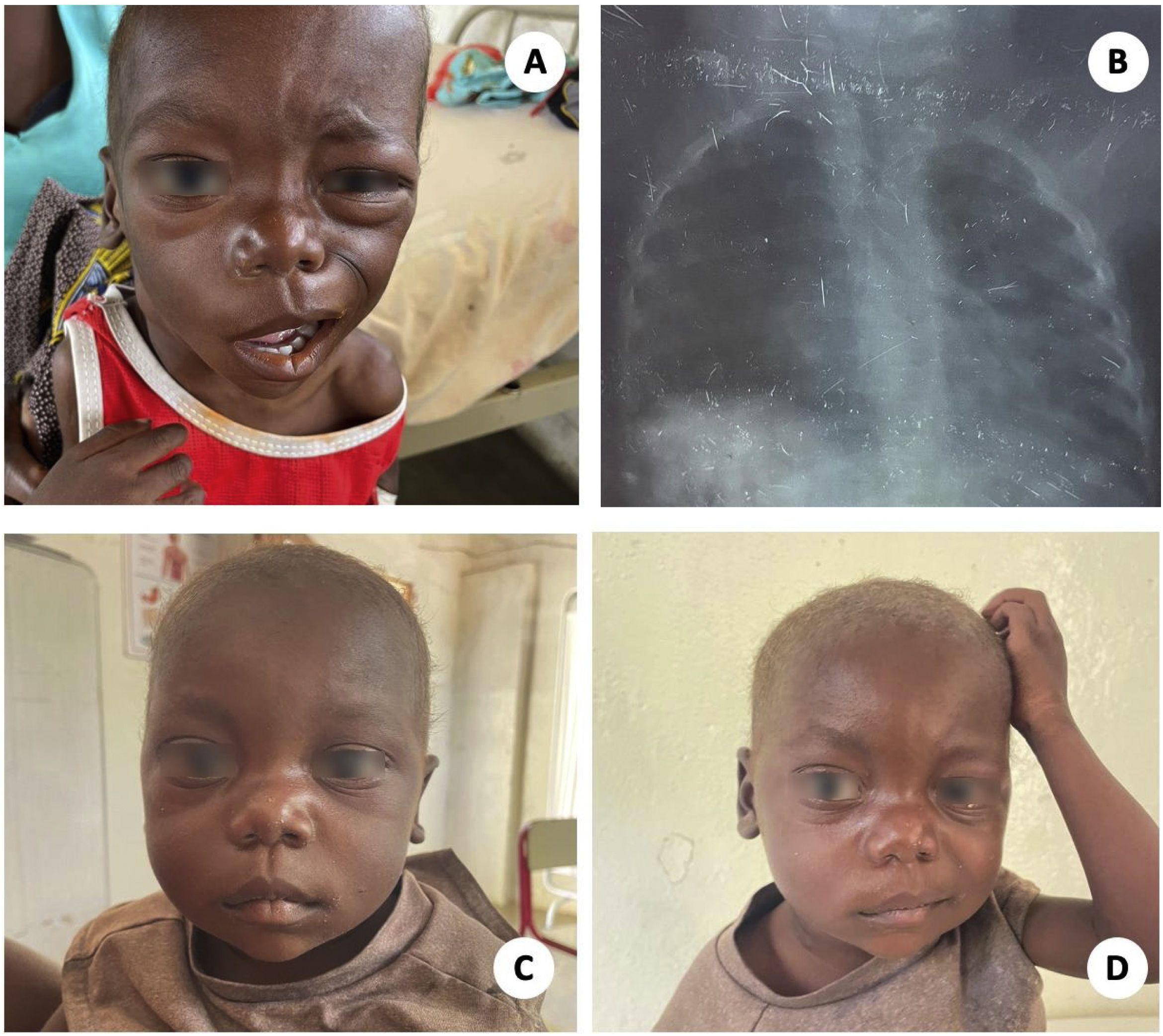

A 2-year-old boy was admitted to our hospital with a 4-month history of fever, cough, weight loss and right laterocervical swelling. Purulent discharge from the right cervical region and ear was reported. The father had been treated for pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) the year before. At the time of admission, the patient was afebrile, with proper oxygen saturation but tachycardic. He presented severe acute malnutrition (z-score −4 SD). Moreover, one could observe at a glance the presence of a large mass on the right laterocervical area without clear fistulas, hard on touch and which extended to the submandibular angle. Additionally, a right peripherical facial palsy could be noticed (Fig. 1). On chest auscultation, we heard left lung-base crackles.

EvolutionIn the chest X-ray, we observed a soft infiltrate in the left base without perihilar or mediastinal masses. Rapid capillary HIV test (Alere Determine HIV 1/2, Abbott) was negative. Molecular testing (Xpert MTB/RIF ultra, Cepheid) of a nasogastric aspirate sample was negative for TB, and later on, positive in a purulent sample taken from the ear. No rifampicin resistance was detected. Under the diagnosis of a peripheric facial palsy caused by a TB otomastoiditis associated to a cervical scrofula, standard four first-line TB treatment was initiated. Due to its absence, and the impossibility of transferring the patient to a tertiary hospital, no other radiological tests could be made. Given the impossibility to perform a surgical facial nerve decompression, corticosteroid treatment was considered but finally rejected due to the poor nutritional status and increased risk of infection. Local right-eye care was recommended. In addition, the patient presented a P. falciparum infection that was treated with an artemisinin-based regimen, received a short course of ceftriaxone for suspected left basal pneumonia as well as nutritional support with therapeutic milk. After two months of follow-up the child was gaining weight, systemic symptoms had disappeared and cervical swelling and facial palsy had improved (Fig. 1).

Final commentOtomastoiditis is a rare form of extrapulmonary TB (0.1% of all cases) accounting for less than 1% of chronic middle ear infections.1 It can occur by aspiration of mucus through the eustachian tube, by direct implantation through the external auditory canal, or as a result of hematogenous spread.2 Otorrhea is the main symptom reported. Although uncommon, the triad of painless otorrhea, multiple perforation of the tympanic membrane and peripheral facial palsy should raise suspicion of TB. Diagnosis is often delayed, especially in regions with a low burden of TB and in cases of chronic isolated non-painful otorrhea. Acid-fast staining, molecular testing and culture from local discharge or biopsy samples can give the diagnosis. Concomitant pulmonary involvement is reported in up to 50% of cases. Local complications such as tympanic perforation, hearing loss, mastoiditis, subperiosteal abscesses or facial paralysis are frequent and can lead to persistent sequelae. Intracranial extension is infrequent.3 Antituberculostatics given for 6–9 months is the mainstay of treatment. In case of complications, surgical approaches such as mastoidectomy or facial nerve decompression must be considered.

Authors’ contributionWe were all involved in the patient's care and diagnosis. S.A. and J.M.C. wrote the first draft of the manuscript which was edited and finally approved by G.P., A.N. and M.L.A.

Informed consentWritten consent for publication was obtained from the patient's mother.

Financial disclosureThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interests.