Adequate nutritional support includes many different aspects, but poor understanding of clinical nutrition by health care professionals often results in an inadequate prescription.

Material and methodsA study was conducted to compare enteral and parenteral nutritional support plans prescribed by specialist and non-specialist physicians.

ResultsNon-specialist physicians recorded anthropometric data from only 13.3% of patients, and none of them performed nutritional assessments. Protein amounts provided by non-specialist physicians were lower than estimated based on ESPEN (10.29g of nitrogen versus 14.62; p<0.001). Differences were not statistically significant in the specialist group (14.88g of nitrogen; p=0.072). Calorie and glutamine provision and laboratory controls prescribed by specialists were significantly closer to those recommended by clinical guidelines.

ConclusionNutritional support prescribed by specialists in endocrinology and nutrition at San Pedro de Alcántara Hospital was closer to clinical practice guideline standards and of higher quality as compared to that prescribed by non-specialists.

Un adecuado plan de soporte nutricional conlleva numerosos aspectos, si bien, la falta de adecuado conocimiento en nutrición clínica de los trabajadores sanitarios en general hace que su prescripción no sea adecuada.

Material y métodosSe realizó un estudio de concordancia comparando soportes nutricionales enterales y parenterales en un mismo individuo con una misma situación de estrés por parte de médicos especialistas en endocrinología y nutrición y médicos no especialistas.

ResultadosLos datos antropométricos fueron registrados en un 13,3% de los pacientes por médicos no especialistas, que no realizaron ningún tipo de valoración del estado nutricional previo al inicio del soporte nutricional. El aporte proteico de médicos no especialistas fue inferior a lo estimado según ESPEN (10,29g de nitrógeno vs 14,62; p<0,001), no así en el caso de médicos especialistas (14,88g de nitrógeno; p=0,072). Los aportes calóricos y de glutamina pautados por especialistas se asemejaron más a lo establecido en las guías de forma estadísticamente significativa, al igual que los controles analíticos realizados.

ConclusiónLos soportes nutricionales pautados por los médicos especialistas en endocrinología y nutrición en el Hospital San Pedro de Alcántara se asemejan más a los estándares de las guías de práctica clínica, y son superiores en cuanto a estándares de calidad y cuidado adecuado de los pacientes respecto a los pautados por los médicos no especialistas.

The planning of adequate nutritional support consists of the following steps: a decision as to whether nutritional support of any kind should be given based on the patient's current status; an assessment of nutritional status including anthropometric and biochemical parameters; an estimation of the requirements of calorie, protein, water and electrolytes, and vitamins and trace elements; an evaluation as to whether the patient may benefit from some nutraceuticals; and the establishment of the most adequate nutritional support plan based on the available access route (oral, enteral, or parenteral). This should be a dynamic process where changes in composition and access route should be assessed based on the clinical and laboratory course of the patient.1,2 However, this support therapy, which has been shown to be very important in the clinical course of the patient,3–6 is not usually taken into account by non-specialist healthcare professionals, mainly because they lack adequate knowledge of clinical nutrition or underestimate the value of the therapy.7 In the current organization of our healthcare system, endocrinology and nutrition is the only clinical specialty where specific training in clinical nutrition is given. Based on this fact, and on conclusions from prior studies suggesting that endocrinologists perform better and faster adjustments in thyroid hormone replacement therapy8 as compared to non-specialist physicians, we will attempt to determine whether nutritional support plans prescribed by specialists in endocrinology and nutrition comply better with the standards and controls proposed by the main clinical practice guidelines.

Materials and methodsOur hypothesis was that nutritional support (NS) prescribed by physicians who have not specialized in endocrinology and nutrition contains a protein provision at least 30% lower than that recommended by clinical practice guidelines. Differences between calorie provisions, the measurement of basic anthropometric parameters, the use of immunonutrients, and laboratory controls of the NS plan performed would also be determined.

Type of studyThis was a concordance study in standard clinical practice.

Sample size estimationIn order to show that the difference in the primary objective given in the hypothesis was true, and assuming a beta error of 10% and 95% confidence, a sample of 22 NS plans per group (specialist and non-specialist physicians) was considered necessary to assess differences in the provisions of macronutrients and nutraceuticals and in anthropometric and biochemical measurements. To increase statistical power, it was decided to increase the sample size to 30 subjects.

Eligible patientsPatients under a similar stress situation who had sequentially received artificial NS for at least five days from a non-specialist physician and for an additional five days from a specialist in endocrinology and nutrition and who had agreed to the use of data collected for this study were considered eligible for the study. Such a situation commonly occurs at the study site, where NS is not only prescribed by the department of endocrinology and nutrition, but may be prescribed by any specialist, and a request for collaboration may be received several days after admission. The following departments participated in the study: general surgery, orthopedic surgery, otolaryngology, gastroenterology, internal medicine, oncology, neurology, vascular surgery, thoracic surgery, plastic surgery, urology, hematology, pneumonology, intensive care unit, traumatology, and nephrology. They are all located at Hospital San Pedro de Alcántara (HSPA) (Cáceres).

ProcedureFrom September 2013 to June 2014, a specialist in endocrinology and nutrition from the HSPA nutrition unit detected all patients eligible for the study by retrospective review of the unit database. Patients in whom artificial NS was based on an oral diet with oral nutritional supplements were excluded because there were no records of oral intake, and calorie and proteins provided by the diet could not therefore be calculated. The following information was subsequently collected:

- 1.

Basic anthropometric data (weight and height) recorded before and after nutritional intervention of the specialist physician in the clinical history or the treatment sheet, and the name of the person who recorded them.

- 2.

Any assessments of nutritional status (percent weight loss, NRS-2002, SNAQ, CONUT, VSG, ASPEN 2012 consensus recommendations) recorded in the clinical history before and after the nutritional intervention of the specialist physician and the names of the professionals who recorded them.

- 3.

The measurement of calories provided by the different NS plans.

- (a)

If NS was based on parenteral nutrition (PN) formulated at the pharmacy, the label identifying the PN formula was taken. It should be noted that there are four standardized PN formulas at HSPA.

- (b)

If a three-chamber PN formula ready for use or a low-calorie peripheral PN (PPN) had been used, calorie provision was taken from the data sheet of the product.

- (c)

Enteral nutrition (EN) formulas available at the study site had a calorie density ranging from 1 to 2kcal/mL. Calorie provision was estimated by multiplying the calorie density of the formula (both EN and PN) by the prescribed volume.

- (d)

The limits of the comparison standard were subsequently increased by 5% because of the existence of protocolized formulas at the pharmacy department which might have resulted in inadequate adjustment of calorie provisions, in order to reduce human error in the preparation of solutions.

- (a)

- 4.

The measurement of proteins provided by the different NS plans.

- (a)

If NS was based on PN formulated at the pharmacy, the label identifying the PN formula, including the existing protocolized formulas, was taken.

- (b)

When a three-chamber PN formula or PPN was prescribed, protein provision was taken from the data sheet of the product.

- (c)

Protein provided by PN was estimated by determining the grams of nitrogen in the prescribed PN volume and multiplying the figure by 6.25 to obtain the grams of protein.

- (d)

Protein provided by EN formulas available at the study site ranged from 16% to 24% of total calorie contents, and protein modules could be added to the formulas to adjust the provisions based on the estimated needs. Protein provided by EN was estimated as the percentage of proteins out of the total calories provided, divided into the Attwater factor for proteins (4kcal/g) to obtain the grams of proteins provided.

- (a)

- 5.

The measurement of the nutraceuticals provided.

- (a)

The amount of parenteral glutamine was measured as the amount provided in the amino acid solution.

- (b)

Parenteral provision of n−3 FA was measured based on the lipid solution used in the PN formula.

- (c)

An EN formula enriched in eicosapentaenoic acid, gamma-linolenic acid, and antioxidants was available, as well as another formula enriched in arginine, nucleotides, antioxidants, and glutamine.

- (a)

- 6.

The following biochemical controls were performed: the biochemical measurements performed during NS by specialist and non-specialist physicians were reviewed, and the cases where triglycerides, liver function tests, phosphorus, magnesium, calcium, prealbumin, and nitrogen balance had been measured at least once weekly were specified.

- 7.

Standards used for comparison.

- (a)

For parenteral NS, the 2009 ESPEN guidelines on PN were used.9 Provisions were calculated based on the anthropometric data recorded in the clinical history.

- (b)

For parenteral glutamine, the 2011 ASPEN consensus statement10 was used. Provisions were calculated based on the anthropometric data recorded in the clinical history.

- (c)

For enteral NS, the 2006 ESPEN guidelines were used.11 Provisions were calculated based on the anthropometric data recorded in the clinical history.

- (d)

For patients with BMI>28kg/m2, weight adjusted to a BMI of 25 was used as an index.

- (e)

For patients with BMI<18.5kg/m2, weight was adjusted to BMI=22.

- (a)

SPSS v.20 for Windows was used for statistical analysis.

A Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess whether or not variables were normally distributed.

Quantitative variables were given as mean and standard deviation if they were normally distributed, and as median and range if not normally distributed. Qualitative variables were given as percentages.

A Student's t test and an ANOVA test for repeated measures were used to compare the means of normally distributed variables. For non-parametric variables, a Wilcoxon test (for quantitative non-normally distributed variables) and a McNemar test (for nominal variables) were used. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

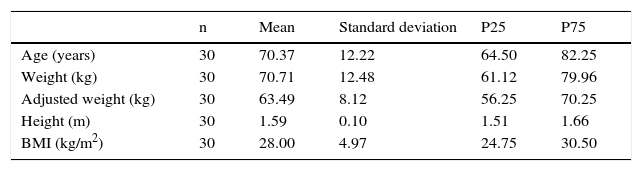

ResultsData were collected from 30 patients (10 males [33.33%] and 20 females [66.66%]) who met the inclusion criteria. Table 1 shows the age and anthropometric characteristics of the patients.

Anthropometric characteristics and age of study population.

| n | Mean | Standard deviation | P25 | P75 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 30 | 70.37 | 12.22 | 64.50 | 82.25 |

| Weight (kg) | 30 | 70.71 | 12.48 | 61.12 | 79.96 |

| Adjusted weight (kg) | 30 | 63.49 | 8.12 | 56.25 | 70.25 |

| Height (m) | 30 | 1.59 | 0.10 | 1.51 | 1.66 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30 | 28.00 | 4.97 | 24.75 | 30.50 |

BMI, body mass index; kg, kilogram; m, meter; n, sample size; P25, 25th percentile; P75, 75th percentile.

Outside the nutrition unit, NS was prescribed by non-specialist physicians at the departments of general surgery (20%), anesthesia and resuscitation (46.7%), intensive care (13.3%), and other departments (20%). In all other cases, the participation of the nutrition unit was requested for NS implementation and monitoring.

Indications for NS included “the impossibility of safe oral intake” (16.7%), “postoperative gastrointestinal rest” (46.7%), “sepsis” (3.3%), “severe mucositis” (10.0%), and “other indications for gastrointestinal res” (23.3%).

A review of anthropometric data (weight and height) in the clinical histories only found weight data for 4 out of 30 patients (13.33%) and height data for 3 out of 30 (10%), while specialist physicians collected these data, either directly or indirectly, in 100% of patients. In addition, while non-specialist physicians did not record any type of nutritional assessment, specialists in endocrinology and nutrition performed nutritional assessment in 100% of patients in their standard practice, rather than in a research context.

Estimated calorie provision according to ESPEN ranged from 1587.14±202.45kcal when calculation was made as weight (kg) (adjusted or not depending on BMI) by 25kcal/kg, to 1904.97±243.54kcal when estimation used 30kcal/kg as a factor. Mean calorie provision by non-specialist physicians was 1425.2±570.74kcal, while provision by specialist physicians was 1846±243.70kcal. An analysis showed that 56.6% (17/30) of NS treatments prescribed by specialist physicians were within the ranges recommended by ESPEN, as compared to only 13.33% (4/30) of NS treatments prescribed by non-specialist physicians (p<0.0001). When both limits of the ranges were widened by 5%, 86.66% (26/30) of NS treatments prescribed by specialists were within the recommended values, as compared to only 26.66% of those prescribed by non-specialists (p<0.001).

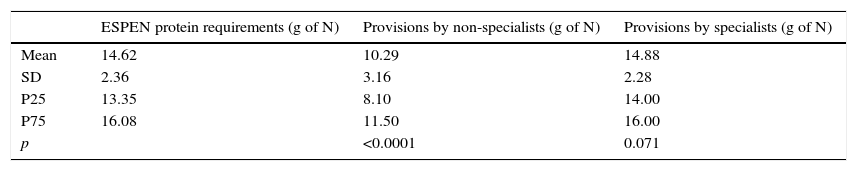

A comparison of protein provisions found no significant differences between provisions recommended by ESPEN and those selected by endocrinologists (p=0.071), while differences were found in provisions prescribed by non-specialists (p=0.0001). Table 2 shows mean provisions, SD, and quartiles.

Comparison of protein provisions versus protein recommendations.

| ESPEN protein requirements (g of N) | Provisions by non-specialists (g of N) | Provisions by specialists (g of N) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 14.62 | 10.29 | 14.88 |

| SD | 2.36 | 3.16 | 2.28 |

| P25 | 13.35 | 8.10 | 14.00 |

| P75 | 16.08 | 11.50 | 16.00 |

| p | <0.0001 | 0.071 |

SD, standard deviation; g, grams; N, nitrogen; P25, 25th percentile; P75, 75th percentile.

As regards the use of immunonutrients, glutamine was only studied because it was the substance for which the most evidence was available at the time of the study. The sample size was reduced to 26 patients (those with PN formulations). Sixteen (61.54%) of these patients had been prescribed glutamine supplementation. Supplementation was recommended by non-specialist physicians in only 3 patients (11.5%; p=0.002), and by specialists in 15 cases (57.69%; p=0.063; κ=0.61).

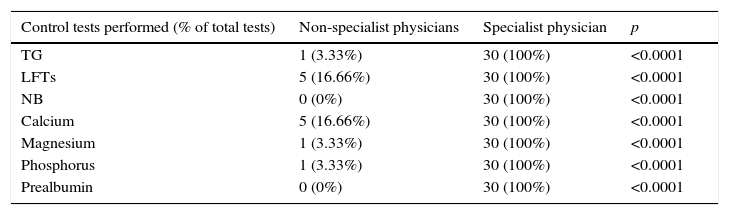

Finally, data from laboratory tests performed during NS (the first 5 days) were collected. The results are shown in Table 3.

Comparison of laboratory control tests performed by specialist and non-specialist physicians.

| Control tests performed (% of total tests) | Non-specialist physicians | Specialist physician | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| TG | 1 (3.33%) | 30 (100%) | <0.0001 |

| LFTs | 5 (16.66%) | 30 (100%) | <0.0001 |

| NB | 0 (0%) | 30 (100%) | <0.0001 |

| Calcium | 5 (16.66%) | 30 (100%) | <0.0001 |

| Magnesium | 1 (3.33%) | 30 (100%) | <0.0001 |

| Phosphorus | 1 (3.33%) | 30 (100%) | <0.0001 |

| Prealbumin | 0 (0%) | 30 (100%) | <0.0001 |

NB, nitrogen balance; LFTs, liver function tests; TG, triglycerides; p, p value.

At the end of the 1990s, two studies provided evidence of the general ignorance of clinical nutrition by healthcare staff. In 1999, Nightingale assessed the degree of knowledge regarding the management of malnutrition by administering a survey of 20 multiple choice questions to 29 physicians, 65 students, 45 nurses, 11 pharmacists, and 11 dietitians. Mean scores obtained were 7, 8, 7, 9, and 16 points respectively.12 In another study13 which collected data from 70 hospitals evaluating 450 nurses and 319 physicians, only 34% of physicians had recorded patient weight in the clinical histories, while the others did not consider it important. Our study is consistent with these findings. Thus, non-specialist physicians prescribe NS at our hospital without previous anthropometric measurements (recorded for only 15% of patients) or assessments of nutritional status (performed in no patients), and NS monitoring (bearing in mind that the complications of NS may be serious and even fatal) is virtually absent. As regards the evaluation of requirements, considerable differences exist between the amounts recommended and provided among specialist physicians (who follow the guidelines issued by scientific bodies to a much greater extent, particularly as regards the provision of proteins and nutraceuticals, in which no statistically significant differences could be shown). As regards calorie provision, the differences between specialist physicians and ESPEN recommendations may be due to the existence of protocols for formulating parenteral nutrition in individual patients, the existing standards being followed in an attempt to reduce formulation errors; in fact, these differences are considerably decreased when the margin of recommendation is slightly widened (an agreement in 85% of cases for specialist physicians). This does not occur however in the group of non-specialist physicians, who calculate widely varying calorie provisions (there was agreement with ESPEN in only 27% of cases using widened margins); this difference may also be due to an inadequate use of formulas consisting of glucose and amino acids, adequate as supplemental PN, as if they were total PN formulas.

The main limitation of our study is small sample size, although there were no additional cases that could have been included in the study during its duration. Potential reasons include, on the one hand, the fact that the nutrition unit would not have been aware of the administration of three-chamber formulas or solutions of amino acids and glucose prescribed by other specialists, as these patients could not be actively detected, and the refusal of departments such as geriatrics to participate in the study. Nevertheless, the differences between the study groups are so wide that they support our theory that a majority of hospital physicians have insufficient knowledge either to prescribe or to adequately monitor NS.

ConclusionsNS prescribed by specialists in endocrinology and nutrition at Hospital San Pedro de Alcántara is similar to standard NS in clinical practice guidelines, and is superior in quality standards and adequate patient care to that prescribed by non-specialist physicians.

Conflicts of interestThe authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Morán López JM, Piedra León M, Enciso Izquierdo FJ, Luengo Pérez LM, Amado Señaris JA. Diferencias en estándares de calidad a la hora de pautar un soporte nutricional: diferencias entre médicos especialistas y no especialistas. Endocrinol Nutr. 2016;63:27–31.