Artificial nutrition (AI) is one of the most representative examples of coordinated therapeutic programs, and therefore requires adequate development and organization. The first clinical nutrition units (CNUs) emerged in the public hospitals of the Spanish National Health System (NHS) in the 80s and have gradually been incorporated into the departments of endocrinology and nutrition (DENs). The purpose of our article is to report on the results found in the RECALSEEN study as regards the professional and organizational aspects relating to CNUs and their structure and operation.

Materials and methodsData were collected from the RECALSEEN study, a cross-sectional, descriptive study of the DENs in the Spanish NHS in 2016. The survey was compiled from March to September 2017. Qualitative variables were reported as frequency distributions (number of cases and percentages), and quantitative variables as the mean, median, and standard deviation (SD).

ResultsA total of 88 (70%) DENs, out of a total of 125 general acute hospitals of the NHS with 200 or more installed beds, completed the survey. CNUs were available in 83% of DENs (98% in hospitals with 500 or more beds). As a median, DENs had one nurse dedicated to nutrition (35% did not have this resource). Fifty-three percent of DENs with nutrition units had dieticians integrated into the unit (median: 1).

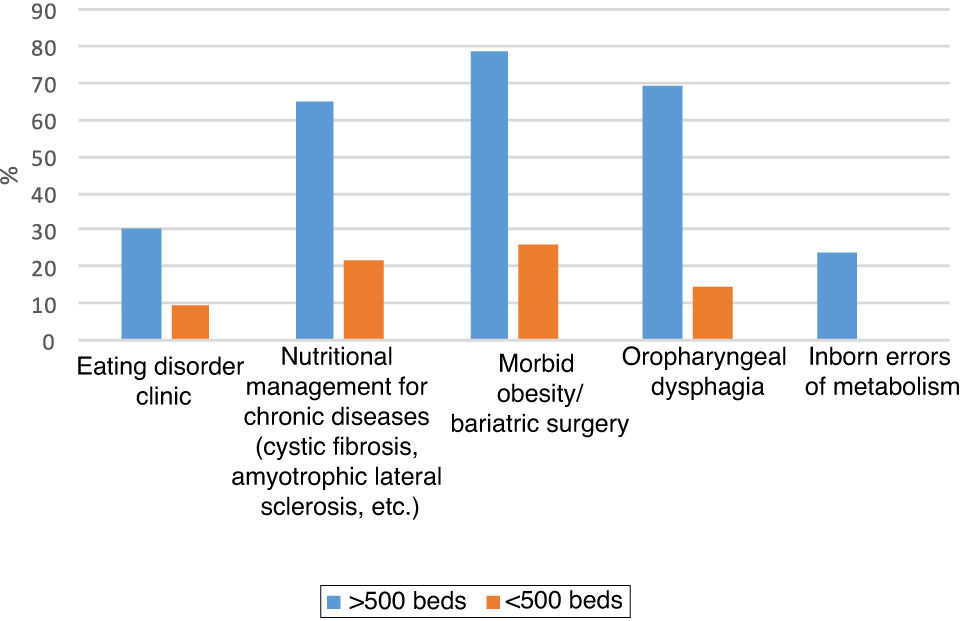

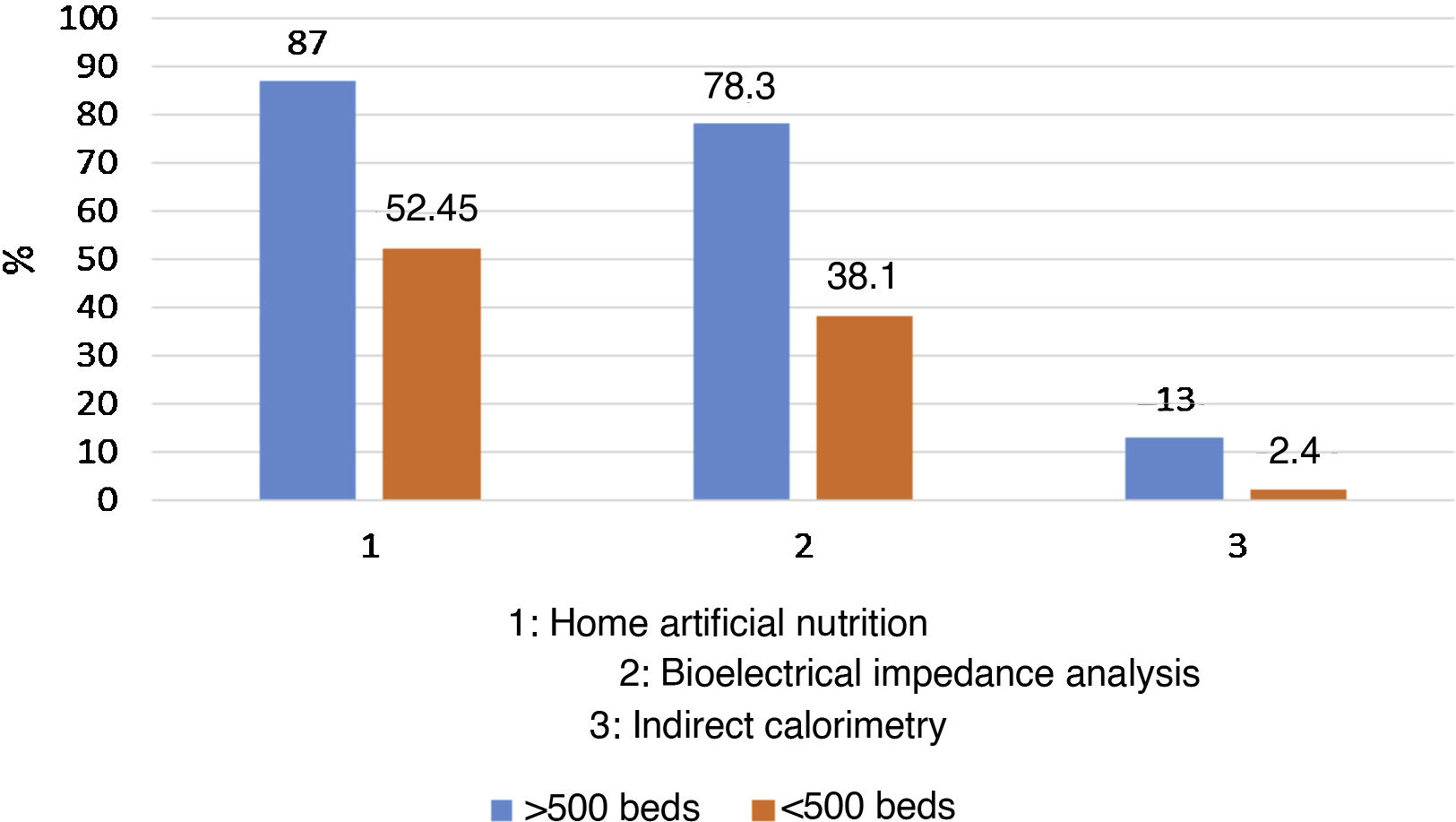

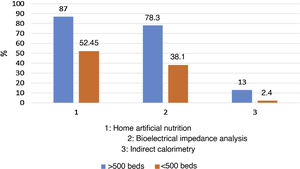

DENs located in hospitals with 500 or more beds are more complex and have a wide portfolio of monographic unit services (morbid obesity, 78.3%; artificial home nutrition, 87%; chronic diseases, 65.2%) and specific techniques (impedanciometry, 78%). However, only 14% of the centers perform universal screening tests for malnutrition, and a secondary diagnosis of malnutrition only appears in 12.3 reports per 1000 hospital discharges.

DiscussionAfter the 1997 and 2003 studies, the results of 2017 show a marked growth and consolidation of CNUs within the DENs in most hospitals. Today, the growth of this specialty is largely due to the care demand created by hospital clinical nutrition. CNUs still have an insufficient nursing staff and dietitians/nutritionists, and in the latter case, atypical contracts or grants funded by research projects or the pharmaceutical industry are common. Units for specific nutritional diseases and participation in multidisciplinary groups, quite heterogeneous, are concentrated in hospitals with 500 or more beds and represent an excellent opportunity for CNU development.

ConclusionsMany DENs of Spanish hospitals include CNUs where care is provided by endocrinologists, who devote most of their time to clinical nutrition in more than half of the hospitals. This is most common in large centers with a high workload in relation to staffing. There is considerable heterogeneity between hospitals in terms of both the number and type of activity of the CNUs.

La nutrición artificial (NA) es uno de los ejemplos más representativos de programas terapéuticos coordinados, lo que hace necesario su desarrollo y adecuada organización. Las primeras Unidades de Nutrición Clínica (UNC) surgen en los hospitales públicos del Sistema Nacional de Salud (SNS) en la década de 1980–1990 y se han ido incorporando progresivamente a los Servicios de Endocrinología y Nutrición (SªEyN). El objeto de nuestro artículo es exponer los resultados obtenidos del estudio RECALSEEN sobre los aspectos profesionales y organizativos relacionados con las UNC, su estructura y funcionamiento.

Material y métodosLos datos se han obtenido del estudio RECALSEEN, que es un descriptivo transversal entre los SºEyN del SNS español referido a 2016. La encuesta se recogió de marzo a septiembre de 2017. Las variables cualitativas se describen con su distribución de frecuencias (número de casos y porcentajes) y las variables de cuantitativas con la media, mediana y desviación estándar.

ResultadosSe han obtenido 88 (70%) respuestas de SºEyN sobre un total de 125 hospitales generales de agudos del SNS con igual o más de 200 camas instaladas. El 83% de Sº EyN incorporaban una UNC (98% en los hospitales de 500 o más camas). Como mediana, los Sº EyN tienen 1 enfermera dedicada a Nutrición (35% no disponían de este recurso). El 53% de Sº EyN con Unidad de Nutrición tenían dietistas integrados en la unidad (mediana: 1).

Los Sº EyN situadas en hospitales de 500 o más camas tienen una mayor complejidad con una amplia cartera de servicios de unidades monográficas (obesidad mórbida —78,3%—, nutrición artificial domiciliaria —87%—, enfermedades crónicas —65,2%—) y de técnicas específicas (impedanciometría —78%—). Sin embargo, sólo se realiza un test de cribado universal de desnutrición en el 14% de los centros y, el diagnóstico secundario de desnutrición, únicamente aparece en 12,3 informes por cada 1.000 altas hospitalarias.

DiscusiónTras los estudios de 1997 y 2003, los resultados de 2017 arrojan un notable crecimiento y consolidación de las UNC dentro de los SºEyN de la mayoría de los hospitales. Actualmente, el crecimiento de la especialidad pasa en buena medida por la demanda asistencial que crea la Nutrición Clínica hospitalaria. La dotación de personal de enfermería y de dietistas-nutricionistas en las UNC sigue siendo insuficiente y, en este último caso, son frecuentes los contratos atípicos, o becas financiadas por proyectos de investigación o por la industria farmacéutica. La presencia de unidades para patologías nutricionales específicas y la participación en grupos multidisciplinares, bastante heterogénea, se concentra en hospitales de 500 o más camas y constituye una excelente oportunidad de desarrollo para las UNC.

ConclusionesLa incorporación de UNC en los S◦EyN es amplia en los hospitales de España, y la asistencia se realiza por endocrinólogos que dedican la mayor parte de su tiempo a la nutrición clínica en más de la mitad de los hospitales. Esta circunstancia es más común en centros grandes, con elevadas cargas de trabajo en relación con las dotaciones de personal. Se observa una considerable heterogeneidad entre los hospitales, tanto en términos de número como de tipo de actividad de las UNC.

The Recursos y Calidad en Endocrinología y Nutrición [Resources and Quality in Endocrinology and Nutrition] (RECALSEEN) registry on patient care in endocrinology and nutrition units of the Spanish National Health System (SNS) was published in 2019. RECALSEEN is a project of the Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición [Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition] with the collaboration of Fundación Instituto para la Mejora de la Asistencia Sanitaria [Institute for the Improvement of Healthcare Foundation] (Fundación IMAS) to learn about the structure, organisation and operation of departments and units of endocrinology and nutrition (DENs). This project has two main sources of information: the RECALSEEN survey and the SNS minimum basic data set database. The RECALSEEN registry collects information on clinical nutrition units (CNUs) for the whole of Spain.

The first clinical nutrition units began to appear in Spain in the 1980s,1 and since 1990 they have been referred to as nutrition and dietetics units.2 Nowadays they may be independent or form part of sections, departments or clinical management units, and they are set up as cross-referral support units to hospital medical and surgical departments.3 Despite this, there are still hospitals with nutritional support teams that exclusively deal with artificial nutrition, and some centres with neither of the two structures for clinical nutrition management.

New techniques and treatments are constantly being incorporated into patients' nutritional therapy, requiring a multidisciplinary approach involving different healthcare professionals. Artificial nutrition (AN) is one of the most representative examples of coordinated therapeutic programmes,4 and so it must be developed and suitably organised. Back in 2003, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe indicated the need for an organised healthcare structure responsible for clinical and dietary nutrition in our hospitals, and the importance of the multidisciplinary nature of the participating healthcare professionals.5

The purpose of our article is to present the results of the RECALSEEN study6 on professional and organisational matters of clinical nutrition and the structure and operation thereof, and to assess the changes that must be made to suitably respond to these challenges and the demands of patients, the health system and civil society in general.

Material and methodsData were obtained from the RECALSEEN study, a cross-sectional, descriptive study of SNS DENs reported in 2016. The study variables were collected using an ad hoc questionnaire accessible via the website using personalised access codes for each DEN manager. The survey was conducted from March to September 2017. All the information presented was obtained from the survey.

Statistical analysisQualitative variables were reported in terms of frequency distributions (number of cases and percentages), and quantitative variables were reported in terms of mean, median, and standard deviation (SD). The chi-squared test was used to compare qualitative variables, and Student's t test was used to compare quantitative variables. In all comparisons, the null hypothesis was rejected, with an alpha error of less than 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with STATA version 13.0.

ResultsIn the RECALSEEN study, 88 DENs completed the survey, out of a total of 125 acute general SNS hospitals with 200 or more beds. Responses were obtained from 70% of the centres, with a relative weight of beds of 69% and 58% of the total estimated population in the area of influence of the respective hospitals. Forty-six of the DENs that completed the survey were in hospitals with more than 500 beds. Of the DENs that responded, 47% were departments and 31% were sections; 14% lacked their own organisational body (consisted of endocrinologists who belonged to an internal medicine workforce). The median number of endocrinologists assigned to the department was seven, but with very wide variations (average: 7.4 + 4.5). Therefore, the sample was highly representative of the overall situation of DENs throughout the SNS. There were, however, variations in response rate between autonomous regions, with a response rate below 50% for DENs in five of these regions (Canary Islands, Cantabria, Extremadura, Murcia and Rioja).

Data on the presence of clinical nutrition units in hospitalsEighty-three per cent of DENs had a CNU. This percentage rose to 98% in hospitals with 500 or more beds.

Data on human resources in the clinical nutrition unitsIt should be noted that in relation to healthcare personnel working in CNUs, it was not possible to determine the number of physicians per department dedicated to clinical nutrition, because this data was not specified.

DENs have a median of one nurse dedicated to nutrition, but 35% of DENs do not have a dedicated nurse (26% of DENs that have an integrated nutrition unit do not have a nurse). Staffing levels of dieticians, nutrition technicians and food scientists in CNUs are low. Among DENs with a nutrition unit, 53% had dieticians integrated into the unit. There were on average 2.6 dieticians per unit, although with significant variations (median: 1); in many cases, these dieticians had no employment contract with the hospital or had such a contract through a research project. Twenty-six per cent of DENs have nutrition technicians; the average number is 3.4, but this varies widely by DEN (median: 1). Having a food scientist in the CNU is very rare; only three of the DENs with an integrated nutrition unit reported having incorporated food scientists.

Data on material resources in the clinical nutrition unitsIn relation to consultation rooms, the median number assigned to nutrition was 1.7 + 0.9.

Data on the existence of specific units and techniques related to clinical nutritionDENs in hospitals with 500 or more beds were more complex, with a broad range of services provided by specialised units (Fig. 1). More than 50% of DENs had specific units for morbid obesity, and there was a notable diversity in the range of services offered by the respective DENs. Home artificial nutrition (parenteral and enteral) was provided by more than 50% of DENs (70.5% overall and 81% of DENs with an integrated nutrition unit). However, only 44% of DENs were able to provide home parenteral nutrition specifically. Bioelectrical impedance analysis was used at 38% of hospitals with <500 beds and 78% of hospitals with >500 beds. Fig. 2 shows techniques related to clinical nutrition by hospital size.

There are also wide variations in the use of the different techniques in terms of both average number of techniques used by DENs and frequency of use by area. Table 1 shows the average, median and standard deviation for both the number of examinations per unit (referring to those units that use the technique) and the frequency of use of each technique (estimated for the entire population included in the sample, probably resulting in underestimation) for some procedures, selected for being the most common in DENs.

Activity and frequency of use of endocrinology techniques related to clinical nutrition.

| Average |

| Home nutrition 548.3 |

| Median |

| Home nutrition 255 |

| SD |

| Home nutrition 732.1 |

| Freq.a |

| Home nutrition 0.9 |

Some 56% of DENs performed a nutritional assessment (malnutrition screening test) in admitted patients and some 14% of DENs did so in all admitted patients. The percentage of hospitals that performed a nutritional assessment rose to 66% in DENs with an integrated nutrition unit (with 19% of these DENs doing so in all admitted patients).

-Minimum basic data set, Sociedad Española de Nutrición [Spanish Society of Nutrition], and its relationship to clinical nutritionThe number of discharges from DEN gradually decreased over the period analysed, from 10,656 in 2007 to 8,698 in 2015. Annual discharges from DENs per 100,000 population over 17 years of age, decreased significantly, from a rate of 29 in 2007 to 23 in 2015 (–20%). This probably reflects a shift towards outpatient care in endocrinology and nutrition. That shift has been accompanied by a decrease in mean duration of hospital stay recorded in DEN discharges from 7.4 days in 2007 to 6 days in 2015. However, CNUs are removed from this context, as they are set up as cross-referral support units to other hospital medical and surgical departments in which the number of episodes with a secondary diagnosis of malnutrition increased by 116% in 2015 compared to 2007, being identified in 12.3 out of every 1,000 discharges (all ages included) in 2015. Malnutrition as a comorbidity is most commonly associated with a primary diagnosis of sepsis (5.9%), followed by pneumonia (5.2%), pneumonitis due to solids and liquids (3.9%), urinary infection (3.9%), heart failure (3.5%) and femoral neck fracture (3.5%).

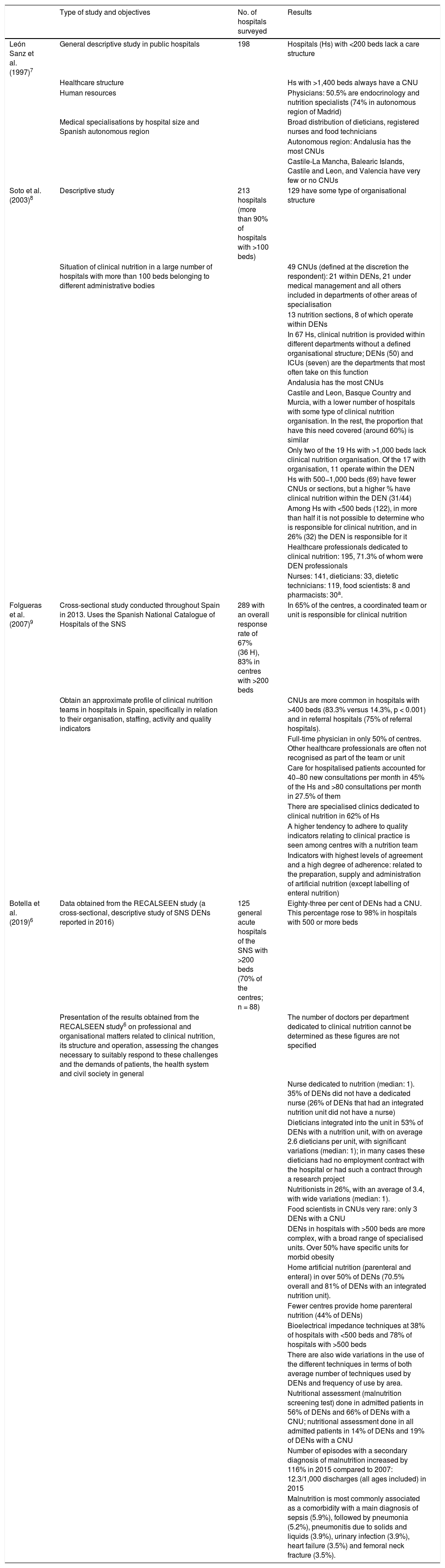

DiscussionBefore 2017, only two articles had been published on the organisation structure and provision of care in clinical nutrition in Spain — one in 1997 by León and García Luna7 and the other in 2003 by Soto et al.8 — both in the Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición journal Endocrinología y Nutrición. The main conclusions of the latter of these two articles were that 60% of the hospitals had some type of structure dedicated to clinical nutrition, compared to 40% in 1995, and that of all medical professionals dedicated to clinical nutrition, 71.2% were endocrinology and nutrition specialists, compared to 50% in 1995.

In 2017, a cross-sectional study conducted in 2013 by the Sociedad Española de Nutrición Clínica y Metabolismo [Spanish Society of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism] (SENPE) management working group was published. In it, a structured survey sent to a random sample of 20% of hospitals in the SNS network.9 The aim had been to obtain a rough profile of clinical nutrition teams in hospitals in Spain, specifically in terms of their organisation, staffing, activity and quality indicators. The study’s main conclusions were that such teams and CNUs were widely integrated into Spanish hospitals. Clinical nutrition care was organised through CNUs or nutritional support teams made up of healthcare professionals who dedicated most of their time to clinical nutrition in more than half of hospitals. As was to be expected, this was more common in large centres, which were more likely to have a true multidisciplinary organisational structure, but had to take on high workloads in relation to numbers of staff members dedicated to nutrition. Thus there was considerable heterogeneity among hospitals in terms of both numbers and types of interventions made by staff. Only 50% of centres with a CNU or support team had a physician working with them full time, and just 40% had a pharmacist in that capacity. This percentage was even lower for all other professional categories. What was also clear was that the existence of well-organised structures can be accompanied by benefits with a direct impact on care quality.9

Similar initiatives to roughly profile clinical nutrition provision in other European hospitals have been carried out since the late 1990s. There was one study conducted in 12 European countries with the support of the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN),10 but it only considered university hospitals (n = 199). Furthermore, it did not define what constituted a CNU and only obtained 36% of potential responses.

Other studies from countries such as Germany,11 Portugal,12 Austria and Switzerland13 were subsequently published. The methodology in each study was different, and the participation rates and results were highly variable, particularly with regard to the structure of the CNUs.

The 2017 RECALSEEN survey brought to light important aspects about clinical nutrition organisation, structure and management. According to the survey, 83% of all DENs had a CNU, with this figure rising to 98% in hospitals with 500 or more beds. The number of registered nurses who actively participated in clinical nutrition was high, but the number of pharmacists was not, and such participation by food scientists was very rare. There seemed to be a far larger number of registered dieticians compared to nutrition and dietetic technicians.

Endocrinologists are playing a much bigger role in inter-hospital referrals, and this is clearly related to the development of clinical nutrition. Endocrinologists are also participating more in multidisciplinary units related to clinical nutrition (such as bariatric surgery and eating disorder units). It should be noted that, due to the involvement of physicians dedicated to clinical nutrition, over 50% of DENs carry out a nutritional assessment on admitted patients (malnutrition screening test) and provide home artificial nutrition services. Although among patients admitted to DENs the main diagnoses that appear in discharge reports are only related to clinical nutrition in a small number of cases, the number of episodes with a secondary diagnosis of malnutrition has increased greatly. This is probably in relation to the significant increase in the weight of the diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) when the diagnosis of malnutrition and/or the artificial nutrition procedure used in each case is added.14

Table 2 shows a comparison of the studies published on organisation and care provision in hospital clinical nutrition in Spain over the last 25 years.

Comparison of published studies on organisation and care provision in hospital clinical nutrition in Spain.

| Type of study and objectives | No. of hospitals surveyed | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|

| León Sanz et al. (1997)7 | General descriptive study in public hospitals | 198 | Hospitals (Hs) with <200 beds lack a care structure |

| Healthcare structure | Hs with >1,400 beds always have a CNU | ||

| Human resources | Physicians: 50.5% are endocrinology and nutrition specialists (74% in autonomous region of Madrid) | ||

| Medical specialisations by hospital size and Spanish autonomous region | Broad distribution of dieticians, registered nurses and food technicians | ||

| Autonomous region: Andalusia has the most CNUs | |||

| Castile-La Mancha, Balearic Islands, Castile and Leon, and Valencia have very few or no CNUs | |||

| Soto et al. (2003)8 | Descriptive study | 213 hospitals (more than 90% of hospitals with >100 beds) | 129 have some type of organisational structure |

| Situation of clinical nutrition in a large number of hospitals with more than 100 beds belonging to different administrative bodies | 49 CNUs (defined at the discretion the respondent): 21 within DENs, 21 under medical management and all others included in departments of other areas of specialisation | ||

| 13 nutrition sections, 8 of which operate within DENs | |||

| In 67 Hs, clinical nutrition is provided within different departments without a defined organisational structure; DENs (50) and ICUs (seven) are the departments that most often take on this function | |||

| Andalusia has the most CNUs | |||

| Castile and Leon, Basque Country and Murcia, with a lower number of hospitals with some type of clinical nutrition organisation. In the rest, the proportion that have this need covered (around 60%) is similar | |||

| Only two of the 19 Hs with >1,000 beds lack clinical nutrition organisation. Of the 17 with organisation, 11 operate within the DEN | |||

| Hs with 500−1,000 beds (69) have fewer CNUs or sections, but a higher % have clinical nutrition within the DEN (31/44) | |||

| Among Hs with <500 beds (122), in more than half it is not possible to determine who is responsible for clinical nutrition, and in 26% (32) the DEN is responsible for it | |||

| Healthcare professionals dedicated to clinical nutrition: 195, 71.3% of whom were DEN professionals | |||

| Nurses: 141, dieticians: 33, dietetic technicians: 119, food scientists: 8 and pharmacists: 30a. | |||

| Folgueras et al. (2007)9 | Cross-sectional study conducted throughout Spain in 2013. Uses the Spanish National Catalogue of Hospitals of the SNS | 289 with an overall response rate of 67% (36 H), 83% in centres with >200 beds | In 65% of the centres, a coordinated team or unit is responsible for clinical nutrition |

| Obtain an approximate profile of clinical nutrition teams in hospitals in Spain, specifically in relation to their organisation, staffing, activity and quality indicators | CNUs are more common in hospitals with >400 beds (83.3% versus 14.3%, p < 0.001) and in referral hospitals (75% of referral hospitals). | ||

| Full-time physician in only 50% of centres. Other healthcare professionals are often not recognised as part of the team or unit | |||

| Care for hospitalised patients accounted for 40−80 new consultations per month in 45% of the Hs and >80 consultations per month in 27.5% of them | |||

| There are specialised clinics dedicated to clinical nutrition in 62% of Hs | |||

| A higher tendency to adhere to quality indicators relating to clinical practice is seen among centres with a nutrition team | |||

| Indicators with highest levels of agreement and a high degree of adherence: related to the preparation, supply and administration of artificial nutrition (except labelling of enteral nutrition) | |||

| Botella et al. (2019)6 | Data obtained from the RECALSEEN study (a cross-sectional, descriptive study of SNS DENs reported in 2016) | 125 general acute hospitals of the SNS with >200 beds (70% of the centres; n = 88) | Eighty-three per cent of DENs had a CNU. This percentage rose to 98% in hospitals with 500 or more beds |

| Presentation of the results obtained from the RECALSEEN study6 on professional and organisational matters related to clinical nutrition, its structure and operation, assessing the changes necessary to suitably respond to these challenges and the demands of patients, the health system and civil society in general | The number of doctors per department dedicated to clinical nutrition cannot be determined as these figures are not specified | ||

| Nurse dedicated to nutrition (median: 1). 35% of DENs did not have a dedicated nurse (26% of DENs that had an integrated nutrition unit did not have a nurse) | |||

| Dieticians integrated into the unit in 53% of DENs with a nutrition unit, with on average 2.6 dieticians per unit, with significant variations (median: 1); in many cases these dieticians had no employment contract with the hospital or had such a contract through a research project | |||

| Nutritionists in 26%, with an average of 3.4, with wide variations (median: 1). | |||

| Food scientists in CNUs very rare: only 3 DENs with a CNU | |||

| DENs in hospitals with >500 beds are more complex, with a broad range of specialised units. Over 50% have specific units for morbid obesity | |||

| Home artificial nutrition (parenteral and enteral) in over 50% of DENs (70.5% overall and 81% of DENs with an integrated nutrition unit). | |||

| Fewer centres provide home parenteral nutrition (44% of DENs) | |||

| Bioelectrical impedance techniques at 38% of hospitals with <500 beds and 78% of hospitals with >500 beds | |||

| There are also wide variations in the use of the different techniques in terms of both average number of techniques used by DENs and frequency of use by area. | |||

| Nutritional assessment (malnutrition screening test) done in admitted patients in 56% of DENs and 66% of DENs with a CNU; nutritional assessment done in all admitted patients in 14% of DENs and 19% of DENs with a CNU | |||

| Number of episodes with a secondary diagnosis of malnutrition increased by 116% in 2015 compared to 2007: 12.3/1,000 discharges (all ages included) in 2015 | |||

| Malnutrition is most commonly associated as a comorbidity with a main diagnosis of sepsis (5.9%), followed by pneumonia (5.2%), pneumonitis due to solids and liquids (3.9%), urinary infection (3.9%), heart failure (3.5%) and femoral neck fracture (3.5%). |

What seems clear is that clinical nutrition care has changed gradually. It is present in most hospitals and is receiving more and more attention due to the importance of managing disease-related malnutrition, a significant problem in both hospital and community settings in patients with complex chronic diseases and patients with cancer, or due to the considerable ageing of the patients seen in hospital wards across various medical specialisations.15,16 These population groups have specific requirements, including attention to their nutritional status, as well as conditions rendering them frail and vulnerable that carry certain risks during hospitalisation, as they may worsen if not cared for properly and lead to readmission.17–19 In this context, CNUs are essential for improving the quality of life of these patients and preventing such readmission.15

The current growth of the specialisation is largely due to the demand for care created by hospital clinical nutrition, and the number of hospitals with nutrition units is gradually increasing as a result. Nevertheless, development and staffing levels of endocrinologists dedicated to the field of clinical nutrition remain insufficient in most hospitals.6,9 This is all the more true so in the light of the new healthcare scenario, with multidisciplinary units of shared disorders (gastrointestinal tumours, head and neck cancers, non-cancerous gastrointestinal tumours, morbid obesity, cardiovascular disease and rehabilitation, eating disorders, etc). However, we are receiving increasing numbers of requests for advice on how to preserve patients’ state of health in relation to matters of diet, lifestyle and disease prevention. This situation will compel future endocrinologists to position themselves as leaders efforts to promote nutrition and health, both inside and outside the hospital setting. We firmly believe that nutrition is an area in increasing demand by the population, and that endocrinology and nutrition specialists currently in training will face this demand in their future careers. However, we also suspect that the specialisation has not adapted enough to face the change and continues to dichotomise endocrinology and nutrition (editorial quote).20

The limitations of our study include the need for caution in interpreting the reliability of the estimates in relation to the differences between autonomous communities of Spain. This depends on, among other factors, the representativeness of the sample in each autonomous region (the higher the percentages of responses obtained, the more reliable the estimates) and the degree of possible bias — for example, in relation to the size of the hospitals where the DENs are located.

ConclusionsAt this time, with the data obtained in the RECALSEEN study, it can be said that the vast majority of hospitals have a CNU integrated into the DEN, although their staffing levels are low.

However, as the study sample was large, it does not seem too bold to state that there are probably significant differences between health departments in terms of resources and activity in our specialisation, and that clinical nutrition is a priority area for improvement in hospitals with fewer than 500 beds.

It is therefore perfectly reasonable to insist that the development of CNUs, which have so clearly demonstrated their role as cross-referral support units, both to hospitals’ medical and surgical departments and to the community, must be supported with the necessary resources.

FundingThe RECALSEEN study received an unconditional grant from Laboratorios Menarini.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Cancer Minchot E, Elola Somoza FJ, Fernández Pérez C, Bernal Sobrino JL, Bretón Lesmes I, Botella Romero F. RECALSEEN. Subgrupo: la atención al paciente en las unidades de nutrición clínica del Sistema Nacional de Salud. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2021;68:354–362.