Hyperglycemia is a common finding at hospital emergency rooms in diabetic patients, but few data are available on its frequency, management, and subsequent impact based on the assessment made at emergency rooms.

ObjectivesTo ascertain the frequency of diabetes mellitus and hyperglycemia in patients admitted from emergency rooms. Second, to describe management of hyperglycemia at emergency rooms, and to analyze its potential impact on the course and management of patients during admission.

Patients and methodsAll patients admitted from the emergency room for three consecutive weeks were enrolled. Hyperglycemia was defined as two blood glucose measurements ≥180mg/dL in the first 48h after admission.

Results36.6% of patients admitted from the emergency room were diabetic, and 58% of these had early, sustained hyperglycemia. On the other hand, 27% of patients admitted from the emergency room had hyperglycemia (78.3% of diabetic patients and 21.7% with no known diabetes). Diabetic patients with hyperglycemia had higher blood glucose levels than non-diabetic patients (p<0.01). Average hospital stay was 8±6.4 days, with no differences between the groups. Hyperglycemia is rarely reported as a diagnosis in the emergency rooms discharge report. In standard hospitalization, this diagnosis appears more commonly in patients with known diabetes (OR 2.5; p<0.001).

ConclusionsPrevalence of diabetic patients admitted from emergency rooms is very high. In addition, although hyperglycemia is very common in patients admitted from emergency rooms, there is a trend to underestimate its significance. Based on our results, we think that implementation of measures to give greater visibility to diagnosis of hyperglycemia could help improve application of established protocols.

La hiperglucemia es un hallazgo habitual en los Servicios de Urgencias Hospitalarios así como la atención de pacientes diabéticos, pero existen pocos datos sobre su frecuencia, manejo y repercusión posterior en función de la valoración que se le haya dado en dichos servicios.

ObjetivosDeterminar la frecuencia de diabetes mellitus y de hiperglucemia en los pacientes que ingresan desde Urgencias. En segundo lugar, describir el manejo en Urgencias de la hiperglucemia, y analizar la influencia que pudiera tener en la evolución y en el manejo del paciente durante su ingreso.

Pacientes y métodosDurante 3 semanas consecutivas se incluyeron todos los pacientes ingresados desde el Servicio de Urgencias del Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa. La hiperglucemia se definió como 2 determinaciones de glucosa ≥ 180mg/dl, separadas al menos 8 h y en las primeras 48 h de estancia hospitalaria.

ResultadosEl 36,6% de los pacientes que ingresaron desde el Servicio de Urgencias eran diabéticos, y de ellos el 58% presentaban hiperglucemia precoz y mantenida. Por otro lado, el 27% de los pacientes que ingresaban desde urgencias presentaban hiperglucemia (78,3% de pacientes diabéticos y 21,7% sin diabetes conocida). La hiperglucemia de los pacientes que ya eran diabéticos era significativamente más intensa que la hiperglucemia de los no diabéticos conocidos (p<0,01). La estancia media en planta fue de 8±6,4 días, sin que se observaran diferencias entre los distintos grupos. En urgencias no se solía mencionar la hiperglucemia dentro de la lista de diagnósticos mientras que en el informe de alta desde planta existía mayor probabilidad de que se hiciera referencia a la hiperglucemia en los pacientes con diabetes previa que en las nuevas hiperglucemias (p<0,001, OR 2,5).

ConclusionesLa prevalencia de pacientes diabéticos que ingresan desde Urgencias es muy alta. Además, a pesar de que la hiperglucemia es muy frecuente en los pacientes que ingresan desde el Servicio de Urgencias, se tiende a subestimar su importancia. En base a nuestros resultados, creemos que la implantación de medidas que ayuden a aportar mayor visibilidad al diagnóstico de hiperglucemia podrían ayudar en la mejora de la aplicación de los protocolos establecidos desde los Servicios de Urgencias Hospitalarios.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a highly prevalent chronic disease that has high social costs and a great impact on healthcare due to the development of acute and chronic complications that decrease patient quality of life and life expectancy. The prevalence of DM in Spain is 13.8%, and approximately half of those affected (6%) are unaware of their disease. Prevalence increases with age, and is higher in men than in women.1

The prevalence of DM among patients admitted to hospital ranges from 20% to 40% depending on the series, and the prevalence of hyperglycemia among those admitted is even higher.2–7 However, few data are available in Spain on the frequency of diabetes and/or hyperglycemia found at hospital emergency rooms (ERs). Hyperglycemia at ERs is important because it is a metabolic complication often associated with a poorer course and longer hospital stay, especially among patients not previously known to have diabetes. This has been related to a lesser prescription of insulin for those patients.2,8–15 Although there are many possible reasons why this metabolic disorder may have a harmful effect on the course of the acute conditions that cause patients to seek care,16,17 there is still controversy as to whether hyperglycemia occurs as the result of a poor prognosis, or whether it is only a marker of a more severe disease. On the other hand, blood glucose control at hospitals is far from optimal.18–20

The objective of this study was to analyze the frequency of DM and hyperglycemia in patients admitted from ERs, and to learn how both patients with known diabetes and with new-onset hyperglycemia were managed at ERs and hospital wards, in order to find possible areas for improvement. This study also aimed to assess whether hyperglycemia was included in the list of diagnoses at admission from the ER and the potential impact of such an inclusion.

Patients and methodsStudy scope and populationHospital Universitario Severo Ochoa in Leganés (Madrid) is an area hospital for the Community of Madrid that in 2015 received 110,808 emergency visits, of which 71,766 were seen at the general emergency room (11,564 at the gynecology and obstetric ER, and 27,478 at the pediatric ER).

Study designA prospective, observational study was conducted of all patients aged 18 years or older admitted from the general ER of Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa over a period of three consecutive weeks between January and February 2015.

In case of repeat visits, only the first visit was taken into consideration. Pregnant women and patients who did not give their consent were not included.

Definitions and classification of study groupsHyperglycemia was defined using a cut-off point of 180mg/dL, based on the American Diabetes Association's published recommendations6 on target values for inpatients.

A prior history of diabetes was considered to exist if so reported by the patient, if recorded in prior medical records, or if the patient had been prescribed antidiabetic drug treatment for home administration.

The patients enrolled were monitored during the first 48h of their hospital stay and were divided into four groups based on the two highest blood glucose levels found in tests requested by their physician. The groups were defined as follows:

- a)

Normoglycemia: patients with blood glucose levels within normal limits (70–180mg/dL) or a single measurement ≥180mg/dL and one normal measurement.

- b)

Hyperglycemia with previously known diabetes: patients with a known history of DM and two glucose measurements ≥180mg/dL.

- c)

New-onset hyperglycemia: patients with no previous history of DM and two glucose measurements ≥180mg/dL.

- d)

Not analyzable patients, defined as those who met at least one of the following exclusion criteria:

- -

Patients discharged before 48h had elapsed, or who, after initial assessment at the general ER, were transferred to departments other than the so-called “medical departments” such as surgery, orthopedic surgery, gynecology, urology, otorhinolaryngology, or psychiatry.

- -

Patients for whom two separate capillary or plasma glucose measurements were not ordered with an interval of more than 8h.

- -

Patients with an episode of hypoglycemia during their hospital stay (defined as a glucose level less than 70mg/dL).

- -

At the same time, patients in the hyperglycemia groups were divided into two subgroups depending on whether they had moderate hyperglycemia, defined as the presence of one of the two selected measurements <250mg/dL, or severe hyperglycemia when both measurements were ≥250mg/dL.

Data collectionIn this observational study, data were prospectively collected on the clinical characteristics, glucose measurements, course, and treatment of patients admitted from the ER.

Demographic, anthropometric, laboratory, and clinical variables were collected at two timepoints: by a survey within 48h of admission to the ER, and by reviewing the clinical history and discharge report after patient discharge from the ward.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa. All patients analyzed signed an informed consent before enrolment.

Data analysisSample sizeThis was a descriptive study of the frequency of DM in the population who attended the ER and was subsequently admitted to a hospital ward. As this was not a hypothesis-testing study, a representative sample of the study population was used to describe the demographic and clinical characteristics. Approximately 10 patients were admitted from the ER daily, that is, 300 every month. Approximately 1/3 of that population (110) was considered a clinically significant sample for conducting a descriptive study of patient characteristics. Statistically, this sample allowed us to identify in a significant manner variables occurring with a frequency of 10%, with an accuracy of 5% and a 95% confidence level. It also allowed us to calculate the mean value of quantitative variables with a variance up to S2=250 at the same confidence level.

Statistical analysisQualitative variables are presented with their frequency distributions. Quantitative variables are summarized by mean and standard deviation, or median and interquartile range.

Clinical characteristics were compared in patient subgroups by category to assess their differences; for two-category variables, a Student's t test for independent samples in quantitative variables was used; an analysis of variance was used if more than two categories were assessed. Results are given as difference in means and proportions with their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). For qualitative variables, a chi-square test was used, or a Fisher's exact test if more than 25% of the expected were fewer than 5.

In all hypothesis tests, the null hypothesis was rejected with a type I error or an α error less than 0.05.

SPSS for Windows version 15.0 was the statistical package used for analysis.

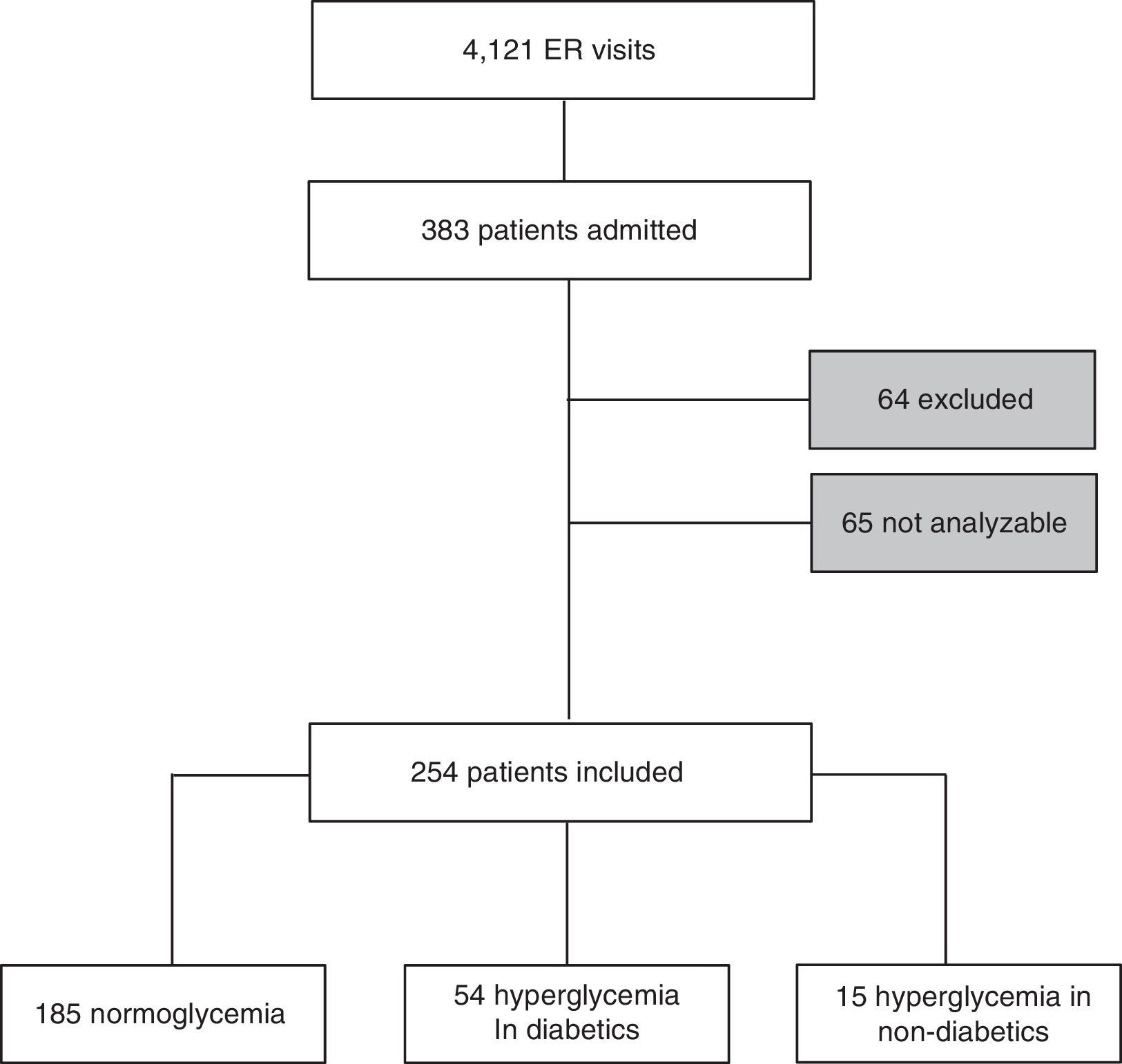

ResultsDuring the three weeks of the study, 6500 patients attended the ER of Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa. Of these, 4121 were seen at the general ER, 697 at the gynecology and obstetrics ER, and 1682 at the pediatrics ER. A total of 383 patients were admitted from the general ER to one of the so-called “medical departments” of the hospital. Sixty-four patients were excluded from the study because they did not sign the informed consent, and another 65 patients were not analyzable. Thus, the study was conducted on 254 patients who met all the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The main reasons preventing analysis of these patients were the absence of at least two glucose measurements (56.9%), followed by discharge before 48h (26.1%), hypoglycemia (12.3%), and admission before 48h of stay at the ER (4.6%).

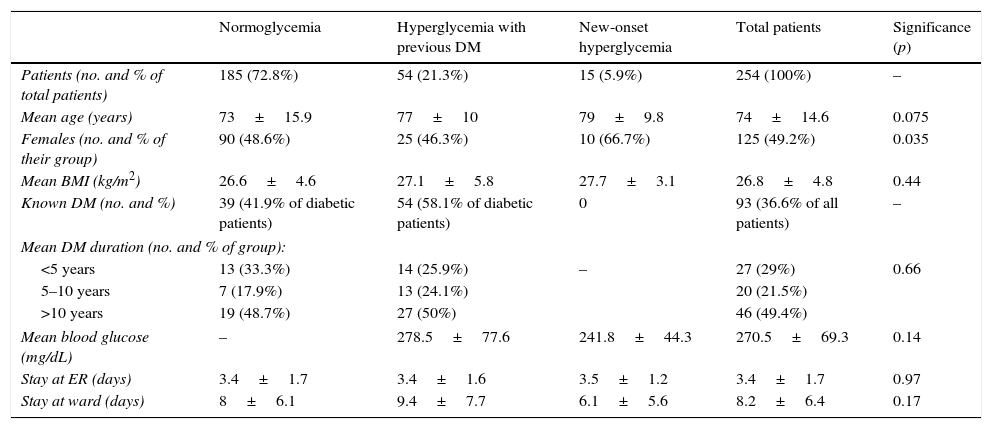

Table 1 shows patient characteristics. There were no statistically significant differences between the three groups in terms of sex, age, body mass index, or stay at the ER or wards. The diagnosis leading to the admission of the patients analyzed was independent of their group.

Patient characteristics.

| Normoglycemia | Hyperglycemia with previous DM | New-onset hyperglycemia | Total patients | Significance (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (no. and % of total patients) | 185 (72.8%) | 54 (21.3%) | 15 (5.9%) | 254 (100%) | – |

| Mean age (years) | 73±15.9 | 77±10 | 79±9.8 | 74±14.6 | 0.075 |

| Females (no. and % of their group) | 90 (48.6%) | 25 (46.3%) | 10 (66.7%) | 125 (49.2%) | 0.035 |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) | 26.6±4.6 | 27.1±5.8 | 27.7±3.1 | 26.8±4.8 | 0.44 |

| Known DM (no. and %) | 39 (41.9% of diabetic patients) | 54 (58.1% of diabetic patients) | 0 | 93 (36.6% of all patients) | – |

| Mean DM duration (no. and % of group): | |||||

| <5 years | 13 (33.3%) | 14 (25.9%) | – | 27 (29%) | 0.66 |

| 5–10 years | 7 (17.9%) | 13 (24.1%) | 20 (21.5%) | ||

| >10 years | 19 (48.7%) | 27 (50%) | 46 (49.4%) | ||

| Mean blood glucose (mg/dL) | – | 278.5±77.6 | 241.8±44.3 | 270.5±69.3 | 0.14 |

| Stay at ER (days) | 3.4±1.7 | 3.4±1.6 | 3.5±1.2 | 3.4±1.7 | 0.97 |

| Stay at ward (days) | 8±6.1 | 9.4±7.7 | 6.1±5.6 | 8.2±6.4 | 0.17 |

Of the 254 patients, 185 were in the normoglycemia group (72.8%), 54 in the hyperglycemia in a known diabetic group (21.2%), and 15 in the new-onset hyperglycemia group (5.9%); that is, 27% of patients admitted from the ER had blood glucose levels above 180mg/dL at least twice in the first 48h after admission.

Of the patients admitted from the ER, 36.6% were diabetic, and 58% of these had sustained hyperglycemia, at least at the start of admission. DM had started more than 10 years before in almost half the patients (49.4%).

Hyperglycemia was moderate in 65.2% of cases, and most of the more severe hyperglycemic episodes occurred in patients with known diabetes (23 of the 24 most severe hyperglycemic episodes) (p<0.01).

The mean ER stay was 3.4±1.7 days, with no differences between the groups. The mean stay at the ward was 8.2±6.4 days, with no differences either between the groups.

Most patients with hyperglycemia received some treatment at the ER (89.9%), regardless of the severity of hyperglycemia (p=0.22). It should be noted that each patient could receive several treatment modalities at the ER: 80.6% were prescribed diet for DM, 72.6% a corrective regimen, 48.4% scheduled long-acting insulin, and 53.2% scheduled rapid-acting insulin.

During the ward stay, the treatment modalities used were: diet for DM in 87.3% of cases, corrective regimen in 58.7%, scheduled long-acting insulin in 66.7%, and scheduled rapid-acting insulin in 81% of cases.

Glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was not tested in 53.7% of the diabetics admitted with hyperglycemia, and more than half of these (55.1%) also had had no HbA1c level recorded in the previous three months. In the group with new-onset hyperglycemia, HbA1c was requested for 60% of the patients during their hospital stay. The severity of hyperglycemia was not a determining factor for requesting the test. Mean HbA1c values at the ER were 8.1±1.6% in patients with severe hyperglycemia and 7.7±2.4% in patients with moderate hyperglycemia, with no statistically significant differences (p=0.61).

Hyperglycemia was not usually included at ERs in the list of diagnoses for both known diabetic and non-diabetic patients (it was listed in 7.5% and 13.4% respectively). Hyperglycemia appeared more frequently in the discharge report from the ER (it was reported in 72.3% of diabetics and in 26.7% of non-diabetics), and in fact it was more likely to be reported for diabetics than for cases of new-onset hyperglycemia (p<0.001; OR 2.5).

In addition, in severe hyperglycemia, the discharge report was more likely to include the diagnosis (p=0.09) and to recommend some indication or treatment modification (p=0.11).

DiscussionSample characteristicsThis is the first study in Spain to count how many diabetic patients are admitted from the ER and the early and sustained hyperglycemia that may already be detected at the start of admission both in known diabetics and in non-diabetics. The admission rate of diabetics from ERs was higher in our study than in other series of patients already hospitalized,2 and half the patients had long-standing diabetes. It should be noted that patients who attend the ER usually have other cardiovascular risk factors and a high overall cardiovascular risk.21 These cardiovascular risk factors, including metabolic decompensations, and their potential complications should, therefore, be taken into consideration.

The usual standardized definitions of hyperglycemia are not very useful in the setting of ERs. Thus, it seemed more appropriate to use the postprandial value recommended by the American Diabetes Association during hospitalization,6 because patients managed in this context are not usually fasting, and present circumstances that may favor an increase in blood glucose levels. Additionally, and to reduce the results attributable to isolated, transient, and sporadic stress hyperglycemia detected at the ER, we added the condition that the result had to be obtained at least twice before being considered hyperglycemia. Compared to other studies, we used a very strict definition of hyperglycemia,2,4 and the results may therefore be even more valuable. In our study, early and sustained hyperglycemia occurred in more than one out of every four patients admitted from the ER. On the other hand, the size of our sample and the limited number of patients considered “cases” based on such a strict definition may have prevented some results from achieving statistical significance.

Other studies, such as the one conducted by Umpierrez in inpatients, or the GLUCEMERGE study conducted at the ER,2,3 found hyperglycemia rates similar to the one reported here, despite the fact that the prevalence of DM was higher in our study. This may be related to the higher cut-off point used to define hyperglycemia in our study. This may also be the reason why we detected fewer cases of new-onset hyperglycemias. As it happens, the percentage of new-onset hyperglycemias found at the ER coincides with the percentage of blood glucose disorders unknown to patients reported by Soriguer in his study of the prevalence of DM in Spain.1 ERs could take advantage of this opportunity to detect hyperglycemia and DM in patients who would otherwise not attend other care facilities that may be better suited for this type of strategy. The early detection of blood glucose disorders may prevent subsequent target organ lesions, and ERs have the capacity to make improvements in this area. Along these lines, mention should be made of the low number of HbA1c requests during the hospital stay, despite the detection of hyperglycemia, in both known diabetics and in patients with new-onset hyperglycemia, whom the test would also help to differentiate from patients with stress hyperglycemia, and which would facilitate subsequent outpatient care for all patients.

As in the series mentioned above, and despite different cut-off points, hyperglycemia in our diabetics was more severe than in patients without previously known diabetes, and most diabetics had early and sustained hyperglycemia when they are admitted from the ER.

Hospital stayHyperglycemia is associated with longer stays, more complications (including ICU stay), and greater mortality.3 Our study found no statistically significant differences in mean stay, but stays tended to be longer in diabetics with hyperglycemia than in those with normoglycemia or new-onset hyperglycemia. These data differ from those reported in other studies, such as the one by Umpierrez,2 which found longer stays for patients with new-onset hyperglycemia and with hyperglycemia (diabetic and non-diabetic) as compared to normoglycemic patients.

These discrepancies could be due to sample size, but logically they were also affected by the hyperglycemia cut-off point at 180mg/dL, the condition that this should be found twice, and the fact that the mean age of our patients was almost 20 years older than in the Umpierrez study. However, studies with greater statistical power that could confirm these results in older populations such as ours are required.

Degree of controlVerification of the degree of control over the previous few months in patients admitted with hyperglycemia and the measurement of HbA1 care is clearly areas where there is room for improvement both at ERs and conventional hospital facilities. This does not apply to our hospital alone. According to other related articles,2 one limitation is the inability to determine whether hyperglycemia is an acute or a long term condition.

On the other hand, more severe hyperglycemias detected within 48h of admission are usually associated with higher HbA1c levels. This may be of help when deciding on changes in hypoglycemic treatment after admission from the ER, where HbA1c levels cannot be requested, but does not justify the absence of this laboratory value.

Diagnosis and recommendationsAlthough the vast majority of patients are treated for hyperglycemia during their stay at ERs, this diagnosis is reported in only a minority of cases. In fact, mention of this diagnosis is likely to be absent in the reports of patients who were not known diabetics, both at the ER and the ward, despite the fact that these patients tend to have a poorer prognosis.2

This diagnosis appears in a higher proportion of ward discharge reports as compared to the ER, but is more commonly recorded for patients with more decompensated blood glucose levels. In these cases, some change in treatment is also more usually recommended. The GLUCEMERGE study3 also underscores this fact at ER level, reporting a trend to underestimate the importance of recording hyperglycemia and appropriate recommendations for its management. Mentioning the diagnosis of hyperglycemia in the report may facilitate subsequent management of the patient.

TreatmentNumerous studies have clearly shown that control of hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients is far from optimal.20,22,23 Protocols recommend that diabetic patients are treated with scheduled basal-bolus insulin regimens during their hospital stay, but at ERs this treatment is prescribed to less than half the patients, despite their poor glucose control at admission. This represents an obvious area for improvement. The proportion of patients given this treatment increases in the ward, but is still far from optimal. Practitioners tend to underestimate hyperglycemia and relegate it to the background. It is possible that hypoglycemia has been correctly assumed to be counterproductive but, by extension, that hyperglycemia has also been assumed to be more tolerable, sometimes ignoring the literature on the subject, when what should be achieved is a reasonable balance that avoids hyperglycemia without risking hypoglycemia. Excessive permissiveness with regard to hyperglycemia is probably also linked to practitioners feeling uncomfortable with the diversity of hypoglycemic treatments, which leads to abuse even of sliding scale insulin regimens, which can be ineffective and counterproductive if used instead of scheduled insulin regimens; added to this is the absence of treatment adjustment despite poor blood glucose control.22–24 A better compliance with the established protocols is desirable.

As in other series, there seems to be a trend to maintain treatment25: in almost half the patients, treatment was not modified despite “poor control”. This is an example of so-called clinical inertia, both at diagnosis and treatment, which leads to the decision of the first physician who diagnoses and prescribes treatment rarely being changed at a later date despite poor glucose control during admission.25 A patient admitted to hospital or attending the ER for any reason should not be discharged without assessment of his or her metabolic control, because intensification of treatment, when indicated, decreases the chance of readmission.26

ConclusionsDM is a very common cardiovascular risk factor in patients seen at ERs. In addition, there is a high proportion of patients admitted from ERs with early and sustained hyperglycemia, even among patients without known DM. For this reason, ERs should be involved in the implementation of any protocol for the management or improvement of care for diabetic patients.

The importance of hyperglycemia tends to be underestimated, and improvements are needed as regards both HbA1c measurement in admitted patients and treatment modification when required. Hospital and ER admission is currently not being used to fulfill this function, which would save time and unnecessary consultations at other healthcare levels.

On the other hand, the absence of HbA1c data does not exempt emergency physicians from modifying treatments, at least in patients with higher blood glucose levels. Such treatments should follow more closely the current recommendations for patients, both those seen at the ER and those admitted to hospital wards, as well as the directives to maintain adequate control after discharge. We should not forget that the disease is the patient's constant companion, even when the patient ceases to be under our care at the hospital.

It is desirable, too, that hyperglycemia be recorded in reports as one more sufficiently important condition with the capability to affect the course of the patient's disease. We think that the implementation of measures that help make the diagnosis of hyperglycemia more visible could also help improve the application of protocols established at ERs.

Authors contributionAll the authors have collaborated in the development of all the sections of the document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Álvarez-Rodríguez E, Laguna Morales I, Rosende Tuya A, Tapia Santamaría R, Martín Martínez A, López Riquelme P, et al. Frecuencia y manejo de diabetes mellitus y de hiperglucemia en urgencias: Estudio GLUCE-URG. 2017;64:67–74.