The Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) care pathways include evidence-based items designed to accelerate recovery after surgery. Interdisciplinarity is one of the key points of ERAS programs.

ObjectiveTo prepare a consensus document among the members of the Nutrition Area of the Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition (SEEN) and the Spanish Group for Multimodal Rehabilitation (GERM), in which the goal is to homogenize the nutritional and metabolic management of patients included in an ERAS program.

Methods69 specialists in Endocrinology and Nutrition and 85 members of the GERM participated in the project. After a literature review, 79 statements were proposed, divided into 5 sections: 17 of general characteristics, 28 referring to the preoperative period, 4 to the intraoperative, 13 to the perioperative and 17 to the postoperative period. The degree of consensus was determined through a Delphi process of 2 circulations that was ratified by a consistency analysis.

ResultsOverall, in 61 of the 79 statements there was a consistent agreement, with the degree of consensus being greater among members of the SEEN (64/79) than members of the GERM (59/79). Within the 18 statements where a consistent agreement was not reached, we should highlight some important nutritional strategies such as muscle mass assessment, the start of early oral feeding or pharmaconutrition.

ConclusionConsensus was reached on the vast majority of the nutritional measures and care included in ERAS programs. Due to the lack of agreement on certain key points, it is necessary to continue working closely with both societies to improve the recovery of the surgical patients.

La recuperación Intensificada en cirugía abdominal (RICA), constituye un conjunto de estrategias perioperatorias encaminadas a acelerar la recuperación del paciente. La interdisciplinariedad es uno de los puntos claves de los programas RICA.

ObjetivoElaborar un documento de consenso entre los miembros del Área de Nutrición de la Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición (SEEN) y del Grupo Español de Rehabilitación Multimodal (GERM), donde se intente homogeneizar el manejo nutricional y metabólico de los pacientes incluidos en un programa RICA.

MétodosHan participado 69 especialistas en Endocrinología y Nutrición y 85 miembros del GERM. Tras una revisión bibliográfica fueron propuestas 79 aseveraciones divididas en 5 apartados: 17 de carácter general, 28 referidas al preoperatorio, 4 al intraoperatorio, 13 al perioperatorio y 17 al postoperatorio. Se determinó el grado de acuerdo a través de un proceso Delphi de 2 circulaciones que fue ratificado mediante un análisis de consistencia.

ResultadosDe forma global, en 61 de los 79 enunciados hubo un acuerdo consistente, siendo mayor el grado de consenso entre los miembros de la SEEN (64/79) que en los del GERM (59/79). Dentro de las 18 aseveraciones donde no se alcanzó un acuerdo consistente cabe destacar algunas estrategias nutricionales importantes como la valoración la masa muscular, el inicio de la alimentación precoz o la farmaconutrición.

ConclusiónQueda consensuada la gran mayoría de las medidas y los cuidados nutricionales incluidos en los programas RICA. Debido a la falta de acuerdo en algunos puntos claves, es necesario seguir colaborando estrechamente entre ambas sociedades para mejorar la recuperación del paciente quirúrgico.

Multimodal rehabilitation in surgery or Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) in Europe, is a new approach to the care and management of the surgical patient aimed at minimising the metabolic stress caused by surgery, maintaining physical function and accelerating the patient’s recovery.1 The ERAS programmes cover the entire surgical process from the time of diagnosis to full incorporation back into normal activity after surgery has been conducted. All this requires the close and structured understanding and collaboration of all the health professionals involved, such as surgeons, anaesthesiologists, endocrinologists, nurses, etc., in addition to the active participation of the patient him or herself throughout the process.2

Some multicentre observational studies and meta-analyses have shown that the implementation of ERAS protocols is safe and beneficial for the patient, since they are associated with a lower rate of postoperative complications and a reduction in hospital stay and health care costs.3–5 It has been documented that the benefit in reducing postoperative morbidity is directly related to compliance or adherence to all the perioperative measures included in the ERAS programmes.6

Due to the growing interest of Endocrinology and Nutrition specialists in the ERAS programmes, the Nutrition Department Management Committee of the Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición (SEEN) has promoted the NutRICA (nutritional and metabolic therapy in ERAS) multidisciplinary project and has invited the Grupo Español de Rehabilitación Multimodal (GERM) to participate, with the main objective to prepare a consensus document defining and establishing the metabolic and nutritional approach in the perioperative period of patients included in an ERAS programme.

Material and methodsThe project was carried out between the months of November 2018 and March 2019, framed within the scientific activity carried out by the SEEN Nutrition Department. The SEEN secretary invited all members of the Nutrition Department to participate via email and the same thing occurred with the GERM secretary.

In a first phase, a combined systematic bibliographic search was carried out in Medline, PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, the websites of the European Society of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN), the ERAS Society and the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, as well as the ERAS route and the Guía de práctica clínica sobre cuidados perioperatorios en cirugía mayor abdominal [clinical practice guidelines on perioperative care in major abdominal surgery], both published by the Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality, in addition to the clinical practice guidelines published by each of the entities named above,2,7–11

As a result of the literature review, 79 statements classified into five blocks were selected: 17 related to generalities, 28 to the preoperative period, four to the intraoperative period, 13 to the perioperative period, and 17 to the postoperative period.

The second phase of the study involved the implementation of a Delphi process of two circulations to determine the degree of agreement with the proposed statements. For this, a specific email was generated, and the questionnaire was sent via personal email to the registered members. The degree of agreement was assessed on a numerical Likert scale from one to nine, with one being the minimum agreement and nine being the maximum assessment. The second circulation was sent to those who responded to the first questionnaire, and as a guide, the median value and the interquartile range (IQR) resulting from the assignment of the first circulation were provided, highlighting those cases in which the IQR was greater than one.

A descriptive analysis was carried out determining, for the 79 statements, the mean and its standard deviation (SD), the median and the IQR as a measure of dispersion. Consistency of agreement was considered if the IQR was ≤1. On the contrary, if the IQR was >1, the dispersion was considered excessive and therefore the agreements were inconsistent.

To compare the results obtained between the members of the SEEN and the GERM, the Student’s t-statistic for contrasting means was used at a confidence level of 95%.

Results73 specialists in Endocrinology and Nutrition were enrolled, of whom 69 participants completed the two circulations of the Delphi process. Of the 120 members of the GERM who initially enrolled, 85 participants completed the project (both circulations), corresponding to 57 surgeons, two gynaecologists, three urologists and 23 anaesthesiologists.

Together, the specialists from both organisations came from 60 Spanish hospitals with a mean of 666 (SD 387.28) beds, representing the 17 autonomous communities. The participants had a mean of 18.43 (SD 9.48) years' experience, with 75% of them being area specialists, 8% department/section heads, and 6% resident medical interns who had already completed their training period in a Nutrition Unit.

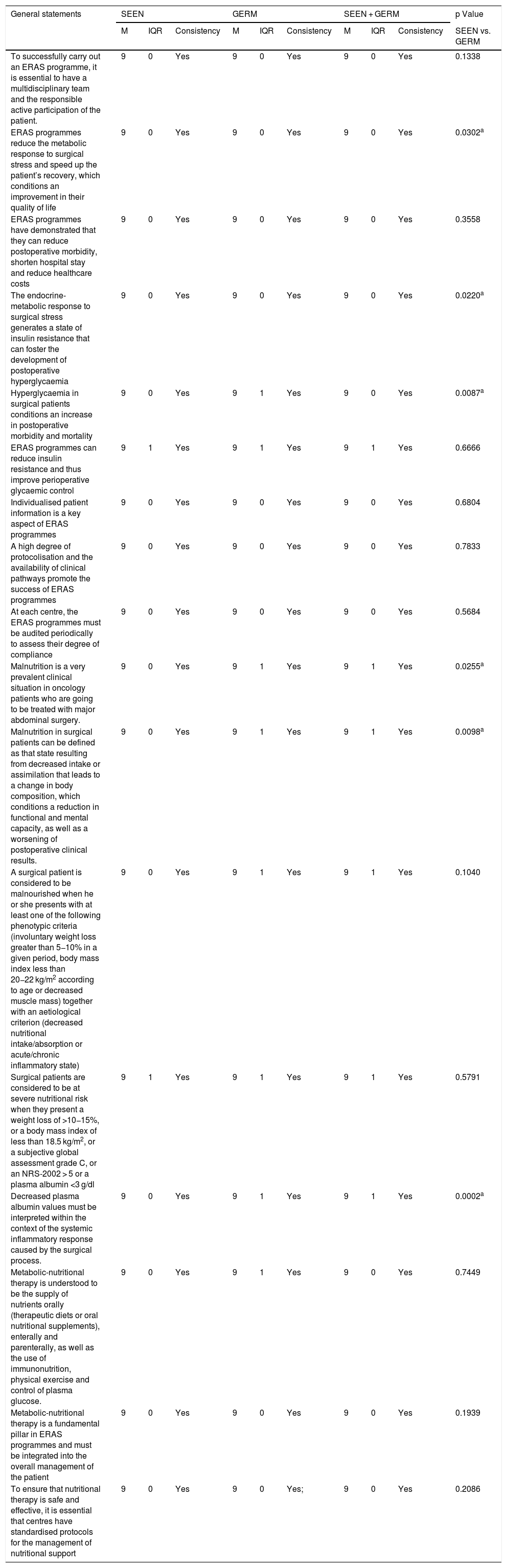

The degree of agreement is set out in Tables 1–5. In summary, a greater degree of agreement was observed among the members of the SEEN compared to the members of the GERM. Within the SEEN group, there was consistent agreement in 64 of the 79 statements compared to the GERM group where consistency was reached in 59 statements.

Degree of agreement of the statements related to general aspects.

| General statements | SEEN | GERM | SEEN + GERM | p Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | IQR | Consistency | M | IQR | Consistency | M | IQR | Consistency | SEEN vs. GERM | |

| To successfully carry out an ERAS programme, it is essential to have a multidisciplinary team and the responsible active participation of the patient. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.1338 |

| ERAS programmes reduce the metabolic response to surgical stress and speed up the patient’s recovery, which conditions an improvement in their quality of life | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.0302a |

| ERAS programmes have demonstrated that they can reduce postoperative morbidity, shorten hospital stay and reduce healthcare costs | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.3558 |

| The endocrine-metabolic response to surgical stress generates a state of insulin resistance that can foster the development of postoperative hyperglycaemia | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.0220a |

| Hyperglycaemia in surgical patients conditions an increase in postoperative morbidity and mortality | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.0087a |

| ERAS programmes can reduce insulin resistance and thus improve perioperative glycaemic control | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 0.6666 |

| Individualised patient information is a key aspect of ERAS programmes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.6804 |

| A high degree of protocolisation and the availability of clinical pathways promote the success of ERAS programmes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.7833 |

| At each centre, the ERAS programmes must be audited periodically to assess their degree of compliance | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.5684 |

| Malnutrition is a very prevalent clinical situation in oncology patients who are going to be treated with major abdominal surgery. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 0.0255a |

| Malnutrition in surgical patients can be defined as that state resulting from decreased intake or assimilation that leads to a change in body composition, which conditions a reduction in functional and mental capacity, as well as a worsening of postoperative clinical results. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 0.0098a |

| A surgical patient is considered to be malnourished when he or she presents with at least one of the following phenotypic criteria (involuntary weight loss greater than 5−10% in a given period, body mass index less than 20−22 kg/m2 according to age or decreased muscle mass) together with an aetiological criterion (decreased nutritional intake/absorption or acute/chronic inflammatory state) | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 0.1040 |

| Surgical patients are considered to be at severe nutritional risk when they present a weight loss of >10−15%, or a body mass index of less than 18.5 kg/m2, or a subjective global assessment grade C, or an NRS-2002 > 5 or a plasma albumin <3 g/dl | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 0.5791 |

| Decreased plasma albumin values must be interpreted within the context of the systemic inflammatory response caused by the surgical process. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 0.0002a |

| Metabolic-nutritional therapy is understood to be the supply of nutrients orally (therapeutic diets or oral nutritional supplements), enterally and parenterally, as well as the use of immunonutrition, physical exercise and control of plasma glucose. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.7449 |

| Metabolic-nutritional therapy is a fundamental pillar in ERAS programmes and must be integrated into the overall management of the patient | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.1939 |

| To ensure that nutritional therapy is safe and effective, it is essential that centres have standardised protocols for the management of nutritional support | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes; | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.2086 |

M: median; GERM: Grupo Español de Rehabilitación Multimodal [Spanish Multimodal Rehabilitation Group]; IQR: interquartile range, ERAS: Enhanced recovery after abdominal surgery; SEEN: Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición [Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition].

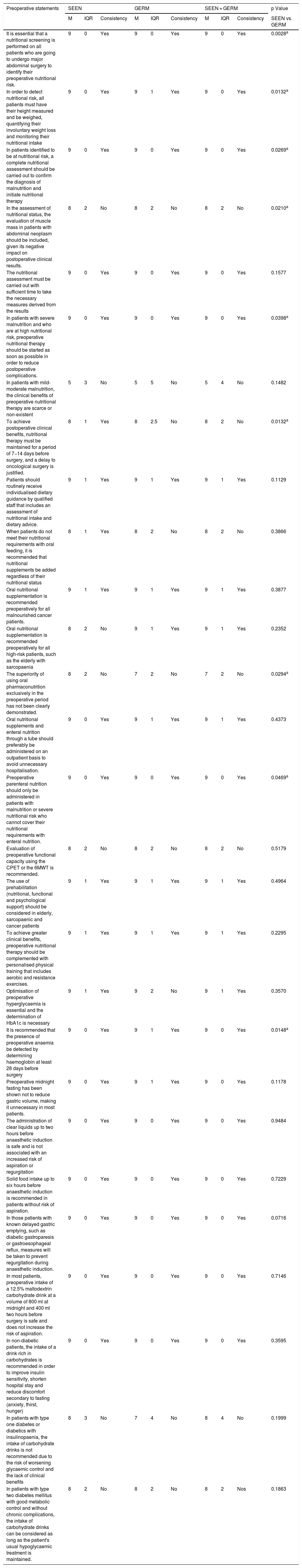

Degree of agreement of the statements related to preoperative aspects.

| Preoperative statements | SEEN | GERM | SEEN + GERM | p Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | IQR | Consistency | M | IQR | Consistency | M | IQR | Consistency | SEEN vs. GERM | |

| It is essential that a nutritional screening is performed on all patients who are going to undergo major abdominal surgery to identify their preoperative nutritional risk. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.0028a |

| In order to detect nutritional risk, all patients must have their height measured and be weighed, quantifying their involuntary weight loss and monitoring their nutritional intake | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.0132a |

| In patients identified to be at nutritional risk, a complete nutritional assessment should be carried out to confirm the diagnosis of malnutrition and initiate nutritional therapy | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.0269a |

| In the assessment of nutritional status, the evaluation of muscle mass in patients with abdominal neoplasm should be included, given its negative impact on postoperative clinical results. | 8 | 2 | No | 8 | 2 | No | 8 | 2 | No | 0.0210a |

| The nutritional assessment must be carried out with sufficient time to take the necessary measures derived from the results | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.1577 |

| In patients with severe malnutrition and who are at high nutritional risk, preoperative nutritional therapy should be started as soon as possible in order to reduce postoperative complications. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.0398a |

| In patients with mild-moderate malnutrition, the clinical benefits of preoperative nutritional therapy are scarce or non-existent | 5 | 3 | No | 5 | 5 | No | 5 | 4 | No | 0.1482 |

| To achieve postoperative clinical benefits, nutritional therapy must be maintained for a period of 7−14 days before surgery, and a delay to oncological surgery is justified. | 8 | 1 | Yes | 8 | 2.5 | No | 8 | 2 | No | 0.0132a |

| Patients should routinely receive individualised dietary guidance by qualified staff that includes an assessment of nutritional intake and dietary advice. | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 0.1129 |

| When patients do not meet their nutritional requirements with oral feeding, it is recommended that nutritional supplements be added regardless of their nutritional status | 8 | 1 | Yes | 8 | 2 | No | 8 | 2 | No | 0.3866 |

| Oral nutritional supplementation is recommended preoperatively for all malnourished cancer patients. | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 0.3877 |

| Oral nutritional supplementation is recommended preoperatively for all high-risk patients, such as the elderly with sarcopaenia | 8 | 2 | No | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 0.2352 |

| The superiority of using oral pharmaconutrition exclusively in the preoperative period has not been clearly demonstrated. | 8 | 2 | No | 7 | 2 | No | 7 | 2 | No | 0.0294a |

| Oral nutritional supplements and enteral nutrition through a tube should preferably be administered on an outpatient basis to avoid unnecessary hospitalisation. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 0.4373 |

| Preoperative parenteral nutrition should only be administered in patients with malnutrition or severe nutritional risk who cannot cover their nutritional requirements with enteral nutrition. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.0469a |

| Evaluation of preoperative functional capacity using the CPET or the 6MWT is recommended. | 8 | 2 | No | 8 | 2 | No | 8 | 2 | No | 0.5179 |

| The use of prehabilitation (nutritional, functional and psychological support) should be considered in elderly, sarcopaenic and cancer patients | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 0.4964 |

| To achieve greater clinical benefits, preoperative nutritional therapy should be complemented with personalised physical training that includes aerobic and resistance exercises. | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 0.2295 |

| Optimisation of preoperative hyperglycaemia is essential and the determination of HbA1c is necessary | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 2 | No | 9 | 1 | Yes | 0.3570 |

| It is recommended that the presence of preoperative anaemia be detected by determining haemoglobin at least 28 days before surgery | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.0148a |

| Preoperative midnight fasting has been shown not to reduce gastric volume, making it unnecessary in most patients. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.1178 |

| The administration of clear liquids up to two hours before anaesthetic induction is safe and is not associated with an increased risk of aspiration or regurgitation | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.9484 |

| Solid food intake up to six hours before anaesthetic induction is recommended in patients without risk of aspiration. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.7229 |

| In those patients with known delayed gastric emptying, such as diabetic gastroparesis or gastroesophageal reflux, measures will be taken to prevent regurgitation during anaesthetic induction. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.0716 |

| In most patients, preoperative intake of a 12.5% maltodextrin carbohydrate drink at a volume of 800 ml at midnight and 400 ml two hours before surgery is safe and does not increase the risk of aspiration. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.7146 |

| In non-diabetic patients, the intake of a drink rich in carbohydrates is recommended in order to improve insulin sensitivity, shorten hospital stay and reduce discomfort secondary to fasting (anxiety, thirst, hunger) | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.3595 |

| In patients with type one diabetes or diabetics with insulinopaenia, the intake of carbohydrate drinks is not recommended due to the risk of worsening glycaemic control and the lack of clinical benefits | 8 | 3 | No | 7 | 4 | No | 8 | 4 | No | 0.1999 |

| In patients with type two diabetes mellitus with good metabolic control and without chronic complications, the intake of carbohydrate drinks can be considered as long as the patient's usual hypoglycaemic treatment is maintained. | 8 | 2 | No | 8 | 2 | No | 8 | 2 | Nos | 0.1863 |

CPET: cardiopulmonary exercise testing; GERM: Grupo Español de Rehabilitación Multimodal [Spanish Multimodal Rehabilitation Group]; HbA1c: glycosylated haemoglobin; M: median; IQR: interquartile range; SEEN: Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición [Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition]; 6MWT: six-minute walk test.

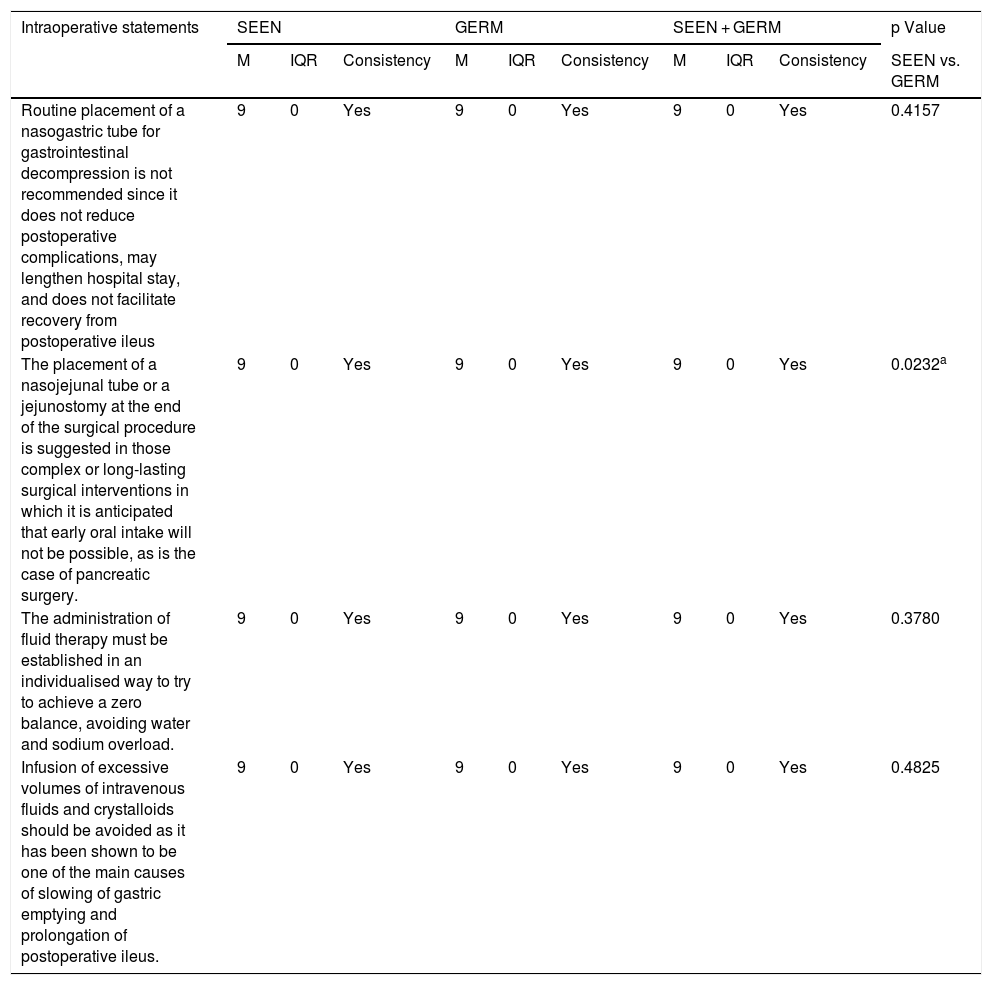

Degree of agreement of the statements related to intraoperative aspects.

| Intraoperative statements | SEEN | GERM | SEEN + GERM | p Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | IQR | Consistency | M | IQR | Consistency | M | IQR | Consistency | SEEN vs. GERM | |

| Routine placement of a nasogastric tube for gastrointestinal decompression is not recommended since it does not reduce postoperative complications, may lengthen hospital stay, and does not facilitate recovery from postoperative ileus | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.4157 |

| The placement of a nasojejunal tube or a jejunostomy at the end of the surgical procedure is suggested in those complex or long-lasting surgical interventions in which it is anticipated that early oral intake will not be possible, as is the case of pancreatic surgery. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.0232a |

| The administration of fluid therapy must be established in an individualised way to try to achieve a zero balance, avoiding water and sodium overload. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.3780 |

| Infusion of excessive volumes of intravenous fluids and crystalloids should be avoided as it has been shown to be one of the main causes of slowing of gastric emptying and prolongation of postoperative ileus. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.4825 |

GERM: Grupo Español de Rehabilitación Multimodal [Spanish Multimodal Rehabilitation Group]; M: median; IQR: interquartile range; SEEN: Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición [Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition].

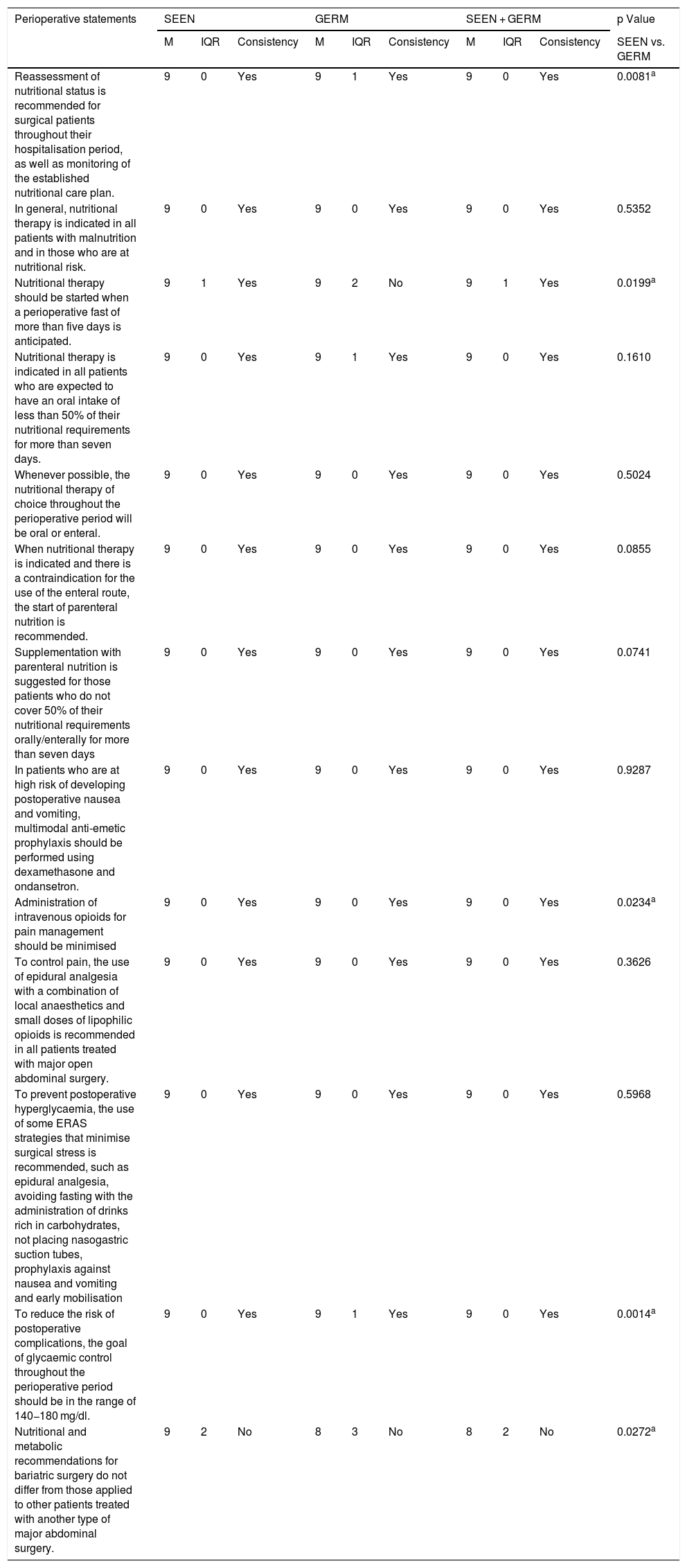

Degree of agreement of the statements related to perioperative aspects.

| Perioperative statements | SEEN | GERM | SEEN + GERM | p Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | IQR | Consistency | M | IQR | Consistency | M | IQR | Consistency | SEEN vs. GERM | |

| Reassessment of nutritional status is recommended for surgical patients throughout their hospitalisation period, as well as monitoring of the established nutritional care plan. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.0081a |

| In general, nutritional therapy is indicated in all patients with malnutrition and in those who are at nutritional risk. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.5352 |

| Nutritional therapy should be started when a perioperative fast of more than five days is anticipated. | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 2 | No | 9 | 1 | Yes | 0.0199a |

| Nutritional therapy is indicated in all patients who are expected to have an oral intake of less than 50% of their nutritional requirements for more than seven days. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.1610 |

| Whenever possible, the nutritional therapy of choice throughout the perioperative period will be oral or enteral. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.5024 |

| When nutritional therapy is indicated and there is a contraindication for the use of the enteral route, the start of parenteral nutrition is recommended. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.0855 |

| Supplementation with parenteral nutrition is suggested for those patients who do not cover 50% of their nutritional requirements orally/enterally for more than seven days | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.0741 |

| In patients who are at high risk of developing postoperative nausea and vomiting, multimodal anti-emetic prophylaxis should be performed using dexamethasone and ondansetron. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.9287 |

| Administration of intravenous opioids for pain management should be minimised | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.0234a |

| To control pain, the use of epidural analgesia with a combination of local anaesthetics and small doses of lipophilic opioids is recommended in all patients treated with major open abdominal surgery. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.3626 |

| To prevent postoperative hyperglycaemia, the use of some ERAS strategies that minimise surgical stress is recommended, such as epidural analgesia, avoiding fasting with the administration of drinks rich in carbohydrates, not placing nasogastric suction tubes, prophylaxis against nausea and vomiting and early mobilisation | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.5968 |

| To reduce the risk of postoperative complications, the goal of glycaemic control throughout the perioperative period should be in the range of 140−180 mg/dl. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 1 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.0014a |

| Nutritional and metabolic recommendations for bariatric surgery do not differ from those applied to other patients treated with another type of major abdominal surgery. | 9 | 2 | No | 8 | 3 | No | 8 | 2 | No | 0.0272a |

M: median; GERM: Grupo Español de Rehabilitación Multimodal [Spanish Multimodal Rehabilitation Group]; IQR: interquartile range; SEEN: Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición [Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition].

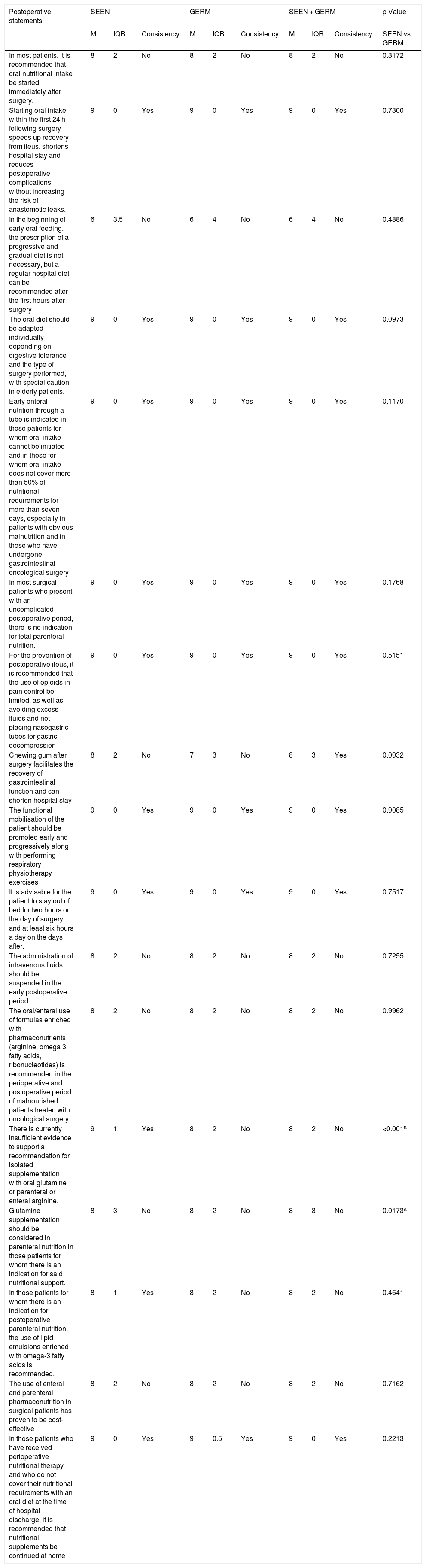

Degree of agreement of the statements related to postoperative aspects.

| Postoperative statements | SEEN | GERM | SEEN + GERM | p Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | IQR | Consistency | M | IQR | Consistency | M | IQR | Consistency | SEEN vs. GERM | |

| In most patients, it is recommended that oral nutritional intake be started immediately after surgery. | 8 | 2 | No | 8 | 2 | No | 8 | 2 | No | 0.3172 |

| Starting oral intake within the first 24 h following surgery speeds up recovery from ileus, shortens hospital stay and reduces postoperative complications without increasing the risk of anastomotic leaks. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.7300 |

| In the beginning of early oral feeding, the prescription of a progressive and gradual diet is not necessary, but a regular hospital diet can be recommended after the first hours after surgery | 6 | 3.5 | No | 6 | 4 | No | 6 | 4 | No | 0.4886 |

| The oral diet should be adapted individually depending on digestive tolerance and the type of surgery performed, with special caution in elderly patients. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.0973 |

| Early enteral nutrition through a tube is indicated in those patients for whom oral intake cannot be initiated and in those for whom oral intake does not cover more than 50% of nutritional requirements for more than seven days, especially in patients with obvious malnutrition and in those who have undergone gastrointestinal oncological surgery | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.1170 |

| In most surgical patients who present with an uncomplicated postoperative period, there is no indication for total parenteral nutrition. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.1768 |

| For the prevention of postoperative ileus, it is recommended that the use of opioids in pain control be limited, as well as avoiding excess fluids and not placing nasogastric tubes for gastric decompression | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.5151 |

| Chewing gum after surgery facilitates the recovery of gastrointestinal function and can shorten hospital stay | 8 | 2 | No | 7 | 3 | No | 8 | 3 | Yes | 0.0932 |

| The functional mobilisation of the patient should be promoted early and progressively along with performing respiratory physiotherapy exercises | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.9085 |

| It is advisable for the patient to stay out of bed for two hours on the day of surgery and at least six hours a day on the days after. | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.7517 |

| The administration of intravenous fluids should be suspended in the early postoperative period. | 8 | 2 | No | 8 | 2 | No | 8 | 2 | No | 0.7255 |

| The oral/enteral use of formulas enriched with pharmaconutrients (arginine, omega 3 fatty acids, ribonucleotides) is recommended in the perioperative and postoperative period of malnourished patients treated with oncological surgery. | 8 | 2 | No | 8 | 2 | No | 8 | 2 | No | 0.9962 |

| There is currently insufficient evidence to support a recommendation for isolated supplementation with oral glutamine or parenteral or enteral arginine. | 9 | 1 | Yes | 8 | 2 | No | 8 | 2 | No | <0.001a |

| Glutamine supplementation should be considered in parenteral nutrition in those patients for whom there is an indication for said nutritional support. | 8 | 3 | No | 8 | 2 | No | 8 | 3 | No | 0.0173a |

| In those patients for whom there is an indication for postoperative parenteral nutrition, the use of lipid emulsions enriched with omega-3 fatty acids is recommended. | 8 | 1 | Yes | 8 | 2 | No | 8 | 2 | No | 0.4641 |

| The use of enteral and parenteral pharmaconutrition in surgical patients has proven to be cost-effective | 8 | 2 | No | 8 | 2 | No | 8 | 2 | No | 0.7162 |

| In those patients who have received perioperative nutritional therapy and who do not cover their nutritional requirements with an oral diet at the time of hospital discharge, it is recommended that nutritional supplements be continued at home | 9 | 0 | Yes | 9 | 0.5 | Yes | 9 | 0 | Yes | 0.2213 |

M: median; GERM: Grupo Español de Rehabilitación Multimodal [Spanish Multimodal Rehabilitation Group]; IQR: interquartile range; SEEN: Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición [Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition].

There was uniformity of agreement between the two organisations in the 17 items related to general aspects of the ERAS programmes (Table 1) and in the four items related to intraoperative measures (Table 3).

Among the 28 statements that made reference to care in the preoperative period (Table 2), on eight occasions no agreement was reached between the two organisations on aspects such as functional and muscle mass assessment, the use of beverages rich in carbohydrates in diabetic patients or the indication of nutritional therapy.

Of the 13 statements related to ERAS strategies during the perioperative period (Table 4), there was no agreement between the two groups on only one occasion.

The largest number of items where a consistent agreement was not reached (Table 5) was related to postoperative care (nine of the 17 items), especially regarding such important aspects as the start of early feeding or pharmaconutrition.

DiscussionERAS protocols combine a series of perioperative strategies with the aim of reducing the response to surgical stress and optimising patient recovery.1 In 2015, the ERAS pathway,2 which was an interdisciplinary consensus document based on a set of clinical practice recommendations that reviews the entire perioperative process was published in Spain, and it is aimed not only at health professionals directly involved in the management of surgical patients, that is, surgeons or anaesthesiologists, but also at those professionals who are in some way related to the interdisciplinary treatment of these patients, such as Endocrinology and Nutrition specialists. The ERAS pathway was updated in 2020 and the SEEN was one of the scientific organisations that participated in the development of the new document.12

As far as we know, this is the first publication in Spain that aims to reach a consensus among the different professionals involved in the surgical process about the nutritional and metabolic strategies included in the ERAS protocols. The Delphi methodology is considered a good technique for evaluating an agreement or visualising a discrepancy between experts. The successive sending out of the questionnaires reduces dispersion and helps to specify the average consensus opinion.13

As can be seen in the tables, of the 79 selected items, 61 of them demonstrated consistent agreement, the degree of consensus being greater among the members of SEEN (64/79) than among those of GERM (59/79).

Within the preoperative period, one of the main ERAS strategies is nutritional optimisation. Preoperative malnutrition is associated with an increase in postoperative morbidity and mortality, hospital stay, re-admission rate and health costs related to the surgical patient.14 It is estimated that two out of three patients who are going to be treated with major surgery for gastrointestinal neoplasm are malnourished and that only one out of five malnourished patients receives some type of preoperative nutritional intervention.15 For this reason, all the scientific organisations connected with enhanced recovery recommend screening and nutritional assessment of all patients who are going to be treated with major surgery and starting nutritional therapy in those who are malnourished.1,2,7,8 On this subject there has been uniform and consistent agreement on the part of the two organisations for all the statements consulted, except in the importance of assessing muscle mass and functional capacity, despite the fact that we have all had a favourable opinion on the use of prehabilitation and adding physical exercise to nutritional therapy. The negative impact of sarcopaenia on postoperative clinical outcomes has been widely demonstrated.16,17 Although there has also been consistency between the two groups of experts regarding the need to start preoperative nutritional therapy in malnourished patients, we have not reached an agreement regarding the degree of malnutrition and the time required for nutritional treatment to obtain postoperative benefits.

Another key point in the immediate preoperative period of the ERAS programmes is in relation to avoiding the midnight fast,18,19 and to the use of carbohydrate drinks as a treatment to improve insulin resistance and patient well-being.20,21 Fortunately, there has also been consistent uniform agreement on these items in considering that the administration of clear liquids and drinks rich in carbohydrates up to two hours before anaesthetic induction is safe and beneficial for the patient. The scarce evidence available on the use of drinks rich in carbohydrates in diabetic patients has meant that we have not reached an agreement on this issue.

It has been widely demonstrated that early initiation of oral feeding in the first hours after surgery is safe22 and is associated with a decrease in postoperative infectious complications and hospital stay without increasing the risk of anastomotic leaks, repositioning of the nasogastric tube or mortality.23,24 Unfortunately, on this key point of the ERAS programme, there has been no consistent agreement by either of the two scientific organisations, although it is surprising that there is a favourable and homogeneous opinion and knowledge about the postoperative clinical benefits of early feeding as is recorded in one of the statements. From our point of view, it seems that although we are aware of the importance of early resumption of feeding after surgery, there is still some root in the traditional surgical practice of late initiation of oral diet based on fear of the appearance of the dreaded anastomotic leaks.

Immunonutrition (IMN) is one of the topics that continues to generate controversy today despite being a strategy to reduce surgical risk that was proposed more than 25 years ago. It seems that this controversy has affected the opinion of our experts from both organisations, since no consistent agreement has been reached on any of the six items related to enteral and parenteral IMN.

Several reviews and meta-analyses, with some limitations and of variable quality, have shown that the use of enteral IMN during the perioperative or postoperative period reduces postoperative infectious complications and hospital stay.25–28 This observed improvement in clinical outcomes is more evident in malnourished neoplastic patients.28 Spanish authors have analysed the use of perioperative IMN in the ERAS context and have demonstrated a reduction in infectious complications.29 Some meta-analyses have suggested that the use of IMN exclusively in the preoperative period does not improve clinical results when compared to a standard nutritional supplement.30 For all these reasons, in the update of the ERAS pathway, it is noted that IMN seems recommendable in malnourished patients treated with gastrointestinal surgery for cancer, but there is not enough evidence to recommend it exclusively in the preoperative period compared to the use of standard oral supplements.12

In the case of parenteral IMN, the latest ERAS guidelines consider the supplementation of parenteral nutrition with glutamine and omega-3 fatty acids in surgical patients, since it has demonstrated its safety and clinical benefits associated with a reduction in infectious complications and hospital stay.7

Despite the fact that the two organisations have reached a consensus on a large number of the nutritional and metabolic strategies for intensified recovery, even today the ERAS pathway is not fully implemented in many Spanish hospitals and the degree of adherence to some of the nutritional care options proposed in this project continues to be low. According to the Power study, a multicentre prospective study, the percentage of compliance in Spanish hospitals with fundamental strategies such as screening and perioperative nutritional treatment, avoiding fasting, treatment with drinks rich in carbohydrates and early postoperative feeding is 67%, 62%, 28% and 35%, respectively.6

In conclusion, this publication represents, to our knowledge, the first consensus document in relation to the nutritional and metabolic measures of ERAS programmes. Although we should congratulate ourselves since the different health professionals involved in the surgical process have managed to reach a consistent agreement on most of the proposed statements, there are still important issues on which we must continue working together to reach a consensus. We believe that this document could become a starting point for trying to homogenise this care, maximise the dissemination of the contents of the new ERAS pathway and help towards uniform implementation in all hospitals in Spain.

FundingThe NutRICA study was financed by Vegenat Healthcare S.L, Badajoz, Spain.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

To all members of the Nutrition Departments of SEEN and GERM who participated in the NutRICA project. To Scientia Salus, for the work as technical secretary.

SEEN Nutrition Department:

M. Victoria García Zafra, Amelia Marí Sanchis, Pablo Suarez Llanos, Diego Bellido Guerrero, Juan Parra Barona, M. Luisa Fernandez Soto, Patricia Díaz Guardiola, Carlos Miguel Peteiro Miranda, Carmen Tenorio Jiménez, Elena Parreño Caparrós, Jose Jorge Ortez Toro, Angela Martin Palmero, Silvia Mauri Roca, Cristina Maldonado Araque, Begoña Molina Baena, Iris Mercedes de Luna Boquera, Samara Palma Milla, M. del Rosario Vallejo Mora, Concepción Vidal Peracho, Araceli Ramos Carrasco, Luisa Muñoz Salvador, Lorena Suárez Gutiérrez, Pilar Matía Martín, María Ballesteros Pomar, Luis Miguel Luengo Pérez, Francisco Botella Romero, Gabriel Olveira Fuster, Ana Zugasti Murillo, Rosa Burgos Pelaez, Emilia Cancer Minchot, Juan José López Gómez, Francisco Villazón González, Rafael López Urdiales, Ángel Luis Abad González, Carmen Aragón Valera, Miguel Civera Andrés, María Lainez López, José Joaquín Alfaro Martínez, Rocío Campos del Portillo, María Riestra Fernández, Elena Carrillo Lozano, Álvaro García-Manzanares Vázquez de Agredos, Carmen Arraiza Irigoyen, Inmaculada Prior Sánchez, Dolores del Olmo Garcia, Carmen Gómez Candela, Jara Altemir Trallero, Natalia Colomo Rodríguez, Francisco Pita Gutierrez, Josefina Olivares, Laura Borau Maorad, Julia Alvarez Hernández, Yaiza García Delgado, Ana Hernández Moreno, M. José Martínez Ramírez, Cristina Campos Martín, Ana Herrero Ruiz, Migueal Ángel Martínez Olmos, Beatriz Lardiés Sánchez, Daniel Antonio de Luis Román, Natalia Ramos Pérez, Carlos Sánchez Juan, Laia Casamitjana Espuña, Ana Agudo Tabuenca, Irene Breton Lesmes, Ana Urioste, Angela González Díaz-Faes, M. Ángeles Vicente Vicente.

GERM:

Marina Varela Duran, Bakarne Ugarte Sierra, Aitor Landaluce, Leyre Gambra, Cristina Ruiz Romero, Pablo Vázquez Barros, Mercedes Estaire Gómez, Alberto Carrillo Acosta, José Miguel Valverde Mantecón, Olga Blasco Delgado, Antonio Arroyo Sebastián, Carlo Brugiotti, Francisco Javier Blanco, Jaime Ruiz-Tovar Polo, Carlos Díaz Lara, José Luis Sánchez Iglesias, Pablo Colsa Gutiérrez, Débora Acín Gándara, Omar Abdel-lah Fernandez, José Antonio Gracia Solanas, Marcos Bruna Esteban, Juan Pablo Marín Calahorrano, Miguel León Arellano, Federico Ochando Cerdan, Javier longás Valién, Alfredo Abad Gurumeta, Ana Soto Sanchez, Tihomir Georgiev Hristov, Ane Abad Motos, Javier Ripollés Melchor, Maria del Carmen Pérez Durán, Elizabeth Redondo, Camilo Castellon Pavon, Alejandro Garcia, Esther Garcia Villabona, Carmen Vallejo Lantero, Raquel Aranzazu Latorre Fragua, Joana Miguel Perelló, Carmen V. Pérez Guarinos, José Andrés García Marín, Victoriano Soria Aledo, José Alberto Pérez García, Ignacio Garutti Martinez, Lluis Cecchini Rosell, Susana Manrique Muñoz, Marga Logroño Ejea, Antonio Servera Ruiz de Velasco, Rajesh-Haresh Gianchandani Moorjani, Luis Sánchez-Guillén, Raquel Sánchez Santos, Enrique Moncada Iribarren, José López Fernández, Alfredo Manuel Estévez Diz, Izaskun Balciscueta Coltell, Cristina Roque Castellano, Jose Manuel Gutierrez Cabezas, Jose Ramon Rodríguez Fraile, Silvia Castellarnau Uriz, Pilar Sierra, Eva Maria Nogues Ramia, Ana Pascual Pedreño, Eugenia Peiró González, Mónica Reig Pérez, Beatriz Cros Montalbán, José Fernando Trebollé, Pilar Palacios, Mónica Valero Sabater, Pedro Antonio Pacheco Martínez, Luis Miguel Jiménez Gómez, Paula Dujovne Lindenbaum, Macarena Barbero Mielgo, Belén San Antonio San Roman, Viktoria Molnar, Isabel Alonso, Matias Cea Soriano, Javier Martinez Ubieto, Ana Pascual Bellosta, Sonia Ortega Lucea, Berta Perez, Lucía Tardós Ascaso, Idelia Mateu Guillamon, Silvia Llopis Pla, María Aymerich de Franceschi, Maria del Campo Lavilla, Luis Antonio Fernández Fernández, Jose Miguel Lozano Enguita, Enrique Alday Muñoz, Roger Cabezali Sánchez.

The names of the components of the NutRICA working group of the Nutrition Departments of SEEN and GERM are given in Appendix A.

Please cite this article as: Ocón Bretón MJ, Tapia Guerrero MJ, Ramírez Rodriguez JM, Peteiro Miranda C, Ballesteros Pomar MD, Botella Romero F, et al. Consenso multidisciplinar sobre la terapia nutricional y metabólica en los programas de recuperación intensificada en cirugía abdominal: Proyecto NutRICA. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2022;69:98–111.