Education is a cornerstone of antimicrobial stewardships programs, because 50% of inappropriate antimicrobial prescriptions are a consequence of an imbalance between the high levels of knowledge required for the appropriate use of antibiotics and the scarce training offered to medical specialists. For this reason, programs optimizing antimicrobial (PROA) are essentially based on support and educational activities for prescribers. The educational activities are difficult to evaluate. In our country, the application of educational activities in antimicrobial training programs is very heterogeneous, although it has improved in recent years.

We recommend the following educational measures, which are prioritized in order of effectiveness. Interactive educational interventions are the most effective. These are non-compulsory interventions based on real prescriptions in clinical practice and include educational outreach visits, audits and counseling interviews with feedback and multifaceted interventions. Passive educational strategies, with posters, newsletters, and dissemination of guidelines, are only marginally effective in changing antimicrobial prescribing practices and have not shown a sustained effect. These measures need extensive professional involvement and should be combined with more active approaches. Currently, interventions can be enhanced with some teaching tools in electronic format. Both interactive and passive educational measures should be integrated into the PROA and should have institutional support. Finally, we recommend including antimicrobials in the training plans of all clinical specialties.

La educación es la clave de los programas de optimización de antimicrobianos (PROA) porque la consecuencia de que el 50% del uso de antimicrobianos sea inapropiado es la desproporción entre el nivel de conocimientos necesarios para utilizarlos correctamente y la formación específica que reciben los prescriptores. Por esta razón los PROA están basados en actividades educativas. Estas son difíciles de evaluar. En nuestro país, la aplicación de actividades educativas en estos programas, aunque ha mejorado en los últimos años, es muy heterogénea.

Recomendamos las siguientes medidas por orden de efectividad: auditorías, asesorías y visitas académicas como intervenciones basadas en prescripciones reales, con retroalimentación de los resultados e intervenciones multifacéticas. Las estrategias pasivas con difusión de pósters, noticias y guidelinessolo tienen un efecto marginal y temporal en el cambio en la prescripción. Estas medidas necesitan una amplia participación profesional junto con un enfoque más activo y herramientas de enseñanza en formato electrónico. Tanto las medidas interactivas como las pasivas deben integrarse en el PROA y tener el apoyo institucional. Finalmente recomendamos la inclusión de los antimicrobianos en los planes de formación de todas las especialidades clínicas.

Education is a cornerstone antimicrobial stewardships programs (ASP), because 50% of inappropriate antimicrobial prescriptions are the consequence of an imbalance between the high levels of knowledge required for the appropriate use of antibiotics and the scarce training offered to the prescriber.1 For this reason, programs optimizing antimicrobial use (PROAs) are essentially based on support and educational activities for prescribers, and those interested in the development of such programs should be familiar with activities and strategies for continuous medical education.

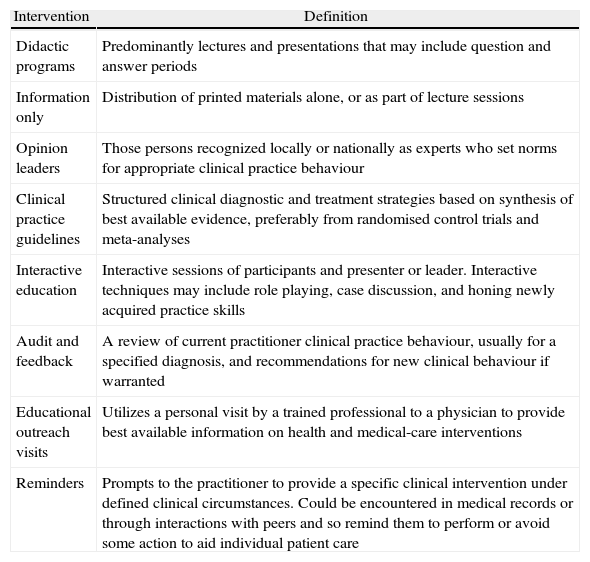

Types of educational activities and interventions in continuous medical educationSince numerous educational activities and interventions have been implemented to improve drug prescription behavior (not all of them tested in antibiotic prescribing), it is important to understand which interventions have been effective. See Table 1 for intervention definitions.

Types of educational activities and definitions2

| Intervention | Definition |

| Didactic programs | Predominantly lectures and presentations that may include question and answer periods |

| Information only | Distribution of printed materials alone, or as part of lecture sessions |

| Opinion leaders | Those persons recognized locally or nationally as experts who set norms for appropriate clinical practice behaviour |

| Clinical practice guidelines | Structured clinical diagnostic and treatment strategies based on synthesis of best available evidence, preferably from randomised control trials and meta-analyses |

| Interactive education | Interactive sessions of participants and presenter or leader. Interactive techniques may include role playing, case discussion, and honing newly acquired practice skills |

| Audit and feedback | A review of current practitioner clinical practice behaviour, usually for a specified diagnosis, and recommendations for new clinical behaviour if warranted |

| Educational outreach visits | Utilizes a personal visit by a trained professional to a physician to provide best available information on health and medical-care interventions |

| Reminders | Prompts to the practitioner to provide a specific clinical intervention under defined clinical circumstances. Could be encountered in medical records or through interactions with peers and so remind them to perform or avoid some action to aid individual patient care |

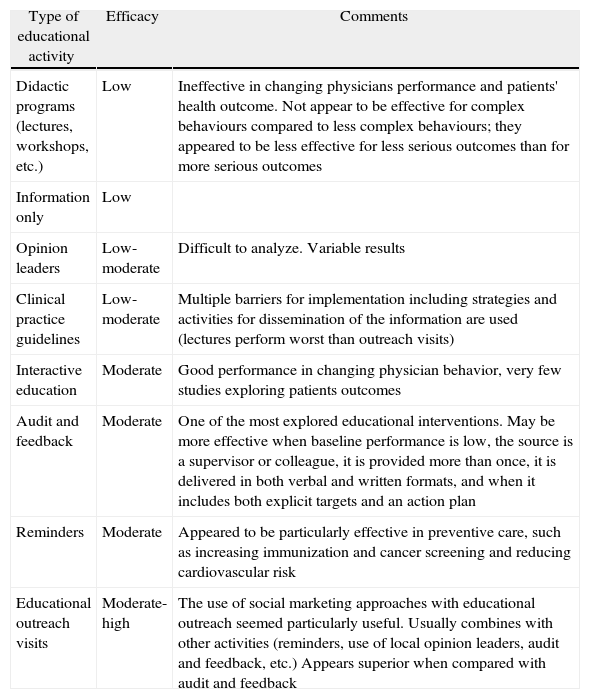

Davey et al described a four-level hierarchy for the evaluation of education: Evaluation of reaction (satisfaction or happiness), evaluation of learning (knowledge or skills acquired), evaluation of behavior (transfer of learning to the workplace) and evaluation of results (transfer to or impact on society).2 It must be noted that the vast majority of educational activities are either not evaluated or are evaluated only to the first or second level. Recent systematic revisions have revealed important differences between educational activities.2–4 Nevertheless, data from studies and systematic reviews in the field of Continuing Medical Education and changing prescription behavior should be interpreted with caution due to the following limitations, among others: a) Most interventions are mixed (e.g., combining different strategies simultaneously); b) there is an influence of baseline performance on results; and c) the results may be influenced by people who implement the activity and by local circumstances (external validity).

Despite these limitations, some general conclusions can be drawn (Table 2). Table 2 shows some evidence that interactive continuing medical education sessions that enhance participant activity and provide the opportunity to practice skills is effective in changing professional practice and, occasionally, health care outcomes. On the other hand, didactic sessions do not appear to be effective in changing physician practices. Finally, some authors have also emphasized that multifaceted interventions were consistently more effective than single interventions.9

| Type of educational activity | Efficacy | Comments |

| Didactic programs (lectures, workshops, etc.) | Low | Ineffective in changing physicians performance and patients' health outcome. Not appear to be effective for complex behaviours compared to less complex behaviours; they appeared to be less effective for less serious outcomes than for more serious outcomes |

| Information only | Low | |

| Opinion leaders | Low-moderate | Difficult to analyze. Variable results |

| Clinical practice guidelines | Low-moderate | Multiple barriers for implementation including strategies and activities for dissemination of the information are used (lectures perform worst than outreach visits) |

| Interactive education | Moderate | Good performance in changing physician behavior, very few studies exploring patients outcomes |

| Audit and feedback | Moderate | One of the most explored educational interventions. May be more effective when baseline performance is low, the source is a supervisor or colleague, it is provided more than once, it is delivered in both verbal and written formats, and when it includes both explicit targets and an action plan |

| Reminders | Moderate | Appeared to be particularly effective in preventive care, such as increasing immunization and cancer screening and reducing cardiovascular risk |

| Educational outreach visits | Moderate-high | The use of social marketing approaches with educational outreach seemed particularly useful. Usually combines with other activities (reminders, use of local opinion leaders, audit and feedback, etc.) Appears superior when compared with audit and feedback |

It is well accepted that education is a cornerstone of any ASP. However, education can vary from passive approaches (posters, newsletters, dissemination of guidelines) to more active activities such as educational outreach visits or interactive educational sessions. Although passive educational strategies are easy to implement, if not combined with more active approaches, they are only marginally effective in changing antimicrobial prescribing practices and have not had a sustained effect.10

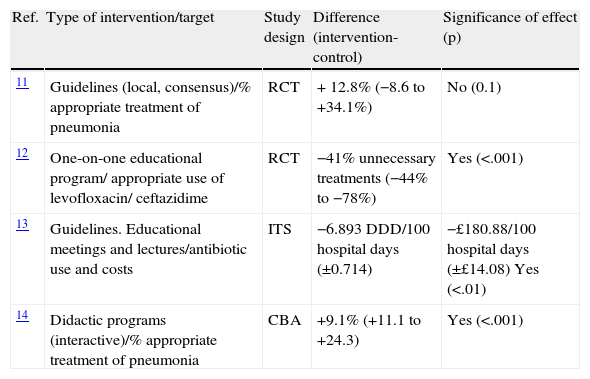

The scarce information regarding the impact of “theoretical didactic” programs (not prescription-based activities) in the field of antimicrobials prescription in hospitals is depicted in Table 3. It confirms the efficacy of interactive educational interventions.

Efficacy of “theoretical-didactic” educational interventions on optimizing antimicrobial prescriptions.

| Ref. | Type of intervention/target | Study design | Difference (intervention-control) | Significance of effect (p) |

| 11 | Guidelines (local, consensus)/% appropriate treatment of pneumonia | RCT | + 12.8% (−8.6 to +34.1%) | No (0.1) |

| 12 | One-on-one educational program/ appropriate use of levofloxacin/ ceftazidime | RCT | −41% unnecessary treatments (−44% to −78%) | Yes (<.001) |

| 13 | Guidelines. Educational meetings and lectures/antibiotic use and costs | ITS | −6.893 DDD/100 hospital days (±0.714) | −£180.88/100 hospital days (±£14.08) Yes (<.01) |

| 14 | Didactic programs (interactive)/% appropriate treatment of pneumonia | CBA | +9.1% (+11.1 to +24.3) | Yes (<.001) |

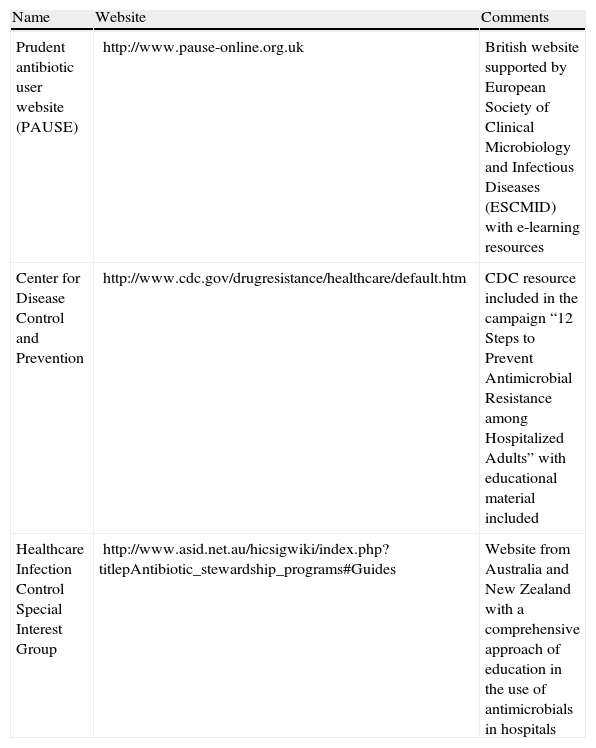

From information derived from other fields of clinical prescription, we could extrapolate that it is possible to optimize the impact of this kind of measure when applied as a part of a multifaceted intervention including other educational measures (such as audits or feedback; see below) and when they are supported by tools such as teaching modules in electronic format.15Table 4 presents some electronic education initiatives in the field of antimicrobial stewardship. Strategies directed toward increasing attendance at educational meetings, using mixed interactive and didactic formats and focusing on outcomes that are likely to be perceived as serious may increase the effectiveness of educational meetings.

Examples of e-learning resources on antimicrobial stewardship.

| Name | Website | Comments |

| Prudent antibiotic user website (PAUSE) | http://www.pause-online.org.uk | British website supported by European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) with e-learning resources |

| Center for Disease Control and Prevention | http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/healthcare/default.htm | CDC resource included in the campaign “12 Steps to Prevent Antimicrobial Resistance among Hospitalized Adults” with educational material included |

| Healthcare Infection Control Special Interest Group | http://www.asid.net.au/hicsigwiki/index.php?titlepAntibiotic_stewardship_programs#Guides | Website from Australia and New Zealand with a comprehensive approach of education in the use of antimicrobials in hospitals |

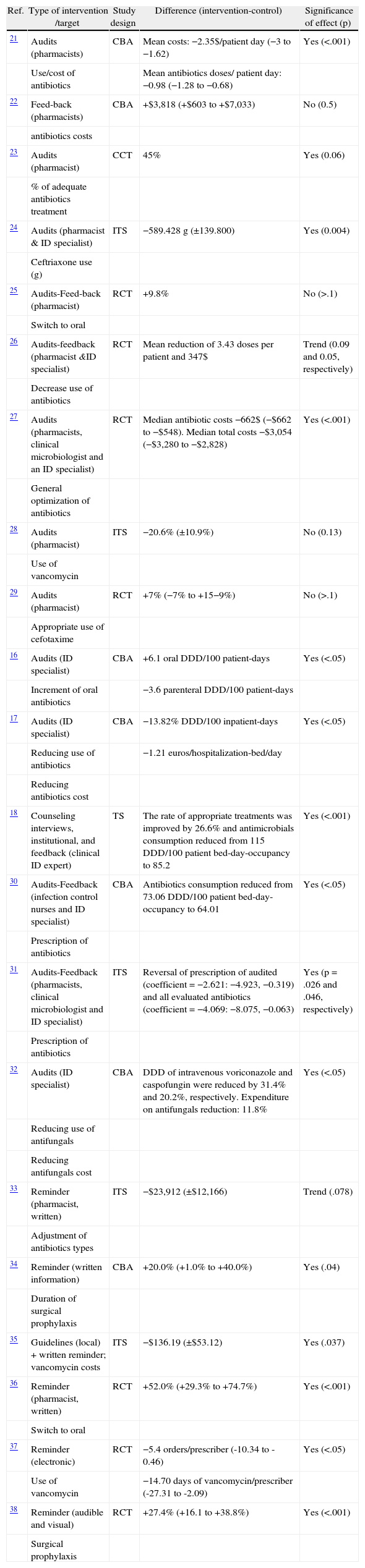

We include here non-compulsory interventions based on real prescriptions in clinical practice, mostly audits and feedback interventions and reminders. In Table 5 we describe the most relevant studies of this type in which the impact on antimicrobials prescription was analyzed.

Efficacy of prescription-based educational interventions on optimizing antimicrobial prescriptions.

| Ref. | Type of intervention /target | Study design | Difference (intervention-control) | Significance of effect (p) |

| 21 | Audits (pharmacists) | CBA | Mean costs: −2.35$/patient day (−3 to −1.62) | Yes (<.001) |

| Use/cost of antibiotics | Mean antibiotics doses/ patient day: −0.98 (−1.28 to −0.68) | |||

| 22 | Feed-back (pharmacists) | CBA | +$3,818 (+$603 to +$7,033) | No (0.5) |

| antibiotics costs | ||||

| 23 | Audits (pharmacist) | CCT | 45% | Yes (0.06) |

| % of adequate antibiotics treatment | ||||

| 24 | Audits (pharmacist & ID specialist) | ITS | −589.428 g (±139.800) | Yes (0.004) |

| Ceftriaxone use (g) | ||||

| 25 | Audits-Feed-back (pharmacist) | RCT | +9.8% | No (>.1) |

| Switch to oral | ||||

| 26 | Audits-feedback (pharmacist &ID specialist) | RCT | Mean reduction of 3.43 doses per patient and 347$ | Trend (0.09 and 0.05, respectively) |

| Decrease use of antibiotics | ||||

| 27 | Audits (pharmacists, clinical microbiologist and an ID specialist) | RCT | Median antibiotic costs −662$ (−$662 to −$548). Median total costs −$3,054 (−$3,280 to −$2,828) | Yes (<.001) |

| General optimization of antibiotics | ||||

| 28 | Audits (pharmacist) | ITS | −20.6% (±10.9%) | No (0.13) |

| Use of vancomycin | ||||

| 29 | Audits (pharmacist) | RCT | +7% (−7% to +15−9%) | No (>.1) |

| Appropriate use of cefotaxime | ||||

| 16 | Audits (ID specialist) | CBA | +6.1 oral DDD/100 patient-days | Yes (<.05) |

| Increment of oral antibiotics | −3.6 parenteral DDD/100 patient-days | |||

| 17 | Audits (ID specialist) | CBA | −13.82% DDD/100 inpatient-days | Yes (<.05) |

| Reducing use of antibiotics | −1.21 euros/hospitalization-bed/day | |||

| Reducing antibiotics cost | ||||

| 18 | Counseling interviews, institutional, and feedback (clinical ID expert) | TS | The rate of appropriate treatments was improved by 26.6% and antimicrobials consumption reduced from 115 DDD/100 patient bed-day-occupancy to 85.2 | Yes (<.001) |

| 30 | Audits-Feedback (infection control nurses and ID specialist) | CBA | Antibiotics consumption reduced from 73.06 DDD/100 patient bed-day-occupancy to 64.01 | Yes (<.05) |

| Prescription of antibiotics | ||||

| 31 | Audits-Feedback (pharmacists, clinical microbiologist and ID specialist) | ITS | Reversal of prescription of audited (coefficient = −2.621: −4.923, −0.319) and all evaluated antibiotics (coefficient = −4.069: −8.075, −0.063) | Yes (p = .026 and .046, respectively) |

| Prescription of antibiotics | ||||

| 32 | Audits (ID specialist) | CBA | DDD of intravenous voriconazole and caspofungin were reduced by 31.4% and 20.2%, respectively. Expenditure on antifungals reduction: 11.8% | Yes (<.05) |

| Reducing use of antifungals | ||||

| Reducing antifungals cost | ||||

| 33 | Reminder (pharmacist, written) | ITS | −$23,912 (±$12,166) | Trend (.078) |

| Adjustment of antibiotics types | ||||

| 34 | Reminder (written information) | CBA | +20.0% (+1.0% to +40.0%) | Yes (.04) |

| Duration of surgical prophylaxis | ||||

| 35 | Guidelines (local) + written reminder; vancomycin costs | ITS | −$136.19 (±$53.12) | Yes (.037) |

| 36 | Reminder (pharmacist, written) | RCT | +52.0% (+29.3% to +74.7%) | Yes (<.001) |

| Switch to oral | ||||

| 37 | Reminder (electronic) | RCT | −5.4 orders/prescriber (-10.34 to -0.46) | Yes (<.05) |

| Use of vancomycin | −14.70 days of vancomycin/prescriber (-27.31 to -2.09) | |||

| 38 | Reminder (audible and visual) | RCT | +27.4% (+16.1 to +38.8%) | Yes (<.001) |

| Surgical prophylaxis |

Audits and feedback interventions are currently the most widely implemented, and there is a great deal of information on evaluations of this modality. According to recently published meta-analyses, audits and feedback interventions applied in general health practice are believed to increase the desired behavior a median of 5% in any trial in which audit and feedback were considered the core, essential aspect of the intervention, compared to those with no audit or feedback.7 Although this median effect may seem relatively small, the 75th percentile effect size is much larger (16% absolute improvement in health professional compliance with desired behavior), suggesting that audit and feedback, when optimally designed and used in the right context, can play an important role in improving professional practice. The most significant practices (as is the case with antimicrobials prescription) are the most likely to be modified by these interventions.7 In general, factors that improve the effectiveness of feedback interventions are low baseline performance, when the source is a supervisor or senior colleague and not an economic manager, when the intervention is provided more than once, when it is provided both verbally and written, and when the intervention includes both measurable targets and an action plan.

When analyzing previous studies focused on the prescription of antibiotics in hospitals, there are differences in reported efficacy data depending on the design of the studies and evaluated outcomes. The aim of most interventions was to optimize therapy either by a) reducing the amount of antibiotic prescribed when it was considered excessive or b) increasing the amount of antibiotic prescribed or improving the timing of administration when these aspects were considered sub-optimal. The study designs were randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials (RCTs/CCTs), controlled before and after studies (CBAs) and interrupted time series (ITSs) studies.

A relevant aspect regarding the efficacy of non-compulsory stewardship audit programs in antimicrobial prescription is acceptance by physicians, which was over 80% in Spain16–18 and in other countries.19,20,39 All these programs show a significant impact on some kinds of antimicrobial prescription compared with historical data, mostly in sequential treatment and when audits are carried out by clinical practitioners such as infectious diseases specialists.

In a systematic review including only RCTs analyzing persuasive audit interventions, it was shown that ten of 14 studies published until 2005 showed a significant intervention effect. In those studies, the differences between the intervention and control groups in terms of the intervention effect ranged from 8% to 69%.2

Specific reminders (written, audible, visual) for specific antimicrobial prescriptions have also been shown to be effective in modifying simple practices such as switching or the duration of surgical prophylaxis, as is shown in Table 5. There is scarce evidence regarding the application of such tools to more complex antimicrobial prescriptions.

What is the current situation of education on the use of antimicrobials in our hospitals?In Spain, while there have been institutional campaigns to improve the non-hospital use of antimicrobials, real recommendations on the need for antibiotic optimization programs in hospitals did not appear until the last four or five years. There is also little information on the characteristics and distribution of this type of activity.

Two of the first published studies in our country on Programs for Optimizing the use of Antibiotics (PROA) were those by Cobo Reinoso et al.16 and López-Medrano et al.17 Cobo et al carried out an interventional study of two hospital departments (medical and surgical) to look at antibiotic costs, mortality rates, readmissions following infectious disease, and the incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Clostridium difficile between the intervention period and the same period in the previous year. A total of 101 antimicrobial therapy courses administered to 80 patients were evaluated. Eighty-five percent of the recommendations were accepted. No changes, either in the mortality rate or the readmission rate due to infectious diseases, were observed. In contrast, a decrease in the incidence of both MRSA and C. difficile was observed. The authors concluded that the advice of an infectious diseases specialist was well accepted and resulted in a decrease in antibiotic costs by simplifying antibiotic therapies without a negative impact on patients’ outcomes.16

In the study by López Medrano et al.,17 the results of a non-compulsory program for the assessment and control of antibiotic treatment were shown. The program was applied in the hospitalization units of six medical and surgical departments. Treatments for all patients were checked daily and recommendations were made in writing according to previously established criteria. The program was used for 12 months and the results were compared with those of the previous 12 months. A total of 1,280 treatments were reviewed and 524 recommendations were made (80% were accepted). They found that antibiotic prescriptions improved and expenditures decreased, with no change in the length of hospital stay or mortality. There was a reduction in the incidence of some nosocomial infections. Acceptance of the program by the physicians of the departments involved was favorable.

Several similar studies on adults were later published by Spanish researchers.18,40–42 In the study by Arco et al.,41 276 interventions including a multidisciplinary non-compulsory counseling program for antimicrobial management were described. The authors evaluated the adequacy of empirical treatment, the possibility of antibiotic de-escalation, the duration and dose used, the evolution of the sensitivity profile of the main microorganisms, and they carried out a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ninety percent of the recommendations were accepted. Their conclusion was that non-compulsory counseling programs were useful tools for the optimization of antimicrobial therapy, can prevent an increase in antimicrobial resistance, and can reduce the cost of antibiotic treatment.

Fariñas et al.42 recently published a prospective, randomized, one-year study in which patients received intravenous antimicrobial therapy prescribed by physicians for 3 days. Patients were identified and randomized into intervention (the use of written infectious diseases (ID) recommendations in clinical records) or non-intervention groups. The appropriateness of empirical treatments (by treating physicians) was classified as adequate, inadequate or unnecessary. In the intervention group, adherence to recommendations was classified as complete, partial or non-adherent. A total of 1173 patients were included, 602 in the non-intervention and 571 in the intervention group. Among the patients in the intervention group, 199 (34.9%) completely adhered to the recommendations, 141 (24.7%) partially adhered and 231 (40.5%) did not adhere. Their main conclusion was that adherence to ID recommendations by treating physicians was associated with favorable outcomes and shorter hospitalizations.

In a study to be published this year, Cisneros et al.,18 found that the implementation of an education-based ASP achieved a significant improvement in all antimicrobial prescriptions of the center (+25.6% appropriate prescriptions) and a reduction in antimicrobial consumption (–29.8 DDD/100 occupied bed-days), even when no restrictive measures were implemented, and the program was highly accepted by all prescribers (97%). The main activity of the program consists of a training program directed towards all antibiotic prescribers of the center and is based on counseling interviews.

In addition to the studies carried out in specific centers, there has been only one study performed in our country on activities for the improvement of the use of antibiotics and the perceptions of the professionals.43 In this study, Paño-Pardo JR et al. conducted an online survey between September 15 and November 23, 2009 and distributed through the e-mailing lists of several working groups of the Spanish Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Society (SEIMC). The survey had the following objectives: a) to describe the frequency, distribution and characteristics of activities of optimization of use of antibiotics in Spanish hospitals; and b) to describe the perceptions of Spanish infectious disease professionals on this type of activity. Surveys representing 78 hospitals were received and analyzed. Most of the respondents were either ID physicians (30%) or microbiologists (29%). Their conclusions were that only 40% of the surveyed hospitals in Spain had ongoing antimicrobial stewardship activities and that there were large geographical variations. The majority of interventions were carried out on de-escalation, sequential therapy and monitoring. It is noteworthy that a large proportion of hospitals carried out these activities without a structured program and without institutional support. Antimicrobial stewardship activities were most commonly delivered by an integrated, part-time multidisciplinary team of ID physicians and pharmacists and in their study, carbapenems were considered the antibiotic most in need of monitoring.

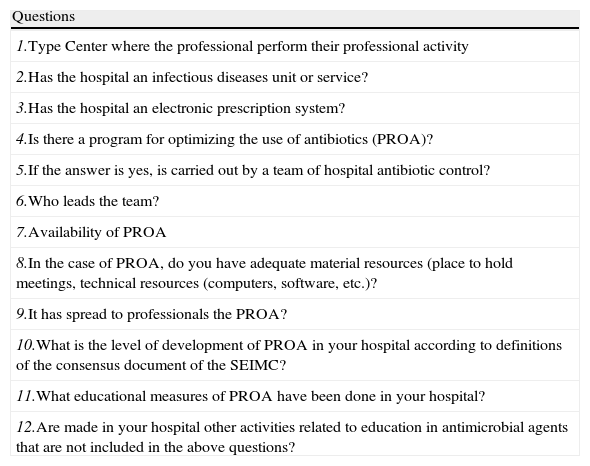

For this review, a survey was sent to all professionals involved in this monograph in January 2013, to describe the current situation regarding PROA in selected Spanish hospitals. A survey of 12 questions (Table 6) was sent via e-mail to professionals at 17 centers.

Programs for optimizing the use of antibiotics (PROA) in Spain. Survey.

| Questions |

| 1.Type Center where the professional perform their professional activity |

| 2.Has the hospital an infectious diseases unit or service? |

| 3.Has the hospital an electronic prescription system? |

| 4.Is there a program for optimizing the use of antibiotics (PROA)? |

| 5.If the answer is yes, is carried out by a team of hospital antibiotic control? |

| 6.Who leads the team? |

| 7.Availability of PROA |

| 8.In the case of PROA, do you have adequate material resources (place to hold meetings, technical resources (computers, software, etc.)? |

| 9.It has spread to professionals the PROA? |

| 10.What is the level of development of PROA in your hospital according to definitions of the consensus document of the SEIMC? |

| 11.What educational measures of PROA have been done in your hospital? |

| 12.Are made in your hospital other activities related to education in antimicrobial agents that are not included in the above questions? |

Of the 17 hospitals in 11 (65%) had implemented a PROA. Of these, 63% had between 500 and 1,000 beds, 18% more than 1000 beds and another 18% less than 500 beds. Six hospitals had not implemented a PROA, and of those 4 had more than 1000 beds and 2 between 500 and 1,000 beds.

Sixteen of the 17 hospitals have an ID service/unit and an electronic prescription system. Surprisingly the hospital without an ID unit has implemented a PROA. Of the 11 hospitals in which a PROA has been implemented, in 10 this program is carried out by a team, which in addition to an ID specialist includes Microbiology (72%), Pharmacy (72%), Preventive Medicine (27%), Intensive Care (27%) and Pediatrics (9%) specialists. In the majority of cases (54%), the PROA is available only in the morning, in 36% of cases in the morning and evening and in 9% the 24 hours. Ninety percent of hospitals with PROA have adequate material resources (e.g., a place to hold meetings, technical resources including computers and software, etc.) and have been used some methods to publicize the program such as an annual antibiotics education course, empirical treatment guidelines, hospital general sessions, individualized meetings with units or departments, etc.

According to the definitions of the Consensus Document of the SEIMC (Basic, Advanced or Excellent),44 most centers have achieved either a basic level (45%) or advanced (36%). One center did not answer. No center had an excellent level. All the centers with PROA perform educational measures in the hospital, using local guidelines and/or clinical pathways or active training interventions. These active interventions include: daily audits with advice on anti-infective treatment, counseling interviews, occasional and informal consultations at the time of the intervention, and daily sessions of positive cultures.

These findings have a significant bias because the survey was conducted in hospitals whose professionals had been previously chosen for participation in this monograph and thus the results should be taken with caution. In view of these data, it can be concluded that much work remains to be done. The current concern about this topic is a great opportunity to expand the implementation of optimization antibiotic programs as a tool for improvement of antibiotic use in the hospitals of our country.

Recommendations for educational measures for the use of antimicrobials in Spanish hospitalsCurrently, 50% of antimicrobial prescriptions are inappropriate,45 and it is likely due to an imbalance between the high level of knowledge required for the appropriate use of antibiotics, and the scarce training offered in this respect to practicing clinicians in our country.1 For these reasons, PROAs are essentially based on support and educational activities for prescribers.

We recommend interactive educational interventions, based on real prescriptions in clinical practice. These include educational outreach visits, audits and counseling interviews with feedback and multifaceted interventions. Passive educational strategies alone, with posters, newsletters, and dissemination of guidelines, are only marginally effective in changing antimicrobial prescribing practices. Both interactive and passive educational measures should be integrated into the PROA and should have institutional support. Finally, antimicrobials should be included in the training plans of all clinical specialties

Conflicts of interestJMC has received speaking honoraria from MSD, Astellas, Novartis and Pfizer.

All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank all the authors of this monograph for their collaboration in our survey.