Differences in patients and nurses’ perceptions of caring behaviors arouse patient dissatisfaction. Continuous monitoring and assessment of caring behaviors has revealed its problems, and this in turn would promote care services by planning rational interventions and removing the problems. The present study aimed to compare nurses and elderly patients’ perceptions of nurses’ caring behaviors in intensive care units in accordance with Watson's transpersonal caring theory.

MethodsIn this descriptive-analytical study, 70 nurses were selected using the census method, and 70 elderly patients over 60 years old were also selected using purposive sampling method from the intensive care units of Lorestan University of Medical Sciences during 2012–2013. Caring Behavior Inventory for Elders (CBI-E) was adopted in this research to detect the nurses and elderly patients’ perceptions of caring behaviors. In the data analysis phase, Kruskal–Wallis, Mann–Whitney U, and Pearson correlation tests were used.

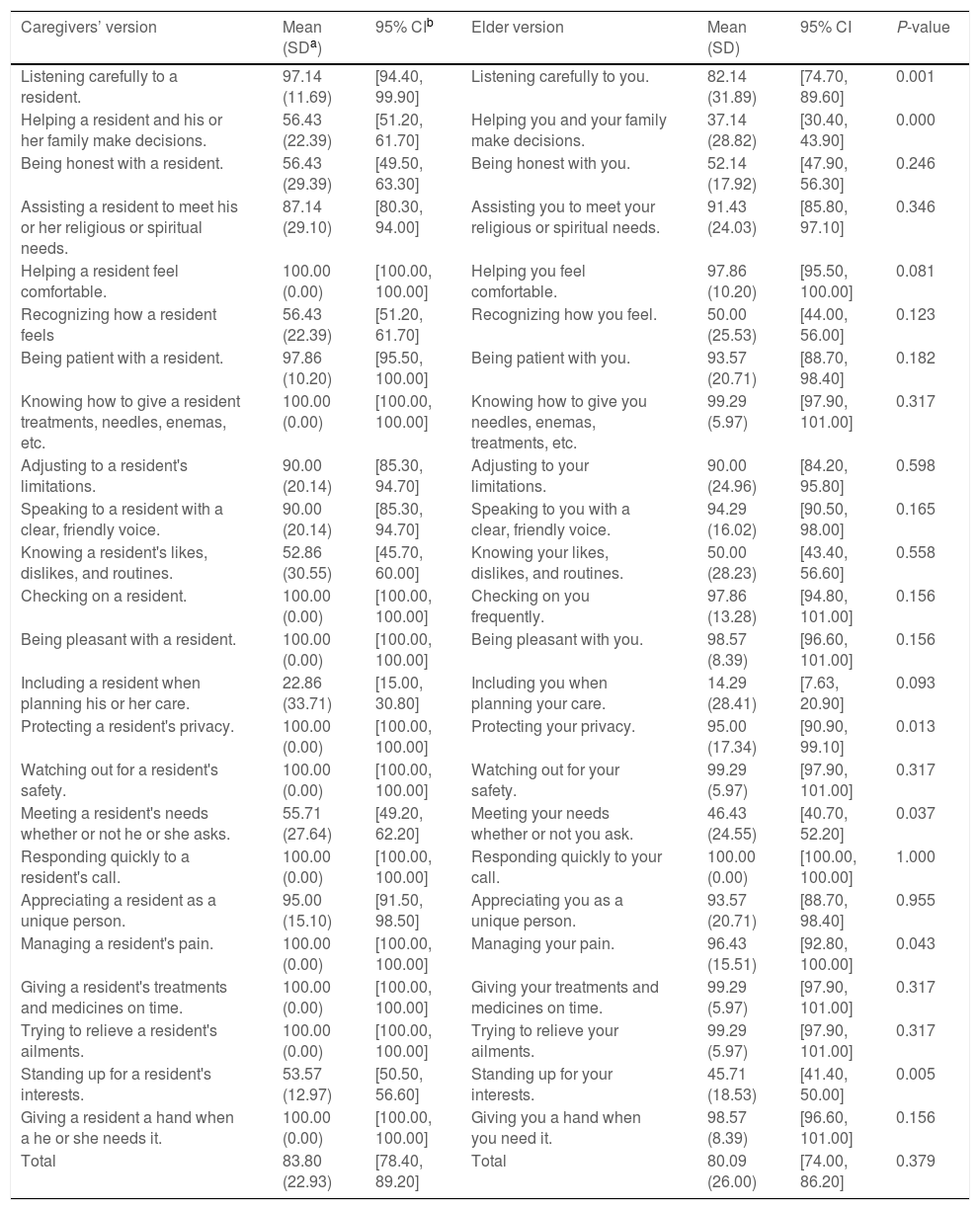

ResultsThe research findings revealed no statistically significant difference between the total scores of nurses’ 83.80 (22.93), 95% CI [78.40, 89.20] and elderly patients’ 80.09 (26.00), 95% CI [74, 86.20] perception of nurses’ caring behaviors (P=0.379). From the viewpoint of the nurses and elderly patients, responding quickly to a patient's call 100.00 (0.00), 95% CI [100.00, 100.00] had the highest mean scores and patient participation in caring process had the lowest mean scores among nurses 22.86 (33.71), 95% CI [15.00, 30.80] and elderly patients 14.29 (28.41), 95% CI [7.63, 20.90].

ConclusionThis study indicated the elderlies and nurses’ similar perceptions of caring behaviors in intensive care units. This finding would help nurses to recognize and prioritize the elderly patients’ care needs, thereby promoting the quality of care services.

Las diferencias en las percepciones de los pacientes y las enfermeras sobre las conductas de cuidado despiertan la insatisfacción de los pacientes. El seguimiento y la evaluación continuos de las conductas de cuidado han puesto de manifiesto sus problemas, lo que a su vez promovería los servicios de cuidado mediante la planificación de intervenciones racionales y la eliminación de los problemas. El presente estudio tenía como objetivo comparar las percepciones de las enfermeras y de los pacientes ancianos sobre las conductas de cuidado de las enfermeras en las Unidades de Cuidados Intensivos de acuerdo con la teoría de Watson's Transpersonal Caring.

MétodosEn este estudio descriptivo-analítico, se seleccionó a 70 enfermeras mediante el método de censo, y 70 pacientes ancianos mayores de 60 años mediante el método de muestreo intencional de las Unidades de Cuidados Intensivos de la Lorestan University of Medical Sciences durante 2012-2013. En esta investigación se adoptó el Caring Behavior Inventory for Elders (CBI-E) para detectar las percepciones de las enfermeras y de los pacientes ancianos sobre las conductas de cuidado. En la fase de análisis de datos, se utilizaron las pruebas de Kruskal-Wallis, U de Mann-Whitney y la correlación de Pearson.

ResultadosLos resultados de la investigación no revelaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre las puntuaciones totales de las enfermeras, 83,80 (22,93), IC del 95%: 78,40-89,20, y las de los pacientes ancianos, 80,09 (26,00), IC del 95%: 74 - 86,20, de percepción de las conductas de cuidado de las enfermeras (p=0,379).

Desde el punto de vista de las enfermeras y de los pacientes de edad avanzada, la respuesta rápida a la llamada de un paciente (100,00 [0,00], IC del 95%: 100,00-100,00) tuvo las puntuaciones medias más altas y la participación del paciente en el proceso de cuidados tuvo las puntuaciones medias más bajas entre las enfermeras (22,86 [33,71], IC del 95%: 15,00-30,80) y los pacientes de edad avanzada (14,29 [28,41], IC del 95%: 7,63-20,90).

ConclusiónEste estudio indica que los ancianos y las enfermeras tienen una percepción similar de las conductas de cuidado en las unidades de cuidados intensivos. Este hallazgo ayudaría a las enfermeras a reconocer y priorizar las necesidades de atención de los pacientes ancianos, promoviendo así la calidad de los servicios de atención.

According to some evidence, patients and nurses have different perceptions of caring behaviors, thereby reducing the quality of care. Some studies have revealed that caring behaviors reflecting humanity and altruism are of great importance to patients.

What it contributes?Knowing patients’perceptions of caring behaviors and comparing them with nurses’ perceptions in statement synthesis to build nursing theories in this specific area can be helpful. This research is based on theory and its results can be added to nursing knowledge and science and used in practice.

Implications of the studyAccording to the study findings, nurses’ and elderly patients’ perceptions of caring behaviors are somehow similar, thereby helping nurses to correctly prioritize their patients’ care needs and provide optimal care, which leads to patient satisfaction.

Caring as a moral ideal and a main task in nursing is a key component distinguishing the roles of nurses and physicians.1,2 The importance of nurse–patient interactions based on caring behaviors has been proven in philosophical discussions, theories, and innovative research by the renowned theoreticians Watson, Leininger, Boykin, and Swanson.3 According to Watson, continuous monitoring and assessment of caring behaviors reveals its problems. In this regard, rational interventions and troubleshooting would improve caring and determine its dimensions. This would also add new dimensions and angles to nursing education and research programs.4

Caring behaviors are of great important for all help-seekers; however, they are more highlighted for the elders due to their special condition.2,5 The number of people 60 years or older in the world is increasing (World Health Organization, 2018), rising from 900 million (12% of the world population) in 2015 to 2 billion (22%) in 2050.6 In Iran, it is also estimated that this group of population account for 19.70% of the total population by 2050,7,8 highlighting the need for caring resources, especially caring in intensive care units. Vulnerability is one of features observed in each human being, especially the elderly patients 9 as they usually possess low physiological reserves and suffer from several comorbidities with complicated diagnoses.10,11 Some barriers to taking care of the elderly are lack of adequate expertise and education, insufficient knowledge and negative attitudes toward the elderly, anxiety, and lack of self-confidence.12,13 Some evidence also suggests the lack of quality care services for the elderly, compared to other patients, which would enhance recovery time, hospitalization time, the frequency of mental and physical disorders, and mortality rates and decrease the efficiency of intensive care units.14,15 Moreover, intensive care units are potentially harmful places for the elderly patients, highlighting such patients’ need for further attention.16

The intensive care units nurses play a critical role in providing comprehensive direct individual care to meet their patients’ mental, physical, and social needs2; however, their perceptions of caring behaviors should be detected to facilitate necessary patient care in intensive care units.17 There are several challenges to taking comprehensive care of the elderly, some of which are as; communication barriers such as visual, auditory, and cognitive changes. Such challenges and barriers poses double stress on nurses and reduces their concentration on communication and caring behaviors as such the elderly patients are marginalized.11 A variety of other factors may also affect nurses’ caring behaviors: patient diagnosis, work environment and conditions, nurses’ age and experience, and personal beliefs.2

According to some evidence, patients and nurses have different perceptions of caring behaviors, thereby reducing the quality of care and patient satisfaction. Some studies have revealed that caring behaviors reflecting humanity and altruism are of great important to patients; however, nurses are concerned with timely implementation of treatment instructions and potentials to offer care services.18–20 Accordingly, the comparative measurement of nurses’ caring behaviors from the perspective of both patients and nurses provides better feedback for nurses and nursing managers.1 There have been a large number of studies focusing on different perceptions of caring behaviors, some of which have compared caring behavior perceived by nurses, patients and nursing students,21 elderly patient's perceptions of caring behavior,11,22 and perceptions of caring behaviors in intensive care units.2,17 To the best knowledge of the researchers, no study, however, has compared nurses and elderly patients’ perceptions of caring behaviors in intensive care units. Given the need to focus on patient-centered care, the measurement of caring behaviors is of important11; therefore, the present study aimed to compare the nurses and patients’ perceptions of caring behaviors in intensive care units and to detect different dimensions of these behaviors.

The theorist Jean Watson attributed a new meaning to care practice, advocating an approach that would allow her to go beyond scientific knowledge and consider humanistic aspects to meet the needs of the patient, family and community. Therefore, the Theory of Transpersonal Caring is defined as a framework that contemplates care in different scenarios and with greater interaction between the health professional and the patient. Nursing should not be based on the traditional biomedical model, which focuses only on curing diseases through a series of established protocols.23 The original work was organized around 10 carative factors as a framework for providing a format and focus for nursing phenomena. Later she has extended carative to caritas and caritas processes.24 The Caring Behaviors Inventory (CBI), developed by Wolf (1986). The conceptual-theoretical basis was derived from caring literature in general, and Watson's (1988) transpersonal caring theory, in particular.4

MethodsStudy design and participantsThis cross-sectional, descriptive, and analytical study was carried out from December 2012 to April 2013, and the study population was selected from nurses working and patients admitted to CCUs and ICUs. Assuming α=0.05, β=0.10, d=10.00, Z1−α=1.96, Z1−β=1.28, the sample size of the patients was estimated to be 58; however, the sample size was set to be 70 with regard to the twenty-percent probability of sample attrition. The total number of nurses working in our settings was 70, so we used the census method to sample this population. The included patients were selected using a multi-stage quota sampling method. To this end, consecutive nonprobability sampling was conducted for the patients proportionate to the frequency of patients admitted to intensive care units in each city, and this type of sampling continued until the required sample was selected.

Inclusion criteria for the nurses were having at least six months of work experience in intensive care units, working in intensive care units during the research period, having an associate or undergraduate/postgraduate degree in nursing. Exclusion criteria for the nurses were unwillingness to collaborate. Inclusion criteria for the elderlies were being aged 60 years and above, admitted to intensive care units for more than 24h, and fully conscious, and having no cognitive problems, the ability to communicate verbally, and hemodynamic stability. Exclusion criteria for the elderlies were unwillingness to collaborate and hemodynamic and respiratory instability.

Data collection instrumentsData collection instruments were as follows: A. Demographic and professional characteristics of nursing staff questionnaire, which addressed variables such as age, gender, marital status, degree, work experience, and the ward where the participant was working; B. Demographic questionnaire of elderly patients admitted to intensive care units, which addressed variables such as age, gender, marital status, level of education, the ward where the participant was admitted, length of hospitalization, disease diagnosis, and frequency of hospitalization; C. Caring Behavior Inventory for Elders (CBI-E): This instrument was developed by Wolf et al. (2004, revised 2006)25,26 as a self-administered tool to measure elders’ perceptions of nurse caring behaviors. It is a valid and reliable inventory compromises which displays different nurse caring behaviors including attending to individual needs, showing respect, practicing knowledgeably and skillfully respecting autonomy and supporting religious/spiritual needs. The original version of this tool encompassed 28 items. This qualitative and quantitative face validity of the questionnaire was assessed. Moreover, the content validity index (CVI) of this inventory was assessed by 10 faculty members at Lorestan University of Medical Sciences. Accordingly, four items were removed from CBI-E, and the final version consisted of 24 items. Regarding its internal consistency, Cronbach's alpha coefficient was estimated to be 0.71. The questionnaire was scored based on a three-point Likert scale (rarely=0, sometimes=50, often=100), with minimum and maximum scores of zero and 100, respectively. The higher scores representing a higher perception of nurse caring behavior.

Protection of human subjectsEthical approval was obtained for our study from the Ethics Committee of the Lorestan University of Medical Sciences, Khorramabad, Iran. Permissions were obtained from the hospitals and units authorities. Participants were informed about the purpose and course of the study, and that they were free to withdraw from participation in the study if they wished so. Participants were also assured about the confidentiality of the data, absence of any constraint to participate. They were also asked to complete a written informed consent form prior to enrollment in the study.

ProcedureThe researcher referred to the concerned hospitals during different work shifts. The nurse questionnaires were completed by the nurse, and the patient questionnaire items were asked from patients by a questioner who was a nursing student and were then written down on the questionnaire form. Data were collected from two hospitals and six intensive care units.

Data analysisAfter extracting the required data from the questionnaires, the data were analyzed using descriptive statistics in SPSS software version 17. Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to test the normality of the variables. Non-parametric tests such as; Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used in the case of the non-normal distribution of the study variables, and Spearman's correlation coefficient was obtained to assess the relationships. Furthermore, independent sample t-test was also run to compare the patients and nurses’ mean scores. Significance level was set to be <0.5 in all the aforementioned tests.

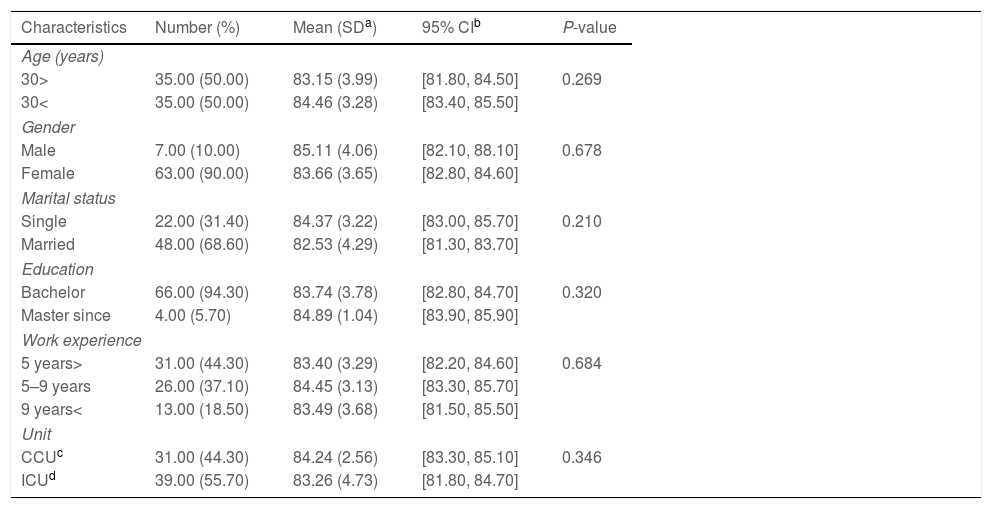

ResultsIn each group, 70 persons completed the questionnaires. The mean age of nurses was 30.00 (24.00), 95% CI [24.40, 35.60] years, most of them were female (90%) and the mean work experience of 6.00 (15.00), 95% CI [2.49, 9.51] years (Table 1). In the group of the elderlies, a majority of these patients were female (54.3%), and their mean age was 70.00 (32.00), 95% CI [62.50, 77.50] years (Table 2). Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests revealed no statistically significant difference between nurses’ age groups (P=0.269), gender (P=0.678), level of education (P=0.320), marital status (P=0.210), work place (P=0.346), and work experience (P=0.684) with regard to the scores of caring behaviors. Furthermore, Spearman's correlation coefficient revealed no significant linear relationship between age groups (P=0.249), level of education (P=0.548), and work experience (P=0.733).

Demographic information of nurses and the relationship between the mean score of perception of caring behavior and demographic information.

| Characteristics | Number (%) | Mean (SDa) | 95% CIb | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| 30> | 35.00 (50.00) | 83.15 (3.99) | [81.80, 84.50] | 0.269 |

| 30< | 35.00 (50.00) | 84.46 (3.28) | [83.40, 85.50] | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 7.00 (10.00) | 85.11 (4.06) | [82.10, 88.10] | 0.678 |

| Female | 63.00 (90.00) | 83.66 (3.65) | [82.80, 84.60] | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 22.00 (31.40) | 84.37 (3.22) | [83.00, 85.70] | 0.210 |

| Married | 48.00 (68.60) | 82.53 (4.29) | [81.30, 83.70] | |

| Education | ||||

| Bachelor | 66.00 (94.30) | 83.74 (3.78) | [82.80, 84.70] | 0.320 |

| Master since | 4.00 (5.70) | 84.89 (1.04) | [83.90, 85.90] | |

| Work experience | ||||

| 5 years> | 31.00 (44.30) | 83.40 (3.29) | [82.20, 84.60] | 0.684 |

| 5–9 years | 26.00 (37.10) | 84.45 (3.13) | [83.30, 85.70] | |

| 9 years< | 13.00 (18.50) | 83.49 (3.68) | [81.50, 85.50] | |

| Unit | ||||

| CCUc | 31.00 (44.30) | 84.24 (2.56) | [83.30, 85.10] | 0.346 |

| ICUd | 39.00 (55.70) | 83.26 (4.73) | [81.80, 84.70] | |

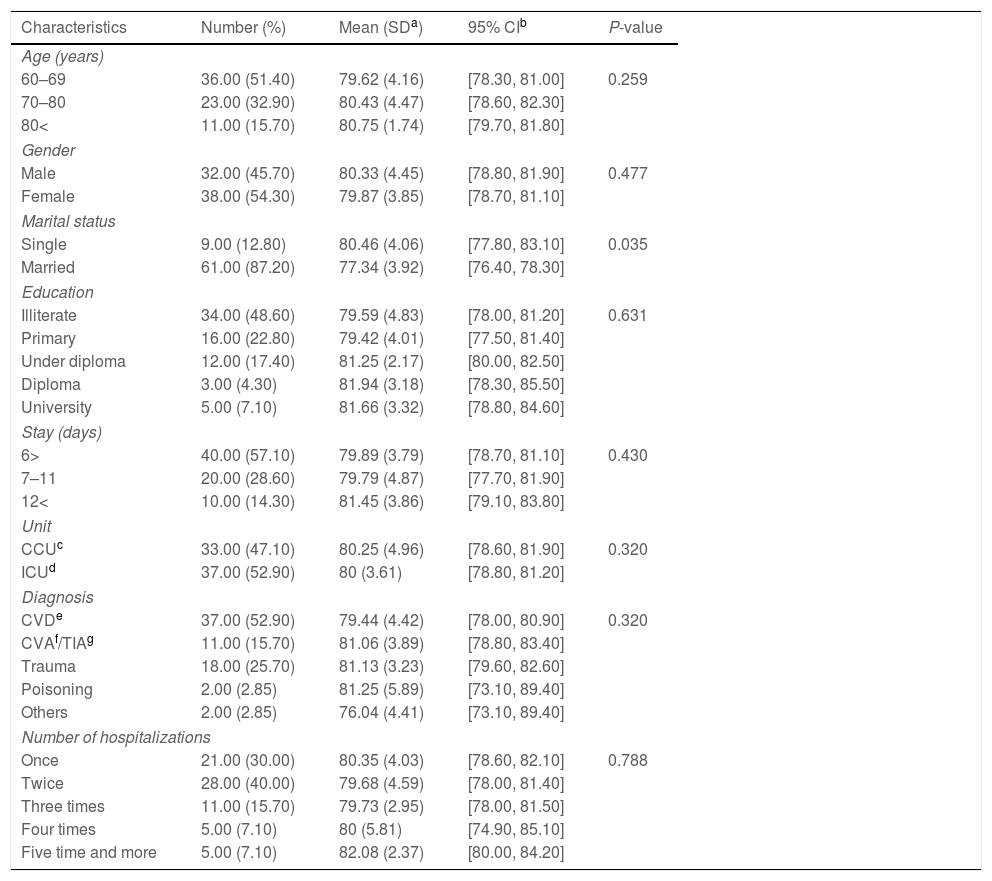

Demographic information of elderly patients and the relationship between the mean score of perception of caring behavior and demographic information.

| Characteristics | Number (%) | Mean (SDa) | 95% CIb | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| 60–69 | 36.00 (51.40) | 79.62 (4.16) | [78.30, 81.00] | 0.259 |

| 70–80 | 23.00 (32.90) | 80.43 (4.47) | [78.60, 82.30] | |

| 80< | 11.00 (15.70) | 80.75 (1.74) | [79.70, 81.80] | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 32.00 (45.70) | 80.33 (4.45) | [78.80, 81.90] | 0.477 |

| Female | 38.00 (54.30) | 79.87 (3.85) | [78.70, 81.10] | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 9.00 (12.80) | 80.46 (4.06) | [77.80, 83.10] | 0.035 |

| Married | 61.00 (87.20) | 77.34 (3.92) | [76.40, 78.30] | |

| Education | ||||

| Illiterate | 34.00 (48.60) | 79.59 (4.83) | [78.00, 81.20] | 0.631 |

| Primary | 16.00 (22.80) | 79.42 (4.01) | [77.50, 81.40] | |

| Under diploma | 12.00 (17.40) | 81.25 (2.17) | [80.00, 82.50] | |

| Diploma | 3.00 (4.30) | 81.94 (3.18) | [78.30, 85.50] | |

| University | 5.00 (7.10) | 81.66 (3.32) | [78.80, 84.60] | |

| Stay (days) | ||||

| 6> | 40.00 (57.10) | 79.89 (3.79) | [78.70, 81.10] | 0.430 |

| 7–11 | 20.00 (28.60) | 79.79 (4.87) | [77.70, 81.90] | |

| 12< | 10.00 (14.30) | 81.45 (3.86) | [79.10, 83.80] | |

| Unit | ||||

| CCUc | 33.00 (47.10) | 80.25 (4.96) | [78.60, 81.90] | 0.320 |

| ICUd | 37.00 (52.90) | 80 (3.61) | [78.80, 81.20] | |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| CVDe | 37.00 (52.90) | 79.44 (4.42) | [78.00, 80.90] | 0.320 |

| CVAf/TIAg | 11.00 (15.70) | 81.06 (3.89) | [78.80, 83.40] | |

| Trauma | 18.00 (25.70) | 81.13 (3.23) | [79.60, 82.60] | |

| Poisoning | 2.00 (2.85) | 81.25 (5.89) | [73.10, 89.40] | |

| Others | 2.00 (2.85) | 76.04 (4.41) | [73.10, 89.40] | |

| Number of hospitalizations | ||||

| Once | 21.00 (30.00) | 80.35 (4.03) | [78.60, 82.10] | 0.788 |

| Twice | 28.00 (40.00) | 79.68 (4.59) | [78.00, 81.40] | |

| Three times | 11.00 (15.70) | 79.73 (2.95) | [78.00, 81.50] | |

| Four times | 5.00 (7.10) | 80 (5.81) | [74.90, 85.10] | |

| Five time and more | 5.00 (7.10) | 82.08 (2.37) | [80.00, 84.20] | |

No statistically significant difference was also observed between the scores of caring behaviors and age groups (P=0.259), gender (P=0.477), level of education (P=0.631), type of disease (P=0.320), length of hospitalization (P=0.430), frequency of hospitalizations (P=0.788), place of hospitalization (P=0.320), and place of residence (P=0.934) among the elderly patients. In this group, Spearman's correlation coefficient test showed no significant linear relationship between the scores of caring behaviors with age groups (P=0.445), level of education (P=0.378), length of hospitalization (P=0.330) and frequency of hospitalization (P=0.885). There is no statistically significant difference in total mean scores of nurses and patients’ perceptions of caring behaviors (P=0.379) (Table 3).

Comparison of mean scores of nurses and patients’ perceptions of caring behaviors.

| Caregivers’ version | Mean (SDa) | 95% CIb | Elder version | Mean (SD) | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Listening carefully to a resident. | 97.14 (11.69) | [94.40, 99.90] | Listening carefully to you. | 82.14 (31.89) | [74.70, 89.60] | 0.001 |

| Helping a resident and his or her family make decisions. | 56.43 (22.39) | [51.20, 61.70] | Helping you and your family make decisions. | 37.14 (28.82) | [30.40, 43.90] | 0.000 |

| Being honest with a resident. | 56.43 (29.39) | [49.50, 63.30] | Being honest with you. | 52.14 (17.92) | [47.90, 56.30] | 0.246 |

| Assisting a resident to meet his or her religious or spiritual needs. | 87.14 (29.10) | [80.30, 94.00] | Assisting you to meet your religious or spiritual needs. | 91.43 (24.03) | [85.80, 97.10] | 0.346 |

| Helping a resident feel comfortable. | 100.00 (0.00) | [100.00, 100.00] | Helping you feel comfortable. | 97.86 (10.20) | [95.50, 100.00] | 0.081 |

| Recognizing how a resident feels | 56.43 (22.39) | [51.20, 61.70] | Recognizing how you feel. | 50.00 (25.53) | [44.00, 56.00] | 0.123 |

| Being patient with a resident. | 97.86 (10.20) | [95.50, 100.00] | Being patient with you. | 93.57 (20.71) | [88.70, 98.40] | 0.182 |

| Knowing how to give a resident treatments, needles, enemas, etc. | 100.00 (0.00) | [100.00, 100.00] | Knowing how to give you needles, enemas, treatments, etc. | 99.29 (5.97) | [97.90, 101.00] | 0.317 |

| Adjusting to a resident's limitations. | 90.00 (20.14) | [85.30, 94.70] | Adjusting to your limitations. | 90.00 (24.96) | [84.20, 95.80] | 0.598 |

| Speaking to a resident with a clear, friendly voice. | 90.00 (20.14) | [85.30, 94.70] | Speaking to you with a clear, friendly voice. | 94.29 (16.02) | [90.50, 98.00] | 0.165 |

| Knowing a resident's likes, dislikes, and routines. | 52.86 (30.55) | [45.70, 60.00] | Knowing your likes, dislikes, and routines. | 50.00 (28.23) | [43.40, 56.60] | 0.558 |

| Checking on a resident. | 100.00 (0.00) | [100.00, 100.00] | Checking on you frequently. | 97.86 (13.28) | [94.80, 101.00] | 0.156 |

| Being pleasant with a resident. | 100.00 (0.00) | [100.00, 100.00] | Being pleasant with you. | 98.57 (8.39) | [96.60, 101.00] | 0.156 |

| Including a resident when planning his or her care. | 22.86 (33.71) | [15.00, 30.80] | Including you when planning your care. | 14.29 (28.41) | [7.63, 20.90] | 0.093 |

| Protecting a resident's privacy. | 100.00 (0.00) | [100.00, 100.00] | Protecting your privacy. | 95.00 (17.34) | [90.90, 99.10] | 0.013 |

| Watching out for a resident's safety. | 100.00 (0.00) | [100.00, 100.00] | Watching out for your safety. | 99.29 (5.97) | [97.90, 101.00] | 0.317 |

| Meeting a resident's needs whether or not he or she asks. | 55.71 (27.64) | [49.20, 62.20] | Meeting your needs whether or not you ask. | 46.43 (24.55) | [40.70, 52.20] | 0.037 |

| Responding quickly to a resident's call. | 100.00 (0.00) | [100.00, 100.00] | Responding quickly to your call. | 100.00 (0.00) | [100.00, 100.00] | 1.000 |

| Appreciating a resident as a unique person. | 95.00 (15.10) | [91.50, 98.50] | Appreciating you as a unique person. | 93.57 (20.71) | [88.70, 98.40] | 0.955 |

| Managing a resident's pain. | 100.00 (0.00) | [100.00, 100.00] | Managing your pain. | 96.43 (15.51) | [92.80, 100.00] | 0.043 |

| Giving a resident's treatments and medicines on time. | 100.00 (0.00) | [100.00, 100.00] | Giving your treatments and medicines on time. | 99.29 (5.97) | [97.90, 101.00] | 0.317 |

| Trying to relieve a resident's ailments. | 100.00 (0.00) | [100.00, 100.00] | Trying to relieve your ailments. | 99.29 (5.97) | [97.90, 101.00] | 0.317 |

| Standing up for a resident's interests. | 53.57 (12.97) | [50.50, 56.60] | Standing up for your interests. | 45.71 (18.53) | [41.40, 50.00] | 0.005 |

| Giving a resident a hand when a he or she needs it. | 100.00 (0.00) | [100.00, 100.00] | Giving you a hand when you need it. | 98.57 (8.39) | [96.60, 101.00] | 0.156 |

| Total | 83.80 (22.93) | [78.40, 89.20] | Total | 80.09 (26.00) | [74.00, 86.20] | 0.379 |

The present cross-sectional, descriptive and analytical study aimed to compare nurses and patients’ perceptions of caring behaviors in intensive care units and explore different dimensions of such behaviors. The findings revealed no difference between nurses and elderly patients admitted to intensive care units in terms of their perceptions of nurses’ caring behaviors; however, they hold different perceptions with regard to listening to patients, helping patients and their families in decision making, meeting patients’ needs before they request, respect for privacy, being concerned with patients’ interests, and pain management.

According to the findings, the total mean score of the intensive care units nurses’ perceptions of nurses’ caring behaviors is high. Shalaby also reported high perception of caring behaviors among intensive care units nurses who had already received no training.2 Pajnkihar stated that the higher-level nurses had a better understanding of caring behaviors,27 implying high awareness levels among intensive care units nurses. In his proposed definition of nursing, Watson states that this science is the result of human, moral, scientific, personal, and professional interactions, the emergence of which requires an understanding of caring behaviors.28

The findings suggested that the nurses and elderly patients admitted to intensive care units had different perceptions of nurses’ caring behaviors; however, the difference was not statistically significant. In contrast with the findings of the present study, some other studies have documented patients and nurses’ different perceptions of nurses’ caring behaviors.18,29 In Papastavrou review study in 2011, she found no evidence documenting the difference between patients and nurses’ perceptions.18 The differences in the elderly patients and nurses’ perceptions of caring behaviors may be attributed to the lack of evaluation for the consequences of caring behaviors, high stress levels, and negative attitudes among the elderly and would result in the provision of care services, which are not of priority for the elderly, thereby promoting dissatisfaction among the elderly.30 Accordingly, nurses need to prioritize caring behaviors tailored to the patient's needs.

The study findings also highlighted the significance of listening to patients for nurses, while the elderly hold different perceptions in this regard. This inconsistency may be caused by the fact that the intensive care units nurses, despite their heavy workload and limited time, usually listen to their patients during the caring procedure; however, the patients may feel vice versa, leading to such a different perception. Furthermore, since this nursing behavior obtained high scores from the nurses, it seems that the nurses do not exhibit the necessary feedback to patients during other caring behaviors, and this leads to an inconsistency in nurses and elderly patients’ perceptions. In Omri's study, nurses self-reported that one of their main caring behaviors is to listen to patients.29

According to the findings, nurses and the elderly patients have different perceptions regarding the involvement of the patients’ families in decision-making. Omari claimed that patients’ families usually perceive physicians as the ones who can answer their questions and inform them of their patients’ treatment process. This in turn enhances the distance between nurses and patients’ families.29 Nurses are also recommended to adopt a holistic view to patients, perceive patients’ families as a part of the care process, and exploit these families in the decision-making process to take care of the elderly. A study examined and compared the perceptions of nurses and patients’ families and revealed their similar perceptions of caring behaviors,1 confirming the capability of the elderly families to make caring decisions.

The research findings also highlighted the one-hundred-percent significance of respect for patients’ privacy by nurses even though the nurses and patients’ perception of this caring behavior differed. A majority of previous studies have also confirmed that patients’ privacy is not well-respected.31–33 Respect for privacy is a fundamental human right. Given the critical condition of intensive care units patients and their need for a variety of caring measures, as one of the intensive care units nurses’ main obligations, the nurses may expect to have a full and unlimited access to these patients, and their definition of privacy would be different from that of the public. Consequently, this issue would raise a difference in nurses and elderly patients’ perceptions.

According to the nurses, they pay attention and track half of their patients’ needs without the patients’ request; however, the elderly hold a different perception stating that less than half of their needs are met without their request. Given many psychological, mental, and physiological needs of the elderly patients in intensive care units and different needs of these patients, nurses fail to predict and respond to all the needs of these elderly patients. Regarding the communication problems existing among the elderly, nurses should be able to well-respond to these needs.

All the nurses noted that they were concerned with patients’ pain management, while patients’ perceptions of this issue varied significantly. The nurses’ lack of complete independence in pain management can be a critical factor affecting the inadequate management of patients’ pain. Consistent with this finding, in Coker's study, nurses reported the main barriers in managing the elderly's pain is difficulty assessing pain in older people due to problems with cognition; inadequate time to deliver nonpharmacological pain relief measures; and patients reporting their pain to the doctor, but not to the nurse.34 Accordingly, nurses are suggested to be in charge of managing acute pain in patients. The same has happened in Poland, where managing acute pain is entrusted to nurses under the supervision of an anesthesiologist.8 In the study of Yarahmadi's study in Iran, nurses manage the pain of patients in the intensive care unit.35

Nurses perceived that attention to patients’ interests was not a priority for nurses. While the score of perceived behavior in patients is also lower than the score perceived by nurses. In addition to knowledge and skills and in accordance with ethical codes, nurses should pay further attention to different aspects of human behavior and patients’ interests in providing care services.36

The findings also revealed that attention to patients’ spiritual needs is one of the main behaviors perceived by patients. The patients and nurses hold similar perceptions in this regard. Given that a high percentage of Iranian population are Muslims, such a common perception was expected. For Muslims, expressing religious feelings, beliefs, and behaviors is considered as a perceived spiritual need.

All the nurses stated that some measures such as patient comfort, how to treat and timely treatment, frequent patient examinations, patient safety, quick response to patients’ calls, patients’ pain management and relief, and helping patients in times of need are of paramount important, implying that, in line with the patients’ needs, the nurses are concerned with the patients’ physical and physiological needs. According to Maslow's pyramid, these needs have a priority over other needs.2 Other studies have also confirmed that this dimension of needs is of greater important to nurses.18,37 These findings are inconsistent with those of O’Connell's study, according to whom the highest score for nurses’ caring is obtained for human factors, beliefs, and hope.38 The nurses highlighted the significance of patient safety to them as it is concerned in all their caring behaviors. The patients provided responses similar to the nurses’, and this may be due to the nurses’ awareness of the elderly patients’ vulnerability in intensive care units and the significance of providing safety and protection for these patients under stressful conditions. These findings confirm those proposed by Shalay.2

In this study, the elderly perceived that the intensive care units nurses were kind to them, understood their feelings, were honest, were concerned with their spiritual needs, were patient, talked friendly, and paid attention to the elderly as important persons, indicating that nurses have kindly integrated human emotions and nursing art in their care services and are concerned with the human aspects of caring. Watson believes that nursing should be comprehensive and, in addition to physical needs, consider patients’ psychological, social, and spiritual needs and be accompanied with the spiritual aspects of patients’ lives. Nurses should adopt a comprehensive and patient-centered nursing theory in their caring process.27

The finding of the present study revealed that all the questionnaires were completed and answered by the patients, implying that nurses’ behavior is fully and constantly observed by patients and that patients continuously judge such care providers. Accordingly, nurses should always self-assess their caring behaviors. To sum up, the study findings suggest that the intensive care units nurses should be well aware of the aspects which are of great important to the elderly so that the elderly would feel good. In this regard, the common perception of the elderly and nurses regarding caring behaviors would promote the quality of nursing care.21

This study simultaneously assessed nurses’and patients’ perceptions with a same instrument.

The tool used is a valid tool and has been translated into Persian by the back translation process and examined in terms of validity and reliability in the Persian community. However, due to the impact of culture and context on people's perceptions of caring behaviors, the development of a native tool to study caring behaviors for elderly patients can help to produce valid data.

ConclusionAccording to the study findings, nurses and elderly patients’ perceptions of caring behaviors is somehow similar, thereby helping nurses to correctly prioritize their patients’ care needs. Given that the research was conducted in intensive care units and with regard to the patients’ critical conditions, the caring behaviors, which are associated with physical-technical dimensions, have received more attention; however, more study is needed to support this finding.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.

We are grateful to the nurses and patients who participated in this study.