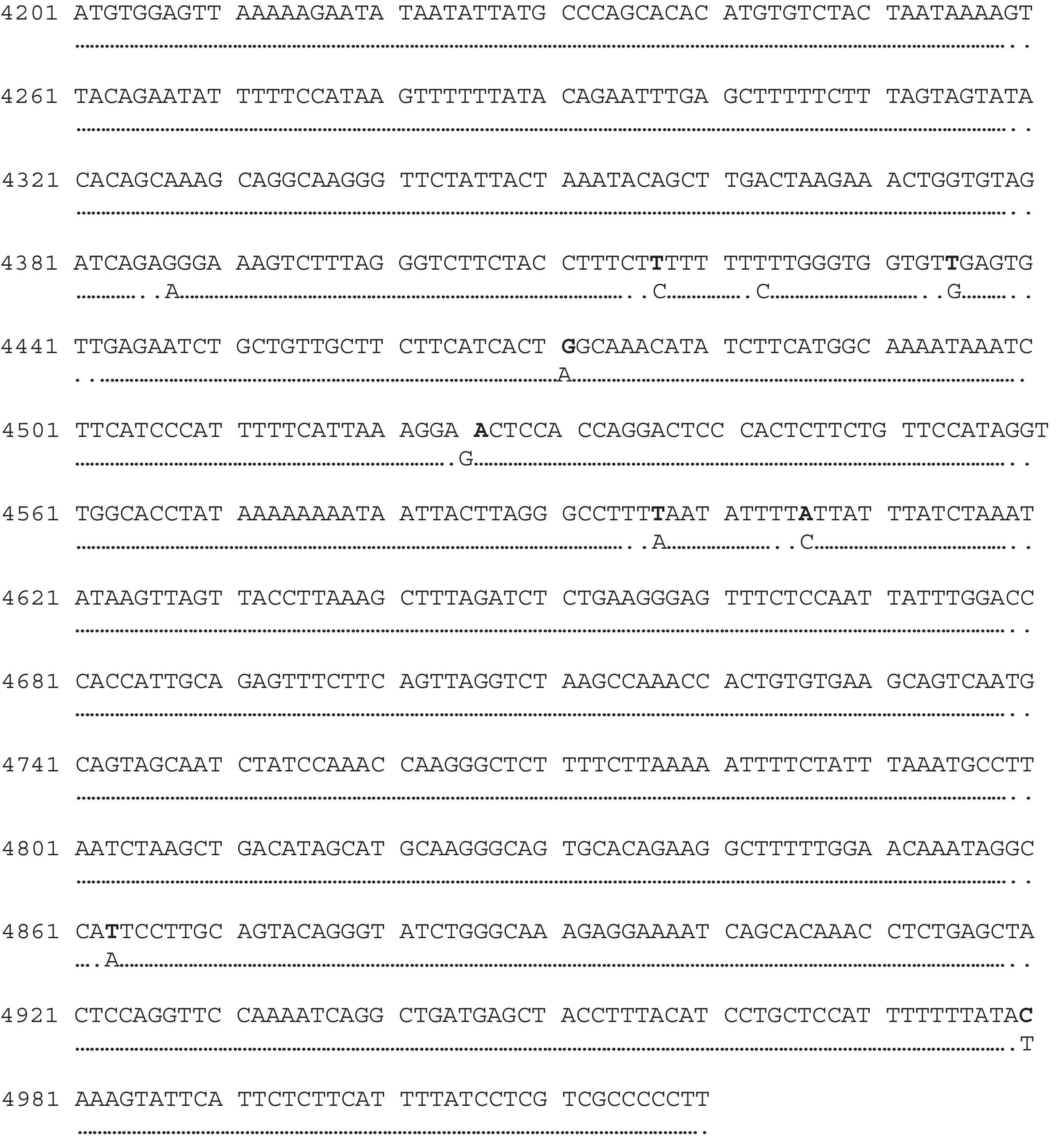

BK virus (BKV) is recognized as a cause of allograft failure in renal transplant recipients and may also be associated with renal dysfunction in other immunosuppressed patients. In particular, in patients who undergo hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, reactivation of BKV infection is associated with hemorrhagic cystitis.1 In addition, there is no proven therapy, so, on-time detection of BKV replication and fast reduction of immunosuppressive therapy are recommended to prevent the development of BKV-associated nephropathy.2 Quantitative real-time PCR assays have been developed, however, the significant variability in regions of the viral genome that are targeted for PCR-based diagnostic assays could result in either false negative or underquantitated viral load measurements. The TIB MOLBIOL LightMix® PCR assay is based on the amplification of a 175bp fragment of the small T-antigen with specific melting point of 64°C. We report three cases of immunosuppressed patients with hematologic malignancies that were monitored for BK virus in urine in which the real-time PCR assay rendered PCR products with melting temperature of 57°C that was significantly different from those described by the manufacturer. Sequencing of the PCR products obtained from the amplification of the T-antigen region using the following primers: BK1fw (5′-TGCCCAGCACACATGTGTCTA-3′) and ATSrev (5′-TTTTATCCTCGTCGCCCCT-3′) was done and showed polymorphisms in the T antigen gene (Fig. 1) one of which (G4471A) has never been described previously (Gene bank accession number KJ476629). Manna et al. have described clinical samples which yielded atypical amplification profiles, but the frequency with which this occurs is not clear from their data.3 Large and small T-antigen and anagnoprotein sequences are sometimes regarded as attractive sites for assay development since it seems to have the lowest rate of genome variability. However, it should be keep in mind that, at this time a few number sequences of these genes have known; so, it is also likely that additional gene polymorphisms will be discovered in these areas.4

The sequence obtained for VP1 region following the primers and conditions proposed by Li Jin et al.5 corresponded, in all cases, to the subtype VI (or Ib1 subgroup) that, according to epidemiological studies, has low rates in Europe showing the highest prevalence in the Southeast Asia, although it is widespread throughout the world.6 A recent study conducted by J. Ledesma in Spain reported that the subtype I was the predominant subtype detected in urine (61.2%) and plasma (38.2%) samples followed by subtype II and that the subtype found in urine can be different from that found in plasma.7

The abnormality of the RT-PCR results and, later, the polymorphisms found could indicate a common source of infection for the patients, likely from transfused blood products, since all of them have compatible blood groups and were transfused in the same period of time.