In Mexico, cancer is the second leading cause of death after cardiovascular diseases, and colorectal cancer (CRC) represents 4% of all deaths due to cancer. More than 80% of patients with CRC are treated in tertiary cancer centers with advanced tumors (stages III and IV). However, there is no colonoscopy-based screening program. Our primary objective was to determine the prevalence of colorectal neoplasm.

Materials and methodsA prospective, cross-sectional study was conducted, by using a consecutive series of subjects who underwent their first colonoscopy screening. Patients between 40 and 79 years of age and in good general health and in whom colorectal cancer was not suspected were included.

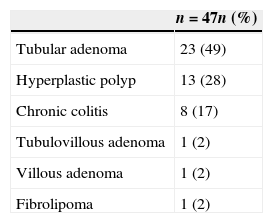

ResultsA total of 600 personal letters were sent. Of these, 123 subjects responded to the invitation, of which 14 were excluded. A total of 99 patients completed the study, 73 (74%) were women and 26 (26%) were men, with a mean (±SD) age of 50.1±7.41, with a mean BMI of 27.20±3.74kg/m2. Overall, 35 (35%) patients had 47 colorectal neoplasm. Among these, there were 25 adenoma (9 were advanced adenoma) in 17 (17%) patients. The location of the lesions was: caecum 6.3%, ascending colon 8.5%, transverse 19.1%, descending 19.1%, sigmoid 21.2%, and rectum 25.5%. There was a trend to have more adenoma in men (RR=2, 95%CI: 0.83–4.62, p=.139). In conclusion, the prevalence of adenomas detected by screening colonoscopy screening in the Mexican population is not different from that published in world literature.

En México el cáncer representa la segunda causa de muerte después de las enfermedades cardiovasculares, y el cáncer colorrectal (CCR) representa el 4% de todas las muertes debidas a cáncer. Más del 80% de los pacientes con cáncer colorrectal son detectados y tratados en estadios tardíos. Actualmente no existe un programa de tamizaje para cáncer colorrectal en nuestro país. Nuestro objetivo fue determinar la prevalencia de las neoplasias colorrectales en una muestra de pacientes mexicanos.

Material y métodosSe realizó un estudio prospectivo y transversal con pacientes consecutivos asintomáticos quienes se sometieron a su primera colonoscopia de tamizaje. Se incluyeron pacientes entre 40 y 79 años de edad sin ningún datos clínico que indicara la presencia de neoplasia colorrectal.

ResultadosFueron invitados a participar un total de 600 sujetos por medio de cartas personalizadas y 123 pacientes respondieron a la invitación. Catorce pacientes fueron excluidos. Un total de 99 pacientes completaron el estudio: 73 (74%) fueron mujeres; la media de edad fue 50.1±7.41 años, con un IMC de 27.20±3.74kg/m2. En total 35 (35%) pacientes tuvieron 47 neoplasias colorrectales. De estas lesiones, 25 fueron adenomas (9 fueron adenomas avanzados) y se detectaron en 17 pacientes. La localización de las lesiones fueron en ciego el 6.3%, en colon ascendente el 8.5%, en colon transverso el 19.1%, en colon descendente el 19.1%, en colon sigmoides el 21.2% y en recto el 25.5%. Se observó una tendencia a la presencia de mayor número de adenomas en los hombres (RR=2, IC95%: .83–4.62, p=.139). En conclusión, la prevalencia de adenomas detectados durante una colonoscopia de tamizaje en una muestra de población mexicana no es distinta a la publicada en la literatura mundial.

In 2014, the American Cancer Society (ACS) estimates that 136,830 new cases of colorectal cancer (CRC) will be diagnosed in women and men, and 50,130 individuals will die from this disease.1 CRC incidence and mortality rates have been declining for the past two decades, largely attributable to the contribution of screening to prevention and early detection. First guidelines for screening and surveillance for the early detection of adenomatous polyps and CRC in average-risk adults were published in 19802 and were updated in 2008 in an evidence-based consensus process that included the ACS, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer (USMSTF) and the American College of Radiology (ACR).3

Screening options may be chosen based on individual risk, personal preference and access. Average-risk adults should begin CRC screening at age 50 years with one of the following options: (1) annual high-sensitivity fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) or fecal immunochemical test (FIT); (2) flexible sigmoidoscopy (FSIG) every 5 years; (3) colonoscopy every 10 years; (4) double-contrast barium enema every 5 years, or (5) CT colonography every 5 years.

Data suggest that the incidence in younger patients is increasing.4 Most of these patients have no risk factors that were recognized before the diagnosis. In some studies, such younger persons present with more advanced disease and have a less favorable prognosis than older persons with newly diagnosed cancer. The yield from screening of persons in younger age groups has been investigated.5–7 However, not enough information exists regarding colorectal neoplasm in asymptomatic, average-risk persons 40–49 years of age.

In Mexico, cancer is the second leading cause of death after cardiovascular diseases. CRC represents 4% of all deaths due to cancer, with a specific mortality of 2.4 per 100,000 persons. According to cancer registry data updated in 2002, CRC represents 3.8% of new cancer cases.8

An increased in the frequency of CRC in the last 25 years has been demonstrated.9 The percentage of CRC in late stages is high. More than 80% of patients are treated in tertiary cancer centers with advanced tumors (stages III and IV).10 Late diagnosis of the CRC may be attributed to the complete absence of screening programs and contributes to the low survival of these patients.

Although the reported mortality in Mexico is less than 5/100,000 habitants,11 the lowest worldwide, there is clear disagreement between tumor stage at diagnosis, scarcity of resources and reported mortality particularly due to the poor state of cancer data collection. The fragmentation of the institutional arrangements contributes to poor quality of statistical data available in Mexico. The incidence and mortality of CRC and premalignant lesions in 2014 are unknown.12

There is an urgency for a national CRC screening program; however, socio-cultural and economic factors have negatively influenced the initiative.

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of data from a colonoscopy-based screening program for colorectal cancer in Mexico. Our primary objective was to determine the prevalence of colorectal neoplasm.

Materials and methodsA cross-sectional study was conducted by using a consecutive series of subjects who underwent their first colonoscopy screening as part of an employee-provided wellness program at the Medica Sur Hospital in Mexico City, between 2009 and 2010. Potential study subjects were approached by an invitation letter explaining the nature of the study; also, public announcements were posted to the Hospital web site. They were eligible if they were 40–79 years of age and in good general health and colorectal cancer was not suspected. Informative meetings were organized to explain the type of study (objectives of the study, detailed explanation of a colonoscopy). Subjects to be screened received a standard questionnaire, including questions regarding their personal medical history (including history of colorectal cancer or polyps), current medications, family history (including colorectal cancer or polyps) and lifestyle habits (including smoking and alcohol consumption). Personal interviews were conducted to ensure that screenees were asymptomatic (no recent changes in bowel habits, lower abdominal pain, unexplained weight loss, or visible rectal bleeding). Subjects with symptoms were urged to seek medical care and were excluded from the study.

We excluded the subjects with previous experience with colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy or barium enema, incomplete questionnaire answers. To ensure that the population was of average risk, we excluded individuals who had a personal history of colorectal neoplasm or inflammatory bowel disease or a family history of colorectal neoplasm. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Medica Sur Hospital.

Bowel preparation consisted of colonic lavage with a polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution (Nulytely®).

Sedation was administered in all procedures by a certified anesthesiologist with the combination of benzodiazepine (midazolam 0.05mg/kg) and propofol (induction doses 2mg/kg and bolus 0.5mg/kg).

ColonoscopyAll colonoscopies were performed by only one experienced colonoscopist by using a UC-180HD (Olympus). During colonoscopy, the location, size, number and appearance of colorectal neoplasm were recorded. Polyp size was estimated by using open biopsy forceps, and polyps shape was determined according to the Paris classification.13 All polyps seen were removed. The colonoscopist recorded the extent of the examination and the quality of the bowel preparation using the Boston score.14

Biopsy specimens were evaluated locally by a pathologist using the criteria established by the World Health Organization.15

The duration of each total examination was recorded as well as the duration of withdrawal.

The 30-day data for complications and death from colonoscopy were collected systematically.

Measurement and definitionsAn advanced neoplasm was defined as a cancer or adenoma that was at least 10mm in diameter and had high-grade displasia, villous or tubulovillous histological characteristics, or any combination thereof.

According to the recommendations of the World Health Organization, body mass index (BMI) was categorized as follows: normal (<25kg/m2), overweight (≥25 y <30kg/m2) and obese (≥30kg/m2).

Proximal adenomas were defined as those occurring in the cecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure and transverse colon. Distal adenomas were those occurring in the splenic flexure, descending colon, sigmoid colon and rectum.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables were expressed as the mean±standard deviation, and categorical variables were presented as absolute values and percentages. The differences between continuous variables were analyzed by using the unpaired Student t test, and differences between categorical variables were analyzed by using the X2 test and the Fisher exact test as appropriate. The relationship between age group and the prevalence of colorectal neoplasm was analyzed for trends by using the X2 test. A p value<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. The analyses were performed with SPSS software, version 17.0.

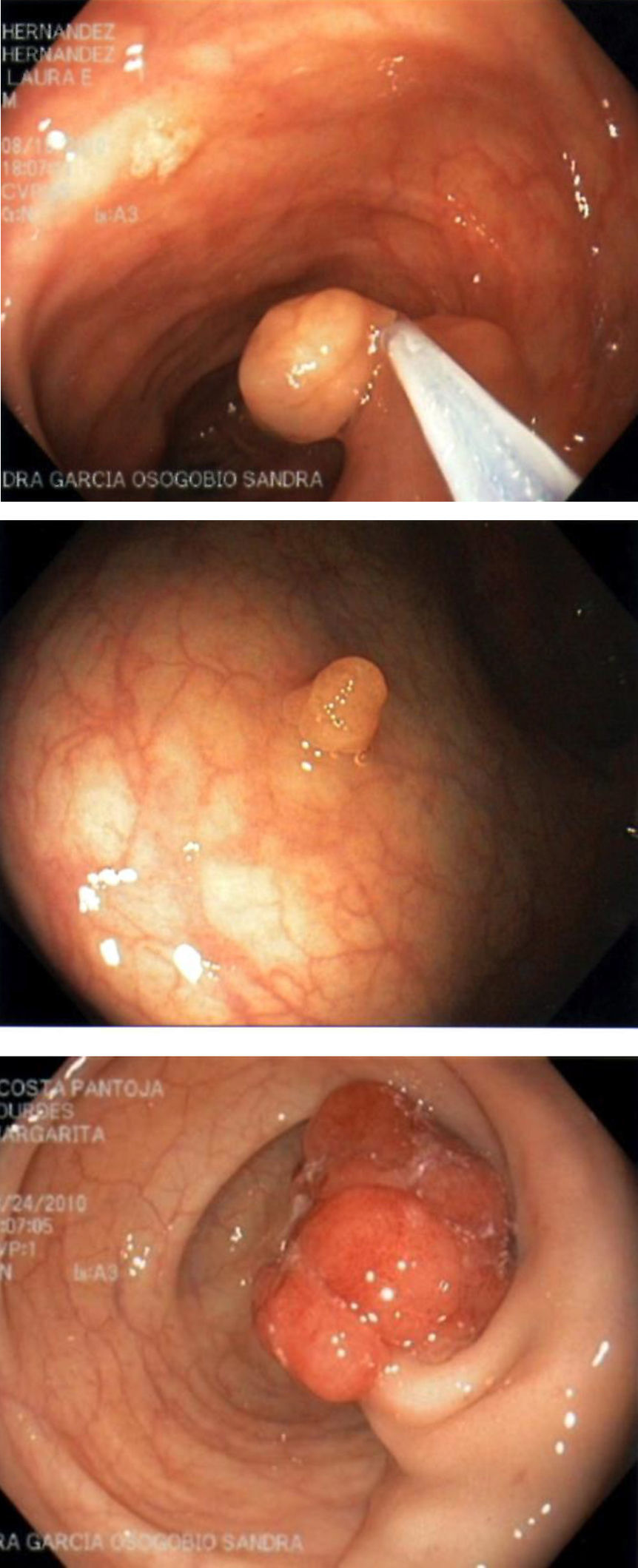

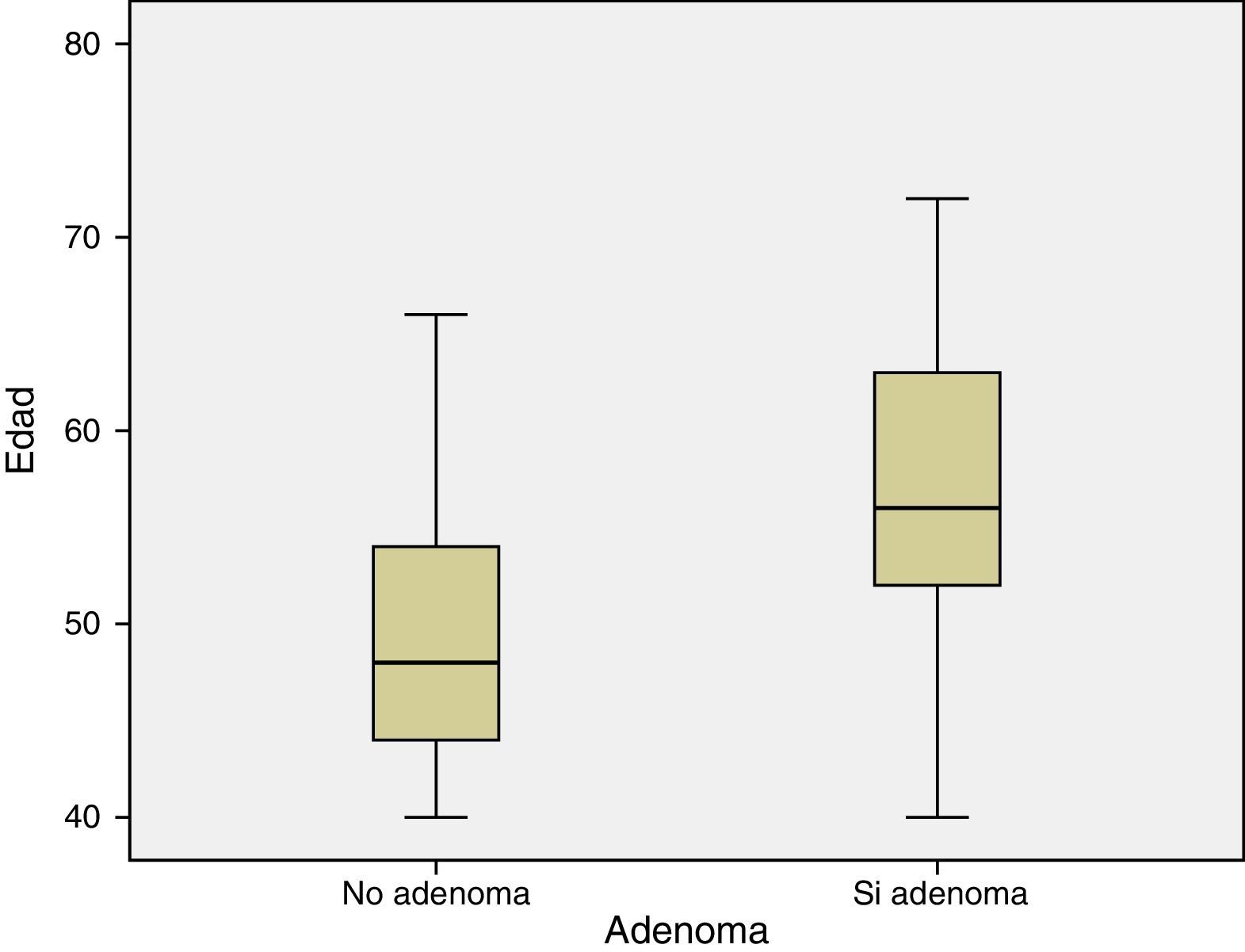

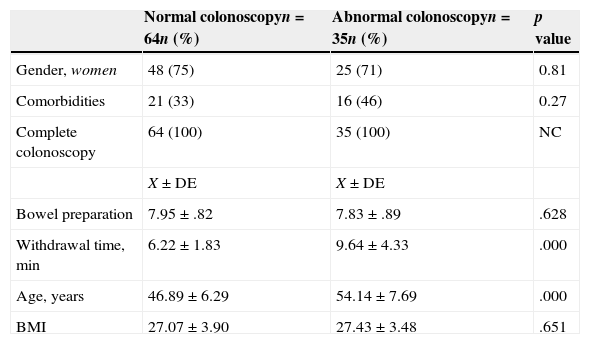

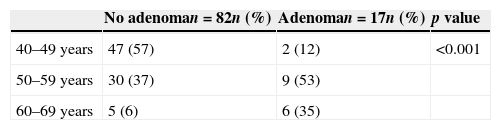

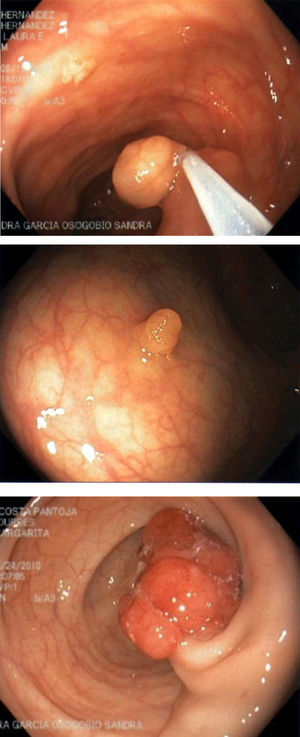

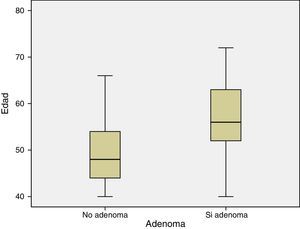

ResultsA total of 600 personalized letters were sent to employees of Medica Sur Hospital. Of these, 123 subjects responded to the invitation. We excluded 14 subjects. The reasons for exclusion were: previous colonoscopy, use of anticoagulants, and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Three subjects did not accept to participate and seven did not attend to the procedure. A total of 99 patients completed the study, 73 (74%) were women and 26 (26%) were men, with a mean (±SD) age of 50.1±7.41, with a mean of BMI of 27.20±3.74kg/m2. Thirty-seven patients had at least one comorbidity, and the most frequent was high blood pressure. Colonoscopy to the cecum was performed in all patients, and terminal ileum was intubated in 87 (87%) cases. The mean bowel preparation score was 7.91±.84. The mean duration of withdrawal was 7.43±3.34min. The demographics of the subjects included in the analysis according to the colonoscopy result are listed in Table 1. Overall, 35 (35%) patients had 47 colorectal neoplasm. Among these, there were 25 adenoma (9 were advanced adenoma) in 17 (17%) patients. Fig. 1 shows images of polyps found during colonoscopies and one image of a polypectomy. Table 2 shows the prevalence of colorectal neoplasm throughout the colon. The location of the lesions was: cecum 3 (6.3%), ascending colon 4 (8.5%), transverse 9 (19.1%), descending 9 (19.1%), sigmoid 10 (21.2%) and rectum 12 (25.5%). The median size of the neoplasm was 4mm (range 2–20). The prevalence of adenomas was analyzed by age group (Table 3), showing higher prevalence at older age (Fig. 2).

Demographics of the subjects included in the analysis according to the colonoscopy result.

| Normal colonoscopyn=64n (%) | Abnormal colonoscopyn=35n (%) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, women | 48 (75) | 25 (71) | 0.81 |

| Comorbidities | 21 (33) | 16 (46) | 0.27 |

| Complete colonoscopy | 64 (100) | 35 (100) | NC |

| X±DE | X±DE | ||

| Bowel preparation | 7.95±.82 | 7.83±.89 | .628 |

| Withdrawal time, min | 6.22±1.83 | 9.64±4.33 | .000 |

| Age, years | 46.89±6.29 | 54.14±7.69 | .000 |

| BMI | 27.07±3.90 | 27.43±3.48 | .651 |

BMI: bowel mass index (kg/m2).

The demographics of the subjects were analyzed according to the presence of adenoma and advanced adenoma, and no difference was found; however, there is a trend to have more adenoma in men (RR=2, IC95% .83–4.62, p=.139).

No complication was documented in any patient.

DiscussionOur data provide the first information, to our knowledge, on the prevalence of colorectal neoplasia in asymptomatic persons in Mexico. This study found that the prevalence of colorectal neoplasia was 35%. Specifically, the prevalence of adenomas was 17%. Adenomas were more common among men than women (26.9% vs 13.69%), and the prevalence of detected adenomas increased markedly with age-group (40–49 years vs 50–59 years). According to location of adenomas, there was no difference between proximal and distal colon (7% vs 10%).

Current guidelines suggest that adenomas should be detected in ≥15% of women and in ≥25% of men who undergo screening colonoscopy;16 however, these estimates were obtained from small referral populations. Data on the prevalence of adenomas detected in diverse populations from large community based sources estimate lower prevalence in women than in men (20.2% vs 30.6%).17 Adenoma prevalence has been used to estimate cancer risk and to identify which demographic populations may experience the highest potential benefit from adenoma removal. Unfortunately, in Mexico there is not a national screening program even knowing that CRC is the most frequent cancer within digestive neoplasias.9 We believe that our data, which are not far from the world data, could play an important role to initiate a CRC screening program. Although there are no previous data of CCR screening in our population, our data showed here are similar to that previously reported in others populations.

Strengths of the current study include the prospective nature, the inclusion of only asymptomatic patients, its use of validated approaches to screening examinations and pathology data, information on polyp size, details of bowel preparation and extent of exam.

The principal limitation of this study is the small sample size and single-center participation. However, we have to mention that our results represent the first information in this topic from a private center from Mexico and even from Latin America; because of that we are sure that these results are of big importance for future revisions.

In conclusion, the prevalence of adenomas detected at screening colonoscopy is not different to that published in world literature. The current results provide the most precise data available on the prevalence of adenomas in Mexico.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

FundingThe project was supported by grants from the Fundación Clínica Médica Sur and from Asofarma de México.