Further studies are needed to evaluate the level of effectiveness and durability of HAART to reduce the risk of HIV sexual transmission in serodiscordant couples having unprotected sexual practices.

MethodsA cross-sectional study was conducted with prospective cohort of heterosexual HIV serodiscordant couples where the only risk factor for HIV transmission to the uninfected partner (sexual partner) was the sexual relationship with the infected partner (index case). HIV prevalence in sexual partners at enrolment and seroconversions in follow-up were compared by antiretroviral treatment in the index partner, HIV plasma viral load in index cases and sexual risk exposures in sexual partners. In each visit, an evaluation of the risks for HIV transmission, preventive counselling and screening for genitourinary infections in the sexual partner was performed, as well as the determination of the immunological and virological situation and antiretroviral treatment in the index case.

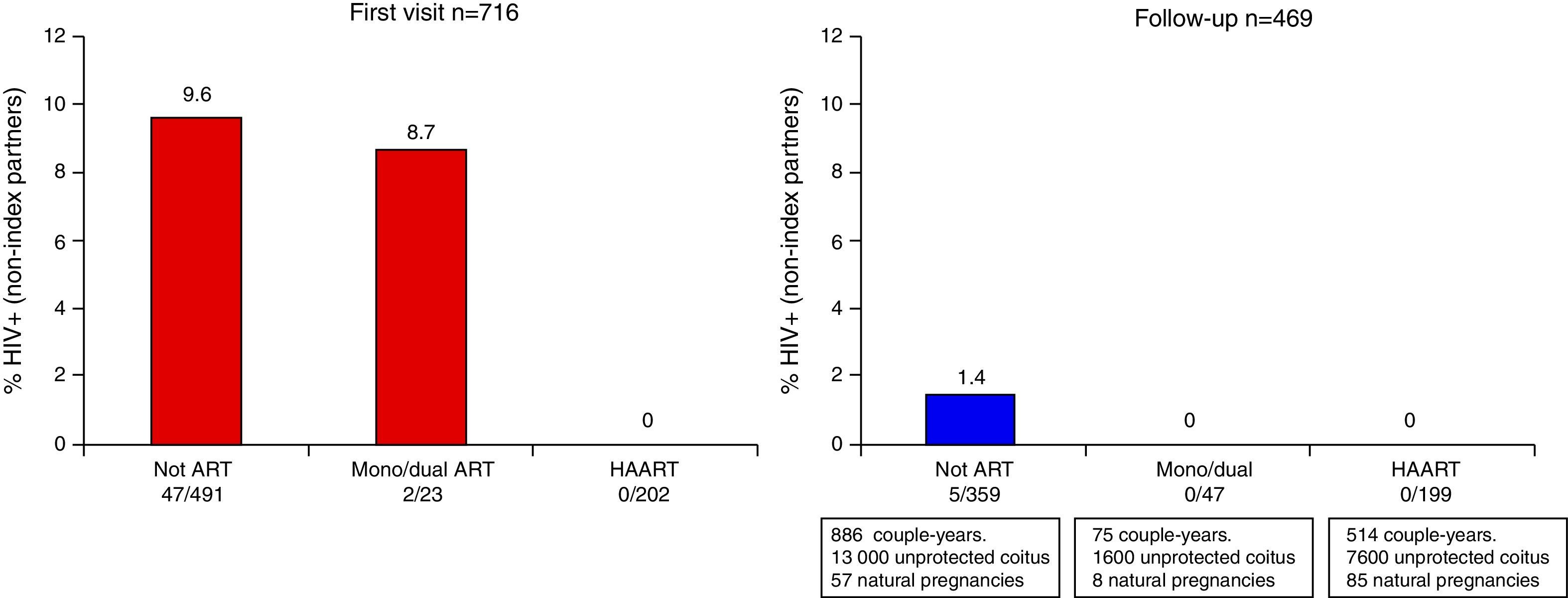

ResultsAt enrolment no HIV infection was detected in 202 couples where the index case was taking HAART. HIV prevalence in sexual partners was 9.6% in 491 couples where the index case was not taking antiretroviral treatment (p<0.001). During follow-up there was no HIV seroconversion among 199 partners whose index case was taking HAART, accruing 7600 risky sexual exposures and 85 natural pregnancies. Among 359 couples whose index case was not under antiretroviral treatment, over 13,000 risky sexual exposures and 5 HIV seroconversions of sexual partners were recorded. The percentage of seroconversion among couples having risky sexual intercourse was 2.5 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.1–5.6) when the index case did not undergo antiretroviral treatment and zero (95% CI: 0–3.2) when the index case received HAART.

ConclusionsThe risk of sexual transmission of HIV from individuals with HAART to their heterosexual partners can become extremely low.

Son necesarios más estudios que evalúen el nivel de efectividad del TARGA y su duración para prevenir la transmisión sexual del VIH en parejas serodiscordantes que tienen prácticas sexuales sin protección.

MétodosEstudio transversal y cohorte prospectiva de parejas heterosexuales serodiscordantes al VIH en las cuales el único factor de riesgo para la transmisión del VIH al sujeto no infectado (contacto) fue la relación sexual con el sujeto infectado (caso índice). Se estudió la prevalencia del VIH al inicio y las seroconversiones durante el seguimiento comparándolas en función de si el caso índice recibía tratamiento antirretroviral, la carga viral plasmática del VIH del caso índice y las exposiciones sexuales de riesgo del contacto. En cada visita se realizó una evaluación de riesgos para el VIH, consejo preventivo y despistaje de infecciones genitourinarias en el contacto, y se determinó la situación inmunológica, virológica y el tratamiento antirretroviral del caso índice.

ResultadosAl reclutamiento no se detectó ninguna infección en las 202 parejas cuyo caso índice recibía TARGA, mientras que entre las 491 con caso índice sin tratamiento, la prevalencia fue del 9,6% (p<0,001). Durante el seguimiento no hubo seroconversiones en 199 parejas con caso índice bajo TARGA, aunque tuvieron 7.600 exposiciones sexuales no protegidas y 85 gestaciones naturales. Entre las 359 parejas con caso índice sin tratamiento se registraron más de 13.000 exposiciones sexuales de riesgo y 5 seroconversiones. Cuando el caso índice no recibía tratamiento, el porcentaje de seroconversión en parejas con prácticas sexuales de riesgo fue 2,5% (IC 95%: 1,1–5,6) y cero cuando recibía TARGA (IC 95%: 0–3,2)

ConclusionesEl riesgo de transmisión sexual del VIH de personas tratadas con TARGA a sus parejas heterosexuales puede llegar a ser extremadamente bajo.

HIV plasma viral load is the major risk factor for heterosexual transmission of HIV.1–3 Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) can reduce HIV/RNA to undetectable levels in plasma4 and genital fluids.5 Data suggest that HIV-infected people with persistent undetectable viral load are much less infectious, and may be less likely to transmit HIV to their sexual partners.6,7 Results of recent studies indicate that HAART can have an important role in the prevention of heterosexual transmission of HIV.8,9 There are few prospective studies in HIV serodiscordant couples in developed countries.10

A cohort of heterosexual serodiscordant couples was launched in 1989 in Madrid and about one thousand couples had been enrolled up to 2010. In preliminary results published in 2005, 2009 and 2010,6,11,12 we described a very important reduction in the probability of sexual HIV transmission when the infected (index) partner was receiving HAART. These preliminary results were consistent with other relevant observational studies.7,13 Subsequently, a large randomized multicentre clinical trial indicated that early initiation of HAART drastically reduces the rates of heterosexual HIV transmission.14 These results seem to confirm the individual and public health preventive benefits of effective HAART. However, researchers agree that further research is needed to determine if the level and durability of protection conferred by HAART differs in the presence of other factors affecting sexual HIV transmission such as unprotected sexual practices and genitourinary infections.10,15

The aim of this study was to help elucidate some of these issues in light of the most recent data from the Madrid cohort of heterosexual HIV serodiscordant couples. Therefore, we analyzed the baseline prevalence of HIV infection in the sexual partners, HIV incidence throughout follow-up, and the probability of transmission according to whether the index case received antiretroviral treatment or not, HIV viral load in the index case and sexual risk exposures in the sexual partner.

MethodsSetting and study populationCouples participating in this study were included in a specific programme for heterosexual HIV serodiscordant couples launched in 1989 in a clinic for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in Madrid, Spain. Each new patient diagnosed with HIV infection was advised that his or her sexual partner should visit the clinic. The programme includes scheduled six-monthly check-ups. At each visit, the index case undergoes clinical follow-up, and is provided access to free antiretroviral treatment meeting current international and local guidelines in use during each period. The sexual partner is recommended to undergo an HIV test and screening for genitourinary infections. Couples are systematically advised against having unprotected sex, and they receive free condoms.

The protocol of this study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínico San Carlos in Madrid, Spain. The patients were informed about the aim of the study and they agreed to participate by signing an informed consent.

A cross-sectional analysis of HIV prevalence in sexual partners was carried out at recruitment, including all heterosexual couples between 1989 and 2010 who met the following criteria: on-going sexual relationship during at least the past six months, well known clinical and therapeutic status of the index case, and no known risk exposure other than the heterosexual relationship with the index case. After informed consent of both partners, stable heterosexual couples who were serodiscordant for HIV in the first visit and who returned for at least one follow-up visit were included in an observational prospective cohort analysis to quantify the risk of heterosexual HIV transmission according to sexual risk exposures in the sexual partner and antiretroviral therapy in the index case. Follow-up began on the date of the first negative HIV test result for the sexual partner, and the end point was a positive HIV test result. Data were censored at the last follow-up visit for participants who failed to return for check-ups for more than 24 months, whose relationship ended, or whose sexual partner reported any risk exposure outside the relationship. For the remaining couples, follow-up was censored at the last check-up before 31 December 2010.

Trained physicians used specific forms in each visit to collect information on epidemiological, clinical and sexual behaviour. They asked sexual partners the total number of sexual intercourses (vaginal and anal intercourses) during the previous six months (at recruitment) or since the previous visit (at follow-up). Respondents reported the number of unprotected sexual contacts (without condom) using a semi-quantitative scale (never, less than half of the times, more than half of the times or always); coefficients 0, 0.33, 0.67 and 1 were assigned, respectively, to this scale in order to estimate the frequency of “risky sexual practices”. Overall, unprotected sexual risk practices and condom breakage or slippage during intercourse were considered “risky sexual exposures”. Couples were categorized in each visit according to antiretroviral treatment received by the index case: not taking antiretroviral treatment, taking mono/dual therapy, and taking HAART.

Laboratory testsAt baseline and every visit thereafter serum antibodies to HIV-1/2 were determined in the sexual partners, and reactive samples were confirmed by western blotting. CD4 count in the index case was determined by flow cytometry and plasma HIV RNA by a branched DNA assay. The lower limit of detection was 500copies/mL until 1999, and 50copies/mL thereafter. Syphilis was routinely evaluated by reaginic (RPR) and treponemic (ELISA and TPPA or FTA-abs) tests. Others STIs were evaluated in men having signs/symptoms or whose partners had been diagnosed with an STI. Gynaecological examinations included STI screening in cervical and vaginal exudates.

Statistical analysisHIV prevalence at enrolment in sexual partners was observed and a stratified analysis by selected characteristics of the couples was performed to rule out the main potential confounding factors in the association between HIV prevalence in sexual partners and treatment in index cases. In the follow-up analysis, we quantified some characteristics of the couples, events occurring during follow-up and the number of new HIV seroconversions. Moreover, we estimated the incidence rate of seroconversion by couple-years of follow-up and the probability of transmission per sexual risk exposure between two successive visits among those receiving HAART, mono/dual therapy with nucleoside analogue reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) or without treatment. Index cases who started or changed antiretroviral treatment between two successive visits were classified in the less effective treatment category. Genitourinary infections and other circumstances detected at a visit were considered as covariates present during the whole time period since the previous visit. Continuous variables were compared with the Wilcoxon test, proportions with the Fisher's exact test and rates with exact methods. Interquartile ranges (IQR) for medians, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for rates (assuming a Poisson distribution) and risks (assuming a binomial distribution) were calculated.

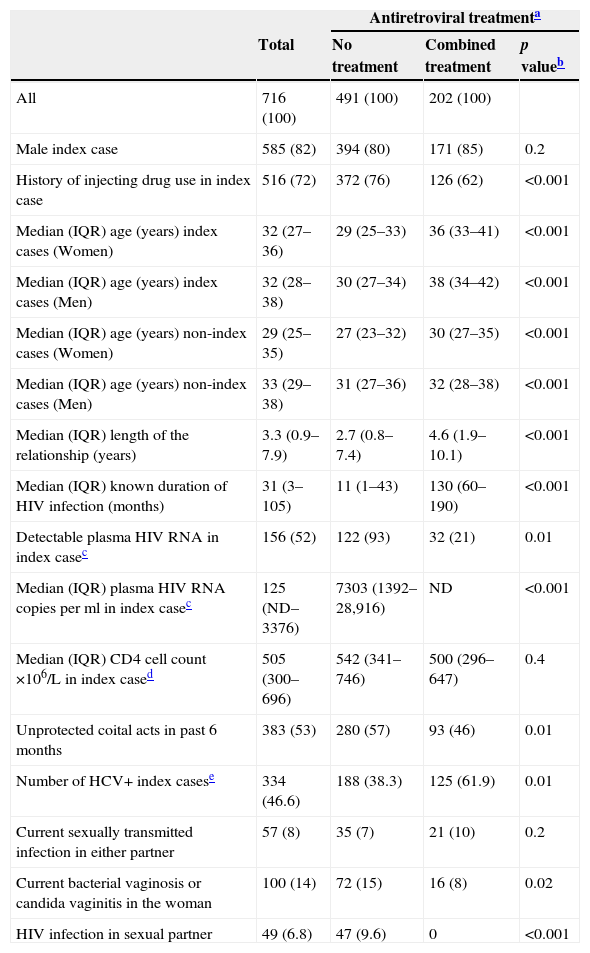

ResultsHIV prevalence at enrolmentBetween 1989 and 2010, 716 heterosexual couples, in which only one partner had previously received a diagnosis of HIV infection, were recruited for this study. Characteristics of these couples according to treatment of the index case (no treatment or HAART) are showed in Table 1. In 585 (82%) couples the index case was a man and in 516 (72%) the index case had a history of injecting drug use (IDU). The median length of the relationship was 3.3 years. In 491 (69%) couples the index case was not taking any antiretroviral treatment: in 333 because antiretroviral drugs were not yet available, in 135 who did not meet the criteria for treatment and in 23 who declined treatment. Among the index cases receiving antiretroviral therapy, 23 were under mono/dual therapy receiving only NRTIs and 202 were receiving HAART. HIV viral load was detectable in 93% (122/131 with viral load data) of the index cases who were not taking antiretroviral treatment compared to 21% (32/152 with viral load data) of those undergoing HAART (p=0.01). The median of VL in these last couples was 1238 (IQR=687–21,599). The proportion of couples having unprotected sexual intercourses was lower among those whose index case was taking HAART (93/202 (46%) vs 280/491 (57%), p=0.01). Among the 32 couples with index cases under HAART and detectable VL, only six reported unprotected sexual practices. Index cases of these couples were less than one year under HAART. Overall, 334 (46.6%) index cases were HCV+, most of them (90.7%) ex-IDU. They represented 38.3% of the untreated index cases and 61.9% of those under HAART (p<0.001). Although there was no significant difference in the proportion of current STIs in either partners according to antiretroviral treatment of the index case, the prevalence of bacterial vaginosis/candida vaginitis was significantly higher among women in couples in which the index case was not being treated (72/491 (15%) vs 16/202 (8%), p=0.02).

Characteristics of couples enrolled during 1989–2010 according to treatment of index case.

| Antiretroviral treatmenta | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | No treatment | Combined treatment | p valueb | |

| All | 716 (100) | 491 (100) | 202 (100) | |

| Male index case | 585 (82) | 394 (80) | 171 (85) | 0.2 |

| History of injecting drug use in index case | 516 (72) | 372 (76) | 126 (62) | <0.001 |

| Median (IQR) age (years) index cases (Women) | 32 (27–36) | 29 (25–33) | 36 (33–41) | <0.001 |

| Median (IQR) age (years) index cases (Men) | 32 (28–38) | 30 (27–34) | 38 (34–42) | <0.001 |

| Median (IQR) age (years) non-index cases (Women) | 29 (25–35) | 27 (23–32) | 30 (27–35) | <0.001 |

| Median (IQR) age (years) non-index cases (Men) | 33 (29–38) | 31 (27–36) | 32 (28–38) | <0.001 |

| Median (IQR) length of the relationship (years) | 3.3 (0.9–7.9) | 2.7 (0.8–7.4) | 4.6 (1.9–10.1) | <0.001 |

| Median (IQR) known duration of HIV infection (months) | 31 (3–105) | 11 (1–43) | 130 (60–190) | <0.001 |

| Detectable plasma HIV RNA in index casec | 156 (52) | 122 (93) | 32 (21) | 0.01 |

| Median (IQR) plasma HIV RNA copies per ml in index casec | 125 (ND–3376) | 7303 (1392–28,916) | ND | <0.001 |

| Median (IQR) CD4 cell count ×106/L in index cased | 505 (300–696) | 542 (341–746) | 500 (296–647) | 0.4 |

| Unprotected coital acts in past 6 months | 383 (53) | 280 (57) | 93 (46) | 0.01 |

| Number of HCV+ index casese | 334 (46.6) | 188 (38.3) | 125 (61.9) | 0.01 |

| Current sexually transmitted infection in either partner | 57 (8) | 35 (7) | 21 (10) | 0.2 |

| Current bacterial vaginosis or candida vaginitis in the woman | 100 (14) | 72 (15) | 16 (8) | 0.02 |

| HIV infection in sexual partner | 49 (6.8) | 47 (9.6) | 0 | <0.001 |

Figures are numbers (percentages) of participants unless stated otherwise.

IQR=interquartile range; ND=non-detectable plasma HIV RNA.

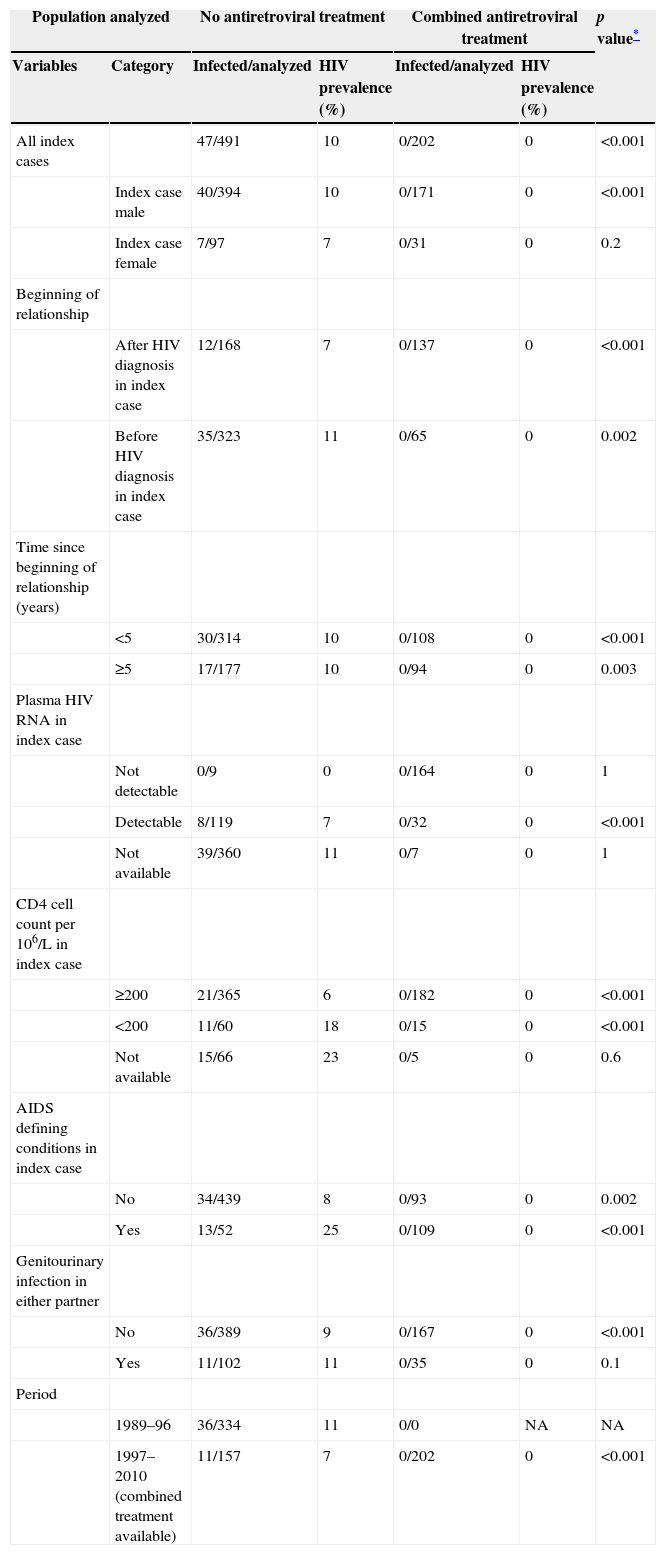

HIV prevalence in sexual partners was 6.8% (49/716) overall: 11% (38/352) among those diagnosed in 1989–1996 and 3% (11/364) in persons diagnosed in 1997–2010, when HAART was available (p<0.001). The prevalence of HIV infection was 9.6% (47/491) in couples where the index cases were not taking antiretroviral treatment and 8.7% (2/23) among partners of index cases taking mono/dual therapy, but no HIV infection was detected in partners of index cases taking HAART (0/202; p<0.001) (Fig. 1). The stratified analyses by selected characteristics of the couples shown in Table 2 excluded the main potential confounding factors for this last association.

Prevalence of HIV infection at first visit among sexual partners, according to selected characteristics of the couples.

| Population analyzed | No antiretroviral treatment | Combined antiretroviral treatment | p value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Category | Infected/analyzed | HIV prevalence (%) | Infected/analyzed | HIV prevalence (%) | |

| All index cases | 47/491 | 10 | 0/202 | 0 | <0.001 | |

| Index case male | 40/394 | 10 | 0/171 | 0 | <0.001 | |

| Index case female | 7/97 | 7 | 0/31 | 0 | 0.2 | |

| Beginning of relationship | ||||||

| After HIV diagnosis in index case | 12/168 | 7 | 0/137 | 0 | <0.001 | |

| Before HIV diagnosis in index case | 35/323 | 11 | 0/65 | 0 | 0.002 | |

| Time since beginning of relationship (years) | ||||||

| <5 | 30/314 | 10 | 0/108 | 0 | <0.001 | |

| ≥5 | 17/177 | 10 | 0/94 | 0 | 0.003 | |

| Plasma HIV RNA in index case | ||||||

| Not detectable | 0/9 | 0 | 0/164 | 0 | 1 | |

| Detectable | 8/119 | 7 | 0/32 | 0 | <0.001 | |

| Not available | 39/360 | 11 | 0/7 | 0 | 1 | |

| CD4 cell count per 106/L in index case | ||||||

| ≥200 | 21/365 | 6 | 0/182 | 0 | <0.001 | |

| <200 | 11/60 | 18 | 0/15 | 0 | <0.001 | |

| Not available | 15/66 | 23 | 0/5 | 0 | 0.6 | |

| AIDS defining conditions in index case | ||||||

| No | 34/439 | 8 | 0/93 | 0 | 0.002 | |

| Yes | 13/52 | 25 | 0/109 | 0 | <0.001 | |

| Genitourinary infection in either partner | ||||||

| No | 36/389 | 9 | 0/167 | 0 | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 11/102 | 11 | 0/35 | 0 | 0.1 | |

| Period | ||||||

| 1989–96 | 36/334 | 11 | 0/0 | NA | NA | |

| 1997–2010 (combined treatment available) | 11/157 | 7 | 0/202 | 0 | <0.001 | |

Figures are numbers and percentages.

NA=not available.

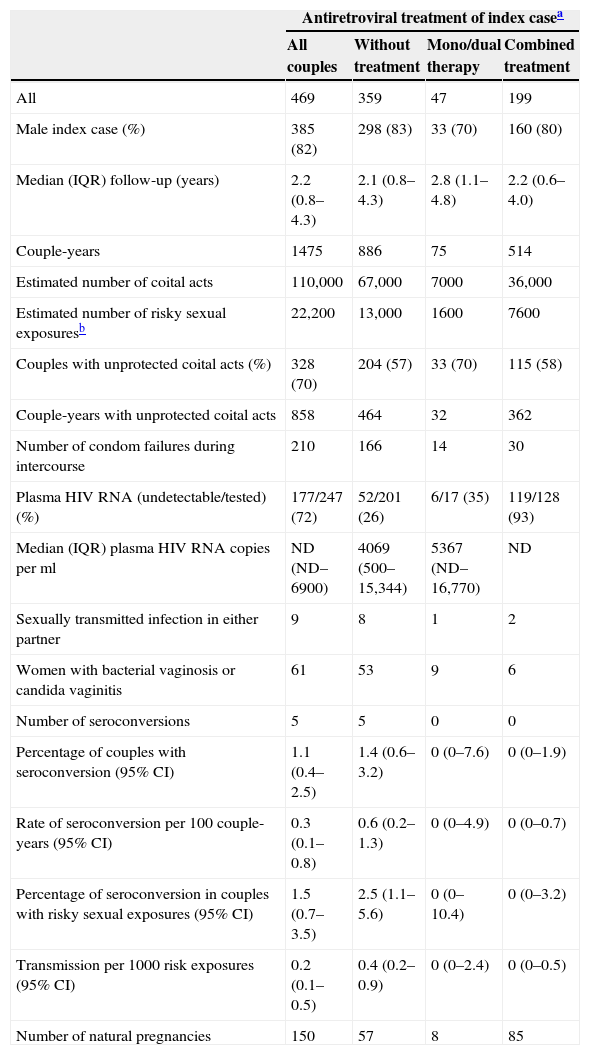

HIV transmission was evaluated in 469 couples who were serodiscordant at recruitment and who had at least one follow-up visit. About 20% of couples met criteria for censored follow-up: five HIV seroconversions, 23 deaths of a partner, 46 ended relationships and 18 sexual partners who had sexual contacts with another person. About 57% of the couples in follow-up did not return for a check-up in 24 months, whereas 24% were still in follow-up in December 2010. Characteristics of couples and events occurring during follow-up according to antiretroviral treatment are shown in Table 3. Median follow-up time was 2.2 years (IQR: 0.8–4.3), and 42% of couples were followed between two and 21 years. Median follow-up for couples with the index case under HAART was also 2.2 years (IQR: 0.6–4.0). A total of 1475 couple-years of follow-up were accrued. About 110,000 coital acts were estimated (6.2 per month), of which 22,200 were risky sexual exposures (1.3 per month). During one or more follow-up periods, 70% of couples reported unprotected sexual contacts, and 210 condom failures were reported among couples who always used condoms. There were about 13,000 sexual risk exposures (166 condom failures) in 886 couple-years when the index case was not taking antiretroviral treatment, and the median HIV plasma viral load was 4069copies/mL (IQR: 500–15,344). Bacterial vaginosis/candida vaginitis was detected in 15% of women in these couples.

Characteristics of the couples and events occurring during follow-up according to antiretroviral treatment of index case.

| Antiretroviral treatment of index casea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All couples | Without treatment | Mono/dual therapy | Combined treatment | |

| All | 469 | 359 | 47 | 199 |

| Male index case (%) | 385 (82) | 298 (83) | 33 (70) | 160 (80) |

| Median (IQR) follow-up (years) | 2.2 (0.8–4.3) | 2.1 (0.8–4.3) | 2.8 (1.1–4.8) | 2.2 (0.6–4.0) |

| Couple-years | 1475 | 886 | 75 | 514 |

| Estimated number of coital acts | 110,000 | 67,000 | 7000 | 36,000 |

| Estimated number of risky sexual exposuresb | 22,200 | 13,000 | 1600 | 7600 |

| Couples with unprotected coital acts (%) | 328 (70) | 204 (57) | 33 (70) | 115 (58) |

| Couple-years with unprotected coital acts | 858 | 464 | 32 | 362 |

| Number of condom failures during intercourse | 210 | 166 | 14 | 30 |

| Plasma HIV RNA (undetectable/tested) (%) | 177/247 (72) | 52/201 (26) | 6/17 (35) | 119/128 (93) |

| Median (IQR) plasma HIV RNA copies per ml | ND (ND–6900) | 4069 (500–15,344) | 5367 (ND–16,770) | ND |

| Sexually transmitted infection in either partner | 9 | 8 | 1 | 2 |

| Women with bacterial vaginosis or candida vaginitis | 61 | 53 | 9 | 6 |

| Number of seroconversions | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Percentage of couples with seroconversion (95% CI) | 1.1 (0.4–2.5) | 1.4 (0.6–3.2) | 0 (0–7.6) | 0 (0–1.9) |

| Rate of seroconversion per 100 couple-years (95% CI) | 0.3 (0.1–0.8) | 0.6 (0.2–1.3) | 0 (0–4.9) | 0 (0–0.7) |

| Percentage of seroconversion in couples with risky sexual exposures (95% CI) | 1.5 (0.7–3.5) | 2.5 (1.1–5.6) | 0 (0–10.4) | 0 (0–3.2) |

| Transmission per 1000 risk exposures (95% CI) | 0.2 (0.1–0.5) | 0.4 (0.2–0.9) | 0 (0–2.4) | 0 (0–0.5) |

| Number of natural pregnancies | 150 | 57 | 8 | 85 |

IQR=interquartile range; ND=not detectable; CI=confidence interval.

The index case was taking HAART in 199 couples during 514 couple-years, accruing over 7600 sexual risk exposures (30 condom failures), and 93% (119/128) of index cases had undetectable plasma HIV RNA. Bacterial vaginosis/candida vaginitis was diagnosed in 3% of women in these couples. There were five HIV seroconversions of sexual partners among 359 couples whose index case was not taking HAART, and no seroconversion among those whose index case was taking it. The ratio of HIV transmission per 1000 risk exposures was 0.4 for the couples with index cases without antiretroviral treatment and zero for those receiving HAART. The percentage of seroconversion among couples having risky sexual exposures was 2.5 (95% CI: 1.1–5.6) when the index case was not under antiretroviral treatment and zero (95% CI: 0–3.2) when he or she received HAART (Table 3). There was, however, no significant difference between the probability of transmission of index partner with and without HAART (p=0.17).

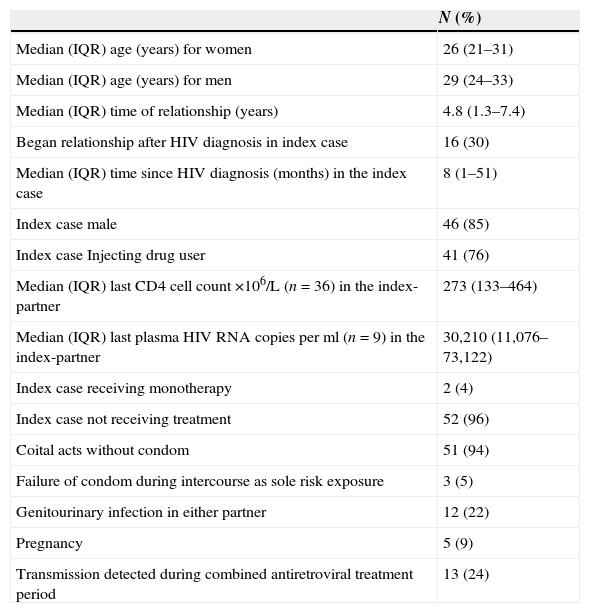

Characteristics of couples in which HIV transmission occurredOverall, HIV transmission was detected in 54 couples; 49 of these transmissions were identified at enrolment and five during follow-up (Table 4). Two of the 54 index cases were being treated with one antiretroviral drug, but none was receiving HAART. Three couples (two at enrolment and one at follow-up) had not reported any unprotected intercourse, and transmission was associated with condom failure. None of them received antiretroviral post-exposure prophylaxis. In 12 couples (22%) one or both partners had genitourinary infections: in index cases the most frequent were urethritis, syphilis, genital warts, vaginitis and genital herpes; in sexual partners cervicitis, it was genital warts and genital herpes. Plasma HIV RNA was measured in nine transmitter partners and all of them had a detectable concentration, ranging from 362 to 257,325copies/mL. Three of the five transmissions during follow-up occurred before the availability of VL. In the other two transmissions the index cases had a viral load of 35,410 and 73,122copies/mL, respectively.

Characteristics of 54 couples with diagnosis of HIV infection in the sexual partner.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Median (IQR) age (years) for women | 26 (21–31) |

| Median (IQR) age (years) for men | 29 (24–33) |

| Median (IQR) time of relationship (years) | 4.8 (1.3–7.4) |

| Began relationship after HIV diagnosis in index case | 16 (30) |

| Median (IQR) time since HIV diagnosis (months) in the index case | 8 (1–51) |

| Index case male | 46 (85) |

| Index case Injecting drug user | 41 (76) |

| Median (IQR) last CD4 cell count ×106/L (n=36) in the index-partner | 273 (133–464) |

| Median (IQR) last plasma HIV RNA copies per ml (n=9) in the index-partner | 30,210 (11,076–73,122) |

| Index case receiving monotherapy | 2 (4) |

| Index case not receiving treatment | 52 (96) |

| Coital acts without condom | 51 (94) |

| Failure of condom during intercourse as sole risk exposure | 3 (5) |

| Genitourinary infection in either partner | 12 (22) |

| Pregnancy | 5 (9) |

| Transmission detected during combined antiretroviral treatment period | 13 (24) |

Figures are numbers (percentages) of participants or median (interquartile range).

IQR=interquartile range.

Our study revealed that no index case receiving HAART transmitted the HIV infection to his or her heterosexual partner. No cases of transmission were found either among the 202 couples analyzed at the first visit in which the index case was taking HAART, or among the 199 that were followed during 514 couple-years. This allows us to establish, with less than 5% error, that the probability of HIV transmission among couples where the index case was under HAART is lower than 1 in 2000 risk exposures, and the rate of seroconversion is less than 1 in 100 couple-years. Conversely, among couples whose index case was not taking HAART, we detected 49 HIV infections at the first visit and five during follow-up. This represents 2.5 HIV transmissions per 100 couples having risky sexual exposures whose index case was not receiving treatment. The Madrid cohort of heterosexual HIV serodiscordant couples is one of the most representative cohorts of this type in developed countries. Our previous study12 is the only one to report sexual HIV-1 transmission stratified by antiretroviral treatment use in a high income country.10 A prominent feature of the present study is the considerably long follow-up, a median of 2.2 years (IQR: 0.8–4.3), higher than that reported in other relevant studies.13,14 About 42% of our couples were followed up between two and 21 years, and around 25% of those where the index case was under HAART were followed for four or more years.

In our study, sexual behaviour data are collected in a detailed and exhaustive way. This allowed us to estimate a very large number of risky sexual exposures (22,200) occurring in 70% of couples during one or more follow-up. This high proportion of couples having unprotected sex differs from the results reported in other studies.13–15 Recently, preliminary results of the Partner Study presented in the CROI 2014 conference showed similar results to ours, with an estimated total number of condomless vaginal sex acts of 28,000 in 485 heterosexual couples with VL <200copies/mL.16 A partial explanation for this difference could be that participants in cohort studies probably exhibit greater behavioural similarities to serodiscordant couples in the general population than to those enrolled in clinical trials. Moreover, longer follow-up periods could result in increased instances of unsafe sex. In addition, in 2002 a counselling programme for HIV serodiscordant couples with reproductive desire by natural means was launched in our clinic, and in our study 18% of couples carried out at least one reproductive attempt during the follow-up period, resulting in 150 pregnancies, 85 of them in couples whose index case was under HAART. Studies in heterosexual HIV serodiscordant couples with viral suppression have reported, in all, a follow-up of 330 couple-years when condoms were not being used.15 Our results, reporting 362 couple-years not using condoms, attempt to help meet the need for studies with longer follow-up.

One hundred and forty-one couples reported systematic use of condoms and one accident (breakage or slippage) as the only risk exposure. In three of these couples, two at recruitment and one at follow-up, the index cases were not receiving antiretroviral treatment and condom failure resulted in the transmission of HIV to their sexual partners. In contrast, zero transmissions were found in couples having risky sexual exposures when the index case was taking HAART. Several meta-analyses of observational and cohort studies have found that 100% condom use reduces HIV transmission in heterosexual couples by about 80%.17 The HPTN 052 study has reported a 96% reduction when the HIV-positive partner was taking HAART.14 The studies conducted to date on heterosexual serodiscordant couples indicate that the small number of documented HIV transmissions occurred from individuals who had recently started therapy and in whom it is unlikely that undetectable viral load was achieved.13,14,18 Our previous study,12 together with two others,8,19 have been identified20 as the only ones in which full viral suppression was confirmed in the index cases under HAART. Pooled transmission rate for these studies was zero per 100 person-years (95% CI: 0–0.05).

Couples in our study maintained a closed and stable relationship for a median of 3.3 years, which justifies the relatively low proportion of STIs at recruitment (8%). While no changes were reported in other studies,14 STI incidence decreased considerably during follow-up (2%), probably as a result of our testing and counselling programme.11 STIs and other genitourinary infections can increase the probability of HIV transmission.1,21–25 Indeed, among couples in which STIs or genitourinary infections were diagnosed in one or both members, 12 HIV transmissions occurred when the index case was not treated. However, there was no HIV transmission when the index case was taking HAART. A high prevalence of HCV+ was identified at enrolment in the index cases, something related to the presence in our cohort of people with a history of IDU.

Our study has several limitations. HIV plasma viral load was only quantified in 9 of 54 couples in which a new HIV infection was detected, because most of them were diagnosed before 1996 when viral load testing was not yet available. Data were insufficient to respond clearly to the question about the actual risk of HIV transmission in the presence of STIs when HIV viral load is fully suppressed by HAART. In HIV seroconcordant couples, we could not assess whether viruses in both partners were genetically linked because in most of the cases phylogenetic analysis was not available. The index cases without HAART, in general, had no indication for treatment and had a relatively low VL; therefore, they are not representative of all HIV infected population without HAART.

In conclusion, our results suggest that HAART is highly effective to prevent the sexual HIV transmission in heterosexual serodiscordant couples where the infected partners have sustained plasma viral load suppression even when they practise unprotected sex. Thus, although consistent condom use has a considerable protective effect in the population, the preventive impact of HAART may be higher. In agreement with the latest WHO recommendations for treatment and prevention in serodiscordant couples,26 among other aspects such as the personalized preventive counselling, antiretroviral therapy should be offered to the HIV positive partner, regardless of his or her immune status, to reduce the likelihood of sexual HIV transmission.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interests.

FundingThis work was funded by the I Fellowship Programme, Gilead Spain and the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (grant CSO2011-26245).