International travelers have grown significantly over last years, as well as imported diseases from tropical areas. Information in pediatric population is scarce. We describe demographic and clinical characteristics of febrile children coming from the tropics.

MethodsRetrospective review of patients under 18 years old, presenting at a tertiary hospital and surrounding primary health care centers between July 2002 and July 2018 with a stay in a tropical region during the previous year. Patients were selected from microbiological charts of thick smears for malaria or dengue serologies.

Results188 patients were studied: 52.7% were born in Spain with a median age of 3.0 years old (IQR 1.5–8.0). Main regions of stay were Sub-Saharan Africa (54.8%) and Latin America (29.8%), mostly for visiting their friends and relatives (56.3%), followed by recent arrival migrants (32.4%). Only 34% of travelers attended pre-travel consultation. More than 80% of these febrile children attended directly the Emergency Room. The most frequent diagnoses were febrile syndrome without source (56.4%), respiratory condition (15.4%) and acute diarrhea (11.7%). Around a half (52.1%) were managed as outpatients, but 46.2% were hospitalized and 7.4% were admitted to Intensive Care Unit. No specific diagnosis was achieved in 24% of cases. However, 29.7% were diagnosed with malaria.

ConclusionChildren with fever coming from tropical areas were at risk of severe infectious diseases. Malaria was diagnosed in one out of four and 7% required admission in PICU. This information emphasizes the need of reinforcing training about tropical diseases among first line physicians.

Los viajes internacionales han aumentado en los últimos años, así como las enfermedades importadas. Los datos en edad pediátrica son escasos. El objetivo de este estudio es describir las características clínico-epidemiológicas del niño con fiebre que viene del trópico.

MétodosRevisión retrospectiva de pacientes menores de 18 años que, tras una estancia en zona tropical en el último año, acuden con fiebre a un hospital terciario y centros de salud de área entre julio de 2002 y julio de 2018. Se seleccionaron a través de los registros de gotas gruesas o serologías de dengue.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 188 pacientes. El 52,7% habían nacido en España, con edad mediana de 3 años (RIC 1,5-8,0). Las regiones de procedencia del viaje fueron África Sub-Sahariana (54,8%) y Latinoamérica (29,8%). Los motivos principales fueron visitar a allegados (56,3%), seguidos de inmigrantes de llegada reciente (32,4%). Solo el 34% de los viajeros habían realizado consulta pre-viaje. Más del 80% acudieron directamente a Urgencias. Los diagnósticos más frecuentes fueron síndrome febril sin focalidad (56,4%), enfermedad respiratoria (15,4%) y diarrea aguda (11,7%). La mitad (52,1%) fueron dados de alta, pero 46,2% fueron ingresados, y el 7,4% requirió Cuidados Intensivos. No se halló una etiología específica en el 24% de los casos. Sin embargo, el 29,7% tuvieron malaria.

ConclusiónEl síndrome febril en un niño procedente del trópico puede implicar enfermedades graves. Uno de cada cuatro tuvo malaria, y el 7% requirió cuidados intensivos. Por ello, es necesario reforzar la formación en enfermedades tropicales en los médicos de primera línea.

According to the United Nations World Tourism Organization, there were nearly 1400 million international travels in 2017, and tourism has grown at around 4% per year for eight straight years.1 International travelers have grown significantly over the last years, as well as imported diseases from tropical areas. Children may imply up to 10% of travelers.2,3 It is assumed that children are more frequently sick than their caregivers while traveling.4 The commonly named “Visiting Friends and Relatives” (VFR) group acquires special importance as it has been described that VFR children present more probability to travel without pre-travel consultation and proper preventive measures.5 Besides the growth of international travelers, the number of migrants is also increasing.6

Information about medical problems in children coming from the tropics is scarce. Reports are mainly based on single center studies of specific population groups such as admitted patients or travel consultation centers.4,5,7–11 The most frequent consultation reasons are diarrhea, fever and dermatologic complaints, which vary according to regions of origin. Even if they are usually mild common infections, potentially severe and deadly diseases, such as malaria, may underlie a febrile syndrome. Consequently, more studies are required to analyze this specific situation. Our objective is to describe the demographic and clinical characteristics of febrile children coming from the tropics in a tertiary European hospital.

MethodsRetrospective review of patients under 18 years old presenting with fever (axillary temperature≥38°C) at a tertiary Spanish hospital and surrounding primary health care centers, between July 2002 and July 2018, with a stay in a tropical region during the previous year. Due to the absence of a specific diagnostic code in our hospital, patients were selected from microbiological charts of thick smears for malaria or dengue serologies from the Microbiology and Parasitology Department. In all cases in which a thick smear was performed, an immunochromatographic assay was also done (Plasmodium falciparum Histidine Rich Protein II, and pan-malarial antigen detection. BinaxNOW, Alere). Plasmodium species were differentiated doing a thin smear. Additionally, in some cases, realtime polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for detection and differentiation of Plasmodium species (RealStar Malaria Screen & Type PCR Kit 1.0. Altona Diagnostics) was performed. For Dengue testing, an immunochromatographic assay (Dengue Duo, Bioline, SD) for NS1 antigen, IgM and IgG antibodies detection was used.

Data were collected from clinical records and organized attending to five aspects: epidemiology and demographics, travel-related information, Health Care assistance, clinical data and exams performed. Initially diagnosed syndromes were grouped on the 21 groups described by Freedman et al.8 Qualitative variables are shown as percentages, and quantitative variables as median and interquartile range. Chi-squared test and Mann–Whitney U test were used respectively for hypothesis tests. Database was made on Microsoft Access 2013®, with appropriate coding procedure to ensure patient confidentiality. Statistical analysis was performed with IBM® SPSS® Statistics v24. Missing data was not considered into analysis. This study was approved by the local Research and Ethics Committee.

ResultsBetween July 2002 and July 2018, 202 episodes in which thick smears for malaria and/or dengue serologies were performed in children were collected. Fourteen cases did not fulfill the inclusion criteria. Finally, 188 episodes were analyzed, 6 of them corresponded to a second event after another trip in the same patient. Thick smear was performed alone in 157 patients, dengue serology alone in 10 patients, and both tests were done in 21 patients.

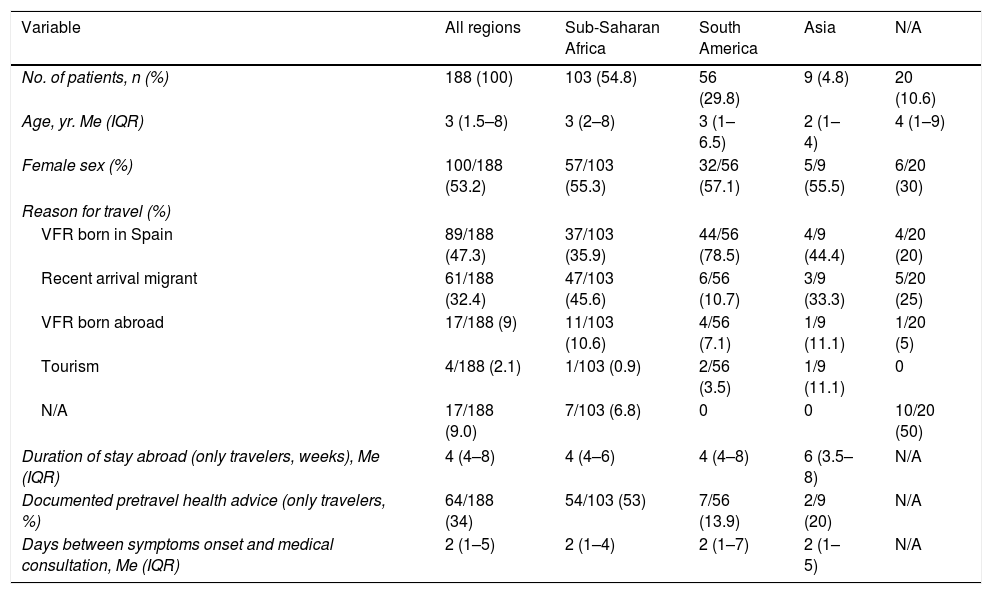

Epidemiology, demographics and travel-related informationHalf of the patients were girls (100/188, 53.2%) and the median age was 3.0 years old (IQR 1.5–8.0). The country of birth was mainly Spain (99/188, 52.7%), followed by Equatorial Guinea (48/188, 25.5%) and Nigeria (4/188, 2.1%). Nevertheless, regarding the ethnic group, the large majority were not Caucasian (182/188, 96.8%), with a predomination of Sub-Saharan African (104/188, 55.3%) and Latin-American (62/188, 33.0%). Demographic characteristics of patients according to visited region are outlined in Table 1.

Characteristics of patients, according to the visited region.

| Variable | All regions | Sub-Saharan Africa | South America | Asia | N/A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients, n (%) | 188 (100) | 103 (54.8) | 56 (29.8) | 9 (4.8) | 20 (10.6) |

| Age, yr. Me (IQR) | 3 (1.5–8) | 3 (2–8) | 3 (1–6.5) | 2 (1–4) | 4 (1–9) |

| Female sex (%) | 100/188 (53.2) | 57/103 (55.3) | 32/56 (57.1) | 5/9 (55.5) | 6/20 (30) |

| Reason for travel (%) | |||||

| VFR born in Spain | 89/188 (47.3) | 37/103 (35.9) | 44/56 (78.5) | 4/9 (44.4) | 4/20 (20) |

| Recent arrival migrant | 61/188 (32.4) | 47/103 (45.6) | 6/56 (10.7) | 3/9 (33.3) | 5/20 (25) |

| VFR born abroad | 17/188 (9) | 11/103 (10.6) | 4/56 (7.1) | 1/9 (11.1) | 1/20 (5) |

| Tourism | 4/188 (2.1) | 1/103 (0.9) | 2/56 (3.5) | 1/9 (11.1) | 0 |

| N/A | 17/188 (9.0) | 7/103 (6.8) | 0 | 0 | 10/20 (50) |

| Duration of stay abroad (only travelers, weeks), Me (IQR) | 4 (4–8) | 4 (4–6) | 4 (4–8) | 6 (3.5–8) | N/A |

| Documented pretravel health advice (only travelers, %) | 64/188 (34) | 54/103 (53) | 7/56 (13.9) | 2/9 (20) | N/A |

| Days between symptoms onset and medical consultation, Me (IQR) | 2 (1–5) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–7) | 2 (1–5) | N/A |

Me: median; IQR: interquartile range; N/A: non-available data.

The most frequent reason for traveling was VFR of children born in Spain (89/188, 47.3%), followed by recently arrived migrants (61/188, 32.4%). Attending to the region in which the children stayed, 54.8% (103/188) came from Sub-Saharan Africa, 29.8% (56/188) from Latin America, and 4.8% (9/188) from Asia. For travelers excluding migrants, the median stay abroad was 4 weeks (IQR 4.0–8.0), and only 34% (64/188) of patients declared having consulted for pre-travel advice. From 188 patients, 149 (79.3%) had arrived to Spain in the previous 3 months, 12 (6.4%) between 3 to 6 months, and in 27 cases (14.4%) information was not available in clinical records.

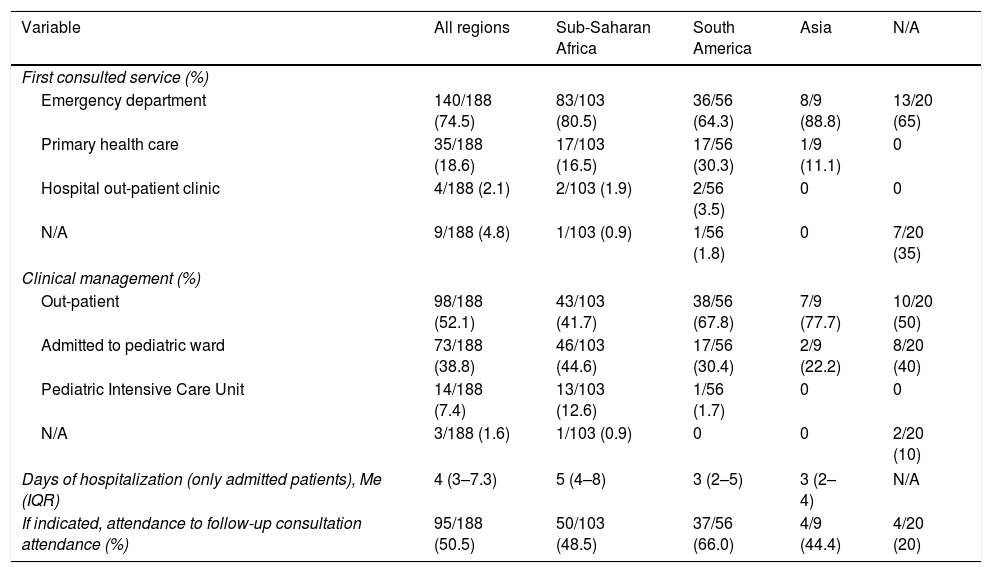

Health care assistanceThe preferred service for first consultation was the hospital Emergency Department (140/188, 74.5%) while less than one fifth of patients attended first to a Primary Health Care center (sending them afterwards to our hospital). Globally, 27 patients (14.4%) had consulted at least once before to another physician without performing a thick smear or dengue serology. Half of the children were managed as out-patients. However, 87 (46.3%) were admitted, and 7.4% (14/188) of them ended up in Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU). Patients from Sub-Saharan Africa were significantly admitted more frequently than those coming from other regions (57.3% vs. 30.8%; p<0.001). The median hospitalization stay was 4 days (IQR 3.0–7.3) (Table 2). One patient (1.2%) died during admission, but it was due to his congenital heart disease and not related to the stay in the tropics.

Health care assistance information.

| Variable | All regions | Sub-Saharan Africa | South America | Asia | N/A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First consulted service (%) | |||||

| Emergency department | 140/188 (74.5) | 83/103 (80.5) | 36/56 (64.3) | 8/9 (88.8) | 13/20 (65) |

| Primary health care | 35/188 (18.6) | 17/103 (16.5) | 17/56 (30.3) | 1/9 (11.1) | 0 |

| Hospital out-patient clinic | 4/188 (2.1) | 2/103 (1.9) | 2/56 (3.5) | 0 | 0 |

| N/A | 9/188 (4.8) | 1/103 (0.9) | 1/56 (1.8) | 0 | 7/20 (35) |

| Clinical management (%) | |||||

| Out-patient | 98/188 (52.1) | 43/103 (41.7) | 38/56 (67.8) | 7/9 (77.7) | 10/20 (50) |

| Admitted to pediatric ward | 73/188 (38.8) | 46/103 (44.6) | 17/56 (30.4) | 2/9 (22.2) | 8/20 (40) |

| Pediatric Intensive Care Unit | 14/188 (7.4) | 13/103 (12.6) | 1/56 (1.7) | 0 | 0 |

| N/A | 3/188 (1.6) | 1/103 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 2/20 (10) |

| Days of hospitalization (only admitted patients), Me (IQR) | 4 (3–7.3) | 5 (4–8) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–4) | N/A |

| If indicated, attendance to follow-up consultation attendance (%) | 95/188 (50.5) | 50/103 (48.5) | 37/56 (66.0) | 4/9 (44.4) | 4/20 (20) |

Me: median; IQR: interquartile range; N/A: non-available data.

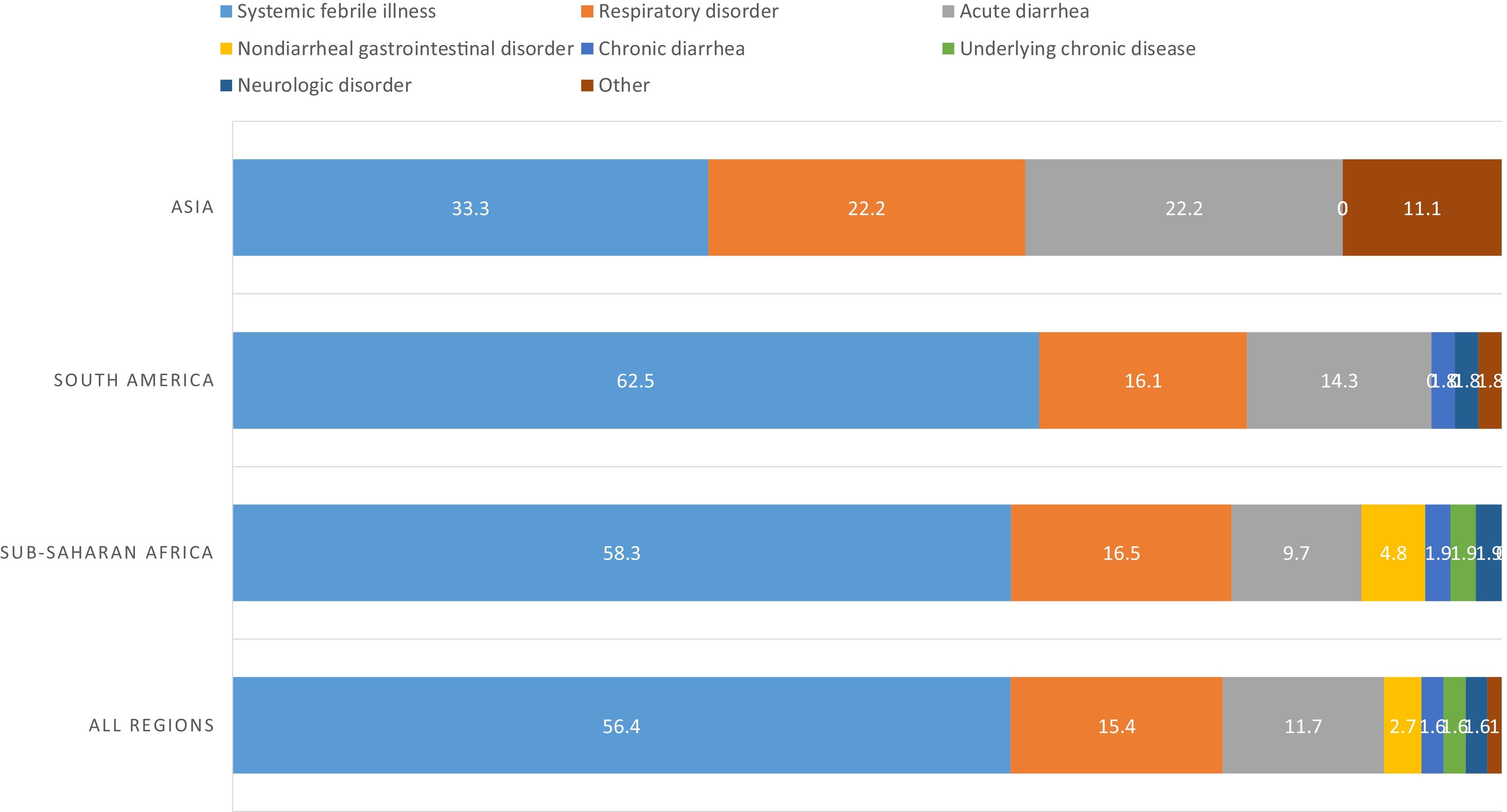

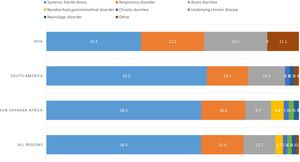

Globally, the main complaint of patients (155/188, 82.4%) was fever (the rest of the patients, though they have had fever, their principal reason for consultation was a different symptom). More than half of patients (106/188, 56.4%) presented a febrile syndrome without source, followed by respiratory tract infections (29/188, 15.4%) and acute diarrhea (22/188, 11.7%). Differences between regions can be seen in Fig. 1.

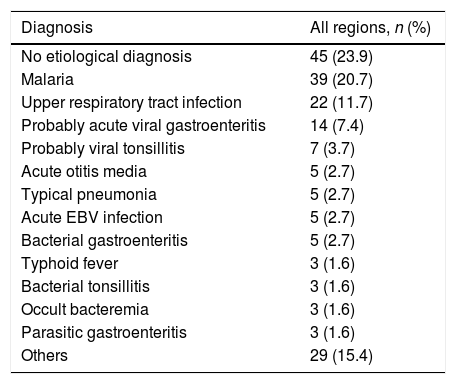

The most frequent final diagnoses are outlined in Table 3. Malaria was the main cause (39/188, 20.7%), though in nearly a quarter of the cases, no specific etiology was identified (45/188, 23.9%). Physical examination was normal in 37.2% (70/188) of patients, but the most common finding was hepatomegaly and/or splenomegaly (33/188, 17.5%). General appearance was only affected (regular or bad) in 20 patients (10.6%). Regarding the 14 patients that were admitted to PICU, 12 had malaria (8 of them had hyperparasitemia as the only severity criteria), 1 had severe dehydration (due to chronic diarrhea in an HIV-infected patient), and in the other one, sepsis was suspected without microbiological confirmation.

Most frequent final diagnoses (n=188).

| Diagnosis | All regions, n (%) |

|---|---|

| No etiological diagnosis | 45 (23.9) |

| Malaria | 39 (20.7) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 22 (11.7) |

| Probably acute viral gastroenteritis | 14 (7.4) |

| Probably viral tonsillitis | 7 (3.7) |

| Acute otitis media | 5 (2.7) |

| Typical pneumonia | 5 (2.7) |

| Acute EBV infection | 5 (2.7) |

| Bacterial gastroenteritis | 5 (2.7) |

| Typhoid fever | 3 (1.6) |

| Bacterial tonsillitis | 3 (1.6) |

| Occult bacteremia | 3 (1.6) |

| Parasitic gastroenteritis | 3 (1.6) |

| Others | 29 (15.4) |

From those 27 patients who had consulted at least once to a physician before performing a thick smear or a dengue serology, almost a half (13 patients, 48,1%) had significant final diagnosis that needed specific management. From these 13 patients, 5 had malaria (18.5%), 2 had pneumonia (7.5%), 2 non-typhi Salmonella bacteremia, 1 dengue fever (3.7%), 1 visceral leishmaniasis, 1 pyelonephritis, 1 Cryptosporidium diarrhea. The other 14 cases (51.9%) had minor diseases.

From the 178 thick smears performed, 39 were positive. Plasmodium falciparum was identified in 34 cases; P. malariae in 2 cases; and there were 3 mixed infections due to P. falciparum-P. malariae, P. falciparum-P. vivax, and P. falciparum-P. ovale. Plasmodium polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed in 25 cases with no discrepancies with thick smear. Median parasitemia at diagnosis was 2.7% (IQR 0.7–6.4%). Median platelet count in patients with malaria was significantly lower than in negative patients, 94×103/μl (IQR 57.5×103/μl−164×103/μl) vs. 284.5×103/μl (IQR 231.5×103/μl−359.3×103/μl), p<0.001. There were no other hematological differences according to malaria diagnosis. Patients in which hepatomegaly or splenomegaly was noted in physical exam, presented more frequently malaria (68.4%) than other diseases (31.5%, p<0.001). There were no coinfections with dengue.

DiscussionFebrile syndrome after a stay in the tropics has been widely studied in adults but in pediatric population information is scarce.9,12,13 Most pediatric publications are focused on specific pathologies and population groups such as admitted patients or travel consultation centers. Moreover, this is the first study to our knowledge done in pediatrics in Spain.

The large majority of our population was Sub-Saharan African and Latin American. Nevertheless, globally, more than a half of children were born in Spain which represents the second generation of migrants, who usually travel to their country of origin (VFR). They represented the main reason for traveling in our study (47.3%). Consequently, most visited regions were Sub-Saharan Africa (54.8%) and Latin America (29.8%). In other studies in children, performed in travel clinics5,8,10 or in Emergency Departments,3,14 tourism is the main reason for traveling, which usually implies shorter lengths of stay and more urban and hygienic destinations than VFRs.5 In our cohort, the median stay in travelers is quite long (4 weeks). Pre-travel advice remains an uncommon practice. Only 34% of patients had previously consulted, which agrees with previously published data.5 In addition, our study presents a considerable group of recent arrival migrants (61 cases, 32.4%), a population less frequently described in reported studies.

Most of the patients chose Emergency Department for the first consultation, and only 35 (18.6%) had contacted before with their primary care practitioner (free of charge in Spain). This rate is lower than the 39.8% described by Naudin et al.,3 probably due to the proportion of recent migrants in our cohort. Globally, 27 patients (14.4%) had consulted previously in Emergency Department, primary health care center, or elsewhere without a thick smear or dengue serology performed while at risk of these diseases. This emphasizes the need for reinforcing the training of first line physicians on this issue. More than half of patients (52.1%) were managed as out-patients and, when admitted, hospitalizations were short. However, some of them presented severe diseases and 14 cases (7.2%) ended up in PICU, mainly for malaria. Hospitalization rate (46.2%) observed was higher than that reported in previous studies on Emergency Departments (20–21%),3,14 possibly because of the patients selection method. Some mild cases in which blood test were not performed may have not been detected and managed as out-patients.

Most of the diagnosed pathologies corresponded to mild and common infections as it is shown in Table 3. Malaria is the first identifiable cause, which has also been reported as the primary cause of febrile syndrome in children and adults.7,8,10 No specific etiology was identified in 23.9% of patients, similar to 20–30% previously published rates in children,3,7 but higher than 8.2–24% adult records.9,15 This highlights the difficulty of the differential diagnosis in children coming from the tropics, where common viral infections are frequent but clinically not very different from infections important to identify, such as malaria. Globally, physical examination was usually normal and general appearance was not altered. Nevertheless, finding hepatomegaly, splenomegaly and bad clinical status were risk factors for admission in pediatric ward or PICU.

Clinical syndromes distribution varies depending on the region of interest. A study from United Kingdom7 showed a predominance of diarrhea, enteric fever and malaria due to P. vivax based mainly on Indian subcontinent patients. In a report from Australian travelers to mainly Southeast Asia and Oceania regions,14 upper respiratory tract infections, systemic febrile illness and diarrhea accounted as the most frequent diagnosis without malaria cases. On the other side, French literature and subgroups of global studies from Sub-Saharan Africa and South-America exhibit a spectrum of diseases closer to our results, with respiratory infections, diarrhea and P. falciparum malaria leading the charts.3,8 However, globally, in most of studies, diarrhea was the main illness,3,5,7,10 while in our study, systemic febrile syndrome, respiratory infections and diarrhea complete the majority of events. In other studies, dermatologic pathology (including sunburn, mosquito bites, etc.) acquires an important place as one of the most frequent diseases after a stay in the tropic.4 In our study, as fever was an inclusion criterion, we only found cases of abscesses.

Malaria was in our study the first individual cause of fever in the child coming from the tropics and the main specific cause of systemic febrile illness, which agrees with previous studies.3,5,8 We found a predominance of P. falciparum, and one third of patients were admitted to PICU (12/39, 30%) for presenting severity criteria. All these patients had satisfactory outcome. PCR for malaria had been performed in 25 cases, with no discrepancies with thick smear and immunocromatographic assay, possibly because of small sample, submicroscopic malaria is rare in children under 5 years old, and that tests were requested based on clinical manifestations such as fever, leaving aside the discrepancies of submicroscopic malaria described.16,17 Lower platelet count was found in patients with malaria, which has been also reported as a comorbidity.7,18

Some limitations may need to be taken into account. First, as there is no specific coding for fever in children coming from the tropics, identification of potential cases was performed using indirect microbiological criteria. This may result in underestimation of the total number of episodes, though these could correspond to trivial infections as probably the severe cases would have frankly manifested. Using thick smear charts may overestimate Sub-Saharan Africa population and malaria prevalence, while little demand for dengue serologies in routine practice may underrepresent patients from South-America and Asia.

ConclusionThe most frequent causes of febrile syndrome in a child coming from the tropics were mild and common infections. However, potential risk of severe diseases such as malaria requires appropriate assessment and a high level of suspicion. Malaria was the main specific cause of fever, and a significant proportion of the patients were admitted to Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Only one third of travelers attended a pre-travel consultation. More than 80% of febrile children coming from the tropics attended directly the Emergency Room and 14.4% had visited another physician previously without any specific tropical assessment. This information emphasizes the need for reinforcing the training about tropical diseases among first line physicians treating children.

FundingNo funding was secured for this study.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.