There is controversy regarding the effectiveness of chest physiotherapy to solve airway obstruction problems experienced by children younger than five years of age with pneumonia. The aim of this study was to determine the effectiveness of chest physiotherapy and nebulization on the respiratory status of these children.

MethodThis study was quasi-experimental with a pre- and post-test nonequivalent control group design. Thirty-four respondents selected by consecutive sampling were divided into two groups: one that received nebulization and one that received nebulization with chest physiotherapy. The independent t-test was used to analyze the effect of chest physiotherapy and nebulization on the respiratory status of children younger than age five with pneumonia.

ResultsThere was a significant mean difference in heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation between the control and intervention group (p=0.000). Despite the correlation between age and heart rate, other characteristics (nutritional status, exclusive breast-feeding, vaccination, the length of illness, and the content of nebulization medication) had no effect on heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation.

ConclusionsThe combination of nebulization and chest physiotherapy is more effective than nebulization only. It is important to reconsider the combination of nebulization and chest physiotherapy to overcome airway obstruction problems.

Infant mortality is one of the parameters of a country’s health. In 2015, approximately 922,000 (15%)1 deaths among children younger than age five were caused by pneumonia. In the same year, pneumonia was the second-highest cause of death among infants and toddlers in Indonesia, with diarrhea being the first. It is also listed as one of the ten most dangerous diseases in health facilities each year2. In 2013 in Indonesia, approximately 14%3 of children’s deaths were due to pneumonia. This shows that pneumonia is still the main health concern within communities, and it is one of the factors contributing to the high child mortality rate in Indonesia2.

Between 7-13% of pneumonia cases in the community become severe and require hospitalization4. Children with pneumonia encounter various problems during hospitalization (e.g., respiratory distress due to increasing secretion production)5,6. Children with pneumonia often experience difficulty releasing secretions because their cough reflexes are weak at their young age5. Alternative treatments that can overcome the accumulation of secretions are nebulization and chest physiotherapy7. The study showed that providing nebulization in the intensive care unit to patients with atelectasis and pneumonia could prevent blockage in the respiratory tract due to excessive sputum production8.

Giving chest physiotherapy is still a controversial issue. The previous study demonstrated that chest physiotherapy was not effective9,10. Nevertheless, chest physiotherapy continues to provide benefits by reducing several respiratory symptoms in children, such as coughing and difficulty breathing.

Another study explained that chest physiotherapy could in fact offer some benefits. A study on the impact of chest physiotherapy in children showed that it reduced the number of days hospitalized for a child with no record of chronic respiratory illness11. Another study showed how a child could not yet coordinate the release of secretions through passive techniques, such as as percussion, vibration, and postural drainage—more commonly known as conventional physical therapy (CPT)12. Conversely, another study showed that CPT could reduce secretions and increase oxygenation12. Based on these findings, this study aimed to determine the effectiveness of chest physiotherapy and nebulization on the respiratory status of children under the age of five with pneumonia.

MethodThis study used a quasi-experimental design with pre- and post-tests and nonequivalent control group design, which includes two groups. The respondents were selected using consecutive sampling techniques. The samples of this study were children ages 0-59 months, consisting of 17 respondents in the control group and 17 respondents in the intervention group. The instruments used to collect data in this study were observation sheets, pulse oximetry, and a respiratory rate timer.

Children’s heart rates, respiratory rates, and oxygen saturations were measured for twenty minutes before the treatment was given. The respondent had just received nebulization therapy for the first time; this procedure was followed by one-time nebulization (based on standard operational procedure) for a specific time period, depending on the characteristics of the medicine in both groups. The study assistant (physiotherapist) was the one performing the chest physiotherapy. Chest physiotherapy was given for thirty minutes in the treatment room. Chest physiotherapy was given before meals or 1 to 1.5 hour after meals to minimize vomiting. After treatment was given, the study assistant noted the respiratory status on the observation sheet, including heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation. The measurement was undertaken after 20 minutes of treatment13. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Nursing of Universitas Indonesia and Hospital. The data analyses were univariate, bivariate, and multivariate using the independent t-test.

ResultsThe average age of the respondents in the intervention group was younger (13.24 months) than that of the respondents in the control group (22.65 months). The average length of sickness of respondents in the control group was higher than that of respondents in the intervention group by 4.76 days and 4.47 days.

Wiht regard to nutritional status, there were 76.5% in the control group had poor nutritional status, while 64.7% in the intervention group had poor nutritional status. There were more respondents in the control group who were breast-fed exclusively (70.6%), whereas in the intervention group, more respondents were not exclusively breast-fed (58.8%). The immunization status in both groups that did not receive complete immunization was lower (by 11.8% and 17.6%, respectively) than the ones who did receive complete immunization. The classification of pneumonia in the control group and the intervention group was 100%.

Respondents in the control and the intervention groups did not use oxygen. The content of nebulization in the control group (52.9%) and the intervention group (58.8%) that received bronchodilation, mucolytics, and NaCl was higher than that of the group that received only bronchodilation and mucolytics.

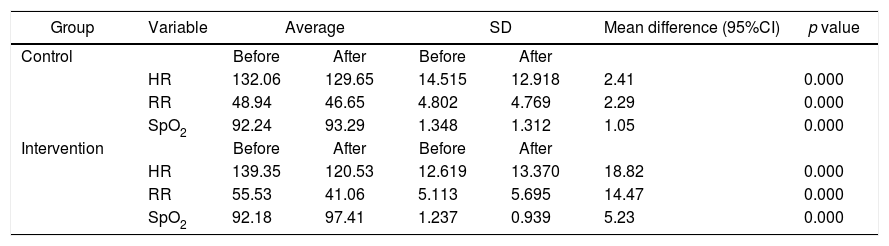

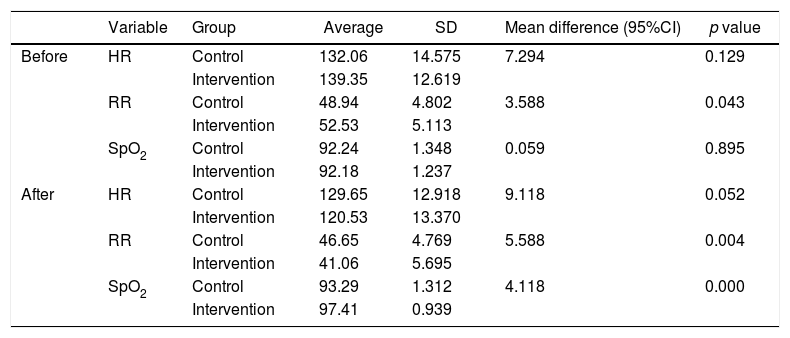

As shown in Table 1, heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation before and after treatment increased in both groups with higher increases in the intervention group. This result showed that there was a difference in heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation before and after treatment in the control group and in the intervention group (p=0.000, a=0.05). Table 2 shows that there was no difference before treatment in heart rate and oxygen saturation between the control group and the intervention group (p > 0.05) and no difference between the control group and the intervention group in respiratory frequency (p < 0.05). Although no difference was found in heart rates after treatment, there was a difference in respiratory rates and oxygen saturations between the control group and the intervention group (p < 0.05). This study revealed a significant difference in respiratory status between the control group and the intervention group; the respiratory rates of the intervention group were higher than those of the control group (p=0.000, a=0.05).

The mean difference in respiratory status before and after treatment in the control group and the intervention group in RSUD Tegal, May-June 2016 (n=34).

| Group | Variable | Average | SD | Mean difference (95%CI) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Before | After | Before | After | |||

| HR | 132.06 | 129.65 | 14.515 | 12.918 | 2.41 | 0.000 | |

| RR | 48.94 | 46.65 | 4.802 | 4.769 | 2.29 | 0.000 | |

| SpO2 | 92.24 | 93.29 | 1.348 | 1.312 | 1.05 | 0.000 | |

| Intervention | Before | After | Before | After | |||

| HR | 139.35 | 120.53 | 12.619 | 13.370 | 18.82 | 0.000 | |

| RR | 55.53 | 41.06 | 5.113 | 5.695 | 14.47 | 0.000 | |

| SpO2 | 92.18 | 97.41 | 1.237 | 0.939 | 5.23 | 0.000 | |

The mean difference in respiratory status before and after treatment between the control group and the intervention group in RSUD Tegal, May-June 2016 (n=34).

| Variable | Group | Average | SD | Mean difference (95%CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | HR | Control | 132.06 | 14.575 | 7.294 | 0.129 |

| Intervention | 139.35 | 12.619 | ||||

| RR | Control | 48.94 | 4.802 | 3.588 | 0.043 | |

| Intervention | 52.53 | 5.113 | ||||

| SpO2 | Control | 92.24 | 1.348 | 0.059 | 0.895 | |

| Intervention | 92.18 | 1.237 | ||||

| After | HR | Control | 129.65 | 12.918 | 9.118 | 0.052 |

| Intervention | 120.53 | 13.370 | ||||

| RR | Control | 46.65 | 4.769 | 5.588 | 0.004 | |

| Intervention | 41.06 | 5.695 | ||||

| SpO2 | Control | 93.29 | 1.312 | 4.118 | 0.000 | |

| Intervention | 97.41 | 0.939 |

The results of the bivariate analysis showed a correlation between age and heart rate (p < 0.05), whereas the other variables showed no meaningful correlation (p > 0.05). The results of the multivariate analysis revealed a correlation in relation to age, exclusive breast-feeding, and respiratory rate and also in relation to age, exclusive breast-feeding, and oxygen saturation. The respiratory rate=10.946 + (−0.136 age) +(−2 exclusive breast-feeding). Age and exclusive breast-feeding were determined to be negative, which means that the higher the age and the status of exclusive breast-feeding, the lower the respiratory rate. Oxygen saturation=5.078 + (−0.053 age) + (−1.764 exclusive breast-feeding). It was determined that the results of age and exclusive breast-feeding were negative, which means that the higher the age and the status of exclusive breast-feeding, the lower the oxygen saturation.

DiscussionThe study revealed differences in respiratory status (heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation) before and after treatment between the control group and the intervention group. This means that nebulization and chest physiotherapy were crucial to the respiratory status of children under five of age with pneumonia.

The results of this study differed from those of the previous one, which stated chest physiotherapy was not too effective for children who have bronchiolitis9. Another study found that chest physiotherapy provided only small benefits through a number of respiratory symptoms in the stoppage of bronchiolitis in children with acute respiration problems10. This may be because general techniques for chest physiotherapy were used in that study. Another study also explained that chest physiotherapy had no effect on the length of the healing process14.

The previous study revealed that one benefit of chest physiotherapy was that it helped reduce the number of days a child was hospitalized11. Another study showed that passive techniques, such as percussion, vibration, and postural drainage (more commonly known as CPT) reduced secretions and increased oxygenation12. Chest physiotherapy was used in the procedural arrangement of passive treatment for patients with bronchiolitis and pneumonia. One indication of chest physiotherapy was the increase of secretion. The technique for chest physiotherapy was proven effective and safe15.

The benefit of nebulization was that it increased mucociliary clearance16. The study explained that providing nebulization prevents stoppage in the respiratory tract due to the excessive production of sputum8. Another study revealed that providing salbutamol nebulization to children with acute bronchiolitis was effective in reducing the number of days hospitalized and improved the clinical severity score17. A similar study on nebulization asserted that providing salbutamol nebulization to patients with acute bronchial asthma reduced their heart rates and increased oxygen saturation18.

The mean difference in heart rate before and after treatment was higher in the intervention group than in the control group, which was 18.82x/minute and 2.41x/minute. This means that combination nebulization and chest physiotherapy was proven more effective than nebulization treatment only. Similar results occurred with respiratory rates in children with pneumonia who were under the age of five, with rates of 14.47x/minute and 2.29x/minute. For children under the age of five with pneumonia, it was common for secretions to accumulate because there was obstruction in the upper and lower respiratory tracts due to increased heart and respiratory rates. Thus, combination nebulization and chest physiotherapy had a positive impact because it stabilized or normalized heart and respiratory rates. This was in line with the previous study, which described the possibility of significant improvement towards heart and respiratory rates after chest physiotherapy19,20.

The mean oxygen saturation, before and after treatment in the intervention group, was higher than that in the control group by 5.23% and 1.05%. This result corresponded to the previous study in that the average of oxygen saturation in toddlers improved after chest physiotherapy21. Another similar study explained that chest physiotherapy affected oxygen saturation22. Another study in Brazil also revealed that patients who underwent chest physiotherapy experienced an increase in oxygen saturation20. Chest physiotherapy included postural drainage, vibration, and percussion7. Postural drainage took place if there was excessive fluid or mucus that could not be released through normal silia activity and coughing. Positioning the child to obtain a benefit from gravity could help release secretions. Postural drainage could be effective for children who had lung disease with thick secretions, so when such children were free of accumulation of secretions, the respiratory tract cleared more effectively23.

The study revealed that combination nebulization and chest physiotherapy had positive effects on heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation. The study results can be considered to be included in the hospital guidelines to encourage nurses to conduct nebulization, followed by chest physiotherapy. As a result of the study, it is advised that evidence-based practices be developed in nursing practice in regard to nebulization and chest physiotherapy; and that the combination of nebulization and chest physiotherapy is safe and beneficial.

I would like to thank Dessie Wanda, S.Kp., MN., PhD; the study respondents and their parents, the Head of the Room RSUD Kardinah, and RSUD Dr. Soeselo Tegal, the study assistant.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.