Our aim was to describe the epidemiology of acute mastoiditis (AM) in a pediatric population according to the implementation of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV).

MethodsRetrospective, observational study including children diagnosed with AM between January 2000 and December 2019 at a tertiary hospital in Madrid (Spain). The study was grouped into four 5-year periods (2000–2004, 2005–2009, 2010–2014, 2015–2019). The percentage change in the incidence rate was estimated to characterize trends.

ResultsTwo hundred nineteen episodes from 209 patients were included. The incidence rate of AM remained stable during the study period, with an average of 2.2 cases/10,000 emergency department visits/year. There was a significant decrease in the prevalence of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Streptococcus pyogenes was the main microorganism isolated in the last study period.

ConclusionsThe incidence of AM remained stable, although the prevalence of S. pneumoniae decreased in the post-PCV era, being S. pyogenes the main microorganism isolated after the implementation of PCV13.

Nuestro objetivo fue describir la epidemiología de la mastoiditis aguda en una población pediátrica de acuerdo con la implementación de las vacunas antineumocócicas conjugadas.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo, observacional que incluyó a niños diagnosticados con mastoiditis aguda entre enero de 2000 y diciembre de 2019 en un hospital terciario en Madrid (España). El estudio se agrupó en cuatro períodos de 5años (2000-2004, 2005-2009, 2010-2014, 2015-2019). Se estimó el cambio porcentual en la tasa de incidencia para caracterizar las tendencias.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 219 episodios en 209 pacientes. La tasa de incidencia de la mastoiditis aguda se mantuvo estable durante el período del estudio, con un promedio de 2,2 casos por cada 10.000 atenciones en urgencias al año. Hubo una disminución significativa en la prevalencia de S. pneumoniae. S. pyogenes fue el principal microorganismo aislado en el último período del estudio.

ConclusionesLa incidencia de la mastoiditis aguda se mantuvo estable, aunque la prevalencia de S. pneumoniae disminuyó en la era posterior a la vacuna conjugada neumocócica, siendo S. pyogenes el principal microorganismo aislado después de la implementación de la vacunación antineumocócica conjugada 13V.

Acute mastoiditis (AM) is a serious bacterial infection of the mastoid bone, being the most severe complication of acute otitis media.1,2 Although this infection decreased during the post-antibiotic era, it remains a worrisome disease since it mostly affects young children and can develop serious complications.2

Although pneumococcalconjugated vaccine (PCV) have proven to decrease invasive pneumococcal infections,3,4 the impact on AM is not well established. Some investigators have reported a decrease in AM after PCV introduction1 but in other studies this trend has not been confirmed.4,5 Other bacteria, such as Streptococcus pyogenes7 and Fusobacterium necrophorum,8 are emerging as important causes of AM.

In the Community of Madrid (Spain), PCV7 was implemented in the Regional Immunization Program (RIP) in October 2006. In June 2010, it was replaced by PCV13, and from 2012 to 2014 it was excluded from the RIP, being only available for private purchase. Finally, it was reintroduced in January 2015 and has remained in place ever since. In May 2024, PCV13V was replaced by PCV15V in the RIP9 but the study period did not include coverage with this vaccine.

The aim of our study was to describe the epidemiology of AM over a 20-year period (2000–2019) in the pediatric population attended in a tertiary hospital and to evaluate changes in the etiology according to the implementation of the PCV.

Materials and methodsA retrospective, observational study was performed at the Gregorio Marañón University Hospital, a tertiary hospital in Madrid (Spain) with a median of 3420 yearly hospitalizations during 2000–2019. The study population included children <16 years diagnosed with AM between January 2000 and December 2019.

Episodes of AM were identified by searching the hospital admission system for the codes of acute mastoiditis (H70.0) and mastoiditis (H70.9) according to the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision. Charts were reviewed considering the diagnosis of AM based on clinical criteria, including postauricular tenderness, erythema or swelling, or protrusion of the auricle, and radiological findings. Demographics, clinical and microbiological variables were systematically collected from the electronic medical chart.

Microbiological samples (blood cultures, external ear samples in children with ear discharge, middle ear aspirates, and surgically obtained samples) were taken at the physicians’ discretion and were processed at the Microbiology Laboratory by previously described conventional standard culture, identification, and antimicrobial susceptibility testing methods.10 EUCAST 2023 clinical breakpoints were used to define antibiotic susceptibility. Neumococcal serotyping was performed in the Spanish National Microbiology Centre.

The study was grouped into four 5-year periods (2000–2004, 2005–2009, 2010–2014, and 2015–2019) to evaluate possible changes in the incidence of AM and microbiological detection rates. The incidence rate was expressed as the number of AM episodes/10,000 pediatric emergency department visits/year. Data are summarized as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables. Categorical variables were compared with χ2 or Fisher's exact test and continuous variables with Mann–Whitney U test. The percentage change (PC) in the incidence rate and in the prevalence of each microorganism isolated within the study periods were estimated to characterize trends, with log-transformed data models. Data were analyzed using Joinpoint Regression software v4.9.0.0 (Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute) and IBM-SPSS Statistics Version 25.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). All calculated p-values were two-sided, and an alpha level of 0.05 was used to assess significance.

This study was approved by Ethics Committee of Gregorio Marañón University Hospital.

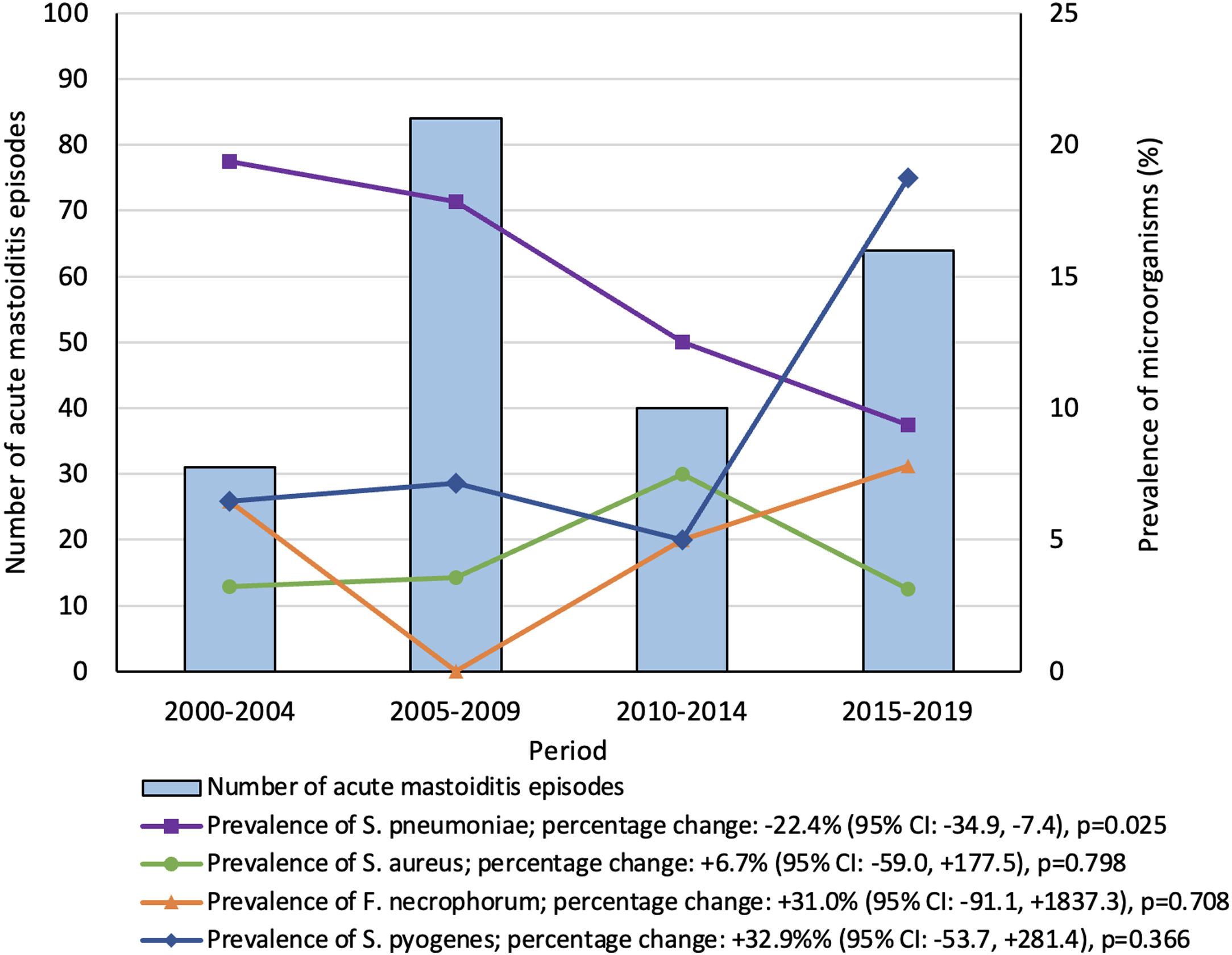

ResultsA total of 219 episodes from 209 patients were included; 125 (60%) were male and the median age was 19 (IQR 13–35) months. The number of cases in each period is included in Fig. 1. The incidence rate of AM remained stable during the study period (PC: +27.2% [95% confidence interval (CI): −32.6, +139.8]; p=0.163), with an average of 2.2cases/10,000 visits/year.

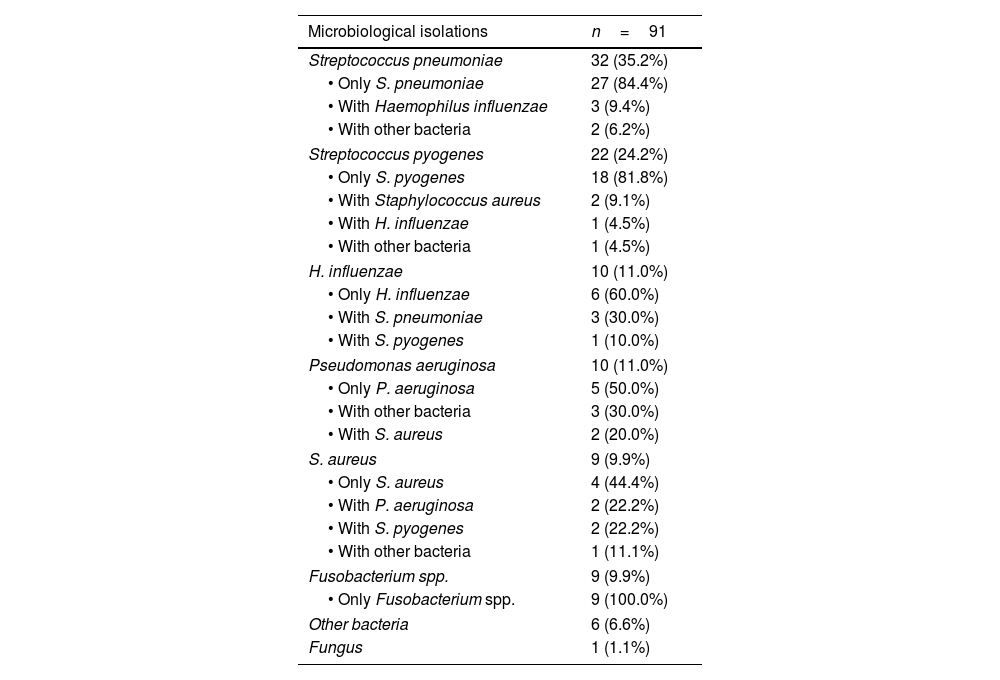

In 202 (92%) episodes a microbiological sample was collected and in ninety-one of these (45%), a microbiological isolation was achieved (Table S1). The microbiological positivity yield remained stable throughout the study periods (PC: +4.0% [95% CI: −20.0, +52.2]; p=0.704). The most common microorganism detected was S. pneumoniae (35%; 32/91), followed by S. pyogenes (24%; 22/91) (Table 1).

Episodes of acute mastoiditis with a positive culture.

| Microbiological isolations | n=91 |

|---|---|

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 32 (35.2%) |

| • Only S. pneumoniae | 27 (84.4%) |

| • With Haemophilus influenzae | 3 (9.4%) |

| • With other bacteria | 2 (6.2%) |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 22 (24.2%) |

| • Only S. pyogenes | 18 (81.8%) |

| • With Staphylococcus aureus | 2 (9.1%) |

| • With H. influenzae | 1 (4.5%) |

| • With other bacteria | 1 (4.5%) |

| H. influenzae | 10 (11.0%) |

| • Only H. influenzae | 6 (60.0%) |

| • With S. pneumoniae | 3 (30.0%) |

| • With S. pyogenes | 1 (10.0%) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 10 (11.0%) |

| • Only P. aeruginosa | 5 (50.0%) |

| • With other bacteria | 3 (30.0%) |

| • With S. aureus | 2 (20.0%) |

| S. aureus | 9 (9.9%) |

| • Only S. aureus | 4 (44.4%) |

| • With P. aeruginosa | 2 (22.2%) |

| • With S. pyogenes | 2 (22.2%) |

| • With other bacteria | 1 (11.1%) |

| Fusobacterium spp. | 9 (9.9%) |

| • Only Fusobacterium spp. | 9 (100.0%) |

| Other bacteria | 6 (6.6%) |

| Fungus | 1 (1.1%) |

Data are reported as absolute numbers and percentages, with the denominator being the total number of episodes of acute mastoiditis with a microbiological isolation (n=91). The percentages of the different combinations within each microorganism were calculated based on the number of episodes of acute mastoiditis where that microorganism was isolated.

By evaluating the trends in the prevalence of each microorganism within the study periods (Fig. 1), there was a significant decrease in the prevalence of S. pneumoniae (PC: −22.4% [95% CI: −34.9, −7.4]; p=0.025), from 19% in the first to 9% in the last period. Serotypes were evaluated in 56% (18/32) of S. pneumoniae isolations, none of them in the 2000–2004 period. Serotype 19A was the most frequent in the 2005–2009 (75%; 9/12) and 2010–2014 (50%; 2/4) periods; and 22F (100%; 2/2), in the 2015–2019 period. Serotypes contained in the PCV13 significantly decrease from 92% (11/12) in the pre-PCV13V period (2000–2009) to 33% (2/6) in the post-PCV13V period (p=0.022). Non-susceptibility to standard dosage of penicillin (75% vs. 27%; p=0.022) and cefotaxime (63% vs. 9%; p=0.08), and resistance to erythromycin (69% vs. 27%; p=0.034) significantly decreased from the pre-PCV13V to the post-PCV13V period (Table S2). Resistance to those antibiotics was associated with 19A serotype (p=0.002, p=0.013 and p=0.002, respectively).

S. pyogenes was the main microorganism isolated in the last study period, showing a significant increase in its prevalence from 5% to 19%, when comparing the third and the last study periods (p=0.046). Additionally, the incidence rate of S. pyogenes AM episodes increased from 0.1 to 0.6 cases/10,000 visits/year (p=0.003) between the same study periods.

DiscussionWe have evaluated the epidemiology of AM in a pediatric Spanish series admitted to our hospital during a 20-year period, including pre- and post-PCV periods. Although the overall incidence rate of AM remained stable, there was a decrease in the prevalence of S. pneumoniae within the study periods after the inclusion of PCV. Interestingly, there was a significant increase in the prevalence of S. pyogenes in the last period, being the leading cause of AM between 2015 and 2019.

Our study covers a wide period, including the introduction of PCV7 and PCV13 in the RIP. Although we lack individual data on pneumococcal vaccination for our cohort, there are high vaccination coverages (>95%) in our area,11 except for 2012–2015 when PCV13 was only available for private purchase and coverage decreased to 67%.4

As observed in our study, Laursen et al. described a decreased prevalence from 44% to 10% in pneumococcal AM after PCV implementation in Denmark.7 Similar results were reported in Israel.5 In Spain, although there is no specific data on AM, a recent study in Madrid showed a significant decrease in the prevalence of S. pneumoniae pneumonia in a similar period.12 We also observed a decrease in the prevalence of serotypes included in the PCV13 after its implementation, as well as a decrease in antibiotic resistance, as previously reported.3

As opposed to S. pneumoniae, we observed an increase in S. pyogenes isolation in our study, being the leading cause of AM in children during the last study period. S. pyogenes has also been reported to be the most common organism isolated in AM samples in the post-PCV era in other populations,7 and its incidence has increased in community-acquired pneumonia in Spain as well.12 Therefore, although a sharp increase in the incidence of invasive S. pyogenes infections has been recently reported,13 this trend may have begun in the pre-COVID-19 period.

Fusobacterium spp. has been increasingly reported as an important cause of AM in children.8 In our cohort, we also observed a non-statistically significant rise in its prevalence (Fig. 1).

Beyond these etiological changes, the overall incidence of AM did not change during the study period, as seen in other settings.5,6 Since PCV7 was introduced into immunization programs globally after 2000, and PCV13 after 2010, we are now observing the effects of these interventions. Continuous epidemiological surveillance is essential to assess middle and long-term outcomes, as serotype replacement may occur,3 which could induce new epidemiological changes in infections caused by S. pneumoniae.

The main limitation of our study is its retrospective nature. Unfortunately, because of this limitation, the availability of neumococcal serotypes was low, since it is not performed in regular bases. The microbiological positivity yield was relatively low (45%) compared to similar studies,2 but remained stable during the study period. As ear discharge samples were included, the isolation of certain microorganisms in this samples should be interpretated with caution, especially Pseudomonas and S. aureus, as they rather be skin colonizers.

As strength, we believe this is one of the largest studies evaluating the epidemiology of AM in children within such a long period, which enables the analysis of several years before and after the implementation of PCV. To note, the last year included in our study was 2019, and therefore, the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic did not influence our results. Since this is a single center study, more research is needed to generalize our results in similar populations.

In conclusion, although the incidence of AM in children remained stable in our study, the prevalence of S. pneumoniae significantly decreased in the post-PCV era, with S. pyogenes becoming the main microorganism isolated after the implementation of PCV13. Continuous epidemiological surveillance is crucial to assess this trend and to evaluate the impact of future new vaccines.

FundingThis study did not receive any funding.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Mar Santos-Sebastián, Felipe González Martínez and Gracia Aránguez Moreno as part of the Mastoiditis-Gregorio Marañón study group.