Metagenomics has decisively advanced the study of the gut microbiome, enabling a better understanding of its importance for human health. Metataxonomics, based on the sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene, provides taxonomic profiles of prokaryotes, while shotgun metagenomics allows a comprehensive characterization of all DNA present in a sample. With adequate sequencing depth, the latter increases taxonomic resolution to the strain level and provides detailed information on the functional potential of the microbiota. However, the lack of standardization in sample collection and processing, sequencing technologies, and data management limits the comparability of results and their implementation in clinical laboratories. This review offers a practical and updated framework on metagenomic methodologies, data analysis, and the application of artificial intelligence tools, highlighting advances and best practices to facilitate the integration of functional microbiome analysis into clinical practice and to overcome current challenges.

La metagenómica ha impulsado de manera decisiva el estudio del microbioma intestinal, lo que ha permitido comprender su importancia para la salud humana. La metataxonómica, basada en la secuenciación del gen del ARNr 16S, ofrece perfiles taxonómicos de procariotas, mientras que la metagenómica shotgun permite una caracterización más completa de todo el ADN presente en la muestra. Con una profundidad de secuenciación adecuada, esta última amplía la resolución taxonómica hasta el nivel de cepa y proporciona información detallada sobre el potencial funcional de la microbiota. Sin embargo, la falta de estandarización en la recolección y procesamiento de muestras, las tecnologías de secuenciación, y la interpretación y gestión de los datos, limita la comparación de resultados y su implementación en laboratorios clínicos. Esta revisión ofrece un marco práctico y actualizado sobre las metodologías metagenómicas, el análisis de datos y el uso de inteligencia artificial, destacando avances y buenas prácticas para facilitar su integración en la práctica médica y superar los desafíos actuales.

The human microbiota is the set of microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, protozoa and fungi, which cohabit in symbiosis at different locations in the human body with groups of stable and other variable species. Of the different specific microenvironments in the body, the most researched, thanks to the ease of studying it through faeces, is the gastrointestinal tract, in particular the gut microbiota. The concept of the microbiome is broader and includes the microbiota, its genomes and metabolites, and the conditions of the surrounding environment.

Historically, studies based on culture techniques have contributed to generating basic information on microorganisms, especially those related to infectious diseases. However, we now know that most intestinal microorganisms cannot be cultured in traditional culture media and conditions.1 Knowledge about the gut microbiome has been greatly boosted in recent years by the application of next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques.1 These massive studies of the microbiome have also helped us understand that the importance of the microbiome in relation to human health lies less in microbial composition than in how it functions.2 The gut microbiome is estimated to contain far more genes than the human genome,3 with different microbial species able to perform equivalent metabolic functions and the same species capable of performing different functions. It is therefore important that we analyse the functional properties of the microbiome and how these relate to those of the individual. All this highlights the need to make further progress in the field of Systems Biology, both to facilitate the integration of metadata from different sources (for example, host-related metadata) and optimise the design of metabolic models, in order to analyse the information in a biologically meaningful context. Recent years have seen the development of new analytical methods and computational tools, enabling a comprehensive analysis of the dataset related to the biological characteristics of the human microbiome. The data are derived from different omics approaches, including culturomics (use of multiple culture conditions combined with advanced microbial identification tools), metataxonomics (study of the composition and relative number of microorganisms), metagenomics (study of the composition and functions of the microbiota), metatranscriptomics (study of the gene expression of the microbiota), metaproteomics (study of protein synthesis by the microbiota) and metabolomics (study of the metabolites originating from the microbiota) (Fig. 1). The collection of all these data, and especially their subsequent analysis, is a complex and costly task, currently only possible in a few research laboratories. As yet, it has not been possible to include most healthcare laboratories, as this would require standardisation of processes and protocols and, in particular, the establishing of normal ranges. Hospitals would also have to hire bioinformatics personnel. Although laborious, these approaches are significantly expanding our knowledge of the gut microbiome and its potential preventive and therapeutic applications. However, they are yet to be introduced into hospital care settings.4

Methodological approaches to the study of the human gut microbiome. Gut microbiota from gastrointestinal/faecal samples can be analysed for a variety of purposes: (1) seeding of microorganisms on multiple media and appropriate culture protocols and mass isolation of microorganisms (culturomics); (2) extraction and sequencing of microbial DNA (metataxonomics and metagenomics); (3) extraction and sequencing of microbial mRNA (metatranscriptomics); and (4) extraction and analysis of microbial metabolites (metabolomics). These techniques require advanced computational tools and specialised laboratories, given the volume and complexity of the data generated.

Own creation from graphic resources available in BioRender.

A major constraint to conducting these studies is the standardisation of sample collection and extraction of genetic material. Both factors are essential to ensure comparability of results and inter-laboratory reproducibility of metagenomic studies. However, there are a number of challenges associated with this critical stage of analysis. The quality and composition of the extracted microbiome can vary considerably, due to factors such as the type of sample (for example, faecal, mucosal tissue, use of faecal swabs), the storage method, the time between collection and processing and the techniques used for DNA extraction. Studies have shown that freezing at -80°C and the use of DNA stabilisers, such as those in some commercial faecal collection tubes, are essential for minimising degradation of genetic material and unwanted bacterial growth.5 However, there are discrepancies about the use of these stabilisers, as they may affect the determination of other molecules in stool samples, such as metabolites.6,7 The efficiency of DNA extraction kits can differ significantly depending on their ability to lyse cells and release high-quality DNA, affecting both the extraction yield and how taxonomically representative the subsequent analysis will be.8 When standardising the process, it is also necessary to consider automating it, avoiding laborious and person-dependent processes, in order to facilitate implementation in a clinical laboratory.

In addition, the lack of standardised protocols introduces bias in microbiome profiling, as differences in extraction and storage techniques may result in the loss of specific taxa, particularly under-represented ones, or the overestimation of the most abundant ones. Such bias also limits the possibility of reliable comparisons between studies or laboratories.9 Moreover, technical variability affects the reproducibility of results, particularly in longitudinal or multicentre studies. Establishing standardised consensus protocols for sample collection, storage and processing is therefore seen as a key step towards more robust and comparable scientific metagenomic analysis.

The rise of metataxonomics or phylogenetic metagenomicsApproaches based on sequencing DNA extracted from complex microbial communities have represented a paradigm shift in the study of the gut microbiome. Initially, the taxonomic profile of microbial communities was obtained by sequencing amplicons of one or more genes considered as phylogenetic markers (metataxonomics), such as the gene encoding the 16S subunit of the bacterial ribosome (16S rRNA gene) for prokaryotes and the gene encoding the 18S subunit in the case of eukaryotic microorganisms (18S rRNA gene). In addition, in eukaryotes, internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions, located between the large and small subunits of ribosomal genes, are often used as markers to differentiate species at higher resolution. Amplification and sequencing of these regions makes it possible to create a taxonomic profile of the community. Sequencing reads are subjected to a set of filtering steps with the aim of reducing technical artefacts which include the aggregation of near-identical reads. Aggregation can be done by grouping sequences with a certain similarity value (95–99% identity), generating an operational taxonomic unit (OTU), or by creating amplicon sequence variants (ASV), which provide a higher level of resolution.10 Subsequently, bioinformatics tools and programmes such as DADA211 or QIIME212 enable the taxonomic assignment of the sequences by comparing them with those deposited in databases such as SILVA,13 Greengenes214 and RefSeq.15 Although amplicon sequencing only provides taxonomic information on the microbial community, there are now bioinformatics tools which enable functional inferences to be made, such as PICRUSt216 and Tax4Fun2,17 and predict the functional composition of a microbial community using a database of reference genomes.

Sequencing of 16S rRNA gene amplicons is the most commonly used method in microbiota studies. However, it has significant limitations; it does not enable the detection of viruses or eukaryotic micro-organisms, as they lack such a gene, and nor does it provide direct information on the actual genomic content. In addition, the number of ribosomal operons varies between species and even between strains, making it impossible to accurately estimate the relative abundance of a microorganism based on the number of 16S rRNA gene reads alone. These limitations, along with the fact that only compositional profile information is provided, were the push behind the development of large-scale sequencing (Table 1). The choice of approach depends on the objectives of the study, the available budget and the analytical infrastructure. In general, metataxonomics may be more suitable for exploratory studies, while shotgun metagenomics is preferred for integrated or functional studies.

Comparison and main differences between metagenomic approaches.

| Characteristic | Metataxonomics | Shotgun metagenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Main purpose | Taxonomic profiling based on specific marker genes | Complete profile of genomic content and functionality |

| Target gene | Specific regions such as 16S rRNA gene (bacteria/archaea) or ITS (fungi) | All DNA present in the sample |

| Taxonomic resolution | Generally down to gender level | Up to species or strain level, depending on the sequencing depth |

| Functional analysis | Indirect inference (for example, PICRUSt2 for functional predictions) | Direct analysis based on identified functional genes |

| Coverage of microorganisms | Dependent on the selected gene. Mainly bacteria and archaea; limited for fungi and viruses | Bacteria, archaea, fungi, viruses and other eukaryotes |

| Analytical tools | QIIME2, DADA2, Mothur | MetaPhlAn4, strainPhlAn, HUMAnN3, Kraken2, MEGAHIT |

| Computational cost and resources | Lower computational cost and requirements | More expensive and computationally demanding |

| Main applications | Ecological and microbiota studies, more basic, quick analyses | Functionality studies, genome reconstruction (MAG), antibiotic resistance genes |

| Limitations | Low taxonomic and functional resolution; inability to detect microorganisms without marker genes | Analytical complexity and costs associated with sequencing and analysis. Bioinformatics staff are needed |

MAG: metagenome-assembled genomes.

Shotgun sequencing of metagenomes has become the method of choice for studying and classifying microorganisms from diverse ecosystems. The constant improvement in quality and cost-effectiveness, especially the lowering of costs, makes it an increasingly easy, fast and affordable technique in terms of cost and handling.

The aim of shotgun metagenomics is the untargeted sequencing of all genomes present in a sample, allowing higher resolution profiling and the study of gene content and functional profile.18 This analysis can be carried out from two different approaches.

Firstly, de novo assembly attempts to reconstruct genomes from DNA fragments.19 There are tools for this that group sequences into larger units or contigs, such as SPAdes20 or MEGAHIT21. These assemblies are compared in reference databases and enable functional and taxonomic annotation. However, contigs can also be grouped into assemblies from the same organism using binning methods, and subsequently reconstruct assembled genomes from metagenomes (metagenome-assembled genomes [MAG]).22 This approach enables detailed analysis of the functions and metabolism of microorganisms and more in-depth study of their complex interactions. It also makes it possible to obtain genomes of unknown microorganisms, but only if they have adequate coverage to be assembled. However, it involves a high computational cost due to assembly, mapping and binning.18 In addition, metagenomic assembly poses a number of challenges and is not universally applicable.23 For example, it is not suitable for low-abundance genomes or when there are different strains within the same bacterial species.

The second computational approach allows the identification of the taxonomic composition and functional profile of sequencing reads by mapping them to reference microbial genome or protein family databases.19 For this approach, tools such as MetaPhlAn4,24 which allows the determination of microbial composition at species level, and HUMAnN3,25 which performs functional analysis, are usually used. These methods mitigate assembly problems, increase computational speed and detect microorganisms with low abundance.18

Most methods used for gut microbiome profiling are limited to the species level. However, there is considerable variation within species, so there is a growing interest in analysis at the strain level. Tools have now been developed to detect the strains present in a sample by means of shotgun metagenomics. One example is StrainPhlAn,26 which identifies the dominant strain of a given species in each sample. Once again, this is highly dependent on all sequences being deposited in public databases, but this makes it possible to identify specific strains which are spread across several countries, or associated with a particular disease. For example, shotgun metagenomics has identified Escherichia coli (E. coli) O157:H7 and Klebsiella pneumoniae UCI 34, strains associated with patients with recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection,27 and the E. coli ST131 clone, which is the main cause of urinary tract infections worldwide and is specifically associated with resistance to many of the antimicrobials used in this disease.28

The virome is an important component of microbial communities, making its characterisation fundamental to understanding this ecosystem. Although virus identification from metagenomes has been performed for some time, previous strategies required the assembly of sequences into contigs and the subsequent identification of viral sequences within the contigs. In recent years, improved databases of intestinal viruses have emerged, such as the Metagenomic Gut Virus (MGV) catalogue,29 which has facilitated the development of tools capable of profiling their content, such as Phanta.30 There are also numerous challenges in characterising the intestinal microbiome. Although specific tools exist, such as FunOMIC,31 MiCoP32 and HumanMycobiomeScan,33 their robustness is currently limited, largely due to the lack of comprehensive and up-to-date reference databases.34

Up to now, metagenomic studies have mainly been performed using second-generation sequencing systems, such as Illumina or Ion Torrent, which only allow sequencing of short DNA fragments, usually of around 300 base pairs. Sequencing of long DNA fragments has certain advantages, especially for sequence assembly. The accuracy of third-generation sequencing technologies, such as PacBio and Oxford Nanopore, has significantly improved and their cost decreased, meaning they are now are increasingly used in the study of the gut microbiome.35 Both technologies are characterised by reading long fragments of DNA, which can end up having the bacterial chromosome in two or two contigs. A combination of the two technologies is already being applied in clinical laboratories for the identification and analysis of occasional, generally rare pathogens, such as the SARS-CoV-2 virus.36 The strategy is based on combining a technology that provides short reads, with few sequencing errors, with another technology that provides long reads, although the one with long reads may contain more errors. Many healthcare laboratories incorporated sequencing platforms with the COVID-19 pandemic which are now being used for other microorganisms, and which will undoubtedly be of great help in advancing the fight against antibiotic resistance by detecting the genetic mechanisms involved.

The analysis of metagenomic data is usually performed using command-line based tools, which requires a high level of expertise in bioinformatics. Among other reasons, this is due to the fact that a large number of files are usually handled, making it advisable to automate repetitive tasks through scripts; that in many cases a high computing capacity is required, usually accessible through command-line servers; and that this environment allows for greater customisation of analyses and the use of advanced tools.37 However, graphical interface platforms have been developed, such as MicrobiomeAnalyst (https://www.microbiomeanalyst.ca/), which significantly simplify the process. These tools make the analysis more accessible to users with limited bioinformatics knowledge, although the ability to customise them is limited, which may render them less useful in more complex or specific studies.

As a complementary approach to address the technical challenges in microbiome analysis, shallow shotgun sequencing (SS) has also been proposed as an efficient alternative to traditional methods such as 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing and deep metagenomic sequencing.38 This technique, which uses sequencing depths between 2 and 5 million reads per sample, has less technical variability than 16S rRNA gene sequencing at different experimental steps, such as library preparation, and shows much higher resolution, overcoming the limitations of the 16S rRNA gene to classify only at the genus level in most cases, while allowing direct functional characterisation of the microbiome by profiling specific genes.38

Limitations and challenges in the application of metataxonomics and metagenomics in clinical practiceDespite the important advances described in the previous section, metagenomic analysis continues to face multiple challenges (Table 2). On the one hand, data quality and microbiome profiling are conditioned by experimental, biological and environmental factors. Among the most relevant are the type of sample collected and the procedure or kit used, the preservation method and the sequencing technique and platform used. For example, differences in microbial composition have been reported between whole faecal samples and rectal swabs.39 For storage, immediate storage at -80°C is considered the reference standard, although commercial buffers, such as OMNIgene GUT or Zymo DNA/RNA Shield, have been shown to be suitable for preserving the stability of the microbiome at room temperature.40–42 Another important aspect is the maintenance of anaerobic conditions after collection, as exposure to oxygen can significantly alter the microbial profile.43 In addition, DNA extraction protocols have a significant influence on microbial representation, and it is essential to include a mechanical disruption step.42,44 Lastly, the sequencing technique (amplicon sequencing or shotgun sequencing), the platform used and the library preparation protocol may introduce significant bias in the results obtained.45

Critical points in the microbiome analysis workflow where inter-study variability limits comparability and interpretation.

| Step | Critical points |

|---|---|

| Collection, preservation and processing | Type of sample (whole stool, dry swab, spatula, etc) |

| Collection method and kit (OMNIgene, Zymo DNA/RNA Shield, etc) | |

| Time between collection and freezing/extraction | |

| Storage and transport conditions (temperature, freeze-thaw cycles, anaerobiosis) | |

| Inclusion of key metadata (gender, age, diet, medication, BMI, etc) | |

| Seasonal and intra-individual variability | |

| DNA extraction | Faecal microbial load (Bristol scale) |

| Method of lysis (chemical vs mechanical) | |

| Extraction kit used (and sample-to-sample consistency) | |

| Inclusion of blanks and positive controls | |

| DNA yield and purity | |

| Centralisation of the process to avoid variations between laboratories | |

| Sequencing | Sequencing type (16S vs shotgun metagenomics) |

| Sequencing platform used (Illumina, Nanopore, etc) | |

| Library preparation | |

| Sequencing depth | |

| Cost and availability | |

| Amplification bias or insufficient coverage | |

| Cross-contamination and misassigned index ("index hopping") | |

| Read pre-processing | Quality control (FastQC, Trimmomatic, etc) |

| Batch effect correction (ComBat, Bayesian models, etc) | |

| Contaminant removal (Squeegee, MicrobIEM, etc) | |

| Assembly vs mapping (MEGAHIT, MetaPhlAn, etc) | |

| Inclusion and interpretation of negative and positive controls | |

| Taxonomic and functional assignment | Tool used (QIIME2, DADA2, Kraken2, MetaPhlAn, HUMAnN3, etc) |

| Taxonomic database (Greengenes, SILVA, ChocoPhlAn, GTDB, etc) | |

| Functional annotation database (KEGG, MetaCyc, etc) | |

| Taxonomic resolution achieved (genus vs species vs strain) | |

| Inferred functional capability (prediction vs metagenomics) | |

| Database versions and updates | |

| Possibility of identifying new microorganisms | |

| Data post-processing | Abundance and prevalence filter applied |

| Normalisation method (CPM, CLR, TSS, etc) | |

| Impact of "sparsity" (high presence of zeros) | |

| Dimensionality reduction methods | |

| Statistical and clinical analysis | Approaches applied (diversity, differential abundance, networks, clustering, etc) |

| Correction for confounding factors (diet, antibiotics, exercise, etc) | |

| Statistical technique (linear, mixed models, PERMANOVA, etc) | |

| Interpretation of results in clinical settings | |

| Integration with other omics (metabolomics, transcriptomics, etc) | |

| Application of artificial intelligence and machine learning models | |

| Limitations for causal inferences |

There is also a need for standardisation in the data analysis and processing stages. Methodological variability arising from differences in sequence filtering, clustering, taxonomic assignment and binning, due to the use of different bioinformatics tools and workflows, introduces analytical and statistical bias. This heterogeneity represents a barrier to reproducibility and comparability between studies.46 Multiple metagenomic analysis protocols were recently compared between different laboratories, showing considerable variability in results, even when processing the same samples under controlled conditions.47

In this context, it is particularly important to note that there are still no standardised and validated protocols available for the routine assessment of human gut microbiota in the clinical setting. Although both 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomics allow the determination of the composition and abundance of taxa present in a sample, the lack of standardisation limits their applicability. The lack of validated tools and clinically relevant biomarkers prevents systematic comparisons of human microbial communities between different locations or the establishment of robust associations with specific diseases, which is one of the main challenges in this field.48

It is important to highlight that there are currently no standardised and validated protocols for the routine assessment of human gut microbiota in the clinical setting. Both 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing and the shotgun approach enable the composition and abundance of each taxon in a sample to be determined in order to characterise the microbiome, with the limitation that the process has not been standardised. This lack of validated tools and suitable biomarkers prevents a more comprehensive comparison of human microbial communities of different locations or their association with a given disease, which is one of the main challenges in this field.48

In this respect, the choice of reference database is also a critical aspect which can significantly influence the results of gut microbiome analysis. In the case of metataxonomy, databases such as SILVA,13 Greengenes214 and RefSeq15 differ in their taxonomic coverage, update frequency and annotation criteria, which can lead to substantial discrepancies in the profiles obtained from the same data.49 In shotgun metagenomics, accurate identification is even more dependent on the availability of complete genomes in databases such as RefSeq15 and the Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB)50 or, more specifically for the human gut microbiome, the Unified Human Gastrointestinal Genome (UHGG)51 or ChocoPhlAn.25 The variability in the databases used and their constant updates are therefore an important source of heterogeneity between studies, underlining the need to agree on standards and use specialised resources according to the study objective and ecosystem. In addition, a large proportion of sequences obtained in metagenomic studies remain unmatched by known entries, limiting our ability to interpret the metabolic and clinical potential of the microbiome. In this context, the term "functional dark matter" refers to the large amount of genomic and functional information that remains unknown or uncharacterised in microbial communities because it has no known equivalents in previously studied organisms.52 This includes genomic sequences which have no detectable similarity to those present in available reference genomes. Pavlopoulos et al. (2023) recently shed light on this dark matter using a computational approach which avoids relying on reference databases.52 By analysing more than 26,000 metagenomes, the authors identified more than a thousand million protein sequences with no known similarities in existing databases, resulting in the creation of over 100,000 novel metagenome protein families (NMPF), demonstrating the magnitude of functional diversity that remains unexplored.

When introducing the study of microbiota in a healthcare laboratory, it is always necessary to standardise processes, automate them and, above all, establish cut-off points to define normality. We need to be aware that a "normal" or "healthy" microbiota has yet to be defined due to the high individual variability in both health and disease conditions. In this context, although the inclusion of positive and negative controls is essential, their implementation is particularly complex due to the nature of the field and the difficulties associated with correct interpretation.53 A rethink is also needed on the use of faeces as a universal sample for the study of gut microbiota. Faeces do contain the microorganisms which are released into the intestinal lumen, but we are becoming increasingly certain that the organisation of ecosystems has a characteristic spatial distribution. The microbiota of the small intestine differs from that of the large intestine, and there are even different sections according to the environmental conditions.54 These niches appear to be difficult to access, and as previously mentioned, functionality is more important than composition, but perhaps we should start assessing the passage of microbial metabolites into blood, with potential systemic effect, rather than, or at least as a complement to, studying them in faeces. Despite efforts to establish a regulatory framework to guide appropriate use and promote evidence-based development of microbiome testing, there are still significant knowledge gaps and limitations which need to be addressed, in order to pave the way for clinical implementation of these tests.4

Statistical methods for microbiome analysis and mass data analysisApart from the challenges inherent to metagenomic techniques, some elements of the analysis of data deriving from microbiome testing pose significant challenges in terms of methodology. This type of data is characterised by overdispersion, meaning that the abundance of features (i.e. microorganisms, metabolic pathways, etc) is highly variable: high dimensionality, with potentially thousands of features profiled; and wide dispersion with a high presence of zeros in the abundance matrix, often up to 90%. In particular, this dispersion occurs because many species are present in low abundance and are below the detection threshold of the sequencing method (technical zeros), or because they are completely absent in the sample (biological zeros).55,56 The combination of these three characteristics complicates statistical analysis and subsequent interpretation.

Focusing on metagenomic data, prior to statistical analysis, the raw data are subjected to additional filtering in order to reduce noise. In this step, features with low abundance (for example, <500 counts) and prevalence (for example, <10% of samples) are filtered out. The taxonomic level can also be chosen, considering that going down to the species level entails a significant inflation of zeros.57 In addition, it is important to take into account heterogeneity and variability between samples, so normalisation of count data is essential to mitigate these variations and improve comparability. Normalisation is a necessary transformation in order to perform a robust analysis, which takes into account the peculiarities of the microbiome data and the technical variability inherent in sequencing technology.58,59 The most commonly used methods include Total Sum Scaling (TSS), Cumulative Sum Scaling (CSS), Relative Log Expression (RLE), Aitchison's Log-Ratio (ALR), Aitchison's Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) and Counts Per Million (CPM), and the choice will depend on the nature of the data, the sequencing technology applied and the subsequent analytical approach to the results.60

There are three main approaches to the study of the microbiome,55 the aim of which is to detect and quantify:

- 1

Taxa differentially abundant between phenotype groups (differential abundance analysis)

- 2

Associations between taxa and covariates (integrative analysis)

- 3

Associations between taxa across the microbiome network (network analysis)

The method for detecting differentially abundant taxa between phenotype groups is known as differential abundance analysis. This analytical technique provides insight into the relationship between symbiotic microorganisms and human health, and it identifies microbial biomarkers for disease detection. There are numerous methods, each with its own statistical motivations. For example, edgeR61 arose from the need to separate biological variability from the technique to reduce bias when looking for phenotypic differences attributed to the abundance of RNA-Seq data. DESeq262 seeks a model which can account for the presence of outliers and small replicate sizes while producing interpretable results. Dispersion and zero-inflation are factors on which some methods such as metagenomeSeq,63 Zero-Inflated Beta model (ZIBSeq)64 and Zero-Inflated Generalised Dirichlet-Multinomial model (ZIGDM)65 focus on. Analysis Composition of Microbiome (ANCOM)66 arose from the need for models which could also consider the compositional nature of count data. In addition, ZIGDM takes into account the correlation structure and dispersion patterns amongst features. Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect Size (LEfSe)67 determines which features are most likely to explain differences between groups by combining standard tests of statistical significance with additional tests that code for biological consistency and significance of effect for each characteristic.

While the above methods enable the analysis of groups of interest and the identification of features associated with each one, it is crucial to consider the multiple covariates that may be involved, such as metabolites, antibiotic use, and environmental and genetic factors. Rigorous collection of metadata, such as habitual diet, medication use and metabolites, is essential for properly interpreting results and controlling for potential confounding variables. For this reason, integrative analysis methods have emerged which aim to identify and quantify associations between the microbiome and different covariates/metadata.55 These methods provide a more complete picture of the interactions between microorganisms and human health.

The mixOmics68 package contains numerous tools for multivariate analysis focused on the exploration and reduction of data dimensions and the visualisation of results. Meanwhile, mixMC69 allows both compositional data and numerous variables of interest to be included in the analysis. It also has tools which enable the integration of two or more different data sets measured on the same samples, such as Data Integration Analysis for Biomarker Discovery using Latent Components (DIABLO),70 and sets of the same variables measured on different samples, such as Multivariate Integrative Method (MINT).71 They use statistical multivariate analysis techniques, such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Projection to Latent Structures-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) regression to select the features that most discriminate between groups.

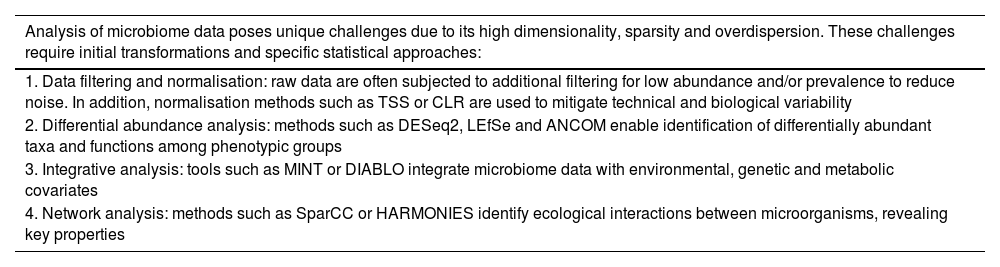

Microbial ecological interactions affect microbiome function and host health through the formation of complex communities with symbiotic relationships where microorganisms coexist. The goal of network analysis is to construct microbiome networks that characterise microbial ecological associations, which can help uncover fundamental properties and mechanisms of microbial ecosystems.55 Graph models consist of nodes and edges which are used to visualise the estimated microbial network. Each node corresponds to a taxon and an existing edge represents a direct association between any two nodes. Current statistical methods for network analysis estimate the correlation structure, such as Sparse Correlations for Compositional data (SparCC)72 or partial correlation, such as Hybrid Approach foR MicrobiOme Network Inferences via Exploiting Sparsity (HARMONIES),73 of normalised count data to construct a network of nodes and edges (Table 3).

Statistical methods for the analysis of the microbiome.

| Analysis of microbiome data poses unique challenges due to its high dimensionality, sparsity and overdispersion. These challenges require initial transformations and specific statistical approaches: |

|---|

| 1. Data filtering and normalisation: raw data are often subjected to additional filtering for low abundance and/or prevalence to reduce noise. In addition, normalisation methods such as TSS or CLR are used to mitigate technical and biological variability |

| 2. Differential abundance analysis: methods such as DESeq2, LEfSe and ANCOM enable identification of differentially abundant taxa and functions among phenotypic groups |

| 3. Integrative analysis: tools such as MINT or DIABLO integrate microbiome data with environmental, genetic and metabolic covariates |

| 4. Network analysis: methods such as SparCC or HARMONIES identify ecological interactions between microorganisms, revealing key properties |

Classic statistical methods have been replaced by more sophisticated methods, such as artificial intelligence (AI) tools. AI and, in particular, machine learning (ML) and deep learning are opening up new frontiers in microbiome research (Table 4). The use of these tools can improve the understanding, diagnosis and treatment of diseases associated with the human microbiome.74 AI makes it possible to analyse complex and large datasets by identifying patterns and associations limited in other traditional statistical methods. It also facilitates the analysis of metagenomic data, improving the identification and classification of microbial species. These tools can be used to design predictive models and improve the diagnostic accuracy of some microbiome-associated diseases. In addition, they can contribute to personalised treatments by improving knowledge of individual profiles. Although it requires a larger amount of robust and comparable data than microbiota studies usually have, the implementation of standards in metagenomic data collection and analysis, such as those proposed by projects like the American Gut Project (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/metagenomics/studies/MGYS00000596#overview), facilitates the generation of high quality data for training predictive models.75

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning.

| The use of AI and machine learning has revolutionised microbiome analysis, facilitating the detection of complex patterns and the development of predictive models. Common applications include: |

|---|

| Unsupervised ML: techniques such as hierarchical clustering and PCA to identify data structures and patterns |

| Supervised ML: methods such as RF and SVM for classifying and predicting host features |

| These tools are transforming the field towards identifying biomarkers, personalising treatments and developing preventive interventions. However, challenges remain related to data quality, standardisation of protocols and ethical management of AI |

ML is a subset of AI methods used to recognise, classify and predict patterns. In microbiome research, ML has been applied to tasks such as predicting host phenotype, classifying microbial characteristics (i.e. determining the abundance, diversity or distribution of the microbiota), studying the complex physico-chemical interactions between the components of the microbiome, and monitoring changes in its composition.74,76 ML models can be trained to predict the composition of microbial communities as a function of various input factors, such as host genetics, diet and environmental factors, which can help us understand the factors that influence microbial composition and its relationship to human health.57

Data analysis using ML can be approached from two main perspectives. Unsupervised ML methods attempt to look for patterns in data sets without known dependent variables or labels. These techniques allow for two different approaches: clustering and dimensionality reduction.77 Clustering techniques organise samples into groups based on measures of similarity. These include hierarchical clustering, which constructs a hierarchy by combining or dividing groups according to a measure of dissimilarity, and k-means clustering, which divides the data into a predetermined number of groups, denoted as k, assigning each observation to a group according to its distance from the centre of that group.78 These tools have led to the identification of novel patterns in the study of the gut microbiome, such as the discovery of enterotypes or co-abundance gene clusters.79 Dimensionality reduction techniques make it possible to represent data with high dimensionality (i.e. with a large number of variables) by extracting the most relevant variables. These include PCA, based on a covariance matrix and Euclidean distance, and Principal Coordinate Analysis, which uses other dissimilarity metrics, such as those applied in the analysis of ®-diversity.77

Unsupervised ML methods are useful exploratory tools for examining data to determine important data structures and patterns of correlation.78 However, supervised ML methods are more commonly used in host trait prediction. A model is first trained on input data or features (independent variables) supplemented with dependent variables or labels indicating the results for the input samples. The generated model is potentially able to predict the results of new samples. When the dependent variables are categorical, the ML model can be used in classification tasks, while, if they are continuous numerical, they can perform regression tasks.79 Among the most commonly used supervised ML models in microbiome analysis are regression models (linear or logistic), Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machines and neural networks.80 In particular, ensemble learning methods based on decision trees, such as RF, have been widely applied in studies on the gut microbiome.79,81

Numerous statistical tools are currently available for the study of the microbiome. However, the initial transformations and the choice of statistical method depend to a large extent on the available data and the specific objectives of the study. The microbiome field is also evolving from the identification of associations towards the search for causality and prediction, and ML tools will play a crucial role in this transition. In order to promote research and work on the identification of predictive and discriminatory "omics" features, it is necessary to improve repeatability and comparability, develop automation procedures and define priority areas for the development of new machine learning methods targeting the microbiome.82 However, while the potential for the application of AI in microbiota research is extraordinary, there are also important challenges related to quality and normalisation, improving algorithms so they can better handle the variability and complexity of microbiome data, combining them with other genomic, proteomic and metabolomic data, and ensuring its ethical use in research.83

Conclusions and future perspectives in the study of the gut microbiomeThe study of the gut microbiome has advanced significantly, thanks to next-generation sequencing technologies and bioinformatics tools. However, it still faces critical challenges which limit its full potential, especially in clinical applications and in areas such as nutrition and health. The absence of standardised protocols for sample collection, storage, extraction and analysis introduces a high technical variability which hinders reproducibility of studies and comparability between laboratories. The implementation of international guidelines that harmonise these procedures is imperative to overcome these barriers and build a solid foundation for the development of biomedical applications, particularly in the design of personalised interventions and prevention strategies based on the modulation of the microbiome.

Despite these limitations, advances in multi-omics data integration and the use of technologies such as AI and machine learning are transforming the way we approach the microbiome. These tools not only enable the identification of complex patterns, but also facilitate the prediction of microbiome-host interactions and the identification of key biomarkers. In the clinical setting, these innovations open up new possibilities, such as personalisation based on the individual microbiome profile, the identification of dietary components, drugs and therapies that modulate the microbiome, and the design of targeted therapeutic strategies.

Standardisation of procedures for microbiome analysis is essential for researchers and practitioners to confidently interpret results over time, as well as to facilitate comparisons between individuals in the same study or cohort. This article presents the main critical points in the workflow related to the analysis and management of gut microbiome-related data where standardisation is necessary (Fig. 2). The complexity of microbiological data also poses significant challenges, such as the need to improve the functional interpretation of genomic dark matter and to ensure the quality of data used in AI algorithms. Addressing these limitations will be essential if the gut microbiome is to become a central tool in disease prevention and treatment. It will also help consolidate its role in the next generation of therapies, public health strategies and innovative approaches to promote healthy ageing and the reduction of lifestyle-related chronic diseases.

At the same time, the ethical handling of data generated in the study of the microbiome is becoming increasingly important. There is a need to ensure privacy and security of data and to ensure equitable access to its applications in health. Creating regulatory frameworks which integrate these considerations will be key to building public confidence and maximising the positive impact of the microbiome on overall health.

Lastly, interdisciplinary collaboration and data exchange between researchers, institutions and countries will be essential to accelerate the development of new clinical and nutritional applications. Only through a comprehensive and coordinated approach will it be possible to overcome current challenges and take full advantage of the opportunities offered by the study of the microbiome for improving human health.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors are grateful for the funding received from the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (MICIN) [Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities] (Project PID2023-148419OB-I00, MICIN). We are grateful for the support of the Red Científica Conexión [Scientific Network Connection]-MICROBIOMA, funded by the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC) [Spanish National Research Council], as well as the MIDAS Network (RED2022-134934-T) funded by MICIN.