In Spain, half of new HIV diagnoses are late and a significant proportion of people living with HIV have not yet been diagnosed. Our aim was to evaluate the effectiveness of an automated opportunistic HIV screening strategy in the hospital setting.

MethodsBetween April 2022 and September 2023, HIV testing was performed on all patients in whom a hospital admission analytical profile, a pre-surgical profile and several pre-designed serological profiles (fever of unknown origin, pneumonia, mononucleosis, hepatitis, infection of sexual transmission, rash, endocarditis and myopericarditis) was requested. A circuit was started to refer patients the specialists.

Results6407 HIV tests included in the profiles were performed and 18 (0.3%) new cases were diagnosed (26.4% of diagnoses in the health area). Five patients were diagnosed by hospital admission and pre-surgery profile and 13 by a serological profile requested for indicator entities (fever of unknown origin, sexually transmitted infection, mononucleosis) or possibly associated (pneumonia) with HIV occult infection. Recent infection was documented in 5 (27.8%) patients and late diagnosis in 9 (50.0%), of whom 5 (55.5%) had previously missed the opportunity to be diagnosed.

ConclusionsThis opportunistic screening was profitable since the positive rate of 0.3% is cost-effective and allowed a quarter of new diagnoses to be made, so it seems a good strategy that contributes to reducing hidden infection and late diagnosis.

En España, la mitad de los nuevos diagnósticos del virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana (VIH) son tardíos y una proporción significativa de las personas que viven con el VIH (PVVIH) aún no se ha diagnosticado. Nuestro objetivo fue evaluar la efectividad de una estrategia de cribado oportunista automatizado del VIH en el entorno hospitalario.

MétodosEntre abril de 2022 y septiembre de 2023, se realizó la prueba del VIH a todos los pacientes en que se solicitó un perfil analítico de ingreso hospitalario, un perfil prequirúrgico y en varios perfiles serológicos prediseñados (fiebre de origen desconocido, neumonía, mononucleosis, hepatitis, infección de transmisión sexual, exantema, endocarditis y miopericarditis). Se estableció un circuito de derivación de pacientes diagnosticados al especialista.

ResultadosSe realizaron 6.407 pruebas de VIH incluidas en los perfiles y se diagnosticaron 18 (0,3%) nuevos casos (26,4% de todos los diagnósticos del área sanitaria). Cinco pacientes se diagnosticaron por perfil de ingreso hospitalario o prequirúrgico y 13 por un perfil serológico solicitado por entidades indicadoras (fiebre de origen desconocido, infección de transmisión sexual, mononucleosis) o posiblemente asociadas (neumonía) a infección oculta. En cinco (27,8%) pacientes se documentó una infección reciente y en nueve (50,0%) un diagnóstico tardío, de los que en cinco (55,5%) se había perdido la oportunidad de ser diagnosticados previamente.

ConclusionesEste cribado oportunista fue rentable ya que la tasa de positivos del 0,3% es coste-efectiva y permitió realizar la cuarta parte de los nuevos diagnósticos, por lo que parece una buena estrategia que contribuye a disminuir la infección oculta y el diagnóstico tardío.

In Spain, as in most western European countries, half of new human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection diagnoses are late and, in recent years, this percentage has remained stable. In addition, it is estimated that a significant proportion of people living with HIV (PLHIV) are unaware of their status (undiagnosed infection).1 Late diagnosis is associated with increased morbidity and mortality and promotes the spread of infection, as the virus is mainly transmitted by people who do not know they are infected and therefore do not receive antiretroviral therapy.2,3

Structural obstacles, such as lack of awareness of situations indicative of or possibly associated with a higher prevalence of undiagnosed HIV infection4 by physicians not routinely involved in the care of PLHIV, and work overload,5 have been identified as possible barriers to diagnosis. It is also known that there are individual reasons why some people refuse testing when offered for fear of stigma or low perceived risk of HIV infection.6

In our area, in a study conducted in patients diagnosed late between 2015 and 2021, it was found that more than 40% had had the chance to be diagnosed in the hospital setting in the previous three years, half of these cases having presented with clinical manifestations in which HIV testing was recommended.7 In this study, older people, people born outside Spain and women were more likely to have missed opportunities. Therefore, the design of facilitating screening strategies for known HIV indicators could help to reduce undiagnosed infection.8

Because HIV testing is the first step in reducing undiagnosed infection and late diagnosis and thus achieving the UNAIDS goal of ending the HIV epidemic by 2030,9 a non-urgent opportunistic screening strategy was designed for patients attending specialised care (hospitalisation and outpatient clinics) in our health area. This consists of incorporating the diagnostic test into a series of automated blood test profiles, with inclusion of the test specified in the name of the profile. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of this automated opportunistic HIV screening strategy 18 months after its implementation.

Patients and methodsBetween 1 April 2022 and 30 September 2023, HIV testing was performed on all patients who attended the hospital, both at the Hospital’s Accident and Emergency Department (A&E) and on those who were hospitalised or attended specialised care consultations and for whom a hospital admission complete blood count was requested, on those who underwent a pre-surgical protocol and on patients in whom different pre-designed serological profiles were requested (fever of unknown origin, pneumonia, infectious mononucleosis, acute/chronic hepatitis, sexually transmitted infection, exanthema, herpes-zoster, endocarditis and myopericarditis), in a health area with an assigned population of approximately 350,000 people over 14 years of age. Test inclusion was automated and the name of the profile specified that HIV testing was included so that the doctor could ask the patient for consent. Our laboratory’s request comprises two blood test profiles for hospital admission and pre-surgery that include and specify the HIV test, and two others that do not include it, so that the doctor treating the patient can request it at his or her discretion. The test was performed within 24 working hours of extraction. Positive results were reported by the microbiologist by telephone call to both the requesting physician and the infectious disease specialist. A referral circuit was established for patients to the Infectious Diseases Unit so that the specialists who usually care for PLHIV would be responsible for reporting the test result and implementing the usual patient management protocols.

When analysing the results, the patient was considered to have acute or primary HIV infection when diagnosed in the time period between the moment of infection and the appearance of antibodies (seroconversion), and recent infection when a negative test was available in the six months prior to diagnosis. Diagnosis was considered late when, having ruled out acute infection, the CD4 lymphocyte count was below 350 cells/μl. Patients with late diagnosis were checked for any missed opportunities to be diagnosed in the hospital setting in the previous three years.

For the statistical analysis of the results, qualitative variables are expressed in terms of number and percentage, and quantitative variables in terms of mean and standard deviation.

The study was approved by the hospital’s Independent Ethics Committee (IEC: 2023-50-1).

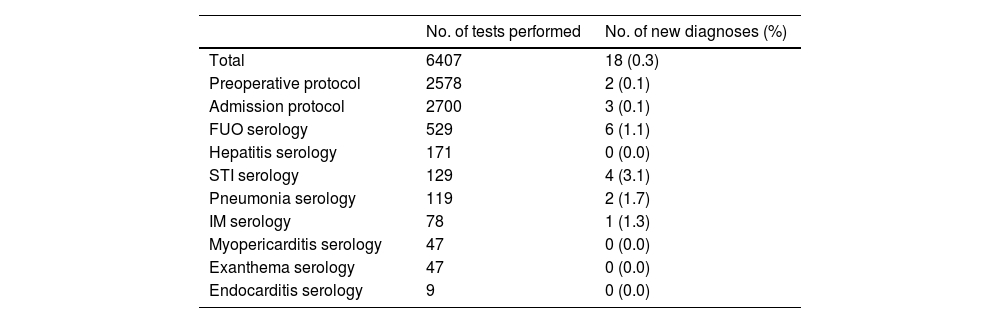

ResultsDuring the study period, 68 patients were diagnosed with HIV infection in our health area, 35 (51.5%) in the primary care setting and 33 (48.5%) in specialised care (15 in A&E, six in hospitalised patients and 12 in specialist outpatient clinics). Based on opportunistic screening by pre-designed blood test profiles, 6407 HIV serologies were requested (accounting for 30.2% of the 21,189 tests requested in that period in the hospital setting) and 18 (0.3%) new cases were diagnosed. These 18 patients accounted for 26.5% of all new diagnoses in this period and 54.5% of diagnoses made in the hospital setting. Table 1 shows the number of screening tests performed in each profile and the number of people diagnosed. Three patients were diagnosed when a hospital admission blood test profile was ordered (in all three cases the discharge diagnosis was Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia) and two in the pre-surgical protocol profile (in one case for bilateral inguinal hernia surgery and in another for orbital pseudotumor surgery). The remaining 13 patients were diagnosed by a serological profile encompassing signs or symptoms indicative of or possibly associated with undiagnosed HIV infection.

Number of HIV screening tests performed in a pre-designed profile and number of people diagnosed.

| No. of tests performed | No. of new diagnoses (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 6407 | 18 (0.3) |

| Preoperative protocol | 2578 | 2 (0.1) |

| Admission protocol | 2700 | 3 (0.1) |

| FUO serology | 529 | 6 (1.1) |

| Hepatitis serology | 171 | 0 (0.0) |

| STI serology | 129 | 4 (3.1) |

| Pneumonia serology | 119 | 2 (1.7) |

| IM serology | 78 | 1 (1.3) |

| Myopericarditis serology | 47 | 0 (0.0) |

| Exanthema serology | 47 | 0 (0.0) |

| Endocarditis serology | 9 | 0 (0.0) |

FUO: fever of unknown origin; IM: infectious mononucleosis; STI: sexually transmitted infection.

Of the 18 patients, 14 (77.8%) were male, the mean age was 46.3&#¿;±&#¿;12.9 (range: 22–74) years and four (22.2%) were born outside Spain. In all cases, sexual intercourse was the likely route of transmission. Five patients (27.8%) were documented to have an acute or recent infection and nine (50.0%) had a late diagnosis, of whom seven (77.8%) had <200 CD4 lymphocytes/μl. Of the nine patients with late diagnosis, eight (88.9%) were male, the mean age was 51.8&#¿;±&#¿;12.5 years and two (22.2%) were born outside Spain. Five of them (55.5%) had at least 12 missed opportunities to be diagnosed in the hospital setting in the previous three years, before implementation of this automated opportunistic screening. In terms of diagnosis, 66.7% were made in A&E, with 80% of these deriving from the opportunistic screening profile.

All patients, except two who died and one who refused care, are on antiretroviral therapy. The mean time between diagnosis and first specialist visit was 4.3&#¿;±&#¿;5.4 (range 0–25) days. Of the patients diagnosed, 76.5% were assessed within five days of diagnosis.

DiscussionThe implementation of automated opportunistic screening strategies seems essential to reduce undiagnosed HIV infection, which is a serious problem for the patient and a major contributor to transmission. The fact that medical departments that could diagnose the infection do not order the test means that people with HIV infection who are unaware of their HIV status miss the opportunity to be diagnosed or are diagnosed late. In our setting, where treatment coverage rates of the infection are high,10 being aware of the diagnosis is essential, as it reduces the complications of HIV infection and helps prevent new cases in the population. In addition, establishing referral circuits for those diagnosed to specialist doctors facilitates their pathway to care in an appropriate way and prevents loss to follow-up.

In our study, the automated opportunistic screening strategy comprising the incorporation of HIV testing into a series of blood test profiles, which are ordered in some cases due to the manifestation of clinical signs or symptoms in which the prevalence of undiagnosed infection is estimated to exceed 0.1% (prevalence above which screening is considered cost-effective),11,12 has indeed proved cost-effective, as the positivity rate was three times higher. In addition, more than a quarter of all new cases diagnosed in the study period derived from automated request profiles.

Most of the diagnoses were made by ordering blood test profiles when confronted with signs or symptoms indicative of and associated with undiagnosed HIV infection, clinical scenarios where good medical practice requires that HIV infection be ruled out. In a study conducted in our setting, half of the patients with late diagnosis had had the opportunity to be diagnosed earlier because they presented with indicators associated with undiagnosed HIV infection, and another half because routine testing was offered.7 In our series, in the profiles of sexually transmitted infection, community-acquired pneumonia, infectious mononucleosis and fever of unknown origin, the percentage of positives exceeded 1%. Following the guidelines set by the Spanish Ministry to encourage testing in the healthcare setting, in order to reduce undiagnosed infection, our strategy was able to diagnose up to five patients by routine screening in the hospital admission and pre-surgical protocol blood test profiles. Screening in these profiles was particularly successful, as the percentage of new diagnoses was 0.1%, making it cost-effective.13 However, this strategy is dynamic and subject to change when deemed necessary. Routine testing not only helps to reduce undiagnosed infection, but also in many cases facilitates management of the patient’s presenting complaint. In the three cases in which screening was ordered because of the hospital admission profile, the diagnosis of HIV infection facilitated management of the condition that led to admission, since in all three cases the final diagnosis was P. jirovecii pneumonia, an AIDS-defining opportunistic disease, which had not been ruled out initially. Routine testing (not only in people with risk behaviour) also improves patient acceptance and helps to reduce stigma, as has been shown in some studies.6

Older age, sex and being born outside Spain have been indicated as risk characteristics for late diagnosis in the western world.14,15 With regard to the characteristics of our patients, it is striking that the average age is over 45 years, and over 50 years in patients with late diagnosis, many of whom had previously visited healthcare facilities with HIV-indicative signs or symptoms and had missed the opportunity to be diagnosed.

Routine screening for infection in A&E has been recommended as it is known to be more prevalent than in other medical departments and is cost-effective.16,17 However, its implementation is challenging and not universal. Our strategy has been particularly useful in the A&E department and, in our study, was responsible for 80% of all new cases diagnosed in this department in the study period analysed.

We therefore believe that automation can facilitate universal testing, incorporating it not only in these blood test profiles, but also when blood is collected for any purpose or even when tests are ordered that do not necessarily require a blood sample to be taken. Universal testing facilitates normalisation and acceptance by patients and helps reduce the stigma associated with HIV testing. In our hospital, this strategy is accompanied by regular courses and training sessions for residents, emergency physicians and specialists who are not usually involved in managing this infection.

The results of our study lead to the conclusion that an automated opportunistic diagnostic strategy, together with a patient referral circuit to a specialist, such as the one proposed here, helps to reduce undiagnosed infection. However, to ensure that the first UNAIDS 95 target (to diagnose at least 95% of PLHIV)9 is met, we believe that new strategies must be designed to mitigate the existing difficulties in diagnosing people with undiagnosed HIV infection who attend the different levels of health care, not only in specialised care but also in primary care.18 In addition, a concerted effort is needed, including education campaigns, improvements in access to testing such as universal screening or outreach to vulnerable populations, and updated continuing education for physicians not routinely involved in the care of HIV-positive patients.

FundingThis study received no specific funding from public, private or non-profit organisations.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank José Antonio Alcaide and the entire Patient Access to Care team at Gilead Sciences for their non-monetary logistical support of the study.