The rapid and complex evolution of bacterial resistance mechanisms in Klebsiella pneumoniae producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases and carbapenemases in Klebsiella pneumoniae is one of the most significant threats to public health. However, questions and controversies regarding the interactions between resistance and virulence in multidrug-resistant K. pneumoniae isolates remain unclear.

MethodsA retrospective cohort study was performed with 100 K. pneumoniae isolates recovered from a tertiary care university hospital centre in Lisbon over a 31-year period. Resistance and virulence determinants were screened using molecular methods (PCR, M13-PCR and MLST).

ResultsThe predominant virulence profile (fimH, mrkDv1, khe) was shared by all isolates, indicative of an important role of type 1 and 3 fimbrial adhesins and haemolysin, regardless of the type of β-lactamase produced. However, accumulation of virulence factors was identified in KPC-3-producers, with a higher frequency (p<0.05) of capsular serotype K2 and iucC aerobactin when compared with non-KPC-3 β-lactamases or carbapenemases. Additionally, 9 different virulence profiles were found, indicating that the KPC-3 carbapenemase producers seem to adapt successfully to the host environment and maintain virulence via several pathways.

ConclusionThis study describes an overlapping of multidrug-resistance and virulence determinants in ST-14K2 KPC-3 K. pneumoniae clinical isolates that may impose an additional challenge in the treatment of infections caused by this pathogen.

La rápida y compleja evolución de los mecanismos de resistencia de Klebsiella pneumoniae productora de beta-lactamasas de espectro extendido y carbapenemasas en Klebsiella pneumoniae es una de las amenazas más importantes para la salud pública. Sin embargo, aun existe controversia sobre la interacción entre la resistencia y la virulencia en aislados de K. pneumoniae resistentes a múltiples antimicrobianos.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio de cohorte retrospectivo con 100 aislados de Klebsiella pneumoniae de un centro hospitalario universitario en Lisboa durante 31 años. Los determinantes de la resistencia y virulencia se rastrearon utilizando métodos moleculares (PCR, M13-PCR y MLST).

ResultadosTodos los aislados compartían un perfil de virulencia predominante (fimH, mrkDv1, khe), lo que indica un papel importante de las adhesinas fimbriales de tipo 1 y 3, y de la hemolisina, independientemente del tipo de β-lactamasa producida. Sin embargo, la acumulación de factores de virulencia del serotipo capsular K2 y la aerobactina iucC se identificó con una mayor frecuencia en las cepas productoras de KPC-3 (p<0,05) en comparación con las productoras de otras β-lactamasas o carbapenemasas. Además, se encontraron 9 perfiles de virulencia diferentes, indicativos de que las cepas productoras de carbapenemasa KPC-3 parecen adaptarse con éxito al entorno y mantener la virulencia por varias vías.

ConclusiónEste estudio describe la unión de resistencia a múltiples antimicrobianos junto con determinantes de virulencia en aislados clínicos de K. pneumoniae ST-14K2 KPC-3 lo que puede suponer un desafío adicional en el tratamiento de infecciones causadas por este patógeno.

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a leading cause of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), mainly responsible for urinary, respiratory and bloodstream infections and is now recognized as an urgent threat to public health.1 Since the first broad-spectrum β-lactamase TEM-1, the rapid evolution of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL) and carbapenemases, are one of the most significant epidemiologic changes in infectious diseases.2 In Portugal, the first carbapenemase was reported in 20093 and an important hospital-wide dissemination has been reported previously.4 However, the molecular determinants of virulence and resistance were not described to date.

Factors that are implicated in the virulence of K. pneumoniae isolates can include the capsular serotype, iron-scavenging systems, fimbrial and non-fimbrial adhesins,5 which have an important role in the development of the infection.6 This knowledge can be fundamental to support efforts to control the threat to human health posed by this bacterium with the purpose of recognize or understand the emergence of clinically important clones within this highly genetically diverse species.7 Despite this, there remains a lack of data regarding the virulence genes carried by K. pneumoniae producing beta-lactamases8 and, particularly little is known about the virulence potential of KPC-producers.9

The aim of this study was evaluate the correlation of bacterial resistance and virulence determinants among K. pneumoniae isolates collected over a period of 31 years in a single tertiary-care university hospital centre.

MethodsHospital centre setting and bacterial isolatesThe K. pneumoniae isolates selected for this study were collected between 1980 and 2011 from patients hospitalizaed at a tertiary care university hospital centre located in Lisbon, with approximately 1100 beds that provides direct care to a population of 370,000 people. All isolates were recovered from inpatients using standard operating procedures and identified as β-lactamase-producers by the laboratory, using conventional methods or automated systems like Vitek2® (BioMérieux, Marcy, l’Étoile, France) or MicroScan® (Snap-on, Kenosha, WI, USA). The isolates were also sent to the Microbiology laboratory for additional studies. All isolates were maintained frozen in BHI broth plus 15% glycerol at −80°C. For analysis, the strains were grown in BHI Broth for 18h at 37°C and seeded in nutrient agar or LB agar.

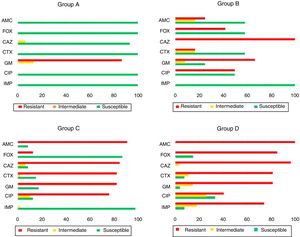

The K. pneumoniae strains were selected according to the isolation period and the beta-lactamase type produced (determined by preliminary antibiotic susceptibility profile) and within this, by random selection. The selected K. pneumoniae isolates were then classified in 4 groups: group A (1980–1989, 15 strains susceptible to β-lactams, excluding aminopenicillins, indicative of broad-spectrum β-lactamases – BSBL production); group B (1990–2001, 12 strains with resistance to ceftazidime and reduced susceptibility to cefotaxime, indicative of TEM-type extended spectrum β-lactamases – ESBL production), group C (2002–2008, 48 strains with resistance to ceftazidime and cefotaxime, indicative of the production of CTX-M-type extended spectrum β-lactamases – ESBL); group D (2009–2011), 27 strains with resistance to carbapenems, indicative of carbapenemase production.

Among the 100 isolates that were characterized in this study, 88 were clinical isolates: urine (n=31); blood (n=21), pus (n=17), sputum (n=17), catheter (n=1) and cerebrospinal fluid (n=1). The remaining 12 isolates, included in group A, were from one colonized healthcare professional (n=1), colonized patients (n=7) and hospital environmental isolates like surfaces and medical equipment (n=4). The isolates were recovered in 26 wards or ICUs, mainly in medical and cardiothoracic surgery wards.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testingAntimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed following the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) guidelines by the standardized disk diffusion method in Mueller-Hinton agar medium. Quality controls were carried out in accordance with EUCAST (version 6.0, 2016), and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (M100-S20), namely Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Escherichia coli ATCC 35218. All isolates were tested with the same panel of antibiotics as follows: amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (20μg/10μg), cefoxitin (30μg), cefotaxime (5μg), ceftazidime (10μg), imipenem (10μg), gentamicin (10μg), and ciprofloxacin (5μg). Isolates belonging to group B, C and D were also tested for tigecycline (15μg) and fosfomycin (200μg) in order to evaluate the role of these antibiotics as alternative therapeutic options.

The inhibition zones were interpreted according to EUCAST, with the exception of fosfomycin, that was interpreted following the CLSI guidelines. The isolates were categorized as susceptible (S), intermediate (I) and resistant (R) by applying the breakpoints in the phenotypic test results. The imipenem minimum inhibitory concentration (MICs) was determined by the agar gradient test (E-test®, Biomérieux, France) following the EUCAST guidelines.

Resistance and virulence determinantsPCR based screening for the most commonly found β-lactamase families was performed with specific primers (blaSHV, blaDHA, blaCMY, blaCTX-M) including carbapenemase genes (blaKPC, blaIMP, blaVIM and blaOXA).10 The virulence factors were assessed by PCR with specific primers for K2 serotype (K2A), fimbrial adhesins type 1 (fimH) and type 3 (mrkDv1 and mrKDV2-4), haemolysin (khe), aerobactin (iucC), mucoid (rmpA) and hypermucoviscosity phenotype (magA). The primers were designed in our study (Table 1).

Primers used in this study for the detection of beta-lactamases and virulence genes.

| Gene | DNA sequence (5′ to 3′) | Amplicon size (bp) | EMBL accession number (Genbank) |

|---|---|---|---|

| blaTEM | F: GAAAGGGCCTCGTGATACR: TTACCAATGCTTAATCAGTGA | 1058 | HM749966 |

| blaNDM | F: TATCGCCGTCTAGTTCTGCTGR: ACTGCCCGTTGACGCCCAAT | 871 | AB604954 |

| K2A | F: CAACCATGGTGGTCGATTAGR: TGGTAGCCATATCCCTTTGG | 531 | EF221827 |

| fimH | F: TGTTCACCACCCTGCTGCTGR: CACCACGTCGTTCTTGGCGT | 512 | NC_012731.1 |

| mrkDV1 | F: CGGTGATGCTGGACATGGTR: CCTCTAGCGAATAGTTGGTG | 300 | EU682505.2 |

| mrkDV2-4 | F: CTTAATGGCGMTGGGCACCAR: TCATATGCGACTCCACCTCG | 950 | AY225463.1AY225464.1AY225465.1 |

| khe | F: TGATTGCATTCGCCACTGGR: GGTCAACCCAACGATCCTGG | 428 | NC_012731.1 |

| iucC | F: GTGCTGTCGATGAGCGATGCR: GTGAGCCAGGTTTCAGCGTC | 944 | NC_005249.1 |

| rmpA | F: ACTGGGCTACCTCTGCTTCAR: CTTGCATGAGCCATCTTTCA | 516 | NC_012731.1 |

| magA | F: TCTGTCATGGCTTAGACCGATR: GCAATCGAAGTGAAGAGTGC | 1137 | NC_012731.1 |

F: forward primer; R: reverse primer.

Polymerase chain reactions were performed using the commercial kit puReTaq Ready-To-Go PCR Beads (GE Healthcare®) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Subsequently the PCR products were resolved in agarose gel 1%, in TBE (1×), and stained with GelRed (Biotium). Positive and negative controls were included in all PCR assays. Resulting PCR products were submitted to purification using the JETquick Spin Column Technique PCR Purification Kit (Genomed®), according to producer's instructions and were sequenced at Macrogen Korea and STABVida Portugal. Searches for nucleotide sequences were performed with the BLAST program, available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information Web site (http://www.ncbi.nim.nih.gov/). Multiple-sequence alignments were performed with the ClustalX program, available at the European Bioinformatics Institute Web site (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2).

Molecular typing by M13-PCR fingerprintingClonal relatedness was established by M13-PCR fingerprinting, based on randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis.11 Strains classified as genetically related and assigned to the same lineage were identified with letters (A–Z). Different numbers were assigned to more closely related strains (≤2 bands) and differentiate member's types as subtypes (e.g., A1, A2).

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST)MLST was performed as previously described12 on 25 selected isolates representing each of the β-lactamases currently with more clinical relevance: CTX-M-15 (n=8) and KPC-3 (n=17). The sequences were performed at Macrogen Korea and submitted to the MLST database for allele attribution. The Klebsiella pneumoniae database is available at the Pasteur MLST site (http://www.pasteur.fr/mlst/). Last accessed at May 2, 2018.

Statistical analysisThe statistical significance of comparisons made throughout this study was carried out by Fisher Exact Test, for which we used the computer program available in http://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/index. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical approvalIsolates were obtained as part of routine diagnostic testing and were analyzed anonymously. All data were collected in accordance with the European Parliament and Council decision for the epidemiological surveillance and control of communicable disease in the European Community. Epidemiological data were collected from clinical records. The study proposal was also approved by Research Ethics Committee of Faculty of Medicine, University of Lisbon, Portugal.

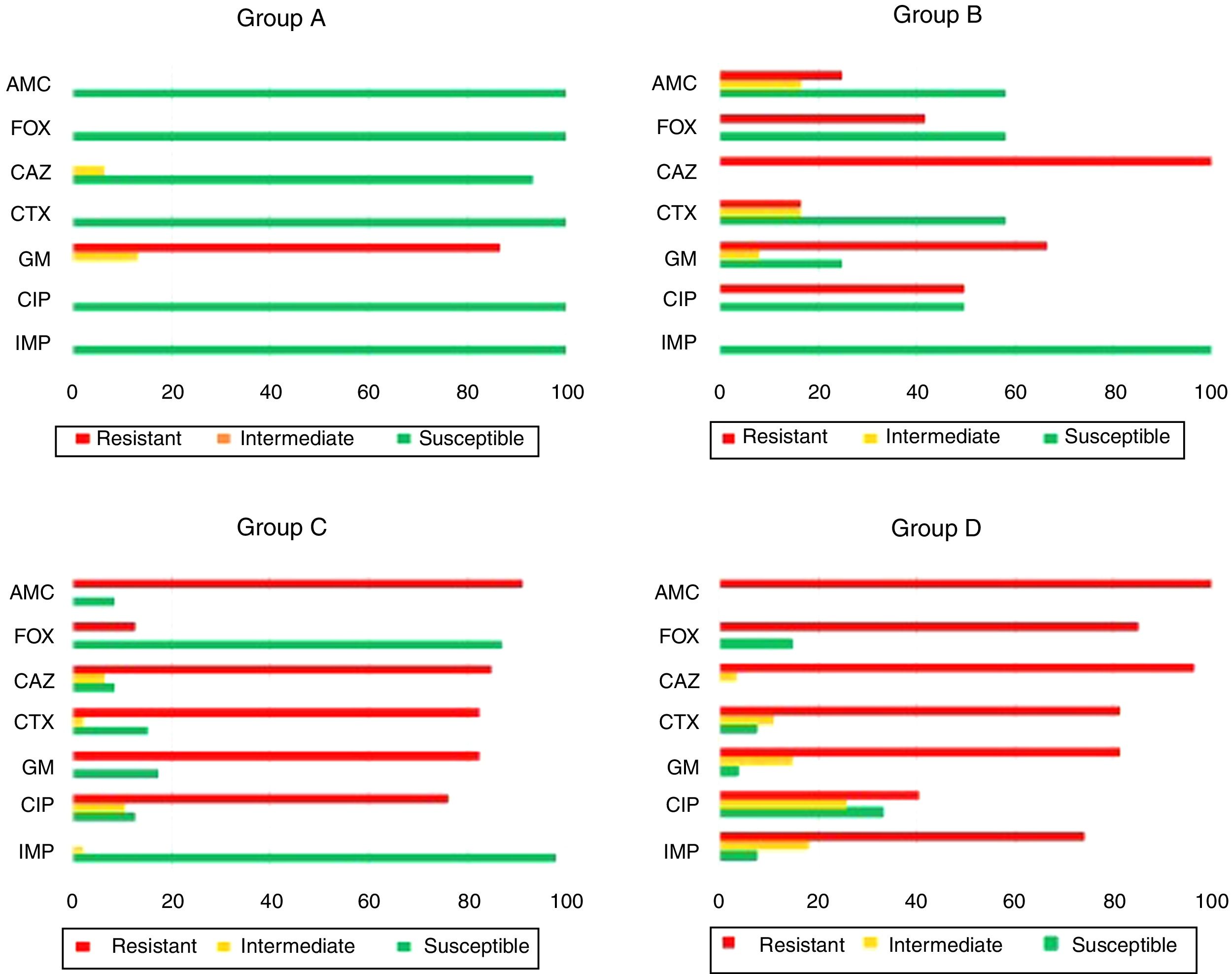

ResultsAntimicrobial susceptibility patternsThis study included the susceptibility profile of K. pneumoniae strains isolated from 1980 to 2011 against a uniform panel of antibiotics (Fig. 1). All isolates from group A except one (93.3%, 14/15) were susceptible to all cephalosporins and 13 isolates showed resistance to gentamicin (86.7%, 13/15). All the strains included in group B (n=12) were resistant to ceftazidime (100.0%, 12/12). Moreover, 66.7% (8/12) and 50.0% (6/12) showed resistance to gentamicin and ciprofloxacin. Among the isolates of group C it was observed that 84.8% (39/46) and 82.6% (38/46) of the isolates were resistant to ceftazidime and cefotaxime, respectively. Additionally, resistance to gentamicin (82.6%, 38/46) and ciprofloxacin (76.1%, 35/42) was also found.

Among the 27 strains belonging to group D, 96.3% (26/27) were resistant to cefotaxime and ceftazidime, 74.1% of isolates (20/27) were resistant to imipenem while 81.5% (22/27) and 40.7% (11/27) were resistant to gentamicin and ciprofloxacin, respectively.

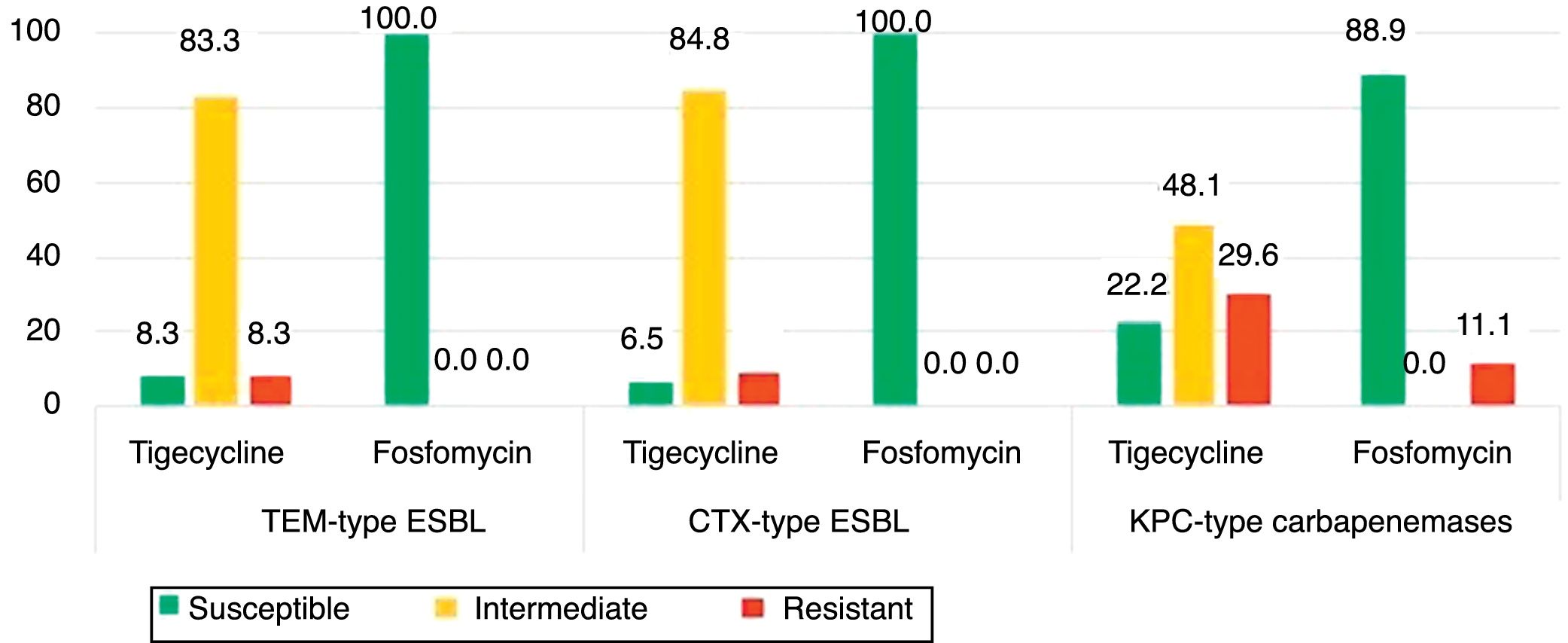

The isolates of groups B–D were also tested for tigecycline and fosfomycin in order evaluate the role of these antibiotics as an alternative therapeutic option as well to understand the evolution of their resistance patterns over the study period (Fig. 2). Fig. 2 shows the phenotypic characterization of K. pneumoniae isolates. The isolates resistant to tigecycline found ranged from 8.3% (1/12) among broad-spectrum β-lactamase producers, to 29.6% (8/27) in carbapenemase producers. A high frequency of isolates with clinically intermediate susceptibility to tigecycline was found (ranging from 48.1% to 83.3%) when compared with fosfomycin (0%). The susceptibility to fosfomycin was 100% (broad and extended-spectrum β-lactamases producers) and 88.9% (period 2009–2011). Fosfomycin showed the highest activity to all β-lactamase-producing isolates (88.9%) (Fig. 1), in comparison with gentamicin (3.7%) or ciprofloxacin (33.3%).

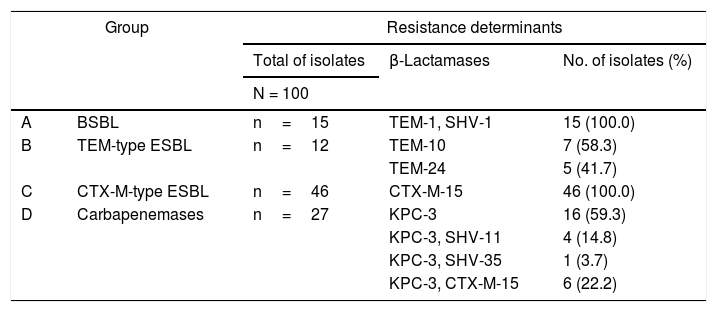

Identification of the β-lactamasesResults of the identification of β-lactamases in K. pneumoniae are shown in Table 2. The 15 K. pneumoniae isolates in group A (1980–1989) presented both TEM-1 and SHV-1 broad-spectrum β-lactamases. Among the 12 isolates in group B (1990–2001), seven (58.3%, 7/12) presented the TEM-10 and five (41.7%, 5/12) the TEM-24 extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL). All 46 isolates (100.0%, 46/46) in group C (2002–2008) were positive for cefotaxime-hydrolyzing CTX-M-15 ESBL. The 27 isolates in group D (2009–2011) presented the KPC-3 carbapenemase alone (59.3%, 16/27) or in combination with other β-lactamases, namely the broad-spectrum β-lactamase SHV-11 (14.8%, 4/27) and the ESBL SHV-35 (3.7%, 1/27) and CTX-M-15 (22.2%, 6/27). The genes blaDHA, blaCMY, blaIMP, blaVIM, blaNDM and blaOXA were not detected in our collection.

Resistance determinants found in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates (n=100) recovered over a 31-year period in a tertiary care hospital centre in Lisbon, Portugal.

| Group | Resistance determinants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total of isolates | β-Lactamases | No. of isolates (%) | ||

| N = 100 | ||||

| A | BSBL | n=15 | TEM-1, SHV-1 | 15 (100.0) |

| B | TEM-type ESBL | n=12 | TEM-10 | 7 (58.3) |

| TEM-24 | 5 (41.7) | |||

| C | CTX-M-type ESBL | n=46 | CTX-M-15 | 46 (100.0) |

| D | Carbapenemases | n=27 | KPC-3 | 16 (59.3) |

| KPC-3, SHV-11 | 4 (14.8) | |||

| KPC-3, SHV-35 | 1 (3.7) | |||

| KPC-3, CTX-M-15 | 6 (22.2) | |||

BSBL: broad-spectrum β-lactamase; ESBL: extended-spectrum β-lactamase.

Virulence genes as fimH and mrkD adhesins, khe toxin, iucC siderophore, K2 capsular type as well the magA and rmpA gene that confers a hypermucoviscosity and mucoid phenotype, were investigated in all K. pneumoniae isolates. A prevalence of fimH (96.0%), mrkDv1 (90.0%), khe (63.0%) and K2 (23.0%) virulence genes was identified. Only 6.0% of the isolates showed the mrkDV2-4 and iucC gene. No magA and rmpA genes were amplified. All isolates analyzed (n=100) presented at least one of the virulence genes studied.

The distribution of virulence genes by the β-lactamase type produced is shown in Table 3. The fimbrial adhesins fimH (80.0–100.0%), mrkDV1 (66.7–97.8%) and hemolysin gene khe (52.2–91.7%) were identified in all K. pneumoniae β-lactamase types, although the iucC gene was only identified in KPC-3 (22.0%). The K2 gene was identified in TEM-1/SHV-1 (26.7%), TEM-10/TEM-24 (25.0%) and KPC-3 producers (59.0%). The mrkDV2–4 gene was more frequent (p<0.05) among the TEM-BSBL isolates (26.7%) compared with TEM-ESBL (0.0%), CTX-M-15 (2.2%) and KPC-3 (3.7%). The K2 and iucC virulence genes were significantly related with KPC-3 clinical isolates compared with strains with other β-lactamases (p=0.0267 and p=0.0002, respectively).

Distribution of virulence factors and their respective genes among Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates producing different types of β-lactamases.

| Virulence factor | Target gene | β-LactamasesNumber of isolates (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSBL | TEM-type ESBL | CTX-M-type ESBL | Carbapenemases | Total | ||||

| TEM-1/SHV-1 | TEM-10/TEM-24 | CTX-M-15 | KPC-3 | |||||

| n=15 | n=12 | n=46 | n=27 | N=100 | ||||

| Fimbrial adhesins | Type 1 | fimH | 12 (80.0) | 12 (100.0) | 46 (100.0) | 26 (96.3) | 96 (96.0) | |

| Type 3 | Variant 1 | mrkDV1 | 10 (66.7) | 9 (75.0) | 45 (97.8) | 26 (96.3) | 90 (90.0) | |

| Variant 2–4 | mrkDV2–4 | 4 (26.7) | 0.0 | 1 (2.2) | 1 (3.7) | 6 (6.0) | ||

| Toxin | Haemolysin | Khe | 12 (80.0) | 11 (91.7) | 24 (52.2) | 16 (59.0) | 63 (63.0) | |

| Capsular type | K2 serotype | K2A | 4 (26.7) | 3 (25.0) | 0.0 | 16 (59.0)* | 23 (23.0) | |

| Siderophore | Aerobactin | iucC | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6 (22.0)* | 0.0 | |

| Protectines or invasins | Mucoviscosity phenotype | magA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Regulator of mucoid phenotype | rmpA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

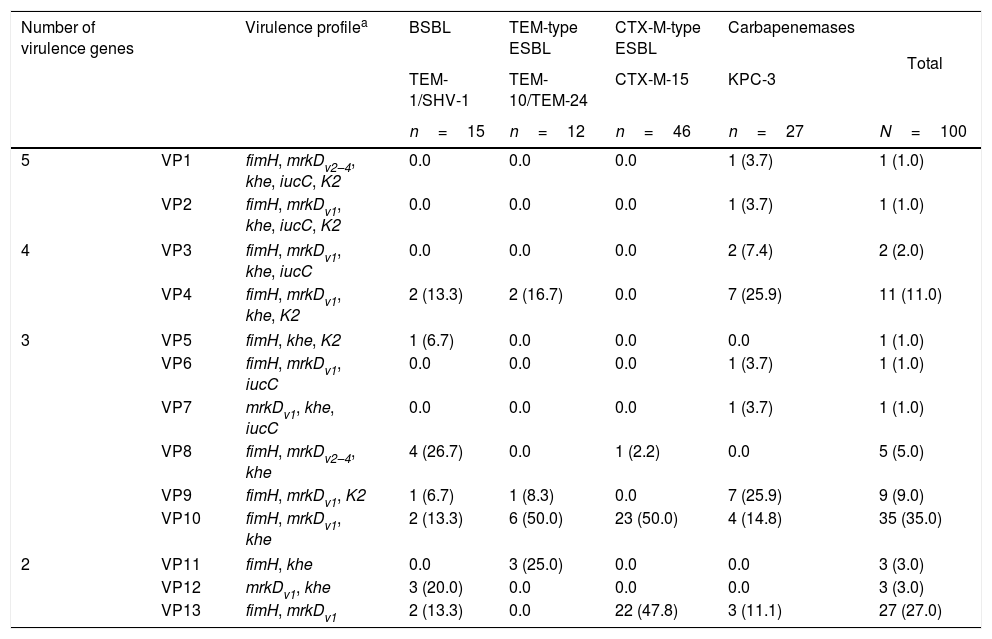

The characterization of the virulence profile (VP) was performed in order to evaluate the simultaneously accumulation of virulence genes in the same isolate, and numbered according the decreasing number of virulence genes found (Table 3). According to Table 4, three virulence profiles were predominant, namely VP10 (35.0%), VP13 (27.0%) and VP4 (11.0%). The prevalent profiles found in the β-lactamase-producing K. pneumoniae isolates were those that presented less accumulation of virulence genes per isolate, namely the VP1–3 (2 genes), VP10 (3 genes) and, finally, VP4 (4 genes). The VP10 (fimH, mrkDv1, khe) was found in 35 isolates (35.0%) and was shared by all β-lactamase producers, namely by TEM-1 and SHV-1 (13.3%), TEM-10 and TEM-24 (50.0%), CTX-M-15 (50.0%) and KPC-3 (14.8%). The VP13 (fimH, mrkDv1) was found among 27 (27.0%) strains and was mainly detected in CTX-M-15 producers. Instead, the VP4 (fimH, mrkDv1, khe, K2) was specifically found in KPC-3 producers. KPC-3 isolates showed 9 virulence profiles (all except VP5, -8, -11 and -12) whereas in CTX-M-15 producing-isolates only 3 were detected (VP10, -13 and -8).

Virulence profiles and number of virulence genes identified in isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing different types of β-lactamases and carbapenemases.

| Number of virulence genes | Virulence profilea | BSBL | TEM-type ESBL | CTX-M-type ESBL | Carbapenemases | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEM-1/SHV-1 | TEM-10/TEM-24 | CTX-M-15 | KPC-3 | ||||

| n=15 | n=12 | n=46 | n=27 | N=100 | |||

| 5 | VP1 | fimH, mrkDv2–4, khe, iucC, K2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 (3.7) | 1 (1.0) |

| VP2 | fimH, mrkDv1, khe, iucC, K2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 (3.7) | 1 (1.0) | |

| 4 | VP3 | fimH, mrkDv1, khe, iucC | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2 (7.4) | 2 (2.0) |

| VP4 | fimH, mrkDv1, khe, K2 | 2 (13.3) | 2 (16.7) | 0.0 | 7 (25.9) | 11 (11.0) | |

| 3 | VP5 | fimH, khe, K2 | 1 (6.7) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 (1.0) |

| VP6 | fimH, mrkDv1, iucC | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 (3.7) | 1 (1.0) | |

| VP7 | mrkDv1, khe, iucC | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 (3.7) | 1 (1.0) | |

| VP8 | fimH, mrkDv2–4, khe | 4 (26.7) | 0.0 | 1 (2.2) | 0.0 | 5 (5.0) | |

| VP9 | fimH, mrkDv1, K2 | 1 (6.7) | 1 (8.3) | 0.0 | 7 (25.9) | 9 (9.0) | |

| VP10 | fimH, mrkDv1, khe | 2 (13.3) | 6 (50.0) | 23 (50.0) | 4 (14.8) | 35 (35.0) | |

| 2 | VP11 | fimH, khe | 0.0 | 3 (25.0) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3 (3.0) |

| VP12 | mrkDv1, khe | 3 (20.0) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3 (3.0) | |

| VP13 | fimH, mrkDv1 | 2 (13.3) | 0.0 | 22 (47.8) | 3 (11.1) | 27 (27.0) | |

VP: virulence profile; BSBL: broad-spectrum β-lactamase; ESBL: extended-spectrum β-lactamase.

The clonal relatedness of the K. pneumoniae isolates was established by M13-PCR fingerprinting to address if there was a common clone between the group of different β-lactamase producing isolates or within the same β-lactamase group. A polyclonal situation was found with 33 different genotypes. No similar genotypes were identified among the different β-lactamases groups, indicating genetic variability. Despite this, genetically related isolates were identified within the same β-lactamase group as follows: in group A – broad-spectrum β-lactamases producing strains –, with seven colonized patients and four environmental isolates, all from neonatology department, shared the same genotype; in group C, CTX-M-15 β-lactamase producers, presented 4 main genotypes with isolates from different wards and, finally, in group D, 66.7% of the KPC-3 producers shared the same genotype (genotype A). The intensive care unit of hematologic diseases, the thoracic surgery department and the surgery observation room were the mainly affected wards, all sharing the KPC-3 type A genotype.

MLST was performed on CTX-M-15 (n=8) and KPC-3 (n=17)-producing clinical isolates for international comparative purposes. The ST15 accounted for 62.5% (5/8) of the CTX-M-15 isolates analyzed by MLST. Additionally, 5 distinct allelic profiles were found: ST133 (n=1); ST147 (n=1), ST276 (n=1) for CTX-M-15 producing isolates, whereas the KPC-3 carbapenemase-producing isolates were ST11 (n=2) and ST14 (n=15). The first two KPC-3 isolates, identified in 2009, showed the ST11 and the remaining KPC-3 isolates (2009–2011) exhibited the same combination of alleles across the seven sequenced loci, corresponding to the ST14 (88.2% of the KPC-3 isolates).

DiscussionMultidrug resistant and virulent populations were, for a long time, non-overlapping13 but the virulence of K. pneumoniae and the interplay between resistance and virulence is still poorly understood.14 Available reports do not include the KPC-3 isolates or ST14 clones15 and mainly report the hypermucoviscosity phenotype, associated with pyogenic liver abscess.16 To our knowledge, this is the first study that characterizes the evolution of virulence features of K. pneumoniae β-lactamase-producers, including carbapenemase producers recovered from patients with hospital-acquired infections.

A comparison of the population structure and virulence factors between groups of strains with ESBL and KPC resistance mechanisms versus broad-spectrum β-lactamase producers (BSBL) was performed. The BSBL strains showed a susceptibility profile to β-lactams and quinolones (>90%), that decreased to <60% among TEM-type ESBL producers and to <20% among CTX-M-type ESBL producers. It is of concern that KPC-3 carbapenemase producers were resistant to β-lactams, quinolones and aminoglycosides, limiting the therapeutic options to treat infections caused by these bacteria. According to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, the rate of resistance to carbapenems in Portugal has increased six-fold (0.3–1.8%) over the period from 2011 to 2014,17 highlighting that special attention should be paid to carbapenem resistance trends.

The rate of resistance to tigecycline among TEM- and CTX-M-type extended-spectrum β-lactamase producers was 8.5%, in line with previous reports that mentioned <10% resistance rates in wide-scale surveillance studies18 but surprisingly among carbapenem-resistant strains this resistance rate reached 30%, following the tigecycline commercialization in Portugal (2009). Of relevance, also 48% of the KPC-3 isolates presented intermediate susceptibility to tigecycline, a phenotype associated with uncertain clinical therapeutic effect.

Of note, 89% of KPC-3 isolates were susceptible to fosfomycin and the resistance rates found in all groups of isolates ranged from 8 to 11%, supporting fosfomycin as a therapeutic option for difficult-to-treat K. pneumoniae infections. The potential use of fosfomycin has been reported by other authors and its ability to penetrate through biofilm layers.19 However, the report of FosA3 (resistance to fosfomycin) and KPC-2 on a single plasmid and its likely clonal spread are worrying and should be monitored.20

Type 1 and type 3 fimbrial adhesins are mainly involved in adherence to several cell types and in biofilm formation21 which protects bacteria against antibiotics and host defenses19 and can act as a starting point of infection from medical devices.22 The high prevalence (>90%) of type 1 and type 3 fimbrial adhesins observed in our study, together with the antimicrobial multiresistance observed, can explain the persistence of this multiresistant isolates for long time in the hospital environment and the difficulty of their eradication. Out of 100 strains studied, 92 showed the fimH and mrkD genes in the same isolate, demonstrating a relation between these two genes. Additionally, the virulence profile VP10 (fimH, mrkDv1, khe) with the genes encoding type 1 and type 3 fimbrial adhesins and haemolysin, a pore-forming toxin that makes some nutrients available such as the ferrous ion in hemoglobin and often associated with pathogenic microorganisms,23 were predominant in the K. pneumoniae collection and were shared by all β-lactamase producers, conclusive of a common pathogenic origin.

The KPC-producing strains were previously described as highly resistant and low virulent strains and no specific virulence factors have been identified.24 Nevertheless, this conclusion is sustained in the absence of aerobactin and capsular K2 and mainly included KPC-2 isolates.24,25 In addition, Siu et al. reported that known virulence factors such as K1, K2, and K5 capsular polysaccharides, rmpA and the aerobactin gene were absent in KPC-producing isolates and that these strains present low virulence in murine lethality model.26

Our data contrast with previous studies considering a higher detection rate (p<0.05) of K2 capsular antigen (59%) and aerobactin (22%) in KPC-3 K. pneumoniae isolates than in the KPC-negative groups. The K2 antigen confers resistance to phagocytosis and serum resistance,27 being frequently associated with severe infections28 and aerobactin is one of the siderophores (extracellular ferric chelating agents) secreted by bacterial cells and play a critical role in bacterial virulence given that iron bioavailability in the host is extremely low and it is essential for microbial growth.29 Moreover, De Cassia Andrade Melo et al. reported the presence of type 1 and type 3 fimbrial adhesins and yersiniabactin siderophore in KPC-2-producing K. pneumoniae isolates from Brazil,2 a country maintaining a close relationship with Portugal. However, the bacterial sequence types of the isolates were not analyzed.

In conclusion, the ST14 KPC-3 K. pneumoniae clone has revealed a higher virulence profile diversity and ability to accumulate virulence genes in the same isolate, when compared with strains producing other β-lactamases. A deeper understanding of the virulence and resistance traits of high-risk clones is the first step toward the development of more effective approaches to minimize the impact of hospital acquired infections by multiresistant bacteria.

FundingThis work was supported by the Research Institute for Medicines (iMed.ULisboa), Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Lisbon.

Conflicts of interestJ. Melo-Cristino research grants administered through his university and honoraria for serving on speaker's bureaus of Pfizer, Gilead and Novartis. The other authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank to all the members of the Microbiology laboratory for the collaboration in isolation and identification of bacteria.