Almost 281 million people were living in a foreign country in 2022, and more than 100 million were displaced because of war conflicts and human right violations. Vaccination coverage of infectious diseases in migrants from some disadvantaged settings could be lower than reception countries populations, consequently seroprevalence studies and better access to vaccination could contribute to reducing these differences.

MethodsA descriptive retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted including migrants, living ≤5 years in the reception country and ≥16 years old, who requested a medical exam between January 1st, 2020 and January 31st, 2021. Seroprevalence assessment was performed, and vaccination was offered to those individuals without immunity to hepatitis B, hepatitis A, varicella, measles, mumps, and rubella.

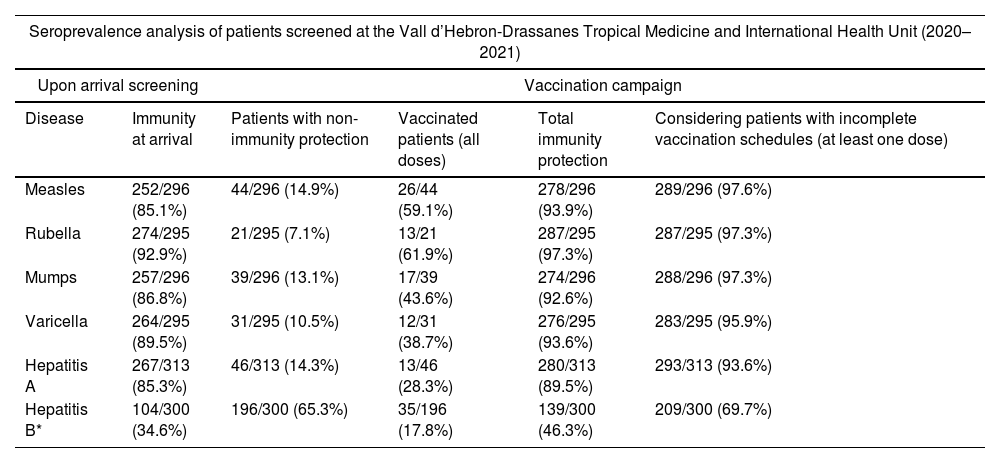

ResultsA total of 315 migrants were attended during the study period. Immunity protection at arrival was 252/296 (85.1%) for measles, 274/295 (92.9%) for rubella, 257/296 (86.8%) for mumps, 264/295 (89.5%) for varicella, 267/313 (85.3%) for hepatitis A, and 104/300 (34.6%) for hepatitis B. The final immunity protection after full vaccination schedules was 278/296 (93.9%) for measles, 287/295 (97.3%) for rubella, 274/296 (92.6%) for mumps, 276/295 (93.6%) for varicella, 280/313 (89.5%) for hepatitis A, and 139/300 (46.3%) for hepatitis B.

ConclusionsThe vaccination intervention has increased immunity rates for the studied diseases in the attended migrants in our center, however, such interventions should be maintained to reach local population immunization levels. Moreover, the collaboration between shelter and reference specialized health centers is fundamental to implement such vaccination programs.

En 2022, alrededor de 281 millones de personas vivían en un país extranjero y más de 100 millones fueron desplazados de su país de origen. La cobertura vacunal frente a enfermedades infecciosas en migrantes recién llegados (MRL) es inferior a la de las poblaciones de los países de acogida. Por consiguiente, los estudios de seroprevalencia y un mejor acceso a la vacunación contribuyen a reducir estas diferencias.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio descriptivo retrospectivo transversal incluyendo a los migrantes, que residieron ≤5 años en el país de acogida y con ≥16 años de edad, que solicitaron un examen médico entre el 1 de enero de 2020 y el 31 de enero de 2021. Se ofreció análisis serológico y vacunación a aquellos individuos sin inmunidad frente a hepatitis B (HBV), hepatitis A (HAV), varicela, sarampión, parotiditis y rubéola.

ResultadosTrescientos quince migrantes fueron atendidos durante el periodo de estudio. Las tasas de protección iniciales fueron de 252/296 (85,1%) para sarampión, 274/295 (92,9%) para rubéola, 257/296 (86,8%) para parotiditis, 264/295 (89,5%) para varicela, 267/313 (85,3%) para HAV y 104/300 (34,6%) para HBV. La protección final tras las pautas de vacunación completas fue de 278/296 (93,9%) para sarampión, 287/295 (97,3%) para rubéola, 274/296 (92,6%) para parotiditis, 276/295 (93,6%) para varicela, 280/313 (89,5%) para HAV y 139/300 (46,3%) para HBV.

ConclusionesLa intervención ha aumentado las tasas de inmunidad en los migrantes, sin embargo, dichas acciones deben mantenerse para alcanzar los niveles de inmunización de la población local. La colaboración entre centros de acogida y centros sanitarios especializados de referencia es fundamental para implementar los programas de vacunación.

The number of international migrants has been rising over the last decades. In 2020, almost 281 million people were living in a foreign country, and more than 82 million were displaced because of war conflicts and human right violations.1 This number rises to 100 million people in 2022, and is expected to continue increasing.2 Spain is one of the border states of the European Union that receives the highest percentage of irregular arrivals of migrants through the maritime and land routes of the Western Mediterranean and West Africa.3

The geoepidemiology of migrants origin countries, migration route risks, and lifestyle changes in the foreign country confer significant health risks and increased vulnerability to acquiring infectious diseases.4 Several studies demonstrate that migration population subgroups are disproportionally affected by infectious diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV),5 and immunity coverage was below the recommended heard immunity thresholds for measles, mumps and rubella.6 It is important to note that the risk of migrant populations transmitting diseases to the host population is very low; however, poor life conditions or gaps in vaccination coverage could increase that risk.7 As a solution, the World Health Organization (WHO) Action Plan for Migrant and Refugee Health has the final objective of enabling the integration of migrant health requirements into national health programs.7 Reference regional European guides7,8 highlight the lack of information about the burden of infectious diseases in migrant populations, and the absence of standardized protocols.

Screening and immunization programs addressed to newly arrived migrants are priority preventive measures that allow the early initiation of treatment and reduce the burden and mortality of transmissible diseases, benefiting not only the patient but both the health care system and the general population.8 Therefore, migrant populations should be vaccinated without delay according to the national immunization schedules of the host country where they are expected to reside for over a week.7 Seroprevalence tests facilitate the study of immunity to certain vaccine-preventable diseases (VPD), and allow the recommendation of vaccination schedules for those patients who require it. European guidelines recommend offering screening and treatment for hepatitis B to migrants from intermediate/high prevalent countries (≥2% to ≥5% HBsAg), and offer vaccination for measles, mumps and rubella to adult migrants without immunization records.9 However, evidence based statements were not conclusive or show low evidence, demonstrating a lack of consensus on this type of interventions. Generally, in the European region the vaccination coverage of migrant populations is lower when compared with autochthonous populations.8 This situation may be explained by barriers to vaccination in their origin countries, misinformation, and cultural reasons. In addition, since the COVID-19 pandemic, global vaccination rates for other diseases have fallen dramatically.10 However, vaccination programs in host countries allow access to vaccination for migrant populations, and provide them with information on its benefits. Recent model vaccination impact studies predict that 51.5 million deaths are expected to be averted due to vaccination between 2021 and 2030, with measles (18.8 million) and HBV (14.0 million) as the most representative VPD.11 Moreover, similar studies reinforce this hypothesis with 69 million estimated deaths averted between 2000 and 2030.12

The purpose of this study is to describe the seroprevalence of six vaccine-preventable infectious diseases [HBV, hepatitis A (HAV), varicella, measles, mumps, and rubella] in migrants referred by shelter centers, and vaccination administration in our center according to serology test results.

Materials and methodsA descriptive retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted including all migrants, living ≤5 years in the reception country and ≥16 years old, who were referred by shelter centers for medical exam (with or without symptoms) at the International Health Center Drassanes-Vall d’Hebron (IHCDVH) in Barcelona (Spain) between January 1st, 2020 and January 31st, 2021

Since 2012, due to the situation of social vulnerability of migrant populations, there has been a framework agreement between shelter centers and the IHCDVH. This is a referral center in infectious diseases, with several years of experience with migrant populations.13 It also has a community health service that includes community health workers from most prevalent communities (Pakistan, Morocco, and Sub-Saharan Africa) who facilitate patient-provider communication in case of linguistic and cultural barriers, promotes health actions and activities with educational purposes at a community level. In cases where cultural mediators were not available, the 061 service (health telephone hotline, Catalonia) was employed to facilitate professional-patient communication.14

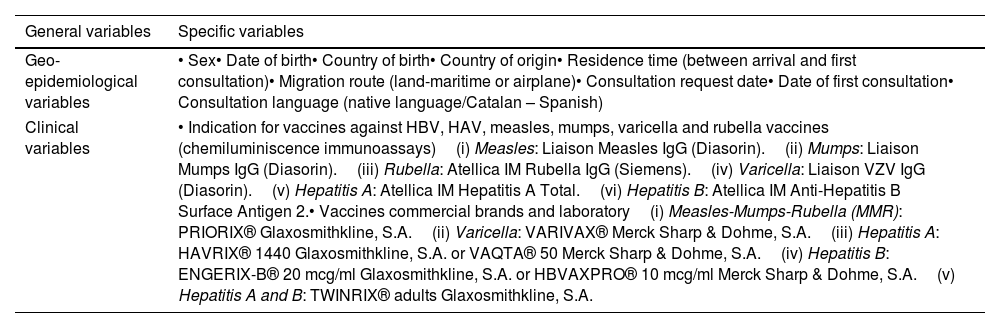

The content of this study was part of our migrants screening protocol based on national and international guidelines.9,15,16 The health protocol included: medical history, physical exam, geo-epidemiological history (migratory route and country of origin), the presence of symptomatology, and existence of previous clinical reports. A blood test analysis was performed, which included a serology test for HBV, HAV, varicella, measles, mumps, and rubella. Hepatitis B virus was tested in persons coming from countries with prevalence ≥2%, and in those cases in which other risk factors were present (sexual abuse, history of violence or prison, or sharing potentially contaminated materials). Vaccination was offered to those individuals without immunity to the studied diseases. The study variables and specifications of chemiluminiscence techniques are specified in Table 1.

Summary table of geo-epidemiological and clinical variables of the study.

| General variables | Specific variables |

|---|---|

| Geo-epidemiological variables | • Sex• Date of birth• Country of birth• Country of origin• Residence time (between arrival and first consultation)• Migration route (land-maritime or airplane)• Consultation request date• Date of first consultation• Consultation language (native language/Catalan – Spanish) |

| Clinical variables | • Indication for vaccines against HBV, HAV, measles, mumps, varicella and rubella vaccines (chemiluminiscence immunoassays)(i) Measles: Liaison Measles IgG (Diasorin).(ii) Mumps: Liaison Mumps IgG (Diasorin).(iii) Rubella: Atellica IM Rubella IgG (Siemens).(iv) Varicella: Liaison VZV IgG (Diasorin).(v) Hepatitis A: Atellica IM Hepatitis A Total.(vi) Hepatitis B: Atellica IM Anti-Hepatitis B Surface Antigen 2.• Vaccines commercial brands and laboratory(i) Measles-Mumps-Rubella (MMR): PRIORIX® Glaxosmithkline, S.A.(ii) Varicella: VARIVAX® Merck Sharp & Dohme, S.A.(iii) Hepatitis A: HAVRIX® 1440 Glaxosmithkline, S.A. or VAQTA® 50 Merck Sharp & Dohme, S.A.(iv) Hepatitis B: ENGERIX-B® 20 mcg/ml Glaxosmithkline, S.A. or HBVAXPRO® 10 mcg/ml Merck Sharp & Dohme, S.A.(v) Hepatitis A and B: TWINRIX® adults Glaxosmithkline, S.A. |

We gathered through medical records the sex, date of birth, country of birth, country of origin, arrival date, migration route, consultation request date, date of first consultation and language in which the anamnesis was conducted. The residence time in Spain was calculated using the date of the first consultation and the arrival date.

Immunological variablesVaccine administration data was obtained from System Analysis Programme (SAP) and Primary Care Clinical Station (ECAP) Catalan public health softwares. We considered immunity protection in patients with a positive serology result and patients vaccinated with the full vaccination schedule for the studied disease. Vaccination was indicated in patients with a negative serology result for the studied disease. Indication for HBV, HAV, measles, mumps, varicella and rubella vaccines were reported, beside the consequent number of doses administered for each one. Patients with incomplete vaccination schedule (at least one dose) for the studied diseases were considered, except for rubella which only requires one dose. Active infections of HBV were considered as non-immune individuals, and were excluded from the group of vaccination candidates (negative serology). The vaccines employed for this study are specified in Table 1.

Statistical analysisData analysis included measures of distribution, central tendency (median or average for normal distribution variables) and dispersion (standard deviation and interquartile range). Bivariate analysis of categorical variables was carried out using the Chi-squared test or the exact Fisher test for small samples. To compare continuous variables, the Student's t or the Mann Whitney U test were used. For the comparison of proportions in two or more groups we employed a univariate general linear model ANOVA test. Hypothesis testing was done with a 5% alpha risk and 95% confidence intervals. Logistic regression was performed to identify factors associated with the immunity to infectious diseases in migrants by sex (gender), age, geographical born region, time elapsed between arrival to Spain and consultation date, and migratory route. The statistical analysis was carried out using the SPSS 23.00® version 29.0.

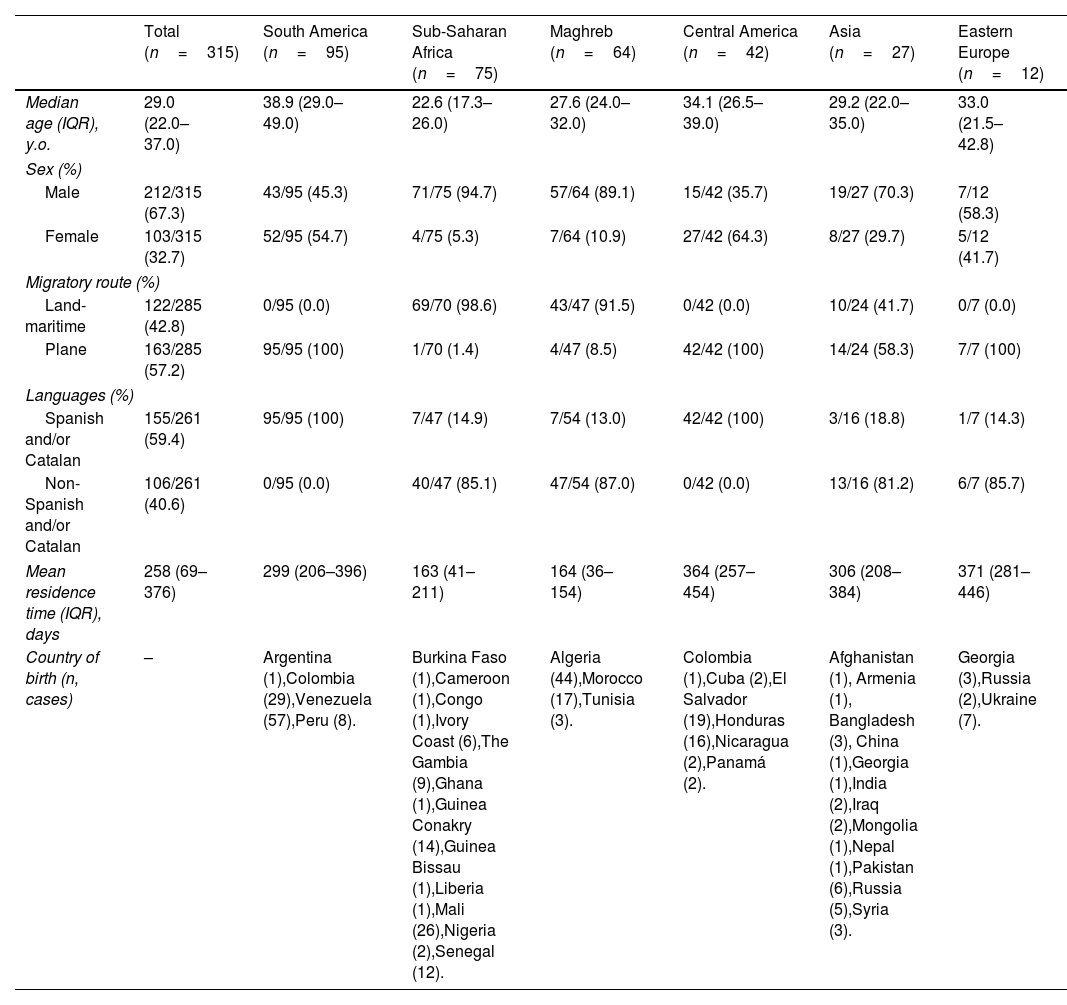

ResultsSociodemographic dataA total of 315 migrants were attended during the study period from 39 different nationalities. Their median age was 29 years [interquartile range (IQR): 22–37 years]; 28/315 individuals (8.9%) were between 16 and 18 years old, 221/315 (70.2%) were ≤35 years old. There were 212/315 (67.3%) male individuals and 103/315 (32.7%) female. Overall, 137/315 (43.5%) were from America, 75/315 (23.8%) from Sub-Saharan Africa, 64/315 (20.3%) from Maghreb, 27/315 (8.6%) from Asia, and 12/315 (3.8%) from Eastern Europe. The most widely represented country was Venezuela 57/315 (18.1%), followed by Algeria 44/315 (14.0%), Colombia 30/315 (9.5%), Mali 26/315 (8.3%), El Salvador 19/315 (6%), and Morocco 17/315 (5.4%). The median time elapsed between arrival to Spain and consultation date (mean residence time) was 258 days (IQR: 69–376). In 122/285 (42.8%) cases, the migration route to reach Spain was land-maritime and in 163/285 (57.2%) cases were by plane. The time elapsed between arrival to first consultation is significantly higher in Central America (364 days), Asia (306 days) and South America (299 days) individuals beside Maghreb (164 days) and Sub-Saharan Africa (163 days) individuals (p<0.01). Land-maritime migration was highly represented by Maghreb and Sub-Saharan Africa individuals 112/122 (91.8%). In 155/261 (59.4%) cases, the medical interview took place in Spanish or Catalan. However, 106/261 (40.6%) cases needed the use of other languages and in some occasions the support of community health workers or cultural mediators. Most patients from Sub-Saharan Africa 47/54 (87.0%), South America 40/47 (85.1%) and Asia 13/16 (81.2%) presented communication issues due to different native language speaking. Sociodemographic data information is presented in Table 2.

Summary sociodemographic data table of migrants from Drassanes-Vall d’Hebron Infectious Diseases and International Health Center during 2020–2021 by geographical born region (Asia, Eastern Europe, Central America, South America, Maghreb and Sub-Saharan Africa).

| Total (n=315) | South America (n=95) | Sub-Saharan Africa (n=75) | Maghreb (n=64) | Central America (n=42) | Asia (n=27) | Eastern Europe (n=12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (IQR), y.o. | 29.0 (22.0–37.0) | 38.9 (29.0–49.0) | 22.6 (17.3–26.0) | 27.6 (24.0–32.0) | 34.1 (26.5–39.0) | 29.2 (22.0–35.0) | 33.0 (21.5–42.8) |

| Sex (%) | |||||||

| Male | 212/315 (67.3) | 43/95 (45.3) | 71/75 (94.7) | 57/64 (89.1) | 15/42 (35.7) | 19/27 (70.3) | 7/12 (58.3) |

| Female | 103/315 (32.7) | 52/95 (54.7) | 4/75 (5.3) | 7/64 (10.9) | 27/42 (64.3) | 8/27 (29.7) | 5/12 (41.7) |

| Migratory route (%) | |||||||

| Land-maritime | 122/285 (42.8) | 0/95 (0.0) | 69/70 (98.6) | 43/47 (91.5) | 0/42 (0.0) | 10/24 (41.7) | 0/7 (0.0) |

| Plane | 163/285 (57.2) | 95/95 (100) | 1/70 (1.4) | 4/47 (8.5) | 42/42 (100) | 14/24 (58.3) | 7/7 (100) |

| Languages (%) | |||||||

| Spanish and/or Catalan | 155/261 (59.4) | 95/95 (100) | 7/47 (14.9) | 7/54 (13.0) | 42/42 (100) | 3/16 (18.8) | 1/7 (14.3) |

| Non-Spanish and/or Catalan | 106/261 (40.6) | 0/95 (0.0) | 40/47 (85.1) | 47/54 (87.0) | 0/42 (0.0) | 13/16 (81.2) | 6/7 (85.7) |

| Mean residence time (IQR), days | 258 (69–376) | 299 (206–396) | 163 (41–211) | 164 (36–154) | 364 (257–454) | 306 (208–384) | 371 (281–446) |

| Country of birth (n, cases) | – | Argentina (1),Colombia (29),Venezuela (57),Peru (8). | Burkina Faso (1),Cameroon (1),Congo (1),Ivory Coast (6),The Gambia (9),Ghana (1),Guinea Conakry (14),Guinea Bissau (1),Liberia (1),Mali (26),Nigeria (2),Senegal (12). | Algeria (44),Morocco (17),Tunisia (3). | Colombia (1),Cuba (2),El Salvador (19),Honduras (16),Nicaragua (2),Panamá (2). | Afghanistan (1), Armenia (1), Bangladesh (3), China (1),Georgia (1),India (2),Iraq (2),Mongolia (1),Nepal (1),Pakistan (6),Russia (5),Syria (3). | Georgia (3),Russia (2),Ukraine (7). |

IQR: interquartile range; y.o.: years old; n: number of cases.

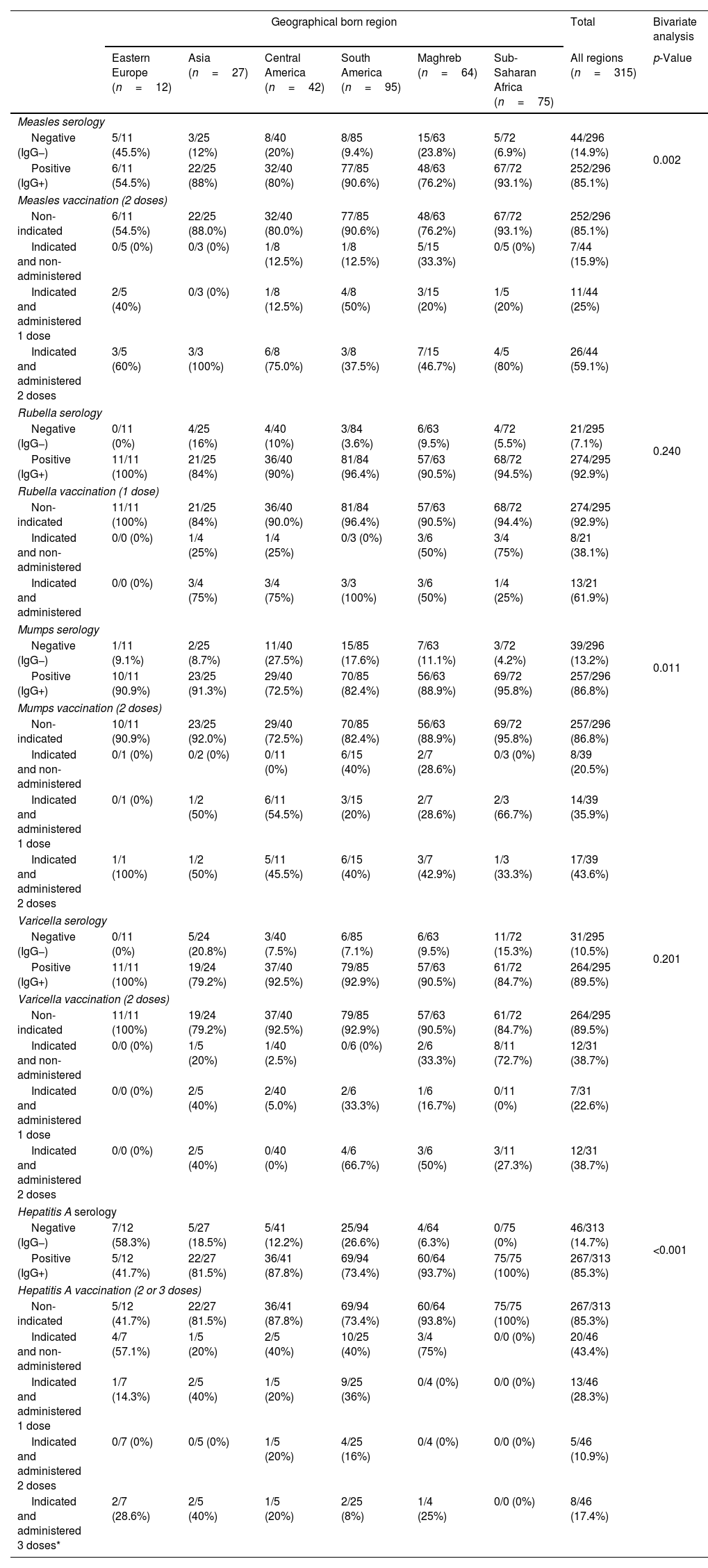

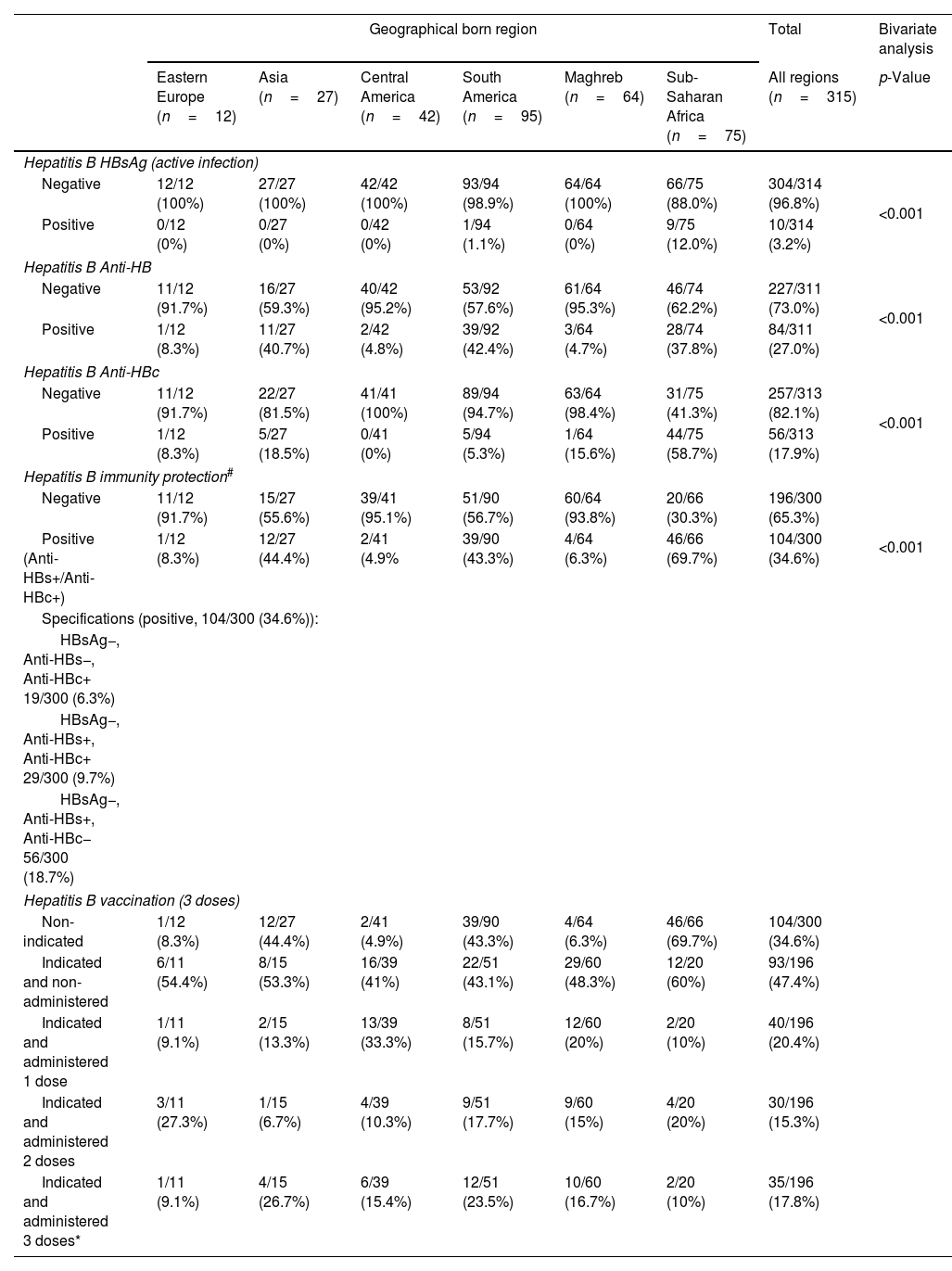

Considering the whole study population, the seroprevalence was 252/296 (85.1%) for measles, 274/295 (92.9%) for rubella, 257/296 (86.8%) for mumps, 264/295 (89.5%) for varicella, and 267/313 (85.3%) for HAV (Table 3). In 104/300 (34.7%) immunity to HBV was observed, either by natural infection (HBsAg−, Anti-HBc+) or by vaccination (Anti-HBc−, Anti-HBs+). A total of 10/314 (3.2%) had an active HBV infection (HBsAg+, Anti-HBs−, Anti-HBc+). Hepatitis B serology results are show in Table 4. Serology and vaccination results were analyzed according to geographical born region of the individuals and represented in Tables 3 and 4. Vaccines indicated and non-administered were due to patient reluctance to be vaccinated or to relocation to other health facility or country, and were particularly relevant for vaccines requiring second or third doses six months after the first vaccination.

Serology/vaccination data table of migrants from Drassanes-Vall d’Hebron Infectious Diseases and International Health Center during 2020–2021 by geographical born region (Asia, Eastern Europe, Central America, South America, Maghreb and Sub-Saharan Africa) and measles, rubella, mumps, varicella and hepatitis A virus.

| Geographical born region | Total | Bivariate analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern Europe (n=12) | Asia (n=27) | Central America (n=42) | South America (n=95) | Maghreb (n=64) | Sub-Saharan Africa (n=75) | All regions (n=315) | p-Value | |

| Measles serology | ||||||||

| Negative (IgG−) | 5/11 (45.5%) | 3/25 (12%) | 8/40 (20%) | 8/85 (9.4%) | 15/63 (23.8%) | 5/72 (6.9%) | 44/296 (14.9%) | 0.002 |

| Positive (IgG+) | 6/11 (54.5%) | 22/25 (88%) | 32/40 (80%) | 77/85 (90.6%) | 48/63 (76.2%) | 67/72 (93.1%) | 252/296 (85.1%) | |

| Measles vaccination (2 doses) | ||||||||

| Non-indicated | 6/11 (54.5%) | 22/25 (88.0%) | 32/40 (80.0%) | 77/85 (90.6%) | 48/63 (76.2%) | 67/72 (93.1%) | 252/296 (85.1%) | |

| Indicated and non-administered | 0/5 (0%) | 0/3 (0%) | 1/8 (12.5%) | 1/8 (12.5%) | 5/15 (33.3%) | 0/5 (0%) | 7/44 (15.9%) | |

| Indicated and administered 1 dose | 2/5 (40%) | 0/3 (0%) | 1/8 (12.5%) | 4/8 (50%) | 3/15 (20%) | 1/5 (20%) | 11/44 (25%) | |

| Indicated and administered 2 doses | 3/5 (60%) | 3/3 (100%) | 6/8 (75.0%) | 3/8 (37.5%) | 7/15 (46.7%) | 4/5 (80%) | 26/44 (59.1%) | |

| Rubella serology | ||||||||

| Negative (IgG−) | 0/11 (0%) | 4/25 (16%) | 4/40 (10%) | 3/84 (3.6%) | 6/63 (9.5%) | 4/72 (5.5%) | 21/295 (7.1%) | 0.240 |

| Positive (IgG+) | 11/11 (100%) | 21/25 (84%) | 36/40 (90%) | 81/84 (96.4%) | 57/63 (90.5%) | 68/72 (94.5%) | 274/295 (92.9%) | |

| Rubella vaccination (1 dose) | ||||||||

| Non-indicated | 11/11 (100%) | 21/25 (84%) | 36/40 (90.0%) | 81/84 (96.4%) | 57/63 (90.5%) | 68/72 (94.4%) | 274/295 (92.9%) | |

| Indicated and non-administered | 0/0 (0%) | 1/4 (25%) | 1/4 (25%) | 0/3 (0%) | 3/6 (50%) | 3/4 (75%) | 8/21 (38.1%) | |

| Indicated and administered | 0/0 (0%) | 3/4 (75%) | 3/4 (75%) | 3/3 (100%) | 3/6 (50%) | 1/4 (25%) | 13/21 (61.9%) | |

| Mumps serology | ||||||||

| Negative (IgG−) | 1/11 (9.1%) | 2/25 (8.7%) | 11/40 (27.5%) | 15/85 (17.6%) | 7/63 (11.1%) | 3/72 (4.2%) | 39/296 (13.2%) | 0.011 |

| Positive (IgG+) | 10/11 (90.9%) | 23/25 (91.3%) | 29/40 (72.5%) | 70/85 (82.4%) | 56/63 (88.9%) | 69/72 (95.8%) | 257/296 (86.8%) | |

| Mumps vaccination (2 doses) | ||||||||

| Non-indicated | 10/11 (90.9%) | 23/25 (92.0%) | 29/40 (72.5%) | 70/85 (82.4%) | 56/63 (88.9%) | 69/72 (95.8%) | 257/296 (86.8%) | |

| Indicated and non-administered | 0/1 (0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 0/11 (0%) | 6/15 (40%) | 2/7 (28.6%) | 0/3 (0%) | 8/39 (20.5%) | |

| Indicated and administered 1 dose | 0/1 (0%) | 1/2 (50%) | 6/11 (54.5%) | 3/15 (20%) | 2/7 (28.6%) | 2/3 (66.7%) | 14/39 (35.9%) | |

| Indicated and administered 2 doses | 1/1 (100%) | 1/2 (50%) | 5/11 (45.5%) | 6/15 (40%) | 3/7 (42.9%) | 1/3 (33.3%) | 17/39 (43.6%) | |

| Varicella serology | ||||||||

| Negative (IgG−) | 0/11 (0%) | 5/24 (20.8%) | 3/40 (7.5%) | 6/85 (7.1%) | 6/63 (9.5%) | 11/72 (15.3%) | 31/295 (10.5%) | 0.201 |

| Positive (IgG+) | 11/11 (100%) | 19/24 (79.2%) | 37/40 (92.5%) | 79/85 (92.9%) | 57/63 (90.5%) | 61/72 (84.7%) | 264/295 (89.5%) | |

| Varicella vaccination (2 doses) | ||||||||

| Non-indicated | 11/11 (100%) | 19/24 (79.2%) | 37/40 (92.5%) | 79/85 (92.9%) | 57/63 (90.5%) | 61/72 (84.7%) | 264/295 (89.5%) | |

| Indicated and non-administered | 0/0 (0%) | 1/5 (20%) | 1/40 (2.5%) | 0/6 (0%) | 2/6 (33.3%) | 8/11 (72.7%) | 12/31 (38.7%) | |

| Indicated and administered 1 dose | 0/0 (0%) | 2/5 (40%) | 2/40 (5.0%) | 2/6 (33.3%) | 1/6 (16.7%) | 0/11 (0%) | 7/31 (22.6%) | |

| Indicated and administered 2 doses | 0/0 (0%) | 2/5 (40%) | 0/40 (0%) | 4/6 (66.7%) | 3/6 (50%) | 3/11 (27.3%) | 12/31 (38.7%) | |

| Hepatitis A serology | ||||||||

| Negative (IgG−) | 7/12 (58.3%) | 5/27 (18.5%) | 5/41 (12.2%) | 25/94 (26.6%) | 4/64 (6.3%) | 0/75 (0%) | 46/313 (14.7%) | <0.001 |

| Positive (IgG+) | 5/12 (41.7%) | 22/27 (81.5%) | 36/41 (87.8%) | 69/94 (73.4%) | 60/64 (93.7%) | 75/75 (100%) | 267/313 (85.3%) | |

| Hepatitis A vaccination (2 or 3 doses) | ||||||||

| Non-indicated | 5/12 (41.7%) | 22/27 (81.5%) | 36/41 (87.8%) | 69/94 (73.4%) | 60/64 (93.8%) | 75/75 (100%) | 267/313 (85.3%) | |

| Indicated and non-administered | 4/7 (57.1%) | 1/5 (20%) | 2/5 (40%) | 10/25 (40%) | 3/4 (75%) | 0/0 (0%) | 20/46 (43.4%) | |

| Indicated and administered 1 dose | 1/7 (14.3%) | 2/5 (40%) | 1/5 (20%) | 9/25 (36%) | 0/4 (0%) | 0/0 (0%) | 13/46 (28.3%) | |

| Indicated and administered 2 doses | 0/7 (0%) | 0/5 (0%) | 1/5 (20%) | 4/25 (16%) | 0/4 (0%) | 0/0 (0%) | 5/46 (10.9%) | |

| Indicated and administered 3 doses* | 2/7 (28.6%) | 2/5 (40%) | 1/5 (20%) | 2/25 (8%) | 1/4 (25%) | 0/0 (0%) | 8/46 (17.4%) | |

IQR: interquartile range; y.o.: years old. Not all patients were serology tested for each studied disease.

Serology/vaccination data table of migrants from Drassanes-Vall d’Hebron Infectious Diseases and International Health Center during 2020–2021 by geographical born region (Asia, Eastern Europe, Central America, South America, Maghreb and Sub-Saharan Africa) and hepatitis B virus.

| Geographical born region | Total | Bivariate analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern Europe (n=12) | Asia (n=27) | Central America (n=42) | South America (n=95) | Maghreb (n=64) | Sub-Saharan Africa (n=75) | All regions (n=315) | p-Value | |

| Hepatitis B HBsAg (active infection) | ||||||||

| Negative | 12/12 (100%) | 27/27 (100%) | 42/42 (100%) | 93/94 (98.9%) | 64/64 (100%) | 66/75 (88.0%) | 304/314 (96.8%) | <0.001 |

| Positive | 0/12 (0%) | 0/27 (0%) | 0/42 (0%) | 1/94 (1.1%) | 0/64 (0%) | 9/75 (12.0%) | 10/314 (3.2%) | |

| Hepatitis B Anti-HB | ||||||||

| Negative | 11/12 (91.7%) | 16/27 (59.3%) | 40/42 (95.2%) | 53/92 (57.6%) | 61/64 (95.3%) | 46/74 (62.2%) | 227/311 (73.0%) | <0.001 |

| Positive | 1/12 (8.3%) | 11/27 (40.7%) | 2/42 (4.8%) | 39/92 (42.4%) | 3/64 (4.7%) | 28/74 (37.8%) | 84/311 (27.0%) | |

| Hepatitis B Anti-HBc | ||||||||

| Negative | 11/12 (91.7%) | 22/27 (81.5%) | 41/41 (100%) | 89/94 (94.7%) | 63/64 (98.4%) | 31/75 (41.3%) | 257/313 (82.1%) | <0.001 |

| Positive | 1/12 (8.3%) | 5/27 (18.5%) | 0/41 (0%) | 5/94 (5.3%) | 1/64 (15.6%) | 44/75 (58.7%) | 56/313 (17.9%) | |

| Hepatitis B immunity protection# | ||||||||

| Negative | 11/12 (91.7%) | 15/27 (55.6%) | 39/41 (95.1%) | 51/90 (56.7%) | 60/64 (93.8%) | 20/66 (30.3%) | 196/300 (65.3%) | <0.001 |

| Positive (Anti-HBs+/Anti-HBc+) | 1/12 (8.3%) | 12/27 (44.4%) | 2/41 (4.9% | 39/90 (43.3%) | 4/64 (6.3%) | 46/66 (69.7%) | 104/300 (34.6%) | |

| Specifications (positive, 104/300 (34.6%)): | ||||||||

| HBsAg−, Anti-HBs−, Anti-HBc+ 19/300 (6.3%) | ||||||||

| HBsAg−, Anti-HBs+, Anti-HBc+ 29/300 (9.7%) | ||||||||

| HBsAg−, Anti-HBs+, Anti-HBc− 56/300 (18.7%) | ||||||||

| Hepatitis B vaccination (3 doses) | ||||||||

| Non-indicated | 1/12 (8.3%) | 12/27 (44.4%) | 2/41 (4.9%) | 39/90 (43.3%) | 4/64 (6.3%) | 46/66 (69.7%) | 104/300 (34.6%) | |

| Indicated and non-administered | 6/11 (54.4%) | 8/15 (53.3%) | 16/39 (41%) | 22/51 (43.1%) | 29/60 (48.3%) | 12/20 (60%) | 93/196 (47.4%) | |

| Indicated and administered 1 dose | 1/11 (9.1%) | 2/15 (13.3%) | 13/39 (33.3%) | 8/51 (15.7%) | 12/60 (20%) | 2/20 (10%) | 40/196 (20.4%) | |

| Indicated and administered 2 doses | 3/11 (27.3%) | 1/15 (6.7%) | 4/39 (10.3%) | 9/51 (17.7%) | 9/60 (15%) | 4/20 (20%) | 30/196 (15.3%) | |

| Indicated and administered 3 doses* | 1/11 (9.1%) | 4/15 (26.7%) | 6/39 (15.4%) | 12/51 (23.5%) | 10/60 (16.7%) | 2/20 (10%) | 35/196 (17.8%) | |

HBsAg: hepatitis B surface antigen; Anti-HBs: hepatitis B surface antibody; Anti-HBc: hepatitis B core antibody. Negative hepatitis B exposure was considered as a negative result for HBsAg, Anti-HBs and Anti-HBc serology. IQR: interquartile range; y.o.: years old.

Measles seropositivity was 79/95 (83.1%) amongst females and 173/201 (86.0%) amongst males, showing non-significant statistical differences (p>0.05). Significant statistical differences (p<0.05) in measles positive serology results were observed based on the area of origin: Eastern Europe (54.5%) versus South America (90.6%) and Sub-Saharan Africa (93.1%).

MumpsMumps seropositivity was 77/95 (81.0%) amongst females and 180/201 (89.6%) amongst males, showing non-significant statistical differences (p>0.05). In addition, differences (p<0.01) in mumps positive serology results were observed based on the area of origin: Sub-Saharan Africa (95.8%) versus Central America (72.5%).

Rubella and varicellaRubella and varicella seropositivity were 86/95 (90.5%) and 89/95 (93.7%) amongst females respectively; and 188/200 (94.0%) and 175/200 (87.5%) amongst males respectively, showing non-significant statistical differences in both cases (p>0.05). Differences in rubella and varicella serology results based on the area of origin were not observed.

Hepatitis AHAV seropositivity was 93/102 (91.2%) amongst females and 208/212 (98.1%) amongst males, describing non-significant statistical differences (p>0.05). Moreover, differences (p<0.05) in HAV positive serology results were observed based on the area of origin: South America (73.4%) versus Central America (87.8%), Maghreb (93.7%) and Sub-Saharan Africa (100%).

Hepatitis BHBV seropositivity was 33/100 (33.0%) amongst females and 81/210 (38.6%) amongst males, showing non-significant statistical differences (p>0.05). There were statistical significant differences (p<0.001) between HBV positive serology in Sub-Saharan Africa (73.3%) compared to all other analyzed regions. Prevalence of HBV active infections in Sub-Saharan African individuals of our study was significantly high, 9/75 (12%), in comparison with other regions.

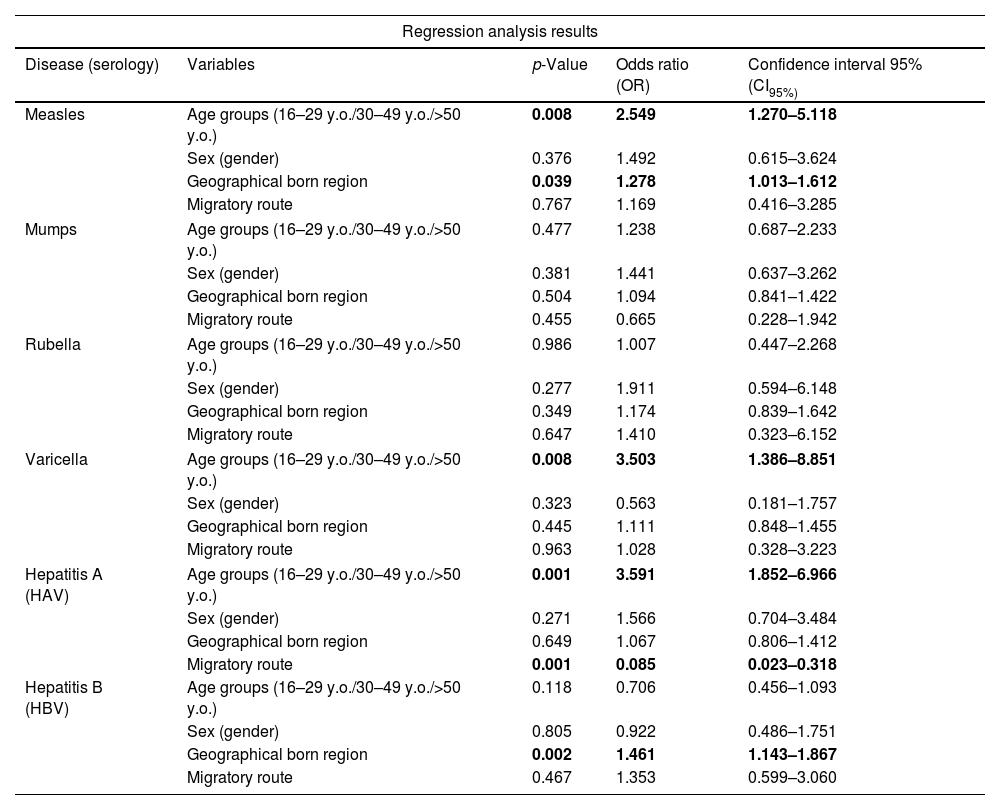

Logistic regression shows that the established age groups (16–29 y.o., 30–50 y.o. and >50 y.o.) were statistically correlated with measles [CI95%=1.27, 5.11; odds ratio (OR) 2.54] and varicella (CI95%=1.38, 8.85; OR 3.50) positive serology results, associated with a higher rate of positive results in adults >50 years old. Hepatitis A serology also shows a statistical correlation with the established age groups, associated with a higher positivity rate in older individuals [CI95%=1.85, 6.96; OR 3.59]. We observed that geographical born region, concretely Sub-Saharan Africa, was statistically correlated with measles (CI95%=1.01, 1.61; OR 1.28) and HBV (CI95%=1.14, 1.86; OR 1.46) positive serology results. Logistic regression shows non-statistical correlation between rubella and mumps positive serology results and; gender, age, geographical born region, time elapsed between arrival to Spain, and migratory route. In detail regression analysis results are shown in Table 6.

Seroprevalence screening of migrants from Vall d’Hebron-Drassanes Tropical Medicine and International Health Unit (2020–2021).

| Seroprevalence analysis of patients screened at the Vall d’Hebron-Drassanes Tropical Medicine and International Health Unit (2020–2021) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upon arrival screening | Vaccination campaign | ||||

| Disease | Immunity at arrival | Patients with non-immunity protection | Vaccinated patients (all doses) | Total immunity protection | Considering patients with incomplete vaccination schedules (at least one dose) |

| Measles | 252/296 (85.1%) | 44/296 (14.9%) | 26/44 (59.1%) | 278/296 (93.9%) | 289/296 (97.6%) |

| Rubella | 274/295 (92.9%) | 21/295 (7.1%) | 13/21 (61.9%) | 287/295 (97.3%) | 287/295 (97.3%) |

| Mumps | 257/296 (86.8%) | 39/296 (13.1%) | 17/39 (43.6%) | 274/296 (92.6%) | 288/296 (97.3%) |

| Varicella | 264/295 (89.5%) | 31/295 (10.5%) | 12/31 (38.7%) | 276/295 (93.6%) | 283/295 (95.9%) |

| Hepatitis A | 267/313 (85.3%) | 46/313 (14.3%) | 13/46 (28.3%) | 280/313 (89.5%) | 293/313 (93.6%) |

| Hepatitis B* | 104/300 (34.6%) | 196/300 (65.3%) | 35/196 (17.8%) | 139/300 (46.3%) | 209/300 (69.7%) |

Patients vaccinated with the full schedule are considered to have immunity.

Regression analysis for risk factors associated with positive serology results of measles, mumps, rubella, varicella, HAV and HBV.

| Regression analysis results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease (serology) | Variables | p-Value | Odds ratio (OR) | Confidence interval 95% (CI95%) |

| Measles | Age groups (16–29 y.o./30–49 y.o./>50 y.o.) | 0.008 | 2.549 | 1.270–5.118 |

| Sex (gender) | 0.376 | 1.492 | 0.615–3.624 | |

| Geographical born region | 0.039 | 1.278 | 1.013–1.612 | |

| Migratory route | 0.767 | 1.169 | 0.416–3.285 | |

| Mumps | Age groups (16–29 y.o./30–49 y.o./>50 y.o.) | 0.477 | 1.238 | 0.687–2.233 |

| Sex (gender) | 0.381 | 1.441 | 0.637–3.262 | |

| Geographical born region | 0.504 | 1.094 | 0.841–1.422 | |

| Migratory route | 0.455 | 0.665 | 0.228–1.942 | |

| Rubella | Age groups (16–29 y.o./30–49 y.o./>50 y.o.) | 0.986 | 1.007 | 0.447–2.268 |

| Sex (gender) | 0.277 | 1.911 | 0.594–6.148 | |

| Geographical born region | 0.349 | 1.174 | 0.839–1.642 | |

| Migratory route | 0.647 | 1.410 | 0.323–6.152 | |

| Varicella | Age groups (16–29 y.o./30–49 y.o./>50 y.o.) | 0.008 | 3.503 | 1.386–8.851 |

| Sex (gender) | 0.323 | 0.563 | 0.181–1.757 | |

| Geographical born region | 0.445 | 1.111 | 0.848–1.455 | |

| Migratory route | 0.963 | 1.028 | 0.328–3.223 | |

| Hepatitis A (HAV) | Age groups (16–29 y.o./30–49 y.o./>50 y.o.) | 0.001 | 3.591 | 1.852–6.966 |

| Sex (gender) | 0.271 | 1.566 | 0.704–3.484 | |

| Geographical born region | 0.649 | 1.067 | 0.806–1.412 | |

| Migratory route | 0.001 | 0.085 | 0.023–0.318 | |

| Hepatitis B (HBV) | Age groups (16–29 y.o./30–49 y.o./>50 y.o.) | 0.118 | 0.706 | 0.456–1.093 |

| Sex (gender) | 0.805 | 0.922 | 0.486–1.751 | |

| Geographical born region | 0.002 | 1.461 | 1.143–1.867 | |

| Migratory route | 0.467 | 1.353 | 0.599–3.060 | |

Bold text indicates statistical significance. y.o.: years old.

The completion rates for indicated vaccines were as follows 26/44 (59.1%) for measles (2 doses); 13/21 (61.9%) for rubella (1 dose); 17/39 (43.6%) for mumps (2 doses); 12/31 (38.7%) for varicella (2 doses), 13/46 (28.3%) for HAV (2/3 doses); and 35/196 (17.8%) for HBV (3 doses). Therefore, the final immunity protection after the visit at the Unit was 93.9% for measles, 97.3% for rubella, 92.6% for mumps, 93.6% for varicella, 89.5% for HAV, and 46.3% for HBV (Table 5). There were non-statistical significant differences in terms of vaccination uptake depending on the geographical born region.

DiscussionMigrants visited at the IHCDVH were mostly young adult males from the American continent 45.5%, Sub-Saharan Africa 23.8%, and the Maghreb 20.3%; areas from which most immigrants in Catalonia come from.17 The most represented country was Venezuela 18.1%, probably due to the political-economic conflict in this region during the years of the study.18 It was followed by Algeria 14%, Colombia 9.5%, Mali 8.3%, El Salvador 6% and Morocco 5.4%, in concordance with the Catalan Institute of Statistics (CIS) about non-EU27 populations in Catalonia.17 Migration route showed a high percentage of land-maritime journeys from Sub-Saharan Africa and Maghreb regions with 98.6% and 91.5% of individuals respectively. Data is in concordance with European Council in which migration routes from Morocco to the Iberian Peninsula and Wester Africa to Canary Islands represent the vast majority of irregular land-maritime migration movements to Spain.19 However, other routes or means of transport are used by non-irregular migratory movements. Considering language barriers (40.6% do not speak Spanish/Catalan) was crucial to culturally adapt the health consultation procedure and ensure correct understanding of the indications.20 Health workers should develop specific skills for the care of migrants, in order to face the language, cultural and medical barriers.21

Migrant screening protocols are crucial to describe the prevalence of infectious diseases, with remarkable positive results for these populations.22,23 Our seroprevalence screening showed immunization coverage at arrival to the health center in 92.9% for rubella, 89.5% for varicella, 86.8% for mumps, 85.3% for HAV and 85.1% for measles showing in all cases a >85%. In detail, measles (85.1%), mumps (86.8%) and rubella (92.9%) immunization data at arrival were higher in comparison with other similar studies (83.7% for measles, 67.1% for mumps and 85.6% for rubella).6 Varicella seroprevalences at arrival (89.5%) were in concordance with other studies, and below the immunity rates of host populations.24,25 HAV seroprevalence results at arrival (85.3%) were close to others described in similar studies, with the same interpretation if compared by geographical born region.26,27 These differences could be explained in terms of cases and incidence in origin countries, or rarely due to vaccination during migration routes.28 Hepatitis B screening showed relatively low coverage results (34.6%) in comparison with the other analyzed VPD. However, HBV immunity results were in concordance with other meta-analysis studies in migrants and refugees (39.7%), reaffirming a general concern regarding this infection.29 Some reasons to explain the low immunity rates of HBV at arrival could be the multiple vaccine doses required for immunization, the time gaps between doses, the absence of the disease vaccine recommendation in national vaccination schedules, the low resources of the birth and origin country, and non-responders to HBV vaccine.30 The results of seropositivity disaggregated by sex did not show statistical significant differences for any of VPD, although males in our cohort population have higher percentages of seropositivity than females for measles, mumps, rubella, HAV and HBV. Vaccination inequities in low and middle income countries due to socioeconomic, educational or maternity reasons could explain those gender-based differences.31 Migration routes from Sub-Saharan Africa region to South Europe Mediterranean countries encompasses areas where some of the diseases studied are endemic, thus enhancing infection during the migratory route.25 Similar studies with unaccompanied minor migrant populations in the same center show that immunization status against rubella (94%), varicella (94%), hepatitis A (91%), varicella (83%), measles (80%) and hepatitis B (36%, HBsAb+) were closely in concordance with our adult studied population results.32 The low immunization ratio of the population for HBV prior to arrival at the center was similar in both studies, showing outstanding results due to insufficient coverage, or that HBV antibodies decrease over time as previously reported.33

Age-linked seropositivity results for measles, varicella and hepatitis A show that older individuals (≥50 y.o.) have higher percentages of immunity compared to younger populations (16–29 y.o.). This could be explained by the lower vaccination rates in their countries of origin and the higher probability of infection during the life course of older individuals, thus explaining the differences in immunity. Data bias cannot be ruled out due to the niched nature of the analyzed group.

After vaccination, the immunity protection of the study population was 93.9% for measles, 97.3% for rubella, 92.6% for mumps, 93.6% for varicella, 89.5% for HAV, and 46.3% for HBV. These data may be underestimated, as occasionally patients could complete the vaccination schedule in other health centers, Spanish autonomous communities or countries. Measles (93.9%) and mumps (92.6%) immunity after vaccination intervention were midway the herd immunity thresholds (HIT) (93–95% for measles and 88–93% for mumps), showing a considerable increase in terms of community herd immunity.6 In the case of rubella (97.3%) immunity rates reached after vaccination were above HIT (83–94%), confirming a satisfactory immunization intervention.6 Varicella data shows 93.6% immunity after vaccination, closely below HIT 2025 Spanish immunization objectives.24 Analyzing the vaccination uptake data in patients without immunity, we obtained the highest rate for rubella (61.9%), followed by measles (59.1%) and mumps (43.6%). Rubella only requires one dose, and therefore it is not necessary for the patient to return to the center to complete the vaccination schedule. This factor may explain the higher uptake of vaccination for this disease compared to the others. In the case of measles and mumps, we also observed a high percentage of acceptance of vaccination due to the availability of the MMR vaccine in a single formulation. Vaccination strategies are optimal and allow to increase vaccination rates in the study population, however logistical barriers related to the social-health system do not sufficiently assist vulnerable populations to return to vaccination centers and administer the subsequent doses.34 Relevant studies purpose several strategies based on language and literacy improvements, awareness and knowledge for health workers and migrants to increase vaccination uptake.35

As a limitation, our study population is a selected sample of migrants referred by shelter centers, and are not representative of all migrant population in Catalonia. However, this type of institutional collaboration allows to speed up the arrival to the health service. The retrospective nature of the study can also be considered a limitation, as some data could be missing. The disparity in results by country of origin indicates that our data are representative of a selected sample of a country/region population, but cannot be generalized to all migrant population. In addition, the low number of patients from Eastern Europe (n=12) suggests that the results may not be representative for this group. The interval (6 months) between the 2nd and 3rd HBV doses was a limiting factor when measuring immunity percentages, due to the high mobility of the populations studied and the lack of vaccination data when leaving our autonomous community or country. Finally, it should be noted that the years of the study (2020–2021) were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, in which most countries implemented restrictive mobility measures and migratory movements were considerably reduced, affecting the number of migrants attended in our center.36

In summary, the vaccination intervention has increased immunity rates for measles, mumps, rubella, varicella, HAV and HBV, in the migrant population studied. This type of interventions, that already demonstrated its cost-effectiveness,37 can help to have more information on seroprevalence in migrants, own to vaccination or natural immunity, depending on their geographical region of origin.

FundingThis research has not received specific support from public sector agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit organizations.

Ethical approval and patient consentThe study protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the Vall d’Hebron University Hospital (Barcelona, Spain) (PR(AG)546/2021). Procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2013. A referral agreement was made between the shelters and the UIHDV for all migrants. Oral informed consent was obtained from all the patients before the performance of any test, and data was anonymized and protected.

Conflict of interestAuthors declare there are non-conflict of interest.