To analyze the clinical features, diagnostic procedures, treatment, and clinical outcome of insulinomas diagnosed and treated in the period 1983–2014 in four Spanish hospitals.

MethodsAll patients with either biochemical and morphological criteria of insulinoma and/or histological demonstration of insulin-secreting tumor were included.

ResultsTwenty-nine patients [23 women (79.3%); mean age 48.7±17.4 years (range, 16–74)] were recruited. Twenty-six patients (89.7%) had sporadic tumors, and the rest (3 women, 10.3%) developed in the context of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. There were 3 (10.3%) multiple insulinomas, one associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, and two (6.9%) malignant insulinomas, both sporadic. Most patients (n=18, 62.1%) had fasting hypoglycemia, about a third (31%) both postprandial and fasting hypoglycemia, and 6.9% postprandial hypoglycemia only. Time to glucose nadir (37.3±6.5mg/dl) in the fasting test was 9.0±4.4h, with maximal insulin levels of 25.0±20.3μU/ml. Abdominal CT detected insulinoma in 75% of patients. Twenty-seven (93.1%) patients underwent surgery [enucleation, 18 (66.7%) and subtotal pancreatectomy, 9 (33.3%); tumor size, 1.7±0.7cm]. Surgery achieved cure in the majority (n=24, 88.9%) of patients.

ConclusionIn our setting, insulinoma is usually a benign, small, and solitary tumor, mainly affecting women aged 45–50 years, and usually localized with abdominal CT. The most commonly used surgical technique is enucleation, which achieves a high cure rate.

Analizar las características clínicas, metodología diagnóstica, tratamientos empleados y resultados de los casos de insulinoma diagnosticados y tratados entre 1983-2014 en 4 centros hospitalarios españoles.

MétodosSe incluyeron en el estudio todos los pacientes que tenían demostración histológica de tumor secretor de insulina o criterios diagnósticos bioquímicos y morfológicos de insulinoma.

ResultadosSe estudiaron 29 pacientes (23 mujeres [79,3%]; edad media 48,7±17,4 años [intervalo 16-74]). En 26 (89,7%) casos el tumor fue esporádico y en el resto (3 mujeres, 10,3%) se presentó en el contexto de una neoplasia endocrina múltiple tipo 1. Hubo 3 (10,3%) insulinomas múltiples, uno de ellos asociado a neoplasia endocrina múltiple tipo 1, y 2 (6,9%) insulinomas malignos, ambos esporádicos. La mayoría (n=18, 62,1%) mostró hipoglucemia de ayuno, aproximadamente un tercio (31%) hipoglucemia tanto de ayuno como posprandial y el 6,9% solo hipoglucemia posprandial. El tiempo en alcanzar el nadir de glucosa (37,3±6,5mg/dl) en la prueba de ayuno fue 9,0±4,4h, con insulinemia de 25,0±20,3μU/ml. La TAC abdominal localizó el insulinoma en el 75% de los casos. El 93,1% (n=27) de los pacientes fue intervenido quirúrgicamente (enucleación, 18 [66,7%] y pancreatectomía parcial, 9 [33,3%] pacientes; tamaño tumor 1,7±0,7cm). La cirugía consiguió la curación en la mayoría (n=24, 88,9%) de los pacientes.

ConclusiónEl insulinoma en nuestro medio es un tumor benigno, de pequeño tamaño y solitario, que afecta más a mujeres entre 45-50 años y que se localiza generalmente con TAC abdominal. La cirugía mediante enucleación constituye el método terapéutico más habitual consiguiendo unas altas tasas de curación.

Tumor hypoglycemia is an uncommon clinical condition that may occur in patients with different types of malignancies and result from different pathogenetic mechanisms.1 These include insulin secretion by tumors of pancreatic islet beta cells (insulinoma) and ectopic secretion by tumors in other locations, such as bronchial carcinoids and gastrointestinal tumors.

Insulinoma is the most common cause of tumor hypoglycemia.1 It is an uncommon tumor, with an incidence of four cases per million population/year. It is, however, the most common functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (PNET).2 In the past 50 years, approximately one hundred series of insulinomas evaluating about 6000 patients have been reported.3 It is usually an insulin-secreting sporadic tumor (90%) which manifests as hypoglycemia. The quantification of serum levels of glucose, proinsulin, C-peptide, and proinsulin helps in establishing a diagnosis of hypoglycemia associated with endogenous hyperinsulinism. Different imaging methods and invasive and noninvasive function tests make it possible to locate insulinoma before or after surgery, helping to establish the therapeutic strategy in most cases. Tumor enucleation is usually curative, and recurrence is exceptional. Benign insulinoma is not associated with increased mortality, and malignant insulinoma may be associated with long survival times.3

In Spain, insulinoma accounts for 8% of cases of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs), according to data from the National Register of GEP-NET published in 2010.4 Few series of insulinoma cases have been reported in Spain, and have usually included a small number of patients (<10) from a single hospital.5–7 The purpose of our study was to retrospectively review the clinical characteristics, diagnostic methods, treatments used, and results of cases of insulinoma diagnosed and treated from 1983 to 2014 in four Spanish hospitals.

Patients and methodsPatientsA retrospective study was conducted of insulinomas diagnosed and treated from 1983 to 2014 in the endocrinology departments of four Spanish hospitals: Ramón y Cajal (Madrid), Virgen de la Concha (Zamora), Nuestra Señora de Sonsoles (Ávila), and Hospital General (Segovia). For this purpose, all cases of insulinoma recorded in each of the endocrinology departments during the study period were analyzed, and the clinical histories of the patients were reviewed.

The study inclusion criteria were histological evidence of the tumor and/or the presence of biochemical and morphological criteria consistent with insulinoma. Biochemical criteria included symptomatic hypoglycemia, either spontaneous or after fasting (blood glucose <55mg/dl with Whipple's triad), associated with endogenous hyperinsulinism (insulinemia ≥3mU/ml and C peptide ≥0.2nmol/l), the absence of oral antidiabetics in serum and/or urine during hypoglycemia, negative insulin antibodies, and no history of gastrointestinal surgery. The presence of one or several images consistent with insulinoma in the location study was considered a morphological criterion.

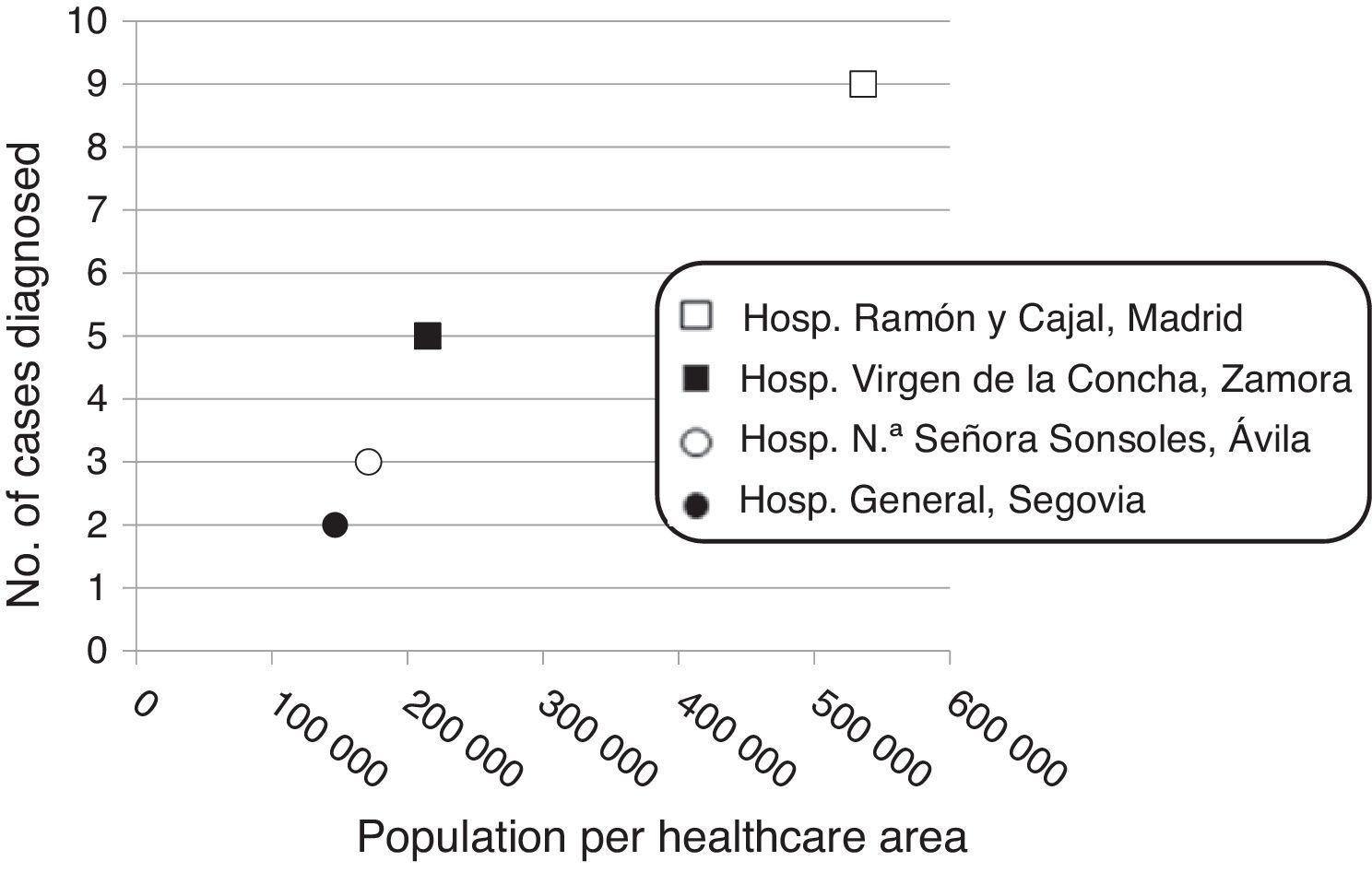

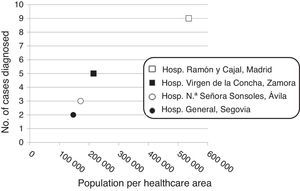

Patient distribution in the study hospitals was as follows: Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid: n=19 (9 from the healthcare area, population 536,071, and 10 from other hospitals); Hospital Virgen de la Concha, Zamora: n=5 (population, 214,768); Hospital Nuestra Señora de Sonsoles, Ávila: n=3 (population, 171,265); and Hospital General, Segovia: n=2 (population, 146,554). Twenty-five (86.2%) patients were followed up for at least one month (median, 53 months; range, 1–378).

MethodsThe following clinical parameters were collected for each patient: age at diagnosis, personal and family history, drugs at diagnosis, the presence or absence of multiple endocrine neoplasia, the reason for consultation, the signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia, the type of hypoglycemia (fasting and/or postprandial), capillary blood glucose (mean of the lowest three measurements), the estimated number of hypoglycemic episodes/month, physical examination data (weight, height, and blood pressure), essential chemistry tests, and baseline hormone measurements (insulin and C peptide) performed at the reference hospitals of each hospital with their respective normal ranges.

Functional tests included a prolonged fasting test (72h) and a glucagon test for glucose after fasting (positive response for insulinoma, increase in blood glucose ≥25mg/dl within 20–30min of administration of 1mg IV of glucagon). Location studies included (1) noninvasive tests: transabdominal ultrasonography, abdominal computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), octreoscan, and positron emission tomography (PET); and (2) invasive tests: endoscopic ultrasound, arteriography, intra-arterial calcium injection, and intraoperative pancreatic ultrasonography. Indications for each of these tests were established by the physician in charge of each patient based on clinical criteria and scientific evidence.

Surgery date, type, and procedure and surgical complications were recorded. Any medical treatment given was also evaluated. Histopathological findings were also investigated, and tumors were classified by number, size, and grade of malignancy (G1: <2 mitoses per 10 high-power fields and/or Ki-67 index ≤2%; G2: 2–20 mitoses per 10 high-power fields and/or Ki-67 index 3–20; and G3: >20 mitoses per 10 high-power fields and/or Ki-67 index >20) and TNM staging.8 The immunohistochemical study of insulinomas was also recorded when performed. Finally, each patient was evaluated on the day of his/her last revision. This was done by analyzing the laboratory data, the need for medical treatment or otherwise, and the presence or absence of a cure, provided that at least three months after surgery the patient met the following criteria in the absence of treatment for insulinoma: (1) no symptoms of hypoglycemia; (2) fasting plasma blood glucose >50mg/dl; and (3) plasma insulin <6μU/ml. Relapse-free survival was defined as the time after surgery with no tumor recurrence, and overall survival was analyzed recording patient mortality until December 31, 2014.

Statistical analysisSPSS 15.0 software was used for statistical data analysis. Quantitative variables are given as mean±SD for normally distributed data and as median (interquartile range) for nonparametric variables. The adjustment of variables to a normal distribution was performed using a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Categorical variables are given as percentages. Proportions were compared using a Chi-squared test and a Fisher's exact test when required. Correlations between quantitative variables were analyzed using Pearson's correlation analysis. Quantitative variables were compared using a Student's t test and a Wilcoxon test for normally and non-normally distributed data respectively. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

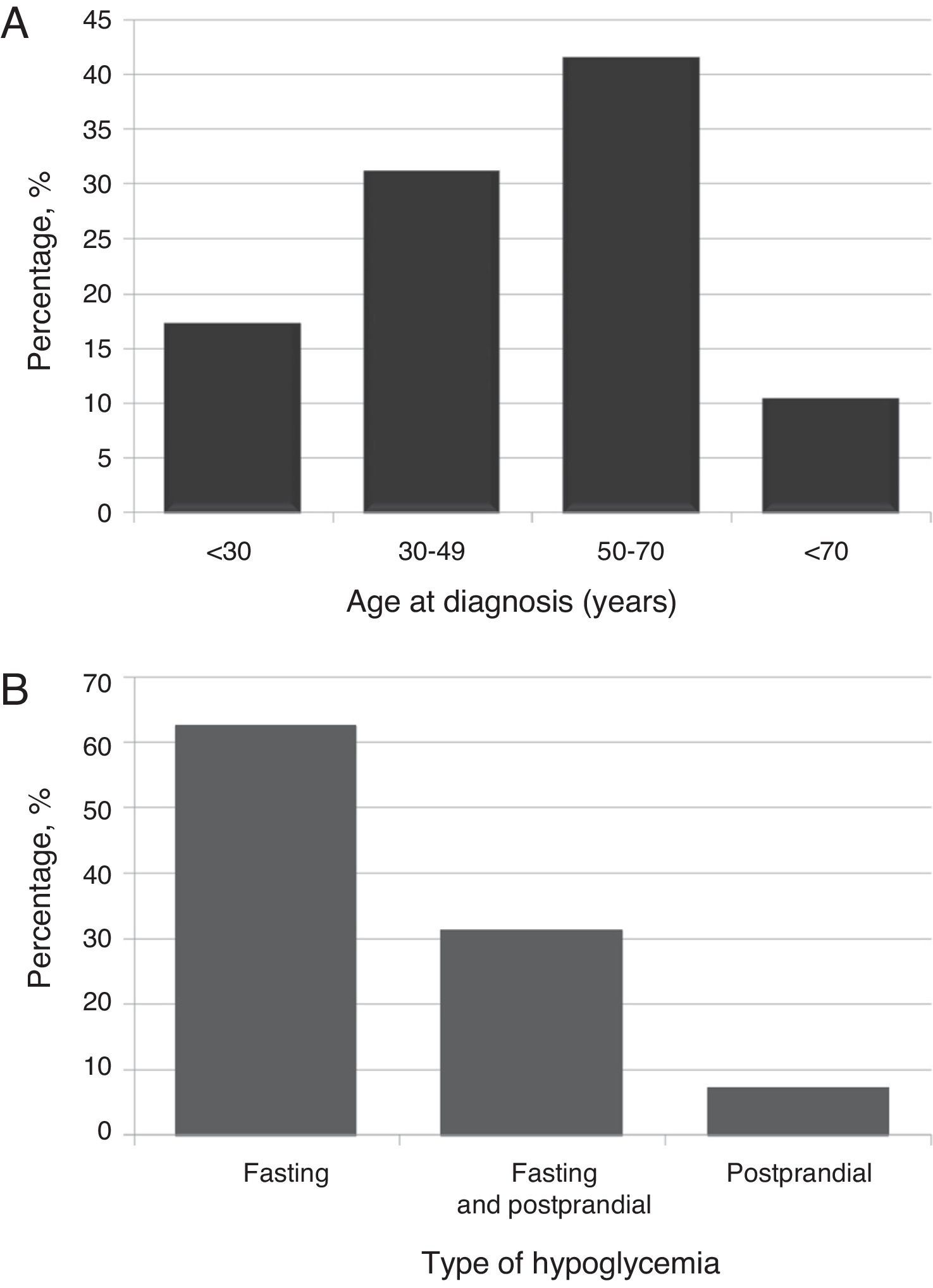

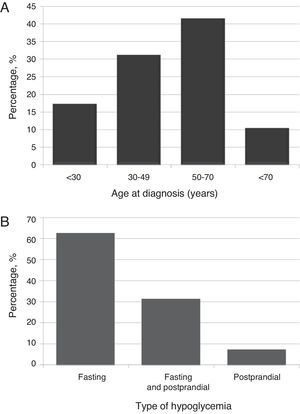

ResultsClinical and demographic characteristicsTwenty-nine patients (23 females [79.3%]; mean age 48.7±17.4 years [range, 16–74], body mass index 28.5±5.6kg/m2 [range, 22.9–45.8]). Most patients (41.4%) were diagnosed at ages ranging from 50 to 70 years (Fig. 1A).

Sporadic tumors occurred in 26 patients (89.7%), while in the remaining three female patients (10.3%) the tumor occurred in the setting of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN 1). The three patients with insulinoma associated with MEN 1 had primary hyperparathyroidism prior to the diagnosis of insulinoma; only one of them also had a non-functioning pituitary adenoma. There were three patients (10.3%, two females) with multiple insulinomas, one of them associated with MEN 1, and two patients (6.9%, two females aged 48 and 65 years respectively) with malignant insulinomas, both sporadic.

In order to assess the trend over time in the incidence of insulinoma, the study period was divided into two parts: nine patients (31%) were diagnosed in the first 15 years of the study period (1983–1998), and the remaining patients (n=20, 69%) in the last 15 years (1999–2014). A positive correlation (r=0.967; p=0.033) was found between the number of insulinomas diagnosed at each hospital and the population covered by each hospital (Fig. 2).

The time from symptom onset to diagnosis was 7.5 (5–12.5) months. Neuroglycopenic symptoms (confusion [n=20, 69%] and behavioral changes [n=13, 44.8%]) were most common. Approximately half the patients (n=14, 48.3%) consulted for a single symptom, while approximately 20% (n=5, 17.2%) reported at least 5 symptoms.

Most patients (n=18, 62.1%) experienced fasting hypoglycemia, approximately one third (31%) both fasting and postprandial hypoglycemia, and 6.9% postprandial hypoglycemia only (Fig. 1B). Hypoglycemia, both fasting and postprandial, occurred in benign insulinoma only. The type of hypoglycemia was not associated with sex, age, BMI, uni- or multifocality, or insulinoma size. However, a significant (p=0.039) association was found with the benign or malignant nature of the tumor, with benign insulinoma being the only one with both types of hypoglycemia.

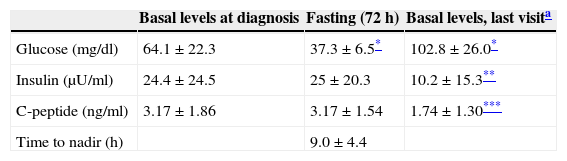

Hormone testing and function testsTable 1 shows basal plasma glucose, insulin, and C-peptide levels. No significant differences were found in plasma glucose and insulin levels or in the insulin/blood glucose ratio between females and males. Insulin positively correlated to C-peptide (r=0.757, p<0.01). Proinsulin levels, measured in five patients, were 102.5±93.5pmol/l (normal <8pmol/l), and the percent proinsulin/insulin ratio was 252.6±189.1% (normal <25%).

Basal blood glucose, insulin, and C-peptide levels at diagnosis, at the end of the prolonged fasting test (72h), and on the last visit.

The prolonged fasting test (72h) was performed in 24 patients (82.8%). The glucose nadir (37.3±6.5mg/dl; range, 24–48) in the prolonged fasting test was achieved at 9.0±4.4h (range, 0–16). Table 1 shows insulin and C-peptide levels at the end of the fasting test. Only blood glucose at the end of fasting was significantly different from baseline (p<0.001). Plasma ketones at the end of fasting, measured in three patients, were negative. The glucagon test for glucose after fasting was performed in four patients (13.8%). A 2.3±0.7-fold increase (range, 1.2–2.9) was seen in the blood glucose level at 10 min as compared to the value seen at the end of fasting (80.2±8.4mg/dl versus 37±7.3mg/dl, p<0.03).

Location studiesNoninvasive tests were performed in all patients. By decrease in frequency, the tests were as follows: CT (n=29, 100%), transabdominal ultrasonography (n=14, 48.3%), octreoscan (n=14, 48.3%), MRI (n=11, 37.9%), and PET (n=4, 13.8%). Invasive tests were performed in 16 patients (55.2%) (endoscopic ultrasound, 7 [24.1%; three of them underwent ultrasound-guided FNA with a result consistent with neuroendocrine tumor], arteriography, 7 [24.1%]; intraoperative ultrasonography, 5 [17.2%], and intra-arterial calcium injection, 3 [10.3%]).

A morphological study located insulinoma in all patients except one (n=28, 96.5%), who had an insulinoma associated with MEN 1. Abdominal CT detected 21 cases (71.4%; 95.4% sensitivity). All other cases were discovered by endoscopic ultrasound (n=3), MRI (n=1), PET/CT with 68Ga-DOTA-exendin-4 (n=1), intra-arterial calcium injection (n=1), and intraoperative ultrasonography (n=1). The diagnostic sensitivity of endoscopic ultrasound, intraoperative ultrasonography, and abdominal MRI in our study was 85%, 75%, and 40% respectively. The insulin stimulation test by intra-arterial calcium injection was able to locate one insulinoma at the head of the pancreas. On the other hand, a morphological study using PET/CT with 68Ga-DOTA-exendin-4 showed pathological peripancreatic uptake consistent with ectopic insulinoma.

TreatmentMost patients (n=27, 93.1%) underwent surgery (median time from diagnosis to surgery, four months; interquartile range, 2–7 months). One of the two patients (6.9%) not undergoing surgery had a malignant insulinoma with metastatic liver involvement, and the other refused surgery due to his advanced age. Open surgery was performed in most cases (n=25, 92.6%), while laparoscopic surgery was used in the other patients (n=2, 7.4%). Most patients (n=18, 66.7%) underwent tumor enucleation, while partial pancreatectomy was performed in the rest (n=9, 33.3%). Nine patients (33.3%) experienced surgical complications, of which pancreatic fistula was the most common (n=4, 14.8%). Seventeen patients (58.6%) received medical treatment, mainly diazoxide (n=16, 55.2%), to control hypoglycemia before surgery. A patient with metastatic malignant insulinoma was treated with everolimus. All three patients with insulinoma associated with MEN 1 underwent enucleation of a solitary tumor located in the tail of the pancreas (one patient) or partial pancreatectomy (two patients). Of the latter two patients, one had multiple insulinomas and the other an isolated insulinoma, both of which were located at pancreatic body level. Of these, the first was cured after surgery, while the second experienced several recurrent tumor lesions.

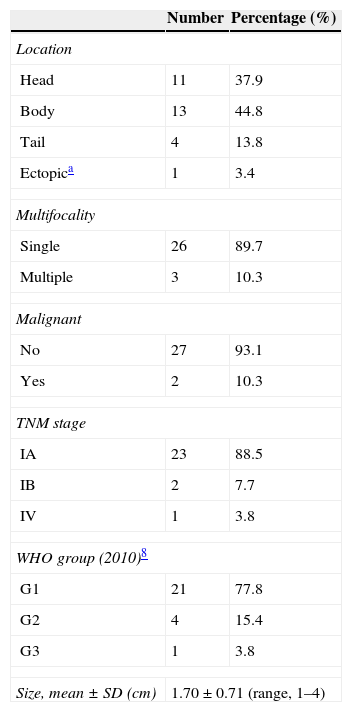

Table 2 shows data related to the tumors. Most patients (n=23, 88.5%) had tumor limited to the pancreas ≤2cm with no nodal involvement or distant metastases (stage IA; T1N0M0), two patients (7.7%) had tumor limited to the pancreas >2cm with no nodal involvement or distant metastases (stage IB; T1N0M0), and one patient (3.8%) had a pancreatic tumor with multiple liver metastases (stage IV; T1N1M1). Most insulinomas were well-differentiated tumors mainly of a low grade of malignancy (G1). This group encompassed 21 patients (77.8%). Four patients (15.4%) had tumors of intermediate malignancy (G2), only one patient (3.8%) had an insulinoma of a high grade of malignancy or a neuroendocrine carcinoma (G3). Immunochemistry was performed in 23 patients (79.3%) and was positive for insulin in 19 (82.6%), for chromogranin A in 7 (30.4%), for synaptophysin in 7 (30.4%), for somatostatin in 6 (26.1%), and for specific neuronal enolase in 5 (21.7%) patients.

Data related to the tumor.

Clinical follow-up was performed in 25 patients (86.2%) for 76.7±86.2 months (median, 53 months; range, 1–378). Surgery achieved cure in a majority of patients (n=24, 88.9%). In three patients (11.1%), one with MEN 1 and multiple insulinomas, another with malignant insulinoma, and the third with occult insulinoma, probably ectopic, all of whom underwent partial pancreatectomy, endogenous hyperinsulinism persisted after initial surgery. Repeat surgery, consisting of corporocaudal subtotal pancreatectomy, liver transplantation, and exploratory laparotomy with no therapeutic intervention, did not control endogenous hyperinsulinism. The patient undergoing liver transplantation was alive at 201 months (16.7 years of follow-up). The second patient with malignant insulinoma, who underwent no surgery and was controlled with combined medical treatment (diazoxide and somatostatin analogs), died at 98 months (8.2 years) of follow-up from hepatic encephalopathy.

On the day of their last visit, the patients were found to have a significant weight decrease (69.1±7.6kg versus 77.1±15.3kg, p=0.041), increased basal plasma blood glucose (p<0.001), and decreased insulin (p=0.004) and C-peptide levels (p=0.011) as compared to the values obtained at diagnosis (Table 1).

DiscussionThis study demonstrates that insulinoma is usually a benign (∼95%), small (1–2cm), and solitary tumor (∼90%) that predominantly affects females (∼80%) aged 45–50 years. Postprandial hypoglycemia occurs in approximately one third of patients, but only a minority has hypoglycemia as the only sign. Enucleation surgery is the procedure of choice, achieving high cure rates (∼90%).

Our study confirms the predilection of insulinoma for females (79.3%), with a female/male ratio of 3.8. This has also been reported in other series, although with a somewhat lower frequency (∼60%).3 Other retrospective Spanish studies have reported incidence rates in females of approximately 60–92%.5,9 The explanation of this finding is not known. A perimenopausal status could be related to the occurrence of insulinoma, because the median age of females in most studies, including ours, ranges from 40 to 50 years.5,9,10 However, the lack of significant differences in age at diagnosis of insulinoma between females and males seen in this and other studies does not support this hypothesis.2

Our series shows that most insulinomas (∼90%) are sporadic tumors, while all others occur in the setting of MEN 1. This last condition was only seen in females, and was always associated with primary hyperparathyroidism that preceded insulinoma, and in one of the three patients diagnosed it was related to multiple insulinomas. In these patients, age at onset was approximately 15 years less than in sporadic cases. Although metastases have been reported in up to 50% of insulinomas associated with MEN 1,11 no case with these characteristics was seen in our series. On the other hand, the only two malignant insulinomas were sporadic, a condition which has been reported in up to 90% of malignant insulinomas.7

The estimated incidence of insulinoma in the American population is four cases per million population and year.2 Its incidence appears to be lower in our population. If all four hospitals studied are considered (overall estimated population covered ∼106) over the 30 years, the number of patients recruited for the reported incidence should have been much higher (∼120 patients). However, the estimated incidence was less than one (0.63 cases per million population and year). This figure is probably underestimated, because some patients could have been seen at other clinical departments such as internal medicine, oncology, and general surgery, instead of being assessed at endocrinology. On the other hand, the incidence of insulinoma doubled in the last 15 years of the study, which is consistent with the increased overall incidence of NETs seen in recent decades.12

Neuroglycopenic symptoms were most commonly associated with hypoglycemia induced by insulinoma in our patient series. Our results also demonstrate that fasting (62.1%) or postprandial (6.9%) hypoglycemia, or both (31%), may occur associated with insulinoma. These percentages are very similar to those reported in the American population (73%, 6%, and 21%, respectively).10

Because of the relatively small size (<2cm) and vascular nature of insulinoma, morphological study with CT in pancreatic and arterial phases may be very helpful for its location.13,14 Dynamic pancreatic MRI with gradient echo sequence may also help in detection.15 Invasive tests include pancreatic endoscopic ultrasonography, which has 89.5% sensitivity and 83.7% accuracy for the detection of insulinoma not located with noninvasive tests. They are especially helpful in insulinoma in the head and body of the pancreas.16 In our series, noninvasive tests, particularly abdominal CT, had a high diagnostic yield, locating virtually three fourths of tumors. Most insulinomas not located with noninvasive tests were discovered with pancreatic endoscopic ultrasound. This test, introduced in recent years, has been shown to be essential for identifying small lesions, and also has the possibility of providing preoperative histological diagnosis. The availability of intraoperative ultrasonography helps in confirming the location of insulinoma and in ruling out the presence of other lesions. Finally, pathological uptake in the PET/CT with 68Ga-DOTA-exendin-4 at peripancreatic level in a patient after two failed surgical procedures confirms the possibility of detecting occult insulinoma with this new diagnostic test, as has been shown in recent studies.17

Despite the recent development of laparoscopic surgery, open surgery was most commonly performed (92.6%). Cure was achieved in the vast majority (∼90%) of patients who underwent an enucleation procedure. As a diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm for insulinoma management, based on information from this study and the main series reported3 it is advisable that, once hypoglycemia associated with endogenous hyperinsulism has been diagnosed and an intake of insulin-secreting oral hypoglycemic drugs has been ruled out, a location study should be started using noninvasive tests, preferably abdominal TC, followed by abdominal MRI. If the results continue to be negative, invasive location tests, preferably endoscopic ultrasonography, should be performed, followed by intra-arterial calcium injection. If the tests are still negative, peripancreatic PET/CT with 68Ga-DOTA-exendin-4 should be considered. If a single tumor is located, enucleation by open surgery (deeply located tumors) or laparoscopic surgery (superficially located tumors) may be considered. If tumors are located deeply and cannot be palpated, intraoperative ultrasonography may be very helpful. Finally, multiple tumors may need subtotal or total pancreatectomy.3

Pancreatic fistula was the main postoperative complication (∼14%), which agrees with the reports in other series.3 Although a recurrence rate up to 7.2% has been reported,3 no patient in our series experienced a recurrence during the follow-up time, but tumor persisted in some cases (11.1%) after initial surgery. Tumor persistence was associated with multiple insulinomas associated with MEN 1, with malignancy, and with no image (occult insulinoma) in preoperative location tests.

Experience with orthotopic liver transplantation after hepatectomy in patients with metastatic malignant insulinoma is relatively scarce. However, transplant may be considered as a treatment option in selected cases, such as patients who are relatively young (<55 years), with refractory hypoglycemia after the failure of medical and surgical treatment, well-differentiated tumors with low cell proliferation indices (Ki 67 <10%), low hepatic tumor burden (<50%), stable disease for at least six months before transplant, and the absence of systemic metastatic dissemination.18–20 Of the two patients with malignant insulinoma metastatic to the liver, one was not a candidate for liver transplant because of age (65 years) and an associated tumor (breast cancer), while the other patient underwent liver transplantation at 51 years. Symptomatic control of the disease was achieved in this patient until 14 years after transplant, despite the occurrence of hepatic and retroperitoneal metastatic recurrence.

The postoperative mortality rate of insulinoma ranges from 3% to 4%, and is usually associated with metastatic malignant disease or postoperative complications related to open surgery (peritonitis and sepsis secondary to pancreatic fistula, intra-abdominal hemorrhage, pancreatitis, and infrahepatic abscess).3 The mortality rate in our study was 3.5%, which corresponded to the death from hepatic encephalopathy of a patient with metastatic malignant insulinoma with liver involvement and a second tumor, which occurred after a long follow-up time (8 years). No patient died after surgery due to complications derived from open surgery.

The strengths of our study include the large patient sample examined as compared to other Spanish series and the long observation period analyzed. The main study limitations are those derived from the retrospective and multicenter nature of the study, which implies a lack of uniformity in diagnostic criteria, imaging resources, and treatment offer (open surgery, laparoscopy) between the different hospitals, as well as an absence of recruitment criteria, which may have affected our calculation of the estimated incidence.

Although insulinoma is a usually solitary, benign, and sporadic tumor in which enucleation surgery achieves cure, it is sometimes associated with diagnostic difficulties that delay location and, thus, definitive curative surgery. It is therefore necessary to introduce, develop, and potentiate insulinoma location techniques, both noninvasive tests, such as PET/CT with 68Ga-DOTA-exendin-4, with high diagnostic yield, and invasive tests such as endoscopic ultrasonography, which also allow for cytological study. On the other hand, in patients with MEN 1-associated or malignant insulinoma, it is essential to provide individualized management by creating multidisciplinary groupings such as endocrine tumor teams, consisting of different specialists who each bring their own particular expertise and experience to the diagnosis, treatment, follow-up, and prevention of these tumors.21

In conclusion, insulinoma is a functioning pancreatic tumor, usually single, small, and benign, which occurs with a low incidence mainly in females in the fifth decade of life. The tumor has an excellent prognosis after surgery once it has been located by pancreatic CT and/or MRI. Invasive tests such as pancreatic endoscopic ultrasonography help discover tumors not located initially with noninvasive tests. Life expectancy appears to be normal in patients cured after surgery. The mortality rate, although low, is not null and is associated with metastatic malignant insulinoma; despite this, however, malignant disease allows for a long survival.

Conflicts of interestThe authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Iglesias P, Lafuente C, Martín Almendra MÁ, López Guzmán A, Castro JC, Díez JJ. Insulinoma: análisis multicéntrico y retrospectivo de la experiencia de 3 décadas (1983-2014). Endocrinol Nutr. 2015;62:306–313.