To review the incidence and characteristics of acute hepatitis B (AHB) in a large cohort of HIV infected persons from a low prevalence region during the last two decades.

MethodsRetrospective review of an HIV Cohort from a single reference centre in Madrid, Spain, between 2000 and 2018. AHB was diagnosed in persons with newly acquired HBAgS and acute hepatitis with positive IgM anti-HBc.

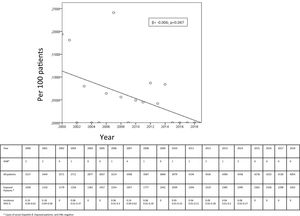

ResultsOut of 5443 HIV+ patients in our cohort (3098 anti-HBc negative), 18 developed AHB from 2000 to 2018. The global incidence was 0.02 (0.01–0.04) per 100 patient-year in the entire population and 0.06 (0.01–0.1) per 100 patient-year in the anti-HBc negative population. A statistically significant decrease in AHB incidence was observed during these years (β=−0.006; p=0.047).

All 18 patients diagnosed with AHB were men, the majority (16) occurred in men who have sex with men. AHB was observed in 4 persons previously unresponsive to vaccination. Regarding antiretroviral treatment (ART), 15 were not receiving ART, two persons were on ART with any HBV active drugs and one person had lamivudine in the regimen. Two persons (11%) developed chronic hepatitis B. There were no cases of fulminant hepatitis.

ConclusionThe incidence of AHB in HIV positive persons in our cohort was low and shows a progressive decline in the last 20 years. Cases occurred in persons not protected against VHB: not vaccinated or non-responders to vaccine that were not receiving tenofovir.

Revisar la incidencia y las características de la hepatitis B aguda (HAB), en pacientes infectados por VIH en seguimiento durante las dos últimas décadas.

MétodosRevisión retrospectiva de los casos de HAB en la cohorte de pacientes infectados por VIH y seguimiento en el Hospital Universitario La Paz, entre los años 2000 y 2018. La HAB se definió como la reciente aparición del AgS frente al virus de la hepatitis B (VHB) y anticuerpos anti-HBc+ de tipo IGM.

ResultadosSe siguieron 5.443 pacientes VIH+, de ellos, 3.098 sin contacto previo con el VHB (anti-HBc negativo). Diagnosticamos 18 casos de HAB, lo que supone una incidencia de 0,02 (0,01-0,04) por 100 pacientes-año en toda la población y 0,06 (0,01-0,1) por 100 pacientes-año en aquellos anti-HBc negativo. Observamos una disminución significativa en la incidencia a lo largo de los años (β = -0,006; p = 0,047).

Los 18 pacientes eran hombres y la mayoría (16) tenían sexo con hombres. En cuatro casos, la HAB se produjo en pacientes vacunados sin respuesta. Quince pacientes estaban sin tratamiento frente al VIH (TAR), dos recibían TAR sin drogas frente al VHB y uno tenía TAR con lamivudina, pero no tenofovir. No observamos ninguna hepatitis B grave, pero dos pacientes (11%) desarrollaron una hepatitis crónica B.

ConclusiónLa incidencia de la HAB en pacientes VIH+ en nuestro hospital es baja y ha disminuido en los últimos 20 años. Aun así, seguimos viendo casos en pacientes sin protección para el VHB: sin vacunar o vacunados sin respuesta, que no reciben tenofovir.

In Spain, the recommendation for hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccination initially started in 1982 targeting high-risk groups (which included HIV infected persons). Over the next decades, the Spanish National Health System expanded HBV vaccine recommendations in order to achieve universal immunization, and, since 2002, all neonates born in Spain ought to receive complete HBV vaccination.1 Therefore, HBV incidence rate has declined during the last decade to rates between 1 and 1.5 cases per 100,000 persons-year.2

In HIV infected persons, the incidence of acute hepatitis B (AHB) may have also decreased with the widespread use of HBV vaccination, but also since the inclusion of antiretroviral treatments (ART) that are effective against HBV such as tenofovir, emtricitabine or lamivudine. However, data of AHB in this population are lacking. HIV infected persons are a vulnerable population for acute viral hepatitis,3–5 firstly because HBV and HIV mechanisms of transmission and secondly because the immune response to HBV vaccination is reduced in HIV-infected subjects.6

The objective of our study was to analyze the incidence and factors associated with AHB in a large cohort of HIV positive patients in Spain.

MethodsRetrospective analysis of an HIV Cohort from a single reference centre in Madrid, Spain. AHB was defined as persons who developed an acute hepatitis (increase in transaminase levels) with positive IgM VHB core antibody (anti-HBC). All patients should have had a previous negative anti-HBC IGG. Previous serology, history of HBV vaccination, epidemiological and clinical characteristics, as well as HIV related factors were recorded and analyzed. Incidence of AHB was calculated with the number of cases of AHB related to the entire population and with the number of cases related to persons without prior HBV exposure (HBcAb negative). Evolution to chronic hepatitis B was considered when HBsAg persisted at least 6 months after de AHB diagnosis.

Data are given as absolute number and percentage for categorical variables and as median (range) for continuous variables. Incidences are given with its 95% confidence intervals. A linear regression analysis was performed to study changes in annual incidence.

ResultsOverall, 5443 HIV infected persons were followed in our cohort since the year 2000: 2345 (43%) had a positive anti-HBc (reflecting past or present HBV infection), while 3098 persons were susceptible for AHB. Between 2000 and 2018, there were 18 cases of AHB. The incidence of AHB in the entire population was 0.02 (0.01–0.04) per 100 patient-year and 0.06 (0.01–0.1) per 100 patient-year in persons without past HBV exposure. The annual incidence in not previously exposed showed a decrease during the study period: from 0.19 (0.04–0.62) per 100 patients in 2000 to 0 cases from year 2015 to 2018; β=−0.006; p=0.047 (Fig. 1). The highest incidence was 0.24 (0.09–0.62) per 100 patients, in the year 2007.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 18 AHB cases. All cases of AHB occurred in men, with a median age of 32 years (17–45), the majority (16) were diagnosed in men who have sex with men (MSM), with two cases of intravenous drugs users. Half of the persons with AHB were Spanish (9/18, 50%), the remainder were mostly from Latin-American origin (8/18, 44.4%). Only three patients had a previous diagnosis of liver disease (chronic hepatitis C in the three cases) but none of them had advance liver fibrosis. Hepatitis Delta coinfection was not diagnosed in any case. Related to immune status, 14 patients had never been vaccinated against HBV and 4 had received vaccination but without response. Overall, 15 persons (83.3%), were not receiving ART at the time of AHB diagnosis, in 4 cases the diagnosis of HIV and AHB was simultaneous. None of the patients were on treatment with tenofovir, two persons were receiving ART with drugs without activity against VHB and one person was treated with lamivudine as part of his ART. In two persons (11%) AHB became chronic HBV infection. There were no cases of fulminant hepatitis.

Characteristics of 18 persons with acute hepatitis B diagnosis.

| Patient | Year of diagnosis | Sex | AGE | TR | Country | Previous HBV vaccination | ART | Evolution to chronic infection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2000 | Male | 36 | MSM | Spain | No | D4T-3TC-NFV | No |

| 2 | 2000 | Male | 41 | MSM | Colombia | No | No | Yes |

| 3 | 2001 | Male | 33 | MSM | Spain | Yes | D4T-DDI-IDV | No |

| 4 | 2001 | Male | 29 | IDU | Spain | No | No | No |

| 5 | 2003 | Male | 17 | MSM | Ecuador | No | No | No |

| 6 | 2006 | Male | 33 | MSM | Ecuador | No | No | No |

| 7 | 2007 | Male | 26 | IDU | Guinea E. | No | No | No |

| 8 | 2007 | Male | 44 | MSM | Spain | No | No | Yes |

| 9 | 2007 | Male | 26 | MSM | Spain | Yes | No | No |

| 10 | 2007 | Male | 30 | MSM | Spain | No | No | No |

| 11 | 2008 | Male | 31 | MSM | Peru | No | No | No |

| 12 | 2010 | Male | 36 | MSM | Spain | Yes | No | No |

| 13 | 2011 | Male | 35 | MSM | Spain | No | Noa | No |

| 14 | 2012 | Male | 30 | MSM | Venezuela | No | No | No |

| 15 | 2012 | Male | 37 | MSM | Colombia | No | Noa | No |

| 16 | 2013 | Male | 30 | MSM | Argentina | No | Noa | No |

| 17 | 2014 | Male | 45 | MSM | Mexico | Yes | ETV/RAL | No |

| 18 | 2014 | Male | 32 | MSM | Spain | No | Noa | No |

The incidence of AHB in our cohort of HIV positive persons was 0.02 per 100 patient-years. This is much higher than what has been reported in the Spanish general population since the year 2000 (between 0.001 and 0.002 per 100 person-year).1,2 We give data of incidence in the entire population in order to compare with other population based studies that don’t separate patients previously exposed to HBV. However, we believed, incidence rate in anti-HBC negative patients (0.06 per 100 patients-year) was also of interest, as these are the real patients on risk for acquiring AHB. It is known that the HIV infected population, due to shared routes of transmission and lower rates of HBV vaccine response, should be considered as a high risk group for having a HBV infection.6 Our results confirm this data and highlight the importance of vaccination in our routine clinical practice, mainly in young MSM that come from countries without universal vaccine implementation programmes. In our cohort all cases were seen in young men, mainly MSM and half of them were immigrants. Likewise, in Spain, the highest incidence of AHB in the last years was seen in men between 35 and 65 years of age.2 HBV vaccination would be more efficacious if it is given in young MSM irrespectively of HIV status because nearly in a quarter of our cases AHB and HIV were simultaneously diagnosed.

HIV infected persons have a lower rate of immune response to HBV vaccine.6 Lower response rates have been associated with lower CD4 cell counts and detectable HIV-RNA at the moment of vaccination. We report 4 cases of AHB in persons without immune response despite a correct vaccination. After HBV complete vaccination, most guidelines recommend serologic determination of antibodies. When anti-HBs concentration of 10IU/ml are not reached, revaccination may be considered. Even more, based on clinical trials,7 double vaccine dose and extended schedules (0-1-2 and 6 months) are recommended in most guidelines.8,9

In persons that do not achieve HBV immune response, HIV treatment including tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) or tenofovir disoproxil alafenamide (TAF) may be a protective option. Some studies have demonstrated that ART with HBV active drugs protects against the occurrence of de-novo HBV infection.10,11 Even more TDF has showed greater potency than lamivudine as HBV prophylactic effect.12 In our study, as the analyzed period includes years where ART was indicated dependent on CD4 count, most persons were not receiving ART at the moment of AHB, and, of the 3 persons on ART, only one was receiving lamivudine- which, notwithstanding, did not prevent the acute infection.

Reciprocal interactions between HIV and HBV lead to an increased risk for chronic evolution and severe complications.13 In our cohort we did not see any severe hepatitis. A recent Italian study found that more than on third of HIV infected persons with AHB developed a chronic HBV infection (CHB).14 In our short series the development of chronicity was lower (2/18, 11%), however this is still higher of what has been reported among HIV negative persons (5%).15 Morsica et al., found a marginal protective effect of ART on the progression of AHB to CHB.14 The two persons of our cohort that developed a CHB were not under ART at the time of the AHB.

The main limitation of our study relies in its retrospective design, and the low number of AHB that we observed. Thus, our conclusions should be taken cautiously. However, there is not much recent information about rates or evolution of AHB in HIV positive persons. Even more, there is little information about cases of AHB among persons without adequate immune response to vaccination.

In conclusion, the incidence of AHB in HIV-infected persons in our setting is decreasing in the last 5 years, although it is still higher than that of the general population. Efforts should be made to reach universal HBV vaccination among HIV-infected persons and TDF-based treatments should be considered in those without serologic response to vaccination.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.