Audits for monitoring the quality of antimicrobial prescribing are a main tool in antimicrobial stewardship programs; however, interobserver reliability has not been conclusively assessed. Our objective was to measure the level of agreement between pharmacists and physicians on the appropriateness of antimicrobials prescribing in hospitals.

MethodsA national multicenter, cross-sectional study was conducted of patients who were receiving antimicrobials one day of April 2021. Hospital participation was voluntary, and the study population was randomly selected. Pharmacists and physicians performed a simultaneous, independent assessment of the quality of antimicrobial prescriptions. The observers used an assessment method by which all indicators of the quality of antimicrobial use were considered. Finally, an algorithm was used to rate overall antimicrobial prescribing as appropriate, suboptimal, inappropriate, or not assessable. Gwet's AC1 coefficient was used to assess interobserver agreement.

ResultsIn total, 101 hospitals participated, and 411 hospital antimicrobial prescriptions were reviewed. The strength of agreement was moderate regarding the overall quality of prescribing (AC1=0.51; 95%CI=[0.44–0.58]). A very good level of agreement (AC1>0.80) was observed between pharmacists and physicians in all indicators of the quality, except for duration of treatment, rated as good (AC1=0.79; 95%CI=[0.75–0.83]), and registration on the medical record, rated as fair (AC1=0.34; 95%CI=[0.26–0.43]). The agreement was greater in critical care, onco-hematology, and pediatric units than in medical and surgery units.

ConclusionsIn this point prevalence study, a moderate level of agreement was observed between pharmacists and physicians in the evaluation of the appropriateness of antimicrobials prescribing in hospitals.

Las auditorías para evaluar la calidad de las prescripciones antibióticas son una herramienta fundamental en los Programas de Optimización del Uso de Antimicrobianos, sin embargo, la concordancia entre evaluadores no ha sido valorada de forma concluyente. El objetivo fue medir el nivel de acuerdo entre farmacéuticos y médicos en la evaluación de la adecuación de las prescripciones antibióticas en hospitales.

MétodosEstudio multicéntrico, transversal en pacientes hospitalizados que recibieron antibióticos un día de abril de 2021. La participación de los hospitales fue voluntaria, y los pacientes seleccionados aleatoriamente. Farmacéuticos y médicos evaluaron la adecuación de las prescripciones de forma simultánea e independiente utilizando una metódica de evaluación que consideraba indicadores implicados en la calidad del uso de los antibióticos. Finalmente se usó un algoritmo para calificar la prescripción como adecuada, mejorable, inadecuada y no valorable. Se utilizó el coeficiente Gwet's AC1 para valorar la concordancia entre evaluadores.

ResultadosParticiparon 101 hospitales y se revisaron 411 prescripciones antibióticas. El acuerdo fue moderado en la calificación global de la prescripción (AC1=0,51; 95%CI=[0,44-0,58]). Se alcanzó un nivel de acuerdo muy bueno (AC1>0,80) en todos los indicadores de calidad, excepto la duración del tratamiento, valorado como bueno (AC1=0,79; 95%CI=[0,75-0,83]), y el registro en la historia clínica, valorado como moderado (AC1=0,34; 95%CI=[0,26-0,43]). El acuerdo fue mayor en unidades de críticos, oncohematología y pediatría que en unidades médicas y quirúrgicas.

ConclusionesEste estudio de prevalencia registró un nivel de acuerdo moderado entre farmacéuticos y médicos en la evaluación de la adecuación de prescripciones antibióticas en hospitales.

Auditing the quality of antimicrobial prescribing, otherwise said, evaluating its appropriateness, is essential in antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASP) at all levels of healthcare.1,2 Although a variety of indicators have been proposed to assess the quality of antimicrobial use,3–7 a standardized assessment method has not yet been established.

Assessing the quality of antimicrobial prescribing requires a longitudinal approach, given that antimicrobial management is a dynamic process that may change throughout the course of treatment. However, since longitudinal studies are challenging and expensive to conduct, cross-sectional studies are often chosen. This type of study, when carried out in a large sample, provides snapshots of the entire course of antimicrobial treatment.8–12

A challenge when evaluating antimicrobial prescribing is that all indicators of the quality of antimicrobial use must be considered, including indication, agent choice, dose, route and time of administration, and duration of treatment. However, standard categories of appropriateness for all quality indicators and the weight of each indicator in the overall quality assessment have not been established.13 A cross-sectional multicenter study, the PAUSATE study, was recently conducted in Spain to evaluate the appropriateness of antimicrobial prescribing in hospitals. This study was based on an algorithm that included all these quality indicators and rated overall prescribing as appropriate, suboptimal, inappropriate, or not assessable.14

Another unresolved issue is the level of specialization and training required for evaluators. This aspect is especially relevant, as their criteria are critical in the face of the uncertainties that surround the diagnosis and treatment of infectious diseases and the absence of objective evaluation standards. The professional training and subjectivity of the observer interfere in the process of evaluating the quality of antibiotic prescribing, but its impact on inter-rater reliability has not been convincingly measured.15,16

The objective of this study was to determine the level of agreement between pharmacists and physicians when evaluating the quality of antimicrobials prescribing in hospitals through a multicenter cross-sectional study.

Material and methodsDesign and patientsAn observational, multicenter, cross-sectional study in adult and pediatric patients hospitalized in Spanish hospitals in April 2021. The project was an extension of the PAUSATE study, which purpose was to determine the prevalence and appropriateness of hospital use of antimicrobials.14

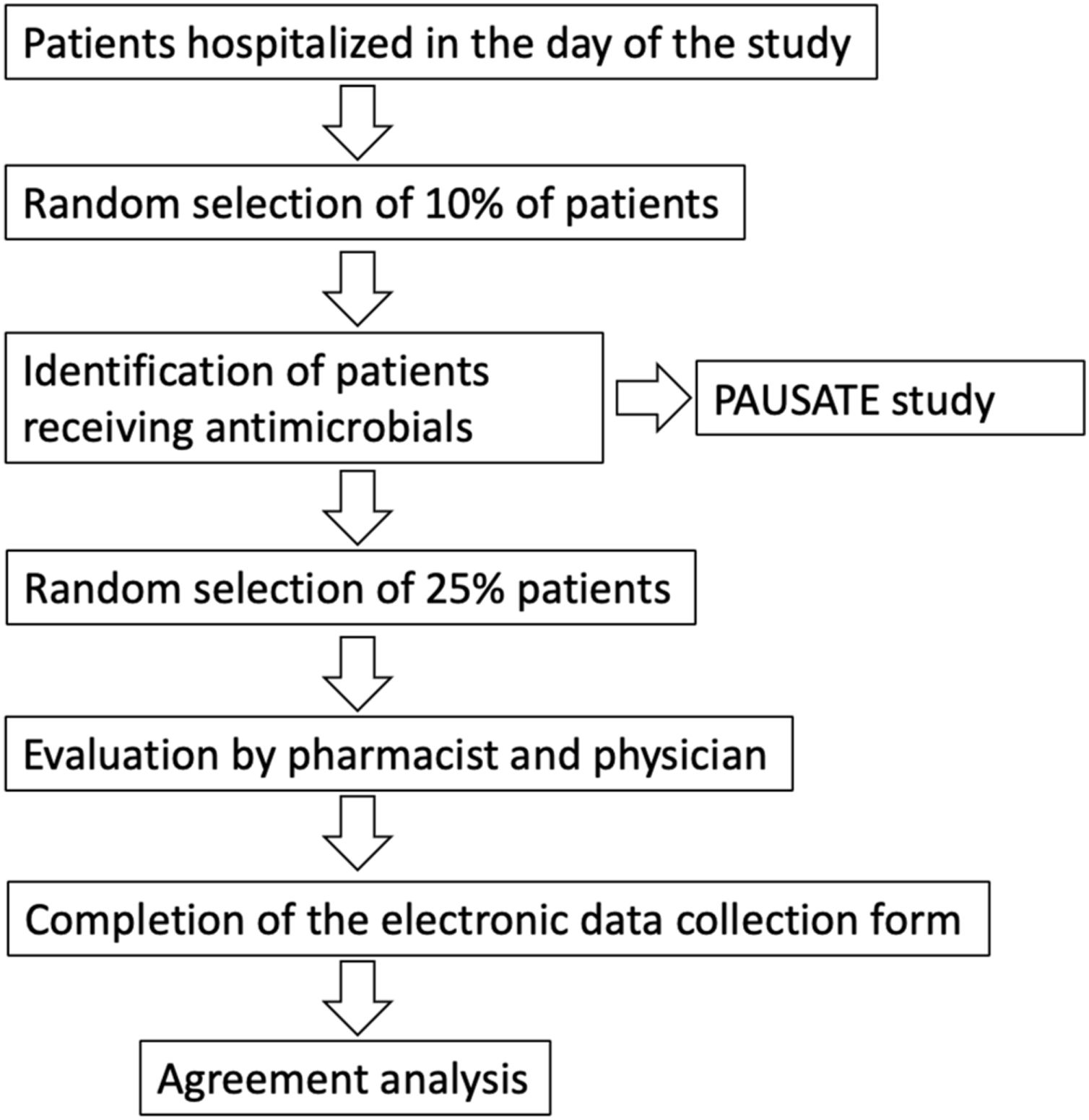

Hospitals were invited to voluntarily participate in the study through the email list of the members of the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacy. One pharmacist and one medical researchers with clinical experience in antimicrobial therapy were selected from each center. The participating hospitals chose a date within the study period to carry out the prevalence study. Thus, 10% of the patients hospitalized in the whole hospital on that date, whatever the clinical unit, were randomly selected.

The pharmacist at each center disaggregated the selected patients, who had received at least an antimicrobial corresponding to ATC codes J01, J02, J04, J05AB, J05AD and J05AH of the anatomical therapeutic classification,17 on the selected date and carried out and evaluation of the appropriateness of the treatment in the PAUSATE study.

On a second stage conducted simultaneously, 25% of the prescriptions evaluated by the pharmacist were randomly selected for evaluation by the study physician. Therefore, the final sample for the evaluation of interobserver reliability was 25% of the patients who received antibiotics, selected in turn from 10% of the patients hospitalized in the day of the study (Fig. 1). Evaluation between pharmacists and physicians was done blindly. Finally, the level of agreement between pharmacists and physicians was assessed.

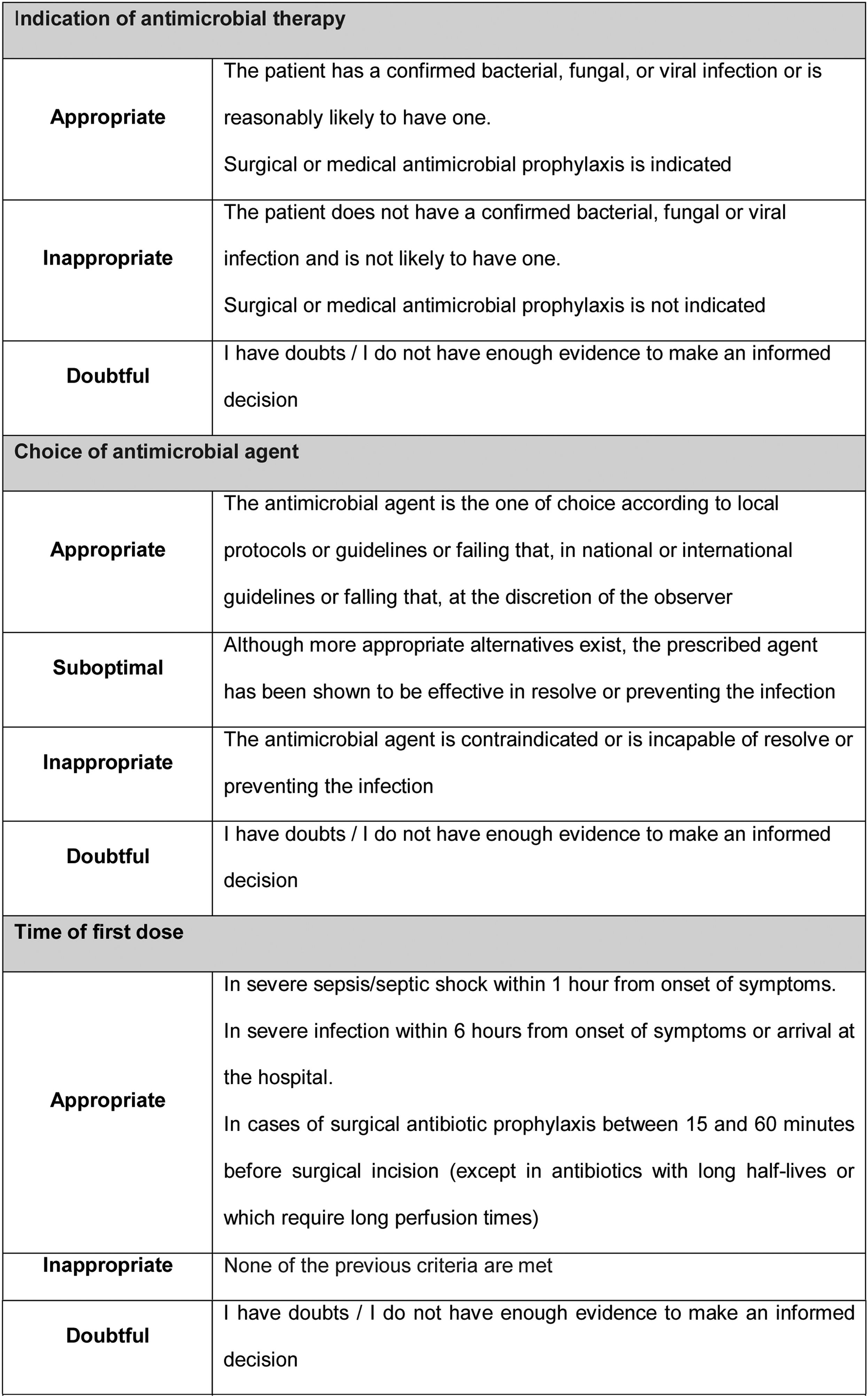

Prescription evaluation methodPharmacists and physicians evaluated the appropriateness of the treatment following the AFinf method. By this method, the quality of antimicrobial prescribing is assessed using indicators of the quality of antimicrobial use in hospitals described in the literature (Fig. 2).3–6

A cross-sectional evaluation of all quality indicators was carried out, except for duration of treatment, which was evaluated after antimicrobial therapy was completed. The two evaluations were preferably carried out the same day as patient selection or, failing that, in the following days, so that the evaluator had the same clinical and microbiological information as the prescriber.

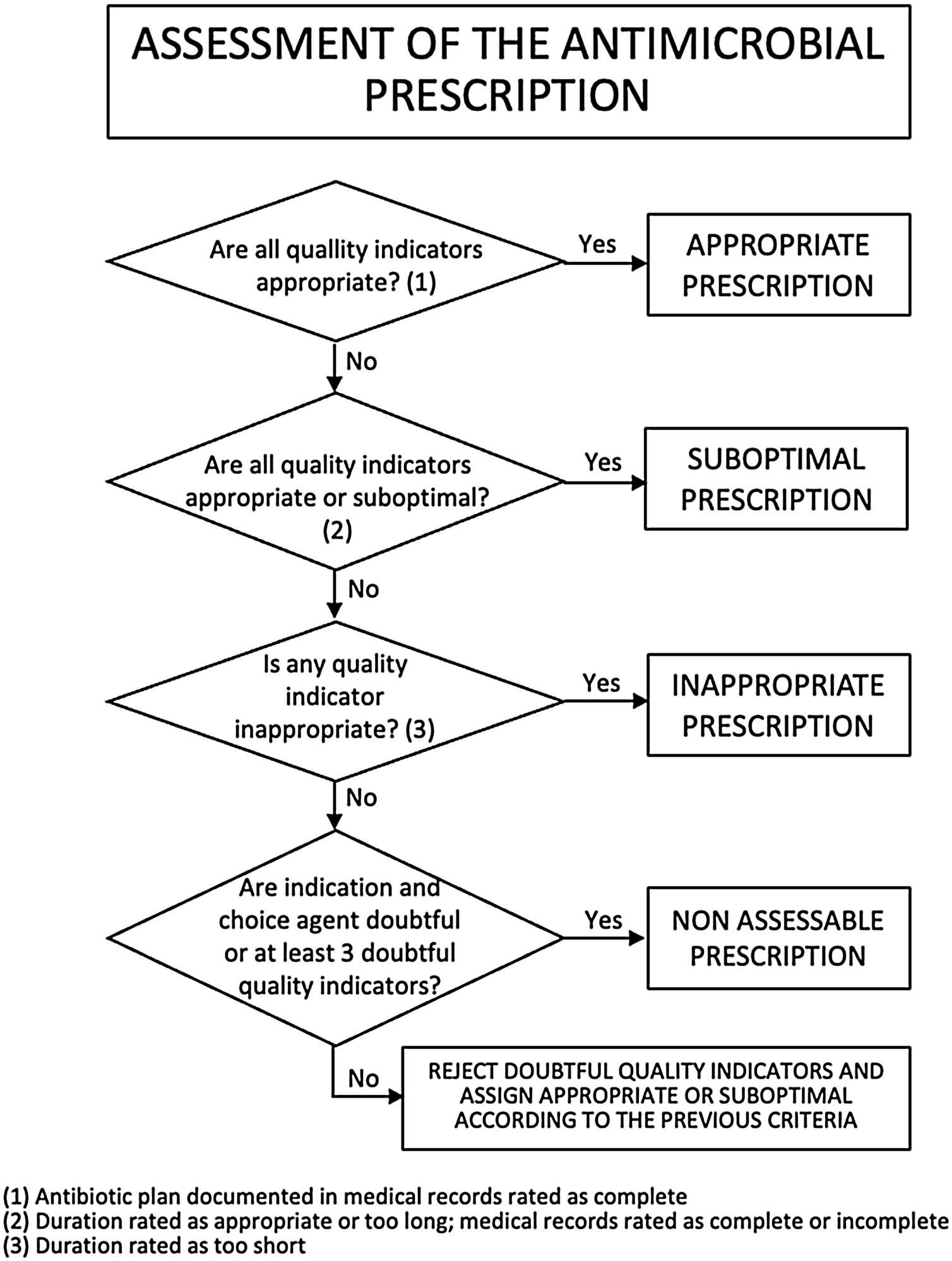

Criteria for rating a prescription according to quality indicatorsOverall, a prescription was considered appropriate if all quality indicators were rated as appropriate (antibiotic plan documented in medical record rated as complete); suboptimal if all quality indicators were rated as appropriate or suboptimal (duration of treatment rated as appropriate or too long and antibiotic plan documented in medical record rated as complete or incomplete); or inappropriate if any quality indicator was rated as inappropriate (duration of treatment rated as too short). If a prescription contained two or fewer doubtful ratings, its rating as appropriate, suboptimal, or inappropriate did not change. If it contained 3 or more doubtful ratings or simultaneously indication for antimicrobial therapy and agent choice doubtful, it was classified as non-assessable, except if some indicators were rated as inappropriate or duration of treatment was rated as too short, in which case the prescription was considered inappropriate (Fig. 3).

Data collectionData was extracted from patient medical records and, when necessary, by contacting the prescribing physician. The variables collected for each patient were sex, age, treating clinical unit, active antimicrobial agent(s), and pharmacist's and physician's rating of each indicator. Data was collected and entered into a spreadsheet using the electronic data capture tools of REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture).18

Ethical issuesThe study was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee accredited at national level. The Committee decided that patient informed consent was not required. Each participating center agreed to participate after having received information about the study design and method. The researchers did not receive any compensation for their work. Prescribers were contacted personally, if the evaluators considered that the prescription may have had negative effects on the patient.

Statistical analysisData was analyzed using STATA software version 15.0. Simple descriptive statistics were applied for the analysis of demographic and clinical variables. The linear weights analysis and Gwet's coefficient were applied to calculate the level of agreement. Values were interpreted as proposed by Landis & Koch, who distinguished five levels of agreement: poor (less than 0.20), fair (0.21–0.40), moderate (0.41–0.60), good (0.61–0.80), and very good (0.81–1.00).19 The use of the Kappa coefficient was ruled out due to its paradoxical effect in high prevalences.20 The Wald Chi-squared test was applied to measure differences in the level of agreement between subgroups of patients. A major discrepancy was defined as when one of the evaluators rated a quality indicator as appropriate and the other as inappropriate or vice versa, or in the duration of treatment, one evaluator rated it as appropriate and the other too short or vice versa.

ResultsA total of 101 hospitals distributed heterogeneously over Spain participated in the study. By size, 39 hospitals had more than 500 beds; 27 between 200 and 500 beds; and 35 had less than 200 beds.

A review was performed of antimicrobial prescriptions for 411 patients (60.3% men), with a median age of 66 years (range: 0–101). In total, 195 patients (47.5%) were treated in a medical unit; 135 (32.8%) in a surgery unit; 34 (8.3%) in an onco-hematology unit; 32 (7.8%) in a critical care unit; and 12 (2.9%) in a unit of pediatrics, whereas three patients (0.7%) were treated in other units.

Of the 411 patients, 400 (97.3%) received at least one antibacterial, 34 (8.3%) at least one antifungal, and 16 (3.9%) at least one antiviral. Combination therapy was prescribed to 129 patients (31.4%). A total of 161 patients (39.2%) received an agent with activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa (anti-pseudomonal beta-lactam, fluoroquinolone, aminoglycoside or polymyxin), 59 patients (14.3%) an agent with activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (glycopeptide, oxazolidinone, daptomycin, or tigecycline; there were no prescriptions for cephalosporins with activity against MRSA). Of these patients, 37 (9.0%) received concomitant agents with activity against both microorganisms.

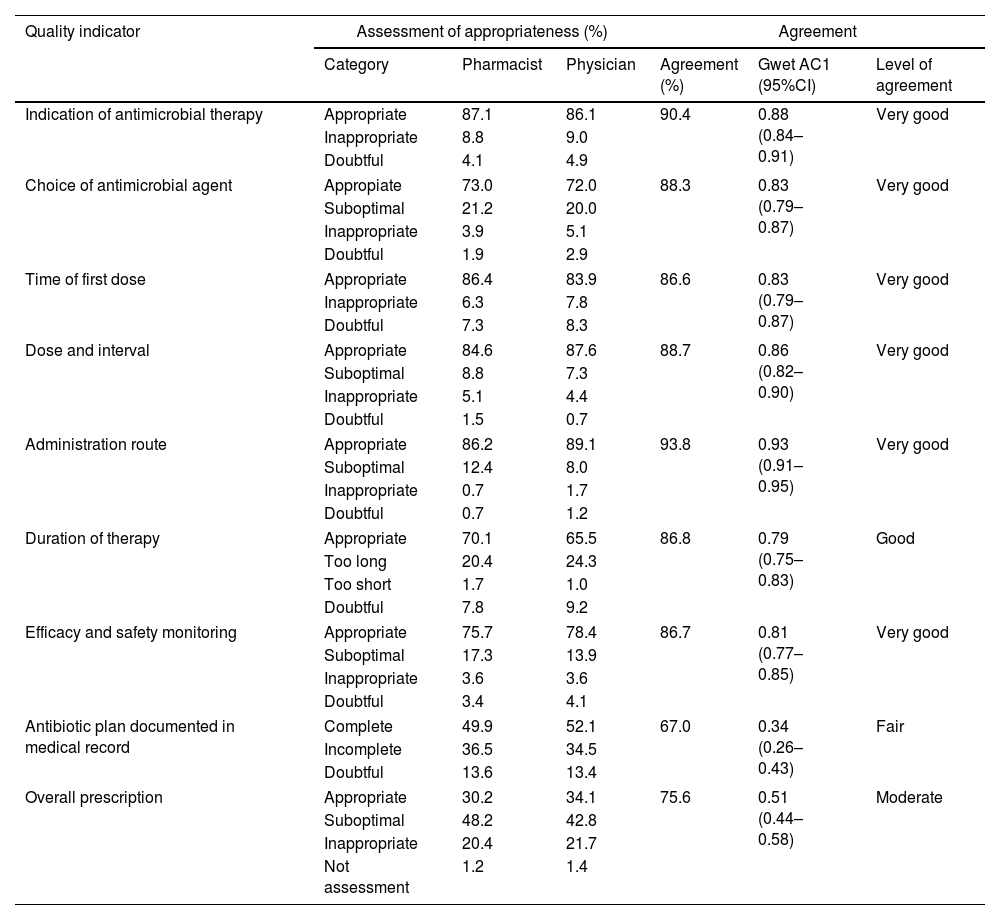

Table 1 shows the level of appropriateness after pharmacists and physicians assessed all indicators and the overall quality of antimicrobial prescribing. Pharmacists and physicians gave similar scores of appropriateness to each category of indicators, with a maximum difference of 5.4%. The level of interobserver agreement is also shown in Table 1.

Assessment of appropriateness and level of agreement between pharmacists and physicians.

| Quality indicator | Assessment of appropriateness (%) | Agreement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Pharmacist | Physician | Agreement (%) | Gwet AC1 (95%CI) | Level of agreement | |

| Indication of antimicrobial therapy | Appropriate | 87.1 | 86.1 | 90.4 | 0.88 (0.84–0.91) | Very good |

| Inappropriate | 8.8 | 9.0 | ||||

| Doubtful | 4.1 | 4.9 | ||||

| Choice of antimicrobial agent | Appropiate | 73.0 | 72.0 | 88.3 | 0.83 (0.79–0.87) | Very good |

| Suboptimal | 21.2 | 20.0 | ||||

| Inappropriate | 3.9 | 5.1 | ||||

| Doubtful | 1.9 | 2.9 | ||||

| Time of first dose | Appropriate | 86.4 | 83.9 | 86.6 | 0.83 (0.79–0.87) | Very good |

| Inappropriate | 6.3 | 7.8 | ||||

| Doubtful | 7.3 | 8.3 | ||||

| Dose and interval | Appropriate | 84.6 | 87.6 | 88.7 | 0.86 (0.82–0.90) | Very good |

| Suboptimal | 8.8 | 7.3 | ||||

| Inappropriate | 5.1 | 4.4 | ||||

| Doubtful | 1.5 | 0.7 | ||||

| Administration route | Appropriate | 86.2 | 89.1 | 93.8 | 0.93 (0.91–0.95) | Very good |

| Suboptimal | 12.4 | 8.0 | ||||

| Inappropriate | 0.7 | 1.7 | ||||

| Doubtful | 0.7 | 1.2 | ||||

| Duration of therapy | Appropriate | 70.1 | 65.5 | 86.8 | 0.79 (0.75–0.83) | Good |

| Too long | 20.4 | 24.3 | ||||

| Too short | 1.7 | 1.0 | ||||

| Doubtful | 7.8 | 9.2 | ||||

| Efficacy and safety monitoring | Appropriate | 75.7 | 78.4 | 86.7 | 0.81 (0.77–0.85) | Very good |

| Suboptimal | 17.3 | 13.9 | ||||

| Inappropriate | 3.6 | 3.6 | ||||

| Doubtful | 3.4 | 4.1 | ||||

| Antibiotic plan documented in medical record | Complete | 49.9 | 52.1 | 67.0 | 0.34 (0.26–0.43) | Fair |

| Incomplete | 36.5 | 34.5 | ||||

| Doubtful | 13.6 | 13.4 | ||||

| Overall prescription | Appropriate | 30.2 | 34.1 | 75.6 | 0.51 (0.44–0.58) | Moderate |

| Suboptimal | 48.2 | 42.8 | ||||

| Inappropriate | 20.4 | 21.7 | ||||

| Not assessment | 1.2 | 1.4 | ||||

The level of agreement was very good in all quality indicators, except for duration of treatment, rated as good, and for documentation of the antimicrobial plan on the medical record, rated as fair. A moderate level of agreement was found in the assessment of the overall quality of prescribing.

The percentages of major discrepancies by quality indicator were: indication of antimicrobial therapy: 6.1%, choice of antimicrobial agent: 2.7%, time of first dose: 8.8%, dose and interval: 5.6%, administration route: 0.5%, duration of therapy: 1.9%, and efficacy and safety monitoring: 3.2%. A 6.6% of major discrepancy was found in the overall prescription.

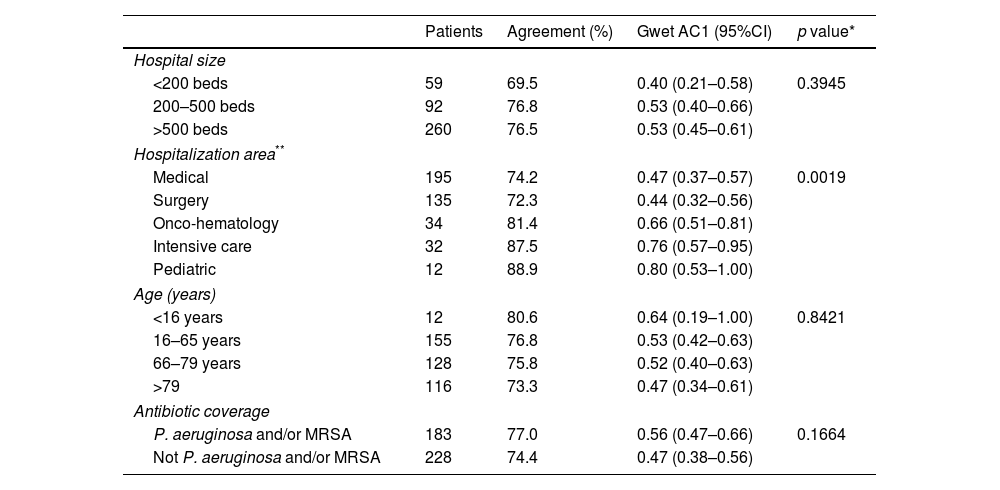

No differences were observed in the level of agreement between pharmacists and physicians when considering prescriptions of patients distributed by hospital size, age and spectrum of the prescribed antimicrobial. However, differences were found when compared by hospitalization area, so that in critical care, onco-hematology and pediatric units the agreement was greater than in medical and surgery units (Table 2).

Agreement by subgroups in overall prescription.

| Patients | Agreement (%) | Gwet AC1 (95%CI) | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital size | ||||

| <200 beds | 59 | 69.5 | 0.40 (0.21–0.58) | 0.3945 |

| 200–500 beds | 92 | 76.8 | 0.53 (0.40–0.66) | |

| >500 beds | 260 | 76.5 | 0.53 (0.45–0.61) | |

| Hospitalization area** | ||||

| Medical | 195 | 74.2 | 0.47 (0.37–0.57) | 0.0019 |

| Surgery | 135 | 72.3 | 0.44 (0.32–0.56) | |

| Onco-hematology | 34 | 81.4 | 0.66 (0.51–0.81) | |

| Intensive care | 32 | 87.5 | 0.76 (0.57–0.95) | |

| Pediatric | 12 | 88.9 | 0.80 (0.53–1.00) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| <16 years | 12 | 80.6 | 0.64 (0.19–1.00) | 0.8421 |

| 16–65 years | 155 | 76.8 | 0.53 (0.42–0.63) | |

| 66–79 years | 128 | 75.8 | 0.52 (0.40–0.63) | |

| >79 | 116 | 73.3 | 0.47 (0.34–0.61) | |

| Antibiotic coverage | ||||

| P. aeruginosa and/or MRSA | 183 | 77.0 | 0.56 (0.47–0.66) | 0.1664 |

| Not P. aeruginosa and/or MRSA | 228 | 74.4 | 0.47 (0.38–0.56) | |

In our study, the level of agreement between pharmacists and physicians in relation to the appropriateness of antimicrobial prescriptions was very good in all indicators that define the quality of antimicrobial use, except for the duration of treatment, rated as good, and documentation of the antimicrobial plan on the medical record, rated as fair. According to the designed algorithm, the level of inter-rater agreement on the overall quality of prescribing was moderate.

To the best of our knowledge, few studies have evaluated the reliability of audits for monitoring the quality of antimicrobial prescribing. The studies found in the literature are mostly single-center studies with heterogeneous designs and methods that include a small sample and exclude some clinical units, which limits the generalization of results.21–28 These studies assessed the level of agreement between experts from one or several specialties on adherence to therapeutic guidelines and protocols; others assessed compliance with indicators of the quality of antimicrobial use, with disparate results that do not provide a general picture of practice.

Our approach was unique in several aspects. Firstly, it is a multicenter study including a large sample that does not exclude any hospital specialty. Secondly, it is based on an evaluation method that considers all indicators of the quality of antimicrobial use in hospitals. In addition, the study uses an algorithm that combines these indicators to determine the overall quality of antimicrobial prescribing.

The only indicator of the quality of antimicrobial prescribing that did not reach an acceptable level of inter-rater agreement was the reason for start, change or discontinue the antimicrobial treatment described on patient's record. This indicator is the one that is subjected to a greater degree of subjectivity because the criteria of each observer are different to consider the use of the antimicrobial in the medical records as justified. Stewardship programs recommend that the clinical management plan, the antimicrobial treatment selected, and the indication and duration of treatment must be included on patient's record.4,29 This strategy helps physicians reflect on their therapeutic decisions and facilitates the review of antimicrobial treatments.

In addition, a moderate level of agreement was found in the rating of the overall quality of prescribing. This is explained by the reduction of the effect, as overall rating depends on the fulfillment of all quality indicators. However, the level of agreement did not increase after the exclusion of the indicator with the worst rating, i.e., the documentation of the antibiotic plan in the medical record, from the overall prescription appropriateness rating algorithm (AC1=0.49; 95%CI=[0.42–0.56]).

The quality indicator with the highest percentage of major discrepancies, although it only accounts for 8.8% of the prescriptions, was the time of administration of the first dose, even though the definition of the indicator clearly established the times for each score. We think that it may be because the evaluators did not judge the situation of sepsis or severe infection of the patient identically or that the time of administration could not be verified exactly in the medical records.

Interestingly, the level of interobserver agreement did not decrease in prescriptions for subgroups of complex patients, such as elderly patients, inpatients of large hospitals, and patients receiving antibiotics with coverage for P. aeruginosa and/or MRSA. The agreement was higher in critical care, onco-hematology and pediatric units compared to medical and surgical units. The reason for this difference has not been studied, but we think that it may be because in the first units there may be a greater degree of protocolization of antimicrobial therapies, which translates into less subjectivity in the evaluation and, consequently, greater agreement between observers.

The audit and feedback with face-to-face educational interventions providing unsolicited antibiotic advice are interventions described in antimicrobial stewardship programs.1,2 Knowing objectively the quality of the use of antibiotics is the first step to improve their use. The strength of this work is to demonstrate that with the audit method used, a moderate degree of agreement is reached between observers in the evaluation of antibiotic prescriptions. Undoubtedly, a greater degree of agreement would be desirable to consolidate the validity of the audit tool, and strategies that could favor this would be to have a local antimicrobial therapeutic guideline and the training of the evaluators.

Our study has several limitations. In the first place, although voluntary participation enabled a heterogeneous distribution, with a greater weight of large hospitals, it may have led to a selection bias; thus, the centers participating in the study presumably have a greater motivation for the adequate use of antimicrobials. Another selection bias is that only patients receiving at least one antimicrobial were included in the study, whereas patients with an indication of antimicrobial therapy who remained untreated were excluded.

Another limitation refers to the small sample of patients included per center, an average of 4 patients, with up to 20 centers contributing only with one patient; however, the study design favored massive participation of hospitals, thereby reducing the workload in each center.

In conclusion, our cross-sectional multicenter study applied an established evaluation method by which all indicators of the quality of antimicrobial use are considered and revealed a moderate level of agreement between pharmacists and physicians on the appropriateness of antimicrobial prescribing.

Authors’ contributionsConception and design of the study: José María Gutiérrez-Urbón.

Writing of the manuscript: José María Gutiérrez-Urbón.

Critical review of the study: José María Gutiérrez-Urbón, Eva Campelo-Sánchez, Sara Cobo-Sacristán, Marcelo Domínguez-Cantero, María Victoria Gil-Navarro, Sonia Luque, María Eugenia Martínez-Núñez, Beatriz Mejuto, Francisco Moreno-Ramos, Leonor Periañez-Párraga, Carmen Rodríguez-González, Teresa Rodríguez-Jato.

Approval of the final version for publication: José María Gutiérrez-Urbón, Eva Campelo-Sánchez, Sara Cobo-Sacristán, Marcelo Domínguez-Cantero, María Victoria Gil-Navarro, Sonia Luque, María Eugenia Martínez-Núñez, Beatriz Mejuto, Francisco Moreno-Ramos, Leonor Periañez-Párraga, Carmen Rodríguez-González, Teresa Rodríguez-Jato.

FundingThe study does not have any subsidy or payment from a public or private entity. Neither authors nor collaborators have received fees for their work.

Transparency declarationsAll authors: none to declare.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

The authors acknowledge all participating pharmacists and physicians for assessing the quality of antimicrobial prescriptions (Appendix A).

The authors thank María Isolina Santiago Pérez for her assistance in statistical analysis.