To compare sexual practices and risk behaviours between MSM who were first diagnosed with hepatitis C (HCV) in the previous 12 months and those who were never diagnosed; and, to identify factors associated with a diagnosis of HCV.

MethodsThe European-MSM-Internet-Survey (EMIS) was implemented for 3 months during 2010, mainly on websites for MSM. Data on socio-demographic characteristics, sexual behaviour, drug use, STI history, and other sexual health variables were collected. The Chi-square test and logistic regression analysis were used to analyse the data.

ResultsData from 13,111 respondents were analysed. The proportion of MSM who had ever been diagnosed with HCV infection was 1.9% (n=250), and of those currently infected with the virus was 0.6% (n=78). The percentage of those first diagnosed in the last 12 months was 0.4% (n=46), of whom 70% were HIV-negative and 22% had HIV coinfection. Having a first diagnosis of HCV in the last 12 months was more common among HIV-positive than among HIV-negative MSM (0.9% vs 0.4%) and among MSM born abroad than among Spanish-born (0.7% vs 0.3%). MSM diagnosed with HCV in the last 12 months were more likely to have had: more than 10 sexual partners, sex abroad, receptive anal intercourse, insertive/receptive fisting, and unprotected anal intercourse with non-steady partners of unknown or discordant HIV-status. Likewise, they reported more frequent visits to sex-focused venues, higher drug use, as well as a higher proportion of STI diagnosis. In the multivariate model, visiting a public sex-focused venue, practicing receptive fisting, using erection enhancing medication and having a diagnosis of syphilis were independently associated with a first diagnosis of HCV in the last 12 months.

ConclusionsHCV infection does not seem to be restricted to HIV-infected MSM. Certain sexual behaviour (fisting, visiting sex-focused venues), drug use, and ulcerative STI seem to be associated with a diagnosis of HCV.

Comparar las prácticas sexuales y otras conductas de riesgo entre los HSH diagnosticados por primera vez con el virus de la hepatitis C (VHC) en los últimos 12 meses y los nunca diagnosticados; y, determinar factores asociados al diagnóstico del VHC.

MétodoLa European MSM Internet Survey (EMIS) fue implementada en el 2010, durante 3 meses, principalmente en páginas de contacto gay. Se recogió información sobre conductas sexuales de riesgo, consumo de drogas, historia de ITS, prevalencia del VIH, entre otros temas. Para analizar los datos se utilizó la prueba chi-cuadrado y análisis de regresión logística.

ResultadosDatos de 13.111 participantes fueron analizados. El 1,9% de la muestra (n=250) había recibido un diagnóstico del VHC, el 0,6% (n=78) estaba actualmente infectado y un 0,4% (n=46) recibió por primera vez su diagnóstico en los últimos 12 meses. Entre estos últimos, el 70% fueron VIH-negativos y el 22% tenía coinfección con el VIH. Tener un primer diagnóstico del VHC en los últimos 12 meses fue más común entre VIH-positivos que entre VIH-negativos (0,9% frente a 0,4%) y entre extranjeros que entre españoles (0,7% frente a 0,3%). En una significativa proporción (p<0,05), los HSH diagnosticados del VHC en los últimos 12 meses tuvieron más: parejas sexuales, sexo en el extranjero, penetración anal receptiva, fisting insertivo/receptivo y penetración anal sin condón con parejas sexuales ocasionales de seroestatus desconocido o discordante frente al VIH. Asimismo indicaron frecuentar más locales de sexo, alto consumo de drogas y tener una mayor proporción de diagnóstico de otras ITS. En el modelo multivariado, visitar un local de sexo público, practicar fisting receptivo, tomar medicamentos para la disfunción eréctil y tener un diagnóstico de sífilis estuvieron independientemente asociados con un primer diagnóstico del VHC en los últimos 12 meses.

ConclusionesLa infección del VHC no parece ser restrictiva a los HSH VIH-positivos. Algunas conductas sexuales (fisting, visitar locales donde se practica sexo), el consumo de drogas y las ITS ulcerativas parecen estar asociadas a un diagnóstico del VHC.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has emerged as a sexually transmitted infection (STI) among men who have sex with men (MSM) over the past decade,1 and since 2000 HCV outbreaks among HIV-infected MSM have been recognised in Europe. The HCV epidemic was originally reported in western European countries (England, the Netherlands, and France).2 HIV/HCV coinfection is more likely to be in MSM.3,4 In a Swiss cohort of HIV-positive people, HCV incidence increased 18-fold in MSM in the last 13 years.5 HIV-positive MSM have approximately four times more risk of acquiring HCV6 and having lower CD4 T-cell counts increase the risk of HCV infection.7 Phylogenetic analyses suggest networks of transmission among HIV-positive MSM.8 From a behavioural perspective, serosorting could have created selective “high-risk” sexual networks for STI transmission, that further fuel the spread of HCV within the group of HIV-positive MSM. Alternatively, it is plausible that HIV is transmitted more efficiently sexually compared to HCV, and hence will precede HCV infection in the majority of MSM who engage in high-risk sexual behaviour.9

Outbreaks of HCV in HIV-negative MSM in cities of high-income countries have not been detected. However, it is unclear whether the increasing HCV incidence is occurring exclusively among HIV-positive MSM or whether this apparent exclusivity simply reflects a lack of data from HIV-negative MSM. This could be due to lower rates of risk behaviours and fewer intersections with health care in HIV-negative MSM, but it is also highly likely that HIV independently confers a greater likelihood of transmucosal HCV acquisition.10 In general, regular HCV screening is not recommended for MSM without HIV infection, and unlike HIV-infected MSM, these individuals are unlikely to have the opportunity for HCV infection to be suspected on the basis of results of routine liver function tests.11

In 2010, the first acute HCV outbreak among HIV-infected MSM was reported in Spain.12 Before that year, epidemiology of HCV did not include MSM.13,14 Until now, no study in Spain has specifically focused on HCV infection among all MSM. The objectives of this analysis, based on Spanish data from the European MSM Internet Survey (EMIS),15 were to compare sexual practices and other risk behaviours between MSM reporting their first diagnosis of HCV in the last 12 months and those who were never diagnosed; and, to analyse factors associated with a first diagnosis of HCV in the last 12 months.

MethodsParticipantsA total of 13,753 participants completed the survey during June and August of 2010. The inclusion criteria were: males; living in Spain; at or over the age of sexual consent in Spain (13 years old); sexual attraction to men and/or had sex with men; indicating having understood the nature and purpose of the study; and consent to take part. After excluding cases that did not fulfil the inclusion criteria or with inconsistent data, the final sample was of 13,111 men. A detailed description of the Spanish sample can be found in the Spanish EMIS report which has already been published.16

InstrumentThe EMIS questionnaire was based on previous questionnaires (pre-existing national or regional questionnaires targeting MSM), internationally agreed indicators, scientific literature, and feedback from EMIS network partners. The questionnaire was available simultaneously in 25 European languages and included questions on: socio-demographics characteristics, sexual behaviours, drug use, history of diagnoses of HIV and STIs, HIV prevention needs, and service uptake.

MeasuresEMIS explored HCV infection through three questions: Have you ever been diagnosed with hepatitis C?, When were you FIRST diagnosed with hepatitis C?, and What is your current hepatitis C status?. Unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) was defined as having had anal intercourse without using a condom at least once in the previous 12 months. “Sex abroad” was defined as having sex while travelling outside Spain. Drugs were grouped for analysis using theoretical and statistical criteria: drugs for sex (popper and erection enhancing medications – e.g. sildenafil citrate), party drugs (ecstasy/metilen-dioxi-metanfetamina – MDMA-, amphetamines, crystal, methamphetamine, mephedrone, LSD, gamma-hydroxylbutyrate/gamma-butyrolactone – GHB/GBL-, ketamine, and cocaine), cannabis/hashish, and “marginal” drugs (heroin and crack). All variables were reported with a temporal reference of the previous 12 months.

ProcedureEMIS was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Portsmouth, UK (REC application number 08/09:21). This study had a collective approach including: government, academic, and NGO sectors; and social media. EMIS was available online for completion over the course of twelve weeks in 2010. Promotion occurred mainly through national and transnational commercial and NGO websites, and social networking websites. A detailed description of the methods is published elsewhere.15,17

AnalysisThe analyses were performed using SPSS©. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to determine median differences for age. Factor analysis was performed to group drugs. Socio-demographic characteristics, sexual practices and risk behaviours among HCV-diagnosed MSM in the last 12 months and undiagnosed were compared using Chi-square test. Z-test was used for the difference between proportions for poly-dichotomous variables. Univariate and multivariate logistic regressions were used to model the relationship between HCV diagnosis in the last 12 months and risk behaviours. Variables with p<0.10 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate model by the backward method and the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) with their respective confidence intervals (95% CI) was calculated. Calibration of the model was proved by Hosmer–Lemeshow test of goodness of fit. The significance level was at 0.05. Final model was adjusted for settlement size, age, educational level, HIV status, and injection-drug use in the last 12 months. MSM diagnosed with HCV more than 12 months ago were excluded of the analysis (n=204).

ResultsPrevalence of HCV and HIV serostatusMSM who had ever been diagnosed with HCV were 1.9% (n=250) of the total sample. Among those, 42% cleared spontaneously without treatment and 26% cleared with treatment. MSM who were currently infected with HCV at the time of the study was 0.6% (n=78). The proportion of MSM who were first diagnosed with HCV in the last 12 months was 0.4% (n=46). From now on the results presented will focus only on the latter group.

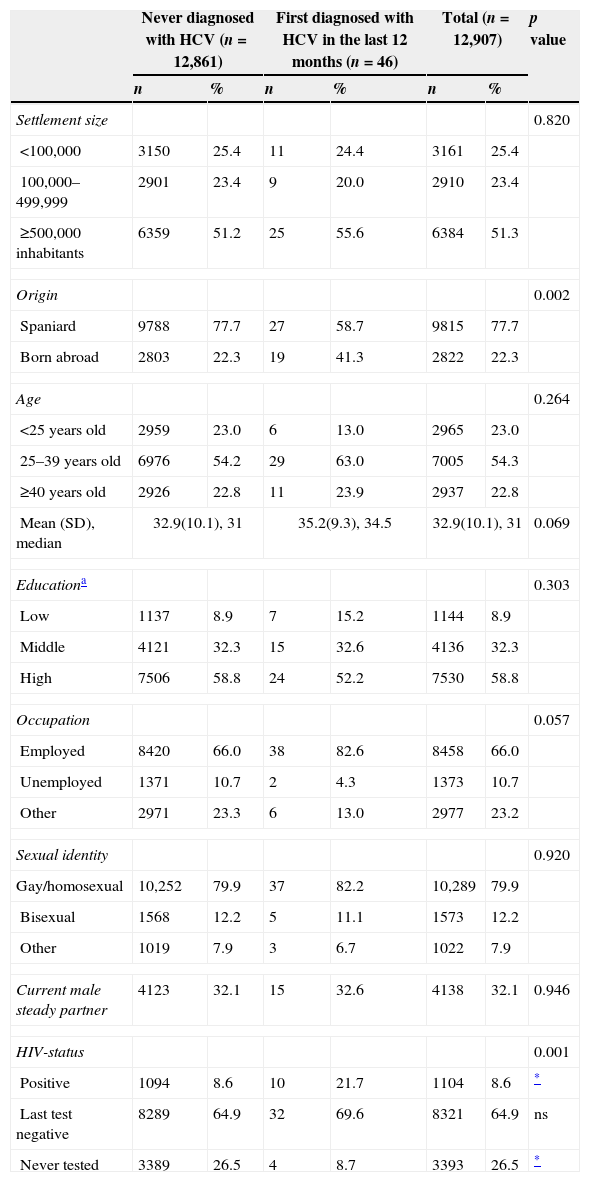

Although most MSM diagnosed with HCV in the previous 12 months were HIV-negative (70%) (Table 1), a higher proportion of HIV-positive MSM were diagnosed with HCV in the previous 12 months (0.9%) than HIV-negative MSM (0.4%). Among HCV-diagnosed MSM and with HIV-negative seroestatus, 81% had been tested for HIV in last 12 months.

Sociodemographic profiles of HCV-diagnosed and never diagnosed respondents.

| Never diagnosed with HCV (n=12,861) | First diagnosed with HCV in the last 12 months (n=46) | Total (n=12,907) | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Settlement size | 0.820 | ||||||

| <100,000 | 3150 | 25.4 | 11 | 24.4 | 3161 | 25.4 | |

| 100,000–499,999 | 2901 | 23.4 | 9 | 20.0 | 2910 | 23.4 | |

| ≥500,000 inhabitants | 6359 | 51.2 | 25 | 55.6 | 6384 | 51.3 | |

| Origin | 0.002 | ||||||

| Spaniard | 9788 | 77.7 | 27 | 58.7 | 9815 | 77.7 | |

| Born abroad | 2803 | 22.3 | 19 | 41.3 | 2822 | 22.3 | |

| Age | 0.264 | ||||||

| <25 years old | 2959 | 23.0 | 6 | 13.0 | 2965 | 23.0 | |

| 25–39 years old | 6976 | 54.2 | 29 | 63.0 | 7005 | 54.3 | |

| ≥40 years old | 2926 | 22.8 | 11 | 23.9 | 2937 | 22.8 | |

| Mean (SD), median | 32.9(10.1), 31 | 35.2(9.3), 34.5 | 32.9(10.1), 31 | 0.069 | |||

| Educationa | 0.303 | ||||||

| Low | 1137 | 8.9 | 7 | 15.2 | 1144 | 8.9 | |

| Middle | 4121 | 32.3 | 15 | 32.6 | 4136 | 32.3 | |

| High | 7506 | 58.8 | 24 | 52.2 | 7530 | 58.8 | |

| Occupation | 0.057 | ||||||

| Employed | 8420 | 66.0 | 38 | 82.6 | 8458 | 66.0 | |

| Unemployed | 1371 | 10.7 | 2 | 4.3 | 1373 | 10.7 | |

| Other | 2971 | 23.3 | 6 | 13.0 | 2977 | 23.2 | |

| Sexual identity | 0.920 | ||||||

| Gay/homosexual | 10,252 | 79.9 | 37 | 82.2 | 10,289 | 79.9 | |

| Bisexual | 1568 | 12.2 | 5 | 11.1 | 1573 | 12.2 | |

| Other | 1019 | 7.9 | 3 | 6.7 | 1022 | 7.9 | |

| Current male steady partner | 4123 | 32.1 | 15 | 32.6 | 4138 | 32.1 | 0.946 |

| HIV-status | 0.001 | ||||||

| Positive | 1094 | 8.6 | 10 | 21.7 | 1104 | 8.6 | * |

| Last test negative | 8289 | 64.9 | 32 | 69.6 | 8321 | 64.9 | ns |

| Never tested | 3389 | 26.5 | 4 | 8.7 | 3393 | 26.5 | * |

No significant differences in the sociodemographic characteristics of MSM diagnosed with HCV in the last 12 months as compared to never diagnosed MSM were found, except for the place or birth (Table 1). While most of those infected were Spaniards (59%), the prevalence of HCV diagnosis in the last 12 months among men born abroad was higher (0.7% vs 0.3% in the Spaniards). The main countries of origin from HCV-diagnosed MSM born abroad were: France, England, Brazil, and other Latin-American countries.

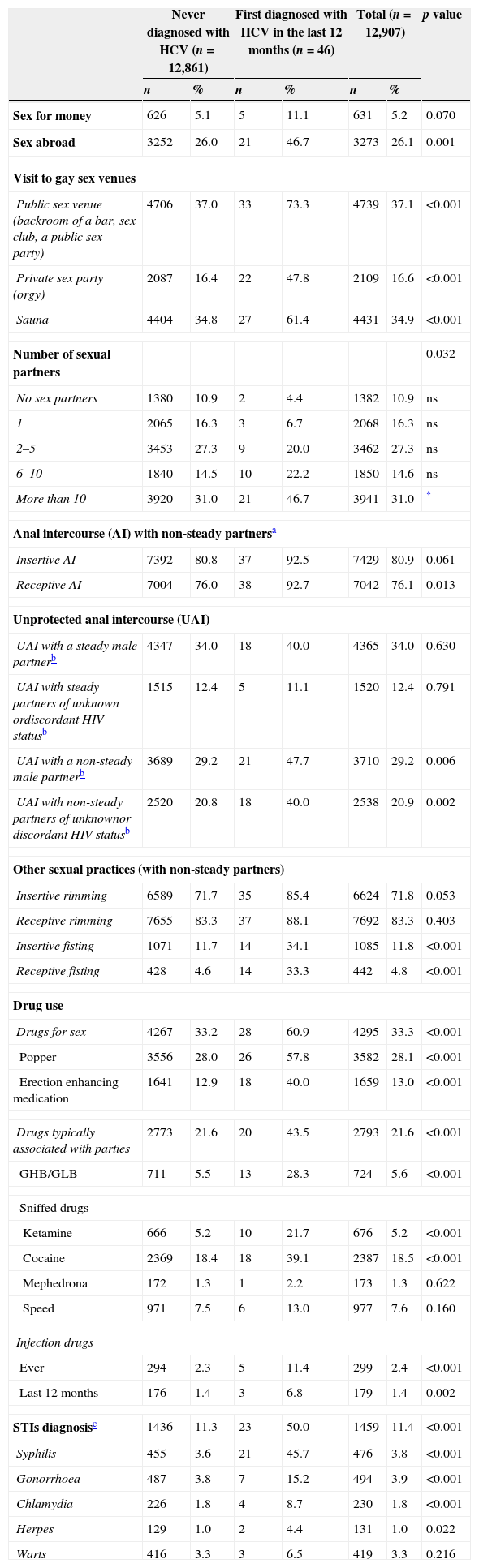

Sex abroad and gay venues most visitedAs shown in Table 2, nearly half of the MSM diagnosed with HCV in the last 12 months had sex abroad in the last 12 months. This is almost double the proportion found among never diagnosed MSM. The most visited countries by HCV diagnosed MSM and where they had sex in last 12 months were England, USA, France, and Germany.

Comparison of sexual behaviour and other variables associated to HCV infection among HCV-diagnosed and never diagnosed respondents.

| Never diagnosed with HCV (n=12,861) | First diagnosed with HCV in the last 12 months (n=46) | Total (n=12,907) | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex for money | 626 | 5.1 | 5 | 11.1 | 631 | 5.2 | 0.070 |

| Sex abroad | 3252 | 26.0 | 21 | 46.7 | 3273 | 26.1 | 0.001 |

| Visit to gay sex venues | |||||||

| Public sex venue (backroom of a bar, sex club, a public sex party) | 4706 | 37.0 | 33 | 73.3 | 4739 | 37.1 | <0.001 |

| Private sex party (orgy) | 2087 | 16.4 | 22 | 47.8 | 2109 | 16.6 | <0.001 |

| Sauna | 4404 | 34.8 | 27 | 61.4 | 4431 | 34.9 | <0.001 |

| Number of sexual partners | 0.032 | ||||||

| No sex partners | 1380 | 10.9 | 2 | 4.4 | 1382 | 10.9 | ns |

| 1 | 2065 | 16.3 | 3 | 6.7 | 2068 | 16.3 | ns |

| 2–5 | 3453 | 27.3 | 9 | 20.0 | 3462 | 27.3 | ns |

| 6–10 | 1840 | 14.5 | 10 | 22.2 | 1850 | 14.6 | ns |

| More than 10 | 3920 | 31.0 | 21 | 46.7 | 3941 | 31.0 | * |

| Anal intercourse (AI) with non-steady partnersa | |||||||

| Insertive AI | 7392 | 80.8 | 37 | 92.5 | 7429 | 80.9 | 0.061 |

| Receptive AI | 7004 | 76.0 | 38 | 92.7 | 7042 | 76.1 | 0.013 |

| Unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) | |||||||

| UAI with a steady male partnerb | 4347 | 34.0 | 18 | 40.0 | 4365 | 34.0 | 0.630 |

| UAI with steady partners of unknown ordiscordant HIV statusb | 1515 | 12.4 | 5 | 11.1 | 1520 | 12.4 | 0.791 |

| UAI with a non-steady male partnerb | 3689 | 29.2 | 21 | 47.7 | 3710 | 29.2 | 0.006 |

| UAI with non-steady partners of unknownor discordant HIV statusb | 2520 | 20.8 | 18 | 40.0 | 2538 | 20.9 | 0.002 |

| Other sexual practices (with non-steady partners) | |||||||

| Insertive rimming | 6589 | 71.7 | 35 | 85.4 | 6624 | 71.8 | 0.053 |

| Receptive rimming | 7655 | 83.3 | 37 | 88.1 | 7692 | 83.3 | 0.403 |

| Insertive fisting | 1071 | 11.7 | 14 | 34.1 | 1085 | 11.8 | <0.001 |

| Receptive fisting | 428 | 4.6 | 14 | 33.3 | 442 | 4.8 | <0.001 |

| Drug use | |||||||

| Drugs for sex | 4267 | 33.2 | 28 | 60.9 | 4295 | 33.3 | <0.001 |

| Popper | 3556 | 28.0 | 26 | 57.8 | 3582 | 28.1 | <0.001 |

| Erection enhancing medication | 1641 | 12.9 | 18 | 40.0 | 1659 | 13.0 | <0.001 |

| Drugs typically associated with parties | 2773 | 21.6 | 20 | 43.5 | 2793 | 21.6 | <0.001 |

| GHB/GLB | 711 | 5.5 | 13 | 28.3 | 724 | 5.6 | <0.001 |

| Sniffed drugs | |||||||

| Ketamine | 666 | 5.2 | 10 | 21.7 | 676 | 5.2 | <0.001 |

| Cocaine | 2369 | 18.4 | 18 | 39.1 | 2387 | 18.5 | <0.001 |

| Mephedrona | 172 | 1.3 | 1 | 2.2 | 173 | 1.3 | 0.622 |

| Speed | 971 | 7.5 | 6 | 13.0 | 977 | 7.6 | 0.160 |

| Injection drugs | |||||||

| Ever | 294 | 2.3 | 5 | 11.4 | 299 | 2.4 | <0.001 |

| Last 12 months | 176 | 1.4 | 3 | 6.8 | 179 | 1.4 | 0.002 |

| STIs diagnosisc | 1436 | 11.3 | 23 | 50.0 | 1459 | 11.4 | <0.001 |

| Syphilis | 455 | 3.6 | 21 | 45.7 | 476 | 3.8 | <0.001 |

| Gonorrhoea | 487 | 3.8 | 7 | 15.2 | 494 | 3.9 | <0.001 |

| Chlamydia | 226 | 1.8 | 4 | 8.7 | 230 | 1.8 | <0.001 |

| Herpes | 129 | 1.0 | 2 | 4.4 | 131 | 1.0 | 0.022 |

| Warts | 416 | 3.3 | 3 | 6.5 | 419 | 3.3 | 0.216 |

By exploring what gay venues were frequented in the last 12 months by HCV diagnosed MSM, we found that, in comparison with never diagnosed MSM, many more visited a sex-focused venues (83% vs 63% in the never diagnosed, p<0.05). The most visited sex venue was a public sex venue (73% vs 37% in the never diagnosed, p<0.001).

Sexual behaviourThe number of sexual partners in the last 12 months (Table 2) was higher among HCV-diagnosed in the last 12 months: more HCV-diagnosed MSM had more than 10 sexual partners than the never diagnosed (47% vs 31%, respectively). By looking at the sexual practices such as insertive and receptive anal intercourse, only receptive anal intercourse with non-steady partners in the last 12 months was more likely among HCV-diagnosed MSM (93% vs 76% in the never diagnosed). If the HIV-status of the non-steady partners of MSM diagnosed with HCV is observed, MSM diagnosed with HCV were more likely to have had UAI with non-steady partners of an unknown or discordant HIV-status. By exploring other sexual practices, HCV diagnosed MSM were more likely to practice both insertive (34% vs 12% in the never diagnosed) and receptive (33% vs 5% in the never diagnosed) fisting.

Drug use and STI diagnosisAs seen in Table 2, HCV-diagnosed MSM had the higher percentages of consumption of drugs, both drugs for sex (61% vs 33% in the never diagnosed) and party drugs (44% vs 22% in the never diagnosed). Individually, use of popper, erection enhancing medications, GHB/GLB, cocaine and ketamine was higher among HCV diagnosed MSM. With respect to injecting drugs, a higher proportion of HCV-diagnosed MSM had injected any drug in the last 12 months (6.8% vs 1.4% in the never diagnosed).

Regarding STI, MSM diagnosed with HCV had almost five times the diagnosis of a bacterial or ulcerative STI in the last 12 months (50% vs 11% in the never diagnosed). Most common STI among HCV diagnosed MSM was syphilis (46% vs 4% in the never diagnosed).

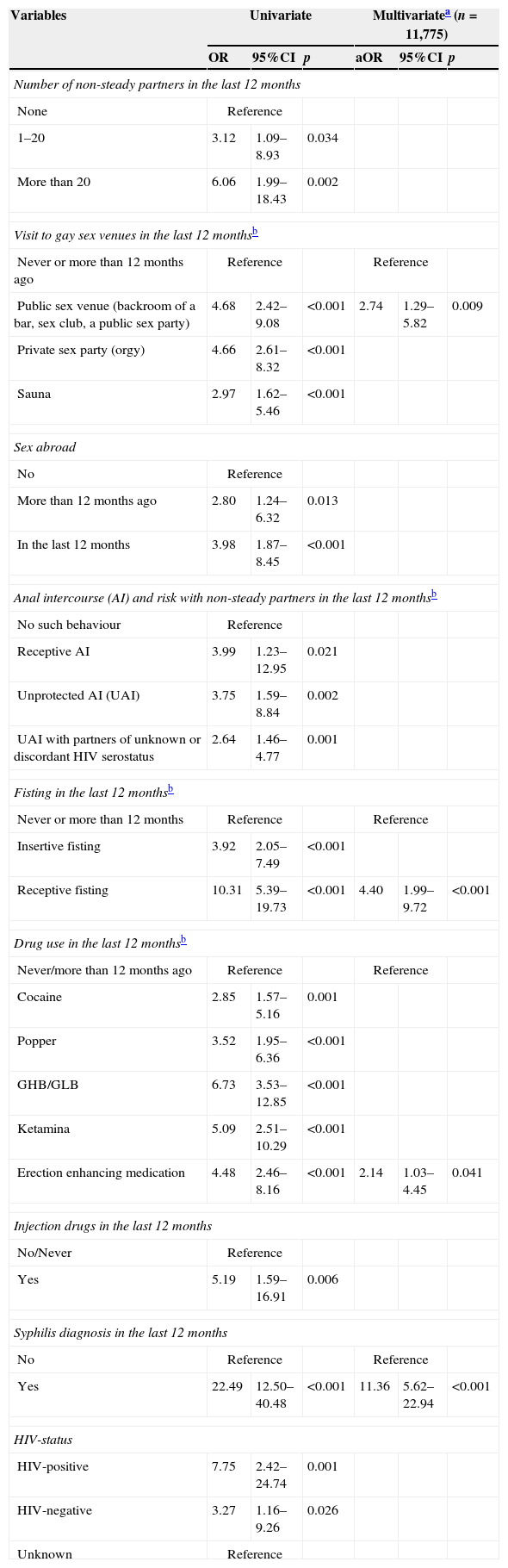

Factors associated with a first diagnosis of HCV in the last 12 monthsIn multivariate model (Table 3), a first diagnosis of HCV in the last 12 months was associated with having attended a public sex venue (aOR 2.74, p=0.009), having practiced receptive fisting (aOR 4.40, p<0.001), having used erection enhancing medication (aOR 2.14, p=0.041), and having been diagnosed with syphilis (aOR 11.36, p<0.001).

Factors associated to a first diagnosis of HCV in the last 12 months.

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariatea (n=11,775) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | p | aOR | 95%CI | p | |

| Number of non-steady partners in the last 12 months | ||||||

| None | Reference | |||||

| 1–20 | 3.12 | 1.09–8.93 | 0.034 | |||

| More than 20 | 6.06 | 1.99–18.43 | 0.002 | |||

| Visit to gay sex venues in the last 12 monthsb | ||||||

| Never or more than 12 months ago | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Public sex venue (backroom of a bar, sex club, a public sex party) | 4.68 | 2.42–9.08 | <0.001 | 2.74 | 1.29–5.82 | 0.009 |

| Private sex party (orgy) | 4.66 | 2.61–8.32 | <0.001 | |||

| Sauna | 2.97 | 1.62–5.46 | <0.001 | |||

| Sex abroad | ||||||

| No | Reference | |||||

| More than 12 months ago | 2.80 | 1.24–6.32 | 0.013 | |||

| In the last 12 months | 3.98 | 1.87–8.45 | <0.001 | |||

| Anal intercourse (AI) and risk with non-steady partners in the last 12 monthsb | ||||||

| No such behaviour | Reference | |||||

| Receptive AI | 3.99 | 1.23–12.95 | 0.021 | |||

| Unprotected AI (UAI) | 3.75 | 1.59–8.84 | 0.002 | |||

| UAI with partners of unknown or discordant HIV serostatus | 2.64 | 1.46–4.77 | 0.001 | |||

| Fisting in the last 12 monthsb | ||||||

| Never or more than 12 months | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Insertive fisting | 3.92 | 2.05–7.49 | <0.001 | |||

| Receptive fisting | 10.31 | 5.39–19.73 | <0.001 | 4.40 | 1.99–9.72 | <0.001 |

| Drug use in the last 12 monthsb | ||||||

| Never/more than 12 months ago | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Cocaine | 2.85 | 1.57–5.16 | 0.001 | |||

| Popper | 3.52 | 1.95–6.36 | <0.001 | |||

| GHB/GLB | 6.73 | 3.53–12.85 | <0.001 | |||

| Ketamina | 5.09 | 2.51–10.29 | <0.001 | |||

| Erection enhancing medication | 4.48 | 2.46–8.16 | <0.001 | 2.14 | 1.03–4.45 | 0.041 |

| Injection drugs in the last 12 months | ||||||

| No/Never | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 5.19 | 1.59–16.91 | 0.006 | |||

| Syphilis diagnosis in the last 12 months | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Yes | 22.49 | 12.50–40.48 | <0.001 | 11.36 | 5.62–22.94 | <0.001 |

| HIV-status | ||||||

| HIV-positive | 7.75 | 2.42–24.74 | 0.001 | |||

| HIV-negative | 3.27 | 1.16–9.26 | 0.026 | |||

| Unknown | Reference | |||||

In this study, the sample size of the HCV-diagnosed MSM in the last 12 months is small. Therefore results should be interpreted with caution. In spite of this, the findings provide clues about the patterns in sexual behaviours that could add some understanding on the transmission of HCV in MSM.

Overall HCV prevalence in this study (0.6%) was lower compared with data from the general population in Spain (2.5%)18 and HCV prevalence among MSM from other countries,19,20 which may indicate that HCV infection appeared later among MSM in Spain.13,14 This is consistent with the fact that the first outbreak of HCV in Spain among MSM was reported in 2010,12 ten years after the first outbreak in Europe in the same population.2 However, we must take into account that the prevalence of HCV was self-reported and that a possible underdiagnosis can occur due to the absence, in many cases, of symptoms of HCV. In this study, a diagnosis of HCV does not allude to acute HCV infection.

There is not a consistent socio-demographic profile of MSM with a diagnosis of HCV in the last 12 months in comparison with never diagnosed, except for the origin of the HCV-diagnosed men. The prevalence was significantly higher in those who were born abroad, which reaffirms a high vulnerability for acquiring STIs, including HIV and HCV16 among migrant population. Among MSM born abroad, factors associated to their higher vulnerability to HCV acquisition could be the same as with HIV. Most likely, many MSM born abroad are infected in Spain whereas most non-MSM migrants are likely to have been infected with HCV in their country of origin.18

In this sample, MSM diagnosed with HCV in the last 12 months are mostly HIV-negative. However, this result is not in concordance with most reports of HCV among MSM, which indicate that those most affected by HCV are HIV-positive.4,6,21 Until now it was unclear to what extent HIV-negative MSM are also at risk of HCV infection. Our results indicate that HIV infection is not an absolute prerequisite for sexually acquired HCV. We do not know if HIV-negative men knew of their diagnosis of HCV as a result of abnormal liver transaminases, hepatitis symptoms or through HCV testing after a diagnosis of STI. A possible explanation of how HIV-negative MSM were diagnosed with HCV is having had a STI diagnosis in the last 12 months. Half of them were diagnosed with any STI and perhaps healthcare providers recommended tests for other STIs. Public health agents should be alert because apparently the infection is expanding among all MSM in Spain. However, we should not lose sight that the prevalence of HCV is higher among HIV-positive men which may be due to routine medical screening. In Spain, liver function markers are controlled each time that HIV-positive people have their medical visit to monitor the infection (at least, 2–4 times per year).

Although the prevalence of the use of injected-drugs in the last 12 months among HCV-diagnosed MSM was higher (6.8%) than the rest of MSM (1.4%), this does not provide an explanation to understand the occurrence of HCV infection among MSM. Instead, most HCV-diagnosed MSM in the last 12 months were men who were exposed in high sexual risk practices (as such receptive anal sex, group sex, fisting, non-concordant UAI with non-steady partners). Some sexual practices, like fisting, can lead to rectal bleeding which has been described as the main route in the sexual transmission of the HCV,22,23 and this is confirmed by the multivariate analysis which reveals that receptive fisting is associated with a diagnosis of HCV. Furthermore, in order to understand the dynamics of sexual transmission of HCV among MSM, it is important to place it in the situational context in which these practices happen. For instance, if someone participates in a sex party, more likely this person could have sex with many men, have fisting or/and UAI (in some cases with HIV-positive men), and use drugs. All this context will elevate the risk of HCV infection. The importance of sex parties and the situational context in the transmission of HCV is highlighted by the results of the multivariate analysis which show that to attend public sex-focused venues is associated with a diagnosis of HCV. This is important to acknowledge because by knowing the public meeting places of these men, targeted interventions can be designed.

Drug use seems to be associated with HCV infection. Its role in UAI and HCV acquisition has also been found in other countries.24,25 This study found a possible link between types of substance use for certain sexual practices which can be facilitators of HCV infection. Popper, cocaine and ketamine were highly used by HCV-diagnosed MSM which are related to the practice of fisting. Popper is used to facilitate penetration by relaxing the anal sfinter. Popper use raises the likelihood of HCV infection due to vasodilation in the rectal mucosa, which increases the probability of rectal bleeding. Cocaine and ketamine act as muscle relaxants, anaesthetics, and aphrodisiacs. Because of its anaesthetic effects, ketamine and cocaine can stop people from feeling pain. Due to this, its use has been widely reported for anal sex, particularly fisting. While these drugs are usually sniffed, they can also be used internally in the anus. This allows them to be absorbed faster, take effect more quickly, as well as serving as an anaesthetic. As it contains acid substances, the risk is that it can produce mucosal damage.26 In multivariate analysis, use of erection enhancing medication was associated with HCV diagnosis. Some drugs used as sexual stimulant (e.g. cocaine), might have erectile dysfunction as a side effect, for which erection enhancing medication is used. However, this association requires further investigation.

Other factor that can be associated with HCV acquisition is the sex while abroad. Almost half of HCV diagnosed MSM had travelled and had sex abroad. There is evidence of the role of international mobility and sexual behaviour regarding the spread of STIs among MSM in Europe, while travelling abroad.27,28 Molecular phylogenetic studies of HCV suggested evidence of a large international transmission network of MSM in Europe, mostly in the larger cities (Paris, Amsterdam, London).2 Men who are part of certain sexual subcultures (e.g. leather, sado-masochism) or who attend gay festive events (circuit parties) can travel to European cities where large events or parties related to their sexual interests are organised. This allows the building of international social and sexual networks of men who share the same sexual interests. The existence of these networks, in which Spanish MSM have travelled to other countries with higher HCV prevalence or European MSM travelled to Spain (Spain is the most favourite destination for MSM in Europe15), may have facilitated the transmission of HCV infection among MSM in Spain. HCV diagnosed MSM who had sex abroad in the last 12 months could have been easily infected abroad. However, this needs to be confirmed with further studies.

A temporal occurrence between STIs and HCV has been observed in this study. Some STIs, such as syphilis, may facilitate HCV infection. Sexual transmission of HCV is probably mediated by ulcerative STIs that may cause mucosal damage in the rectum.1,5,9,29 Outbreaks of acute hepatitis C since the year 2000 in larger Western European urban areas is coincident with a dramatic increase in the incidence of syphilis among MSM.14 The shared route of transmission of the two infections is the most likely explanation for this association.5 The strong relationship between syphilis and HCV is confirmed in the multivariate model. Recommendation of screening for STIs should be taken into account for sexually active MSM. Particularly, a positive syphilis test result should be an important warning sign and lead to counselling on how to prevent HCV and selective HCV testing according to individual high-risk profile.

More studies in Spain are needed on HCV in MSM which include exploring other sexual practices or situations that can be associated to HCV risk (e.g. shared use of sex toys, double anal penetration, anal or penile bleeding during sex, enema use before sex). It would also be important to identify the needs of HCV-diagnosed people and the psychological impact of being diagnosed with HCV and living with HCV.

Primary care and consultation for medical checks of HIV-positive MSM can be important venues to identify men with high-risk behaviours and primary prevention should be done with them. Prevention messages should include information about HCV infection: transmission, symptomatology, sexual risk reduction strategies (e.g. use gloves for fisting, no anal douches before sex, no share lube for fisting, have available disinfectant wipes in sex parties), treatment and re-infection. Interventions that target specific commercial sex-focused venues should be strengthened and greater efforts are needed to develop strategies to reach men who participate in private group sexual encounters.

As it has already been mentioned, a limitation of this study is the sample size that impedes making greater generalisations (e.g. an effect of this are the wide 95% confidence intervals in the multivariate model). Other big limitation is that diagnosis of HCV was self-reported. Self-referred diagnosis during the last 12 months does not imply acute HCV infection. Thus, current sexual and risk behaviours may not be related with HCV infection. Also, there can be an informative bias, as some MSM may not be aware of all the clinical tests performed to them or as not all MSM included in the survey underwent HCV testing. We cannot give a quantification of this bias by providing the number of MSM without HCV serology since that questions on HCV were asked for diagnosis and not for testing. This precludes having a picture more exact about HCV infection among MSM. EMIS study used self-report measures of sexual practices and risk behaviours. Because of the socially sensitive nature of these behaviours, participants could have underreported their risk behaviours. Other limitation is that the sample has been captured primarily on the Internet. The profile of respondents surveyed via Internet can differ in many aspects from a sample survey in gay venues30 and it is probably not representative of the MSM population living in Spain.

ConclusionHIV infection does not seem an absolute prerequisite for sexually acquired HCV among MSM in Spain. The profile of HCV-diagnosed MSM in the last 12 months was men who were exposed to high sexual risk practices (e.g. receptive fisting) which are associated with HCV infection. Diagnosis of syphilis is strongly associated to a diagnosis of HCV.

ContributorsThe initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by PFD, critiqued by CF, LF, RS, MD and JC, and repeatedly circulated among all authors for data interpretation and for critical revision.

FundingThe EMIS project was funded by Executive Agency for Health and Consumers (EAHC) (Grant Agreement 2008 12 14), EU Health Programme 2008–2013, co-funded by the five Associated Partners (Centre de Estudis Epidemiològics sobre les ITS i SIDA de Catalunya (CEEISCAT); Department of Health for England; Regione del Veneto; Robert Koch Institute, and Maastricht University). In Spain EMIS was supported by the Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

We thank more than 13,100 men who responded to the survey in Spain, the website Bakala who placed our banner for free. We also thank all the NGOs and AIDS Autonomous Plans for collaborating in the diffusion of the survey. Without this help, EMIS's success would not have been possible. We would like to acknowledge the scientists: Axel J. Schmidt (Project co-ordination); Ulrich Marcus (Project initiation and supervision); Peter Weatherburn (Promotion co-ordination); Ford Hickson and David Reid (Technical implementation) and the European MSM Internet Survey network.