Human cryptosporidiosis, an infection caused by parasitic protozoan of the genus Cryptosporidium, is a major cause of gastrointestinal disease worldwide including Spain.1 Most human cases are attributed to C. hominis and C. parvum, although infections with zoonotic C. meleagridis, C. canis, C. felis, and a number of rare genotypes are also sporadically documented.2 Among these, Cryptosporidium cuniculus (previously known as the Cryptosporidium rabbit genotype) was first identified in an adult female rabbit in 19793 and fully re-described and characterized in 2010.4 Since then, very few cases of human infections by C. cuniculus have been identified in UK (n=37),5 Nigeria (n=5),6 Australia (n=1),7 and France (n=1).8

In May 2015 a 7-year-old female child complaining of gastrointestinal symptoms including acute, non-bloody watery diarrhoea and abdominal pain, was admitted to the outpatient clinic of the University Hospital Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda (Madrid) for routine coproparasitological examination. The patient had a normal immune status and no relevant record of recent travelling abroad. Information regarding contact with pet or wild rabbits was unavailable. A single, concentrated stool sample tested positive for the presence of Cryptosporidium oocysts by a commercial immunochomatographic test (Cer Test Biotec S.L., Zaragoza, Spain) and by microscopic examination of a fresh faecal smear stained with the modified Ziehl–Neelsen method.

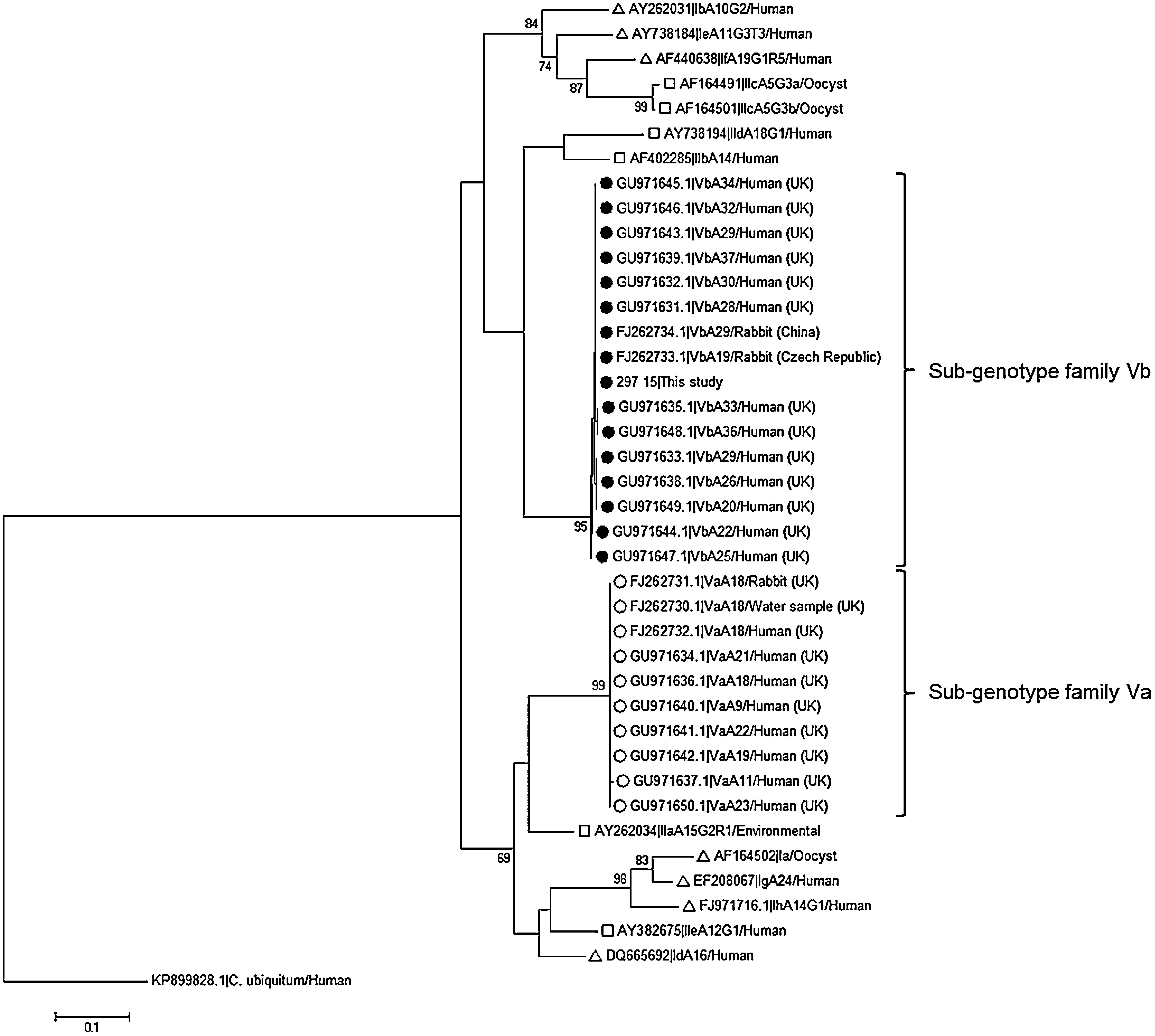

A new aliquot of the faecal material was sent to the National Centre for Microbiology at Majadahonda (Madrid) for genotyping analyses. Total DNA was extracted and purified using the QIAamp® DNA stool mini test kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Identification and molecular characterization of the obtained isolate was conducted by multilocus genotyping (involving PCR-based protocols and DNA sequence analyses) of the small-subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA)9 and the 60-kDa glycoprotein (GP60)10 genes of Cryptosporidium. Both SSU rRNA-PCR and GP60-PCR assays generated the expected amplicons of ∼587bp and ∼870bp, respectively. Sequence analysis of the corresponding PCR products confirmed the presence of C. cuniculus, allowing the assignment of this isolate to the sub-genotype VbA34 of the parasite. As expected, phylogenetic analysis at the GP60 locus between the sequence from this study and reference sequences previously deposited in GenBank placed our isolate into a well-defined allelic group (family Vb), while other representative sub-genotypes of C. cuniculus clustered together in a separate allelic group (family Va) (Fig. 1). The nucleotide sequence data obtained in this study at the SSU rRNA and the GP60 loci have been deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers KU129015 and KU129016, respectively.

Phylogenetic relationships between Cryptosporidium cuniculus and Cryptosporidium spp. sub-genotypes at the GP60 locus inferred by a neighbour-joining analysis of the nucleotide sequence covering a 445-bp region (positions 1 to 445 of GenBank accession number GU971645, allele VbA34) of the gene. Empty and filled circles indicate representative C. cuniculus sequences belonging to the sub-genotype families Va and Vb, respectively. Empty triangles and squares indicate representative sequences of the most frequent sub-genotypes of C. hominis and C. parvum, respectively. Bootstrapping values over 50% from 1000 replicates are indicated at the branch points. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Kimura 2-parameter method. The rate variation among sites was modelled with a gamma distribution (shape parameter=2). C. ubiquitum was used as outgroup taxa.

This paediatric case represents the first report of cryptosporidiosis by C. cuniculus in Spain. To date C. cuniculus has been almost exclusively found in rabbits and humans. This fact is hardly surprising when considering that this Cryptosporidium species is genetically closely related to C. hominis, from which it differs in only 0.27% of base pairs. However, deep morphological and biological differences have been demonstrated between both species.4 In UK C. cuniculus was first identified as a human pathogen of zoonotic origin during a waterborne outbreak in July 2008, being the third most commonly identified Cryptosporidium species in clinical patients during the period 2007–2008. Contrasting with the typical distribution patterns of C. hominis and C. parvum, C. cuniculus cases were detected in individuals of all ages with a seasonal peak in late summer and autumn.5

Taken advantage of the inherent genetic heterogeneity of the GP60 gene two different families (Va and Vb) have been described within C. cuniculus, each containing at least seven and 12 different sub-genotypes, respectively.4,5 Sub-genotypes within these allele families were assigned on the basis of the number of TCA serine codons present in the microsatellite region of the gene. In this regard, the C. cuniculus isolate obtained in this study was characterized as sub-genotype VbA34, sharing 100% homology with the sequence of a human isolate from UK (GenBank accession number GU971645). Although the actual origin of the C. cuniculus infection in our paediatric patient could not be investigated, direct contact with pet or wild rabbits seems the most likely source of infective oocysts. Therefore, good personal hygiene practices, especially hand washing, are highly advisable when handling rabbits or their faecal material.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

This study was funded by the Carlos III Institute of Health, Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness under projects CP12/03081 and PI13/01103.