To determine the flow of care for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and hypertension between primary care (PC) and specialized care (SC) in clinical practice, and the criteria used for referral and follow-up within the Spanish National Health System (NHS).

DesignA descriptive, cross-sectional, multicenter study.

PlacementA probability convenience sampling stratified by number of physicians participating in each Spanish autonomous community was performed. Nine hundred and ninety-nine physicians were surveyed, of whom 78.1% (n=780) were primary care physicians (PCPs), while 11.9% (n=119) and 10.0% (n=100) respectively were specialists in hypertension and diabetes.

Key measurementsWere conducted using two self administered online surveys.

ResultsA majority of PCPs (63.7% and 55.5%) and specialists (79.8% and 45.0%) reported the lack of a protocol to coordinate the primary and specialized settings for both hypertension and T2DM respectively. The most widely used method for communication between specialists was the referral sheet (94.6% in PC and 92.4% in SC).

The main reasons for referral to a specialist were refractory hypertension (80.9%) and suspected secondary hypertension (75.6%) in hypertensive patients, and suspicion of a specific diabetes (71.9%) and pregnancy (71.7%) in T2DM patients.

ConclusionsAlthough results showed some common characteristics between PCPs and specialists in disease management procedures, the main finding was a poor coordination between PC and SC.

Conocer el flujo de atención entre la atención primaria y la atención especializada (AE), así como los criterios usados para la derivación y posterior seguimiento, en relación con el paciente con hipertensión arterial (HTA) y diabetes mellitus tipo 2 (DM2).

DiseñoEstudio descriptivo, transversal y multicéntrico.

EmplazamientoSe realizó un muestreo probabilístico, de conveniencia y estratificado por número de médicos en cada CCAA. Participaron 999 médicos, 78,1% (n=780) especialistas en atención primaria (EAP), 11,9% (n=119) especialistas en hipertensión y 10,0% (n=100) especialistas en diabetes.

Mediciones principalesSe emplearon 2 formularios de recogida de datos, autoadministrados vía online.

ResultadosEl 63,7% y el 55,5% de los EAP y el 79,8% y el 45,0% de la AE declararon la falta de un protocolo de coordinación entre los niveles para el manejo del paciente con HTA y DM2, respectivamente. El método de comunicación más frecuentemente usado entre los niveles asistenciales fue la hoja de derivación (94,6% en EAP y 92,4% en AE). Los principales criterios de derivación al médico de AE del paciente con HTA fueron la hipertensión resistente (80,9%) y la sospecha de hipertensión secundaria (75,6%), siendo la sospecha de DM específica (71,9%) y el embarazo (71,7%) en el paciente con DM2.

ConclusionesAunque se observaron coincidencias en algunos aspectos de la práctica clínica habitual entre ambos niveles asistenciales, las discrepancias evidenciadas mostraron una escasa coordinación entre EAP y AE.

High blood pressure (HBP) and type 2 diabetes mellitus 2 (T2DM) represent a significant socioeconomic and healthcare burden, and are both risk factors for cardiovascular disease. The prevalence of HBP and T2DM has increased due to the gradual aging of the population. In addition, factors such as obesity, the lack of regular physical activity, and unbalanced diet have contributed to the development of these diseases.1–3

The prevalence of HBP in Spain ranges from 15% to 20% in the population aged 15 years or older, and progressively increases to a rate greater than 70% in the population >65 years of age.4 T2DM accounts for 90% of cases of diabetes, with a prevalence ranging from 10% to 15% in the adult population.5,6 These diseases represent substantial costs for the Spanish healthcare system. The cost of a hypertensive patient may be up to twofold greater as compared to a normotensive subject, while the annual cost of a patient with T2DM is approximately 37% higher as compared to subjects with no diabetes7,8

According to the Spanish Society of Hypertension, 7% of the reasons for consulting primary care physicians (PCPs)9 are related to HBP, which is the main reason for consultation. T2DM is estimated to be the health problem that generates the most demand and is the most time-consuming, and is responsible for up to 29.1% of all nursing visits in primary care (PC).10

The efficient control of these diseases requires the optimum organization of care and an adequate coordination of healthcare services. In Spain, PC is the first point of contact of patients with the healthcare system, and its objective is to achieve continuous, integrated, global, and individualized care. It also serves as the entry point to specialized care (SC).

Although the healthcare system has reached a high degree of development, both in PC and SC, a deficient relationship exists between the care levels. This is mainly due to inadequate resources, the care burden, competence between levels, communication failure, and the incomplete information sometimes transmitted in referral documents.11

The deficient coordination of healthcare services has negative consequences such as ineffective resource management, decreased care quality, unnecessary referrals, the loss of the overall patient perspective, and poor disease control.12–16 All these consequences have a monetary impact, by increasing the cost of treating the disease.

The main objective of this study was to ascertain the flow of care for patients with HBP or T2DM between PC and SC physicians, and to analyze the criteria used both for referral and in the subsequent monitoring of such patients.

Materials and methodsDesignThis was a multicenter, randomized, cross-sectional, descriptive study using two questionnaires completed online by PC and SC physicians from all over Spain.

Study populationA selection was made using simple randomized sampling, with a geographical stratification in accordance with population distribution throughout Spain in order to assess the differences between the various geographical areas.

Specialists providing care to patients with HBP and T2DM and willing to participate in the study were enrolled.

A group of coordinators was formed to help develop, based on item collection from guidelines and the specialized literature, two data collection forms, one for PCPs and the other for SC physicians. Both forms consisted of three sections: the socio-demographic and occupational characteristics of the physician, data on HBP patients and data on patients with T2DM. Each physician completed the form through a computer application which was accessed using a user name and password.

Statistical analysisFrequencies and percentages with their respective 95% confidence intervals were used for qualitative variables. The sample of participants was stratified based on the geographical areas (northern, central, and southern). These geographical areas were based on the grouping of the different Nielsen areas in Spain.

Northern: area 1 (Barcelona, Gerona, Huesca, the Balearic Islands, Lleida, Tarragona, Zaragoza), area 5 (La Coruña, Asturias, León, Lugo, Orense, Pontevedra), and area 6 (Álava, Burgos, Cantabria, Gipuzkoa, La Rioja, Navarre, Palencia, Biscay).

Central: area 2 (Albacete, Alicante, Castellón, Murcia, Valencia) and area 4 (Ávila, Cáceres, Ciudad Real, Cuenca, Guadalajara, Madrid Salamanca, Segovia, Soria, Teruel, Toledo, Zamora, Valladolid).

Southern: area 3 (Almería, Badajoz, Cádiz, Cordova, Granada, Huelva, Jaén, Málaga, Seville) and area 7 (Ceuta, Las Palmas, Melilla, Santa Cruz de Tenerife).

A Fisher's test was used to compare percentages based on the geographical area. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS statistical software version 9.1.3 Service Pack 3. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsSample descriptionA total of 999 physicians from throughout Spain participated in the study. Of these, 780 (78.1%) were PCPs and 219 (21.9%) SC physicians; of the latter, 119 and 100 were specialists in HBP and T2DM respectively. The sample represented 2.7% and 0.5% respectively of all professionals in each of the care levels.17 PCPs from the northern, central, and southern areas represented 30.9%, 34.6%, and 34.5% of the total sample respectively. Of physicians specializing in HBP, 34.5%, 32.8%, and 32.8% were from the northern, central, and southern areas respectively. Finally, 33.0%, 37.0%, and 30.0% of physicians specializing in T2DM were from the northern, central, and southern areas respectively.

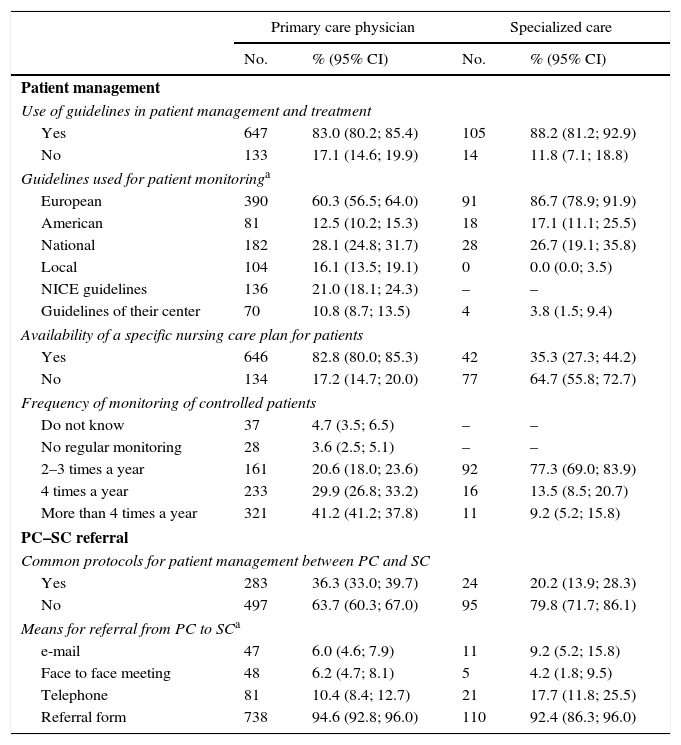

Circuit of care for hypertensive patientsThe use of guidelines for managing patients with HBP was standard practice both in PC and SC, with European guidelines18 being the most commonly used, particularly in SC (86.7%) (Table 1).

Circuit of care for hypertensive patients: primary care physician (PCP) (n=780) and specialized care (SC) physician (n=119).

| Primary care physician | Specialized care | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % (95% CI) | No. | % (95% CI) | |

| Patient management | ||||

| Use of guidelines in patient management and treatment | ||||

| Yes | 647 | 83.0 (80.2; 85.4) | 105 | 88.2 (81.2; 92.9) |

| No | 133 | 17.1 (14.6; 19.9) | 14 | 11.8 (7.1; 18.8) |

| Guidelines used for patient monitoringa | ||||

| European | 390 | 60.3 (56.5; 64.0) | 91 | 86.7 (78.9; 91.9) |

| American | 81 | 12.5 (10.2; 15.3) | 18 | 17.1 (11.1; 25.5) |

| National | 182 | 28.1 (24.8; 31.7) | 28 | 26.7 (19.1; 35.8) |

| Local | 104 | 16.1 (13.5; 19.1) | 0 | 0.0 (0.0; 3.5) |

| NICE guidelines | 136 | 21.0 (18.1; 24.3) | – | – |

| Guidelines of their center | 70 | 10.8 (8.7; 13.5) | 4 | 3.8 (1.5; 9.4) |

| Availability of a specific nursing care plan for patients | ||||

| Yes | 646 | 82.8 (80.0; 85.3) | 42 | 35.3 (27.3; 44.2) |

| No | 134 | 17.2 (14.7; 20.0) | 77 | 64.7 (55.8; 72.7) |

| Frequency of monitoring of controlled patients | ||||

| Do not know | 37 | 4.7 (3.5; 6.5) | – | – |

| No regular monitoring | 28 | 3.6 (2.5; 5.1) | – | – |

| 2–3 times a year | 161 | 20.6 (18.0; 23.6) | 92 | 77.3 (69.0; 83.9) |

| 4 times a year | 233 | 29.9 (26.8; 33.2) | 16 | 13.5 (8.5; 20.7) |

| More than 4 times a year | 321 | 41.2 (41.2; 37.8) | 11 | 9.2 (5.2; 15.8) |

| PC–SC referral | ||||

| Common protocols for patient management between PC and SC | ||||

| Yes | 283 | 36.3 (33.0; 39.7) | 24 | 20.2 (13.9; 28.3) |

| No | 497 | 63.7 (60.3; 67.0) | 95 | 79.8 (71.7; 86.1) |

| Means for referral from PC to SCa | ||||

| 47 | 6.0 (4.6; 7.9) | 11 | 9.2 (5.2; 15.8) | |

| Face to face meeting | 48 | 6.2 (4.7; 8.1) | 5 | 4.2 (1.8; 9.5) |

| Telephone | 81 | 10.4 (8.4; 12.7) | 21 | 17.7 (11.8; 25.5) |

| Referral form | 738 | 94.6 (92.8; 96.0) | 110 | 92.4 (86.3; 96.0) |

%, percentage; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; No., no. of participants.

Knowledge on the part of physicians of the existence of a specific nursing care plan was more common in PC as compared to SC (82.8% vs 35.3%). In addition, most PCPs (71%) stated that nurses monitored well controlled patients at least four times per year, while 77.3% of SC physicians reported less frequent monitoring (2–3 times per year).

According to 71.7%, HBP was monitored using procedures or protocols available at PC centers. In PC, 74.6% of physicians assessed cardiovascular risk in each patient using the Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation Project (SCORE),19,20 and 46.7% had ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) available.

A majority of PC (63.7%) and SC physicians (79.8%) thought that there were no protocols common to both care levels for the management of hypertensive patients.

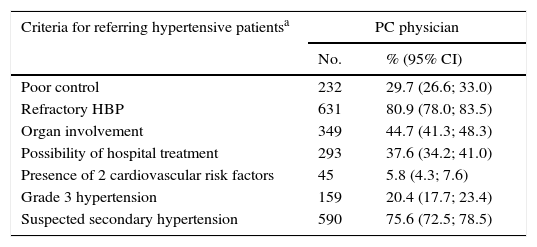

The two most common criteria for referring a patient with HBP to a specialist were “refractory HBP” and “suspected secondary HBP” (Table 2). In PC, 55.5% of physicians stated that they considered referral when patients had blood pressure (PA) levels >180/110mmHg. In both care levels, more than 90% of physicians stated that the referral form was the most commonly used means of communication.

Criteria for referring hypertensive and diabetic patients to a specialist according to PC (n=780) and SC physicians (n=100).

| Criteria for referring hypertensive patientsa | PC physician | |

|---|---|---|

| No. | % (95% CI) | |

| Poor control | 232 | 29.7 (26.6; 33.0) |

| Refractory HBP | 631 | 80.9 (78.0; 83.5) |

| Organ involvement | 349 | 44.7 (41.3; 48.3) |

| Possibility of hospital treatment | 293 | 37.6 (34.2; 41.0) |

| Presence of 2 cardiovascular risk factors | 45 | 5.8 (4.3; 7.6) |

| Grade 3 hypertension | 159 | 20.4 (17.7; 23.4) |

| Suspected secondary hypertension | 590 | 75.6 (72.5; 78.5) |

| Criteria for referring diabetic patientsa | PC physician | SC physician | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % (95% CI) | No. | % (95% CI) | |

| Poor control | 476 | 61.0 (57.6; 64.4) | 82 | 82.0 (73.3; 88.3) |

| Complex treatment regimens | 242 | 31.0 (27.9; 34.4) | 17 | 17.0 (10.9; 25.6) |

| Frequent hypoglycemia | 266 | 34.1 (30.9; 37.5) | 26 | 26.0 (18.4; 35.4) |

| Severe hypoglycemia | 291 | 37.3 (34.0; 40.8) | 29 | 29.0 (21.0; 38.5) |

| When starting treatment with OADs with the presence of IR | 62 | 8.0 (6.3; 10.1) | 20 | 20.0 (13.3; 28.9) |

| Start of insulin therapy | 76 | 9.7 (7.9; 12.0) | 5 | 5.0 (2.2; 11.2) |

| Suspected specific DM | 561 | 71.9 (68.7; 75.0) | 3 | 3.0 (1.0; 8.5) |

| Pregnancy in a diabetic woman | 559 | 71.7 (68.4; 74.7) | 8 | 8.0 (4.1; 15.0) |

| Patients under 40 years with possible T1DM at diagnosis | 487 | 62.4 (59.0; 65.8) | 8 | 8.0 (4.1; 15.0) |

| At diagnosis in order to define a joint action scheme | 35 | 4.5 (3.2; 6.2) | 1 | 1.0 (0.2; 5.5) |

SC, specialized care; OADs, oral antidiabetic drugs; DM, diabetes mellitus; PC, primary care; No., frequencies; %, percentage; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

More than half of the participants stated that once the patient was referred to SC, nephrology was the department responsible both for the monitoring (55.5%) and treatment (52.9%) of refractory HBP. As regards the monitoring of poorly controlled hypertensive patients by the specialist, only 11.8% used telemedicine, while 57.1% used the platforms available in their healthcare area.

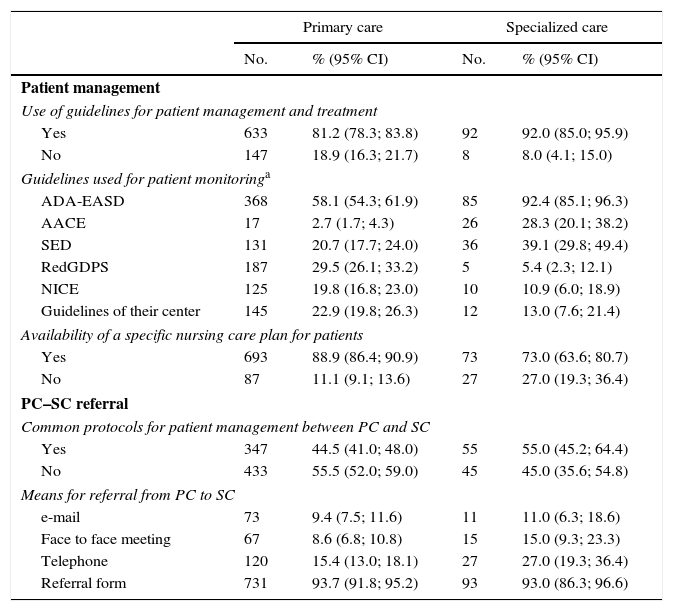

Circuit of care for diabetic patientsA high proportion of PC and SC physicians used guidelines on the management and treatment of diabetic patients, of which the ADA-EASD guidelines21 were the most widely used, by 58.1% of PCPs and 92.4% of SC physicians (Table 3). Similarly, for HBP 77.4% stated that the monitoring of diabetic patients was based on procedures and protocols implemented at PC centers. A specific nursing care plan was reported to exist by 88.9% and 73% of PC and SC physicians. Among PCPs, 77.7% stated that well controlled patients were monitored by nursing at least four times a year. Sixty-two percent of SC physicians stated that well controlled patients were monitored 2–3 times a year, while 81% said that the frequency was increased to at least four times a year in patients with poor metabolic control.

Circuit of care for diabetic patients: primary care physicians (n=780) and specialized care (SC) physicians (n=100).

| Primary care | Specialized care | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % (95% CI) | No. | % (95% CI) | |

| Patient management | ||||

| Use of guidelines for patient management and treatment | ||||

| Yes | 633 | 81.2 (78.3; 83.8) | 92 | 92.0 (85.0; 95.9) |

| No | 147 | 18.9 (16.3; 21.7) | 8 | 8.0 (4.1; 15.0) |

| Guidelines used for patient monitoringa | ||||

| ADA-EASD | 368 | 58.1 (54.3; 61.9) | 85 | 92.4 (85.1; 96.3) |

| AACE | 17 | 2.7 (1.7; 4.3) | 26 | 28.3 (20.1; 38.2) |

| SED | 131 | 20.7 (17.7; 24.0) | 36 | 39.1 (29.8; 49.4) |

| RedGDPS | 187 | 29.5 (26.1; 33.2) | 5 | 5.4 (2.3; 12.1) |

| NICE | 125 | 19.8 (16.8; 23.0) | 10 | 10.9 (6.0; 18.9) |

| Guidelines of their center | 145 | 22.9 (19.8; 26.3) | 12 | 13.0 (7.6; 21.4) |

| Availability of a specific nursing care plan for patients | ||||

| Yes | 693 | 88.9 (86.4; 90.9) | 73 | 73.0 (63.6; 80.7) |

| No | 87 | 11.1 (9.1; 13.6) | 27 | 27.0 (19.3; 36.4) |

| PC–SC referral | ||||

| Common protocols for patient management between PC and SC | ||||

| Yes | 347 | 44.5 (41.0; 48.0) | 55 | 55.0 (45.2; 64.4) |

| No | 433 | 55.5 (52.0; 59.0) | 45 | 45.0 (35.6; 54.8) |

| Means for referral from PC to SC | ||||

| 73 | 9.4 (7.5; 11.6) | 11 | 11.0 (6.3; 18.6) | |

| Face to face meeting | 67 | 8.6 (6.8; 10.8) | 15 | 15.0 (9.3; 23.3) |

| Telephone | 120 | 15.4 (13.0; 18.1) | 27 | 27.0 (19.3; 36.4) |

| Referral form | 731 | 93.7 (91.8; 95.2) | 93 | 93.0 (86.3; 96.6) |

%, percentage; SC, specialized care; PC, primary care; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; n, frequencies.

Similar proportions of PC and SC physicians reported that there were no common protocols available for the management of diabetic patients. The most common means of communication was the referral form (94.62% and 92.4%).

The most common reasons for referral from PC to SC included “suspected specific DM” (71.9%), “pregnancy in a diabetic woman” (71.7%), “patient under 40 years with possible T1DM at diagnosis” (62.4%), and “poor diabetes control” (61.0%). It should be noted that approximately 75% of PCPs said that they would refer a diabetic patient with HBP to SC if BP was >150/100mmHg (Table 2).

Most SC physicians (82.0%) thought that patients with T2DM should be controlled by SC if they were “poorly controlled”, and reported frequent (26.0%) or severe (29.0%) hypoglycemia as referral criteria. Unlike PCPs, few specialists considered “suspected specific DM” (3.0%), “pregnancy in a diabetic woman” (8.0%) or “patients under 40 years with possible T1DM at diagnosis” (8.0%) as referral criteria. Approximately 90% stated that the department of endocrinology was responsible for patients with difficult T2DM control.

Five percent of SC physicians used telemedicine for monitoring patients with poorly controlled T2DM, and 60.0% of them used the platforms available in their healthcare area.

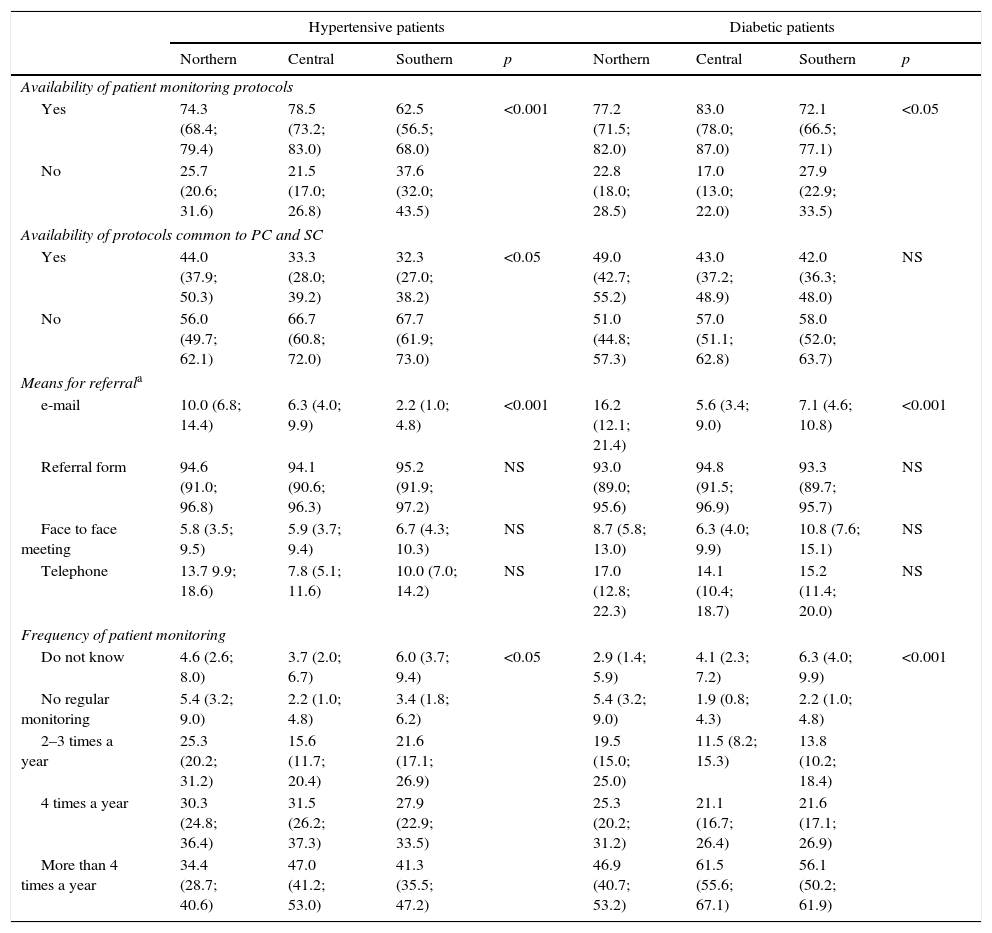

Differences by geographical areaTable 4 shows the differences in the management of hypertensive and diabetic patients by geographical area. For both types of patient, fewer protocols for patient monitoring in PC were available in the southern area.

Differences between geographical areas in primary care.

| Hypertensive patients | Diabetic patients | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern | Central | Southern | p | Northern | Central | Southern | p | |

| Availability of patient monitoring protocols | ||||||||

| Yes | 74.3 (68.4; 79.4) | 78.5 (73.2; 83.0) | 62.5 (56.5; 68.0) | <0.001 | 77.2 (71.5; 82.0) | 83.0 (78.0; 87.0) | 72.1 (66.5; 77.1) | <0.05 |

| No | 25.7 (20.6; 31.6) | 21.5 (17.0; 26.8) | 37.6 (32.0; 43.5) | 22.8 (18.0; 28.5) | 17.0 (13.0; 22.0) | 27.9 (22.9; 33.5) | ||

| Availability of protocols common to PC and SC | ||||||||

| Yes | 44.0 (37.9; 50.3) | 33.3 (28.0; 39.2) | 32.3 (27.0; 38.2) | <0.05 | 49.0 (42.7; 55.2) | 43.0 (37.2; 48.9) | 42.0 (36.3; 48.0) | NS |

| No | 56.0 (49.7; 62.1) | 66.7 (60.8; 72.0) | 67.7 (61.9; 73.0) | 51.0 (44.8; 57.3) | 57.0 (51.1; 62.8) | 58.0 (52.0; 63.7) | ||

| Means for referrala | ||||||||

| 10.0 (6.8; 14.4) | 6.3 (4.0; 9.9) | 2.2 (1.0; 4.8) | <0.001 | 16.2 (12.1; 21.4) | 5.6 (3.4; 9.0) | 7.1 (4.6; 10.8) | <0.001 | |

| Referral form | 94.6 (91.0; 96.8) | 94.1 (90.6; 96.3) | 95.2 (91.9; 97.2) | NS | 93.0 (89.0; 95.6) | 94.8 (91.5; 96.9) | 93.3 (89.7; 95.7) | NS |

| Face to face meeting | 5.8 (3.5; 9.5) | 5.9 (3.7; 9.4) | 6.7 (4.3; 10.3) | NS | 8.7 (5.8; 13.0) | 6.3 (4.0; 9.9) | 10.8 (7.6; 15.1) | NS |

| Telephone | 13.7 9.9; 18.6) | 7.8 (5.1; 11.6) | 10.0 (7.0; 14.2) | NS | 17.0 (12.8; 22.3) | 14.1 (10.4; 18.7) | 15.2 (11.4; 20.0) | NS |

| Frequency of patient monitoring | ||||||||

| Do not know | 4.6 (2.6; 8.0) | 3.7 (2.0; 6.7) | 6.0 (3.7; 9.4) | <0.05 | 2.9 (1.4; 5.9) | 4.1 (2.3; 7.2) | 6.3 (4.0; 9.9) | <0.001 |

| No regular monitoring | 5.4 (3.2; 9.0) | 2.2 (1.0; 4.8) | 3.4 (1.8; 6.2) | 5.4 (3.2; 9.0) | 1.9 (0.8; 4.3) | 2.2 (1.0; 4.8) | ||

| 2–3 times a year | 25.3 (20.2; 31.2) | 15.6 (11.7; 20.4) | 21.6 (17.1; 26.9) | 19.5 (15.0; 25.0) | 11.5 (8.2; 15.3) | 13.8 (10.2; 18.4) | ||

| 4 times a year | 30.3 (24.8; 36.4) | 31.5 (26.2; 37.3) | 27.9 (22.9; 33.5) | 25.3 (20.2; 31.2) | 21.1 (16.7; 26.4) | 21.6 (17.1; 26.9) | ||

| More than 4 times a year | 34.4 (28.7; 40.6) | 47.0 (41.2; 53.0) | 41.3 (35.5; 47.2) | 46.9 (40.7; 53.2) | 61.5 (55.6; 67.1) | 56.1 (50.2; 61.9) | ||

NS, no statistically significant differences. All results are percentages (95% confidence interval).

Throughout Spain, communication between PC and SC mainly occurred through the referral forms. While electronic mail was only occasionally used as compared to all the other communication channels, it was the only means for which statistically significant differences were found between geographical areas both for hypertensive (p<0.001) and diabetic patients (p<0.001). Electronic mail was most commonly used in the northern area.

An analysis of PCP answers referring to the management of patients with HBP found no differences in the use of guidelines in standard practice, but different specific guidelines were used. Thus, the European guidelines18 were mainly used in the central area (66.7%), NICE guidelines22 in the southern area (26.7%), and local guidelines in the northern area (20.8%; p<0.05).

Differences were also found in the stratification method used: the SCORE tables19,20 in the central area (86.7%; p<0.001), Framingham23,24 in the southern area (39.0%; p<0.05), and REGICOR23,25 in the northern area (29.5%; p<0.001). The performance of ABPM was most common in the northern area (62.7%; p<0.001).

A greater proportion of SC physicians in the central area stated that the cardiology (10.8%) and nephrology departments (13.5%) were responsible for the treatment and monitoring of patients with poorly controlled HBP (p<0.05 and p<0.01 respectively).

An analysis of PCP answers referring to diabetic patients showed differences in the specific guidelines used in standard clinical practice. The use of the redGDPS (Spanish Network of Primary Care Groups for the Study of Diabetes) guidelines was least common in the southern area26 (21.8%; p<0.01).

As regards the criteria for referring patients with T2DM from PC to SC, significant differences were only found for the criteria “pregnancy in a diabetic woman” (p<0.01), “severe hypoglycemia” (p<0.05), and “complex treatment regimens” (p<0.05). These three criteria were mentioned less frequently in the southern area (63.6%, 31.6%, and 27.5% respectively).

DiscussionThe results of this study reflect the perception of circuits of care for hypertensive and diabetic patients in the Spanish national health system, showing the points which are common to both care levels and discrepancies in the management of these patients.

In PC, stratification based on an assessment of individual risk is usually made. This helps in making decisions for disease management and in avoiding either deficient or excessive forms of treatment. In line with suggestions made in the European guidelines for cardiovascular prevention in clinical practice, the SCORE tables19,20,27,28 are the method most commonly used in Spain by PCPs for the stratification of patients with HBP, especially in the northern area.

Both PC and SC teams include nurses who are responsible for patient monitoring, among other tasks.29 Protocols establishing the role of the nursing staff were more frequently available in PC than in SC, and included a specific nursing plan for patient monitoring.

Patient monitoring by the nursing staff should occur at flexible intervals, both because of differences between patients and due to changes in the same patient. In this study, a majority of patients with HBP and T2DM were monitored by PC nursing staff at least four times a year when they were well controlled, which agrees with the recommendation by Sampedro (2006).30 By contrast, the specialist physicians surveyed in this study reported that well controlled patients were monitored at SC 2–3 times a year.

While the availability of common protocols including referral criteria and communication channels are factors contributing to adequate coordination between PC and SC, thus favoring global, individualized, integrated, continuous, and effective care, our results show an absence of or even ignorance about such common protocols in the Spanish health system, especially in the southern region. These results are similar to those found in other studies where 68.2% of PCPs stated that there was no coordination protocol with SC for the referral of patients with T2DM.31

The implementation of common criteria for the referral to SC is essential for continued healthcare which allows for treatment optimization and disease control. It is estimated that 4–6% of patients attending PC are referred.11,32,33 Various studies have assessed the specialties to which referrals are most common. In the Franquelo-Morales study (2008),34 these specialties were orthopedic surgery, ophthalmology, gynecology, and dermatology. This agrees with the report by Rubio-Arribas (2000).35 It should be noted that HBP and T2DM, which are diseases with a significant prevalence, do not coincide with the specialties to which referrals are most commonly made. Rubio-Arribas (2000)35 stated that the reason for this may be that referral is not always dictated by the complexity of the process, but rather by the training level in one or the other specialty or the willingness to assume a greater or lesser work load. In agreement with previous reports, the main criteria for the referral of patients with HBP mentioned in this study were refractory hypertension and suspected secondary hypertension, mainly because of the attendant severity, or difficult diagnosis and treatment.32 As regards return referrals, other studies show, in agreement with our results, that the most common referral criterion was achievement of the goal.31

On the other hand, adequate communication channels are essential for achieving coordination between PC and SC physicians. In this study, the referral form was the main means of communication between PC and SC physicians regarding patients with both HBP and T2DM. Other studies also report this document as the main means used.11,31,35

Clinical practice guidelines are a tool that provides many benefits. Guidelines compile evidence and recommendations intended to provide diagnosis, classification, and the adequate treatment of patients, thus optimizing the efficiency of the system. In addition, the Saéz study (2012)7 estimated that lack of HBP control increased unit cost by 13.0%. In patients with poorly controlled T2DM, costs may be up to three times higher.8

Different studies conducted in Spain have reported that physicians are aware of the recommendations in the guidelines and agree with them, but do not follow them. The PRETEND36 study showed that 30–40% of physicians follow the guidelines only occasionally or hardly ever. In the González-Juanatey study (2006),37 only 10–15% of PCPs used the guidelines. In this study, very high proportions of both PC and SC physicians followed guidelines on the management or treatment of patients with HBP and TD2M, but geographical differences existed in the guidelines used. A study conducted by Gómez (2006)38 showed that the implementation of guidelines improved the cardiovascular risk of patients.

It should finally be noted that less than half the PCPs stated that they had ABPM available at their centers, although the proportion exceeded 60% in the northern area. ABPM is an appropriate procedure for adequate HBP management because it allows for the identification of BP parameters in different monitoring periods. For this reason it should be made more readily available.1 As regards BP management, it has been shown that approximately 75% of PCPs would refer to SC a diabetic patient with BP>150/100mmHg, while the remaining 25% would do so with values ranging from 140/90 to 149/99.

The study limitations include the probability convenience sampling used, which may lead to biased results, thus making their generalization difficult. It should be emphasized, however, that the response rate was 100%, which gives more robustness to the conclusions because of the large sample size. It should also be noted that not all the comparisons made in this study were based on statistical tests, and do not have a significance value assigned, although cautious interpretations may be made using the confidence intervals of the different percentages.

Our results demonstrate that although the Spanish healthcare system has substantially improved in recent years and reached a high level of development, communication between care levels continues to be poor. The achievement of a high degree of coordination between PC physicians and SC should be a primary goal, because this would lead to multiple benefits, including a decreased social and economic impact of the disease. The relationship between physicians from both care levels should be regular and horizontal, leaving behind the concept of hierarchization traditionally associated with the relationship between the levels and imposing instead the concept of continuity between them. Future studies focusing on methods for improving circuits of care between both levels and on the implementation of new communication technologies are needed. Activities to achieve good relations between care levels should be based on organizational actions undertaken by all the professionals involved in such relations.

AuthorshipAll the authors substantially and equally participated in the study design and the writing of the article, and they have all approved the final version of the manuscript.

FundingThis study was funded by Abbott.

Conflicts of interestThe authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors thank Outcomes’10 for its collaboration during project development and its support in the critical review of the manuscript.

Please cite this article as: Alonso-Moreno FJ, Martell-Claros N, de la Figuera M, Escalada J, Rodríguez M, Orera L. Percepción de profesionales sobre los circuitos asistenciales del paciente hipertenso o diabético entre la atención primaria y atención especializada. Endocrinol Nutr. 2016;63:4–13.