The incidence of cervical cancer in Spain is 8.6 new cases/100,000 women per year. Although it is one of the lowest in Europe, it causes in our country 848 deaths annually most of which could be prevented.1 There is not an organized population-based screening program in Spain. Each Autonomous Community offer a different approach, most of them opportunistic screening with cytology or a test for detection of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) in cervical samples. The recently published Guidelines for screening of cervical cancer in Spain, 20141 recommend the detection of HPV as the primary screening test due to its higher sensitivity and reproducibility over cytology.2

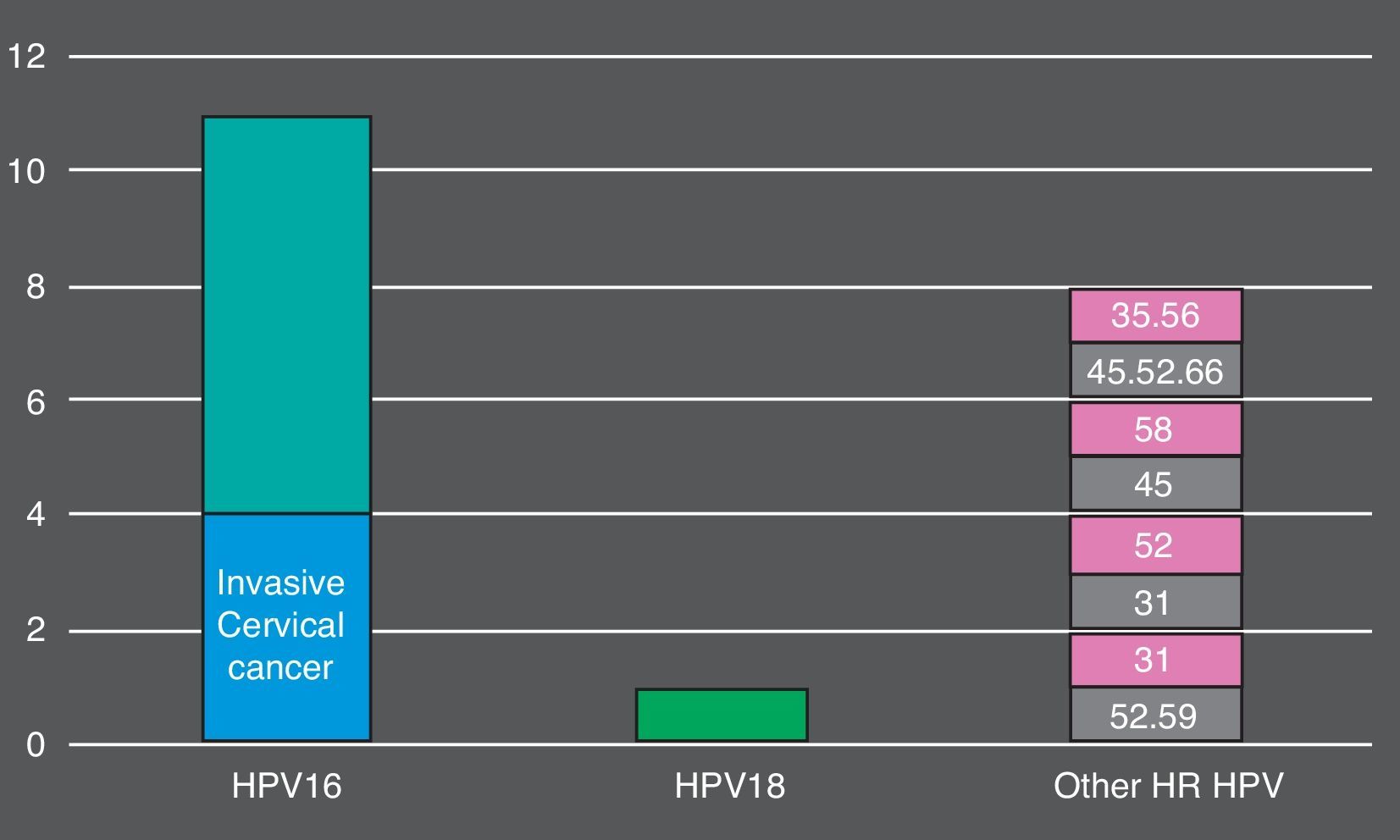

HPV genotypes 16 and 18 followed by genotypes 45, 31 and 35 account for 70% and 85% respectively of the cancer cases worldwide.2 It is important to know the distribution of genotypes in different geographical areas since some authors suggest that HPV genotypes 31, 33 and 45 may have similar risk of progression to HSIL+ lesions as HPV genotypes 16 and 18.3

The cobas® 4800 HPV Test (Roche Molecular Systems, Inc., Branchburg, NJ, USA) is an automated qualitative in vitro test for the detection of 14 high risk HPV genotypes (HR HPV). The test targets the highly conserved L1 region of the HPV genome using primer pairs directed to amplify 14 HR HPV; genotype-specific fluorescent oligonucleotide probes bind to polymorphic regions within the sequence amplified by these primers. The cobas® 4800 HPV Test identifies HPV16 and HPV18 genotypes separately, while simultaneously detecting 12 other HR HPV (HPV31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68) at clinically relevant infection levels.

In the present study we aimed to investigate the performance of cobas® 4800 against Linear Array HPV genotyping test® (Roche Diagnostics) and the genotype-specific distribution in cervical samples that resulted positive by cobas® 4800 in women with LSIL+ lesions undergoing opportunistic screening of cervical cancer in a Gynecological Unit in the metropolitan area of Madrid.

From June to September 2014, 141 cervical samples from 141 women with any positive result (HPV16, HPV18 or other HR HPVnon-16,18) by cobas® 4800 were studied. Negative samples by cobas® 4800 were not included in this study. Fully genotyping was further carried out using Liner Array HPV genotyping test. Cytology results were also investigated. The same vial (Thin Prep) was used for cytology and HPV detection by both methods.

Overall, 105 (74.5%) women who tested positive by cobas® 4800 had non-normal cytology. 26 (18.5%) had ASC-US, 59 (41.8%) had LSIL, 16 (11.3%) HSIL and 4 (2.8%) invasive cancer. The more prevalent HR HPV genotypes detected in HSIL+ lesions were: HPV16 (9, 56.2%), HPV45 (3, 18.7%), HPV52 (3, 18.7%) (Fig. 1). In total, cobas 4800 detected 41 out of 43 HPV16 and 8 out of 10 HPV18 detected by Linear Array (HPV16 was not detected in two samples with LSIL and ASCUS results and HPV18 was not detected in two samples with ASCUS and LSIL results). On the other hand, Linear Array did not detect two HPV16 (HSIL and LSIL cytology results) and two HPV18 in two samples (HSIL and normal cytology results).

There was an excellent correlation (agreement of 92%) in the detection of HPV16 or HPV18 between cobas® 4800 and Linear Array in the samples associated to LSIL+ lesions. It is well known that women infected with HPV16 or 18 have a very high 10-year cumulative absolute risk of CIN3+ compared with women infected with other HR HPV types.4 As stated in a previous study,2 cobas® 4800 showed a good performance for detection of HPV16 and 18. Interestingly in the present study 8 out of 20 HSIL+ samples contained other HR HPV types different to HPV16 and/or 18. In conclusion, our data show that HR HPV45, 31 and 52 play an important role in precancerous lesions and are detected frequently in the absence of HPV16 or 18 in the women included in this study. The value of specific genotyping HR HPV non-16,18 is controversial. Some Northern European and Japanese authors report that the risk for progression to HSIL+ in women infected with HPV31, 33 and 45 is similar to HPV16 and 18-infected women. According to this, Sanjose et al.5 considered that HPV45 (the third most common HR HPV globally) should also be included in type-specific screening protocols due to the early presentation of cases of invasive cervical cancer caused by this genotype. In the United States the risk of other HR HPV non-16,18 have not been investigated yet and therefore this risk remains to be stratified.3 Geographical differences in disease risk may exist and the utility of identifying these genotypes separately requires follow up studies in different areas of the world.