Pituitary adenomas (PA) are the most common sellar tumours and the most common cause of pituitary disorders.1 However, a wide variety of non-adenomatous tumours, metastases, or cystic, infectious vascular or inflammatory lesions can affect the sellar region.2

Sarcomas are a heterogeneous group of malignant tumours deriving from mesenchymal cells that grow from skeletal and extra-skeletal connective tissue.3 They are divided into two broad groups: soft tissue sarcomas (STSs) and bone sarcomas (BSs).3 They have a prevalence of four to five cases (STS) and one case (BS) for every 100,000 inhabitants and account for 1% of malignant tumours in adults and 12% in children.4 These tumours can appear in any part of the body, and both STSs (angiosarcoma, liposarcoma, fibrosarcoma, undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma) and BSs (Ewing’s sarcoma, chondrosarcoma, osteosarcoma) have been reported affecting the sellar region.5

We present the case of a man who, in 1993, at the age of 42 years, was diagnosed with an incidental sellar mass in a computed tomography performed due to cranioencephalic trauma. He did not have signs or symptoms of hormonal dysfunction. The baseline pituitary study, 24-h urinary free cortisol and ACTH-cortisol test (Synacthen 250 μg) were normal. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pituitary gland showed a sellar lesion with suprasellar extension and infiltration of both cavernous sinuses. Campimetry revealed bitemporal hemianopsia, so a bifrontal craniotomy was performed with subtotal resection of the tumour. The histological study revealed a 30 × 40 mm tumour with immunoreaction to ACTH, cytokeratin AE1/AE3, negative for other pituitary hormones, with Ki-67 < 2%, consistent with silent corticotroph adenoma. The post-surgical study revealed hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and secondary hypothyroidism, and hormone replacement therapy was initiated. The patient was operated on again due to growth of the tumour in 1995 and 1998. The tumour tissue excised on both occasions had a similar histological pattern with immunoreaction to ACTH. Subsequently, the patient received fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy (52 Gy). One year later, pituitary MRI revealed a cystic residual tumour with a maximum diameter of 3 cm. In periodic follow-ups, the patient remained clinically and radiologically stable for 20 years.

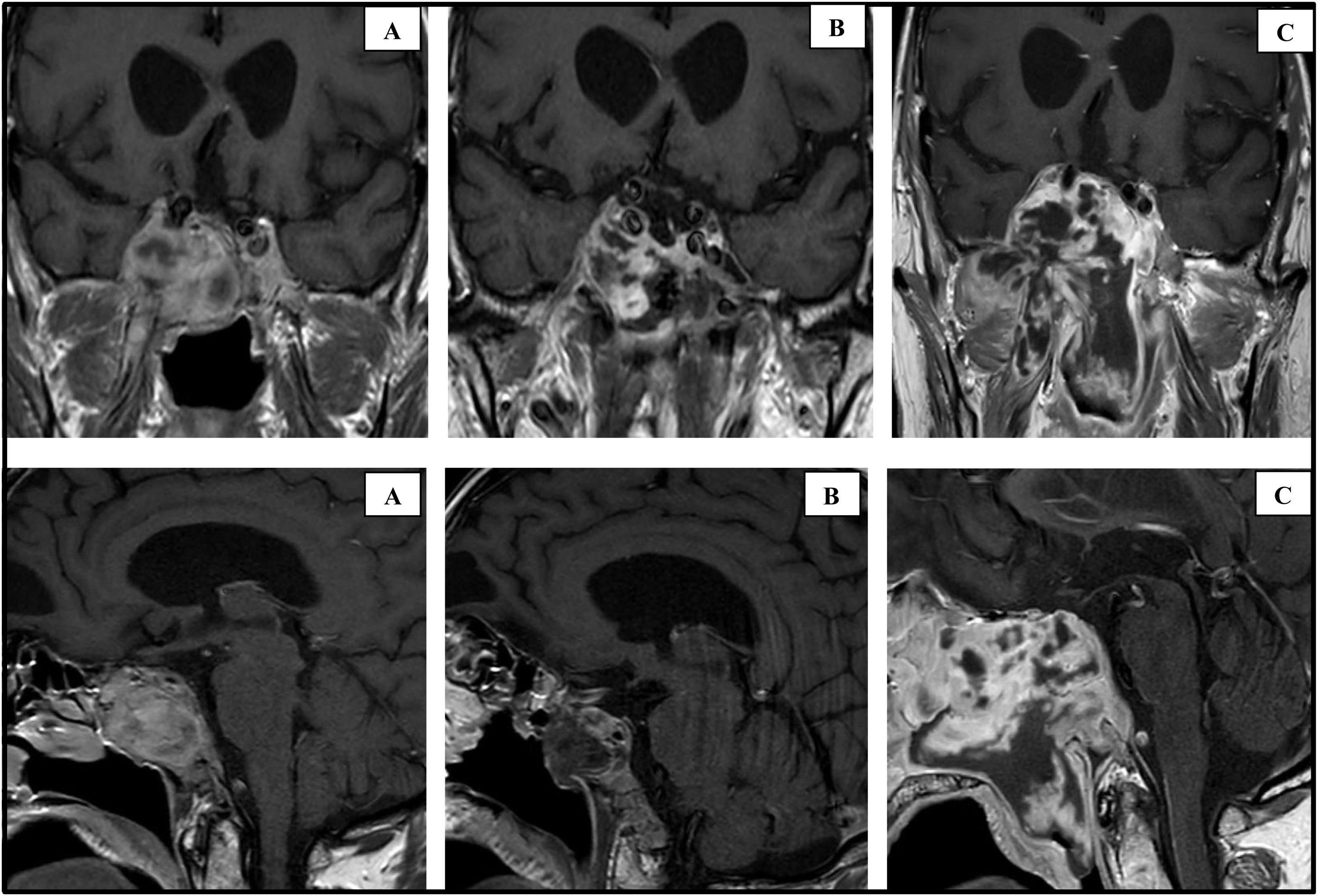

In October 2019, at 69 years of age, the patient was seen for headache, visual disturbance and vomiting that had begun three weeks earlier. The physical examination revealed paralysis of the left sixth cranial nerve. The hormone study found serum GH 0.02 μg/l (0–3.5); IGF-1 3.6 nmol/l (6.2–24.9); TSH < 0.01 mIU/l (0.57–5.51); FT4 15.8 pmol/l (12–22); prolactin 103 mIU/l (98–456); FSH 1.4 IU/l (1.5–12.4); LH < 1 IU/l (1.7–8.6); testosterone 8.4 nmol/l (6.7–25.7); free testosterone 75 pmol/l (>220); urinary free cortisol 540 nmol/day (86–631); plasma ACTH 1.9 pmol/l (2–12); serum cortisol 284 nmol/l (172–497) rising after stimulation (Synacthen 250 μg) to 710 nmol/l. The pituitary MRI showed growth of the residual lesion (Fig. 1A). The tumour was partially resected by transsphenoidal surgery and histological study revealed diffuse positive immunoreaction to vimentin, focal to actin, cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and negative to desmin, CD34 and S100. The histological diagnosis was spindle cell sarcoma with areas of fibroblast and chondroblast proliferation. The MRI at one week after the surgery revealed a reduction in the size of the lesion (Fig. 1B) and the patient was discharged without immediate complications. However, eight weeks later he was seen again for headache and visual disturbance. Considerable growth of the tumour was visible on the pituitary MRI (Fig. 1C), so the patient was referred to Oncology, where he started palliative chemotherapy with doxorubicin, gemcitabine and dacarbazine. In spite of this, he died seven months after the diagnosis of sarcoma.

Coronal and sagittal slices of the pituitary MRI with gadolinium at different timepoints in the disease.

(A) MRI performed in October 2019 showing a mass of 38 × 43 × 30 mm with infiltration of the sellar floor, clivus, occipital bone, compression of the chiasm, right optic nerve and both cavernous sinuses. (B) MRI performed one week after the last surgery (November 2019), showing a reduction in size to 15 × 13 × 23 mm. (C) MRI performed two months after the last surgery (January 2020), showing tumour progression to 66 × 74 × 66 mm.

The incidence of sellar sarcomas is unknown and fewer than 100 cases have been reported to date.5 One aetiological study of 1367 patients with sellar/parasellar masses on MRI found three sarcomas, or 0.2%.6 These tumours are detected in patients with a mean age of 40 years, with a slight predominance in men.5 Although the proportion of radiation-induced sarcomas is lower with current techniques,7 a history of radiation is present in 3–6% of sarcomas, rising to 32% in sarcomas affecting the sellar region.5 The mean time between radiotherapy and tumour appearance is 10 years, although the range is very variable (3–39 years).5 Sellar STSs are more frequently associated with radiotherapy than BSs, the most common subtypes being fibrosarcoma and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma.5 In this regard, our patient’s histological study revealed a sarcoma with vary little differentiation, with a combination of fibroblast (STS) and chondroblast (BS) proliferation, which is uncommon.

The cause of sarcomas is unknown, but the aetiologically strongest environmental factor is radiotherapy.8 The development of these tumours may be influenced by high doses of radiation, exposure at an early age and concomitant use of certain chemotherapeutic agents.8 Some cases have been found in the context of hereditary diseases such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome, neurofibromatosis type 1, McCune-Albright syndrome or diseases of uncertain origin, such as multiple enchondromatosis.5,8 They have also been linked to viruses such as human herpes virus 8, Epstein-Barr virus or HIV, with the latter two reported in patients with sellar region sarcomas.5,8

Sellar sarcomas are voluminous tumours (>3 cm) that present with symptoms of space occupation.5 There are no clinical, analytical or radiological data that lead to their being suspected, so they are confused with non-functioning PAs or other non-adenomatous tumours.5 In our case, we considered that the change in behaviour of the residual tumour could be related to the aggressiveness that some silent corticotroph adenomas can have. Nevertheless, the long period of prior stability and history of radiotherapy led us to a sarcomatous transformation as the most probable cause. Full surgical resection is the only curative option, but this is achieved in less than 20% of cases.4,5 Radiotherapy and chemotherapy have been used as palliative options in progressively growing tumours or advanced metastatic disease,4,5 however, the mean survival of these patients is six months.5

To conclude, sellar sarcomas are uncommon and aggressive tumours with a poor prognosis that appear in middle-aged patients. There is very little to base a presumed diagnosis on prior to surgery, but a change in clinical and radiological behaviour of a previously irradiated residual tumour could be useful in some cases. Full excision is the only option for survival for these patients.

FundingThis study has not received any type of funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Guerrero-Pérez F, Vidal N, Sánchez-Fernández JJ, Vilarrasa N, Villabona C. Transformación sarcomatosa de un corticotropinoma silente después de radioterapia. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2022;69:230–232.