The aim was to examine the health status and infectious diseases in a cohort of unaccompanied immigrant minors (UIMs) from Africa in Spain, and to detect if there are differences according to the geographical area of origin.

MethodsCross-sectional study in 622 African male UIMs at the time of admission to residential care in Aragon (Spain) during 2005-2019. A physical, nutritional and laboratory examination was performed following sanitary guidelines.

ResultsThe mean age of the African UIMs was 16.1 years (SD 1.7; range 13-17). 88.9% were from Maghreb (mean age 15.9 years; SD 1.5) and 14.1% from Western Sub-Saharan (mean age 16.8 years; SD 1). We found that the prevalence of caries, iron deficiency and dermatological problems was significantly higher (p<.05) among Maghrebian, and the prevalence of past and present hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, intestinal parasitosis, eosinophilia (p<.00001) and latent tuberculosis (p=.0034) was significantly higher in those of Sub-Saharan origin.

ConclusionThe most relevant finding was the high prevalence of present HBV infection (14.8%) among Sub-Saharan adolescents. This finding highlights the importance of recommending targeted screening, preventive vaccination programs, and integration into local health care systems that allow for long-term treatment and follow-up as a way to prevent the transmission of HBV infection.

El objetivo fue estudiar el estado de salud y las enfermedades infecciosas de una cohorte de menores inmigrantes no acompañados (MENA) procedentes de África en España, y detectar si existen diferencias según la zona geográfica de origen.

MétodosEstudio transversal en 622 MENA varones africanos en el momento de su admisión en la atención residencial en Aragón (España) entre 2005 y 2019. Se realizó un examen físico, nutricional y analítico de laboratorio siguiendo las directrices sanitarias.

ResultadosLa edad media de los MENA africanos era de 16,1 años (DE 1,7, intervalo 13-17). El 88,9 % procedía del Magreb (edad media 15,9 años; DE 1,5) y el 14,1 % de la zona subsahariana occidental (edad media 16,8 años; DE 1). Se constató que la prevalencia de caries, ferropenia y problemas dermatológicos era significativamente mayor (p < 0,05) entre los magrebíes, y que la prevalencia de infección pasada y presente por el virus de la hepatitis B (VHB), parasitosis intestinal, eosinofilia (p < 0,00001) y tuberculosis latente (p = 0,0034) era significativamente mayor entre los sujetos de origen subsahariano.

ConclusiónEl dato más relevante fue la alta prevalencia de infección actual por el VHB (14,8 %) entre los adolescentes subsaharianos. Este hallazgo pone de relieve la importancia de recomendar cribados selectivos, programas de vacunación preventiva e integración en los sistemas locales de atención sanitaria que permitan un tratamiento y seguimiento a largo plazo como manera de prevenir la transmisión de la infección por el VHB.

In Spain the reception of unaccompanied immigrant minors (UIMs)* has been taking place for more two decades. This phenomenon was small between the years 1996-2000, but since 2001 there has been a remarkable and sustained growth. Specifically, during the 2015-2017 period of the 104,044 minors in foster care in Spain, 10,251 (9.85%) were UIMs. Ninety-eight percent of the UIMs that arrive in Spain are male adolescents aged 13-17 years from the countries of the Maghreb and West Sub-Saharan Africa.1

These adolescents may present with untreated or chronic health problems, imported infectious diseases, and psychophysical pathologies derived from the causes and process of migration. The health of the UIMs is one of the main aspects to be considered when they are in foster care, as their physical and psychological well-being may determine their personal development in the future.2

The objective of this study was to examine the health status and infectious diseases in a cohort of UIMs from the African continent at the time of their residential placement in Spain, and detect if there are differences according to geographical area of origin.

* Note: MENA (Menores Extranjeros No Acompañados) it is the acronym that is used in Spain to technically name these migrant children under the age of 18, who are separated from their parents and who are also not under the care of any other adult.

MethodsAn observational and descriptive study of cross-sectional and retrospective design was conducted on a cohort of 622 male UIMs from Africa in the Autonomous Community of Aragon (Spain) during the period 2005-2019.

Two female, both of sub-Saharan origin, were also evaluated during the study period. They represented 0.3% of the total UIMs sample and 2% of sub-Saharan UIMs. They were excluded from the study because they represented a low percentage and to avoid gender bias when comparing both populations of male minors.

Following sanitary guidelines for the evaluation of UIMs residents in protection centers, a complete physical examination, nutritional anthropometry, blood count, iron metabolism, basic biochemical profile, tuberculin skin test (2 TU PPD RT-23), serology for hepatitis B virus (HBV) (HBsAg, anti-HBc, anti-HBs), hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV) and human immunodeficiency virus (anti-HIV) and reaginic serology of syphilis (RPR) were systematically performed at the time of admission to residential care. In the presence of eosinophilia (more than 500 cells/microL) stool parasite investigation was conducted. Patients with a tuberculin skin test greater than 10mm were considered infected by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, regardless of the existence or not of the BCG vaccine history. The existence of HBsAg was considered present HBV infection, and past HBV infection the existence of anti-HBc and anti-HBs with negative HBsAg. The Body Mass Index was calculated to define the nutritional status.3,4

Management of detected health problems. All the children were evaluated in the specialized unit in UIMs of the pediatrics and adolescence service of the Social Services Institute of Aragón. The UIMs with dental, infectious, ophthalmologic, ENT, orthopedic and cardiovascular pathologies were referred to specialized units for their treatment and control.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants before participation. The study complied with the principles of Helsinki and was ethically approved by the review committee of the Social Services Institute of Aragon.

Data analysis. An Excel® sheet was used to calculate the arithmetic mean and standard deviation (SD) of the age of the minors and the percentage of health problems in the total number of UIMs according to their geographical origin. Statistical analyses were carried out with Social Science Statistics® program. For the comparison of population proportions the two-tailed Z test was used with a significance level of p <0.05.

ResultsThe mean age of the 622 African male UIMs was 16.1 years (SD 1.7; range 13-17). 88.9% (n=534) were of Maghreb origin (Morocco, 476; Algeria, 58), with a mean age of 15.9 years (SD 1.5; range 13-17). The remaining 14.1% (n=88) were of Western Sub-Saharan origin (Ghana, 26; Mali, 17; Guinea Conakry, 17; Senegal, 10; Gambia, 8; Sierra Leone, 3; Liberia, 2; Guinea Bissau, 2; Ivory Coast, 1; Nigeria 1; Burkina Faso, 1), with a mean age of 16.8 years (SD 1; range 14-17).

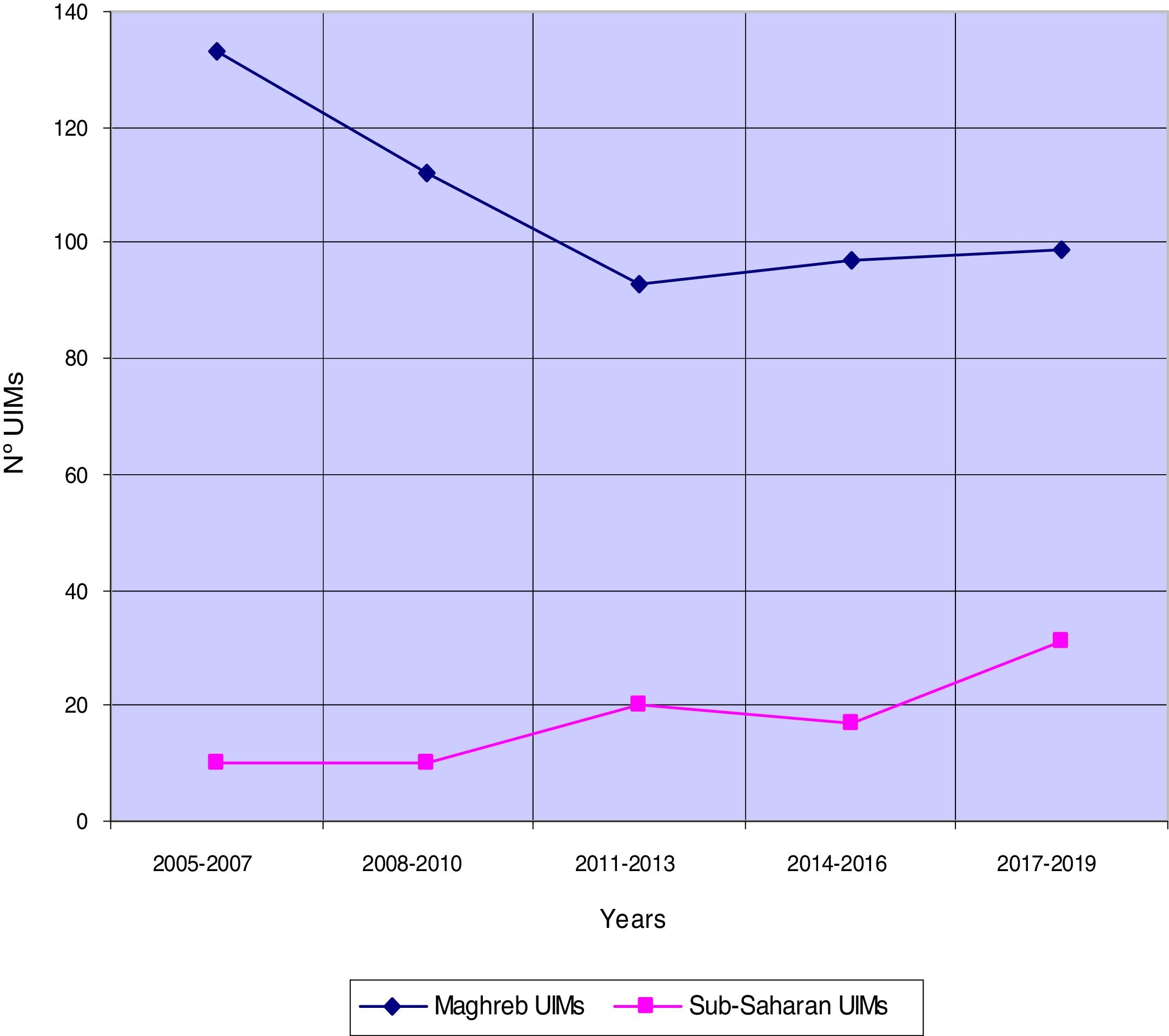

Figure 1 shows the temporal trends in the arrival of African UIMs to Spain. In the Maghreb UIMs, a decrease between the years 2011-2013 and a slight increase maintained in the last six years was observed. Sub-Saharan UIMs showed an increase in the last three years.

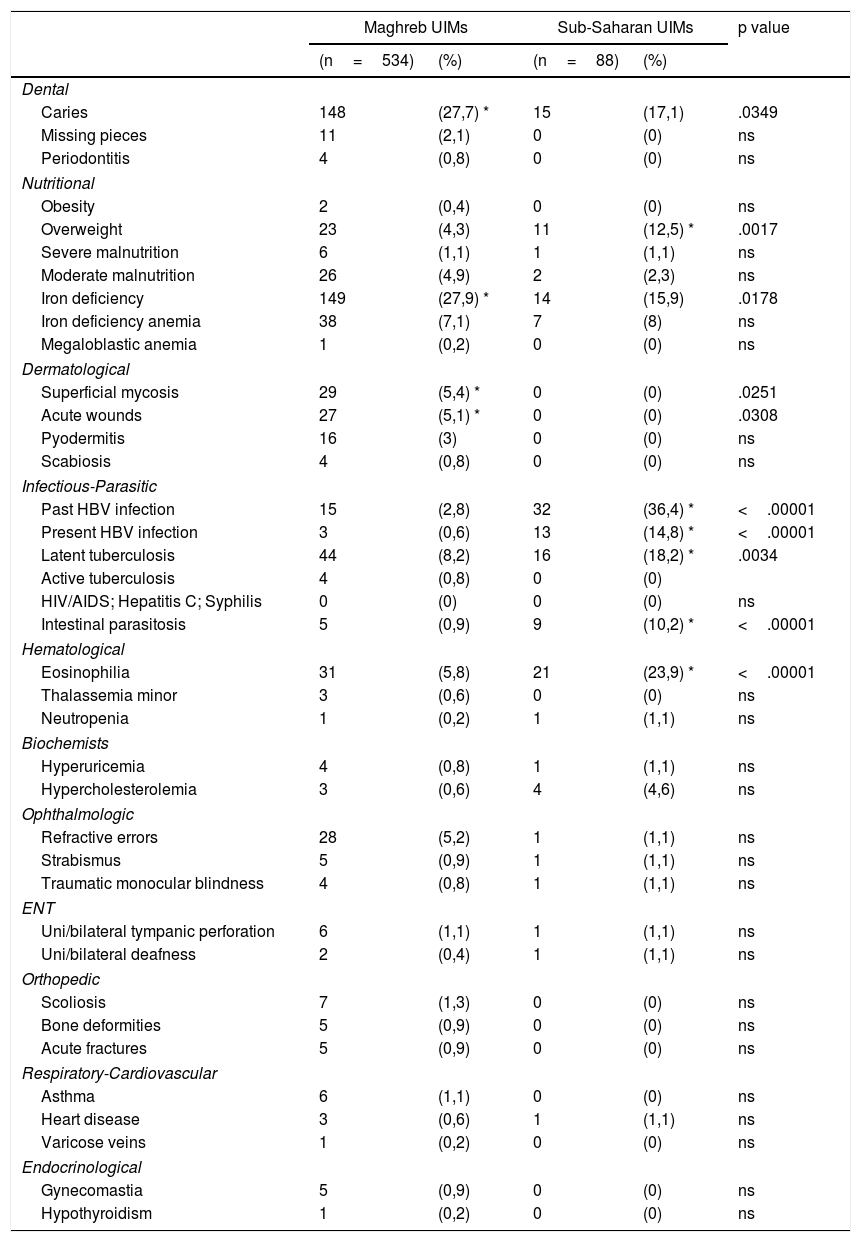

In Table 1 the health problems and infectious diseases detected in the UIMs of Maghreb and Sub-Saharan origin are detailed and compared. In those of Maghreb origin, the prevalence of caries, iron deficiency and dermatological problems was significantly higher. In those of Sub-Saharan origin, the prevalence of past and present HBV infection, latent tuberculosis, intestinal parasitosis, eosinophilia and overweight was significantly higher.

Health problems and infectious diseases in unaccompanied immigrant minors (UIMs) from Africa in Spain.

| Maghreb UIMs | Sub-Saharan UIMs | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=534) | (%) | (n=88) | (%) | ||

| Dental | |||||

| Caries | 148 | (27,7) * | 15 | (17,1) | .0349 |

| Missing pieces | 11 | (2,1) | 0 | (0) | ns |

| Periodontitis | 4 | (0,8) | 0 | (0) | ns |

| Nutritional | |||||

| Obesity | 2 | (0,4) | 0 | (0) | ns |

| Overweight | 23 | (4,3) | 11 | (12,5) * | .0017 |

| Severe malnutrition | 6 | (1,1) | 1 | (1,1) | ns |

| Moderate malnutrition | 26 | (4,9) | 2 | (2,3) | ns |

| Iron deficiency | 149 | (27,9) * | 14 | (15,9) | .0178 |

| Iron deficiency anemia | 38 | (7,1) | 7 | (8) | ns |

| Megaloblastic anemia | 1 | (0,2) | 0 | (0) | ns |

| Dermatological | |||||

| Superficial mycosis | 29 | (5,4) * | 0 | (0) | .0251 |

| Acute wounds | 27 | (5,1) * | 0 | (0) | .0308 |

| Pyodermitis | 16 | (3) | 0 | (0) | ns |

| Scabiosis | 4 | (0,8) | 0 | (0) | ns |

| Infectious-Parasitic | |||||

| Past HBV infection | 15 | (2,8) | 32 | (36,4) * | <.00001 |

| Present HBV infection | 3 | (0,6) | 13 | (14,8) * | <.00001 |

| Latent tuberculosis | 44 | (8,2) | 16 | (18,2) * | .0034 |

| Active tuberculosis | 4 | (0,8) | 0 | (0) | |

| HIV/AIDS; Hepatitis C; Syphilis | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | ns |

| Intestinal parasitosis | 5 | (0,9) | 9 | (10,2) * | <.00001 |

| Hematological | |||||

| Eosinophilia | 31 | (5,8) | 21 | (23,9) * | <.00001 |

| Thalassemia minor | 3 | (0,6) | 0 | (0) | ns |

| Neutropenia | 1 | (0,2) | 1 | (1,1) | ns |

| Biochemists | |||||

| Hyperuricemia | 4 | (0,8) | 1 | (1,1) | ns |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 3 | (0,6) | 4 | (4,6) | ns |

| Ophthalmologic | |||||

| Refractive errors | 28 | (5,2) | 1 | (1,1) | ns |

| Strabismus | 5 | (0,9) | 1 | (1,1) | ns |

| Traumatic monocular blindness | 4 | (0,8) | 1 | (1,1) | ns |

| ENT | |||||

| Uni/bilateral tympanic perforation | 6 | (1,1) | 1 | (1,1) | ns |

| Uni/bilateral deafness | 2 | (0,4) | 1 | (1,1) | ns |

| Orthopedic | |||||

| Scoliosis | 7 | (1,3) | 0 | (0) | ns |

| Bone deformities | 5 | (0,9) | 0 | (0) | ns |

| Acute fractures | 5 | (0,9) | 0 | (0) | ns |

| Respiratory-Cardiovascular | |||||

| Asthma | 6 | (1,1) | 0 | (0) | ns |

| Heart disease | 3 | (0,6) | 1 | (1,1) | ns |

| Varicose veins | 1 | (0,2) | 0 | (0) | ns |

| Endocrinological | |||||

| Gynecomastia | 5 | (0,9) | 0 | (0) | ns |

| Hypothyroidism | 1 | (0,2) | 0 | (0) | ns |

ns: not significant; * p<.05.

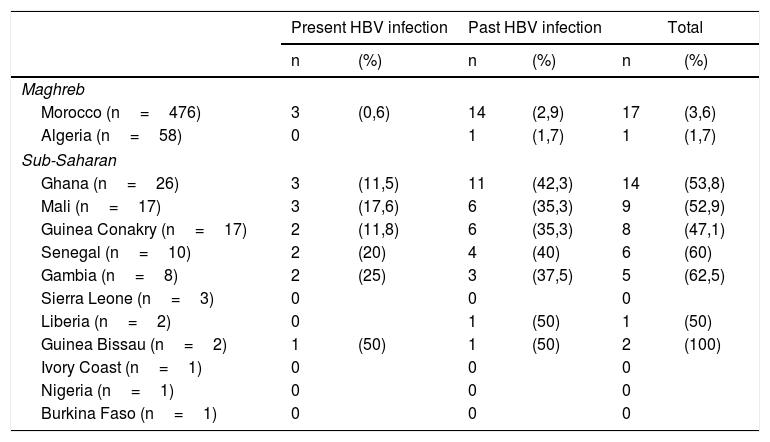

Table 2 shows the prevalence of present and past HBV infection by country of origin. The UIMs of Ghana, Mali, Senegal, Gambia and Guinea Bissau presented a prevalence of present and past HBV infection greater than 50%.

Prevalence of present and past HBV infection by country of origin in unaccompanied immigrant minors (UIMs) from Africa in Spain.

| Present HBV infection | Past HBV infection | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Maghreb | ||||||

| Morocco (n=476) | 3 | (0,6) | 14 | (2,9) | 17 | (3,6) |

| Algeria (n=58) | 0 | 1 | (1,7) | 1 | (1,7) | |

| Sub-Saharan | ||||||

| Ghana (n=26) | 3 | (11,5) | 11 | (42,3) | 14 | (53,8) |

| Mali (n=17) | 3 | (17,6) | 6 | (35,3) | 9 | (52,9) |

| Guinea Conakry (n=17) | 2 | (11,8) | 6 | (35,3) | 8 | (47,1) |

| Senegal (n=10) | 2 | (20) | 4 | (40) | 6 | (60) |

| Gambia (n=8) | 2 | (25) | 3 | (37,5) | 5 | (62,5) |

| Sierra Leone (n=3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Liberia (n=2) | 0 | 1 | (50) | 1 | (50) | |

| Guinea Bissau (n=2) | 1 | (50) | 1 | (50) | 2 | (100) |

| Ivory Coast (n=1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Nigeria (n=1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Burkina Faso (n=1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

The objective of this study was to examine the health status and infectious diseases of UIMs from the African continent in Spain and detect if there are differences according to geographical area of origin.

In those of Maghreb origin, the prevalence of caries, iron deficiency and dermatological problems was significantly higher. We believe that the main causal factors were poor or inadequate native dietary and hygiene habits.5–7

In those of Sub-Saharan origin, the prevalence of past and present HBV infection, latent tuberculosis, intestinal parasitosis and eosinophilia was significantly higher. These findings are similar to those observed in other national studies carried out with immigrant children from Sub-Sahara Africa with their family, and it is well documented that the most frequent cause of absolute eosinophilia is intestinal parasitosis.8,9 Regarding the high prevalence of overweight in these children, we must indicate that it was at the expense of greater muscle mass and not fat mass.

The most relevant finding of this study was the high prevalence (14.8%) of present HBV infection in UIMs from West Sub-Saharan Africa.

HBV is the most common cause of hepatitis worldwide. It is estimated that 2 billion people have evidence of past or present infection with HBV, 240 million are chronic carriers of HBsAg, and around 650,000 people die each year from the complications of chronic HBV. The spread of chronic HBV infection differs widely from one geographical area to another, and the prevalences of HBsAg chronic carriers classify the level of endemicity as low (< 2%), low intermediate (2-4%), high intermediate (5-7%) and high (> 8%) in different countries. HBV endemicity is high in Sub-Saharan Africa.10 Systematic review researches estimate that the prevalence of present HBV infection among the migrant Sub-Saharan population in Spain ranges from 8.4% to 15%.11–13

The management of HBV infection in UIMs is difficult and requires expert personnel and dedicated structures for their assistance. The social services, voluntary operators and cultural mediators are essential to achieve optimized psychological and clinical intervention.13 Given the great health and economic impact that the progressive increase of UIMs in Spain with this chronic and transmissible disease can have, it is essential to have studies that bring us closer to the knowledge of the real situation of HBV infection in this population group, and to be able to plan specific strategies for detection, treatment and prevention of transmission.

In the context of UIMs, World Health Organization guidelines recommend targeted screening, preventative vaccination programs, integration into the local health-care systems allowing for long-term treatment and follow-up, and the diffusion of national educational campaigns as a form of HBV infection transmission prevention.2,10

We consider that the present study has some limitations. First, the African UIMs included in our study were evaluated after arrival in Aragon, an inland region located in the northeast of Spain, so it is possible that they are not a completely representative sample of all the African UIMs that arrive in Spain. Secondly, the stool parasite investigation was performed only in the UIMs that presented gastrointestinal symptoms or eosinophilia, so it is highly probable that the prevalence of intestinal parasitosis that we have observed in this study is lower than that which would have been observed by conducting such investigation systematically.

In conclusion, given the progressive increase of sub-Saharan UIMs in Spain with this chronic and transmissible disease, it is essential to have studies that bring us closer to the knowledge of the real situation of HBV infection in this population group, and to be able to plan specific strategies for detection, treatment and prevention of transmission. These recommendations provide opportunities to save lives, improve clinical outcomes of persons living with chronic hepatitis B, reduce HBV incidence and transmission, and stigma due to disease, but they also pose practical challenges to policy-makers and implementers in our country.

Previous presentationNo

Ethical ApprovalThe study complied with the principles of the 1964 Helsinki declaration. The study was reviewed and approved by the ethics review committee of the Social Services Institute of Aragon.

Informed consentInformed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

FundingThe study received no external funding.

Conflict of interestThe author declares that he has no conflict of interest.