mirror-like elements that occur as internal components in other glyphs, a characteristic that suggests that they may have carried similar connotations. Most other mirror glyphs, such as T681, T712, and T88 (Macri and Looper, 2003: 244, 255, 273), either are variants of or contain these three primary glyphs as internal elements. Given the evidence linking them together, this study will refer to T24, T121, and T617 as the three main mirror hieroglyphs and will base much of the following analysis on observation of the role of these signs in the hieroglyphic corpus, including their relationship with other glyphs.

Certain anthropomorphically shaped hieroglyphs also contain stylized forms of T24, T121, or T617 as one of multiple internal components whose position within the glyph parallels previously cited evidence for mirror use among the ancient Maya. For example, certain hieroglyphs widely held to be representations of the Sun God, including T1010, display an infixed T617 on the god’s forehead or eye (Milbrath, 1999: 87, Figure 3.7f). Macri and Looper (2003: 139) describe the head-shaped logograph T1006a that as an image of “maize personified” with a mirror on its forehead. Schele (1988: 303) even argues that the mirror was so closely related to K’awil that the mirror element infixed in the god’s forehead, as in signs such as T1030de and other “smoking mirror” glyphs (Macri and Looper, 2003: 171-172), served as a “semantic determinative” that referred to the god. Mirrors also appear within phonetic head variants thought to depict other divinities, including T1017 (Macri and Looper, 2003: 173) and T1030o (Montgomery, 2002: 120).

Most of the anthropomorphic hieroglyphs containing mirror elements appear to carry overt cosmological connotations evident in their graphic and/or linguistic features. However, mirror-like symbols also occur in anthropomorphic hieroglyphs with no obvious religious associations, at least not any currently understood by modern epigraphers. A T24-like element appears on an unusual animal-like head variant of T672 JOM (Montgomery, 2002: 119), whose use in the title ch’ahoom may be yet another visual allusion to the mirror’s ritual connotations (Montgomery, 2002: 73). Other anthropomorphic hieroglyphs with an internal mirror glyph-like component include T738c u, thought to illustrate a fish or a shark; ACH KÀAN/CHAN that may represent a snake; the skull-like AM1 AJAW/NIK; and the bird-shaped T746; (Macri and Looper, 2003: 53, 59, 66, 152-153). The placement of T24-, T121-, or T617-like elements within these anthropomorphic logograms corresponds to the aforementioned archaeological and other icono-graphic evidence for individuals wearing mirrors during participation in ritual events. The hieroglyphic association of mirrors with deities also strengthens the argument for the mirror’s role as a religious symbol among the ancient Maya.

The arrangement of the mirror components in the glyph PM6, a head variant of the number “11” (Macri and Looper, 2003: 145), is probably the most anomalous in form of the head-shaped hieroglyphs associated with mirrors. The two mirror elements are stacked upon each other where one would expect to see the figure’s mouth. In spite of the lack of archaeological and iconographic evidence for the placement of mirrors in ancient Maya mouths, a clue to the meaning of this image may be found in other hieroglyphs. According to the analysis of Macri and Looper (2003: 176, 274), the logogram and numerical classifier ST4 and the phonetic hieroglyph 1M3 depict a mirror inside of a mouth. Furthermore, the placement of the mirrors in ST4 and 1M3 is reminiscent of that in ZVG, a hieroglyph that, according to Macri and Looper (2003: 248), both illustrates and signifies a canoe (e.g. Kerr, n.d.: 4692). Although the underlying elements of 1M3, ST4, and ZVG resemble iconographic depictions of canoes (e.g. Stone and Zender, 2011: Figure 50.1-4), the elements that emerge from them seem to indicate an underlying link to ancient Maya mirror symbolism. Unlike other hieroglyphs thought to signify canoes that contain rectangular, apparently inanimate elements (e.g.Fitzsimmons, 2009: Fig. 19; Macri and Looper, 2003: 248; also see Tate, 1992: Figure 28), all three of these hieroglyphs feature a mirror or a face peering out from a depression tilted up and to the left at a slight angle.

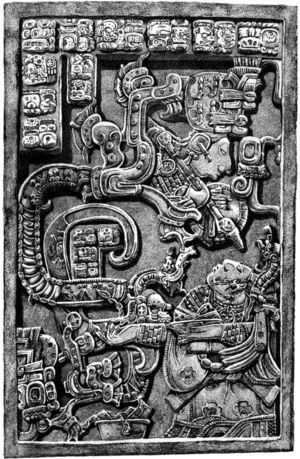

As discussed previously, ancient Maya use of mirrors in bowls is documented archaeologically and is often associated with ritual, particularly with shamanism. The placement of the mirrors in ST4, 1M3, and ZVG is analogous to that of mirrors in iconographic depictions of mirrors in bowls, which are often angled upwards towards the viewer (e.g. Kerr, n.d.: 559, 625). Ancient Maya iconography also contains images of serpents and other anthropomorphic figures emerging from mirrors (Taube, 1992a: 195–197, Figure 21e) or bowl-like receptacles, like that cradled by Lady Xook on Yaxchilán Lintel 25 (figure 6). In some instances, another figure holds up such a container as if to ceremonially offer up its contents (Stone and Zender, 2011: Figures 63.1, 64.2, 71.2). Besides reinforcing the ritual connotations of these objects, such images also suggest that the ancient Maya believed that mirrors, like caves, allowed the movement of supernatural beings into the human world (Taube, 1992a: 193-195).

I suggest that these hieroglyphs actually symbolize the use of mirrors within bowls as reflectors, illustrating either the mirror itself or the reflection of the viewer that would appear within the bowl or mouth substitute. The canoe connotations of ZVG could thus be indicative of the aforementioned link between liquid and mirrors as reflective surfaces used in ceremonial contexts. These hieroglyphs that depict mirrors in bowls may also illustrate the symbolic relationship between mouths and caves, with both functioning as orifices through which elements are able to cross into different states of being. Maya iconography contains numerous illustrations of anthropomorphic mouths functioning as caves (Markman and Markman, 1989: 16; Stone, 1995: 23), or at least as portals from which figures emerge, as on Yaxchilán Lintel 25 (figure 6); it would not be surprising, given its symbolic role as an arbiter between the supernatural and the human, if the mirror were also a member of this cultural complex.

Evidence for the symbolic function of mirrors among the ancient Maya may also be approximated through semantic analysis of the mirror hieroglyphs and their associated compounds. T24 li commonly functions as the postfix il to denote inherent possession or abstraction (Lacadena and Wichmann, n.d.: 37). This grammatical use could be related to a mirror’s reproduction of a true-to-life, albeit distorted, reflection: mirrors neither add additional elements not already present, nor remove any that are already part of the scene. The optical property of mirrors may be represented in the homophony of T24 li/il and the logogram T618v IL “to see” (Montgomery, 2002: 96-97), a correspondence also noted by Healy and Blainey (2011: 235). In addition, the key role of T617a in “accession” verb phrases on texts from the Group of the Cross at Palenque as discussed by Schele and Miller (1983: 3-9) corroborates the aforementioned indications that mirrors were often associated with the elite and functioned in rituals such as exchanges of political power.

Outside of traditional epigraphic contexts, mirror glyph-like elements also occur with notable frequency in iconography, often in contexts in which they appear to represent artifactual mirrors or indicate shininess more generally. The relationship between writing and imagery in Mesoamerica is being increasingly questioned as researchers are recognizing the strong degree of overlap and co-influence between what scholars traditionally identified as two separate media of cultural expression (e.g. Boone and Mignolo, 1994; Boone and Urton, 2011; Stone and Zender, 2011). As such, I have chosen to refer to the elements discussed in the following paragraphs that appear in “iconographic” contexts, that is, outside of sequenced blocks of hieroglyphic that form a “text,” as “glyph-like”. This attempt to reconcile the similarities between these elements and the mirror hieroglyphs with sometimes different, sometimes similar contexts in which they appear is admittedly insufficient. However, the discussion of the relationship between writing and iconography is not directly relevant to the problem at hand, for which reason I will therefore lay it aside for the time being.

Occasionally, the elements resembling T24, T617, or T121 are depicted as isolated objects, as on a painted ceramic vessel that shows several T121-like figures propped up at an angle facing to the left as if to facilitate viewing by an anthropomorphic character (see Robicsek and Hale, 1981: Vessel 86). Most often, however, mirrors are illustrated in direct association with an anthropomorphic figure. For instance, many stelae and lintels from across the ancient Maya region depict figures who are wearing or are otherwise associated with two or more mirror glyph-like elements (e.g.Schele and Miller, 1983: Figures 4a-j; Milbrath, 1999: 238, Figure 6.3o; Grube and Gaida, 2006: Abbildung III.7 and III.8). These characters are thought to be cosmologically significant. Mayer (1980: 59), for example, comments that the bench upon which God K is sitting on the unprovenienced capstone features several “glyphic elements,” including an image of T24.

The cosmological symbolism of individuals associated with mirrors is also apparent in illustration of mirror glyph-like figures with other ancient Maya deities and anthropomorphic beings that were intimately associated with celestial phenomena. For instance, Postclassic Maya iconography occasionally features images of mirrors on the anthropomorphic figure of the rain deity Chac (e.g.Grube and Gaida, 2006: Abbildung III.6), perhaps to reference glistening raindrops (Milbrath, 1999: 202). Indigenous tales described the sun as a heavenly mirror whose shininess was also symbolized by mirror glyph-like figures depicted on other solar deities, like Gods III and C (Carlson, 1981: 128; Milbrath, 1999: 92, 102, 226). Milbrath (1999: 88-89) argues accordingly that images of a T167a-like figure on the Sun God’s forehead denote an ancient Maya connection between mirrors and the sun. In certain contexts, such as on some iconographic snakes thought to depict the Milky Way, mirror glyph-like figures may represent stars (Milbrath, 1999: 198, 283). Mirrors also appear in association with some lunar deities, possibly in allusion to shining quality of the moon (Milbrath, 1999: 133, Fig. 410).

Mirrors in spoken languageLinguistic evidence from spoken Maya contexts also includes important clues to the symbolic significance of mirrors among the ancient Maya. Among the modern Maya, there are two principal words for mirror: nen, the Western and Central term with which the mirror hieroglyphs are most commonly associated, and lem, from the Eastern Maya languages (Schele and Miller, 1983: 12). Historical linguists reconstruct *lem as the original proto-Maya form (Kaufman, 2003: 471-472; Schele and Miller, 1983: 14). Although the Western and Central Maya term for “mirror” appears to have shifted from lem to nen over time, lem did not disappear completely from the Western and Central vocabularies. Instead, the word underwent semantic widening and was retained as a more general reference to shininess and reflective surfaces or substances (Schele and Miller, 1983: 14).

Not unexpectedly, both nen and lem have been incorporated into certain words and phrases denoting specific objects, substances, or phenomena characterized by shininess. These can range from the man-made, including liquor, glass, and eyeglasses (Schele and Miller, 1983: 13), to the natural, such as lightning (Kaufman, 2003: 472; Schele and Miller, 1983: 13) and the reflective surface of water, which is compared to a mirror in the Motul phrase nen ba, meaning “to look at oneself in a mirror or in the water” (Bolles, 2001: 3942). Nen is often found in various Maya languages as the root of verbs such as “to shine” or “to reflect” (Kaufman, 2003: 472; Schele and Miller, 1983: 13-14).

Interestingly, the same syllable il with which hieroglyph T24 is usually transcribed when functioning as a grammatical suffix denoting inherent possession or abstraction, is also found as a root in various verbs for “to look” or “to see” in some Maya languages (see Bolles, 2001: 2618-2619; Kaufman, 2003: 204-206, 471; Schele and Miller, 1983: 13). Like nen, this root is also present a handful in Maya verbs denoting the action of “reflecting” (see Kaufman, 2003: 205). Unlike lem and nen, il does not seem to have functioned as an independent word for “mirror”. Nonetheless, the close semantic relationship of these two roots in both modern and historically reconstructed Maya languages provides further evidence of the connotations linking the mirror hieroglyphs T24, T121, and T617 to each other and to their manifestations in less explicitly hieroglyphic contexts.

The linguistic data also reveals an association of mirrors with the human, both as a physical body and as a personality that is shared across many, if not all modern Maya linguistic groups. In modern Tzotzil, the term denoting the pupil of the eye, nen sat, is a compound formed from the terms for “mirror” and “face” (Taube, 1992a: 181). Another compound meaning pupil, nenil ich, is composed of nen “mirror,” the grammatical suffix il denoting possession, and ich “eye” or “face” (Bolles, 2001: 3946, 2581; Bricker, Po’ot Yah, and Dzul de Po’ot, 1998: 11). In addition, nen and il function as roots in Mopan and Q’eqchi’, respectively, in terms that denote the “face” (Kaufman, 2003: 206, 471). The apparent semantic connection between mirrors and faces may point to certain Maya cultural values surrounding the human face, such as its partial function as a reflection of the individual’s internal reactions to external stimuli. This modern linguistic evidence supports the previous assertion that the ancient Maya associated mirrors with the face, including the eyes and the forehead.

Both the human and the mirror respond to their external environment with a reaction that, while in part standardized by experiences and characteristics shared with fellow beings, is nonetheless distorted by personal factors. Linguistic research also suggests that mirrors are associated in Maya culture with certain human faculties, especially those related to contemplation. Various Maya languages contain the roots il, nen, or lem in words referring to the actions of “contemplating,” “thinking,” or “knowing” (see Bolles, 2001: 3942; Kaufman, 2003: 205-206; Schele and Miller, 1983: 13). Other post-Conquest Maya terms, such as nenil ol “imagination” (Bolles, 2001: 3946), may provide additional evidence of a Maya belief in the function of one’s creative or intellectual faculties as a reflection of the human ol “heart”, “will,” or “condition” (Bolles, 2001: 4208).

Furthermore, Taube (1992b: 34) notes that the itz in the Maya name Itzam may actually be a loan from Nahuatl that was tied to the belief system surrounding mirrors that was shared between the Maya region and Teotihuacan. Both the Nahuatl root itz and the Maya itz communicate the idea of predicting or contemplating. The Nahuatl term furthermore refers to obsidian, and in Yucatec Maya, itz denotes certain liquids, including dew and human tears. These meanings may allude to the ancient use of obsidian and liquid mirrors in divinatory scrying (Taube, 1992b: 34).

Maya terms associated with mirrors and shininess also appear in words and phrases denoting specific social functions, most significantly political and/or religious leadership roles. The same root il that appears in verbs related to observation also functions as an initial syllable in some Maya words for “healers” (Kaufman, 2003: 206). This use is possibly a reference not only to the belief in these individuals’ supernatural ties that allowed them to identify and counteract human maladies that others are unable to detect, but also to the ritual practice of scrying, previously discussed in the context of ancient Maya shamanism. In addition, conquest-era documentation of Yucatec speakers includes phrases in which the Maya denoted priests and rulers as the u nen cab, or the “‘mirror of the community’” (Coe, 1988: 227), evidence which Schele and Miller (1983: 14) interpret as indicating the use of the mirror glyphs in accession texts. Saunders (1988: 20) argues that this linguistic evidence, combined with archaeological and iconographic data relating mirrors with jaguars and rulership, indicates that the ancient Maya believed that political and religious leaders could “see and control people with their mirrors.” However, it seems more probable that mirrors were a metaphor for, rather than a tool directly used in population control, as Carlson (1993: 248) suggests. The connection to the supernatural world of the gods and ancestors that the mirror represented, rather than the mirror itself as a physical object, allowed the rulers to assert their authority over the rest of the population.

Mirrors and cognitionStudies of the effect of mirror-image reversals on mental processing have explored both the cultural differences in the significance attributed to mirror images in written contexts and the impact that writing systems have on individuals’ perception of image reversals (see Danziger and Pederson, 1998; Kolinsky et al., 2011). Danziger and Pederson (1998), for example, studied the acceptance or rejection of mirror images among both literate and non-literate native speakers from a wide variety of linguistic and cultural backgrounds. They found that the tendency to distinguish between two-dimensional right/left mirror images is not inherent, but rather a learned reflex influenced at least in part by cultural factors, including literacy.

Of their subjects who natively spoke the Maya languages Tzeltal, Mopan, or Yucatec, the non-literate participants were much more likely than their literate counterparts to accept the mirror images as being part of another, non-mirror image figure. Furthermore, the difference between the rate of acceptance among non-literate versus literate speakers was higher among these Maya groups than among other language populations (see Danziger and Pederson, 1998: Figure 2). This trend suggests that cultural values or experiences shared among these speakers may be altered by the processes through which they acquire literacy, which, as Danziger and Pederson note (1998: 159), is usually achieved in Spanish, not in their indigenous tongue.

Furthermore, the nature of the script in which one is literate may influence one’s tendency to distinguish between left/right mirror images. As Danziger and Pederson point out (1998: 162), the participants literate in a Roman script, including the Maya speakers, have presumably been trained to distinguish between certain letters that are mirror images of each other and yet represent distinct phonemes, like “p” and “q”. The authors note the relatively high rate of mirror image acceptance among Tamil speakers, suggesting that these individuals’ use of a non-Roman script that does not distinguish between left/right mirror images is at least partially responsible for their tendency to accept left/right mirror images as equivalent to the original forms. However, Danziger and Pederson’s (1998) Maya speakers also demonstrated an unusually high acceptance rate of mirror-image forms, second only to the Tamil speakers and first among all participants who natively spoke a language written in Roman script, regardless of whether or not they were literate. This trend seems to contradict the authors’ hypothesis that one’s literacy training in a Roman script would cultivate one’s impulse to differentiate between mirror images.

These results are corroborated by a later study of mirror-image discrimination using three-dimensional objects. Danziger (2011) found that native Mopan speakers, both literate and illiterate, were significantly more likely than American native English speakers to describe mirror-image three-dimensional forms as “not different”. Unlike the American participants, the native Mopan speakers tended to adopt what Danziger (2011: 854) describes as an intrinsic frame of reference, or one in which the anchor is the ground, rather than a point in space identified by cardinal direction of left/right orientation. Indeed, Danziger (personal communication, 2012) believes that mirror image perception is not a development stage undergone by all children. Instead, comparison of data from literate and non-literate speakers of languages recorded in both Roman and non-Roman alphabets indicates that tendency to identify mirror images as significantly different is learned, perhaps as a result of training in writing systems in which distinctions between mirror-image forms is critical to conveying meaning (Danziger, personal communication, 2012). These data suggest that the modern Maya may share tendency to accept such reversed forms as equivalent to the originals in certain contexts. Such a trend, if inherited from their ancestors, could explain the preponderance of vertical symmetrical hieroglyphs in the ancient corpus and would also suggest that the ancient mirror-image texts may have communicated symbolic connotations without necessarily altering their linguistic message.

In a separate study, Le Guen (2011) examined the frames of reference of Yucatec Maya speakers and discovered that although Yucatec men and women exhibited lexical differences in their spoken references to space, both groups expressed a geocentric spatial orientation in their co-speech gestures. In a geocentric, as opposed to an intrinsic or an egocentric, frame of reference, the spatial relationship between objects is expressed in terms of the external surroundings, most significantly the cardinal directions (Le Guen, 2011: 908). As Le Guen (2011: 928-929) concludes, “gesture is part of the semiotic system” and constitutes “a communicative medium through which culture-specific patterns of thought can be transmitted”. Similarly, the reversed orientation of the glyphs in the mirror-image monumental texts probably conveyed certain cultural values that either reinforced a message already expressed elsewhere on the monument, or added a conceptual element that furthered the viewer’s understanding of the monument as a whole.

Discussion and conclusionThe evidence compiled in the preceding sections suggests that the mirror-image structure of these monuments was a form of visual metaphor that both contributed to reinforced the message of the monument as a whole. Of the many symbolic meanings that the structure of mirror-image monumental inscriptions may have conveyed, the connection between mirrors and political and religious power seems particularly salient. As mentioned, evidence for the ancient Maya use of mirrors in shamanistic contexts indicates that mirrors communicated a religious authority that, in certain contexts, may have played a significant role in establishing political legitimacy. As objects, mirrors were “symbols of ritual upon which identity and legitimacy depended” and “therefore symbols of rule” (Saunders, 1988: 22) that constituted important tools in negotiating political power, especially in ceremonial contexts.

Most of the mirror-image monumental inscriptions examined in this study record ceremonies, many of which were associated with political events and particularly with accession rites, include sacrifice. The panels, bench, and Reviewing Stand from Temple 11 at Copán, as well as Yaxchilán Lintel 25, record rituals connected with accession; Site R Lintel 3 memorializes a vassal’s expression of loyalty to his ruler; and the Kimbell Lintel documents the ceremonial presentation and preparation of captives. All of these events would have asserted and affirmed the ruling protagonists’ political legitimacy and supremacy. Carlson (1981: 128) also posits that mirrors played a physical and symbolic role in a “‘mirror ceremony’” that served to mark “the transfer of royal lineal power, heir designation, or accession to rulership”. Documenting political successes on monuments using mirror-image inscriptions may have been a double-dip in the bowl of political symbolism: not only could rulers thus evoke the legitimacy generally associated with monumental texts (see Herring, 1998: 114; Hull, 2003: 372-374), but they were also able to explicitly connect themselves with the authority and power that the mirror itself represented.

The concept of the mirror as a portal between the supernatural and human worlds may have been especially influential in determining the political significance of mirrors in ancient Maya society. Ancient Maya political and religious authority figures may have used mirrors to contact members of the divine realm, which would have positioned them as mediators between the laypeople and supernatural beings (Healy and Blainey, 2011: 240). The impurity of the mirror’s distorted reflection would have heightened the illusion that it created another world to which it allowed the user temporary access (Saunders, 1988: 1, 7, 21). By establishing this connection, however tenuous, to the supernatural sphere, the human user would have experienced a certain change of state induced by this ritual exposure to the otherworldly realm.

Sanchez (2005: 262-264) suggests that certain architectural structures were imbued with visual references to ancient Maya cosmology and the otherworldly, so that participants were metaphorically transported to the supernatural realm upon entering such an architectural space. However, I extend this capacity for ritual transformation to the monuments represented in this study, many of which were elements of larger architectural structures. I propose that mirror-image monumental inscriptions were visual metaphors for the ritual transformation of the monument’s protagonists and, perhaps more significantly, of the monument’s ancient Maya viewer. Mirror-image monumental texts would have reminded the viewer of the cosmological significance of possessing and using a mirror and thus of the authority of those responsible for the monument’s creation. By reversing the hieroglyphs and thus presuming to present an inverted, ceremonial interpretation of reality, mirrored hieroglyphic passages furthermore extended ritual participation beyond the monument’s protagonists to the viewer, actively engaging the viewer in the ritual process by connecting the viewer with the supernatural. Reversed monumental texts thus not only passively symbolized, but also actively facilitated the viewer’s transformation into a ritual participant whose access to the otherworldly made the viewer something more than a mere human. The mirror image was not intended to be a perfect replica of reality, but rather a window into an alternative world.

In the case of Yaxchilán Lintel 25 (Figure 6), for instance, an anthropomorphic figure is depicted emerging from the mouth of a serpent. Given the aforementioned symbolic relationship between caves, mouths, and serpents, this image likely indicates that the protagonist is emerging from a supernatural realm. Scholars often interpret the scene on Lintel 25 as illustrating the function of ritual blood-letting in allowing the ruler or even his wife “to transcend the world of the mundane and communicate with gods and divine ancestors” (Schele and Miller, 1986: 177; Steiger, 2010: 5). Yet it was the monument’s living viewer, not the actors described on the monument, who interacted directly with the one component of the physical lintel most directly related to a mirror: the reversed text. Much as the serpent’s mouth symbolizes a passageway for the anthropomorphic figure on the monument, the mirror-image inscription acts as a metaphorical channel that draws the viewer into the ritual complex recorded on the lintel, facilitating the viewer’s own transformation. The mirrored text thus encourages the viewer to participate in the ceremony and to come into contact with the supernatural, much as the monument’s protagonists do by taking part in the rituals.

The role of mirror-image inscriptions in facilitating the viewer’s ritual participation and change of state may have been especially important on monuments recording political milestones, particularly accession rituals. In these cases, the symbolism of the reversed text indicating transformation may not have been limited to representing the viewer’s general change of state into a ritual participant. The mirror-image structure may have also alluded to broader political and social changes represented by the new ruler’s assumption of power and the transformations that the individual subject would have undergone as a result. This symbolic connection is evident in the speech of the Conquest-period Maya who described their religious and political rulers as u nen cab or u nen cah, a mirror reflecting the earth or the people (Carlson, 1981: 127). The ancient Maya may have conceived of changes in political leadership as indicative of transformation on the level of both society and the individual civilian. As a result, the use of mirrored hieroglyphs on monuments recording politically significant events would have been an even more salient indication of the events’ consequences.

Furthermore, the contrast between unreversed and reversed passages was essential in communicating the transformations occurring in both the broader Maya political landscape and the individual viewer. The hieroglyphic texts on Yaxchilán Lintel 25 (figure 6), Site R Lintel 3 (see Mayer, 1995: Plate 258), the Kimbell Lintel (see Mayer, 1980: Plate 37), the Mayer capstone (see Mayer, 1980: Plate 68), Uaxactún Stelae 6 and 20 (see Graham, 1986: 147-149, 181-185), the Copán Temple 11 bench and panels (see Schele, 2000; Schele, Stuart and Grube, 1989), and the Reviewing Stand from Copán (see Schele, 1987: Figure 1) all juxtapose mirrored and un-mirrored passages. Even the poorly preserved doorway column identified by Mayer (1995: 54-55) displays of two columns of oppositely-oriented glyphs (see Mayer, 1995: Plates 206 and 207). Of the monuments with mirror-image texts that were used in this study, only the Copán fragments display no left-to-right hieroglyphs (see Schele and Grube, 1991: Figure 2), but too little of the text has been preserved to permit their inclusion in the analysis of these monumental inscriptions. The structural differences between the various sections may also have highlighted their disparities in content. On Yaxchilán Lintel 25 (Figure 6), for instance, the mirrored text on the underside focuses on the conjuring rituals associated with Itzamnaaj Bahlam III’s accession, whereas the traditionally oriented inscription on the front edge discusses what seems to be the dedication of the lintel itself, which occurred after the accession. The unreversed conclusion of Site R Lintel 3 consists primarily of Yaxhun Bahlam IV’s titles; the contrast presented with his reversed name glyphs at the conclusion of the mirrored passage may indicate the transformational consequences of his reign upon the polity and its population.

More importantly, perhaps, the direct juxtaposition of different reading orders in order to convey meaning may also have been a response to the cognitive tendency of humans to unconsciously reinterpret mirrored letters and words as unreversed, even among individuals with literacy training that would presumably suppress this ability (Duñabeitia, Molinaro and Carreiras, 2010: 3007). The direct co-occurrence of left-to-right and right-to-left oriented hieroglyphic texts on the same monument would have drawn attention to the differences between them and thus to their metaphorical representation of the viewer’s change of state, thereby heightening the monument’s transformative effect upon the viewer. This effect would have been particularly important in facilitating recognition of the unusual structure by an illiterate viewer who was relatively unfamiliar with the glyphs. Just as the relationship of the glyphs to each other was more significant in conveying meaning than the orientation of each individual glyph, it was the structural contrast between the differently oriented passages, rather than the unusual representation of each glyph, that most effectively communicated the change in state that the monument both represented and effected in the viewer.

The hieroglyphs, the images, and their content together became part of the viewer’s ritual experience, channels through which the viewer achieved contact with the supernatural realm. Mirroring a passage of monumental text thus affected the viewer’s relationship with the monument as a whole. The contrast in orientation created by juxtaposing glyphs written in opposite directions signaled to the viewer the change of state associated with the activities and protagonists recorded on the monument. Furthermore, the mirror-image orientation actively altered the viewer’s environment by presenting a reflection of a reality different from that known to the viewer. The alternative structure encouraged the viewer to reevaluate reality and relocated him or her to an alternative, ritual context. The mirrored directionality of the hieroglyphic text directly engaged the viewer, transforming the context in which the viewer would have interpreted the monument’s message and thereby shaping the viewer’s relationship with the monument.

First and foremost, I would like to thank John Henderson for his support throughout this project. In addition, I am indebted to Kathryn M. Hudson for opening my eyes and for sharing her passion and knowledge with me. Many thanks also to Fred Gleach, for graciously offering feedback on this work; to Eve Danziger, for the thought-provoking discussion; and to two anonymous readers, for their comments during the review process. Any factual and analytical errors that persist in this work are mine alone.

Nota del editor: El autor deber referirse al Códice de París, pp.: 22-24, y al Monumento I de La Mojarra.

In order to streamline my discussion, I will refrain from offering a detailed epigraphic, archaeo-logical, and iconographic analysis of the individual monuments here. The reader is instead referred to the following publications for detailed studies and images of each of the eleven mirror-image monuments: Robinson, 2010; Schele and Miller, 1986; Steiger, 2010 (Yaxchilán Lintel 25); Palka, 2002; Schele, 1991b and 1991c; Schele and Freidel, 1990 (Site R Lintel 3); Mayer, 1980; Schele and Miller, 1986 (Kimbell Lintel); Mayer, 1980; Schele and Miller, 1986; Danien, 2002; Jones, 1975 (Mayer Capstone); Houston, 1998; Mayer, 1995 (Chilib Fragment); Schele and Freidel, 1990; Schele, Stuart, and Grube, 1989 (Copán Temple 11 panels); Palka, 2002; Schele and Miller, 1986; Viel, 1999 (Copán Temple 11 bench); Baudez, 1994; Schele, 1987 (Copán Reviewing Stand); Schele and Grube, 1991 (Copán Fragments); Graham, 1986 (Uaxactún Stela 6); Coggins, 1980; Graham, 1986 (Uaxactún Stela 20, lado izquierdo).

For an overview of the ancient Maya hieroglyphs, the reader is referred to Kettunen and Helmke, 2011.

I employ the orthographic guidelines given in the 2011 XVI European Maya Conference Handbook Introduction to Maya Hieroglyphs for all transliteration and transcription of the hieroglyphic texts. Transliterations are in bold, with logographic readings in UPPER CASE and syllabic readings in lower case. Reconstructed sounds are not included in transliterations. Transcriptions are italicized. For more details and examples, please consult the Conference Handbook (Kettunen and Helmke, 2011: 14-15). References to specific hieroglyphs will identify them according to their Thompson (T-) numbers whenever possible. Glyphs with no T-number will be referenced using the tripartite, alphanumeric designations used in volumes I and II of The New Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs (see Macri and Looper, 2003; Macri and Vail, 2009).

The orientation of its grammatical subfix wa (T130) is not indicative of the orientation of this glyph block as a whole within the text, given the variation possible in the arrangement of the two components of T130 even within the same inscription (e.g. Yaxchilán Lintel 10, glyph blocks B3 and F3, in Graham and von Euw, 1977: 31).