Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) is a ubiquitous pathogen, whose primary infection is often asymptomatic and manifests as exanthema subitum in only 20% of cases.1

HHV-6 has the capacity to integrate into the human genome (ciHHV-6). However, the mechanisms involved in HHV-6 integration are still largely unknown.2–4 HHV-6 Integration into the gametes results in Mendelian transmission to offspring, with 1% of the worldwide human population carrying ci-HHV-6.5

It is well established that congenital HHV-6 infection results from the germline passage of ci-HHV-6 and the transplacental passage of maternal HHV-6 infection by either maternal primary infection or maternal virus reactivation.6 The severity of HHV-6 congenital disease largely depends on the intensity and duration of viral replication, and is related to the maternal anti-HHV6 immune response and the implementation of antiviral treatment. HHV-6 congenital infections are usually asymptomatic6,7 most likely due to the immune protection provided by maternal immunity. Nevertheless, the impact of the absence of maternal HHV-6-specific immune response in the setting of ci-HHV6 on the development of congenital HHV-6 infections is unknown.8

We describe the case of a 35-year-old pregnant woman without a relevant clinical history. Fetal screening sonography at week 12 of the pregnancy showed an isolated severe fetal pleural effusion. Amniocentesis was subsequently performed with a negative result for trisomy 13, 18 and 21. Nevertheless, real-time PCR in amniotic fluid was positive for HHV-6A and negative for other infections (varicella zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, Epstein–Barr virus, toxoplasmosis, herpesvirus 1 and 2 and Parvovirus B19). The patient presented a self-limited abdominal rash at weeks 8 of pregnancy as the only clinical symptom. Given the presence of massive fetal pleural effusion, the patient terminated the pregnancy at 22 weeks. The fetal autopsy showed a prominent pleural effusion, although no other macroscopic alterations were identified. Since HHV-6A had been previously detected in the amniotic fluid, the presence of HHV-6 real-time PCR was investigated in fetal tissues. Hence, all fetal tissues evaluated, including brain and lung tissues, showed the presence of HHV-6A. Four months after the abortion, the patient was referred to the infectious diseases unit of the hospital. HHV-6 viral loads were monitored in the patient by quantitative PCR in plasma (5.083copies/ml) and whole blood (4.896.701copies/ml) samples. A HHV-6 antiviral treatment with 900mg of oral valganciclovir every 12h was initiated. After four weeks, the HHV-6 PCR remained positive (6.940copies/ml). Consequently, genotypic antiviral resistance testing for HHV-6 was performed in plasma samples. This study did not reveal mutations associated with ganciclovir resistance.

We studied the HHV-6 serostatus in all family members (including her parents and three of her father's cousins who did not present any complications during the pregnancies). All members were found to be HHV-6-seropositive. In addition, we performed a ci-HHV-6 study from hair follicles. The study revealed that the patient (and the patient's father) were ciHHV-6A, while the patient's mother had undetectable HHV-6 DNA levels. In addition, the ci-HHV-6 analysis showed that only one cousin, named cousin 2, was also ciHHV-6A. Both, the patient's father and cousin 2 had HHV-6 positive viral load in plasma (260copies/ml and 395copies/ml respectively).

Since fetal tissues were positive for HHV-6 by real-time PCR in a mother with ci-HHV-6, we tested for the presence of ci-HHV-6 in the fetus by FISH. As expected, HHV-6 signals were observed in most (95%) of the evaluated cells in both brain and lung fetal tissues.

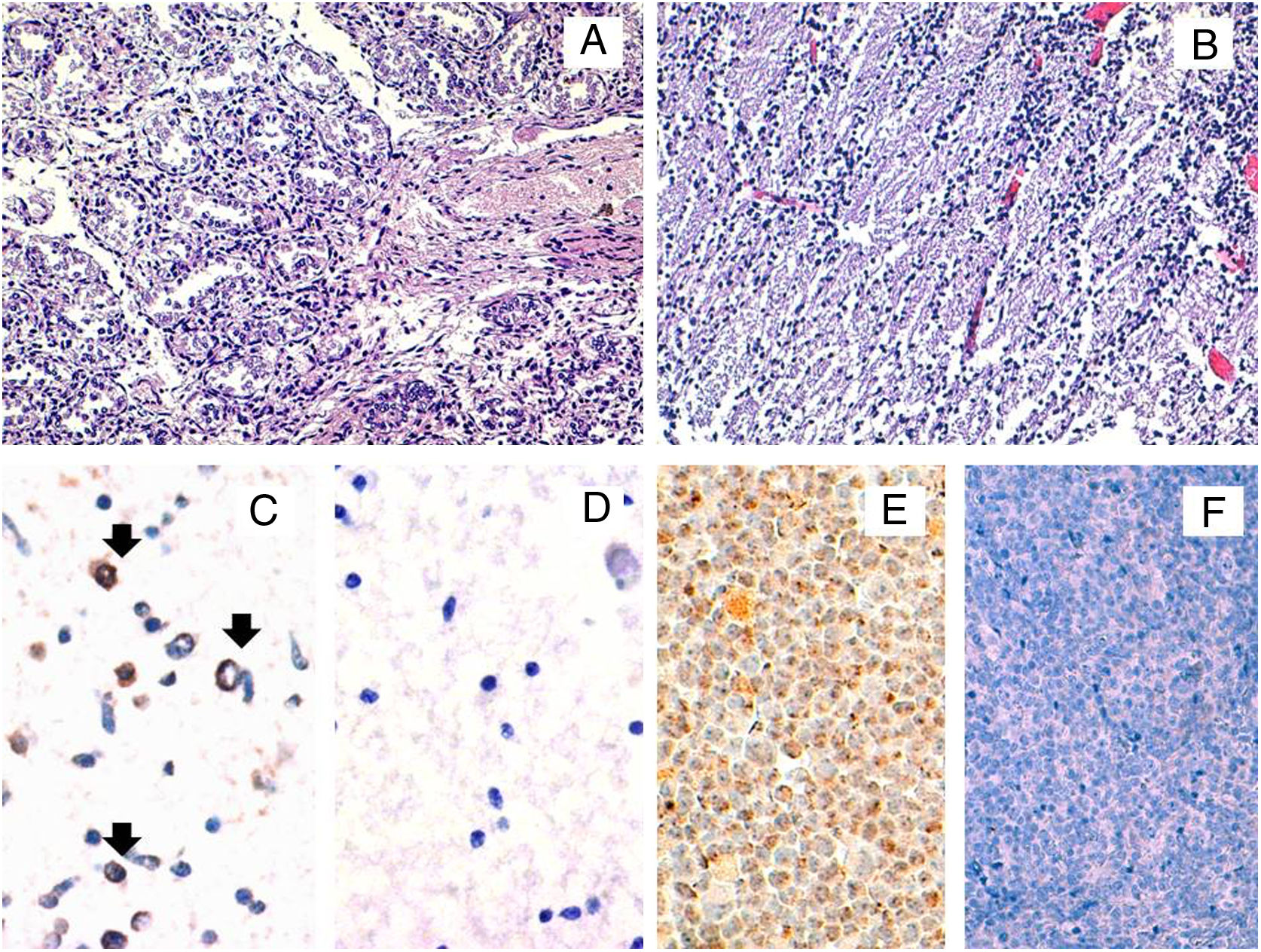

In order to confirm the expression of viral proteins, immunohistochemical staining for the late antigen gp116/64/54 was performed. Positivity was observed in the brain, thus suggesting an active infection but not in the lung (Fig. 1). All female family members showed HHV-6-specific response for at least one cytokine in at least either CD4+ or CD8+ cells, except the patient. When we compared the cytokine production between both ciHHV-6A female family members, we observed that cousin 2 produced IFN-γ and TNF-α, while the patient did not show any cytokine production.

Histopathological and HHV-6A immunohistochemical studies in fetal tissues. The microscopic study by conventional hematoxylin and eosin stainings of the fetal lung (A) and brain (B) tissues did not reveal any histopathological finding. The immunohistochemical study for the HHV-6 late antigen gp116/64/54 showed positive cells in the brain (black arrows) (C). Representative image of HHV-6 negative brain control tissue incubated with protease negative control reagent (D) HSB2 cells infected with HHV-6A were used as a positive control (E). HHV-6 negative tonsil tissue was used as a negative control (F). Original magnifications: A and B: 200×; C, D and E: 400×.

We studied if the patient's lack of response to HHV-6 antigens also occurred against another viral antigen such as CMVpp65, which is a highly immunodominant protein for T-cell responses. We observed that her CMV-specific response was restricted to the production of TNF-α.

In conclusion, we present a case of HHV-6 congenital infection in the setting of ci-HHV-6 with an absence of maternal HHV-6-specific T-cell response, which suggests the possible role of maternal HHV-6 immunity on the development of congenital infection. Further studies are necessary to confirm our observations.

FundingThis work was supported by Plan Nacional I+D+I 2013-2016 and Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Subdirección General de Redes y Centros de Investigación Cooperativa, Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases (REIPI RD12/0015 and RD16/0016) co-financed by European Development Regional Fund ERDF “A way to achieve Europe”, Operative program Intelligent Growth 2014–2020.

Other researchers participating in the study: Julián Torre-Cisneros, Manuel Causse (Hospital Reina Sofia, Córdoba), Anna Cervilla, Marta Marginet, Antonio Martinez (Clinic Hospital, Barcelona).

Conflict of interestsAll authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

We are grateful to the patient and all family members.