Prevalence of type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is increasing worldwide. Care provided appears to have an influence on the course of disease. The aim of this study was to ascertain the prevalence of T1DM and to collect data on the resources and care used in Asturias.

Material and methodsA descriptive, cross-sectional study including patients born between 2000 and 2014 with diagnosis of T1DM at 31/12/2014. Patients were identified using two independent data sources. Information was collected from medical records. A descriptive data analysis was performed to provide frequency distributions and measures of position and dispersion.

Results146 patients were identified, with a total prevalence of 1.25/1000 children. Prevalence rates by age group were 0.21, 1.15, and 2.40 by 1000 in children aged 0–4, 5–9, and 10–14 years respectively. Autoimmune thyroid disorders and celiac disease were found in 8.2% and 6.8% respectively, while 14.4% had a family history of T1DM and 29.4% of T2DM. Ninety-two children were treated by pediatricians and 34 by endocrinologists. All children were receiving multiple dose insulin treatment and none of them used self-monitoring blood glucose systems. Health education was provided to 37.7% of children.

ConclusionsThis study reports the first data on T1DM prevalence in children under 15 years old in Asturias and provides care data that show the disparity in care received depending on healthcare area.

La prevalencia de diabetes mellitus 1 (DM1) está aumentando en todo el mundo. La atención recibida parece tener influencia en la evolución de la enfermedad. El objetivo es conocer la prevalencia de DM1, así como los recursos y datos asistenciales que se están utilizando en Asturias.

Material y métodosEstudio descriptivo, transversal, siendo la población a estudio los nacidos entre el 2000 y el 2014, con diagnóstico de DM1 a 31/12/2014. Se identificó a los pacientes a través de dos fuentes de datos independientes. La información se recogió a través de las historias clínicas. Se realizó un análisis descriptivo de los datos proporcionando distribuciones de frecuencias y medidas de posición y dispersión.

ResultadosSe identificaron 146 pacientes, la prevalencia total fue de 1,25/1.000 niños. Por grupos de edad fue de 0,21; 1,15 y 2,40 por cada 1.000 en los niños de 0-4; 5-9 y 10-14 años respectivamente. El 8,2% presentaban alteraciones tiroideas autoinmunes y el 6,8% padecían enfermedad celíaca. El 14,4% tenían antecedentes familiares de DM1 y el 29,4% de DM2. Noventa y dos niños eran atendidos por pediatras y 34 por endocrinólogos. El 100% seguía terapia con múltiples dosis de insulina y ninguno utilizaba sistemas de monitorización continua de glucosa. El 37,7% recibió educación para la salud.

ConclusionesEste estudio recoge los primeros datos de prevalencia de DM1 en menores de 15 años en Asturias y aporta datos asistenciales que permiten dar cuenta de la disparidad en cuanto a la atención recibida según área sanitaria.

According to the International Diabetes Federation,1 586,000 children and adolescents under 15 years of age have type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM1) worldwide.

According to the different published studies, the prevalence of DM1 in Spain ranges from 0.95 cases/1000 inhabitants in the recruitment population of Hospital de Mérida2 to 1.7 cases/1000 in Andalusia.3

In Asturias, two epidemiological studies have been carried out on DM1 in patients under 15 years of age. The first of these studies was conducted in 1998 and reported an incidence of 11.5 cases/100,000 inhabitants/year in the period 1991–1995.4 The second study in turn reported an adjusted incidence of 15.6 cases/100,000 inhabitants/year in the period 2002–2011.5 However, until the present study, the prevalence of DM1 in children under 15 years of age in the region of Asturias was not known.

Studies have been carried out in Europe for years not only to determine the epidemiological characteristics of DM1, but also to analyze the resources and particularities of the different healthcare centers that care for these patients. Such aspects appear to have an influence upon patient evolution.6,7 A recent study in the Spanish Autonomous Community of Andalusia has described the situation there with regard to human resources, healthcare data and the use of advanced technology.3

The purpose of the present study was to determine the prevalence of type 1 diabetes mellitus in children under 15 years of age in the region of Asturias, as well as the healthcare resources and data being used. These aspects are essential for detecting the needs of patients and their families, and for the better planning of socio-sanitary care.

Material and methodsA descriptive, cross-sectional observational study was made of the population born between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2014, diagnosed with DM1 as established on 31 December 2014.

The inclusion criteria were: patients under 15 years of age with DM1 and living in Asturias on 31 December 2014.

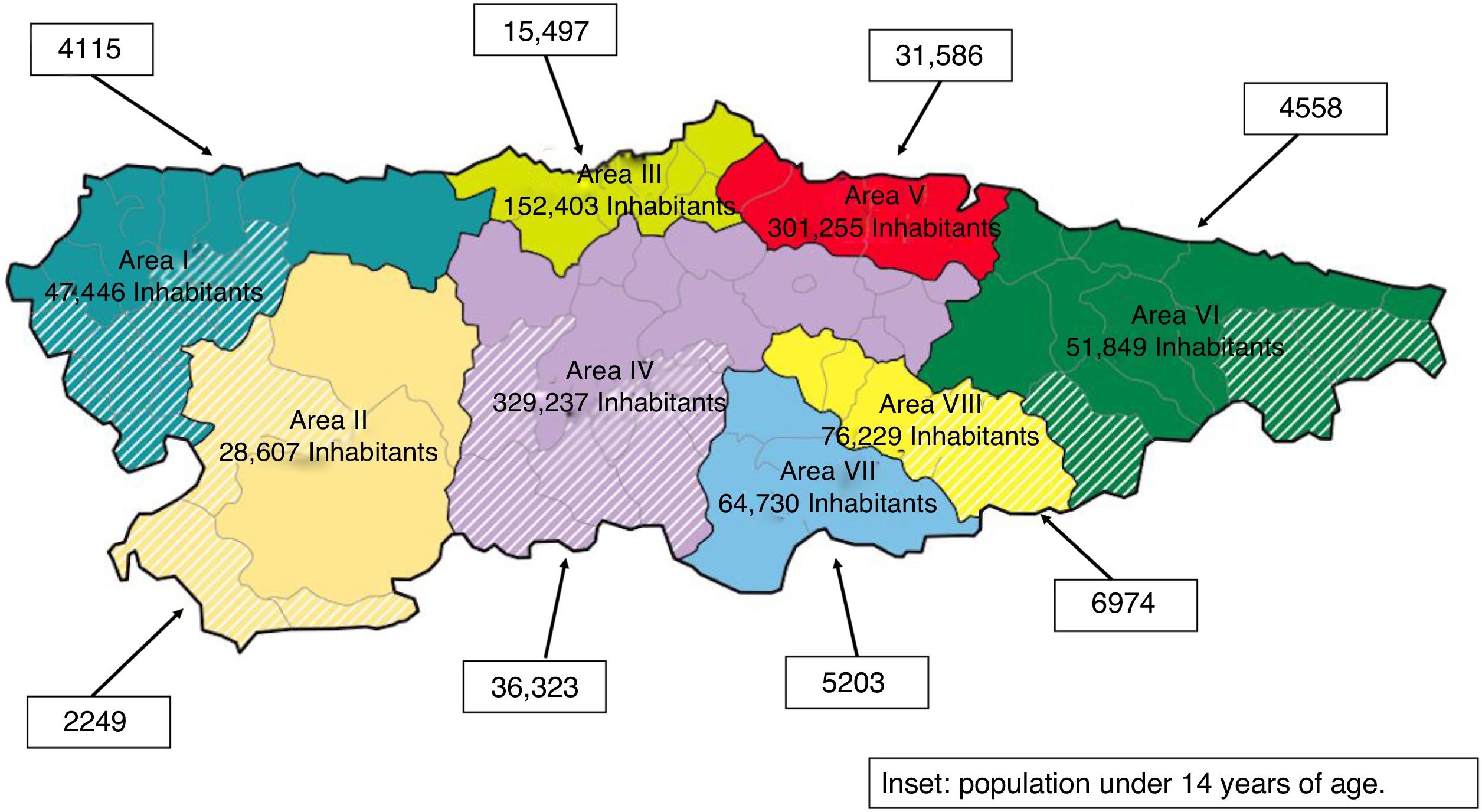

The Asturias Healthcare Map (Mapa Sanitario de Asturias) is territorially structured into 8 administrative areas. In 2014, the population<14 years of age totalled 106,505 (Fig. 1).

In order to optimize patient identification and avoid losses, two independent data sources were used. On the one hand, information was requested from the 8 public hospitals in Asturias through the electronic data services of each of them. On the other hand, the data corresponding to the patients registered in the primary care centers of the 8 healthcare areas were requested through the electronic data services management center of Asturias. The results obtained were then crossed and filtered.

Clinical histories in the region of Asturias are filed in electronic format. The Millennium software application is used at Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, while the Selene application is used at all other hospitals. The OMI_AP program is used at the primary care centers.

Socio-demographic, clinical and healthcare data were obtained from these clinical histories between March and June 2015. A specific form was designed and a database was created for the input of the collected information.

The variables collected included gender, age, age at diagnosis, date of birth and of diagnosis, autoimmune diseases, any family history of DM1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2), human resources (physician and diabetes education nurse), the use of advanced therapies (continuous glucose monitoring systems [CGMS] and continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion [CSII]), and healthcare data (the healthcare area where treatment was received, the frequency of controls, health education interventions and the number of admissions).

With regard to the personal history of DM1 and DM2, we considered first-degree relatives (parents), second-degree relatives (grandparents and siblings), and third-degree relatives (great-grandparents and uncles/aunts).

Prevalence rates were calculated using data from the Spanish National Statistics Institute (Instituto Nacional de Estadística [INE]) referring to Asturias.

A descriptive analysis was made, with frequency distributions for qualitative variables and the mean or median, and dispersion measures such as the standard deviation (SD), for quantitative variables. The analysis was performed using the R statistical package (version 3.3.1).

Ethical and legal issuesAuthorization to carry out the study was requested from the Regional Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Asturias, and from the manager of the Health Service of Asturias and managers of each of the 8 healthcare areas. Likewise, the research project was reported to the child administration authorities of Asturias.

The confidentiality and anonymity of the data used were ensured following the provisions of Organic Act 15/1999 on Personal Data Protection and Spanish Royal Decree 1720/2007.

ResultsA total of 146 children under 15 years of age were found to have DM1 on 31 December 2014. Of these, 49.3% were girls (n=72).

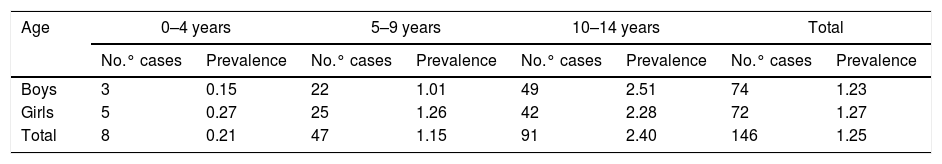

The global prevalence was 1.25 cases/1000 children, and by age groups 0.21, 1.15 and 2.40 cases/1000 children in the age intervals 0–4, 5–9 and 10–14 years, respectively. The gender distribution was 1.23 cases/1000 in boys and 1.27 cases/1000 in girls (Table 1).

Prevalence of type 1 diabetes mellitus according to age and gender groups.

| Age | 0–4 years | 5–9 years | 10–14 years | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.° cases | Prevalence | No.° cases | Prevalence | No.° cases | Prevalence | No.° cases | Prevalence | |

| Boys | 3 | 0.15 | 22 | 1.01 | 49 | 2.51 | 74 | 1.23 |

| Girls | 5 | 0.27 | 25 | 1.26 | 42 | 2.28 | 72 | 1.27 |

| Total | 8 | 0.21 | 47 | 1.15 | 91 | 2.40 | 146 | 1.25 |

The mean age of the children with DM1 was 10.51 years (95%CI=9.99–11.02), with SD=3.14 and a median of 10.8 years. The mean age at the time of diagnosis was 6.58 years (95%CI=5.99–7.16), with SD=3.44 and a median of 6.52 years.

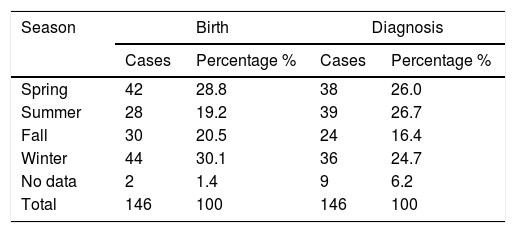

There were no statistically significant differences between the overall birth distribution in Asturias (2000–2014) and the birth distribution of children diagnosed with DM1 (X2=6.4595; df=3; p=0.09127). Likewise, no differences were observed between the distribution of the month of diagnosis and the distribution of births in Asturias (X2=4.191; df=3; p=0.2416). The seasonal distributions of birth and of diagnosis are shown in Table 2.

With regard to associated autoimmune diseases, autoimmune thyroid disease was recorded in 8.2% (n=12), of which 58.3% (n=7) were girls, while celiac disease was recorded in 6.8% (n=10), of which 70% (n=7) were girls. In relation to other diseases, 8.2% (n=12) had asthma and 13.0% (n=19) suffered other conditions.

A total of 14.4% (n=21) had one or more relatives with DM1 (4.1% first degree, 2.0% second degree and 8.2% third degree). Furthermore, 29.4% (n=43) had a family history of DM2 (2.0% first degree, 21.9% second degree and 5.5% third degree).

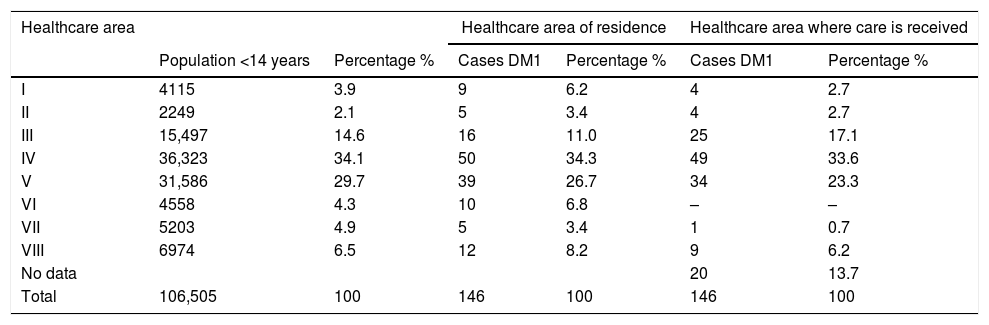

The distribution of the areas of residence and of the areas where specialized care is provided in relation to the different healthcare areas is shown in Table 3.

Distribution of areas of residence and areas where treatment is received in specialized care.

| Healthcare area | Healthcare area of residence | Healthcare area where care is received | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population <14 years | Percentage % | Cases DM1 | Percentage % | Cases DM1 | Percentage % | |

| I | 4115 | 3.9 | 9 | 6.2 | 4 | 2.7 |

| II | 2249 | 2.1 | 5 | 3.4 | 4 | 2.7 |

| III | 15,497 | 14.6 | 16 | 11.0 | 25 | 17.1 |

| IV | 36,323 | 34.1 | 50 | 34.3 | 49 | 33.6 |

| V | 31,586 | 29.7 | 39 | 26.7 | 34 | 23.3 |

| VI | 4558 | 4.3 | 10 | 6.8 | – | – |

| VII | 5203 | 4.9 | 5 | 3.4 | 1 | 0.7 |

| VIII | 6974 | 6.5 | 12 | 8.2 | 9 | 6.2 |

| No data | 20 | 13.7 | ||||

| Total | 106,505 | 100 | 146 | 100 | 146 | 100 |

The human resources involved in the specialized care of diabetic children were a pediatrician and a nurse in each of the following healthcare areas: I, II, VI, VII and VIII. Healthcare area III had two pediatricians and two diabetes education nurses. In healthcare area IV there were two pediatricians and two nurses, while in healthcare area V there were 6 endocrinologists and three diabetes education nurses.

With regard to the controls in specialized care, of the 146 children, 92 were controlled by the pediatrician and 34 by the endocrinologist. In 20 cases the corresponding data could not be obtained. In healthcare area V, the children were seen by specialists in endocrinology and nutrition. The data regarding the frequency of these controls was only available in 7 cases, with a mean of once every 1.86 months, SD=0.69, and a median of 2 months.

All of the children received multiple dose insulin therapy (MDI). None of the medical records contained information regarding the use of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion systems or continuous glucose monitoring systems.

In 37.7% of the cases (n=55) the clinical history explicitly reported that health education interventions had been made: 51 of them in specialized care, two in primary care, and two in both healthcare settings. The type of intervention was specified in 17 cases: diabetes education in 16 cases, and diabetes education added to the visit of healthcare professionals to the school in one case. In the remaining cases, intervention was confirmed, but no further details were provided.

With regard to the number of admissions, data were available on 83 patients who experienced one or more admissions, including that corresponding to diabetes onset. The mean number of admission was 1.5, with a SD=0.98, and a median of one admission. Of the 83 patients who were admitted to hospital, the duration of admission was known in 29 cases, with a mean of 8.83 days, SD=5.04, and a median of 9 days.

DiscussionThe present study recorded a prevalence of 1.25 cases/1000 children under 15 years of age, which is consistent with the average reported by studies conducted in other Spanish regions, the highest prevalence corresponding to Andalusia with 1.7 cases/1000 in a study conducted in 2013,3 while the lowest was recorded in a Mérida healthcare area, with 0.95 cases/1000, in a study carried out in 2008.2 In Castilla y León the prevalence of DM1 was 1.18 cases/1000 children in 2004.8 This prevalence is similar to that recorded in Aragón in 2010, with 1.1 cases/1000,9 a figure that increased to 1.22 cases/1000 in 2013.10 These prevalences are slightly lower than those reported in Castilla – La Mancha in 2008, with 1.44 cases/1000,11 and in Cantabria, where the mean prevalence between 1990 and 1996 was 1.53 cases/1000 children.12

As in other published studies,8,11 the greatest prevalence corresponded to the 10–14 years of age group. A greater total prevalence was seen in girls, except in the 10–14 year interval where males predominated. This is consistent with the results of the study conducted by Giralt et al.,11 where males predominated in all the groups.

Few prevalence studies are available, and moreover their designs are heterogeneous. The latest report from the International Diabetes Federation1 indicates that the incidence of DM1 in children under 15 years of age is growing in many countries, with an overall annual increase of approximately 3%, which implies an increased prevalence of the disease.

There are no official registries of DM1 in the region of Asturias. The creation of such registries is a prerequisite for understanding the epidemiology and for facilitating the better planning of socio-sanitary and educational resource utilization.

The children with DM1 were more often born in winter and spring, unlike in Aragon13 where the greatest number of births occurred in summer and the lowest in winter.

In contrast to what is found in the literature,13–15 we recorded more diagnoses in the summer and spring seasons than in winter and fall. The results of our study are similar to those obtained in Castilla y León in 2003–2004, where most of the cases were diagnosed in summer.16 In a recent study in Vizcaya,17 no differences were observed in the diagnosis of the disease between the four seasons.

As has already been done in Aragón,13 it might be worth exploring the possible relationships between climatology and the history of infectious diseases to see if some link can be established.

In our study, autoimmune thyroid disease was the most prevalent autoimmune disorder associated with DM1, as has also been reported in the literature.18 There is an increased risk of thyroid alterations in people with DM1, where the prevalence of thyroid disease is 10–22%.19 In our study the prevalence was slightly lower (8.2%). According to the literature, female gender appears to be a risk factor in this regard.19 In our study 58.3% of the patients with thyroid alterations were girls.

Craig et al.,20 in a study conducted on three continents, found the prevalence of celiac disease to be approximately 3.5% in children with diabetes, and this figure appears to be greater in females than in males. The observed prevalence of 6.8% is closer to that reported by Marqués Valls et al.21 in Hospital Universitario Sant Joan de Déu (6.4%) or by Maltoni et al.22 in a more recent study in northern Italy (9.8%).

Only 6.1% of the children had a family history of DM1 in first or second degree relatives. This percentage is lower than that reported in the literature, where approximately 15–20% of all people with DM1 were seen to have relatives with the disease. In Cantabria,23 15.5% had a history of DM1, versus 19.5% in Aragón10 and 26% in a study conducted in Castilla y León.16 A study conducted in the Valme hospital recruitment area24 reported a much higher figure (43.5%). No explanation for these differences can be found, based on the data obtained.

In our study, 4.1% of the children had a history of first-degree relatives with DM1, which differs from the 10 to 15% reported worldwide but comes close to the 5% reported in the study conducted in Castilla y León16 and the 6.4% reported in Galicia.25

In turn, 23.9% of the children had a history of first- or second-degree relatives with DM2, which coincides with the data published for Castilla y León (23.9%).16 In Aragón10 the figure was significantly higher (35.3%), but still far from that reported by the Valme hospital recruitment area (65.3%).24 In our study, 2% of the first-degree relatives had DM2, this being similar to the 1.8% found in Galicia. These data could be explained by the high prevalence of DM2 in Spain, and by the fact that the disease is more frequent among elderly people.

It should be noted that migration from one specialized care center to another does not follow the logical flow toward the reference center of the Autonomous Community in healthcare area IV. Such migration could be explained by the type of care provided or by the link established between the parents and the healthcare professionals. In healthcare area V the patients are seen by endocrinologists, while in all the other healthcare areas pediatricians are in charge of patient control. According to the Spanish Society of Pediatric Endocrinology, accredited reference centers are required to offer the best care for children and adolescents, with pediatric health professionals specifically trained in this field.26 At the time this study was carried out, only healthcare area III in Asturias had a pediatric endocrinology unit. The hospitals in the least populated healthcare areas see only a very small number of patients. Following the current recommendations, it might be advisable for these patients to be seen in accredited reference centers in order to ensure the best care possible.

Data regarding the frequency of the control visits could only be obtained in 7 cases. It would be necessary to collect this information using other tools, such as appointment coordination, in order to know the data of the entire population and see whether all the healthcare areas were behaving in the same way.

A number of authors have found CSII systems to be effective and safe in children because they allow good metabolic control to be achieved without an increase in adverse effects.27 These systems also afford advantages over multiple dosing, such as optimal control, reduce severe hypoglycemic events, and are cost-effective.28 However, despite all these advantages, no children in our study were recorded to have benefited from this treatment modality during the study period. The first child to start treatment with a CSII system did so in January 2015 in healthcare area V. The analysis of the SWEET registry showed that of 16,570 patients under 18 years of age, 44.4% used CSII systems.29 A recent study in Andalusia yielded a figure of 5.5%.3

Continuous glucose monitoring systems (CGMS) offer demonstrated benefits in terms of glycemic control not only in patients treated with CSII, but also in patients receiving multiple dose insulin therapy (MDI), and their use in children is recommended.28 However, we found no data in the clinical histories referring to CGMS use as established on 31 December 2014. This may have been due to deficiencies in the registries, or possibly because up until that date their use in children was still very limited due to a lack of knowledge of these systems, self-financing requirements, or other undetermined circumstances.

Structured educational programs adapted to the age and development stage of the patients, with due consideration of the family and social environment, are a useful tool for improving the management of the disease.30 However, fewer than 50% of the clinical histories stated that educational measures had been adopted. Furthermore, the concrete measures taken were not specified, and no evaluation of their effects was indicated. It seems clear that at least at the onset of the disease, all families should receive some type of diabetes education, and here again the registries showed deficiencies despite their importance as tools for conducting follow-up and ensuring the continuity of patient care. The clinical histories have a poor record of the interventions performed by nurses, while interaction with the school environment is rarely taken into consideration.

With regard to the number of admissions, including those corresponding to disease onset, we recorded an average of 1.52 admissions per patient, but this information could only be obtained in 83 cases. It is surprising that not all the clinical histories reported admissions, because all patients are admitted for care, at least at the start of the disease. The data recorded therefore might not adequately reflect the true situation, and this could be explained by deficiencies in the transfer of the data contained in the old case histories in paper format to the new electronic systems.

A possible limitation of this study concerns precision in the compilation of each variable. The electronic clinical history system has only recently been introduced in Asturias. In addition, each healthcare area has digitized and entered the data of the old case histories in paper format to the current electronic databases in a different way. Furthermore, the software application of the reference hospital in the Autonomous Community differs from that used in the other hospitals in the region.

In conclusion, our study reports the first data on the prevalence of DM1 in children under 15 years of age in the region of Asturias. It also offers information on human resources and healthcare data that illustrates the disparity in terms of the care received in the different healthcare areas of the region, as well as the lack of use of advanced therapies.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank Tania Iglesias (statistics consultancy of the University of Oviedo) and Marta Osorio (collaboration in the translation). Likewise, thanks are due to Dr. Isolina Riaño for her generosity and disinterested collaboration in reviewing the manuscript.

Please cite this article as: Osorio Álvarez S, Riestra Rodríguez MR, López Sánchez R, Alonso Pérez F, Oltra Rodríguez E. Prevalencia y datos asistenciales de la diabetes mellitus tipo 1 en menores de 15 años en Asturias. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2019;66:188–194.

This article was previously submitted as an Oral Communication: “Epidemiology of childhood diabetes in Asturias” at the IV International Congress and X National Congress of the Community Nursing Association (Asociación de Enfermería Comunitaria [AEC]), Burgos, 5–7 October 2016.